by Bill Weinberg

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Taken alone, either one of Ken Kesey's claims to fame would have won him that fabled indelible mark in the annals of American culture. The young author of One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest--the 1962 novel whose intransigent anger at authority presaged a cultural explosion--would be remembered today even if he hadn't gone on to actually pioneer, even spark, that very explosion. Or an indispensable element of it. As "The Chief" of the Merry Pranksters, Ken Kesey played the ultimate reality hacker, liberating the secret of LSD from the CIA mind-control laboratories like Prometheus stealing fire from heaven. He let the experiment get out of control, turned on the masses, and almost inadvertently unleashed the psychedelic revolution of the 1960s. Nothing would ever be the same again. And when that wave crested, he became an icon of the search for new rural roots, of applying the lessons of reckless rebellion and experimentation to responsible family life -- without apology or regret. Although, for Kesey, this was really a return to his roots.

Ken Kesey had the redneck creds to break through the harsh cultural limits of post-war America. Of Okie stock, he was born in La Junta, on the Colorado plains, in 1935, and grew up in Springfield, Oregon, where his father became a prosperous dairy farmer. His upbringing was wholesome and vigorous -- wrestling, football, camping, shooting the rapids. He graduated from high school in 1953, voted "most likely to succeed," and enrolled at the University of Oregon, where he concerned himself with sports and fraternities. In 1956, he married his high school sweetheart Norma Faye Haxby. In 1957, he got his diploma, briefly hung out in Hollywood to pursue an acting career, and finally entered a Stanford University writing program led by Wallace Stegner, the legendary novelist of the American West. He took up residence at Perry Lane, Palo Alto's bohemian enclave. What happened next would be the impetus for both his novel and the fantastic episode that followed it.

In 1960, Kesey volunteered for Army-funded experiments at the Menlo Park Veteran's Hospital. It was research linked to the joint CIA-Army MK-ULTRA program, a search for truth serums and behavior-modification drugs designed for interrogations, psychological warfare and other such sinister purposes. Kesey served as a guinea pig in tests of numerous "psychotomimetic drugs"--mescaline, Ditran, LSD. He found the Ditran nightmarish (and the questioning shrinks bothersome). But he thought the LSD -- then practically unknown outside the research community -- was great. He took a job at the hospital, working graveyard shift on the psychiatric ward -- where he could dip into the chemical stash. Late-night mescaline trips on the ward gave him the inspiration for One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest.

When the book was published, the hospital was not amused. Cuckoo's Nest showed the inner workings of the psychiatric ward from the perspective of the inmates, and vindicated those who refused to knuckle under as heroes. Worse, there was a particular staffer at the hospital who recognized herself in the unflattering description of a minor character, and threatened to sue. In the second printing, the character, a Red Cross representative, was transformed into a public relations man to fudge the identity. (In the UK edition, some references to the original character were missed, and the text is inconsistent.)

Pauline Kael wrote in the New Yorker in 1975, when the movie came out, that "the novel preceded the university turmoil, Vietnam, drugs, the counterculture. Yet it contained the prophetic essence of that whole period of revolutionary politics going psychedelic, and much of what it said has entered the consciousness of many -- possibly most -- Americans."

In 1963, Kesey moved into a spacious log cabin in the redwoods at La Honda, outside Palo Alto. The following year his second novel was published, Sometimes A Great Notion -- which, like its predecessor, took its name from a line of popular folklore (in this case, the Leadbelly song "Goodnight Irene"). The book was the saga of a tough Oregon logging family in a town hard-hit by bad times and labor strife. Greeted respectably by the critics, it never achieved the success of Cuckoo's Nest. But Kesey was already losing interest in the written word, and was increasingly interested in the politics of experience.

He had started bringing drugs home from the hospital to turn on his friends, and soon the scene at La Honda outshone that at Timothy Leary's mansion in Millbrook, New York, in its fearless spirit of psychic exploration. As Tom Wolfe relates in his 1968 book of gonzo reportage on Kesey's venture, The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, La Honda was the matrix of the Merry Pranksters.

