Commission To Investigate Allegations Of Police Corruption And The Anti-Corruption Procedures Of The New York City Police Department

Interim Report And Principal Recommendations

Milton Mollen, Chair

Harold Baer, Jr.

Herbert Evans

Roderick C. Lankier

Harold Tyler

Joseph P. Armao, Chief Counsel

Leslie U. Cornfeld, Deputy Chief Counsel

December 27, 1993

INTERIM REPORT AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Table of Contents:

• Preface

• I. The State of Police Corruption

o The Nature and Extent of Police Corruption: An Overview

o Police Culture

o Forms of Corruption

Narcotics-Related Corruption

Police Violence

Perjury, False Statements and Records

• II. The Failures of the Department's Corruption Controls

o The Department Abandoned Its Responsibility to Ensure Integrity

o The Department Failed to Address Aspects of Police Culture That Foster Corruption

o The Department Had a Fragmented Approach to Corruption Control

o The System of "Command Accountability" Collapsed

o The Department Allowed the FIAUs to Collapse

o The Internal Affairs Division Abandoned Its Mission

o The Department Used a Badly Flawed Investigative Approach for Police Corruption

o Corruption Cases Were Concealed

o The Department's Intelligence Gathering Efforts Were Flawed

o Supervision Was Diluted and Ineffective

o Recruit and In-Service Integrity Training Was Neglected

o Effective Deterrence Was Absent

o Drug and Alcohol Abuse Policies Were Ineffective

• III. Principal Recommendations

o The External Monitor

• Conclusion

INTERIM REPORT AND PRINCIPAL RECOMMENDATIONS

Preface

For the past century, police corruption inquiries into the New York City Police Department have run in twenty-year cycles of scandal, reform, backslide, and fresh scandal. The creation of this Commission followed the same historical pattern.

In May 1992, six New York City police officers assigned to two different Brooklyn precincts were arrested not by the New York City Police Department's Internal Affairs Division ("IAD"), but by Suffolk County Police. The officers were charged with narcotics crimes that arose from their association with a drug ring in Suffolk County.

Shortly thereafter, the press disclosed that one of the arrested officers, Michael Dowd, had been the subject of fifteen corruption allegations received by the New York City Police Department over a period spanning six years -- and that not a single allegation ever had been proven by the Department, despite substantial evidence that Dowd regularly and openly engaged in serious criminal conduct. Questions arose as to whether Dowd was an aberration or whether corruption had once again become a serious problem within the Department, and whether the Department was able and willing to police itself.

In July 1992, Mayor David N. Dinkins responded by establishing this Commission and assigning it three tasks of deep public concern: to investigate the nature and extent of corruption in the Department; to evaluate the Department's procedures for preventing and detecting corruption; and to recommend changes and improvements in those procedures.

In September 1992, with a twenty-person staff of attorneys and investigators, the Commission began its work. We embarked upon a wide-ranging investigation to determine whether the corruption of Michael Dowd and the Department's failure to apprehend him illustrated deeper problems about police corruption and culture, and about the Department's competence and commitment to control corruption.

To carry out our mandate, the Commission sought information from a wide variety of sources. We reviewed thousands of Department documents and case files; conducted hundreds of private hearings and interviews of former and current police officers of all ranks; audited, investigated, and conducted performance tests of the principal components of the Department's anti-corruption systems; analyzed hundreds of investigative and personnel files; interviewed private citizens, alleged victims of corruption, and criminal informants; conducted an extensive literature review on police corruption and prevention; and held a series of roundtable discussions and other meetings with a variety of police management and corruption experts including local, state and federal law enforcement officials, prosecutors, former and current police chiefs and commissioners, inspectors general, academics, and police union officials.

The Commission also initiated a number of its own field investigations, sometimes in conjunction with local and federal prosecutors, targeting areas where our analysis suggested police corruption existed.

The Commission received invaluable assistance from numerous police officers and supervisors who agreed to act as confidential sources of information about the state of the Department's corruption controls and investigations, including IAD investigators and supervisors, and undercover and field associate officers. Nine corrupt officers, including Michael Dowd, provided the Commission with detailed information about their own and other officers' corrupt activities. A number of honest officers also provided information about corruption in their commands.

Throughout our work, we benefitted from the counsel of many people, including Mark H. Moore and David M. Kennedy of Harvard University's John F. Kennedy School of Government, and Special Counsel Jonny J. Frank.

During the course of its investigation, the Commission developed extensive evidence about the state of police corruption in our City, the state of the Department's corruption-controls, and the Department's ability and willingness to control corruption. From September 27 through October 7, 1993, the Commission held two weeks of public hearings to present much of the information we had uncovered in the primary areas of our mandate.

***

From the beginning of our investigation, we were struck by the difference between what the Commission was uncovering about the state of corruption and corruption controls within the Department, and what the Department was publicly -- and privately -- stating about itself. The Department maintained that police corruption was not a serious problem, and consisted primarily of sporadic, isolated incidents. It also insisted that the shortcomings that had been disclosed about the Department's anti-corruption efforts reflected, at worst, insufficient resources and uncoordinated organization of internal investigations.

