by Jackson Barnett

The Denver Post

PUBLISHED: July 7, 2019 at 6:00 am | UPDATED: July 7, 2019 at 12:39 pm

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Ariel Hall sits in her home in Spruce Head, Maine, on June 7, 2019. Hall formerly lived and worked at the Shambhala Mountain Center in the foothills west of Fort Collins. Hall said that when she sought help getting out of an abusive relationship with a fellow Shambhala member, the Buddhist organization’s leadership encouraged her to meditate and told her the abuse was “good material” to work with.

Ariel Hall loved her Tibetan meditation cushion, a maroon-and-saffron pillow that helped melt away the strains of daily life during visits to her local Shambhala center.

She began meditating as a curious New York University undergraduate, her intrigue eventually drawing her to Colorado, the birthplace and a present-day hub of her chosen strain of Buddhism.

Ariel Hall formerly lived at the Shambhala Mountain Center. She said her efforts to get help from leadership in extracting herself from an abusive relationship at the center fell on deaf ears.

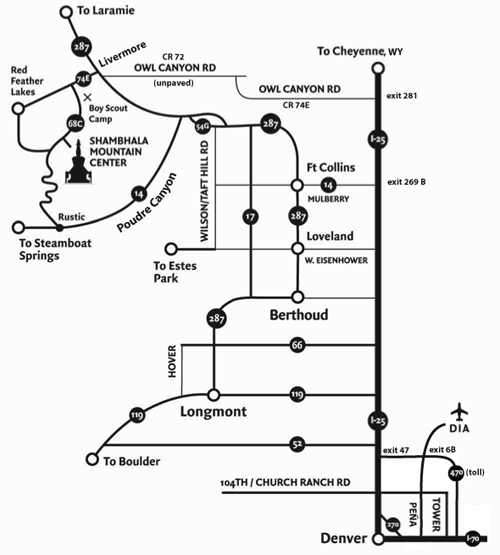

But after Hall in 2008 moved to the Shambhala Mountain Center — the international Buddhist organization’s sweeping 600-acre meditation grounds in the foothills west of Fort Collins — she faced a challenge that going to her cushion couldn’t solve.

When Hall sought help extricating herself from a relationship with a fellow Shambhala member who had become abusive, she said her requests fell on deaf ears. Instead, Hall said she was told by the mountain center’s leadership that she should take it “to the cushion” — the abuse was “good material” to work with.

“When I was hearing over and over again to meditate, what I heard was, ‘This situation is not wrong, you are wrong,’” she said. “It was victim-blaming.”

Hall’s experience wasn’t unique.

Shambhala, the Boulder-born Buddhist and mindfulness community, for decades suppressed allegations of abuse — from child molestation to clerical abuse — through internal processes that often failed to deliver justice for victims, The Denver Post found through dozens of interviews with current and former members and a review of hundreds of pages of internal documents, police records and private communications.

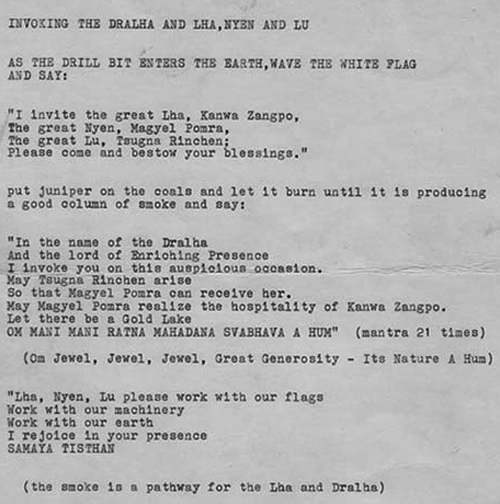

That suppression came in the form of worshipful vows students said they were told to maintain to the very teachers that alleged abused them; in explicit and implicit commands not to report abuse; and through a cultish reverence that served to protect Shambhala’s king-like leaders, according to interviews and third-party reviews commissioned by Shambhala itself.

“The problem is that we thought we had a way of doing things that was better, more compassionate, more grounded than the conventional way,” said Craig Morman, a former Rusung, or safety commander, at the Shambhala Mountain Center. “It was arrogant and reckless.”

