You Are Avalokiteshvaraby Eric Holm

Lion's Roar

January 1, 2002

Eric Holm on how visualization practice helps us overcome ego and pacify obstacles. Includes “A Visualization Practice: Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion.”

Eric Holm on how visualization practice helps us overcome ego and pacify obstacles. Includes “A Visualization Practice: Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of Compassion.”The buddhadharma is renowned for its skillful methods of meditative training. In Vajrayana Buddhism, many of these methods are based on the visualization of archetypal wisdom forms, or deities.

Visualization practices come from a very profound point of view. For generations of practitioners over more than a thousand years, such practices have been pivotal in overcoming the basic problems of the ego’s self-centeredness, emotional fixations, and frozen perceptions.

For those not acquainted with these seemingly strange practices, they may raise a host of questions:

• Where do these deities come from?

• Are these actual beings or symbolic forms?

• How do these images express spiritual inspiration and spiritual training?

• If the highest realization in Buddhism is formless emptiness, what is the usefulness of these images?

• How do these practices differ from the worship of deities in theistic spiritual traditions?

Mind Works in SymbolsActually, visualization is not foreign to us. Our mind works in images and symbols all the time. Many of our daydreams and memories, even our most fleeting thoughts, arise as images. Our inner aspirations and ideals, as well as our thoughts of authority figures, lovers and adversaries, all may come in images.

What Vajrayana does is to exploit the image-making activity of our mind that is already taking place and turn it into a skillful means.

However, there are some important differences between the ongoing visualization process of our habitual thoughts and the use of visualization in meditation. First of all, unless we have trained ourselves to work with our thoughts, our usual visualizations with their overlay of associations and transferences are largely involuntary. In fact, these images are the very medium of our emotional torment and confused projections.

Second, the emotional charge associated with these images is generally not free flowing. It tends to be fixated into one emotional pattern or another, such as desire, depression, jealousy or anxiety.

Finally, we are often not aware of these visualizations as being our own thoughts or mental productions. We may not recognize how our subconscious imagery mixes with our actual perceptions and colors how we see the world. So in many cases our mind’s image-making is a source of confusion and entanglement, rather than a source of opening.

What Vajrayana does is to exploit the image-making activity of our mind that is already taking place and turn it into a skillful means. We should be clear at the outset that the wisdom archetypes visualized in Vajrayana are definitely not separately existing external beings, in the way that theistic traditions often present deities. Rather, these are symbolic manifestations of buddhanature, the potential for awakening inherent in every living being.

Grasping and Fixating: The Creation of Self and OtherIn the Buddhist view, the root of all negativity is our ignorance of the true nature of life, consciousness and the universe, and our attempt to grasp and solidify what is ever changing and ungraspable.

The original ground of being is vast openness and spontaneously present, radiant basic intelligence. This is reflected in the buddhanature within the mind-stream of every living being. Ignorance of this intrinsic radiance and fear of its limitless openness results in a process of shrinking down, obscuring and distorting the basic intelligence. What results is the frozen, dualistic mind-body-and-world we are so familiar with.

This process, called “ego clinging,” has two aspects. The first is the grasping and centralizing of experience around an instinctive “I, me, and mine.” The second is fixating on solidified meanings and frozen perceptions of the universe. Though described as two aspects, the creation of a self and its positioning in a frozen universe are two sides of one coin.

The buddhanature in us represents tremendous creative potential, yet our habitual being is blinded and distorted by the ego process of grasping and fixation. This results in the continual recreation of our confused being, burdened by fear, limitation, and conflicting emotions.

Buddhanature: The Ground, Path and FruitionThe term “buddhanature” refers to our own innate wisdom and compassion. Often our buddhanature emerges spontaneously in acts of kindness, courage and inquisitiveness, yet at other times it is obscured by our clinging to small identities, imagined securities, and emotional fixations. Buddhanature also manifests as a gnawing dissatisfaction, a search for deeper meaning in life. This is buddhanature manifesting as the ground, the innate potential in everyone, whether realized or not.

Increased openness to ourselves and to the world comes from letting go again and again of self-centered thoughts and habitual storylines.

We can also speak of buddhanature as the path. As a result of meditative training, a constructive approach to life, and good spiritual guidance, we begin to let go of obsessive thoughts and small identities. We experience increased openness to ourselves and to the world. This comes from letting go again and again of self-centered thoughts and habitual storylines. Instead, we settle into a genuine sense of being, our buddhanature, which is said to be composed of openness, compassion and insight. It is our true nature, so to speak.

