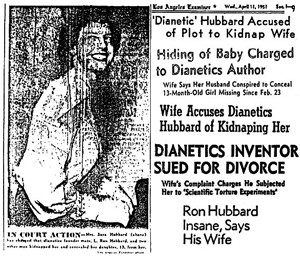

by Tom Bell

December 12, 2006

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

CT Business Card for Gold Lake

A sangha-owned oil and gas company

It’s been twenty-five years since Gold Lake Oil folded and Rinpoche said, at the end of our last meeting: “I still have faith that something will happen in the future, but maybe our ambition killed the whole thing.” In this article, I would like to begin to tell the story of Gold Lake Oil. Needless to say, this is my own version of events that took place, and I hope others will chime in, correct any errors and add memories of their own.

Gold Lake Oil started quite simply. At the first Kalapa Assembly, Rinpoche gave a commentary on the Letter of the Golden Key Which Fulfills Desire, one of the root Shambhala texts, which he received as terma. In his talk on October 15, 1978, he introduced the notion of yün or inherent richness. During the question period for this talk he was asked to speak further about yün, and as part of his answer Rinpoche said:

Maybe we should have an expedition to go hunting for yünand if we dig further, we might find oil. It’s possible, you know. I have already found water at Karme Chöling. That actually was based on the same principle. It’s projecting, looking for yün. Remember the story? Maybe we should tell people. Maybe Bill should tell it.

William McKeever: When we were building the extension at Karme Chöling, and we needed a new water system for the added population, we employed about three well companies in the area to find the proper spot. None of them agreed, but they began digging—at seven dollars a foot. And after three dry holes and several thousand dollars, somebody thought of asking the Vajracarya where we should dig the well. He picked a spot when he was there, and said to go down about two hundred feet, I believe, and that we should get a lot of water. Well, we went down about two hundred feet and hit next to nothing, and thought of stopping. The well drillers had their pride and wanted to find another hole. I happened to be out in Boulder at the time, and the Vajracharya said, “I think you should go a little further,” which sounded like the usual advice. So we decided to give it a try, and went about twenty feet further and hit one of the highest producing wells in the whole county. The well drillers couldn’t quite figure it out: it was about fifteen feet from a site they had drilled previously and hit nothing. But it seemed to have worked quite well. I asked Rinpoche how he picked the spot and he said it was very easy. He said that just as we can see an emotion on somebody’s face, he could just look at the land and see where the water was. It is hard to understand, but it seemed to work quite well.

-- Excerpted from COLLECTED KALAPA ASSMBLIES, page 66. Used here by permission of Vajradhatu Publications and Diana Mukpo. © 2007 by Diana J. Mukpo.

John Roper was in the audience for this talk and called me the next day. I returned his call from a pay phone in South Texas. He knew that I had just found work in the oil business and thought that I might be interested in exploring for oil with Trungpa Rinpoche. I immediately said that I would try to help through my connections with Craig Thompson, who is a fellow sangha member and a friend, and his father, John R. Thompson, who is quite successful in the oil and gas exploration business in Texas. Internally my reaction to making the commitment to explore for oil was something like panic (actually it was panic) as I had just found work that looked like it would provide a good, steady income for my family (which included our son who was born at RMDC and was soon to include a new baby girl) and now I had agreed to start actually exploring for oil instead of simply getting paid to help others explore for oil. Now I had to start thinking in terms of hundreds of thousands of dollars instead of thousands of dollars. Suddenly the risks were much larger.

When Rinpoche arrived in Colorado in the fall, his students rented a small cabin for him in the mountains above Boulder, near an old mining town called Gold Hill. It was quite spartan, almost what you would call a stone hut. There was no indoor plumbing, just an outhouse. Rinpoche hadn't lived in a place like this since he'd left Tibet more than ten years ago. People may have thought a Tibetan lama would be more comfortable in a simple mountain setting. This might have been more a reflection of his students' hippie aspirations than an accurate reading of who he was at this point. On the other hand, it was by no means a hovel, and he told me that he enjoyed himself there. The house was on a beautiful piece of property, with a view of the Continental Divide in the distance. It was owned by a family that had spent years in the foreign service in Asia. This was their summerhouse, which they named Gunung Mas, which is Burmese, I believe.

-- Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chogyam Trungpa, by Diana J. Mukpo with Carolyn Rose Gimian

Actually, the oil and gas industry was the last thing I thought would become a part of my life. In 1966, six years before I became a Buddhist, I dropped out of graduate school, rejected an offer from the U.S. State Department to become a Foreign Service Officer, and became a full-time activist—working for peace, civil rights, and the environment. Yet here I was being invited into the oil and gas industry as more than just an employee and hearing myself say “yes” without much hesitation. What had changed? I (like most of my friends in the community) was eager to work more closely with Rinpoche, to be a part of his vast project of bringing dharma to the West. So I suppose you could say it was a mixture of devotion and ambition. In any case, I was already working within the system that I had rejected during my activist days, and now I was about to move much more deeply into that world.

John Roper was my good friend, and also a Vajradhatu board member and the lawyer for the organization. He was willing to help with the legalities of exploring for oil and he was also willing to invest in the idea. He became the attorney for our exploration company, soon to be called Gold Lake Oil, and he did the legal work to set up a limited partnership with a group of investers who wanted to share in the journey, and were willing to take on part of the financial risk.

Within our business activities, Trungpa Rinpoche asked us to refer to him simply as Mr. Mukpo, his family name. He said that this would be in keeping with business tradition. On February 12, 1979, Mr. Mukpo hosted a group of sangha members at his home, the Kalapa Court, in Boulder. These were people who had expressed an interest in investing with Gold Lake. This meeting followed the first Gold Lake exploration trip to West Texas. At that time, Mr. Mukpo said:

Obviously, it is based on, as far as I am concerned, my own intuition and faith and delight in getting into this particular business . . . I would like to say that I feel extremely good about the oil business. Also, I would like to say that I have had my resistance in the past in connection with this kind of project, which seemed to be based on abusing the land and becoming rich quick. All sorts of neurosis could be involved with those kinds of situations. But by visiting the particular land that we have seen, I felt extremely good because I feel that our project and our endeavor is real. We are not particularly abusing anything at all. It is like cutting flowers and putting them in a vase.

There still is that sense of moral question, however. There is still the issue of how much we abuse the land and try to get as much as we could and then just leave pure garbage behind. That is my basic and very, very main concern. A lot of examples of Americana have happened in that way, not only in abusing land but how we abuse people at the same time. When people are useful they are cherished and when they are lacking inspiration and useless we kick them out and they may become unemployed. So there is a big concern overall about the whole thing—how we work with our land, how we work with our particular project connected with the land. It is like when we built retreat huts at Karme Chöling and Rocky Mountain Dharma Center. We tried to build those huts as best we could so that we did not rape the land but rather so that we could somehow balance the situation together with what exists in the environment.

On that particular idea, that you are not abusing the land but you are cherishing and bringing something out of the land, that was one of my passionate feelings when we went to Texas and were looking at these oil fields. The whole thing was extremely good. That particular place we saw with the juniper bush was a very interesting experience. It was very uplifting and felt good. You are making a relationship with earth. However, that may be philosophy. The intuition that is involved with that is not particularly 100% security for your investing in it. I should say that definitely. So please be careful, considerate. Still, the atmosphere when you open your mind to oil and the possibilities of it, instead of aggression and depression, I felt extremely uplifted and fresh, very fresh and extremely good, extremely good.

-- Unpublished remarks by Chögyam Trungpa used by permission of Diana J. Mukpo. Transcribed from recording of Gold Lake investors meeting, February 12, 1979.

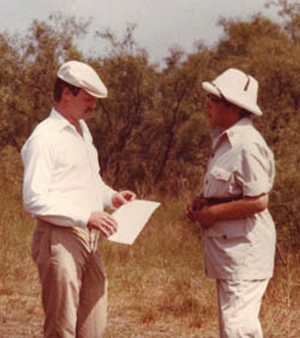

Tom Bell and CT Mukpo in Abilene, TX

My wife, Jacquie, had just received a small inheritance from her grandparents and Craig and Karen Thompson had some money available so we decided to pool our resources and start to explore for oil with Rinpoche. We started by showing him maps of drilling prospects in the Abilene area of West Texas that had been leased by John R. Thompson’s company, along with maps showing the location of a drilling prospect that Craig Thompson had identified, without yet securing the drilling rights. Good traditional geologic arguments could be made for the existence of commercial levels of petroleum in the subsurface rock formations of each of these prospects. Rinpoche found the maps to be very interesting and wanted to go to the locations and walk on the land so that he could feel the energy of the place and see the land itself. His approach to finding oil and gas is hard to characterize, but it had a lot to do with relating to the fundamental energies of the land. At one point, he referred to this as invoking and following drala.