The Commission found that the corruption problems facing the Department are far more serious than top commanders in the Department would admit. We determined that police corruption and brutality are serious problems, and that narcotics-related corruption occurs, in varying degrees, in many high-crime, narcotics-ridden precincts in our City. We also found an anti-corruption apparatus that was totally ineffective and -- worse -- a Department that was unable and unwilling to acknowledge and uncover the scope of police corruption. As a result, the Department's anti-corruption efforts were more committed to avoiding disclosure of corruption than to preventing, detecting and uprooting it.

This institutional reluctance to acknowledge and uncover corruption is not surprising. Few organizations act otherwise. Police organizations in particular find it difficult to maintain an effective fight against corruption. It is unrealistic to expect the Department to exert a serious, effective, and sustained anti-corruption effort without outside help and oversight.

The very history of the Department lends weight to this conclusion. Despite cycles of scandal and reform spanning over a century, none has led to effective long-term remedies. The Commission is neither so naive nor optimistic to suggest that any reforms could ever entirely eliminate police corruption -- or corruption in any profession. But we are convinced that there are reforms that can permanently strengthen the Department's corruption controls, and that can help break the twenty-year cycles of scandal and reform to which the Department has been captive.

One such critical reform, which is the principal recommendation addressed in this report, is the creation of a permanent outside agency to monitor and improve the Department's capacity for preventing and pursuing corruption, and to ensure the Mayor, Police Commissioner, and the public that the Department's anti-corruption efforts do not again erode with time. Enhancing the Department's internal efforts to prevent and uncover corruption, of course, is also critical, and we will make recommendations as to how this can be done in our final report.

What follows is an interim report summarizing the Commission's findings and recommendations for external oversight. The Commission's basic findings have become sufficiently clear, its principal recommendations sufficiently well developed, and the situation in the Department and the City sufficiently serious that the Commission feels called upon to issue an interim report at this time. Detailed findings and recommendations, including evidence generated by the Commission's pending investigations, will be presented in our final report, which will be released in the coming months.

I. THE STATE OF POLICE CORRUPTION

The Nature and Extent of Police Corruption: An Overview

The corruption of Michael Dowd was not isolated or aberrational, but represents a new and serious form of corruption that exists in a number of precincts throughout our City. While the systemic and institutionalized bribery schemes that plagued the Department a generation ago no longer exist, the prevalent forms of police corruption today exhibit an even more invidious and violent character: police officers assisting and profiting from drug traffickers, committing larceny, burglary, and robbery, conducting warrantless searches and seizures, committing perjury and falsifying statements, and brutally assaulting citizens. [1] This corruption is characterized by abuse and extortion, rather than by accommodation -- principally through bribery -- typical of traditional police corruption.

Simply put, twenty years ago police officers took bribes to accommodate criminals -- primarily bookmakers; today's corrupt cop often is the criminal. Because of its aggressive and extortionate character, this form of corruption is particularly destructive to relations between the police and the public -- which is especially troubling as the Department expands the practice of community policing.

The vast majority of police officers throughout our City do not engage in corruption. They are honest, hard-working men and women who perform difficult and dangerous duties each day with efficiency and integrity, doing their best to protect the people of our City. The horror many officers expressed at the revelations of the Commission's hearings was heartfelt and sincere.

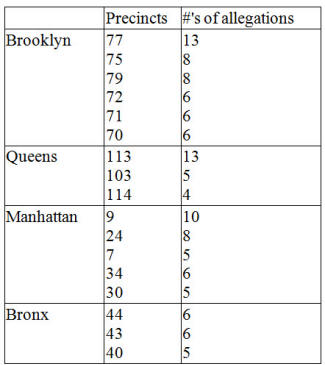

Nonetheless, the Commission determined that corruption, particularly narcotics-related corruption, exists in varying degrees in many high-crime, drug-infested precincts in the City. This is based on the consistent and repeated results of the Commission's investigations; on information from sources within and without the Department; and on our analysis of patterns of corruption complaints. This corruption is not limited to the isolated acts of a few rogue cops, as some have maintained. It is typically committed by groups of police officers assigned to the same command who commit crimes under color of law; through the abuse, and with the protection of their police powers; and often in the shelter of their fellow officers' silence.

Nor is corruption limited to spontaneous crimes of opportunity, as many believe. Corrupt officers create their own opportunities for corruption. They aggressively seek out sources of money, drugs and guns, and often employ sophisticated and organized methods to carry out their criminal activities.

The Commission also found that the most serious and abusive corruption is endemic to crime-ridden, narcotics-infested precincts with predominantly minority populations. These communities are thus doubly victimized: by active trafficking in drugs and guns by the police themselves; and by being denied the police protection and service they so badly need.

Victims of police corruption are often reluctant to complain to the Department, which makes it difficult to uncover, investigate and determine the extent of corruption. This difficulty is augmented by other factors which make police corruption particularly difficult to uncover and investigate, including corruption's often covert and sophisticated nature, and the close ties of loyalty among the officers who perpetrate or witness it.

