Mindfulness Meditation Research: Issues of Participant Screening, Safety Procedures, and Researcher Training

by M. Kathleen B. Lustyk, PhD; Neharika Chawla, MS; Roger S. Nolan, MA; G. Alan Marlatt, PhD

ADVANCES JOURNAL, Spring 2009, VOL. 24, NO. 1

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

M. Kathleen B. Lustyk, PhD, is a professor of psychology, in the School of Psychology, Seattle Pacific University, Washington, and an affiliate associate professor, in Biobehavioral Nursing and Health Systems, University of Washington School of Nursing, Seattle. Neharika Chawla, MS, is a pre-doctoral fellow at the Addictive Behaviors Research Center in the Department of Psychology, University of Washington, Seattle. Roger S. Nolan, MA, is a psychotherapist in Burbank, California. G. Alan Marlatt, PhD, is a professor of psychology and the director of the Addictive Behaviors Research Center, University of Washington

ABSTRACT

Increasing interest in mindfulness meditation (MM) warrants discussion of research safety. Side effects of meditation with possible adverse reactions are reported in the literature. Yet participant screening procedures, research safety guidelines, and standards for researcher training have not been developed and disseminated in the MM field of study. The goal of this paper is to summarize safety concerns of MM practice and offer scholars some practical tools to use in their research. For example, we offer screener schematics aimed at determining the contraindication status of potential research participants. Moreover, we provide information on numerous MM training options. Ours is the first presentation of this type aimed at helping researchers think through the safety and training issues presented herein.

Support for our recommendations comes from consulting 17 primary publications and 5 secondary reports/literature reviews of meditation side effects. Mental health consequences were the most frequently reported side effects, followed by physical health then spiritual health consequences. For each of these categories of potential adverse effects, we offer MM researchers methods to assess the relative risks of each as it pertains to their particular research programs.

The list of benefits associated with mindfulness meditation (MM) is growing. Interest in this ancient practice rooted in Buddhist philosophy seems to know no cultural or religious boundaries. Walsh and Shapiro write, “Meditation is now one of the most enduring, widespread, and researched of all psychotherapeutic methods.”1 Yet, while safety guidelines, participant screening procedures, and standardized researcher training exist for some behavioral medicine practices (eg, exercise per the American College of Sports Medicine [ACSM] guidelines2), these have yet to be developed and disseminated in the MM field of study.

To assist those planning studies of MM, our goals in this paper are to (1) define categories of side effects of meditation with possible adverse reactions raised in the literature and by clinicians with extensive experience in the therapeutic delivery of MM, (2) propose a procedure for screening potential research participants and suggest safety procedures within each category, and (3) reduce the risk of potential iatrogenic harm to research participants by offering suggestions for researcher training in MM. Together, the authors contributing to this paper cover a broad range of expertise, including clinicians who regularly employ MM in their practices, specialists in MM facilitation from the Theravada tradition, and senior research scholars skilled in intervention, laboratory, and behavioral neuroscience methods.

MINDFULNESS MEDITATION DEFINITION

Mindfulness meditation (MM) involves completely attending to experiences on a moment-to-moment basis in an effort to cultivate a nonjudgmental, nonreactive state of awareness.3 MM is rooted in the traditional Buddhist practice of Vipassana, which translates literally as “seeing things as they really are.”4 MM practice begins with sustained observation of the breath and expands to include awareness of physical sensations, thoughts, and emotional states as they arise in the present moment. This focus on present moment experiences trains attitudinal, relational, and cognitive capacities in practitioners with supporting changes in neurobiological substrates.5-7 According to Shapiro,8 this shift in focus from the breath to a variety of phenomena is what distinguishes MM from purely concentrative forms of meditation such as Transcendental Meditation (TM), which uses a mantra to centralize cognitive focus. Still, both MM and TM do involve concentrating on a specific object (eg, the breath); however, with MM this unified focus is then directed toward the entire field of awareness. Although meditation practices vary in the specific techniques employed, all involve a form of mental/attentional training.8,9