Tom Bell and CT Mukpo on an oil prospect in West Texas

We organized the first of what would become a series of oil exploration trips to the Abilene area of West Texas. There was one prospect that particularly interested Rinpoche. His interest was perked initially by the landowner’s name on the map. The name was “Bright”—Icy Bright, as it turned out. When we visited this land, he liked it very much. The land lay between two hills that seemed to make an appropriate formation and there was a juniper bush that was auspiciously placed. He told us, “Drill here.” We placed a stake in the ground at that exact spot, and he said, “Feels good.” He also selected drilling sites on two additional prospects during this first trip, but our initial efforts focused on what became known as the Juniper Bush/Two Hills prospect located on Bright family lands then owned by Mrs. Icy Bright of Tyler, Texas.

Everything seemed very ordinary on our exploration trips. Rinpoche would sometimes doze off in the car as we traveled from one prospect to the other. There did not seem to be any expectation that we would ask dharma questions, or engage in discussions about the teachings. Traveling with Rinpoche in this simple way was completely enjoyable. He made a point of giving a good tip at the diners where we would eat, and of being friendly with the people we would meet, such as the waitresses or the landowners. He talked about the importance of always telling the truth with our investors and in our business relationships generally. He had ideas for uplifted offices and a good logo for the company. It seems that all of these things were part of invoking and following drala, but that was not explicitly stated—these were simply the right ways to do good business.

If I had thought about it . . . if I had even had a glimpse of my own naivete in terms of both dharma and business, I might have been too afraid to even try to find oil in Texas. But at the time, I thought of myself as a good and devoted student. I was halfway through my Vajrayogini practice; I had been the head of practice and study at RMDC; I was a teacher and a meditation instructor. So, full of pride and ambition, with great faith in Mr. Mukpo’s ability to make things work, I found myself sitting on the ground with my stop watch, waiting to confirm the presence of oil thousands of feet below my bum.

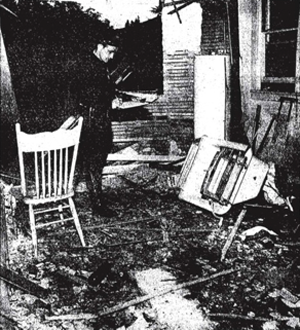

At the signal from Rinpoche, Mr. Perks would detonate the explosives

I was sitting there engaged in a particular form of seismic testing that Rinpoche had invented for Gold Lake. After he would select a likely drilling location for oil, he would ask the company managers and investors who were traveling with him to sit with him in a circle on the ground around the possible drilling location. John Perks would place a circle of small explosive charges around the group with an electric wire connecting them so that they could be detonated simultaneously. At the signal from Rinpoche, Mr. Perks would detonate the explosives, creating an experience of instant nonthought for the entire group inside the circle, followed instantly by fear of hearing loss. We would then quickly start our stopwatches, focus on the feeling of our butts pressing against the earth, and wait for the sound vibrations to bounce off the oil reservoir and return to the surface where we could feel them. When these vibrations appeared, we would press the stopwatches again to record the elapsed time. If we mostly had the same elapsed time it would confirm our experience of the vibrations. The idea was that, if the location lacked oil, we would not feel any returning vibrations and that the longer the time it took for the vibrations to return, the deeper the oil reservoir was from the surface.

The Gold Lake exploration crew at work

Rinpoche would have liked us to drill the Juniper Bush/Two Hills prospect first, but it turned out that the lease rights to drill a well on the prospect were not readily available. It took more than two years to put these leases together. In the meantime, we acquired a working interest in several other prospects that were drilled. One of these was completed for production but never produced commercial quantities of petroleum. Gold Lake was not the operator (the company that actually did the drilling) on any of these early prospects.