The Commission found no evidence that this corruption reached high into the Department, or that supervisors were actively and directly involved. Some supervisors do, however, appear to condone perjury, falsification of police records, and acts of brutality. They also facilitate corruption by often closing their eyes to corruption in their commands. Some supervisors knew or should have known about corruption and failed to take the actions necessary to stop it. But even supervisors committed to fighting corruption could not always do so. The Department failed to give supervisors the tools or incentives required to fight corruption effectively, and supervision was notably sparse and ineffective in most precincts where corruption flourished.

Finally, the traditional idea that police corruption is primarily about illicit profit no longer fully reflects what the Commission found on the streets of New York. While greed is still the primary cause of corruption, a complex array of other motivations also spurs corrupt officers: to exercise power; to experience thrills; to vent frustration and hostility; to administer street justice; and to win acceptance from fellow officers. Officers stole guns and drugs not only for profit, but in some instances to show their power, express their frustrations and impose their brand of justice. Officers sometimes used force for legitimate self-defense reasons, but also to steal money or drugs, to teach a lesson that officers believed the courts would not provide, or simply for power and thrills.

What follows is a summary of police attitudes that foster and conceal corruption, and some of the most salient forms of corruption observed by the Commission.

Police Culture

The values and attitudes of police officers enormously influence the presence or absence of corruption and the ability to combat it. Certain tendencies promote corruption, or a tolerance for it. An intense group loyalty, fostered by pride, shared experiences, and a pervasive belief that police can rely only on other police in times of emergency, binds officers together. While loyalty and mutual trust are necessary and honorable aspects of police work, they can generate what is perhaps the greatest barrier to effective corruption control: the code of silence, the unwritten rule that an officer never gives incriminating information against a fellow officer.

The code of silence influences a vast number of police officers, even those who are otherwise honest. Officers who violate the code of silence often face severe consequences. They are ostracized and harassed; become targets of complaints and even physical threats; and fear that they will be left on their own when they most need help on the street. Consequently, many honest officers take no action to stop the wrongdoing they know or suspect is taking place around them. The code of silence also often extends to supervisors, who seek to protect their subordinates from charges of misconduct and their own careers from the taint of scandal.

Another aspect of police culture is the "Us versus them" mentality that many police display, and which is at its worst, in high-crime, predominantly minority precincts. This divisiveness makes many police officers feel isolated from, and often hostile toward, the community they are meant to serve. The Commission's inquiries show that this attitude starts as early as the police academy, where impressionable recruits learn from veteran police officers that the ordinary citizen fails to appreciate the police, and that their safety depends solely on fellow officers. This attitude is powerfully reinforced on the job. It creates strong pressures on police officers to ally themselves with fellow officers, even corrupt ones, and to disregard the interest they have in supportive, productive relationships with the communities and residents they serve.

Police unions and fraternal organizations can do much to change the attitudes of their members. Because of this, we were particularly disappointed when the Patrolmen's Benevolent Association ("P.B.A") declined our invitation to discuss this matter. Moreover, a variety of sources, including police officers and prosecutors, have reported that police unions help perpetuate the characteristics of police culture that foster corruption. In particular, the Commission learned that delegates of the P.B.A. have attempted to thwart law enforcement efforts into police corruption. Rather than acting to protect the legitimate interests of the vast majority of its honest members, the P.B.A. often acts as a shelter for officers who commit acts of misconduct.

The code of silence and the "us versus them" mentality were present wherever we found corruption. These characteristics of police culture largely explain how groups of corrupt officers, sometimes comprising almost an entire squad, can openly engage in corruption for long periods of time with impunity. Any successful system for corruption control must redirect police culture against protecting and perpetuating police corruption. It must create a culture that demands integrity and works to ensure it. The Commission believes such change is possible.

History proves that our optimism is warranted. In response to the Knapp Commission's revelations of systemic corruption and corruption tolerance, then-Commissioner Patrick V. Murphy made significant strides in transforming a culture that committed and tolerated corruption, into one that largely discouraged it. Then, as now, the Department could be divided into three camps: a few determined offenders, a few determined incorruptibles, and a large group in the middle who could be tilted either way, and who are, at the moment, tilted toward corruption tolerance. As it did twenty years ago, the Department must take a variety of steps to reverse this inclination by: emphasizing and spreading the system of "command accountability" and incentives for preventing corruption; strengthening the corruption prevention and investigations apparatus; and inculcating an ideology of pride and integrity throughout the Department.

Any successful plan for reform has to rely heavily on steps to create a culture that discourages corruption. If the culture of the Department tolerates corruption, or conceals it, no systems of prevention and investigation are likely fully to succeed. But if the culture demands integrity and works to ensure it, those systems will be more productive.

Forms of Corruption

Narcotics-Related Corruption:

The most serious corruption problems within the Department arise from the narcotics trade. The traditional unwritten rule of twenty years ago that narcotics graft is "dirty money" has disappeared. The explosion of the cocaine and crack trade that began in the 1980s provides police officers with plentiful opportunities to steal money, drugs, and other property from drug dealers who are unlikely to complain, and to associate with drug dealers who will pay handsomely for police protection.