Shambhala International, now based in Nova Scotia, Canada, has been mired in controversy over sexual and clerical abuse for the last year, with its leader — Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, who has deep ties to Boulder — having stepped back from his duties after being accused of sexual misconduct. Some of those allegations were corroborated by third-party investigations commissioned by Shambhala.

“It is a very painful time for our community. There is broad agreement that our culture failed to support many of those who’ve been harmed since Shambhala’s founding 45 years ago,” Melanie Klein, director of the Boulder Shambhala Center, said in an email to The Post.

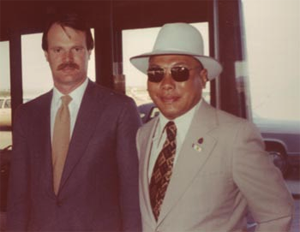

Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, left, the leader of Boulder-born Shambhala International, presents the Living Peace Award to the Dalai Lama at the Shambhala Mountain Center in Red Feather Lakes, west of Fort Collins, in 2006.

“Keep it in the Buddhist community”

Detectives in Colorado have been investigating sexual assault allegations with ties to Shambhala for months — and records from a recent arrest detail an apparent effort to shield a suspect from prosecution by addressing the allegations within the Shambhala community.

Last year, Larimer County sheriff’s detectives opened an investigation into what a Boulder police report describes as sexual assaults at the Shambhala Mountain Center. Larimer sheriff’s officials declined to elaborate, but last week confirmed their probe remains ongoing.

POLICE SEEK ADDITIONAL VICTIMS

Boulder police said they believe there are more victims in both the William Karelis and Michael Smith cases, and asked that they — or anyone victimized by “any other member or former member of the Boulder Shambhala” — call Detective Ross Richart at 303-441-1833. There is no statute of limitations in Colorado on sex crimes involving children under 15.

The first arrest came in February, when former Boulder Shambhala meditation instructor William Lloyd Karelis, 71, was booked on suspicion of sexually assaulting a young girl he mentored in the early 2000s. Karelis has denied the allegations through his attorney.

After the arrest, Shambhala officials acknowledged they had initiated mediation with Karelis — ultimately revoking his credentials — after women alleged he had behaved inappropriately with them. But Shambhala leadership denied prior knowledge of the sexual assault allegation.

Late last month, Boulder police arrested a second former Shambhala member, Michael Smith, 54, on suspicion of sexually assaulting a teenage girl he met through the Buddhist community in the late 1990s. Those allegations originally had been reported to Boulder police in 1998 after the victim informed one of her mother’s friends about what she said happened — but Smith wasn’t named as a suspect or arrested.

The girl’s parents told police they met with Smith, members of the Shambhala community and therapists at the time, and Smith agreed to go into therapy and have no contact with the victim or other children “in exchange for (the girl’s parents) not providing his name to the police department,” according to Smith’s arrest affidavit.

William Karelis enters the courtroom at the Boulder County Jail on Feb. 1, 2019. Photo by Paul Aiken, Daily Camera file.

Michael Smith appears in court on June 28, 2019. Photo by Cliff Grassmick, Daily Camera file. Both men are former members of the Boulder Shambhala Center who were arrested this year on suspicion of sexually assaulting children they met through the Buddhist organization in a pair of unrelated, decades-old cases.

Dozens of pages of investigative reports released by Boulder police last week further suggest an effort was made by Shambhala members in 1998 to deal with the allegations against Smith as an internal matter.

One former Shambhala member who knew the victim’s family told investigators that “everyone wanted to keep it in the Buddhist community” rather than go to police. A woman identified as Smith’s girlfriend at the time told police a spiritual teacher advised the girl’s parents “not to send Mike to jail and not to press charges, but to deal with it in a way that would teach Mike a lesson.”

SEXUAL ASSAULT, DOMESTIC VIOLENCE RESOURCES IN COLORADO

Denver Sexual Assault Hotline: thebluebench.org. Call the hotline at 303-322-7273 for free, 24-hour help.

