3. Repeat After MeSAFETY I HATED -- AND ANY COURSE WITHOUT DANGER. FOR WITHIN ME WAS A FAMINE.

-- ST. AUGUSTINE, Confessions

It wasn't exactly easy getting an appointment to speak with Jetsunma privately. While her presence at the Buddhist center seemed pervasive and insistent -- perhaps the very thing, like oxygen in the air, that kept the place alive -- she was actually never around. Her days were spent mostly with her family, inside her house on temple grounds. There was an old dog. a brown Lab named Charlie, who also lived with them. There was a swimming pool, recently built. She had a Health Rider exerciser -- one of those stationary bikes with handles that pump up and down -- which she enjoyed riding. But what she did, aside from praying and eating meals and working out on her Health Rider, intrigued me, and haunted me. How does a living Buddha pass the time? I had been told she liked watching Absolutely Fabulous and Star Trek: The Next Generation on television. She liked listening to Motown oldies. I had heard she often shopped for clothes by mail order. She had two attendants and a private secretary, Alana and Atara and Ariana, all ordained nuns, who kept her life organized. They opened and answered Jetsunma's mail, made sure her house was clean. helped take care of her eight-year-old daughter. Atira, grocery-shopped, and looked after the cooking of the family's dinners.

Presumably it was through these attendants that word of Jetsunma's daily life would occasionally leak out. I'd hear, secondhand or thirdhand, that Jetsunma had enjoyed a certain movie she'd rented (usually sci-fi or adventure tales) or was interested in a certain book (a self-help classic, Radical Honesty, was a favorite for a while, and Gail Sheehy's book on menopause). Sometimes I'd hear she was excited by the appearance of a particular new student, or by someone asking to become ordained. Sometimes she'd be craving a certain kind of food, or go on a special diet. Her students would get wind of her new passions -- and suddenly there would be a slew of them trying out her diet or buying Health Riders. KPC was its own enchanted world, with its own news bulletins and trends, its own royalty. It was as if a long invisible wall traced the boundaries of the Tibetan Buddhist center, keeping its spell intact, and within that wall was another wall protecting Jetsunma herself. She seemed to live not simply yards away from the front door to her temple but worlds beyond.

When I'd first met Jetsunma a couple years before, she hadn't seemed so remote or exalted. Our interview felt relaxed -- and was in an informal temple sitting room upstairs. She was jolly, easygoing, and I liked her immediately. I felt completely comfortable around her. The only thing that puzzled me was how Wib seemed to throw himself on the floor when he entered the sitting room where Jetsunma was waiting for us, and how he prostrated three times.

She had little in common with me in terms of lifestyle or background -- except that we were both half Italian -- but there was, nonetheless, the feeling of a bond or connection between us, a kind of mutual understanding. After my article was published I remained fascinated with Poolesville -- and with Jetsunma. I had the nagging sense that there was more to know, and more to write. She came into my mind at the oddest moments -- on bumpy airplane flights and when I was writing on deadline. She had even appeared in my dreams. I had learned that my father was dying, and part of me felt vaguely comforted by the idea of her, of a woman familiar with magic and miracles, and one who seemed to know the human heart. It was as though I carried around a piece of her -- the sound of her voice, a sense of her, a spirit or presence -- that I couldn't shake.

In Poolesville, Wib was my go-between, my conduit to her in those days. Jetsunma's telephone number was unlisted and kept private, even from most of her students. "Otherwise, I'd get calls all day," she explained later, "people asking me which cereal to buy." If I had a question, or hoped to set up a meeting with the lama, I had to call Wib at home -- sometimes getting Jane or one of their young daughters on the line first. Wib was always kind and welcoming, always sounded happy to hear from me, but as time passed and my suggestions for meetings were sometimes left hanging for days, weeks, it became obvious to me that "getting to know" a Buddhist lama was a curious and perhaps absurd ambition. Even the experience of covering Hillary Clinton during her reclusive first year in the White House hadn't prepared me for the perplexing process of writing about Jetsunma Ahkon Lhamo. And just as I began to fantasize about giving up, I'd get a call from Wib out of the blue. "Jetsunma thinks the name Random House sounds very good," he'd say, after I'd told him the publisher of my book about KPC. Or "Jetsunma feels very good about this project and seems very excited." One time, in passing, he asked for my new boyfriend's full name -- something Jetsunma had inquired about.

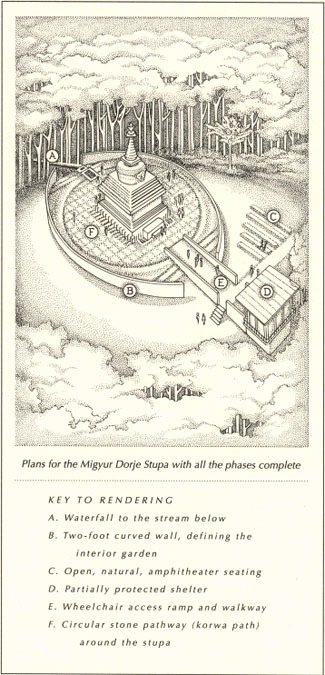

As I waited to see her in October and grew increasingly anxious, I checked on the progress of the stupa, interviewed the visiting Stupa Man, and studied the relics in the prayer room. I sat with David Somerville in his construction trailer on the stupa site. I went to see Doug Sims at his home (his Health Rider was prominently placed in the living room). I tried to get in touch with Sangye and learned that he was recuperating in a cottage on the temple grounds, being nursed by a team of nuns. I began my inquiries into Jetsunma's life story and spoke with Shelly Sims and Jon Randolph and Eleanor Rowe, three of her oldest students. And as the weeks passed and my frustration grew, I learned a valuable Buddhist lesson: If I wanted to remain calm and sane, I shouldn't count on seeing the lama at all.