This overlap in meditation techniques has recently been addressed by Lutz et al,9 who offer the description of 2 meditation styles, namely focused attention and open monitoring, noting that with MM, practitioners may include both styles in their practices, whereas techniques such as TM primarily involve focused attention. We have considered this overlap in MM styles in our presentation of potential adverse effects by drawing upon MM studies as well as those reporting on related meditation techniques. We posit that when designing a study in an area of research where empirically tested safety procedures and standardized protocols are lacking, it is particularly important to consult the literature for reports of potential adverse effects attributed to the technique under investigation as well as any related techniques to maximize participant safety and facilitator awareness. As this is the case with MM, reports from small-n studies, secondary analyses, and the like involving MM-related forms of mediation warrant consideration. Beyond this, anecdotal evidence from clinicians who have observed negative consequences from MM with their patients is worth considering as well.

Then the Fourth Reliance do not rely on conceptual mind. Rely on nondual wisdom experience. This is an incredibly important one and one that I work with every single day because in these particular times with everything flying around, concepts are flying like crazy. Mine are, I don’t know about yours, my mind looking for a place to land wants to come up with some kind of conclusion or position. But conceptual mind is not reliable, and of course concepts still keep coming up all the time, but can we rely, especially on our nondual wisdom experience as the precious treasure of our lineage, more precious than any conceptual teachings that we may have received. Can we allow ourselves to hold paradoxes, complexity in our experience without trying to boil it down to very simple conclusions at any given moment. What is it like for us to rely on the nondual wisdom of experience? That’s really the challenge. It’s a challenge I’m facing every day. I’m sure a lot of us are....

I want to say that in my years of practicing with the Sakyong and seeing him on his journey, I’ve seen difficult times for him. I’ve seen challenges for him, but in general, the Sakyong depicted in the news stories is not the Sakyong I know. And so maybe I’ve missed something along the way. And it absolutely breaks my heart that there have been women who have been harmed by his conduct and I realize that we as a community did not do enough to take care and to find out what happened with this women. So I hold this paradox in my heart as my path of warriorship. My love and respect for the Sakyong, his teacher and what I’ve gotten from him, and my heartbreak about the harm that has occurred that we as a community, the Sakyong as teacher did not take care of and address. So I just want to say this. Holding this paradox is my path of warriorship that sends me into lots of ups and downs.

-- Judith Simmer-Brown to Distraught Shambhala Members: “Practice More.” (Notes and Transcript), by Matthew Remski

Please note: it was not our intent to evaluate the validity of the stated side effects reported in each of the articles cited herein. Such evaluations would require assessing how predictive each potential adverse outcome was from the meditation performed, how accurate the reporting author’s analyses were, and determination of mitigating circumstances. Our intent was simply to report the possibility of these outcomes so future study designers may be aware of them and plan accordingly.

MINDFULNESS-BASED THERAPEUTIC APPROACHES

MM has been incorporated into various therapeutic interventions. These interventions are associated with beneficial therapeutic effects in cases of chronic pain,10,11 substance use disorders,12-19 depression,20-23 anxiety,24,25 and binge eating disorder. 26,27 Therapeutic interventions that involve formal training in mindfulness skills include Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR),28 Mindfulness-Based Relapse Prevention (MBRP),29,30 Mindfulness-Based Cognitive Therapy (MBCT),31,32 and Mindfulness-Based Eating Awareness Training (MB-Eat).33 Other approaches that incorporate components of mindfulness into their therapeutic tenants include Dialectical Behavior Therapy (DBT)34 and Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT).35