National Domestic Violence Hotline: thehotline.org. Call the hotline at 1-800-799-7233 for free, 24-hour help.

Violence Free Colorado: Use this map to locate resources by county in Colorado. The website also has resources like a guide to helping someone you know who is being abused.

SafeHouse Denver: safe-house-denver.org. Reach local professionals by calling the 24-hour crisis and information line at 303-318-9989.

Moving to End Sexual Assault (MESA): movingtoendsexualassault.org. Call the 24-hour hotline at 303-443-7300.

Steve Louth, Smith’s attorney, told Boulder’s Daily Camera newspaper that Smith admitted to “unlawful behavior” at the time as part of a restorative justice agreement and subsequently completed an extensive sex-offender treatment program.

That restorative justice program was facilitated by a Shambhala member named Dennis Southward, according to Boulder police reports. Southward, in an interview with detectives last month, characterized the 13-year-old victim as someone “who was exploring her own sexuality,” according to a report.

The Shambhala Interim Board released a statement saying it had not been aware of the allegations against Smith, but since his arrest, “concerns arose related to the handling of this case internally by Shambhala leaders in the 1990s.”

The organization’s governing board said it will hire a third-party investigator to review how the allegations against Smith were handled. Furthermore, Shambhala said it has suspended Southward “from all leadership positions” pending that investigation.

“The views expressed by Mr. Southward in the (Boulder Police Department’s) incident case report do not represent the opinion of the Shambhala organization nor its leadership,” the board said.

In an interview with The Post, Southward said the handling of the allegations against Smith in 1998 “was not a Shambhala issue,” insisting he was the only member of the Buddhist organization involved in the discussions with the girl’s family. The Boulder investigators’ reports, however, refer to other Shambhala members and teachers being part of those talks.

The Great Stupa of Dharmakaya is seen at the Shambhala Mountain Center near Red Feather Lakes in the Larimer County foothills in this undated photograph.

“Loose” attitude around sex

The Shambhala Mountain Center, where Hall said her abuse was left largely unaddressed, faces allegations that its own leadership neglected reports of harm, interviews with former students show.

Karuna Thompson, a former Shambhala Mountain Center staff member, said she tried to report what she and others believed to be a sexual relationship between a middle-aged staffer and an underage girl in the late 1990s. When Thompson and a fellow staff member tried to alert leaders to the potential sexual activity, she recalled feeling treated like she was the problem.

“Ultimately we were made to feel like a nuisance,” Thompson said.

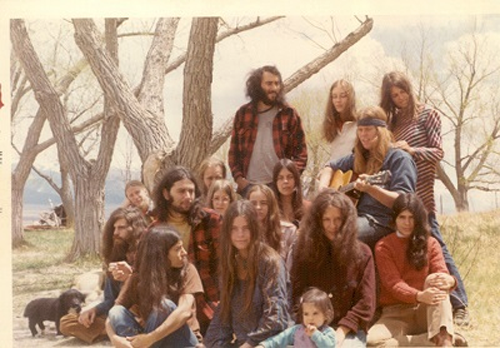

In the start-up days of Shambhala there was a “loose” attitude around sex, said Jim Becker, who was a student of founder Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche in the 1970s. While Becker said he did not directly witness physically abusive sexual relationships, he said he often saw older men approach young women for sex.

“It was like rock stars with the groupies,” Becker said of the scene at the Shambhala Mountain Center, then known as the Rocky Mountain Dharma Center.

Thompson described the Shambhala scene in the 1970s and 1980s as a collision of free love and Trungpa’s “crazy wisdom” philosophy. Trungpa, who died in 1987, preached pushing boundaries in life, in love and in all ways of seeing the world. Thompson said she saw the age gap between men, women and even girls engaging in sexual activity as one of those collapsing boundaries.

“Every young girl I knew had something happen,” Thompson said.

Becker recalled seeing the community ostracize young women who didn’t want to sleep with Trungpa. Thompson also recalled similar pressure for young women and girls to have sex with Trungpa and the men in his court, she said.