Neal Cassady, the beat legend who had been immortalized as Dean Moriarity in Jack Kerouac's On The Road, was sprung from San Quentin prison in 1960 after two years on a marijuana rap, and sought out Kesey. It was a passing of the torch from the beats to the proto-hippies. Cassady invited out his old friend Allen Ginsberg, the New York poet, Buddhist and prematurely uncloseted gay. With Kesey's pals Ken Babbs, an ex-Marine, and Hugh Romney, the core of the Pranksters was formed. Their followers donned monikers like Mountain Girl, Cool Breeze and Sensous X. Kesey became The Chief, Cassady became Speed Limit, and Romney became Wavy Gravy. To the chagrin of the neighbors, they turned La Honda into an LSD playground, with speakers aloft in the redwoods blaring Bob Dylan and the Rolling Stones. They even invited the Hell's Angles for acid parties -- a strange mix with New York intellectual Ginsberg. An odd figure called the Mad Chemist started manufacturing LSD for the project.

In 1964, Kesey purchased a 1939 International Harvester school bus, and the Pranksters painted it psychedelic. The back read: CAUTION: WEIRD LOAD. The destination sign on the front read: FURTHUR. Prankster technical whiz Tim Skully wired the vehicle with a sound system, and, with Cassady/Speed Limit at the wheel, they headed east on a cross-country odyssey that would become a prototype for a new American sub-culture. Decked out in bizarre costumes and high on acid, the Pranksters "tootled the multitudes" (as Wolfe described their ecstatic fun-poking at straight society). They were too weird even for their idols. In New York, Ginsberg and Cassady arranged a meeting with Kerouac -- but the beat legend snubbed them. They were also snubbed by Leary at Millbrook: he refused to come down from the mansion to meet them, claiming to be deep in an important psychic experiment.

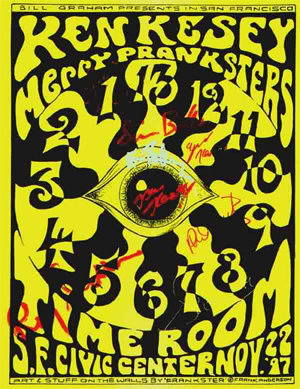

Back in California, Kesey was sought out by one Augustus Owsley Stanley III, a renegade chemistry student who offered his services, and soon became a legend for his pure industry-standard LSD-25. The Pranksters started holding "Acid Tests," inviting the public to dose on Owsley's product while Skully's wizardry with sound and light provided a mind-expanding environment. A local rock'n'roll band called the Warlocks changed their name to the Grateful Dead and provided the aural atmosphere, taking electric blues jams into outer space. The Pranksters took the show on the road, traveling the coast in the psychedelic bus, staging Acid Tests in Santa Cruz, Muir Beach, San Jose and Watts -- where the Pranksters provided garbage cans filled with spiked ("electric") Kool-Aid. "Can You Pass the Acid Test?" challenged the flyers announcing the events.

The Acid Tests culminated in a January 1966 Trips Festival -- a three-day acid party at a San Francisco hall, which energized the whole emergent youth "scene" in the city. But within days of the big event, Kesey's psychedelic career was interrupted by a pot bust.

Of course the antics at La Honda had attracted the scrutiny of the law, and police were all the more frustrated that LSD was still legal! Kesey was already looking at six months on a work farm -- and probation terms mandating breaking all contact with the Pranksters -- for an earlier pot bust at La Honda. (The cops said they caught him flushing his stash down the john; Kesey said he was painting flowers on the toilet bowl.) Now he was relaxing with Mountain Girl on the roof of Stewart Brand's house on Telegraph Hill, just nights before the festival -- when the cops arrived. When they found the stash, he grabbed it back from the officer and flung it over the ledge. This was not a brilliant move. He was charged with resisting arrest and assault on an officer as well as possession -- and was looking at serious prison time.