Unlike a generation ago, when narcotics corruption was confined to units of plainclothes narcotics officers, today's narcotics corruption primarily involves the uniformed patrol force. Nonetheless, even the most elite units of the Department are not immune to narcotics corruption. For example, two detectives assigned to the New York Drug Enforcement Task Force recently pleaded guilty and were convicted of drug trafficking charges in connection with their attempt to sell narcotics lawfully seized in a large-scale narcotics investigation.

Police officers profit from the narcotics trade in a variety of ways, from petty thefts and shakedowns of street dealers to using their police powers to protect and assist large-scale drug organizations in return for sizeable payoffs. The primary forms of narcotics-related corruption we discovered -- which officers often carried out while on duty and in uniform -- include the following:

• Providing assistance and protection to narcotics organizations for payoffs, including selling confidential information, providing protection for transportation of drugs and drug money, harassing competitive dealers, and becoming active entrepreneurs in drug rackets;

• Thefts, sometimes violent, of drugs, money, and firearms from drug dealers;

• Thefts of drugs, money and property seized as evidence;

• Robberies of drug dealers;

• Burglaries of drug locations;

• Selling narcotics, which officers often obtained through theft or as payment from dealers, including sales to other officers, or dealers from whom the drugs were stolen; and

• Selling illegally seized weapons -- including sales of guns to drug dealers.

Narcotics corruption rarely involves a single police officer taking advantage of an isolated opportunity to "score" money, drugs, or both. Rather, it usually involves groups of police officers, acting with various degrees of organization, actively seeking opportunities to score from drug dealers through protection rackets, larceny, extortion, burglary, or robbery.

One Commission investigation, for example, revealed a group of ten to twelve patrol officers assigned to a Brooklyn precinct who, for at least two years, regularly broke into drug locations to steal money, drugs, and firearms. They communicated with each other by using code names over Department radios to arrange clandestine meetings and to plan their illegal raids. Once they had selected a location, they assigned each other roles to perform in the raid and later split stolen cash either in or around the stationhouse or at secret off-duty locations. Similar patterns exist in other precincts as well.

Narcotics corruption among police officers does not end with efforts to score from the drug trade. Personal drug use, especially the use of cocaine and steroids, has also become a significant problem among police officers, even those who may not otherwise engage in other kinds of wrongdoing. While the Commission continues to inquire into the extent of this problem, information from corrupt officers, honest officers, and Department health services officials indicates that the problem has grown over recent years, spurring the Department to significantly increase the frequency of random drug tests in 1993.

Police Violence:

Police corruption investigations typically ignore police violence. This Commission rejected that traditional course because we found that police violence is a serious problem confronting the Department, and may indicate an officer's willingness to engage in corruption. The traditional distinction between corruption and brutality, therefore, no longer applies. Thus any investigation of corruption would be remiss in overlooking brutality.

A number of officers have told us that they were "broken in" to the world of corruption by committing acts of brutality; it was their first step toward other kinds of corruption. A willingness to abuse people in custody or others who challenge police authority can be a way to prove that an officer is a tough cop who can be trusted and accepted by fellow officers. Brutality, like other kinds of misconduct, thus sometimes serves as a rite of initiation into aspects of police culture that foster corruption.

No one would deny that the use of force is often a necessity -- and indeed often crucial to protect an officer's life in the line of duty. We found, however, that the use of force sometimes exceeds the bounds of necessity. Some police officers use violence gratuitously: to demonstrate their preeminence on the streets; to administer on-the-spot retribution for crimes they believe will go unpunished by the courts; and for power and thrills. We also found that such behavior is widely tolerated in the Department.

The Civilian Complaint Review Board is responsible for investigating excessive force allegations. However, the Department has failed to carry out its duty to aggressively prevent and uncover acts of brutality, to hold supervisors accountable for failing to pursue signs of unnecessary violence on their watch, and to solicit information about brutality from other officers or the public.

Perjury, False Statements and Records:

Falsifying Department records and making false statements is not uncommon among certain police officers, even among those who do not engage in other kinds of misconduct. Most often, police falsifications are made to justify an unlawful arrest or search that would otherwise not survive in court, especially in cases of drug or firearms possession; to conceal other corrupt activities; or to excuse the use of excessive force.

Police officers also falsify records to inflate arrest numbers, to enhance arrest charges, to allow seizure of otherwise unseizable evidence, to increase overtime, and to defend their own conduct and the conduct of fellow officers in corruption and excessive force investigations. Superior officers often do little to deter these practices. Indeed, in at least one case, a superior officer went so far as to direct subordinates to falsify official reports for self-serving or, for what were believed to be, legitimate law enforcement purposes.

The consequence of perjury and falsification can be devastating. It can mean that defendants are unlawfully arrested and convicted, that inadmissible evidence is admitted at trial, and ultimately the public trust in even the most honest officer is eroded. This erosion of trust causes the public to disbelieve police testimony resulting in the guilty being set free after trial.

II. THE FAILURES OF THE DEPARTMENT'S CORRUPTION CONTROLS

The Commission found a deep-rooted institutional reluctance to uncover corruption in the Department. This was not surprising. Powerful forces discourage the Department from sustaining efforts to uncover corruption -- which is why an external force is needed to maintain a sense of commitment and accountability.