Each visit to Poolesville provided new tidbits of information, though, adding to what I already knew about the temple and its beginnings. Jetsunma's story grew like a vine, too, and the longer it became -- the more it twisted and curled in on itself -- the more it drew me. Quintessentially American stories are usually material success stories -- a class nerd becomes a billionaire, an awkward girl becomes a movie star. Or they are stories of a political rise: a poor man becomes a senator or congressman or the president of the United States. The landscape is crowded with such legends. But each time I learned new things about Jetsunma's story, the more magnificent it seemed. It had a stunning arc, such a Star Is Born quality that it was strange it wasn't Hollywood that had found her, created her, lifted her out of obscurity and squalor, but a holy man from Tibet who walked with a limp, couldn't speak English, and knew very little about the West.

***

She was born Alyce Louise Zeoli, on October 12, 1949, a calm, bright, and imaginative girl -- a quarter Dutch, a quarter Jewish, and half Italian -- who seemed to thrive and do well in school despite the atmosphere at home. Her mother, Geraldine, was a tall woman, dark haired, with large blue eyes and a prominent nose, something of a beauty in her youth. But she was a single mother who struggled to make money, working in factories and as a grocery store cashier. As a young girl Alyce was often left with her mother's mother, Alyce Schwartz, for whom she'd been named. Her grandmother could be supportive at times and act like the sweetest friend. Other times she turned cold and bitter. "Look how much you're eating! Look how much. What's wrong with you?" She also showed signs of mental instability. She was playing cards on the floor of the living room one night when she looked up from her hand and suddenly didn't recognize her own family. Another time Geraldine came home early from work and found little Alyce sitting on the stoop in the snow. She wasn't wearing a coat or underpants, only a dress. Her grandmother had put her outside, locked the door, and forgotten about her.

Alyce's father was Harry Zeoli. Her mother claimed to have married him when she was twenty-two and had the marriage annulled soon after -- when Zeoli was arrested for stealing a car. The man who was largely responsible for raising Alyce was Vito Cassara, a truck driver and fix-it man who married Geraldine when Alyce was two. Vito always had a great deal of trouble fInding work, but he was able to move his new family into a small brick walk-up on Ninety-eighth Street in the Canarsie neighborhood of Brooklyn, just around the corner from the Bay View housing project. He and Geraldine began having children. As Jetsunma remembers it, her mother felt best when she had a baby in the house. "If she didn't have a baby, she'd start another," she said. "It was really like that." When Alyce was three her half brother Frankie came along; he would remain close to her throughout their youth and early adulthood. Three more children followed, and Alyce was left to raise herself and look after them.

When Jetsunma remembers Vito Cassara, she mostly remembers how the electricity and gas were always being shut off in the Brooklyn house, and how Vito taught the kids to hide from bill collectors. She remembers his big fleshy nose and red face. She remembers the hollering, and the way a handprint could swell under her skin after she'd been slapped. She remembers how a bruise was blue and spongy before it became green and yellow. She and her younger brothers never could recall what they'd done to deserve punishment. Vito drank when he was worried about money.

Vito threw an ax at Frankie once, and another time Jetsunma says she watched her stepfather beat Frankie with a saw. She watched the imprint of the saw's teeth marks rise on Frankie's legs. He was five when Vito knocked him to the floor and kicked him in the head so many times that his eyes crossed and he had to be taken to the emergency room. Geraldine said he had fallen down a flight of stairs, but the doctors pressed her, trying to get her to admit that her husband had done it. She wouldn't. "She protected him," Jetsunma would say years later. "That's the one thing I hold against her the most."

Alyce liked to comfort Frankie and reassure him. Someday things will be different, she'd say. Someday, she'd say, we'll buy a big white house in the woods, and it will be beautiful and perfect and safe.

She fantasized about her real father, too. She imagined Harry Zeoli ringing the doorbell on Ninety-eighth Street. She imagined him discovering how her life was and taking her away from Brooklyn, from the violence and ugliness, from the small house crowded with her half siblings and Vito and Geraldine and her crazy grandmother. "I used to ask my mother about my real father, and she would always paint him to be a terrible person. But I never believed it," she said. "I held out. To me, my father was a good father .... In fact, when I used to watch the show Ben Casey on TV, the star of the show was named Vince Edwards, but I learned somehow that his real name was Vincent Deoli, [1] and I had a fantasy for a while that he was my father and he'd changed that one letter of his last name, from a Z to a D, and that he was a great guy. I even imagined that he was really a doctor, too, and he'd come and save my life."

The family moved to Miami when Alyce was fourteen so that Vito could find work more easily; eventually he opened his own locksmith business. And it was there, in the sunny suburb of Hialeah, that Alyce discovered that other families weren't like hers. "I noticed that other people actually talked to each other without screaming," Jetsunma said. "And other families never beat each other. It was a huge awakening for me, and a tremendous relief. It meant there might be something else out there. Some other way of living for me."