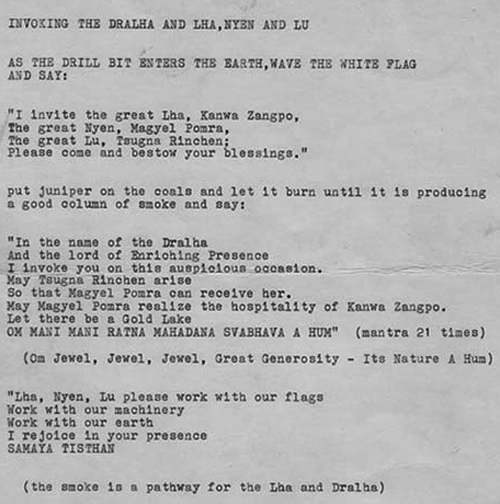

However, when the leases for the Juniper Bush/Two Hills prospect (later known as the Bright #1 Well) were finally secured, Gold Lake Oil served as the operating company. This gave us control over certain events that were important to us. We were able to make sure that the drilling took place on the exact spot Rinpoche asked us to stake during his first visit to the site. We were able to do a lhasang ceremony at the time when the ground was first being entered by the drill bit, and to put offering rice into the initial hole drilled for the surface casing. With this ceremony, we were formalizing our intentions. We were inviting the dralas to come to this place, to work with our machines, and to help by bringing forth the wealth of the earth for the benefit of all beings. Rinpoche composed a chant for this occasion. [See liturgy below.] The rice we put in the hole was given to Rinpoche by His Holiness the Sixteenth Karmapa for this express purpose. We were also able to camp on the site while the well was being drilled and to help catch and analyze the geological samples to see how the drilling was progressing, and if the samples contained petroleum.

© 2007 by Diana J. Mukpo, used here with her permission

It was an interesting kind of meditation retreat to live in a tent next to a drilling rig that operates twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week. The sounds that are associated with keeping the drill bit turning to the right become a way of life. Listening for subtle changes that indicate moving from one rock formation to another—formations with different densities and/or hardness—holds one’s attention like few other objects of meditation in my experience. The routine included watching the process while the drilling crew (commonly known as roughnecks) added another length of drill pipe every thirty feet as the well deepened. Watching this process, I got to know the roughnecks a bit and learned more about the drilling process from them. I learned, for example, that rattlesnakes are naturally attracted to the vibrations created in the earth by the drilling process, and that the roughnecks had a little side business of catching rattlesnakes and selling them for meat.

Our main target was the Gray Sandstone formation with a secondary target of the Morris Sandstone formation. Both of these rock formations were known to be porous and permeable enough to be good reservoir rocks for oil and gas in this area. These formations were also overlain by non-permeable rock formations that provided a good trap for the petroleum, so it could not leak upward out of the reservoir formation. Both of these formations had been found to give good production levels in the area where we were exploring. To get a producing well in these formations one needs to find a place which is like the top of an old hill, now buried under thousands of feet of newer rocks. We had the electronic logs from nearby wells that had been drilled both with and without finding commercial production. These logs showed the depth of the various formations that we would be drilling through and thus provided markers, like a vertical map, so that we could tell if we were running high or low to these marker wells. The samples that we gathered and analyzed helped us to confirm what formation we were drilling through at the time.

” …drill deeper…”

As we came near to the Gray Sand, our anticipation was a solid thing. We collected the samples and noted the change of drilling speed. Analysis of this showed that we were running high to nearby dry holes, but low to nearby producing wells. We had not hit oil or gas in our target formations but we had encouraging signs that we were drilling on the slope of these formations and that there might be “higher ground,” so to speak, if we went deeper. There was a largely unexplored potential below our target zones called the Ellenberger formation. The Ellenberger was starting to create interest in the area and some producing wells had been found there. We had the example of the water well at Karme Chöling where, by going deeper, excellent water had been found. Mr. Mukpo, who we talked with regularly by phone whenever we were drilling, thought it would be a good idea to drill deeper to the Ellenberger, which was right above the granite bedrock and therefore the deepest possible production zone in this area. It was about 4,500 feet below the surface. So we drilled deeper.

It was slow going as there was a conglomerate formation above the Ellenberger that was very difficult to drill through. It was taking at least ten minutes per foot to go through this rock. The drilling is measured on graph paper attached to a rotating drum. A mechanical pen draws a line across the graph each time the drill bit makes it through another foot of rock. There is a distinctive set of sounds associated with the process of the drill bit going deeper. By this time it was impossible for me to not hear that set of sounds standing out in the midst of all the myriad of other sounds of the rig. All of a sudden the rig started to drill at three minutes per foot. This would be the top of the Ellenberger, and it sounded porous. After three feet of this faster drilling I asked the driller to stop so that we could get a proper test of the top of the zone. It takes awhile for the samples to come up from 4,500 feet and it is good to look at them before drilling deep into the formation.

