Part 4 of 4

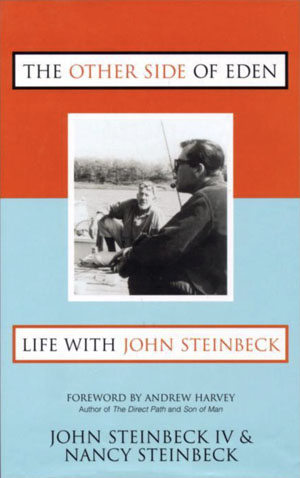

66. The Steinbecks wrote: ‘The Naropa poetry department, the Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics, hosted a weeklong Kerouac Festival that summer [1982]. All the poets from the first summer at Naropa were back and this time, Ginsberg and Corso, Ferlinghetti, William Burroughs, Kesey, and Norman Mailer were hanging out at our house. A video production company was filming them daily in our living room.’ Steinbeck IV, John & Nancy Steinbeck. (2001). The Kerouac Festival. In The Other Side of Eden: Life with John Steinbeck (Kindle ed.). Amherst: Prometheus Books. The most prominent poets in this group were Robert Bly, William Burroughs, Gregory Corso, Allen Ginsberg, W.S. Merwin, Ed Sanders, Gary Snyder, and Anne Waldman.

67. William Stanley Merwin (b. 1927 d. 2019) was a two-time Poet Laureate. Author unknown. (Date unknown). About W.S. Merwin. Merwinconservancy.org. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

68. For extensive discussions of what became known as the ‘Merwin Affair’ or the ‘Naropa Poetry Wars,’ see: Investigative Poetry Group. (1977).

The Party: A Chronological Perspective on a Confrontation at a Buddhist Seminary. Woodstock: Poetry, Crime, & Culture Press. In 1977, John Steinbeck IV was interviewed about the affair by Al Santoli of the Investigative Poetry Group. Steinbeck first met Merwin in the autumn of 1974 at Chögyam Trungpa’s Dharmadhatu center in New York City. Ibid. pp. 17, 18, 20. See also: Clark, Tom. (1980). The Great Naropa Poetry Wars: With a copious collection of germane documents assembled by the author. Santa Barbara: Cadmus Editions; Steinbeck IV, John & Nancy Steinbeck. (2001). Introduction. In The Other Side of Eden: Life with John Steinbeck (Kindle ed.). Amherst: Prometheus Books. After Merwin and Naone had left the 1975 seminary, shortly before it ended, a young boy died in the room they stayed in. Looking back, Trungpa’s wife Diana puts this tragedy in the context of the Merwin affair and the struggle with their own son Taggie’s disabilities: ‘In some way, this incident was tied in for me to what was happening with Taggie. This was such a difficult time in our lives. In a certain sense, Rinpoche was dealing with extreme and seemingly unworkable energy at the seminary, while I was driving into a high wall of insanity (his phrase) in terms of Taggie and our family life. In fact, in a scenario that is unrelated yet strangely in keeping with the dark energies I’ve described, a child died at the very end of the 1975 seminary from complications of asthma while sleeping in the room at the hotel that Merwin and Dana had stayed in. (Although they stayed for the final talk of the seminary, they had left a bit earlier than others.)’ Mukpo, Diana J. & Carolyn R. Gimian. (2006). Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chögyam Trungpa. Boston: Shambhala. pp. 192, 211.

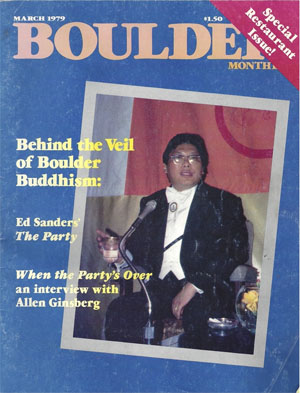

69. Visiting lecturer Ed Sanders and his class at Naropa Institute investigated the matter and completed an in-depth report in September 1977. Copies of this report circulated widely in Boulder until August 1978, when Sanders and his class decided to publish it. A lengthy excerpt appeared in the Boulder Monthly in March 1979. Investigative Poetry Group. (1979). The Party: A chronological perspective on a confrontation at a Buddhist seminary. Boulder Monthly, 1 (5), pp. 24-40. The same issue contained an extensive interview about the scandal with Alan Ginsberg: Clark, Tom. (1979). When the Party’s Over: An interview with Alan Ginsberg. Boulder Monthly, 1 (5), pp. 41-51. That same month, the Boulder Monthly’s editor Tom Clark reported on the affair and its cover-up in the Berkeley Barb under the pseudonym of Robert Woods. Woods, Robert. (1979). “Buddha-Gate” Scandal and cover-up at Naropa revealed. Berkeley Barb, 28 (13), pp. 1, 4. See also: Spaed, Sam. (1979). Buddha-Gate Revisited. Berkeley Barb, pp. 1, 6. In 1980, Clark published a comprehensive history of the events: Clark, Tom. (1980). The Great Naropa Poetry Wars: With a copious collection of germane documents assembled by the author. Santa Barbara: Cadmus Editions. See also: Goldman, Sherman. (1976). Robert Bly on Gurus, Grounding Yourself in the Western Tradition, and Thinking For Yourself: An Interview. East/West Journal, pp. 10-15; Marin, Peter. (1979).

Spiritual Obedience: The transcendental game of follow the leader. Harper’s Magazine, pp. 43-58; Reed, Ishmael. (1978). American Poetry: A Buddhist Take-over? Black American Literature Forum, 12 (1), pp. 3-11.