Police managers ask a great deal of their officers. They ask them to be alert, ready, and available to respond to whatever citizens demand from them; to be courteous and fair no matter how offensive or provocative the behavior of the citizens they encounter; and to be ever willing to face danger to protect the people of our City. Because they must ask for so much from their officers, they rightly judge that they should offer trust, support and loyalty in exchange.

Unfortunately, one of the easiest ways that the Department can show trust and support for its officers is to be less than zealous in efforts to control and uncover corruption. Pursuing corruption -- taking the complaints of citizens (even drug dealers) seriously, using tough investigative methods to determine the truth of allegations, and using pro-active measures to search out corruption -- will be perceived by some as a lack of trust and thus lower morale.

The top management of the Department also understands that revelations of corruption will be dealt with harshly in the court of public opinion. When corruption is uncovered, the press and the public invariably take it as a symptom of a larger problem and a failure of management. Thus, police commanders perceive that their careers may be harmed, and that public confidence will erode, thus jeopardizing the Department's effectiveness in fighting crime.

As a result, top management believed that it would get no reward, and pay a heavy price, for vigilance against corruption. It is no wonder that over time the Department tends to relax its vigilance, and may even throw up roadblocks to uncovering corruption.

Without constant management attention to preventing corruption, however, corrupt officers feel they can act with impunity, honest officers are more vulnerable to the code of silence, and leadership is more easily drawn to other priorities.

This appears to have happened in the Department. From the top brass down to local precinct commanders and supervisors, there was a pervasive belief that uncovering serious corruption would harm careers and the reputation of the Department. There was a debilitating fear of the embarrassment and loss of public confidence that corruption headlines would bring.

As a result, avoiding scandal became more important than fighting corruption. Daniel Sullivan, the six-year chief of the Department's anti-corruption division, testified at the Commission's public hearings that:

... the Department [was] paranoid over bad press. Everything that IAD did reflected poorly on the rest of the Department and generated bad press. So when I went up with the bad news that two cops were going to be arrested ... I felt like they wanted to shoot me because I was always the bearer of the bad news. They were interested primarily in getting good press ... there was a message that went out to the field that maybe we shouldn't be so aggressive in fighting corruption because the Department just does not want bad press.

Numerous officers expressed similar fears of exposing serious corruption.

The reluctance to uncover and effectively investigate corruption infected the entire anti-corruption apparatus, from training, supervision and command accountability to investigations and intelligence gathering. Our investigation revealed an anti-corruption system that was more likely to conceal corruption than uncover it, and a Department often more interested in the appearance of integrity than its reality. Oversight of anti-corruption efforts was virtually non-existent; intelligence gathering efforts were negligible; corruption investigations were often deliberately limited and prematurely closed; and Integrity Control Officers and supervisors were denied the tools needed to uncover corruption and, in practice, played virtually no role in corruption control efforts.

And perhaps most alarming, in a Department known for its high levels of performance, investigative ingenuity, and managerial expertise, no one seemed to care. Despite the importance of its corruption-fighting mandate, the Department allocated little of its billion-dollar-plus budget to anti-corruption efforts. Moreover, although performance in most divisions in the Department is carefully scrutinized at several levels, neither IAD nor other units or supervisors responsible for fighting corruption were held accountable for their performance.

Nor did anyone in the Department know how the Department's anti-corruption efforts had been functioning until this Commission commenced its audit and investigation of the principal components of those anti-corruption efforts. What was known was that the Department's anti-corruption systems were not working well. But that was acceptable, if not preferable: ineffectiveness minimized the likelihood of embarrassment, scandal and a perceived loss of public confidence. Totally overlooked was the public's loss of confidence in the integrity of the Department and the debilitating impact upon the Department's moral fiber.

This is precisely why the past failures of the Department's anti-corruption efforts are so important -- and illuminating. They show the inevitable consequence of leaving anticorruption efforts and oversight solely within the control of the very Department that believes it will be embarrassed and harmed by the success of those efforts.

A brief summary of our preliminary findings on these failures follows.

The Department Abandoned Its Responsibility To Ensure Integrity: The Department failed to impress upon its members that fighting corruption must be one of the Department's highest priorities. The Department devoted insufficient resources, personnel, effort, and planning to preventing and uncovering corruption. Officers of all ranks told us that the general feeling in the Department was that it was better not to know about, much less report, corruption. A "see no evil, hear no evil" mentality often governed supervisors, patrol officers, and even corruption investigators.

The Department Failed to Address Aspects of Police Culture That Foster Corruption: Despite overwhelming evidence of a widespread tolerance of corruption and violence, the Department failed to address police attitudes and practices that foster corruption, and to inculcate attitudes that discourage it. Officers and supervisors were neither encouraged nor rewarded for taking stands against corruption; nor were penalties imposed for being silent or willfully blind to corruption; and officers and supervisors were rarely held accountable for corruption about which they were, or should have been, aware.