It definitely looked like we had struck it rich.

The samples from the Ellenberger showed petroleum. It was time for a drill stem test. The roughnecks raised the drill pipe and lowered a test chamber down the hole. Before the test chamber was opened, a hose was run from the pipe to a bucket of water so that we could tell if the formation was allowing anything to come into the pipe. As soon as the test chamber was opened, bubbles began to escape from the hose. Then the hose was closed off and the pipe was opened out over the mud pits. Very quickly it blew oil over the pits followed by the screaming sound of natural gas. The testing crew lit the gas, and a very impressive flame roared and lit up the day. It definitely looked like we had struck it rich.

Flaming natural gas from Bright #1 drill stem test

The Bright #1 Well was primarily a natural gas well. We completed the well for production but could not start actually producing the gas until the well was connected to a natural gas pipeline system. It took about eight months to get the pipeline contract and to have the gas gathering company construct the pipeline to our well. The wells in the immediate area were oil wells producing from the Gray Sand so there was no gas pipeline in the immediate vicinity. The pipeline company built the line at their cost because they believed that the Bright #1 Well would produce sufficient quantities of gas to cover their investment. It also appeared that the Bright #1 Well represented a new discovery in the Ellenberger that would result in other gas wells in the area. The construction of this pipeline seemed to confirm the belief that Gold Lake Oil was now a financially successful exploration company. There remained one nagging question mark. There had been a slight draw down in pressure during the drill stem test. Experienced people at John R. Thompson’s operating company cautioned that this often indicates a limited reservoir, meaning that the well might not produce for long, but that there was no way to know for sure except to prepare the well for production and see what happened.

The directors of Gold Lake: CT Mukpo, Craig Thompson, and Tom Bell

It is difficult to make decisions such as whether or not to complete a well for production. There is some objective information, and there are uncertainties. Rinpoche stressed that the key issue in making these decisions is to always tell the truthboth to ourselves, and to the people who would be affected by our decisions. The owners, investors, and employees of Gold Lake Oil went on a journey of exploration together. We did our best to communicate openly and truthfully with each other. We maintained good looking offices and had a beautiful logo. We kept our financial affairs in good order and always paid the bills on time. We were generally kind and caring with each other, at least between klesha attacks of various kinds. Still, I think it is safe to say that everyone involved relied upon Rinpoche to be the one who embodied the dharma, and who invoked and followed drala. To one degree or another, the rest of us thought that we could benefit from his attainments without really doing the hard work of giving up our own self-clinging and personal ambitions.

As we waited for the Bright #1 Well to be connected to the natural gas pipeline there was a kind of muted euphoria within the company. We were confident that we were rich, so during our wait we started to explore further. We looked at prospects in Nova Scotia, Kansas, and Colorado and we designed a major lease play on the Ellenberger formation. We had an important discovery well in the Ellenberger, so it was only sensible for us to gather drilling rights in the area where this formation was known to be present and prospective.

We tried to keep up the production but kept getting more and more salt water.

When the Bright #1 Well was finally brought into production the initial results were positive. We were able to produce 100,000 cubic feet of gas per day. This meant that our well was bringing in about $300 per day for a projected $110,000 per year. This would not be a quick payout of the cost of drilling and completion, but it would eventually provide a good return on investment if it held up and other wells could be added to the field at a lower cost than the initial discovery well. However, the well started to produce some salt water along with the gas after a few weeks. We tried to keep up the production but kept getting more and more salt water. Now we knew that the draw down in pressure during the drill stem test did, in fact, mean that we had discovered a limited reservoir of natural gas. We were no longer rich, at least not in terms of dollars.

Around the time that we had to plug the Bright #1 Well, the price of oil started to drop dramatically. It went from a high of $42 per barrel in 1981 to $30 per barrel in 1982 and to $10 per barrel in 1986. Practically the whole oil and gas industry in North America stopped taking new, unproven drilling leases, and the number of rigs drilling for oil in the United States at any one time dropped from a peak of 4,500 in 1982, to 2,000 in 1983, and to 750 by 1986. The economics of the business changed dramatically in a very short time. Still, Gold Lake did not give up. We went ahead and drilled another well, the Hobbs #1, on leases we had acquired during our efforts to put together prospects in the Ellenberger. We were no longer very interested in the Ellenberger, but the Hobbs leases had other interesting target formations and Rinpoche had found a good location on the Hobbs lease.