In Hialeah she made friends easily and attracted strangers. . . . She had what the Tibetans would later call ziji, charisma, and a certain kind of energy that made people want to stare at her and spend time in her company. She did impressions, cracked hilarious jokes. Her face was pretty. Her voice was husky and kind. Her body was plump and maternal. Her goodwill was infectious. And her ability to connect was dazzling. Impatient for her new life to begin, she started pursuing boys. They tended to be druggies and dropouts -- "inappropriate guys who generally weren't up to my speed," Jetsunma said. At sixteen she started craving independence. She bought a car and got a part-time job with the phone company. She began her first serious relationship with a boy. The the law there had been changed -- you had to be eighteen to marry. Alyce and her boyfriend decided to lie to their parents and claim they'd gotten married anyway. They talked about having a baby soon, too, to ensure that they be allowed to stay together.

Alyce called her mother from a pay phone in Georgia, but she found herself unable to lie. "Something she said made me trust her," Jetsunma said, "and something in her voice had made me homesick and start crying." At her mother's urging Alyce told her where she was -- and within minutes Vito had called the Georgia State Troopers. "You better get to my daughter before I do," he told the police, "because I'm going to kill her."

Back in Hialeah and forbidden to see her boyfriend, Alyce retreated to her room, and a weird detachment crept over her. She felt removed from herself, then removed from her body -- as if she were across the bedroom and watching herself fall apart. "It must have been near the holidays, because I had this Christmas corsage," she said, "and I remember picking this corsage up and that it suddenly wasn't a corsage anymore but my doll Mickey that I had when I was a little girl. It was a doll I had before my mother and my stepfather had gotten together. So I was holding this corsage in my arms and I was singing to it, singing to Mickey, and I was holding Mickey. And then I began throwing Mickey against the door, and pieces were falling off.

"My mother must have heard the sound of the knocking in my room, because she came in. She told me later that I was talking like a little girl, baby talk, saying words I used to say when I was little. And I told her, 'Mommy, Mommy, Mickey is broken. I don't know how to fix him. I don't know how to fix Mickey.'"

Jetsunma believes she had a "kind of breakdown," but it felt planned, like a lucid decision to lose control. The whole thing felt "contrived" and "totally honest" at the same time, she said. "Both sane and insane."

Her mother, oddly, seemed to know exactly what to do. "She became very strong and clear," Jetsunma said. "She walked me around the house and started talking to me very softly and made me warm milk. She made me feel safer. And then she put me to bed, tucking me inside the sheets like I was a baby."

The next morning Geraldine called Hialeah High School and asked whether she should send her daughter to classes or not. Alyce was acting very strange. Was there a school psychologist her daughter could see? "I wasn't acting like a baby anymore, but I was definitely still out of it," Jetsunma said. "Like I was directing myself in a movie."

A school counselor evaluated Alyce and sent her to the offices of Dr. Ronald Shellow, a psychiatrist who specialized in adolescent illness and juvenile delinquency. She began therapy with him that would last nearly three years and was paid for by the state vocational rehabilitation program. "I made some slow progress," she said, "but I don't remember very much of the following year -- the year I turned eighteen. Apparently I had some rather big adventures. Later on, guys would come up to me and say, 'Hey, that was a great time we had!' and I had no idea what they were talking about."

Dr. Shellow helped Alyce make the decision to move out of her parents' house and continue school and her part-time job. She began doing her own cooking, learned how to live paycheck to paycheck. She broke up with her boyfriend but always found a new one. "I had to have a boyfriend," she said. "It gave me a sense of security, I think, and the illusion of support. Thinking back on it, I have the image of two puppies in a box. It's a comfort to them -- but are they really involved in caring for each other?"

More than any boyfriend it was Dr. Shellow who got her through those years. He believed in her, made her feel good. After a certain amount of time in individual analysis, he encouraged Alyce to join a therapy group he was running. In an interview Dr. Shellow -- who was given permission to discuss his treatment of Alyce -- remembered her as "overweight" but "an attractive girl who took care of herself." She tended to be hysterical rather than depressive. She had sexually provocative fantasies. She told the truth. She was concerned about being "a good girl." She wrote poetry that worried her high school teachers. Her boyfriend was a loser, her stepfather was a drunk, and her mother "had her own problems -- mostly with her husband."

But it was Alyce's dreams that Dr. Shellow remembered most. They were "very interesting dreams," he said. She was pregnant in most of them. And the recurring theme was that she was in the hospital, giving birth. The baby was beautiful but also "had something wrong with it." Sometimes the baby had crossed eyes or funny hair. And Alyce felt tremendous love for the baby. But in the dreams, rather than taking the baby home and keeping it for herself, she planned to give the baby to her mother -- as a way finally to make her happy. "I've never had another patient give me a dream like that," said Dr. Shellow, "this fantasy of giving birth to something wonderful and it being for somebody else."

In his therapy group Alyce talked easily and candidly about her feelings; she was never withdrawn or seemed uncomfortable. She was adept at dispensing advice and quickly became involved in helping her group mates. Eventually she became more interested in helping them than in talking about herself -- although it probably needs to be said that this stance allowed her to remain in control and be the center of focus. "She was always jumping in," said Dr. Shellow, "solving problems, making comments, interpreting everybody else's dreams ... often before I had the chance to come in and say something. Essentially, she led the group. And it was always very interesting."

***

With each passing year the world of Alyce's childhood -- the bleakness, the impotency and despair -- grew fainter and fainter. By the time she was an adult, the house on Ninety-eighth Street in Canarsie literally didn't exist; it had been torn down and another small brick house built on the lot. Her mother divorced Vito Cassara, and he disappeared into legend; Alyce came to believe, or hope, or dream, that he had been sent to jail. Her real father, Harry Zeoli, would never emerge as the star of Ben Casey, or turn up at her door.