70. See endnote 66. The Dalai Lama visited the USA between September 3 and October 21, 1979.

71. Author unknown. (1979). The Nadir of Sectarian Squabbles. Tibetan Review, 14 (7), pp. 10-14. See also: Author unknown. (Date unknown). The Sixteenth Karmapa: Rangjung Rigpe Dorje. Kagyuoffice.org. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

72. Chögyam Trungpa was affiliated with both the Kagyü and Nyingma sects of Tibetan Buddhism.

73. Vajradhatu was the name of the umbrella organization of Trungpa from 1973- 1990. The term has a rich meaning in Vajrayana or Tantric Buddhism. Bernie Simon writes that Karl Springer later apologized to the Dalai Lama on behalf of Trungpa’s Vajradhatu community: ‘The Dalai Lama asked for an apology and wasn’t satisfied with the half-apology that Karl Springer wrote on behalf of Vajradhatu. So the Dalai Lama cancelled his plans to visit Boulder, a huge embarrassment for Vajradhatu and Karl Springer personally.’ Some years later, Simon says, Springer criticized the Dalai Lama’s visit to the Vajradhatu centre in Washington, D.C. after the Tibetan leader had left. Simon, Bernie. (2003). The Dalai Lama’s Plumber. Carelesshand.nfshost.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021. For responses to Springer’s letter by the Dalai Lama’s representative in New York and his secretary in Dharamsala, see Author unknown. (1979). The Nadir of Sectarian Squabbles. Tibetan Review, 14 (7), pp. 10-14.

74. Jeffrey Hopkins, who was the Dalai Lama’s interpreter on this tour, writes that the Tenzin Tethong, erstwhile head of the Office of Tibet in New York, ‘formed a committee to arrange the details of the visit, which focused on the content of the lectures and avoided any media hype.’ Gyatso, Tenzin (the fourteenth Dalai Lama). (2006). Kindness, Clarity, and Insight: The Fourteenth Dalai Lama, His Holiness Tenzin Gyatso (Revised and updated ed.). Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications. p. 8.

75. For extensive discussions of Tibetan exiles’ military collaboration with the Central Intelligence Agency, see: Mullin, Chris. (1975). Tibetan Conspiracy. Far Eastern Economic Review, 89 (36), pp. 30-34; Mullin, Chris. (1978). The Question of Tibet: Tibet and the I.C.J. China Now, May-June 1978, pp. 12-13; Author unknown. (Date unknown). The Shadow Circus: The Cia in Tibet.

Retrieved April 3, 2021; Sonam, Tenzing & Ritu Sarin. (2001). The Shadow Circus. Dharamsala: White Crane Films; Conboy, Kenneth & Morrison, James. (2002). The CIA’s Secret War in Tibet. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas; Dunham, Mikel. (2004). Buddha’s Warriors: The Story of the CIA-backed Tibetan Freedom Fighters, the Chinese Invasion, and the Ultimate Fall of Tibet. New York: Jeremy P. Tarcher/Penguin; McGranahan, Carole. (2006).

Tibet’s Cold War: The CIA and the Chushi Gangdrug Resistance, 1956-1974. Journal of Cold War Stories, 8 (3), pp. 102-130; McGranahan, Carole. (2010). Arrested Histories: Tibet, the CIA, and Memories of a Forgotten War. Durham: Duke University Press.

76. In his interview about the Merwin affair in the Boulder Monthly in March 1979, Alan Ginsberg repeatedly references the massacre in Jonestown, Guyana. Clark, Tom. (1979). When the Party’s Over: An interview with Alan Ginsberg. Boulder Monthly, 1 (5), pp. 41-51; Clark, Tom. (1980). The Great Naropa Poetry Wars: With a copious collection of germane documents assembled by the author. Santa Barbara: Cadmus Editions. pp. 52-67.

77. Hunter, Ann. (2008). The Legacy of Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche at Naropa University: An Overview and Resource Guide. Boulder: Naropa University. p. 8. Daniel Seitz writes: ‘Obtaining regional accreditation was a goal early on: by 1978, Naropa obtained candidacy status with North Central Association of Schools and Colleges (now the Higher Learning Commission), and achieved accreditation in 1985. In 1999, the Naropa Institute changed its name to Naropa University to reflect the expansion of its academic programs.’ Seitz, Daniel. (2009). Integrating Contemplative and Student-Centered Education: A Synergistic Approach to Deep Learning. University of Massachusetts, Boston. pp. 184-185. The Party reports about Naropa Institute’s co-founder Allen Ginsberg: ‘Ginsberg, fearing the loss of a $4000 grant to the Kerouac School from the National Endowment for the Arts, responded by initiating the “Merwin cover-up” (later known as “Buddha-gate”). He contacted both [Robert] Bly and Merwin and asked them to inform the NEA that there was no connections between Trungpa’s alleged misbehavior and Naropa or the Kerouac School.’ The grant application was turned down. Investigative Poetry Group. (1977). The Party: A Chronological Perspective on a Confrontation at a Buddhist Seminary. Woodstock: Poetry, Crime, & Culture Press. p. 26.

78. It seems likely that both Chögyam Trungpa and the 14th Dalai Lama occasionally received the same tantric teachings, initiations or empowerments from Dilgo Khyentse Rinpoché and other tantric teachers. In that event, their relation would have been governed by the tantric prohibition of critiquing a ‘vajra brother’ or their mutual tantric guru.

79. In 1960, the Dalai Lama appointed Chögyam Trungpa as the spiritual advisor to students at the

Young Lamas’ Home School in India. While there, Trungpa fathered a child on Könchok Päldron, a young Tibetan nun (see endnote 53).