Out on bail, Kesey disappeared. The bus was found abandoned near Eureka with a stoned, chipper suicide note the windshield, implying he intended to hurl himself off a cliff into the Pacific Ocean. Just as the new culture the Pranksters had spawned was taking root in the run-down San Francisco neighborhood of Haight-Ashbury, and Chronicle columnist Herb Caen had coined the word "hippie" for the strange new breed of strobe-eyed post-beatniks -- the scene's progenitor had vanished, faking his own death.

It didn't take long for folks to figure out that Kesey was really on the lam in Mexico. People spotted him there, word leaked out, and the San Jose Mercury headline ran: KESEY'S CORPSE HAVING A BALL IN PUERTO VALLARTA. Fellow Pranksters started filtering down to meet up with him, and they even held a Manzanillo Acid Test, with local mariachis providing the music in lieu of the Dead. Once, when his car was stopped by police on a desert highway and pot was found yet again, he escaped by winning permission to go into the bushes along some railroad tracks to take a piss -- and grabbing onto a passing freight train. Tom Wolfe relates that he got away in a hail of bullets.

In October he returned to California, and -- still underground -- began organizing the Acid Test Graduation, a big reunion party for everyone the Pranksters had ever initiated, to be held at an abandoned San Francisco pie factory. It was time to go "beyond acid," he told his flock. "It's no longer 'Can you pass the Acid Test?,' but 'Did you pass the Acid Test?'"

Again, just days before the big event, he was busted -- recognized by police while driving on the San Francisco Freeway and chased down. His lawyers told the judge the whole point of the Acid Test Graduation was to "warn his young followers against drug use" -- which there was a grain of truth to, at least. ("You don't get anything free, everything bruises something," he told a reporter when asked if his drug experiences had come with a cost. "So you trade off.") LSD was just then becoming illegal. The judge called him a "tarnished Galahad," but Kesey was able to cut a deal: to serve the original six-month sentence on a work farm. He started doing time shortly after the Graduation.

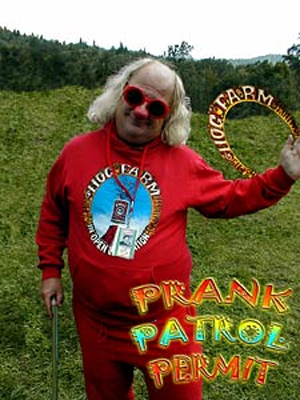

Upon his release, Kesey moved with Faye back to his father's farm in Pleasant Hill, Oregon. The media hyped the 1967 Summer of Love in Haight-Ashbury, and the Beatles appropriated the Prankster gestalt for their Magical Mystery Tour. But The Chief was going back to the land. When Wavy Gravy tried to talk him into taking the bus cross-country again for the Woodstock festival, Kesey would have nothing of it. (Wavy went out to Yasgur's farm with his own new hippie tribe, the Hog Farm.)

The movie One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest was released in 1975, and the following year won five Oscars, including best picture; best director, Milos Foreman; and best actor, Jack Nicholson. But Kesey disapproved of both Nicholson and the script, and sued the producers, eventually winning a settlement. He refused to ever watch the picture.

Although he had a daughter with Carolyn Adams/Mountain Girl -- they named her Sunshine -- Kesey's life partner remained Faye, and it was with her that he raised a family back on the Oregon farm. (Mountain Girl subsequently took up with Grateful Dead guitarist Jerry Garcia.) Ken had three children with Faye -- Shannon, Zane and Jed -- and they raised them much the way Ken himself had been raised on that same farm. In 1984, Jed, a University of Oregon wrestler, was killed when a van carrying his team to a match over icy mountain roads skidded and dropped 185 feet down a steep embankment. In an open letter to Sen. Mark Hatfield, Kesey protested that budget cut-backs had reduced the university to sending the team to matches in a borrowed van without seat belts or snow studs at the same time that Reagan was bloating the Pentagon budget. "Help deal with this, Senator. Please ... Talk about bringing some of these umpteen billions back home, back to the vulnerable guts of this nation where our dollars can actually be used for our actual national defense."