The developers of each of these therapeutic interventions are well-established scholars and skilled healthcare providers. As such, these developers and/or members of their research teams have specific training in patient/participant intake procedures and methods of responding to mental health–related adverse effects. Yet, with the favorable findings being reported with MM interventions, research interest is growing rapidly and, consequently, MM effects are being investigated by members of various guilds including neuroscience, cognitive, social and physiological psychology, medicine, and nursing under the supposition that MM is by-and-large a safe behavioral medicine practice. However, systematic evaluations of its safety have not been reported in the literature. One possibility is that the absence of reported adverse effects is taken as support for MM safety. We posit the following: (1) The absence of reported procedural cautions/warnings, side effects, or adverse events in well-controlled MM clinical trials does not necessarily mean that none exist. (2) Such reporting absence may simply represent the lack of a standard for reporting these issues/events within a new and rapidly growing field of study. (3) Moreover, consent and safety procedures do not routinely get reported in clinical trials, leaving open the possibility that new MM researchers who seek to replicate published procedures may not go into the study fully prepared for what may occur nor include adequate protection for participants. It is this third effect that is our major concern and, hence, the focus of this paper.

CATEGORIES OF POTENTIAL ADVERSE EFFECTS

As demonstrated in Table 1, side effects of meditation with possible adverse reactions do occur. In light of research reports cited in Table 1 and recent reviews that discuss potential negative consequences of meditation, we thought it important to categorize potential adverse effects into (1) mental, (2) physical, and (3) spiritual health considerations. Within each category, we offer examples of specific side effects, cite cautionary reports for potential adverse effects, and label each effect as an absolute contraindication, a relative contraindication, or an issue worthy of consideration. Similar to the rationale applied to assessing safety in exercise research,2 we define an absolute contraindication as a condition or circumstance under which it is inadvisable to include a participant in a research study or carry out the research altogether. With a relative contraindication, participation may be inadvisable under some circumstances but not others. Matters worthy of concern are so named due to the theoretical/anecdotal nature of support for their consideration. To assist researchers in determining contraindication status of potential research participants, we offer step-by-step sample screener schematics to guide researchers as they develop their own research screening protocols.

Category 1: Mental Health Considerations

As can be seen in Table 1, adverse effects on mental health are the most frequently reported negative consequences from meditation. Of those mental health consequences listed in Table 1, the reports of severe affective and anxiety disorders as well as temporary dissociative states and psychosis give primary cause for concern.36-38 One example of a severe anxiety disorder is Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD). PTSD is a diagnosis characterized by the aftermath of a traumatic event (eg, combat, sexual assault), during which a person experiences feelings of intense fear, helplessness, and horror. Symptoms include intrusive recollections and re-experiencing in the form of distressing memories and flashbacks; avoidance of thoughts, feelings and situations associated with the traumatic event; emotional numbing; and hyperarousal.39 Because the practice of MM is contrary to the avoidance that is characteristic of PTSD,40 when individuals initially engage in MM they may, thus, encounter avoided affect and experiences in a form that is extremely distressing (eg, flashbacks, intrusive thoughts and memories) and may put them at risk for potential retraumatization. In order to address contraindication status (eg, absolute, relative, matter worthy of consideration) for participants with a history of trauma or a diagnosis of PTSD, we must first identify the specific research purpose.41 To illustrate, we provide a sample screener schematic for PTSD in Figure 1.

Table 1. Side Effects of Meditation With Possible Adverse Reactions

Source and Study Design / Adverse Effects / Category of Side Effects* / Meditation Type / Meditation Duration/Intensity Description

Castillo43: multiple case study / • In all cases there were reports of Depersonalization, Derealization. Note: 3 of the 6 cases experienced symptoms after extended residential courses / MH / TM / Individual practices (daily frequency/duration not reported) and extended residential courses.