Trungpa kept silent about the pregnancy, and held this office until 1963, when he received a scholarship to study at Oxford University in the UK. Looking back on the events of the day, Trungpa’s widow Diana Mukpo writes: ‘Around this time, Rinpoche received a Spaulding Scholarship to attend Oxford University. This had come through the intercession of Freda Bedi and John Driver, an Englishman who tutored Rinpoche in the English language in India and helped him with his studies later at Oxford. The Tibet Society in the United Kingdom had also helped him to get the scholarship. What’s the difference between a foreign accent and an exotic one? Chogyam Trungpa knew. He claimed to have an “Oxonian accent,” acquired during his “matriculation” at Oxford College. At least that’s how Diana, the first of Trungpa’s eight wives, put it in her

Dragon Thunder memoir, that details her maturation from child bride into den mother of a global cult devoted to the worship of her man, during a breathless two decades that passed in a whirl of booze, ménages-of-however-many, producing children from multiple unions who were uniformly recognized as reincarnated Tibetan saints and tossed to the winds.

Well, not the winds, precisely. Diana’s children, whether sired by Trungpa or Mitchell Levy, Trungpa’s close disciple, were cared for by devotees who treated them like born spiritual athletes –- asking them for spiritual advice, deferring to their presumed wisdom, etc. This did not do them much good, since they were mostly bemused by the unearned respect from clueless Buddhists, and didn’t take to the job of

pretending to be founts of Eastern wisdom. Diana certainly taught them little enough, while she sought shelter from domestic chaos by jetsetting from one horsey event to another, buying dressage horses with donor funds as the natural right of ecclesiastical royalty.

As for her much-declared devotion to her husband, Diana greased the skids to Trungpa’s grave, enabling his sordid fate –- death by self-induced coma due to drug abuse and organ failure -- one more rock star sucked dry by

the American celebrity-killing machine. Harsh as the assessment seems, evidence for it can be found on every page of Dragon Thunder, that has some of the candor that only the truly dissolute can exhibit. Their goalposts have moved so far, their judgment is faulty –- they can’t quite see when they’re confessing to scandal.

This poor judgment can lead to over-embellishing a cherished myth, as Diana did when she claimed that Trungpa “matriculated” at Oxford College in Dragon Thunder. Because that is a fact subject to verification or disproof, and I have obtained documents that disprove it, and I will share them with the reader. But before I proceed to that reveal, allow me to point out that these documents were not particularly difficult to obtain. It required only a modicum of research, emailing, and persistence in making followup inquiries to obtain them from Oxford College officials. Since virtually all formally published writing about Trungpa is mere hagiographic propaganda, we do not expect fact checking from the Dharma hacks who crank out these obligatory tomes. However, two books on Freda Bedi that pretend to be scholarly works were recently published, and they both repeated the apparent fable that she helped Trungpa get the Spalding sponsorship that "sent him to Oxford." So my question is -– why was I the first to make the enquiry of Oxford?

-- The Absent Oxonian -- Musings on Trungpa’s Faux Academic Credentials & Why So Few Cared to Inquire, by Charles Carreon

To go to England, Rinpoche needed the permission of the Dalai Lama’s government. They would never have allowed him to leave if they had known about his sexual indiscretion, nor do I think it would have gone over very well with the Tibet Society or his English friends in New Delhi. He and Konchok Paldron kept their relationship a secret, and it was a long time before anyone knew that Rinpoche was the father of her child. This caused him a great deal of pain, although I also think that he hadn’t yet entirely faced up to the implications of the direction he was going in his relationships with women. At that time, in spite of the inconsistencies in his behavior, he still seemed to think that he could make life work for himself as a monk.’ In 1971, the Dalai Lama named Trungpa’s second son, Taggie Mukpo (see endnote 55 and 56). Mukpo, Diana J. & Carolyn R. Gimian. (2006). Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chögyam Trungpa. Boston: Shambhala. pp. 72, 132.

80. Chögyam Trungpa’s widow Diana Mukpo writes: ‘In September 1979, His Holiness the Dalai Lama made his first visit to America. Members of the Dorje Kasung [Chögyam Trungpa’s bodyguards] were very involved in the visit. They organized motorcades for His Holiness’s party wherever he traveled in North America, and they worked with local law enforcement officials in major cities to help with crowd control and in general to provide security for His Holiness and his entourage. Trungpa asked Karl Springer to greet His Holiness on Rinpoche’s behalf when the Dalai Lama arrived in New York on September 3. Mr. Springer traveled to many cities with His Holiness to help assure that proper protocol was observed. In early October, when His Holiness returned to New York, Rinpoche, the Regent, and the entire board of directors of Vajradhatu flew to New York to meet with him. Rinpoche felt that it was extremely important for his senior students to meet the Dalai Lama, whom he himself had not seen for more than ten years. His Holiness and Rinpoche had several private meetings during the visit. Rinpoche was so happy that this great spiritual figure and the leader of the Tibetan world finally was setting foot on the American continent. I was unfortunately away for much of this, but I was able to meet and spend time with His Holiness in New York just before his departure from North America. I was arriving from Europe to attend the Kalapa Assembly and spend time with Rinpoche. Although His Holiness was not able to stop in Boulder during his first visit, when he returned in the summer of 1981, he spent about a week with our community, which was a great blessing for everyone. Mukpo, Diana & Carolyn Gimian. (2006). Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chögyam Trungpa. Boston: Shambhala (pp. 320-321). For an extensive discussion of the Dalai Lama’s first visit to the US, see Andersson, Jan. (1980). The Dalai Lama and America. The Tibet Journal, 5 (1/2), pp. 48-63.