Finally, there is buddhanature as the fruition, the state of being of those who are fully realized. This manifests as the three kayas, or bodies, of the awakened state. They are the dharmakaya, sambhogakaya and nirmanakaya.

The dharmakaya, or “body of the dharma-nature,” is the completely unbounded being of the awakened state. It is beyond form, beyond experience, beyond relative time and space. It is the creative potential within and behind everything.

The sambhogakaya, or “body of complete enjoyment,” refers to the unceasing, spontaneous emanation of compassion, which aims to liberate all beings who live in a contracted, fearful, dualistic consciousness.

Finally, through the nirmanakaya, or “body of emanation,” the dharmakaya and sambhoghakaya are actually embodied, for instance in the physical presence of an accomplished master or in the form of the wisdom archetypes.

Vajrayana PracticeIn the Vajrayana view, our life stands on a twofold ground: the ground of our confused being and also what permeates it—this tender inquisitiveness of buddhanature, which is something very powerful. So in common with all Buddhist traditions, Vajrayana takes our confused being on the path as something to refine and purify. In addition Vajrayana takes our buddhanature on the path as something to bring out and acknowledge. The wisdom deities that are visualized manifest the illuminating force of the buddhanature that is present in us, and in this sense we bring the wisdom of fruition to the path.

When we refer to the wisdom deities as symbolic, we don’t mean they are mere symbols. They are dynamic images that reveal the wisdom, compassion and potency of the buddhanature that empowers them. They are symbols of a state of being that combines profound awareness of how things actually are with the active and transformative power of that awareness. As the Heart Sutra says, “Form is no other than emptiness, emptiness is no other than form.” The Cajrayana deities express this inseparability of emptiness and its dynamic activity.

But how is it that such images actually spark the insight of emptiness-form in our minds, rather than being just another mental projection or some neurotic fantasy? This is a crucial question that goes to the heart of what visualization practice is about.

The answer is twofold. First, the practices function this way because they are empowered by direct transmission from a teacher who represents a living lineage of realization. Second, their effectiveness depends on appropriate preparatory training of the student-practitioner.

Visualizations are sometimes given to beginning students as objects for mental stabilization, and this is entirely valid. Nevertheless, on the whole, the visualization of the wisdom deities is an advanced practice that needs to be understood in the context of Buddhist meditative training in general.

The Development of Mindfulness and StabilityTo understand visualization practice, we have to understand something of the progressive stages of meditation. Only in this way can we understand the state of mind from which the wisdom archetype meditations arise. In the buddhadharma, the meditative journey begins with taming and pacifying the mind. The crucial element in this is mindfulness.

In Buddhism our initial task is to recognize our thoughts as simply thoughts, rather than as ultimate realities, and to make friends with the unruly cacophony of forces that is our inner world.

Even though the ordinary disciplines of life can bring us some mental focus, the inner landscape of our mind often goes unnoticed. By holding our attention to the breath or another simple object of focus, our mind becomes sharper and we become aware of a flood of mental activity. In mindfulness meditation, we acknowledge the thoughts, emotions, projections, hopes and fears that arise and dissolve in our mind, without judging any of them as good or bad.

Therefore, in Buddhism our initial task is to recognize our thoughts as simply thoughts, rather than as ultimate realities, and to make friends with the unruly cacophony of forces that is our inner world. We accept everything that arises, and let it go. Accommodating this inner chaos becomes a means of taming it. Holding to our object of focus and recognizing our repeated distraction serves to interrupt the obsessive train of thoughts and preoccupations, so that over time we develop some inner peace and stability.

The Development of CompassionThe buddhadharma, like most spiritual traditions, emphasizes the importance of compassion and empathy. There is the obvious suffering of people in extreme distress, such as refugees from a civil war, and of people suffering loss, grief, illness or poverty. However, a more subtle suffering and struggle pervades all of life, even among people in fortunate circumstances. Life brings continual challenges, anxieties and disappointments, and the suffering we experience in our own life can reduce our arrogance and increase our empathy. So compassion arises, first of all, from our own experience of suffering and our awareness of others’ predicaments.

Compassion arises in a second way from our gratitude and affection for those close to us-our parents, mentors, friends and children. Starting with this universal instinct of compassion, we can then undertake deliberate meditation on loving-kindness that removes possessive attitudes and expands our compassion more universally.