Chan-Ob and Bonnyanarunthee 36: multiple case studya / • Case 1: Reports of psychotic symptoms, including Hallucinations, Fear of persecution, Disorientation, Poor insight and judgment, Reduced food intake (note: patient’s prior history of hypophagia not reported), Insomnia reported as complete sleep loss (note: patient’s prior history of insomnia not reported); • Case 2: Reports of psychotic symptoms, including Hallucinations, Delusions of grandeur, Thought disorder, Loss of appetite (note: patient’s prior history of hypophagia not reported), Inability to sleep (note: patient’s prior history of insomnia not reported) / MH, PH/MH, PH/MH, MH, PH/MH, PH/MH / specific type not reported / Case 1: symptoms reported after a 7-day intensive meditation retreat where it was suggested that one “…meditate all the time” (p 926); Case 2: symptoms reported after 3 consecutive nights of walking meditation throughout the night.

French et al79: single case study / • Feelings of anxiety, Feelings of intense dysphoria, Feelings of mania, including/euphoria/grandiosity, Reports of psychosis-like behavior / MH, MH, MH, MH / TM / Individual practice (daily frequency/ duration not reported)

Jaseja51: review / • Increased epileptogenisis susceptibility / PH / Various methods / This is a theory paper reporting EEG and neurochemical meditation effects.

Kennedy80: multiple case study / • Case 1: Reports of depersonalization and derealization, including Autoscopy, Double vision, Grandiosity/elation; Case 2: Reports of depersonalization and derealization, Feelings of anxiety / MH, MH / MM / Two cases with individual practices. Case 1: meditation described as awareness training and yoga (daily frequency/ duration not reported); Case 2: regular Arica practiceb (reports practice on most days of the week for an unspecified duration)

Lazarus81: multiple case summary / • Feelings of depression, including Attempted suicide following a weekend training course in TM (note: details of the attempt and patient’s history of prior suicide attempts not reported), Feelings of anxiety, including Tension, Restlessness/extreme agitation, Reports of severe depersonalization / MH, MH, MH, PH / TM / The author summarizes a collection of clinical observations precipitated by individual TM practice (daily frequency/duration not reported).