81. Mukpo, Diana & Carolyn Gimian. (2006). Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chögyam Trungpa. Boston: Shambhala (pp. 320-321). Tom Clark suggests that Trungpa’s followers bought the March 1979 issue of the Boulder Monthly en masse, to take as many issues out of circulation as they possibly could. Clark, Tom. (1980). The Great Naropa Poetry Wars: With a copious collection of germane documents assembled by the author. Santa Barbara: Cadmus Editions. p. 38. In 1981, the Dalai Lama taught at the Naropa Institute and the University of Colorado in Boulder. Gyatso, Tenzin (the fourteenth Dalai Lama). (2006). Kindness, Clarity, and Insight: The Fourteenth Dalai Lama, His Holiness Tenzin Gyatso (Revised and updated ed.). Ithaca: Snow Lion Publications. p. 207-216.

82. Steinbeck IV, John & Nancy Steinbeck. (2001). Chapter 43: Icarus’ Flight. In The Other Side of Eden: Life with John Steinbeck (Kindle ed.). Amherst: Prometheus Books.

83. Ibid. Once again, note that the Dalai Lama’s remark was made in 1989 and remained unpublished until 2001.

84. Ibid.

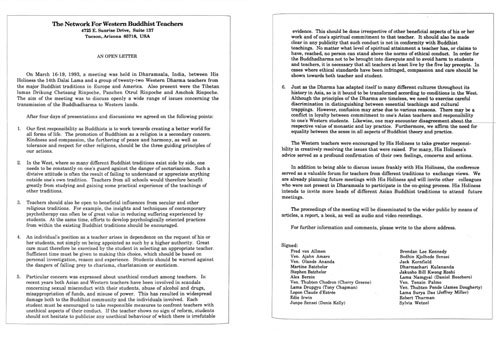

85. The entire conversation can be watched online: Author unknown. (1993). The Western Buddhist Teachers Conference with H.H. the Dalai Lama Frome: Meredian Trust.

86. See endnote 77. Mukpo, Diana J. & Carolyn R. Gimian. (2006). Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chögyam Trungpa. Boston: Shambhala. p. 320; Shepherd, Harvey. (1993, July 3). Dalai Lama had more to say than space allowed. The Gazette, p. H6; Smith, Kidder. (2001). Transmuting Blood and Guts: My Experiences in the Buddhist Military. Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

87. Shōkō Asahara’s death sentence was carried out on July 6, 2018—as it happens, the 14th Dalai Lama’s birthday.

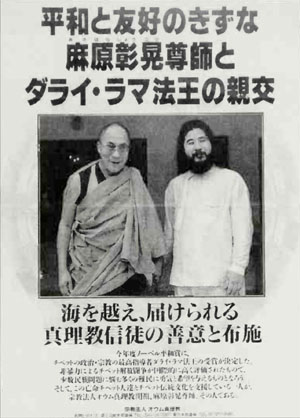

88. For a comprehensive reconstruction of the Dalai Lama’s involvement with Shōkō Asahara and the Aum Shinrikyō doomsday cult, see: Hogendoorn, Rob. (2020, December 5). Knave or Fool? The Dalai Lama and Shōkō Asahara Affair Revisited. Openbuddhism.org. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

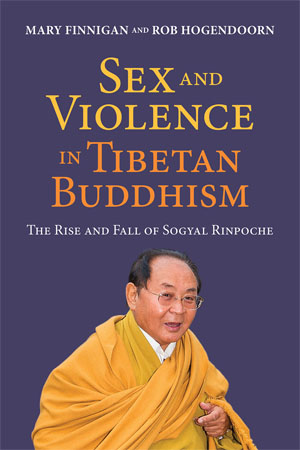

89. Sogyal Lakar (Wyl. bsod rgyal lwa dkar, b. 1947 d. 2019) was formerly known as Sogyal Rinpoché. For a comprehensive discussion of the life and times of Sogyal Lakar, see: Finnigan, Mary & Rob Hogendoorn. (2019). Sex and Violence in Tibetan Buddhism: The Rise and Fall of Sogyal Rinpoche. Portland: Jorvik Press.

90. Baxter, Karen. (2018). Report to the Boards of Trustees of: Rigpa Fellowship UK, and Rigpa Fellowship US: Outcome of an Investigation into Allegations made against Sogyal Lakar (also known as Sogyal Rinpoche) in a Letter dated 14 July 2017. Retrieved April 3, 2021. p. 39; Sogyal Rinpoche. (2008). The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying (Revised and updated ed.). London: Rider.

91. Lattin, Don. (1994). Best-selling Buddhist author accused of sexual abuse. Free Press.

92. An abbreviated version of the conference is available on DVD: Author unknown. (2011). In Conversation with the Dalai Lama: Highlights of the Western Buddhist Teachers Conference London: Gonzo Distribution. The entire conversation can be seen here: Author unknown. (1993). The Western Buddhist Teachers Conference with H.H. the Dalai Lama. Frome: Meredian Trust.

93. See, for instance: Sogyal Truth. (2017). Dalai Lama Speaks About Sogyal Rinpoche. YouTube.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021. For the Dalai Lama’s original address, see Gyatso (the fourteenth Dalai Lama), Tenzin. (2017). Inauguration of Seminar on ‘Buddhism in Ladakh.’ YouTube.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021. See also: Mees, Anna & Bas de Vries. (2018). Dalai lama over misbruik: ik weet het al sinds de jaren 90. NOS. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

94. Batchelor, Stephen. (2010). 16: Gods and Demons. In Confession of a Buddhist Atheist (Kindle Edition ed.). New York: Spiegel & Grau.