She moved on and stumbled upon compensations. When she was nineteen she married Jim Perry, a boyfriend from Miami. They had a baby named Ben. Opportunities to go to college never came, but she took night courses and worked as a day-care assistant and as a nanny. She got jobs in retail stores and sold clothes. After she and Perry were divorced, she moved to Asheville, North Carolina, with another boyfriend, a radiologist named Pat Mulloy.

During these years, as her own life began taking root, Alyce's contact with her old family -- Geraldine and Frankie and the rest -- was sporadic and difficult. They barely spoke. Alyce would sometimes find herself missing them. She'd call up and arrange a reunion. Her yearning never ceased -- for a mother, for a real father, for brothers and sisters to love. She'd find herself believing again that repairs were possible, that intentions had been good, that the mistakes were forgivable, and that people could change. So periodically Alyce would find herself sitting around with her mother and half siblings, whose lives were now tortured by their own demons. During these reunions the boys would open their shirts and show the scars. Alyce would tell dark jokes, her rage funneled into disgust and vulgarity. Geraldine would smoke cigarette after cigarette, always remaining silent.

Following such an evening Alyce would feel exhausted, then overcome. She'd go to bed and cry for hours. "Tell me I'm not like them," she'd say to her husband. "Please, please, please. Tell me I'm not."

***

In Asheville she lived on the fringes of town. There were dilapidated shacks and trailers nearby and, sprinkled among them, a few nice houses that looked cared for. Alyce's small farmhouse was one of those. She owned a cow, grew her own vegetables, stoked the woodstove in the winter, and lived a relatively quiet life. After several years together she and Mulloy had a son, Christopher, and were married.

She was a housewife and a mother. There were meals to cook, groceries to shop for, dirty clothes to wash, an ordinary life. Yet, as the months, and indeed the years, passed, the more ordinary her life became, the more restless Alyce grew. It was "a profound restlessness that wasn't entirely conscious," she recalled. And by the time she was in her mid- to late twenties, "it was powerful, a dynamic force from way inside me." She had always been sedentary by nature, a bit lazy -- and in recent years she had become quite overweight. Suddenly, though, she felt energized. She felt propelled toward something. But what?

The force felt magical, and she turned to magic for answers. A fortune-teller told her she was psychic; an astrologer told her she was important. An old tarot card reader on Coney Island told her she was originally Tibetan. Her dreams became powerful. Once asleep she was welcomed into a strange and elegant wonderland. She walked into mystical palaces and met half-human creatures. Again and again she was told she was special, she was different, she was gifted and full of wisdom and insights. Soon she began wanting to be asleep more than she wanted to be awake.

She started to meditate -- as a way to enter a dream state without sleeping. She taught herself, made up things as she went along. She didn't learn until much later from the Tibetans that you are supposed to sit, not lie down. You are supposed to keep your eyes open, not shut them. At first it was just an hour a day. She would slow down, sink into a different state of consciousness. Her meditations were not simply exercises in relaxation, or strings of sounds, a mantra, repeated over and over. She preferred to be praying, and her meditations became little plays she would run inside her mind, visualizations -- in which she made wishes and offerings to God. She was fascinated by the mechanics of praying, and by an ambition to devise more efficient and powerful forms of prayer. It became almost a game. On her bed in the afternoons, she imagined she was offering up parts of her body to God. First she'd offer her toes and her feet to God. The next day she would offer her knees, her legs, her hips ... She spent hours contemplating the various parts of her body and appreciating them -- how well her feet worked, how they helped her stand and walk. She thought about how attached she was to her body -- how much she loved her feet, and how life would be without them. And with this in mind she would offer them, imagine cutting them off and giving them to God. Years later she'd be told this is an advanced Tibetan Buddhist practice called Chod.

She would give anything to God, she thought, anything, if her gift might help the world become settled, happier. The deeper she went -- the closer she came to the kingdom of her dreams -- the closer she felt to her true self. Sunk into a trance, she always prayed for the same thing: "Make me a channel of blessings." There were hours of this, days of this, weeks of this, months of this. "Make me a channel of blessings, make me a channel of blessings ... " The prayer became a part of her breath, a part of her consciousness. After a time she felt herself changing, as though the prayer had transformed her. Suddenly it was as if she were a faucet, and the blessings were running out of her like water, and all she had to do was turn on the tap.

She prayed for peace. She prayed for the world. She prayed for an end to suffering. She prayed for purity, for light, for clarity, for answers.

The conclusions she reached stayed with her: We have all lived before, many lifetimes -- and on other planets and lost continents. Our past actions are responsible for the lives we are having now. All souls are connected, in some silent, mysterious way, through their hearts. And there isn't a God so much as a universal spirit, a primordial feeling, an energy and wisdom that is formless. It is the true nature of all things and inseparable from us.

***

Going to church had never much interested Alyce. She'd been baptized in the Roman Catholic Church and had often attended Dutch Reformed services with her grandmother. And while the family considered themselves Jewish, too, the only Jewish thing they did was eat bagels. But it really wasn't the religious ambivalence of her childhood that had turned Alyce off. The truth was, church seemed fake to her -- rigid and shallow. She imagined if she talked about her heartfelt experiences with prayer, she might be ridiculed. Eventually, she and Pat Mulloy found a home at the Light Center -- a nondenominational group that met in Black Mountain, just outside Asheville. It wasn't very organized and didn't seem much like religion. It was simply a place where the divine mysteries of life were celebrated, and where serious scientific discoveries were discussed in the same breath as outrageous New Age theories. The students were instructed to pray for the planet, for world peace, for enlightenment, to end hunger, and not for themselves. Alyce was able to talk openly about her dreams and meditations, and some of the answers she'd found. She found sympathetic listeners -- people who sat down beside her, enthralled. "I was instantly a joiner," Jetsunma said of the Light Center. "And I really got mixed up with that group and was really happy to be there."