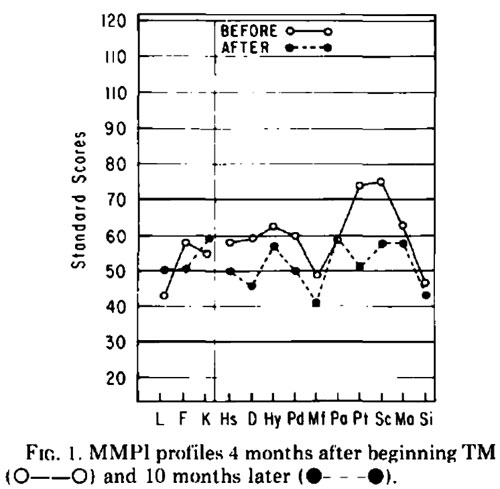

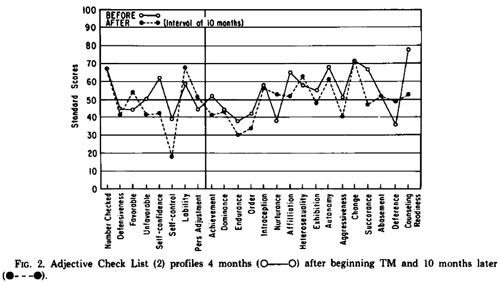

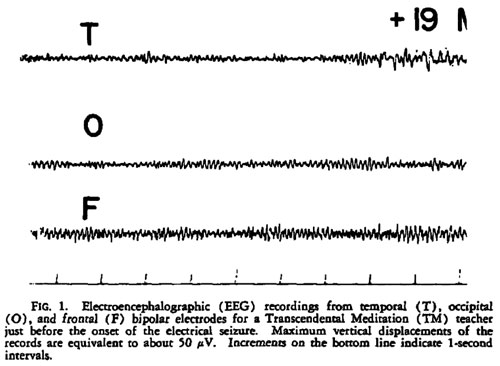

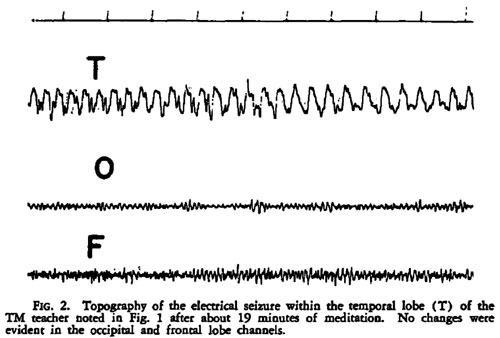

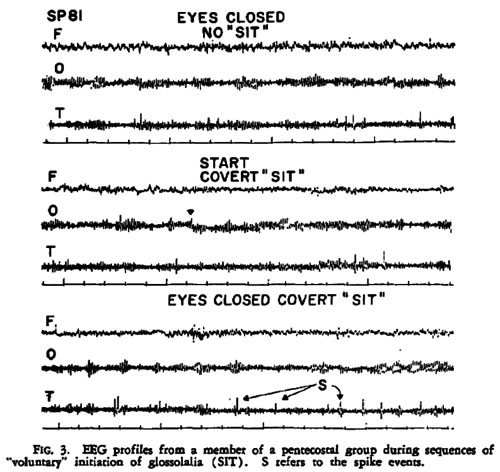

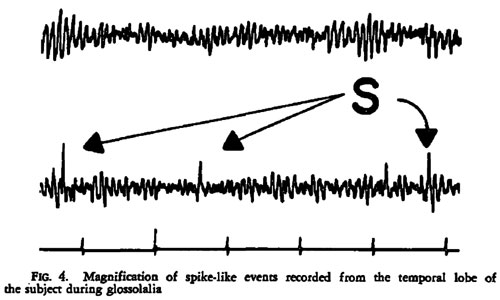

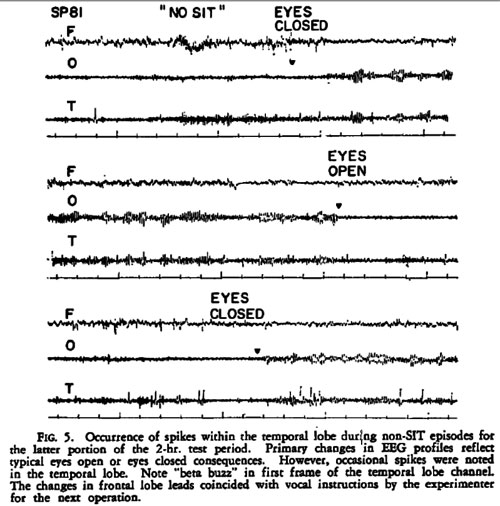

Persinger49: single case study / EEG revealed focal, temporal lobe, epileptic-like electrical changes recorded after 19 minutes of TM. / PH / TM / 10-year TM veteran observed during a 30-minute session

Persinger82: survey study / Significantly more complex partial epileptic-like signs (ascertained from an author generated inventoryc) observed in meditators compared to nonmeditators./ PH / TM / 1081 university students were surveyed; 221 of those surveyed were experienced meditators

Sethi and Bhargava 83: multiple case study / • Case 1: Reports of psychosis, including Delusions of persecutions/reference, Auditory hallucinations; • Case 2: Reports of religious delusions / MH, MH/SH / Type not specified / Case 1 participated in 4 days of intensive meditation in isolation; Case 2 participated in a 6-day residential retreat

Shapiro38: secondary analysis on a convenience sample / • Feelings of depression, including Decreased life motivation/boredom, Increased negativity/self-judgment, Feelings of anxiety, including Panic and/or tension, Feelings of dissociation, including Disorientation/confusion, Feelings of meditation “addiction”, Reports of pain / MH, MH, MH, MH, PH / Vipassana / Residential retreat; 2-week or 3-month duration with formal practice occurring a minimum of 10 hours/day.

