by James Petras

Rebelión

5 December 2001

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Introduction

The CIA uses philanthropic foundations as the most effective conduit to channel large sums of money to Agency projects without alerting the recipients to their source. From the early 1950s to the present the CIA's intrusion into the foundation field was and is huge. A U.S. Congressional investigation in 1976 revealed that nearly 50% of the 700 grants in the field of international activities by the principal foundations were funded by the CIA (Who Paid the Piper? The CIA and the Cultural Cold War, Frances Stonor Saunders, Granta Books, 1999, pp. 134-135). The CIA considers foundations such as Ford "The best and most plausible kind of funding cover" (Ibid, p. 135). The collaboration of respectable and prestigious foundations, according to one former CIA operative, allowed the Agency to fund "a seemingly limitless range of covert action programs affecting youth groups, labor unions, universities, publishing houses and other private institutions" (p. 135). The latter included "human rights" groups beginning in the 1950s to the present. One of the most important "private foundations" collaborating with the CIA over a significant span of time in major projects in the cultural Cold War is the Ford Foundation.

This essay will demonstrate that the Ford Foundation-CIA connection was a deliberate, conscious joint effort to strengthen U.S. imperial cultural hegemony and to undermine left-wing political and cultural influence. We will proceed by examining the historical links between the Ford Foundation and the CIA during the Cold War, by examining the Presidents of the Foundation, their joint projects and goals as well as their common efforts in various cultural areas.

Background: Ford Foundation and the CIA

By the late 1950s the Ford Foundation possessed over $3 billion in assets. The leaders of the Foundation were in total agreement with Washington's post-WWII projection of world power. A noted scholar of the period writes: "At times it seemed as if the Ford Foundation was simply an extension of government in the area of international cultural propaganda. The foundation had a record of close involvement in covert actions in Europe, working closely with Marshall Plan and CIA officials on specific projects" (Ibid, p.139). This is graphically illustrated by the naming of Richard Bissell as President of the Foundation in 1952. In his two years in office Bissell met often with the head of the CIA, Allen Dulles, and other CIA officials in a "mutual search" for new ideas. In 1954 Bissell left Ford to become a special assistant to Allen Dulles in January 1954 (Ibid, p. 139). Under Bissell, the Ford Foundation (FF) was the "vanguard of Cold War thinking".

One of the FF first Cold War projects was the establishment of a publishing house, Inter-cultural Publications, and the publication of a magazine Perspectives in Europe in four languages. The FF purpose according to Bissell was not "so much to defeat the leftist intellectuals in dialectical combat (sic) as to lure them away from their positions" (Ibid, p. 140). The board of directors of the publishing house was completely dominated by cultural Cold Warriors. Given the strong leftist culture in Europe in the post-war period, Perspectives failed to attract readers and went bankrupt.

Another journal Der Monat funded by the Confidential Fund of the U.S. military and run by Melvin Lasky was taken over by the FF, to provide it with the appearance of independence (Ibid, p. 140).

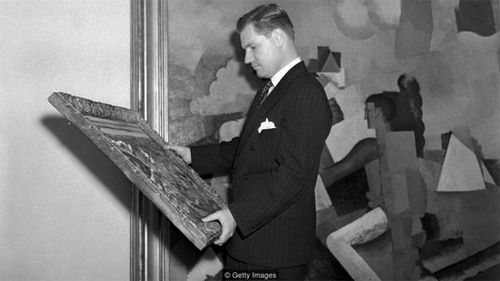

In 1954 the new president of the FF was John McCloy. He epitomized imperial power. Prior to becoming president of the FF he had been Assistant Secretary of War, president of the World Bank, High Commissioner of occupied Germany, chairman of Rockefeller's Chase Manhattan Bank, Wall Street attorney for the big seven oil companies and director of numerous corporations. As High Commissioner in Germany, McCloy had provided cover for scores of CIA agents (Ibid, p. 141).

McCloy integrated the FF with CIA operations. He created an administrative unit within the FF specifically to deal with the CIA. McCloy headed a three person consultation committee with the CIA to facilitate the use of the FF for a cover and conduit of funds. With these structural linkages the FF was one of those organizations the CIA was able to mobilize for political warfare against the anti-imperialist and pro-communist left. Numerous CIA "fronts" received major FF grants. Numerous supposedly "independent" CIA sponsored cultural organizations, human rights groups, artists and intellectuals received CIA/FF grants. One of the biggest donations of the FF was to the CIA organized Congress for Cultural Freedom which received $7 million by the early 1960s. Numerous CIA operatives secured employment in the FF and continued close collaboration with the Agency (Ibid, p. 143).

From its very origins there was a close structural relation and interchange of personnel at the highest levels between the CIA and the FF. This structural tie was based on the common imperial interests which they shared. The result of their collaboration was the proliferation of a number of journals and access to the mass media which pro-U.S. intellectuals used to launch vituperative polemics against Marxists and other anti-imperialists. The FF funding of these anti-Marxists organizations and intellectuals provided a legal cover for their claims of being "independent" of government funding (CIA).