Jim Gore, who ran the center, was a lecturer and psychic who became Alyce's first spiritual mentor. He taught various meditations and practices, but the mainstay at his center was a prayer called the Light Prayer. You imagined yourself as a body of light, then visualized that light going out into the world. After attending several of his lectures, Alyce approached Gore to tell him about a dream she'd had: She was walking outside when the sky opened up over her head. A dove came down and began to circle her head. A voice said, "You are the light of the world ... this is who you are."

Gore smiled and took Alyce's arm. "I'll tell you something I know about you," he said. "You're not like other people. You're different. Did you know that about yourself?"

***

In her early years at the Light Center, Alyce was encouraged by Jim Gore. He felt she was a visionary, and extraordinarily psychic. On a few occasions he referred to her as a superbeing -- the greatest compliment he could offer. He often singled her out in classes and called on her to speak to the group. After a short time she was teaching meditation and giving private psychic readings -- very much at Gore's prodding. He lauded her intuition and accurate predictions, as well as her courage to cut the niceties and head straight for the core.

Late in 1980 she gave a psychic reading to Michael Burroughs, a graduate student in religious studies at the University of Virginia who was visiting friends in Black Mountain. ''I'd heard all about him before I'd met him," Jetsunma would recount later. "People were always saying, 'You gotta meet Michael Burroughs. You gotta meet him.'" He was a southerner with a slow Tennessee drawl and at twenty-five -- four years younger than Alyce -- seemed charming and wise beyond his years. Like Alyce, Michael had a quick mind, a mystical bent, and a rather dark sense of humor. But unlike Alyce he was well educated and accomplished -- he was finishing work on his second master's degree, and made a living as a church organist and a regional lecturer of Transcendental Meditation. Alyce was still working in the day-care center, and the thought of supporting herself as a spiritual teacher seemed a remote possibility.

"Do you have a girlfriend?" she asked Michael, during his first reading.

"Not really," he said.

"Well, you are about to be involved in a terrific relationship," she said. "Boy, I wish I were going to have a relationship like that -- and the woman's name is Catharine."

Michael started coming more often to Black Mountain. He encouraged Alyce, came up with ideas for how she might support herself as a teacher, suggesting she begin offering workshops and seminars. Quickly becoming close friends, they gossiped about other students they knew and about Jim Gore's recent teachings. Alyce liked the way Michael ridiculed some of the New Age practices at the Light Center -- so when Gore began encouraging her to try channeling, she wanted to know what Michael thought. Alyce had tried it privately but felt embarrassed and unsure about channeling in public. When Michael visited Asheville again, would he help her?

Over the summer Alyce confided in Michael that she was considering leaving Asheville -- and had dreams of starting her own prayer center. "We were both growing a little critical of the goings- on at Black Mountain," she said. "It was getting too psychic phenomena-oriented and flaky. It became too much about aura cleansing and trying to project your consciousness to different places. None of which does the world much good at all. Michael and I thought of ourselves as much more serious."

Jim Gore had also become a bit overbearing. Alyce had started to attract attention with her psychic readings -- people were coming to her now, wanting help with their meditation techniques -- and Gore had begun ignoring her. "He told me I was a superbeing," she says, "and eventually didn't have anything to do with me." Unlike the students who were made insecure by this kind of treatment and drawn further into Gore's influence, Alyce saw through it and quietly made plans to depart.

She and Michael talked long into the night during this time about what the ideal spiritual center would be like. Alyce had grown to believe that the New Age feel-good talk was vapid, overly upbeat, and that studying psychic phenomena -- although fun and entertaining -- was a waste of time. People should be taught to search themselves in a deeper way, to face their intentions, to deal with their demons and commit themselves to a practice of prayer that would build compassion. Alyce felt a sense of mission and a calling as a teacher, a muse, a spiritual instigator. She had already seen how she was able to attract people to begin an examination of their lives. Michael. having been raised in the Baptist Church, understood the need for structure, rules, a sense of hierarchy and order. Together they agreed that the perfect spiritual center would be nondenominational but teach the general guidelines and scriptures that all religions hold in common. And it would emphasize "active prayer" above all else. Prayer was real, and worked. It was an acknowledgment of the oneness of all things and showed devotion to that universal spirit, to the essential nature that all things share.

It came as a shock to the students at the Light Center when Alyce announced, later in 1981. that she and Pat Mulloy were separating. The perception was that Alyce and Pat were a supportive and spiritual family -- Jim Gore had called them the "First Christed family" -- and meant to be together. Since they'd become close friends Michael had known that Alyce was unhappy and wasn't surprised by the news that she wanted to leave Mulloy. But what came next did surprise him. Not long after her separation Alyce confessed to Michael that she believed the two of them were destined to be together. In a channeling session she told him that they'd been together in many previous lifetimes -- often as rulers of galaxies and unrecorded ancient civilizations on earth. Over the summer, as they grew closer, Alyce embarked on a serious diet, and by Christmastime she had dropped one hundred pounds.