Third, compassion arises as an inherent quality of awareness. As such, it manifests warmth and communication toward all beings and all things, without history, without memory, without cause or reason. This boundless compassion is one aspect of the Vajrayana deities.

Connection with a Spiritual MasterFundamentally, our spiritual development is our own responsibility. Nevertheless, a relationship with an authentic teacher who embodies a lineage of spiritual instruction brings immeasurable help. Such a teacher has gone through much training and is aware of the many sidetracks and blind alleys that spiritual practitioners may get themselves into, as well as the various ways they can resist the process of waking up.

A competent teacher will know how to instruct aspirants stage by stage, according to their capabilities. But the inspiration of such a teacher goes beyond guidance and instruction. An evolved teacher also manifests an enlightened state of being, and the atmosphere of wide-open mind, compassion, directness and wakefulness around such a teacher is very inspiring.

The teacher’s example is not mere charisma in the ordinary sense; it is authenticity of being. From the presence of such a person, one gains confidence that the awakened state is not just a myth from the past. It is real and can be realized by people of the present generation. This brings confidence, a deeper glimpse into the nature of one’s own mind, and a sense of admiration, respect and devotion.

It is by acknowledging the feast of our ego clinging that we learn to transform confusion into wisdom.

Devotion in the Vajrayana arises from trust in the dharma, gratitude for the benefit one has received, and longing to realize one’s true being, which is inseparable from the teacher’s realization. Sometimes devotion is misunderstood as placing oneself in a dependent position and regarding the teacher as an all-wise parental figure. No doubt the teacher’s wisdom and vision in spiritual matters is beyond our own. Nevertheless, taking such a dependent position is an obstacle that has no developmental value. Whether in the basic Buddhist approach of self-liberation, in the bodhisattva path of compassionate action, or in the Vajrayana discipline, what is called for is confidence in one’s inherent potential, trust in one’s own insight, and a brave, even heroic attitude.

At the same time, devotion to an authentic teacher allows students to open up to their most basic fears and neuroses and also to discover their most far-reaching potential. It is by acknowledging the feast of our ego clinging that we learn to transform confusion into wisdom. The ngöndro, or Vajrayana foundation practices, help to make this surrendering process deep-seated and real.

Change of AllegianceThe development of mindfulness, of compassion, and of a relationship to a genuine teacher brings about a certain change of allegiance in the practitioner. We begin to realize that our habitual aggressions, avoidances, indulgences, jealousies, slanders, arrogance and so forth are the source of only bewilderment and suffering. Gradually we lose faith in these habitual strategies. Both in our mind and behavior, we begin to shift our allegiance to a saner approach.

This change of allegiance is sharpened by several additional insights. First, we begin to realize that human life has a precious task-opening ourselves up to the spiritual foundations of existence. Our own existential restlessness, as well as our encounter with accomplished teachers, confirms this.

Second, we realize that our life is impermanent; its conditions are constantly changing. Life is unpredictable; however, it is certain that eventually we will have to leave this life and this body behind. At the time of death, our only resource will be the pattern of sanity and openness we have developed.

This realization of impermanence might bring with it a certain element of panic and groundlessness. We realize that although there are temporary securities, nothing in this life can provide the ultimate security we crave. All this brings a certain immediacy and urgency to our path.

Moreover, we can see that many people lead life in a way that is bound to be self-defeating in the long run. Not being in touch with our deeper nature, we suffer from spiritual emptiness, and no matter how many diversions we seek, that emptiness remains.

A Visualization Practice: Avalokiteshvara, the Bodhisattva of CompassionWhen our mind bears the imprint of the above foundations, we are ready to be introduced to visualization practice. As a result our training, when we visualize the wisdom deity it has the following qualities:

First, the visualization has the imprint of our teacher’s mind and the way he or she has pointed out the nature of mind to us. Second, it is stamped with the immediacy of mindfulness. Third, it has the nature of compassion. Fourth, it represents a change of allegiance from our habitual, fixated mind.

In Vajrayana there are three classes of visualization: the gurus, the wisdom deities, and the protectors. Commonly, we visualize our own root teacher in the form of Vajradhara Buddha or Guru Rinpoche. This expresses the insight that even though we meet our teacher in human form, his or her realization is continuous with the realization of the lineage as a whole. Second, we visualize the wisdom archetypal deities. These deities are always understood as inseparable from one’s own teacher and lineage. Third, we visualize assisting and protective forces, the dharma protectors.