VanderKooi84: multiple case study / • Case 1: Report of psychotic break with Hallucinations, Religious delusions; • Case 2: Report of psychosis, including Hallucinations, Intense fear and loneliness; • Case 3: Report of psychosis, including Hallucinations, Religious delusions / MH/SH, MH, MH/SH / Zen, TM, MM / Three cases of psychosis following residential retreats. Case 1: 7-day Zen retreat, Case 2: 10-day Theravada retreat, Case 3: weekend MM retreat.

Yorston85: single case study / • Feelings of mania, including Increased talkativeness, Overactivity/restlessness, Distractible, Sexual disinhibition, Reports of psychotic symptoms, including Thought disorder with flight of ideas, Grandiose delusions, Insomnia involving 5-days of reported sleeplessness (note: prior history of insomnia not reported). / MH, MH / Yoga and Zen (Sesshin) meditation / Yoga was described as a weekend class. Sesshin was described as an intensive weekend event. The patient also participated in a 2-month Zen Buddhist retreat (frequency/duration of daily practice not reported).

*MH=Mental Health, MM=Mindfulness Meditation, PH=Physical Health, SH=Spiritual Health, TM=Transcendental Meditation

aSymptoms for the third case are not reported due to the presence of a known psychotic illness prior to the meditation course. bArica is a multifaceted practice involving kath-channel breathing, mantrams, and yantras (see: http://www.arica.org for more information). cThe Personal Philosophy Inventory47,80 assesses 13 clusters of complex partial epileptic items, which identify temporal lobe phenomenology. In addition to the specific references listed, this table was compiled from the review articles of Arias et al68; Perez-De-Albeniz and Holmes36; Melbourne Academic Mindfulness Interest Group44; Lansky & St. Louis.48

As depicted in Figure 1, if the purpose of the study is to improve symptoms for a clinically diagnosed condition such as PTSD, then the study is classified as a clinical intervention. We posit that it is highly unlikely that such studies would receive Institutional Review Board (IRB) approval or extramural funding without the necessary safety precaution of including a clinician trained to treat PTSD on the research team; this is due to the fact that PTSD is an absolute contraindication under such circumstances. This is not to say that MM interventions for PTSD should not be performed. Support for the contrary comes from reports of beneficial findings from empirically validated treatments for trauma and PTSD that include a MM component.42 We address further positive MM outcomes in our discussion.

If, however, the purpose of the study is to investigate the effects of MM on a subclinical outcome (ie, not a diagnosable condition/illness) or to test an explanatory model (eg, a test of MM mechanisms of action), then including someone with PTSD in this example becomes a relative contraindication and screening at the outset of the study would assess inclusion: Basically, if conditions are met to provide adequate participant safety, such as inclusion of a trained clinician on the research team and obtaining informed consent, then inviting that participant to join the study may be appropriate if he or she meets all other inclusion criteria. For the researcher interested in exploring MM effects who is not clinically trained and does not have a member of their research team who is, we offer another option in our screening protocol (Figure 1) that will provide increased safety for potential participants. The option is to omit participants with mental health concerns such as PTSD in this example.

Figure 1. Sample Screener Schematic for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder as an Example of a Mental Health Consideration for Studies of Mindfulness Meditation Effects

Finally, including a clinically trained person on the research team or having such a person available for consultation and referral throughout the duration of the study may achieve maximum safety in MM research. For each of the mental health consequences listed in Table 1, a screener schematic similar to Figure 1 could easily be generated by replacing PTSD with each condition of concern.