Eventually Michael came to feel it was true. He and Alyce had something special together. There really wasn't anybody like Alyce ... the way she made friends instantly, how funny she was, how warm, how smart. Her spiritual capabilities seemed endless to him, and her talent for teaching -- once she'd made up her mind that she wanted to have students of her own -- was incomparable. Michael even believed some of the past-life stories Alyce had told him. Why not? Who's to say those things couldn't have happened? Above all, Michael felt very strongly that her intentions were pure. She wasn't one of these self-involved flakes who populated the landscape. She believed deeply that her mission was to help people and make the world a better place. Over time he found himself unable to imagine life without her.

By the following winter they were a couple. Michael moved to Washington, D.C., to study comparative religion at American University -- for his third master's degree -- and Alyce drove up on weekends. To help make ends meet, and in hopes of attracting some students, Michael made arrangements for Alyce to speak informally at spiritual centers and to New Age groups. Through these events they were quickly able to find kindred spirits, even in a place as buttoned up as Washington. "They came to dinner at a group house I was living in," remembered Wib Middleton, "and she channeled afterward, which really blew us all away. And I remember when we were alone, she looked at me and said, 'I've been meeting lots of old friends lately.' And I felt I knew what she meant. We had a strong connection."

To mark her new life, she decided that she didn't want to be called Alyce anymore. She didn't feel like Alyce. She didn't even look like Alyce. She decided to start calling herself Catharine.

***

She got a job at Paul Harris in Mazza Galerie for a time, selling men's clothes, and Michael was playing the organ at various churches. They quickly made new friends, mostly through a network of former Light Center students living in the Washington area. Through a friend of a friend they met Eleanor Rowe, a refined intellectual -- a former Russian literature professor at George Washington University -- who had a fascination for metaphysics. Eleanor became a patron of sorts, a sponsor and supporter of Catharine. She hired Catharine to work as her nanny, to house-sit while she traveled over the summer. And later, convinced of Catharine's abilities as a channeler and psychic, she consulted her about a string of physical ailments that had been plaguing her. "She was a tremendously gifted healer," Eleanor said. "And I'd tried everything -- acupuncturists, priests, a shaman, various yogis. I knew all kinds of big-name gurus, including Swami Muktananda. But only Catharine was able to diagnose the problem, and then fix it."

Michael played the organ at the Church of Two Worlds in Georgetown, a spiritualist congregation. He and Catharine were married there in 1983 by Rev. Reed Brown -- who later ordained them at the Arlington Metaphysical Chapel as "metaphysical ministers" in his spiritual church. But Catharine worked better on her own, so Eleanor offered her house as a place where groups could gather informally for her teachings. Eleanor also began recommending Catharine's psychic consultations to friends and acquaintances. Sylvia Rivchun came for a session. Jane Perini and Shelly Nemerovsky came, too. These were something like conventional psychic readings except that it was difficult to keep Catharine interested in the mundane -- and questions about jobs and houses and marriages sometimes went unanswered. She was mostly interested in a person's spiritual path, and the extent to which a person was living consciously, being ruthlessly honest, and practicing compassion. Often she would recommend meditation to a client and suggest a few techniques of her own.

You have lived many lifetimes, Catharine told people, many, many lifetimes. Look into the night sky, look up at all the stars, the millions of stars. We have all lived as many lifetimes, and we've come from places as far away.

Catharine and Michael moved into an apartment in Silver Spring -- a place large enough to hold her classes in the living room. Twenty or thirty regulars sat on the floor and listened to Catharine's teachings every week. They called themselves the Center for Discovery and New Life, and within a year membership had doubled and then tripled. To accommodate the expansion Catharine and Michael moved into a one-story brick rambler in Kensington. It was a nice neighborhood of Maryland, close to Rock Creek Park, but the main feature of the Kensington house was the big basement, with its knotty pine paneling. It was an ideal place for the group to hold weekly meetings -- and for Catharine to give her psychic readings more privately than in the family living room. There was a small bedroom next to the paneled basement, too, which Michael used as an office.

It was Michael's ambitions for the center, and his public relations skills, that often drew newcomers to the classes. He had even begun to arrange out-of-town speaking engagements for himself and Catharine -- and they'd attracted a group of students in Lansing, Michigan. But it was Catharine's talent for teaching and connecting to students on an emotional and nonintellectual level that kept them there. At a distance they seemed like an odd couple, Catharine and Michael. They had been married less than a year. He was of medium height and slight build -- weighing no more than one hundred and forty pounds. She was large framed, fairly tall, and had thirty or forty pounds on him. While she had a bawdy sense of humor and a deadpan delivery, by nature Catharine was a homebody and not entirely comfortable meeting people. Michael was more reserved on the surface. He was erudite, an academic -- a person, it seemed to some, who was all brain and little heart. But he was also a natural at administration, at filling out the proper forms for tax exemption and coming up with ways the group could expand its reach.

The early students would later be regarded as very special and referred to as the First Wave. In their most heady moments they thought of themselves as something like the twelve apostles. "We were kind of a ragtag group," said Wib, "but we felt like an intimate family and like what we were doing was important." They were Wib Middleton, Eleanor Rowe, Shelly Nemerovsky, Sylvia Rivchun, and Jane Perini. There was a software engineer named David Somerville. There was Don Allen, an administrator at the U.S. Postal Service, who fIrst came to the Kensington house in 1982 and introduced his son, Jay, to the-center by giving him a private consultation with Catharine for his nineteenth birthday. Jay dropped out of James Madison University after his freshman year because he didn't want to miss Catharine's weekly teachings. "I had found the thing I was looking for and the thing that was making my life meaningful," he would recount later. "I had to pursue it."