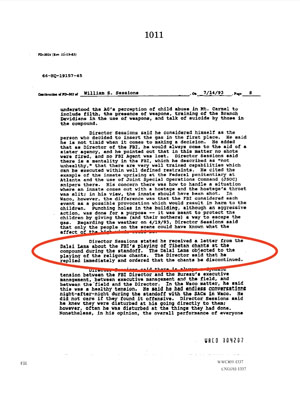

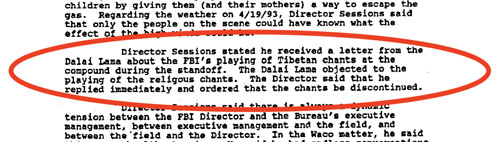

95. The Western Buddhist Teachers Conference was held from 13 until 22 March, 1993. Between 1990 and 1992, monks of the Dalai Lama’s personal Namgyal monastery released several CD’s, but it is unclear if these recordings were used in Waco. The Tibetan chants were played first on Sunday night, March 21, 1993. Boyer, Peter. (1995). Waco: The Inside Story. PBS Frontline. Retrieved April 5, 2021 (Tibetan chants start at 33.33 mins.); Author unknown. (Date unknown). Chronology of the Siege. PBS Frontline. Retrieved April 5, 2021. This was widely reported in U.S. media: Bragg, Roy & Laura E. Keeton. (1993, March 23). Loud wake-up call to cult: Recording of Tibetan chants. The Houston Chronicle, p. A1; Schneider, H. (1993, March 23). Tibetan Chants Are Latest Waco Weapon. The Washington Post. See also: Johnston, David. (1993, July 21). Change at the F.B.I.: Final Act for the F.B.I.’s Director Is Painful and Almost Mute. The New York Times, p. A10; Benson, Eric. (2018). The 25-Year Siege. Texas Monthly, p. 90. A report by the House Committee on Government Reform of the United States Congress says: ‘Director Sessions stated he received a letter from the Dalai Lama about the FBI’s playing of Tibetan chants at the compound during the standoff. The Dalai Lama objected to the playing of the religious chants. The Director said that he replied immediately and ordered that the chants be discontinued.’ United States Congress, House Committee on Government Reform. (2000). The tragedy at Waco: new evidence examined: eleventh report. p. 1011. One of the Dalai Lama’s spokesmen declared later: ‘If the motivation is to create harmony, to provide a peaceful means to conclude this whole fiasco, then that would be appropriate. But the use of chants to create the opposite effect, to antagonize, is very unfortunate.’ Pareles, Jon. (1993, March 28). It’s Got a Beat and You Can Surrender to It. The New York Times, p. 2.

96. The Dalai Lama is the most prominent, best-known member of the largely celibate Geluk sect. Chögyam Trungpa was trained in the Kagyü and Nyingma sects, while Sogyal Lakar’s extended family has a Sakya-Nyingma background. The Kagyü, Sakya, and Nyingma sects are largely non-celibate. However, all Tibetan Buddhist sects have their own cases of abuse. The most recent case to attract widespread media attention is that of Dagri Rinpoché of the Geluk sect, who allegedly involved the Dalai Lama’s private office in his case. Littlefair, Sam. (2019). Prominent Tibetan lama accused of molestation by three women. Lion’s Roar. Retrieved April 3, 2021; Abrahams, Matthew. (2019). Nuns Push for Investigation into Molestation Allegations against Teacher Dagri Rinpoche. Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Retrieved April 3, 2021; FaithTrust Institute. (2020). Summary Report of Sexual Misconduct Complaints Against Dagri Rinpoche. Retrieved March 25, 2021; DemaioNewton, Emily & Karen Jensen. (2020). Buddha Buzz Weekly: Dagri Rinpoche Permanently Removed as FPMT Teacher. Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Retrieved April 3, 2021; Meade Sperry, Rod. (2020). Dagri Rinpoche found to have committed sexual misconduct, FPMT states. Lion’s Roar. Retrieved April 3, 2021. Tenzin Dharpo of the Tibetan website Phayul.com wrote about one of the women who alleged the abuse: ‘In her video posted on YouTube, she said that an apology from Dagri Rinpoche during a meeting set up by the private office of the Dalai Lama, prevented her from reporting the case to police.’ Dharpo, Tenzin. (2020). Dagri Rinpoche committed “intentional and inappropriate sexual behaviour”, says FPMT. Phayul.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021. Dagri Rinpoché was arrested for sexual harassment after a flight from New Delhi to Gagal, India. Allegedly, he groped an Indian woman on board. Indian news sites reported that Dagri Rinpoché told the arresting officers that he worked for the Dalai Lama’s Office in Dharamsala, stating that its address as his residency. For details of the Dagri Rinpoché’s pending criminal case before the Chief Judicial Magistrate, TC Kangra, see the E-Courts Services (CNR number HPKA120015502019). The next hearing date is June 2nd, 2021.

97. This is not an academic issue. In the civil case of 23 ex-adepts’ children against Robert Spatz (also known as ‘Lama Kunzang’) of Ogyen Kunzang Choling (OKC) in Belgium, Spatz maintained that the Dalai Lama’s visit to his center in Brussels, Belgium ‘proved’ that he was a bona fide Tibetan Buddhist teacher in a bona fide Tibetan Buddhist tradition. When Ricardo Mendes, one of those 23 children, met him in Rotterdam in 2018, the Dalai Lama denied knowing Robert Spatz at all, even after he was shown a photograph of himself and Spatz together. For the victims’ and survivors’ reporting on this case, see Author unknown. (Date unknown). #OKCinfo: Exposing OKC/Spatz cult. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