While drilling the Hobbs #1 Well we had a good drill stem test that flowed oil and did not draw down in pressure. It did not take long to complete this well as there was no need for a natural gas pipeline connection, but we were very aware of needing a successful well with long-term production. This time we were more skeptical about whether we were really rich, so we waited to see how the production would hold up before we tried to acquire any more leases in the area. The Hobbs #1 went to salt water even more quickly than the Bright #1. By now, both the managers and investors in the company were losing heart, and the drop in oil prices was making it hard for any company to justify further exploration.

“… maybe our ambition killed the whole thing”

At the final meeting of Gold Lake Oil, held in December of 1982, Mr. Mukpo said, “Well, I still have faith that something will happen in the future, but maybe our ambition killed the whole thing.” He only said it once, and he said it reflectively.

These words were a mind stopper when I heard them 25 years ago, and they continue to be a mind stopper when I read them now. It is certainly true that we were ambitious, and in retrospect, it wasn’t just your average garden-variety ambition for wealth and success. We had the added hook of spiritual ambition. To some extent, I think that we were naively drilling for some sort of spiritual goodies that seemed at the time to be inseparable from the promise of oil and gas. But in spite of everything—our financial losses and our foiled personal ambitionsI think it would be shortsighted to see Gold Lake Oil as a failure. He said:

” …I still have faith that something will happen in the future,…”

And it has. Many members of our community, including some of the original Gold Lake owners and employees, have gone on to be successful in the world of business—successful in terms of the bottom line, and successful by less conventional criteria as well. Some have even found oil and gas by applying what they learned from Mr. Mukpo. Personally I feel incredibly grateful to have been in business with Rinpoche—to have witnessed his attention to detail, to have heard his admonition to tell the truth, and to have had my own ambitions exposed so thoroughly by the prospect of sudden wealth.

Many of us—students of Trungpa Rinpoche who have been involved in business—are retired, or nearing retirement age. Perhaps it would be worthwhile at this point to step back and take a look at our collective experience. What do we have to say about being in business and being practitioners? How has this activity contributed to the project of planting dharma in the West? How has it helped and/or hindered the creation of an enlightened society? What are our measures of success? Perhaps we could use the Chronicles as a forum for this discussion.

Yours in the practice of the dharma and commerce,

Tom Bell,

Halifax

© 2006-2007 Thomas Bell

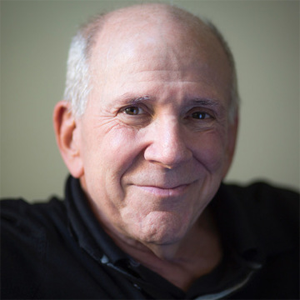

Tom Bell

Tom Bell joined Trungpa Rinpoche's community of students in 1972. He served as the head of practice and study at Rocky Mountain Dharma Center (now SMC) in the mid-to-late seventies, before entering the oil and gas business in 1978. In addition to Gold Lake Oil, Tom co-founded Colorado Gathering and Processing Corporation, which supplied natural gas to the city of Greeley, Colorado. He also co-founded the Colorado Natural Gas Assistance Foundation, which used profits from natural gas sales to help low income energy consumers pay their heating bills. Tom and his wife, Jacquie, and their children, Wilson and Victoria, moved to Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia in 1988, where he has been involved in a number of business and community projects. Most notably, Tom served as the general manager for the conversion of a former Canadian military base (CFB Cornwallis) into the village of Cornwallis Park. After serving as the Director of Karme Chöling from 2000 through 2003, Tom and Jacquie have returned to Nova Scotia where (recently retired) they study and practice the dharma between visits with their children and grandchildren.

Shastri Tom Bell became a student of the Vidyadhara in 1972, and has been active since then in direct service to both of the Sakyongs and also to the current Sakyong Wangmo. He was on the staff of RMDC (Shambhala Mountain Centre) in the mid,’70’s, was the director of Karme Choling from 2000-2003, and has been an active Shambhala teacher since 1976. He has worked to support his family through a career in business and economic development in Colorado and Nova Scotia. His immediate family now numbers fifteen, including his wife, three children, their spouses, and seven grandchildren. He was appointed as a Shastri for Halifax in 2015.

Shastri Tom Bell, by shambhala.org