The Department Had a Fragmented Approach To Corruption Control: Combatting police corruption requires a coherent, integrated strategy, and coordinated effort and attention on several fronts. These would include, at a minimum, intelligent recruitment; thorough training; effective supervision; strong accountability; thorough investigations; effective intelligence gathering and analysis; meaningful discipline; and vigilant oversight. The Department had no such integrated strategy, and the various parts of what should have been a coordinated system were either non-existent or unproductive.

The System of "Command Accountability" Collapsed: A prime component of the Department's capacity to prevent and uncover corruption is the principle of command accountability: that all commanders are responsible for pursuing corruption in their commands; that they will be evaluated firmly but fairly on their anti-corruption performance; and will be furnished with the tools and resources necessary to do so. In the past, field commanders had Field Internal Affairs Units ("FIAUs") to investigate corruption in their commands. The FIAUs were accountable both to the field commander and to IAD.

Only the skeleton of this system now remains. Its animating principle -- that all commanders must act, and will be held accountable for acting, against corruption -- has disappeared. There is a widespread perception among commanders and supervisors that uncovering corruption on their watch leads to punishment rather than reward.

We found a total lack of commitment to the principle of command accountability. This was allowed to happen because no formal institutional mechanisms were ever adopted to ensure its perpetuation and enforcement. Its success depended on the commitment of the Department's top commanders. When that commitment eroded, so too did the centerpiece of the Department's anti-corruption systems.

The Department Allowed the FIAUs to Collapse: Although the FIAUs were purportedly the backbone of the Department's investigative efforts, they were denied the resources and personnel required to do their job. Moreover, although the FIAUs depended largely on IAD's assistance and oversight, IAD rarely assisted or even cooperated with the FIAUs. In fact, IAD often thwarted FIAU investigations by withholding critical information and resources.

Even worse, the Department permitted IAD to use the FIAUs as a dumping ground for corruption allegations. IAD assigned the poorly resourced FIAUs a caseload that FIAU officers of all ranks testified was so overwhelming it was impossible to handle. As a result, a large number of corruption cases filed with the Department each year -- including over a dozen investigations involving Michael Dowd -- were closed as unsubstantiated without appropriate investigative steps ever having been taken.

The Internal Affairs Division Abandoned Its Mission: IAD abandoned its primary responsibilities to investigate serious and complex corruption cases; to uncover patterns of corruption through trend analysis and self-initiated investigations; and to oversee and assist the FIAUs. For example, IAD assigned itself a caseload of largely easy cases, including cases like sleeping on the job; failed to solicit significant information through its undercover program; initiated no self-generated investigations during at least the past five years, despite an entire unit purportedly dedicated to that task; and relied on a large number of investigators with no prior investigative experience, many of whom never took the required investigations training course.

Consequently, as the Commission uniformly heard from officers of a variety of ranks, IAD was viewed with contempt by members of the Department, and failed to serve as a deterrent to corruption.

The Department Used A Badly Flawed Investigative Approach For Police Corruption: Investigations into police corruption purposefully minimized the likelihood of uncovering the full extent of corruption. Interestingly, the Department's investigations excelled in every area except police corruption. The Commission uncovered a pattern of cases that were prematurely closed and failed to employ basic investigative techniques (like the use of undercovers, sting operations, and turn-arounds) that are routinely relied on in other investigative divisions of the Department. Moreover, IAD operated as a solely reactive investigative division that responded only to isolated complaints rather than patterns of corruption. IAD also fragmented what should have been large-scale investigations by sending out related allegations as separate investigations. Thus, IAD knowingly ignored opportunities to develop investigations of large-scale corruption.

Corruption Cases Were Concealed: IAD and the Inspectional Services Bureau Chief had unbridled discretion to control police corruption investigations and decide what allegations should be officially recorded and sent to prosecutors. We found evidence of abuse of that power. For example, certain corruption cases were kept out of IAD's regular filing system and concealed from prosecutors through a file called the "Tickler File."

The Department's Intelligence Gathering Efforts Were Flawed: The Department made virtually no effort to solicit information from the public, police officers, or other sources of information -- even though such efforts are crucial to uncovering information about police corruption. The Department made little effort to generate information about corruption in the absence of a complaint. It rarely used directed integrity tests and often failed to pursue information from its own field associates, one of the Department's best resources for reliable information about corruption. The Department's complaint in-take efforts also minimized the likelihood of obtaining information on corruption: The Department's "Action Desk" -- which receives and processes information on police corruption -- routinely discouraged individuals from providing information. Department statistics, therefore, vastly underestimate the nature and extent of corruption, and investigations reach only small portions of a much wider problem.

Supervision Was Diluted and Ineffective: Although effective first-line supervision is critical in the fight against corruption, few first-line supervisors perceived corruption control as an important responsibility. The Department did little to suggest otherwise. Even supervisors bent on ensuring integrity often lacked the resources or time to do so. In many precincts, supervisors were responsible for so many officers or so large an area that effective supervision was impossible. Department commanders often assigned supervisors without regard to prior experience, training, or the needs of the command. Inexperienced, probationary sergeants were often assigned to busy, corruption-prone precincts where experienced, proven supervisors are most needed. Thus, in many busy, crime-ridden precincts corrupt officers felt they had free rein. While no amount of supervision will stop all determined offenders, a reasonable level of committed supervision is essential to deter corruption.