Janice Newmark came to Catharine for a private consultation, admitted she was suicidal, and began attending classes -- reinvigorated about her life. Tom Barry was a Washington-area businessman with Pentagon contacts when he first came to a class in 1983 and had a four-hour consultation with Catharine, asking her if it was possible to attain enlightenment and be an arms dealer at the same time. "The divine can do anything," Catharine told him, "but why push it?"

Karen Williams began coming regularly -- she was a sound technician at NBC, a cheerful and wry-humored ex-flower child from Berkeley -- and sometimes brought her NBC colleagues. Christine Cervenka was a beautiful twenty-four-year-old blonde from New Jersey who had given up on the Catholic Church -- and Catharine told her she'd had a dream that she was coming. Ted and Linda Kurkowski -- he was a solar energy expert, she was a management consultant -- had come for private consultations with Catharine and stayed. Elizabeth Elgin was an insurance secretary when she first met Catharine, and also never looked back. The students in Michigan had become organized and devout, too -- Catharine flew in once a month to teach there. Another far-flung student, a recently divorced businessman from Florida who had met Catharine in Asheville, moved to the Washington area when he learned she'd started her own center. His name was Jon Randolph. Catharine told him he'd been her student before -- in ancient Egypt.

She and Michael described their center as nondenominational, but many of the members -- like Wib Middleton and Jay Allen -- considered themselves "metaphysical" Christians who were being taken by Catharine to a new level of spiritual understanding. Others simply felt they were studying a kind of Western mysticism. Still others just came for the wild talk of past lives and UFO's. "The man at NBC who originally introduced me to Catharine," said Karen Williams, "stopped coming to classes after the first year or so, when he figured out it was more about prayer than intergalactic travel. That's all he ever wanted, really -- to be taken up in a spaceship-and somehow he thought Catharine could make that happen."

"She talked about the absolute nature of all things, and the focus was always the power of prayer and benefiting others," said Wib. "Her voice, and the way she said things, made sense to me. We were all looking for something to sink our teeth into -- and she was talking about compassion and not self. At that time what was out there, in the spiritual marketplace, was very self-absorbed, about healing the self.... I'd done est weekends, among other things, but what really struck me -- and many of us -- was here was somebody who wasn't talking about self-improvement or psychic development."

Quite naturally, and also at Catharine's encouragement, students began to hook up romantically. Wib Middleton began dating Jane Perini in late 1983, Don Allen hooked up with Shelly Nemerovsky, and David Somerville fell in love with Sylvia Rivchun. "When the group would meditate together," David remembered, "I would close my eyes and become sure that Sylvia was staring at me. I could feel her, staring at me. And then I'd look up, and she'd just be sitting there, meditating. And her eyes were shut."

Catharine delivered her teachings in a trance state. She sat in a green velour chair, closed her eyes, and spoke in the voice of a man who called himself Jeremiah. The voice taught about the indivisible union of all things, about the emptiness of the physical world, about stewardship and caretaking of the earth and all the creatures on it. The voice was against abortion. It loved Jesus Christ. The voice was always encouraging the audience to act ethically and consciously and compassionately in the world.

Sometime in 1984 the teachings became increasingly Eastern and esoteric. Michael himself had gotten interested in Buddhism and had purchased some books on the subject. Catharine disliked taking a scholarly approach to spirituality, but she was drawn to what Michael told her about Buddhism. "He'd read something to me," she'd say later, "and I'd feel I knew what was being talked about." She quickly put the concepts into her own words. She wrote a vow that she asked her students to take, not unlike the Bodhisattva vow, which Tibetan Buddhists take, dedicating themselves to helping the world. She talked about "voidness" and "oneness" and the indivisibility of all things -- and gave a teaching called "no-thingness" -- which made the Buddhist concepts of emptiness and nonduality easily accessible to her students. That year, when she and Michael bought a new car, a blue Renault Alliance, they ordered a vanity license plate: OM AH HUM," the words for "body, speech, mind," and a Buddhist prayer.

Catharine talked about karma, too. She told her students that the United States had a "karmic pattern of compassion" that began with the founding fathers -- and that Thomas Jefferson was a "wisdom being." If one was born in the United States, that compassion was one's legacy. There were prayer vigils at the Jefferson Memorial on several occasions after Catharine predicted that a tragedy was about to take place -- a political figure was about to be assassinated or a negative entity in outer space was heading toward the earth in a spaceship. The group often prayed all night -- and they were thrilled by their success at keeping negativity at bay. "Catharine would always proclaim afterward," said Karen Williams, "that we'd accomplished some miraculous thing."

Catharine had taught them a form of meditation called the Light Expansion Prayer, a variation of Jim Gore's prayer in Asheville. Eventually the group began a round-the-clock prayer vigil in the basement of the Kensington house -- a prayer for peace, for harmony. The students came and went at all hours, praying for peace in two- to four-hour shifts.

***

In the fall of 1984, Catharine's prayer group was introduced to a man named Kunzang Lama, who represented a large monastery in south India. He was raising money for Tibetan refugees. Did the Center for Discovery and New Life wish to sponsor young monks in need of books and clothing and proper food? Kunzang Lama arrived at the Kensington house one rainy night with a carload of Tibetan rugs to sell and photographs of beautiful Tibetan boys in robes. Catharine's students were soon sponsoring twenty little monks, then fifty, then seventy. The rugs sold quickly.