98. For extensive discussions of this matter, see Sparham, Gareth. (1996). Why the Dalai Lama Rejects Shugden. Tibetan Review, 31 (6), pp. 11-13; Dreyfus, Georges B. J. (1998). The Shuk-den Affair: History and Nature of a Quarrel. Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies, 2 (21), pp. 227-270; Batchelor, Stephen. (1998). Letting Daylight into the Magic: The Life and Times of Dorje Shugden. Tricycle: The Buddhist Review, Spring 1998, pp. 60-66; Von Brück, Michael. (2001). Canonicity and Divine Interference: The Tulkus and the Shugden-Controversy. In Charisma and Canon: Essays on the Religious History of the Indian Subcontinent (pp. 328-349). New Delhi: Oxford University Press; Mills, Martin A. (2003). This turbulent priest: contesting religious rights and the state in the Tibetan Shugden controversy. In Richard A. Wilson & Jon P. Mitchell (Eds.), Human Rights in Global Perspective: Anthropological studies of rights, claims and entitlements (pp. 54-70). London: Routledge; Gardner, Alexander. (2013). Treasury of Lives: Dorje Shugden. Tricycle: The Buddhist Review. Retrieved April 3, 2021; Chandler, Jeannine. (2015). Invoking the Dharma Protector: Western Involvement in the Dorje Shugden Controversy. In Scott A. Mitchell & Natalie E.F. Quli (Eds.), Buddhism Beyond Borders: New Perspectives on Buddhism in the United States (pp. 75-91). New York: SUNY Press; Repo, Joona. (2015). Phabongkha Dechen Nyingpo: His Collected Works and the Guru-Deity-Protector Triad. Revue d’Etudes Tibétaines, 33, pp. 5-72. The Association of Geluk Masters, The Geluk International Foundation, & The Association for the Preservation of Geluk Monasticism. (2019). Understanding the Case against Shukden: The History of a Contested Tibetan Practice (Gavin Kilty, Trans.). Somerville: Wisdom Publications.

99. For extended discussions of the Dalai Lama’s distancing attempts, see Finnigan, Mary & Rob Hogendoorn. (2019). Sex and Violence in Tibetan Buddhism: The Rise and Fall of Sogyal Rinpoche. Portland: Jorvik Press; Hogendoorn, Rob. (2020, November 8). The Dalai Lama and Nxivm Revisited. Openbuddhism.org. Retrieved April 3, 2021; Hogendoorn, Rob. (2020, December 5). Knave or Fool? The Dalai Lama and Shōkō Asahara Affair Revisited. Openbuddhism.org. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

100. Ganzevoort, Ruard et al. (Eds.). (2013). Geschonden vertrouwen: Seksueel misbruik in een religieuze context. Tilburg: KSGV. pp. 17-37.

101. Emery, Élodie. (2011). Pas si zen, ces bouddhistes. Marianne, 756, pp. 72-77. Retrieved April 3, 2021; Emery, Élodie. (2017). Violences, abus sexuels. le scandale qui déshonore le bouddhisme. Marianne. pp. 31-32. Retrieved April 3, 2o21. Emery, Élodie. (2017). Scandale chez les bouddhistes: Matthieu Ricard recommande aux disciples plus de vigilance. Marianne. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

102. Ricard, Matthieu. (2017). A point of view. Retrieved March 27, 2021.

103. Gyatso (the fourteenth Dalai Lama), Tenzin. (1999). Ancient Wisdom, Modern World: Ethics for a New Millenium. London: Little, Brown and Company; Gyatso (the fourteenth Dalai Lama), Tenzin. (2011). Beyond Religion: Ethics for a Whole World. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

104. Again, this is not an academic issue. In the OKC civil case in Belgium (see endnote 94), Robert Spatz’s lawyer submitted to the court that Spatz and Matthieu Ricard were once ‘contemporaries,’ that is, fellow students of the same Tibetan teacher, Kangyur Rinpoché. And so, their past proximity was construed as a legal argument underlining Spatz’s authenticity as a bona fide Tibetan Buddhist teacher.

105. Since 1991, the Charter of Tibetans-in-exile promulgates that the Central Tibetan Administration must ‘endeavor to improve the purity and efficiency of academic and monastic communities of monks, nuns, and tantric practitioners, and shall encourage them to maintain proper behavior.’ Right after the Dalai Lama went into exile in April 1959, his Central Tibetan Administration translated the Universal Declaration of Human Rights into Tibetan. It was made a cornerstone of its draft Constitution for Tibet. The Charter that is now in force, likewise, mandates the Central Tibetan Administration to adhere to the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. See article 4 and 17 of: Author unknown. (1991). Charter of the Tibetans in Exile. Retrieved April 3, 2021. Jan-Ulrich Sobisch and Trine Brox discuss challenges in the linguistic and cultural translation of human rights by Tibetans such as the Dalai Lama, as well as his idiosyncratic use of words like ‘religion,’ ‘politics,’ ‘secularism,’ and ‘democracy.’ Sobisch, Jan-Ulrich & Trine Brox. Translations of Human Rights. Tibetan contexts. In Carmen Meinert & Hans-Bernd Zöllner (Eds.), Buddhist Approaches to Human Rights: Dissonances and Resonances (pp. 159-178). Beyond the universality of human rights, Tibetan Buddhist and other spiritual teachers are subject to the criminal and civil codes of the countries they are in, for instance those of India, European countries, or the USA.

106. For an extensive discussion of the concerns Tibetan exiles have expressed over the required vetting of the many people the Dalai Lama meets, see Hogendoorn, Rob. (2020, December 5). Knave or Fool? The Dalai Lama and Shōkō Asahara Affair Revisited. Openbuddhism.org. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

107. Ricardo Mendes, one of the survivors of Robert Spatz and OKC, told the Dutch news network NOS: ‘By attaching his name and reputation to it, the Dalai Lama legitimized OKC.’ For this reason, he wanted to discuss the matter with the Dalai Lama himself. Hogendoorn, Rob. (2020, December 5). Knave or Fool? The Dalai Lama and Shōkō Asahara Affair Revisited. Openbuddhism.org. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

108. Author unknown. (2019). 1966 Land Rover Series IIA 88. RMSothebys.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

109. The German monk Tenzin Peljor (Michael Jäckel, commonly known by the contraction Tenpel) writes: ‘For the Dalai Lama it is first and foremost a religious exercise to see others as fellow human beings. His view is that one must distinguish between the act and the person: compassion for people but rejection of destructive acts. In addition, his actions are based on an understanding of friendship and gratitude that is very different from Western customs and culture: to whoever helped or helps you, like Heinrich Harrer or Jörg Haider, you are grateful and indebted in principle. Friendship is not terminated when some wrongdoings come to light.’ Our translation from Peljor, Tenzin. (2009). Korrekturen und Reflexionen zum Stern-Artikel über den Dalai Lama. Info-buddhismus.de. Retrieved March 30, 2021.