To explain some further aspects of visualization meditation, we can go through the basic stages of a short practice of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion.

The Front VisualizationAt the beginning of the practice, we visualize the wisdom archetypal form, in this case the bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, in front of us and surrounded by the masters of the lineage. The front visualization represents the presence of higher wisdom and awareness that we, in our more undeveloped state, open to and aspire to emulate. It is good to cultivate the attitude that this visualization is not merely in our imagination, but that the wisdom mind and compassionate activity of the deity and our teacher are actually present. In this way our visualization can be empowered because it arises from our connection with our teacher.

At this stage, the visualization is an external object of refuge and devotion. Just as we take refuge in the Buddha as an example, the dharma as a path, and the sangha as companions, here we take refuge in the masters of the lineage and the sambhoghakaya deity forms as the embodiments of enlightenment. In their presence and with their support, we take refuge and also arouse a motivation of compassion.

Formless MeditationFollowing this, the visualization is dissolved into oneself, and one rests in the open awareness of formless meditation. This dissolves any boundary between the visualized form and the meditator and opens us to the deeper awareness of unconditioned mind. Here, the afterglow of the visualization practice and the inner clarity it provoked is merged with the unstructured mind of complete openness.

This is the emptiness phase of the meditation session. Vajrayana practices always alternate between these two phases—between dynamic but transparent form, and empty awareness pervading whatever arises. This formless phase of meditation is also influenced by whatever direct instruction the student has received from her or his teacher concerning the intrinsic nature of awareness.

Following this state of unstructured awareness, the self-visualization is invoked.

The Self-VisualizationWhen we have completed the Vajrayana foundation practices, or ngöndro, which have made our being more open and workable, we may be empowered to visualize ourselves in the form of the deity. In this case it is that of Avalokiteshvara, the bodhisattva of compassion. The reason we do this is to acknowledge the buddhanature within ourselves by identifying with Avalokiteshvara’s nature of compassion and emptiness.

Each deity practice has its own special characteristics, which should be learned through the oral instruction of one’s teacher. However, several points are emphasized concerning all these practices: a vivid but empty form, recollection of the significance of the deity, and an uplifted mind full of confidence in one’s inherent potential.

During the form, or “generation” stage of the meditation, the deity’s symbolic form serves as the focus for mental stabilization. This form is like a rainbow or a body of light—empty and transparent. Thus it is the union of appearance and emptiness, rather than a solidified mental projection. There is a definite object to engage the mind, but it is held loosely and openly. At the same time, the image is evocative. In the case of Avalokiteshvara, he is handsome, white and very radiant, shining with lights of the five wisdoms, smiling and gazing compassionately, peaceful and contemplative.

While visualizing the form of the deity one also meditates on its significance. We understand that Avalokiteshvara’s body is empty and translucent because he is free of clinging to concepts, ordinary forms and solidified emotions. His faultless form symbolizes complete freedom from all the negativities that should be abandoned. His four arms symbolize the four immeasurable qualities of loving-kindness, compassion, sympathetic joy and equanimity. In his heart center is a seed-syllable that represents his wisdom mind, which is inseparable from the mind of the teacher. His ultimate nature is the union of compassion and emptiness.

Furthermore, one should have an uplifted mind and the conviction that the deity is a real representation of our nature. We are not imagining something that is not so; we are acknowledging the wisdom-compassion nature that is actually present within us, in order to manifest it further. Sometimes we might find this perspective encouraging, and at other times demanding.

Beyond this, special instructions concerning the meaning of the visualization are received orally from one’s teacher, especially concerning how to unify the visualization practice with the recognition of the mind’s essential nature.

Having manifested the deity, we call down additional blessings from the lineage and then begin the recitation of the appropriate mantra. While some mantras have conceptual content, this is not primary; on the whole, they are the manifestation of the deity in the form of speech and inner energy.

Following the visualization period of the session, the deity dissolves into one’s heart center and one again rests in formless meditation. This serves as an antidote against thinking of the deity, or of oneself, as a solid external entity or a focus of neurotic grasping.

Vajrayana SymbolismThe images of the Vajrayana deities arose within the experience of realized practitioners as wisdom display. Therefore, they are not like the projections of conventional mind. Traditionally, these images were often kept secret because they are symbols of inner transformation, transmitted to the meditator by the teacher. Of course, in Tibet they became quite well known because the culture was so thoroughly permeated by the Vajrayana tradition. Today in the West one can see these images on calendars or in art books, but needless to say, the inner experience of these images is quite different from what can be grasped by looking at a book. They were never intended as poster art.