Recruit and In-Service Integrity Training Was Neglected: Integrity training has been long neglected by the Department. Insufficient attention was devoted to integrity training at the Police Academy, and "required" in-service integrity training for officers and supervisors was often not provided. When training was offered, it relied largely on obsolete materials and films that remained largely unchanged since the days of the Knapp Commission, and rarely captured serious attention either from recruits or veteran officers.

Effective Deterrence Was Absent: Effective general and specific deterrence was lacking. The likelihood of detection and punishment was minimal, as was the severity of the sanction imposed. Indeed, one method of dealing with corruption was simply to transfer problem officers to unattractive assignments including, crime-ridden precincts. This "dumping ground" method of discipline punishes the community more than the problem officers by assigning them to the very precincts where the opportunities for corruption most abound, where the need for talented, committed officers is the greatest, and where minority populations often reside.

Drug and Alcohol Abuse Policies Were Ineffective: Despite evidence of a serious drug and alcohol problem confronting the Department, little was done to prevent, treat, or uncover the full extent of this problem. Abuse problems are often ignored or mishandled, certain drug tests are given too infrequently, many testing procedures are easy to circumvent, and effective drug treatment is non-existent.

III. PRINCIPAL RECOMMENDATIONS

Most of the failures of the Department's corruption controls could have been prevented, identified, or remedied years ago if the Department had been accountable to regular independent review of its anti-corruption systems. History strongly suggests that the erosion of the Department's corruption control efforts is an inevitable consequence of its institutional reluctance to uncover corruption -- unless some countervailing power forces the Department to do what it naturally strays from doing. This is true of many organizations. It is unrealistic to expect otherwise from the Department. The mere establishment of this independent Commission created such a countervailing pressure, as did the creation of the Knapp Commission twenty years ago. After the creation of this Commission, Police Commissioner Raymond W. Kelly made a number of laudable reforms in the Department's anti-corruption apparatus. It is no coincidence that it was only under the scrutiny of oversight Commissions that there was a heightened vigilance and commitment to anticorruption efforts in the Department. Our challenge is to sustain that vigilance so that history does not again repeat itself.

The Commission believes that the Department must remain responsible for effectively policing itself and for keeping its own house in order. This requires that the Department have effective internal corruption controls to prevent and uncover corruption. The Commission also believes that it is impossible for the Department to bear that responsibility alone. The Department is subject to powerful internal pressures to avoid uncovering corruption, which are almost certain to prevail absent external scrutiny.

The Commission therefore urges a dual-track approach to improving police corruption controls. The first track focuses on the Department's entire internal apparatus for the control of corruption. Police Commissioner Kelly has made important inroads to strengthening this internal apparatus, and he should be commended for his efforts. His principal reforms, however, focus largely on strengthening and centralizing investigative efforts, rather than on prevention, root causes, and conditions. The Commission's final report will make detailed recommendations for internal reforms on a variety of fronts, including:

• improving screening and recruitment;

• improving recruit education and in-service integrity training;

• attacking corruption and brutality tolerance;

• challenging other aspects of police culture and conditions that breed corruption and brutality;

• revitalizing and enforcing command accountability;

• strengthening first-line supervision;

• enhancing sanctions and disincentives for corruption and brutality;

• strengthening intelligence-gathering efforts;

• preventing, detecting, and treating drug and alcohol abuse;

• soliciting police union support for anti-corruption efforts;

• minimizing the corruption hazards of community policing; and

• legislative reforms, including the issue of residency requirements.

The second track focuses on the creation of an independent, external monitor to ensure that the Department's commitment to preventing corruption is sustained and that its internal systems for pursuing corruption operate effectively. It is this external monitor that will be the focus of this interim report.

The External Monitor

The Commission urges the immediate establishment of a permanent external monitor, independent of the Department, to assess the effectiveness of the Department's systems for detecting, preventing, and investigating corruption; to evaluate Department conditions and values that affect the incidence of police corruption; to conduct continual audits of the state of corruption within the Department; and, when appropriate, to make recommendations for improvement. The monitor will issue periodic reports on its findings and recommendations to the Mayor and the Police Commissioner.

This monitor will also serve as a management tool for the Police Commissioner. It will ensure that the Department's anti-corruption systems work effectively -- and that under his or her tenure, the Department will not fall victim to the institutional pressures that erode anti-corruption efforts.

Monitoring Performance of Anti-Corruption Systems

The monitor will:

• ensure that the Department has effective methods for receiving and recording corruption allegations and analyzing corruption trends;

• assess the sufficiency and quality of investigative resources and personnel;

• ensure that the Department employs effective methods and management in conducting corruption investigations, including that it no longer solely relies on a reactive investigative system that narrowly focuses on isolated complaints and that rarely employs pro-active investigative techniques;

• ensure that the Department has successful intelligence-gathering efforts, including effective undercover, field associate, integrity testing, and community outreach programs;

• evaluate the Department's efforts to revitalize and enforce command accountability;

• ensure that the Department strengthens supervision, including levels and quality of first-line supervision, training of supervisors, and consideration of integrity history in determining assignments and promotions;

• require the Department to produce reports on police corruption and corruption trends including, analysis of the number of complaints investigated and the disposition of those complaints, the number of arrests and referrals for prosecution, and the number of Department disciplinary proceedings and the sanctions imposed; and

• conduct performance tests and inspections of the Department's anti-corruption units and programs to guarantee that the Department continually maximizes its capacity to police itself.