110. Kaufman, Leslie. (2008). Making Their Own Limits in a Spiritual Partnership. The New York Times. Retrieved April 3, 2021; Burleigh, Nina. (2013). Sex and Death on the Road to Nirvana. Rolling Stone. Retrieved April 3, 2021; Schecter, Anna. (2014). My Brief Rendez-vous with the Guru. NBC News. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

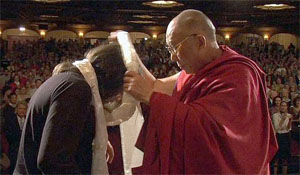

111. The Dalai Lama’s meeting with victims and survivors in Rotterdam, the Netherlands came about thanks to a large group of victims and survivors, as well as the numerous signatories of the petition ‘#MeTooGuru: Support the Dalai Lama’s effort to remedy sexual abuse’—helped by the media attention the petition garnered. The petition is still available online. By April 16, 2021, the petition was signed more than 2,600 times. Full disclosure: to shield the victims and survivors from unwanted attention in (social) media, Rob Hogendoorn acted as their liaison and press contact before, during, and after the Dalai Lama’s visit. Mees, Anna & Bas de Vries. (2018). Misbruikslachtoffers willen dalai lama spreken in Nederland. Nos.nl. Retrieved April 3, 2021; Corder, Mike. (2018). Dalai Lama meets alleged victims of abuse by Buddhist gurus. Associated Press. Retrieved April 3, 2021; Author unknown. (2018). Dalai Lama meets alleged abuse victims. Bbc.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021; Finney, Richard. (2018). Dalai Lama Meets in the Netherlands With Sex Abuse Victims. Retrieved April 3, 2021; Rahim, Zamira. (2018). Dalai Lama says he knew about sexual abuse allegations made against Buddhist teachers. The Independent. Hogendoorn himself reviewed the events in an op-ed published by the Tibetan Review. Hogendoorn, Rob. (2018). The Dalai Lama’s Clarion Call. Tibetan Review. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

112. During their meeting in Rotterdam, the Dalai Lama agreed to the petitioners’ demand that he would ask the Mind & Life Institute to host a meeting on human sexuality, sexual abuse by lay and ordained religious teachers, and sexual trauma. He also agreed to put abuse by lay and ordained Buddhist teachers on the agenda of a gathering of religious leaders and representatives of the major Tibetan schools in Dharamsala in November 2018. After this meeting had been postponed and rescheduled, its single focus became the Dalai Lama’s succession—not sexual abuse. Eckert, Paul. (2017). Tibetan Religious Figures Reject Chinese Role in Dalai Lama Reincarnation. Radio Free Asia. Retrieved April 3, 2021. And so, at the time of writing, the Dalai Lama has yet two deliver on these two promises.

113. Mees, Anna & Bas de Vries. (2018). Dalai lama over misbruik: ik weet het al sinds de jaren 90. Nos.nl. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

114. For the dubious origins and financial history of the Tenzin Gyatso Institute, see Finnigan, Mary & Hogendoorn, Rob. (2019). Sex and Violence in Tibetan Buddhism: The Rise and Fall of Sogyal Rinpoche. Portland: Jorvik Press.

115. Author unknown. (Date unknown). Who Are We? Rigpa.org. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

116. Mostert, Dirk. (2017). Brandpunt: Misbruik in de boeddhistische gemeenschap Hilversum: KRO-NCRV. The documentary can be seen here with English subtitles: Sogyal Truth. (2017). Sogyal Rinpoche & Rigpa – 2017 Documentary – Subtitled in English. YouTube.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

117. For a short version of the DVD included in the second issue of Rigpa’s View Magazine, see Lerab Ling. (2013). The Visit of His Holiness the Dalai Lama to Lerab Ling, August 2008. YouTube.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021. For a previous visit by the Dalai Lama to Lerab Ling in 2000, see Rigpa Videos. (2000). His Holiness the Dalai Lama in Lerab Ling – September 2000. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

118. Sogyal Truth. (2017). Dalai Lama Speaks About Sogyal Rinpoche. YouTube.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021. For the original video, see Gyatso (the fourteenth Dalai Lama), Tenzin. (2017). Inauguration of Seminar on ‘Buddhism in Ladakh.’ YouTube.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

119. After Sogyal Lakar settled the civil case filed by Janice Doe in 1994, the Dalai Lama did admonish Sogyal Lakar to settle down and ‘take a lawful wife.’ But he stood by doing nothing when Sogyal resumed his promiscuous and abusive ‘lifestyle’ as before. And he continued to endorse Sogyal and visit his centers. Finnigan, Mary & Rob Hogendoorn. (2019). Sex and Violence in Tibetan Buddhism: The Rise and Fall of Sogyal Rinpoche. Portland: Jorvik Press. pp. 86-87.