Several months later Kunzang Lama contacted them again. The head of his monastery, Penor Rinpoche, was making his first trip to the United States. Kunsang Lama asked if their group could find a place for the rinpoche to stay. Catharine and Michael offered their house--and they organized a dinner for the lama and arranged two speaking engagements for him in suburban Maryland. Despite a burgeoning interest in Eastern religion, Michael seemed to think that Rinpoche was his last name. "I didn't really know what a Buddhist was, much less a lama," Catharine would say a few years later, when the reporters came, and the magazine writers, and the TV crews. "And when I imagined Tibet, my first thought was of old men and smelly rugs."

Their first inkling of Penor Rinpoche's status came when Michael and Catharine arrived at the airport to meet his plane, thinking they would be the only ones there. Instead, they found a hundred or so well-dressed Chinese swarming Penor Rinpoche's gate, holding white scarves and bouquets of flowers. Michael and Catharine looked at each other. Who could have known? They couldn't really see the lama as he emerged from the Jetway, but a sea of dark heads in front of them began bowing, then prostrating. Hands were reaching out to him, with offerings and scarves for the rinpoche to bless and return.

Catharine would later describe the moment she first laid eyes on His Holiness Drubwang Pema Norbu (Penor) Rinpoche, the eleventh throne holder of the Palyul tradition in the Nyingma lineage, as a miraculous and stunning awakening. She would tell the story many times, and on each occasion the description seemed to become more wondrous and fateful. "It was like a shampoo commercial," she liked to say. "I looked over the crowds of people and suddenly caught sight of His Holiness." He was a short and stout figure, wearing burgundy robes and heavy eyeglasses, and limping faintly as he passed the hoards of welcomers. As his face looked up into hers, Catharine says she broke down sobbing. "I felt," she says, "like I was meeting my mind."

A few hours later, after a lunch in downtown D.C. and a couple of prearranged stops and appointments, Penor Rinpoche arrived at Catharine and Michael's brick rambler in Kensington to stay for four or five days. The basement was crowded with Catharine's students, waiting to meet him. Trunk after trunk was unloaded from the car. Two mattresses were separated and put on the floor of the guest room. And after a brief speech about Buddhism, the lama retreated to his bedroom, where he kept to himself most of the following day. Catharine and Michael heard chanting, and clanking bells, coming from the room. They smelled burning cedar. One of the lama's trunks, Michael learned later, was full of books. Another held ceremonial objects. He remained closeted for hours as he practiced.

The next night, Michael and Catharine had a vegetarian meal with tofu and chamomile tea delivered to Penor Rinpoche's bedroom--assuming that Buddhists do not eat meat. After a few minutes his attendant came out.

"His Holiness wants to know what else you have to eat."

"What .... else?"

"His Holiness says this tea tastes like hay."

"What does he like?" Catharine asked.

"Steak."

It was on the second or third day in Kensington that Penor Rinpoche became a bit more sociable and ready for sightseeing. Michael and Catharine took him to the National Zoo -- they were told he loved animals -- as well as the Smithsonian, the Capitol, and several of their favorite memorials. Over lunch at Thai Taste on Connecticut Avenue, the lama began asking Catharine questions about her classes. "What do you teach?" he asked through an interpreter. Catharine explained about the Light Expansion Prayer, the meditations she'd invented over the years, and her lectures on "oneness" and "voidness" and "no-thingness." Penor Rinpoche seemed particularly interested in how she'd been able to attract students. He would be happy to meet with the students individually, if they'd be interested.

"We had no idea how important he was," Jetsunma recounted years later, "or how to treat a lama. We walked in front of him. We stood over him, and sat down next to him. All of these things I would never do now -- nobody would -- and on the last day, we threw a barbecue in my backyard in his honor, and served him potato chips and hot dogs."

It was on the last day that Penor Rinpoche gathered Catharine and her students in the Kensington living room and made a dramatic announcement -- through Kunzang Lama, acting as interpreter. Catharine had been teaching Mahayana Buddhism without any formal instruction. Penor Rinpoche attributed this miraculous ability to many lifetimes of Buddhist practice, performed at such a high level that it would always be in her mind. Michael turned to look at Catharine. Her eyes never strayed from Penor Rinpoche.

"You are all Buddhists," the venerable lama told the group. "And you are already practicing Buddhism."

He asked them to echo him as he uttered a string of words in Tibetan--words that went untranslated. "It was really like, Repeat after me," Wib remembered, "and we all did it."

Years later, after they had founded KPC -- and many of Catharine's students had become ordained monks and nuns--they were still discovering what the words meant, and how their lives had been changed by them.

I dedicate myself to the liberation and salvation of all sentient beings. I offer my body, speech, and mind in order to accomplish the purpose of all sentient beings.

I will return in whatever form necessary, under extraordinary circumstances, to end suffering. Let me be born in times unpredictable, in places unknown, until all sentient beings are liberated from the cycle of death and rebirth.

Taking no thought for my comfort or safety, precious Buddha, make of me a pure and perfect instrument by which the end of suffering and death in all forms might be realized. Let me achieve perfect enlightenment for the sake of all beings. And then, by my hand and heart alone, may all beings achieve full enlightenment and perfect liberation.

I take refuge in the Lama.

I take refuge in the Buddha.

I take refuge in the Dharma.

I take refuge in the Sangha.

_______________

Notes:1. According to Ephraim Katz, The Film Encyclopedia, 2d ed. (New York: HarperPerennial, 1994), the actor who played Ben Casey was named Vincent Zoimo, not Deoli.