The monitor must also have its own investigative capacity to successfully carry out its audits of the Department's internal controls. It will conduct its own self-initiated corruption investigations, intelligence-gathering efforts, and integrity tests to the extent necessary to test the Department's performance. This capacity is not meant to replace the Department's or prosecutors' own investigations or to serve an enforcement purpose, but to ensure that the Department's intelligence-gathering and investigative efforts are focused on areas where corruption is likely to exist.

This investigative capacity is crucial to successfully carrying out the monitor's principal task of auditing and evaluating the Department's anti-corruption efforts. It was only by having such an investigative capacity that this Commission was able to uncover many of the deficiencies in the Department's intelligence gathering, investigative and supervisory efforts, and to determine that the nature and extent of corruption was far more serious than suggested by the Department's official position on corruption.

Monitoring Cultural Conditions

The monitor must also:

• ensure that the Department makes effective efforts to reform the conditions and attitudes that nurture and perpetuate corruption and brutality;

• assess the effectiveness of recruit education, integrity training, field training operation, and the integrity standards set by supervisors;

• ensure that the Department works to eliminate corruption and brutality tolerance and the code of silence;

• evaluate Department efforts to pursue and uncover brutality and its connection to corruption;

• determine whether the Department routinely assigns officers with discipline problems only to certain commands within the Department, such as high-crime, minority precincts, and to determine the impact of such practices;

• evaluate the effectiveness of the Department's drug and alcohol abuse policies, and prevention treatment, and detection efforts;

• evaluate the Department's efforts to overcome police attitudes that isolate them from the public and often create the appearance of a hostile and corrupt police force; and

• enhance liaison efforts with community groups and precinct community councils to provide the Department with input from the public about their perception and information about police corruption and to obtain information for the monitor's recommendations for reform.

Recommendations

We recommend that the Mayor establish a permanent Police Commission headed by three to five highly reputable and knowledgeable citizens appointed by the Mayor who would be willing to serve pro bono. We further recommend that the Commissioners have a limited, staggered term to guarantee turnover, avoid staleness, and prevent the development of a long-term bureaucratic relationship with the Department that could compromise the Commission's independence.

To accomplish its tasks, the Commission's powers should include: the power to subpoena witnesses and documents, unrestricted access to Department records and personnel; the power to administer oaths and take testimony in private and public hearings; and the power to grant use immunity. We do not recommend the creation of a large and costly bureaucracy. With the aforementioned powers, the Commission could perform its work with a small staff of people with varied expertise, including attorneys, investigators, police management experts, and organizational and statistical analysts.

The Police Commission should cooperate with the Police Commissioner in establishing a total commitment to maintaining integrity and the corruption fighting capacity of the Department. It should monitor the implementation of a system of accountability throughout the Department enforced by a program of incentives and disincentives. The Police Commission should cooperate with the Police Commissioner in redefining police culture to reflect the identity of interest between the members of the public and the Department with emphasis on the infusion of mutual respect.

Conclusion

It is the Commission's hope that this interim report will assist the Mayor, the Police Commissioner, and the people of New York City in addressing the problems of police corruption, and the reforms necessary to combat it effectively today and in the future.

Commission To Investigate Allegations of Police Corruption And The Anti-Corruption Procedures of the Police Department

Commissioners

Milton Mollen, Chair

Harold Baer, Jr.

Herbert Evans

Roderick C. Lankler

Harold Tyler

Commission Staff

Joseph P. Armao, Chief Counsel

Leslie U. Cornfeld, Deputy Chief Counsel

Brian Carroll, Director of Investigations

Robert Machado & Frank O'Hara, Deputy Chief Investigators

Counsel

David A Burns

Edward Cunningham

Charles M. Guria

Jeffrey Zimmerman

Director of Media Relations

Torn Kelly

Support Staff

Nancy Levine

Anne Sherlock

Lourdes Sinisterra

Investigators and Analysts

Frances Alexander

Marilyn Coleman

Marcia DeLeon

Alfred Fernandez

Jose Guzman

Thomas Hopkins

Brian T. Kelly

Frank Luce

Samuel Nieves

Jody Pugach

Charmaine Raphael

Dorice J. Shea

Gregory A Thomas

Special Counsel

Jonny J. Frank

William Goodstein

Volunteer Attorneys

Charles King

Thomas M. Obermaier

_______________

Notes:

1. Corruption today is not limited to these types of crimes, as our final report will make clear. Some officers continue to accept and solicit gratuities from business owners, tow-truck operators and the like. These corrupt practices should not be ignored. As officers repeatedly told us, serious corruption often begins with more minor misconduct and corruption. This interim report, however, focuses only on the more serious forms of corruption we uncovered.