For example, another primary mental health concern associated with meditation as reported in the literature is temporary depersonalization, or feelings of being detached from one’s mental processes or body. Certain types of meditation (eg, concentration practices like TM) have been found to induce depersonalization, possibly due to the related sensory deprivation. 43 Shapiro38 reports on 2 incidences (i.e., 7% of the sample studied) in which attendees at Vipassana retreats experienced severe enough symptoms that they stopped meditating. One had practiced 2 years or less prior to attending a 10-day retreat, which left him “totally disoriented. . .confused, spaced out”38. The other had 7 years or more of practice experience prior to attending a 3-month retreat. In a narrative he provided to the researcher he wrote “the mind set values that the retreat cultivated felt out of sync with the world. [Symptoms included]. . .lots of depression, confusion…severe shaking and energy releasing”38. Still, a recent study by Michal et al44 found an inverse relationship between mindfulness, which was operationally defined by self-reports using the Mindful Attention and Awareness Scale and depersonalization. It is unclear whether this association would generalize to interventions that involve MM practice. Until such time as empirical evidence is available, we offer our screener schematic to guide researchers in assessing contraindication status associated with depersonalization.

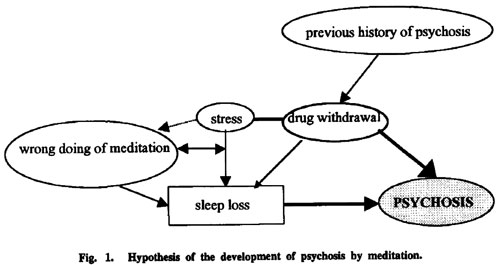

Another primary adverse effect within this mental health category is psychosis, which represents a loss of contact with reality and is characterized by the presence of symptoms including delusions, hallucinations, disorganized speech, and/or disorganized behavior.38 The sensory deprivation and lack of sleep that are sometimes associated with intensive meditation practice may serve as triggers for psychotic episodes among those who are predisposed to such a condition. As can be seen in Table 1, several case reports of psychotic episodes precipitated by meditation exist in the literature. While this may be attributed to meditation intensity, such as participation in residential retreats, the limited and preliminary nature of this evidence warrants a cautious approach to using meditation with individuals predisposed to psychosis. Cautions seem particularly important for individuals with acute psychosis, mania, or suicidality and those noncompliant with prescribed antipsychotic medications. For example, as detailed in Table 1, most reported instances of postmeditation psychosis followed very intensive meditation practices. 36, 83,85 The one report of attempted suicide following an intensive TM training course81 presented in Table 1 is hard to interpret given that the details of the attempt and the patient’s history of prior suicidal attempts are not reported. Thus, the conservative approach to protecting research participants would be to adjust the screener schematic we provide in Figure 1 to assess acute psychosis, mania, or suicidality so that the contraindication status of such individuals can easily be determined.

If proposed study outcomes do not include assessment of mental health, the general consensus among MM investigators is to still screen for mental health concerns as precautions.45 However, we must underscore that no standard exists for this practice nor do all empirical reports published provide details on this screening, leaving open the possibility that an investigator new to this field of research may fail to exercise such precautions. In addition, the means by which researchers determine the current and/or past mental health status of potential research participants is with structured psychiatric interviews. There are a few types of structured interviews available for research purposes such as the Composite International Diagnostic Inventory.46 Interviewer training is a prerequisite to use, in part, because the administration of these interviews is potentially harmful to respondents in and of themselves. For example, to screen for clinical levels of anxiety, participants are asked to recall stressful or potentially traumatic events, and these recollections may produce negative emotional reactions symptomatic of the anxiety condition. As we propose in our screener schematic, adding appropriately trained clinical professionals to the research team would improve participant safety.

Category 2: Physical Health Considerations

As reported in Table 1, adverse effects on physical health are the next most frequently reported negative consequence of meditation; these involve neurological and somatic problems. Based on the extant literature, the neurological concern surrounding meditation is increased epileptogenesis (ie, risk of seizures). Seizures are sudden disruptions in the brain’s electrical activity that give rise to altered consciousness and/or behaviors. Epilepsy is the clinical diagnosis for a condition characterized by recurrent seizures. According to the Epilepsy Foundation of America, more than 3 million Americans suffer from seizure disorders, and it is estimated that 6% of the US population will experience a seizure in their lifetime.47 While often scary to observers, most seizures are not life threatening. Conversely, status epilepticus, or longlasting/ continuous seizure, causes unconsciousness and respiratory distress.48 Moreover, the burden associated with a seizure occurrence extends beyond the actual event in terms of lifestyle limitations (eg, loss of driving privileges).