Leslie Hays, who in 1985 became one of Trungpa’s multiple “spiritual wives,” known as Sangyum, said Trungpa physically struck her and was emotionally abusive during their relationship. Their “marriage” — complete with its own Shambhala-issued marriage certificate, which The Post reviewed — began when Hays was 24 and Trungpa was 45. Trungpa’s first wife, Diana Mukpo, married Trungpa in Scotland in 1970 when she was 16 years old.

“He could shoot someone on Fifth Avenue and people would still think he is the king,” Hays said about Trungpa, echoing then-candidate Donald Trump’s famous line.

Leslie Hays stands in her mother’s home in Princeton, Minnesota, on June 11, 2019. In 1985, Hays said, she became one of Shambhala founder Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s several “spiritual wives.” Hays said Trungpa was emotionally abusive during their relationship. Their marriage began when Hays was 24 and Trungpa was 45. He died in 1987.

Liz Craig, another woman who spent time at the mountain center, said she often was approached by older men for sexual relationships when she was a teenager growing up in Colorado’s Shambhala communities in the 1980s. Many of the older men she entered into relationships with were in the inner circle close to Trungpa. Reporting the underage sex was out of the question for Craig, even when she said the men became physically violent. Shambhala felt to her like its own universe with its own rules, she said.

No one interviewed by The Post said they reported information to the police about underage sex in the early days of Shambhala.

For Becker, Hays and Craig, Shambhala’s reverence for its leaders made it feel like a cult. “People would be ostracized who didn’t toe the party line,” Becker said of his time in Shambhala in the 1970s.

Addressing misconduct often fell through the cracks due to ignorance of how to properly deal with abuse, interviews show. Those tasked with handling abuse were volunteers, a lack of expertise that the Interim Board has acknowledged was part of the problem.

Several current and former Shambhala leaders, including Mipham, could not be reached or declined to be interviewed.

In a written response to questions emailed by The Post, Shambhala’s Interim Board acknowledged failures in properly addressing harm. Specifically, the board stated that Shambhala’s Care and Conduct processes — the organization’s overarching policy to address conflicts with officeholders — did not do enough.

“Many issues have contributed to Shambhala’s Care and Conduct challenges over the years,” the board said, “including: a policy that did not apply to all members of the community; failure to enact the policy in certain situations; members’ discomfort with the reporting procedures; and lack of proper training for leaders in implementing the procedures.

“We fully acknowledge that all of these issues have contributed to the situation we find ourselves in as a community, and we strive to do better.”

No faith in the system

Pam Rubin, a former Shambhala student, said she was kissed without her consent by a high-ranking teacher during a retreat in Vermont in 2005. After it became public, representatives of Shambhala asked her to attend a Care and Conduct meeting.

As a professional counselor who works with trauma victims, she saw the dangers in participating. She said the format — which brings alleged victims and those accused together — is potentially re-traumatizing without adequate support.

“That process is part of the problem,” Rubin said. “There is no way in hell I was going to get involved in that.”

In 2002, Shambhala International’s Board of Directors created the overarching policy of “Care and Conduct.” It was designed to use Shambhala’s contemplative teachings to address complaints against officeholders — such as meditation instructors or center employees — using Shambhala philosophies.

In a document that outlines the policy, the then-board explicitly stated that the process was not made in the mold of traditional justice or arbitration systems, but instead an arbitration “informed by the profound view of basic goodness.”

Despite being the new system to internally address harm, Care and Conduct was not widely adopted or even understood, according to a report prepared for Shambhala by An Olive Branch, an organization that consults with religious groups on preventing abuse. Claims of misconduct often fell into the hands of people at centers and were not properly passed up the chain to the International Care and Conduct Panel in Halifax, Nova Scotia, the report said.

In the wake of the allegations against the 56-year-old Mipham, Shambhala appointed a process team of nearly 100 members to restructure how the Buddhist organization handles abuse, including Care and Conduct. The board plans to raise funds to hire full-time professionals for handling misconduct, the board said in its statement to The Post.

While Care and Conduct has been seen as ineffective, there was a noticeable gap in who it even covered. Mipham, Shambhala’s spiritual leader, was not required to sign a 2015 pledge to abide by updated Care and Conduct policies that included a pledge to not have sexual relationships with students, An Olive Branch found.