The FF funding of CIA cultural fronts was important in recruiting non-communist intellectuals who were encouraged to attack the Marxist and communist left. Many of these non-communist leftists later claimed that they were "duped", that had they known that the FF was fronting for the CIA, they would not have lent their name and prestige. This disillusionment of the anti-communist left however took place after revelations of the FF-CIA collaboration were published in the press. Were these anti-communist social democrats really so naive as to believe that all the Congresses at luxury villas and five star hotels in Lake Como, Paris and Rome, all the expensive art exhibits and glossy magazines were simple acts of voluntary philanthropy? Perhaps. But even the most naive must have been aware that in all the Congresses and journals the target of criticism was "Soviet imperialism" and "Communist tyranny" and "leftist apologists of dictatorship" -- despite the fact that it was an open secret that the U.S. intervened to overthrow the democratic Arbenz government in Guatemala and the Mossadegh regime in Iran and human rights were massively violated by U.S. backed dictators in Cuba, Dominican Republic, Nicaragua and elsewhere.

The "indignation" and claims of "innocence" by many anti-communist left intellectuals after their membership in CIA cultural fronts was revealed must be taken with a large amount of cynical skepticism. One prominent journalist, Andrew Kopkind, wrote of a deep sense of moral disillusionment with the private foundation-funded CIA cultural fronts. Kopkind wrote:

"The distance between the rhetoric of the open society and the reality of control was greater than anyone thought. Everyone who went abroad for an American organization was, in one way or another, a witness to the theory that the world was torn between communism and democracy and anything in between was treason. The illusion of dissent was maintained: the CIA supported socialist cold warriors, fascist cold warriors, black and white cold warriors. The catholicity and flexibility of the CIA operations were major advantages. But it was a sham pluralism and it was utterly corrupting" (Ibid, pp. 408-409)."

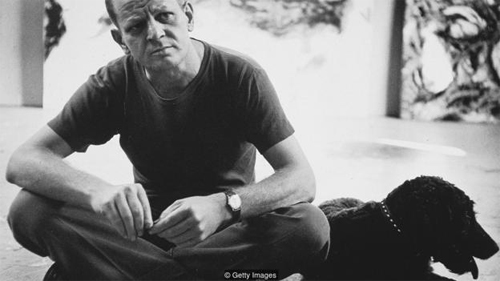

When a U.S. journalist Dwight Macdonald who was an editor of Encounter (a FF-CIA funded influential cultural journal) sent an article critical of U.S. culture and politics it was rejected by the editors, working closely with the CIA (Ibid, pp. 314-321). In the field of painting and theater the CIA worked with the FF to promote abstract expressionism against any artistic expression with a social content, providing funds and contacts for highly publicized exhibits in Europe and favorable reviews by "sponsored" journalists. The interlocking directorate between the CIA, the Ford Foundation and the New York Museum of Modern Art lead to a lavish promotion of "individualistic" art remote from the people -- and a vicious attack on European painters, writers and playwrights writing from a critical realist perspective. "Abstract Expressionism" whatever its artist's intention became a weapon in the Cold War (Ibid, p. 263).

The Ford Foundation's history of collaboration and interlock with the CIA in pursuit of U.S. world hegemony is now a well-documented fact. The remaining issue is whether that relationship continues into the new Millenium after the exposures of the 1960s? The FF made some superficial changes. They are more flexible in providing small grants to human rights groups and academic researchers who occasionally dissent from U.S. policy. They are not as likely to recruit CIA operatives to head the organization. More significantly they are likely to collaborate more openly with the U.S. government in its cultural and educational projects, particularly with the Agency of International Development.

The FF has in some ways refined their style of collaboration with Washington's attempt to produce world cultural domination, but retained the substance of that policy. For example the FF is very selective in the funding of educational institutions. Like the IMF, the FF imposes conditions such as the "professionalization" of academic personnel and "raising standards." In effect this translates into the promotion of social scientific work based on the assumptions, values and orientations of the U.S. empire; to have professionals de-linked from the class struggle and connected with pro-imperial U.S. academics and foundation functionaries supporting the neo-liberal model.

As in the 1950s and 60s the Ford Foundation today selectively funds anti-leftist human rights groups which focus on attacking human rights violations of U.S. adversaries, and distancing themselves from anti-imperialist human rights organizations and leaders. The FF has developed a sophisticated strategy of funding human rights groups (HRGs) that appeal to Washington to change its policy while denouncing U.S. adversaries their "systematic" violations. The FF supports HRGs which equate massive state terror by the U.S. with individual excesses of anti-imperialist adversaries. The FF finances HRGs which do not participate in anti-globalization and anti-neoliberal mass actions and which defend the Ford Foundation as a legitimate and generous "non-governmental organization".

History and contemporary experience tells us a different story. At a time when government over-funding of cultural activities by Washington is suspect, the FF fulfills a very important role in projecting U.S. cultural policies as an apparently "private" non-political philanthropic organization. The ties between the top officials of the FF and the U.S. government are explicit and continuing. A review of recently funded projects reveals that the FF has never funded any major project that contravenes U.S. policy.

In the current period of a major U.S. military-political offensive, Washington has posed the issue as "terrorism or democracy," just as during the Cold War it posed the question as "Communism or Democracy." In both instances the Empire recruited and funded "front organizations, intellectuals and journalists to attack its anti-imperialist adversaries and neutralize its democratic critics. The Ford Foundation is well situated to replay its role as collaborator to cover for the New Cultural Cold War.

James Petras is a Bartle Professor (Emeritus) of Sociology at Binghampton University, New York, and author of: Globalization Unmasked: Imperialism in the 21st Century with Henry Veltmeyer (Zed Books, 2001) James Petras is a frequent CRG contributor. His web site in English is at: http://www.rebelion.org/petrasenglish.htm A superset list of his articles in Spanish is at: http://www.rebelion.org/petras.htm

Copyright James Petras 2001, For fair use only/ pour usage équitable seulement .