As reported in Table 1, occurrences of seizures during meditation exist.49,50 An emergent body of literature evinces electroencephalographic (EEG) alterations from meditation including MM. According to Jaseja, meditation-induced neuronal hypersynchrony and neurochemical increases in glutamate and serotonin may decrease the seizure threshold.51 Given that increased cortical gamma wave synchrony has recently been observed during MM in both experienced practitioners52 and meditation novices,5 screening for seizure history in potential MM research participants is warranted to maximize participant safety. Furthermore, the work of Jha et al53 reveals that subsystems of attention including focusing components are implicated in MM. This is noteworthy given that focused attention is epileptogenic54- 56 and is listed by the Epilepsy Foundation of America as a seizure trigger.57

Therefore in Figure 2, we provide a screener schematic for this neurological concern in adults as an example for the physical health considerations category. In instances where the research question involves the use of MM therapeutically for epilepsy, we label this as a neurology study, which would be performed under the care of a physician.

Based on the evidence referenced in Table 1, another physical health consideration with meditation is somatic discomfort or pain. In the manualized mindfulness-based therapies previously mentioned (eg, MBSR), consideration of discomfort is addressed by providing postural options for MM practitioners (eg, the use of a chair rather than sitting on the floor). Furthermore, some forms of MM involve physical activity (eg, walking meditation) that prevents the muscle/joint strain of maintaining a single posture during a MM session. Yet some scholars have begun to consider the need to deconstruct mindfulness-based therapy options in order to systematically investigate efficacy-effectiveness and explanatory models of the meditation components.41 With this movement, new considerations for participant safety are warranted. If, for example, a researcher wishes to systematically investigate the effects of a body-scan form of MM compared to Hatha yoga (a movement form of MM) on an outcome, kinesthetic concerns arise warranting participant screening for neuromuscular/joint-related illnesses negatively affected by maintaining a particular posture through the duration of a MM session.

Figure 2. Sample Screener Schematic for Seizure Disorder/Epilepsy as an Example of a Physical Health Consideration for Studies of Mindfulness Meditation Effects in an Adult Sample

One such neuromuscular/joint-related illness is arthritis, a collective term used to label painful joint diseases. Common forms include rheumatoid arthritis, an autoimmune disease causing chronic pain, inflammation, and stiffness in several joints: and osteoarthritis, which is due to a loss of cartilage between joint bones typically affecting fewer joints more intermittently than the rheumatoid form. Immobility exacerbates both forms of arthritis, while moderate-intensity exercise is associated with symptom improvements.58,59

Sedentary MM results in joints being held in a certain position for up to 30 minutes or more. This may result in uncomfortable kinesthetic sensations (Table 1) from inactivity or fatigue of postural muscles if a certain posture is held for the duration of the practice. This type of discomfort is exacerbated in persons with arthritis,60 so to provide maximum safety for arthritic research participants active forms of MM (eg, walking) are advised. However, if the research goal is to test sedentary MM effects on some other outcome than arthritis symptoms, arthritis should be treated as a relative contraindication and would follow that pathway for screening in our Figure 2 schematic.

As also pointed out in Table 1, physical health concerns included loss of appetite, reduced food intake, and difficulty sleeping. These findings must be interpreted with caution as the reporting authors cited in Table 1 do not provide information on participants’ prior history with hypophagia or insomnia. Moreover, such side effects may not be adverse events. For example, hypophagia may be health promoting if it is the result of reduced anxiety leading to reductions in stress-induced eating.