While the peaceful deities might seem quite soothing and familiar, many of the semi-wrathful forms are somewhat paradoxical and shocking, from ego’s comfort-oriented point of view. They are splendid, magnificent, beautiful and awe-inspiring, but at the same time they might be cutting and menacing.

Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche emphasized that these archetypal forms are transcultural. They do not belong to any ethnic background; rather, they address raw and rugged energies of human existence, which are universal. Apart from elements of royal Aryan garb that some of the peaceful deities wear, they do not wear Chinese or Indian or Tibetan costumes. Instead, they wear elephant skin cloaks and tiger skin skirts. They wear ornaments of human bone, which remind us of death, impermanence and renunciation, and as adornment, they wear ashes from cremation grounds. They brandish various scepters, implements, and weapons. Their moods are peaceful and contemplative, friendly and magnetizing, outrageous and gallant, threatening and menacing.

Peaceful, Wrathful, and Semi-Wrathful ArchetypesSome deities, such as Avalokiteshvara, present a peaceful way of magnetizing us into openness. However, we are not so easy to tame by peaceful methods alone. We have lots of conflicting emotions and entrenched arrogant attitudes. Therefore the semi-wrathful and wrathful deities are made to order for people like us. They can communicate directly to the raw and rugged qualities of our conflicting emotions—they help to provoke, uproot and transmute them. This type of practice makes many demands on the practitioner. One has to have a very clear understanding of the intent of the practice, the confidence to jump into the purifying fire, and the willingness to ride one’s mind and emotions in all situations of life.

The semi-wrathful and wrathful deities are made to order for people like us.

The semi-wrathful or wrathful forms do not mean the deities are angry. Rather, they are dynamic: their energy can manifest in whatever way is necessary to tame and transmute. For instance, the semi-wrathful deities are often described as “enraged against the four maras,” which represent personal and societal ego-fixation. The four maras are the skandhamara, the deception of clinging to solidified personality; the kleshamara, the liability of getting lost in storms of conflicting emotions; the devaputramara, which entails the arrogance and complacency of god-like existence, exemplified by forgetting one’s bodhisattva motivation; and mrytumara, the obstacle of death and interruption. These are the obstacles the wisdom deities help us to overcome.

Lineage Gurus, Wisdom Deities and Dharma ProtectorsWhen we visualize the masters of the lineage, our main emphasis is tuning into the support, blessing, and realization of the tradition as the basis for everything that follows. Then, the meditation on the wisdom archetypes is as briefly explained above. Finally, based on our relation with the master and the wisdom deity, we also invoke the assistance of the dharma protectors, who embody action principles of awareness. An example of such a protector is Vajrasadhu, whose image is on the cover of this issue.

The protectors’ role is to create reminders for the practitioners if they lose their discipline, and to help pacify or subdue obstacles and neurosis in the physical or psychic environment. Their form is often wrathful, as an expression that liberated awareness can reach without hesitation into the raw and rugged energies of existence to tame and transmute them. The result of the protectors’ activity is to restore situations to a workable and wholesome ground.

ConclusionVajrayana practice is based on recognizing that the confused ground of our being is also permeated by the presence of buddhanature. Therefore, under the guidance of an authentic teacher and lineage, we can practice by employing fruitional principles of awareness on our path. These principles are both without form and with form. This kind of practice is very helpful but it also demands real surrendering of one’s ego-agendas. It requires appropriate preparation and real commitment to fundamental sanity.

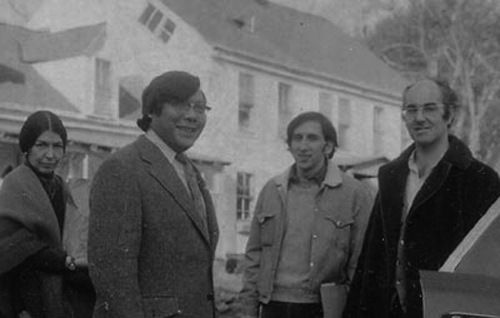

ABOUT ERIC HOLM

Dorje Loppön Eric Holm, a close student of the Vidyadhara Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche, was appointed by him to oversee practice and study at Vajradhatu centers from 1976 until 1991. As Dorje Loppön he was responsible for the hinayana, mahayana, and especially vajrayana training of students. As well as teaching dharma and Shambhala Training programs, he currently works as a technical lead in a software company.