Ken's next book, Demon Box, came out in 1986, and was dedicated to Jed. It was a series of semi-autobiographical short stories with the names changed to fudge peoples' actual identities -- however slightly. Neal Cassady (who had died of exposure while counting the railroad ties between two desert towns in northern Mexico on a dare) became Houlihan. Kesey himself became Devlin Deboree.

His next novel, Sailor Song, came out in 1992. Set in an Alaska fishing village in the near future, it dealt with themes of imminent environmental apocalypse. "Critical reaction was mixed and his anti-drug critics were at their most venomous," read Kesey's obituary in the UK Guardian.

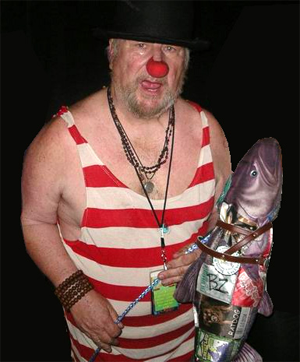

Kesey also published two books of Prankster reminiscences and memorabilia, Kesey's Garage Sale (1973) and The Further Inquiry (1990), as well as a children's book based on an Ozark folktale his grandmother used to tell him, Little Tricker the Squirrel Meets Big Double the Bear -- which was included on the 1991 Library of Congress list of suggested children's books. ("I'm up there with Dr. Seuss," he boasted.) At performances, Kesey would recite Little Tricker to orchestral accompaniment, dressed in a top hat and tails -- or with a shawl over his head, like his grandmother. For the hippie crowd, he performed with his own invention, the Thunder Machine -- a contraption devised from an old Thunderbird fender, piano strings, a smoke machine and sound-mixing gear. The thing made an awful racket, and was sometimes the opening act at Grateful Dead concerts.

His last book was 1994's Last Go Round: A Real Western, co-written with his lifelong friend Ken Babbs. This was a work of fictionalized history, about a 1911 Oregon rodeo, the Pendleton Round Up, which was distinctive for including an African American cowboy and a Nez Perce Indian among the competitors. It was based on a 1917 book chronicling the legendary rodeo, Let 'Er Buck, and was illustrated with period photos of the real-life characters -- including Buffalo Bill Cody, who makes a cameo.

On Oct. 28, 2001, Sandy Lehmann-Haupt, one of the original Pranksters and Tom Wolfe's primary source for The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test, died at his home in New York. The New York Times obituary made much of the fact that "he regretted the way Mr. Kesey and his followers had glorified drugs." Just about the same time, Kesey was undergoing surgery for liver cancer. There were complications, and on Nov. 10 he passed on at a hospital in Eugene. His own New York Times obit was written by Sandy Lehmann-Haupt's own brother, Christopher, a staffer at the paper. It revealed that nearly to his final year Kesey still took acid with some close friends for an annual Easter Sunday hike up Oregon's Mount Pisgah. "Just enough to make the leaves dapple," the obit quoted him from a recent interview.

So even after Reagan and the new War on Drugs, and the Acid Test being replaced with the Urine Test as the icon of the new orthodoxy, even after Kesey returned to his redneck roots, he remained unfashionably unrepentant.

"The first Prankster rule is that nothing lasts," Kesey told an interviewer way back in heady 1966. "And if you start there and really believe that nothing lasts, you try to achieve nothing at all times."

Well, if you're trying to achieve nothing, countered the reporter as he eyed the extravagant sound and light equipment, why do you put so much effort into achieving nothing?

Responded The Chief, in an off-the-cuff Zen koan, "We have nothing else to do."

Ken Kesey is gone, but his all-American, rough-and-ready spirit of pushing freedom to the outer limits will survive him. Because those of us who were touched by his life and works have nothing else to do.