Shambhala leader Sakyong Mipham Rinpoche, right, and other Buddhist monks stand amid smoke from burning juniper as they await the arrival of the Dalai Lama at the Shambhala Mountain Center in Larimer County in 2006.

A protected leader

Mipham stepped aside in July 2018, acknowledging he had caused “harm” in past relationships. Since then, he has issued few statements and remains in retreat in India at his wife’s family monastery. His future remains largely uncertain.

A third-party investigation commissioned by Shambhala found what it characterized as two credible allegations of sexual misconduct against Mipham.

In one of those cases, Mipham drunkenly kissed Julia Howell in 2011, the investigation found. The report concluded the encounter qualified as “sexual misconduct.” (The report only labeled Howell as “Claimant No. 1,” but Howell confirmed that was her in interviews with The Post.)

Friends of Howell who were close to Mipham reached out to her after the incident, telling her to keep her stringent vows to Mipham and not to speak about it.

The third-party report found there may have been “some degree of collusion to set a particular narrative” about the misconduct by witnesses to the event who were close to Mipham. “There may have also been an attempt to discredit (Howell),” the report states.

The Boulder Shambhala Center is pictured in 2016.

“This is a (expletive) cult. What happens when you stand up to authority? You get pushed out,” Howell said in an interview.

While Mipham had systemic cover for his behavior from his position as Shambhala’s leader, those close to him had social protection as well.

Juliana McCarthy told The Post that when she was the victim of a domestic-violence incident initiated by a member of Boulder’s Buddhist community, she was explicitly told by two members of Mipham’s court not to report it to Boulder police.

Slow to no reform

Even though many at the upper levels of the Shambhala Mountain Center and Shambhala International, and those close to Mipham, were repeatedly told about problems in the organization, little effective reform was implemented, internal communications and interviews with those who tried to warn Shambhala show.

Rubin, the counselor who said she was forcibly kissed in 2005, sent reports to Shambhala about its handling of her and other instances of alleged sexual misconduct. The response from Shambhala to the red flags Rubin tried to raise did not lead to the reform she’d hoped for, she said. She had to “pull teeth on every level” to be heard.

“They have this knowledge and they are not doing anything about it,” she said.

During retreats to implement structural change at the Shambhala Mountain Center, Morman — the former Rusung, or safety commander — said he saw senior teachers filibuster basic conversation over reforms with soliloquies on Buddhist philosophy. Change was stopped before it could even start, he said.

“Until I started getting involved with running stuff, I didn’t realize how bad it was,” Morman said.

Others who raised questions felt that adherence to Shambhala teachers stifled them. Vows and oaths that students took to their teachers bound them into roles of devotion and obedience. Trungpa and Mipham each commanded great power over their students through these vows.

Leslie Hays, who said she was one of late Shambhala founder Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche’s several “spiritual wives,” visits the woods near her mother’s home in Princeton, Minnesota, on June 11, 2019.

Hays, one of Trungpa’s several Sangyum, or wives, said the vows she took bound her spiritual husband’s abuse inside of her. The times she said that he hit her with his walking stick and required her to carry and prepare cocaine lines for him were cemented inside of her for decades out of fear of being sent to “vajra hell,” the fate for those who break their stringent vows, she said.

“Shambala is particularly fraught with these oaths and pledges of allegiance,” Hays said.

The report by An Olive Branch noted that Mipham’s role as both spiritual and administrative ruler was a position ripe for abuse. Now that Mipham is in India with his remaining Kusung and wife’s family, it is unclear who will fill the large void he has left.

Mipham has sent emails through his secretary David Brown — who declined to be interviewed — that allowed students to release their vows with him. But he remains legally entangled with Shambhala and his name is still attached to its image, and his proxy entities are still listed throughout Shambhala’s governing documents.

“I just see all these people trying to keep something going, but in my perspective, it ended with my father passing,” said Gesar Mukpo, Mipham’s half-brother and son of Trungpa. “It is a sad state of affairs.”