120. See endnote 45. The Dalai Lama is very much a political player. He was one of the few world political figures along with UK Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and US President George H.W. Bush who sided with General Augusto Pinochet of Chile to help keep him from being extradited from England to Spain to stand trial for crimes against humanity. No doubt, much pressure was put on the Dalai Lama to get him to stand for Pinochet’s defense against extradition. Author unknown. (1999). Forgive Pinochet, says Dalai Lama. CBC News. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

121. For a verbatim transcript of the Dalai Lama’s meeting with Keith Raniere and his entourage in Dharamshala, see Hogendoorn, Rob. (2020, November 8). The Dalai Lama and Nxivm Revisited. Openbuddhism.org. Retrieved April 3, 2021. HBO is currently working on a sequel that will cover the trial of Keith Raniere and members of his entourage.

122. Andrews, Suzanna. (2010). The Heiresses and the Cult. Vanity Fair. Retrieved April 3, 2021; Odato, James M. (2010, March 28). Ex-NXIVM official seeks protection. Time Union. Retrieved April 3, 2021; Odato, James M. & Jennifer Gish. (2012, February 12). In Raniere’s shadows. Times Union. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

123. In March 2009, most media reports on Nxivm and Keith Raniere were readily available on the website of The Rick A. Ross Institute Institute and their original sites. Ross, Rick A. (2009). NXIVM: formerly known as Executive Success Programs (ESP): founder Keith Raniere: also linked to “Jness” and Nancy Salzman. Retrieved April 3, 2021. On March 29, 2009 Daniel Weaver wrote an Op-ed column stating that the Dalai Lama’s cancellation of the event ought to be a ‘no-brainer.’ Weaver, Daniel T. (2009, March 29). Op-ed column: Dalai Lama’s visit to Albany sponsored by cult-like group. Daily Gazette. Retrieved April 3, 2021. The same day, Brian Ettkin wrote about the vetting process by the Dalai Lama’s representative Tenzin Dhonden: ‘Mutual friends arranged for Sara Bronfman and Tenzin Dhonden to meet on separate occasions in Sun Valley, Idaho, where she requested an audience with the Dalai Lama, Sara and Tenzin Dhonden said. Bronfman told Tenzin Dhonden that the Dalai Lama might find NXIVM’s tools useful. “She was being very honest,” Tenzin Dhonden said, referring to Sara Bronfman’s disclosures to him during their initial meetings about the negative publicity NXIVM has received. Before granting her an audience, Tenzin Dhonden visited NXIVM’s Colonie headquarters for a week in January 2008 as part of a background check. He observed courses and spoke with coaches and participants, he said, and found them to be “very happy, friendly and sharing.” Tenzin Dhonden said neither he nor anyone else representing the Dalai Lama has actually participated in NXIVM courses. The Bronfmans and Tenzin Dhonden said that news reports, along with the cult researchers’ evaluations of NXIVM programs, were sent to the Dalai Lama’s office in India. Tenzin Dhonden said he’d “briefly” read some newspaper and magazine reports on NXIVM. While he was observing NXIVM training in 2008, he said, he did not interview any former participants or NXIVM critics. “I have my own intellectual resource, capacity, to know persons, to feel persons,” Tenzin Dhonden explained. “I can pick up like that, very easily.”’ Ettkin, Brian. (2009, March 29). Details light on Dalai Lama visit. Times Union. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

124. For an extensive discussion of Tibetans’ concerns about the Dalai Lama’s carefree, high-risk dealings with less than thoroughly vetted characters, see Hogendoorn, Rob. (2020, December 5). Knave or Fool? The Dalai Lama and Shōkō Asahara Affair Revisited. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

125. When The Daily Mail wrote that the Dalai Lama was paid $ 1 million to endorse Nxivm in 2009, the Dalai Lama’s Office was quick to publish a clarification: ‘We wish to categorically state that His Holiness the Dalai Lama never takes an honorarium or fee of any sort, nor does he require that any payment be made to charities or organizations, as a condition of his making a personal appearance. Therefore, the reported allegation has no basis. Neither His Holiness the Dalai Lama nor the Dalai Lama Foundation ever received the alleged $1 million in connection with His Holiness’s appearance in Albany.’ Perry, Ryan. (2018). EXCLUSIVE: Dalai Lama was paid $1 MILLION to endorse women-branding ‘sex cult’ after secret deal between Buddhist’s celibate U.S. emissary and his Seagram billionaire ‘lover’. Dailymail.co.uk. Retrieved April 3, 2021.; Author unknown. (2018, January 25). Clarification in Response to the Daily Mail Story of January 24, 2018. Dalailama.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021. Indy Hack and Frank Parlato responded by validating ‘a source who declared that the Bronfmans offered the Dalai Lama one million to speak for NXIVM and that it was her impression that there was never any concern about his or one of his organizations accepting it.’ Hack, Indy & Frank Parlato. (2018). Further questions about the Dalai Lama’s Million Dollar Visit to NXIVM Sex Cult. Frankparlato.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

126. The sisters’ father, Edgar Bronfman Sr. passed away in 2013. Kandell, Jonathan. (2013, December 22). Edgar M. Bronfman, Who Built a Bigger, More Elegant Seagram, Dies at 84. The New York Times. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

127. Sogyal did name his center in Berne, New York, the Tenzin Gyatso Institute, after the 14th Dalai Lama. But Sogyal’s devotees always maintained control of its governance and finances. Finnigan, Mary & Rob Hogendoorn. (2019). Sex and Violence in Tibetan Buddhism: The Rise and Fall of Sogyal Rinpoche. Portland: Jorvik Press. pp. 141-144.

128. •

129. Author unknown. (Date unknown). Lost Horizon (1937) Imdb.com. Retrieved April 16, 2021. The movie is based on the fantasy novel Lost Horizon by the British author James Hilton. Hilton, James. (1933). Lost Horizon. London: Macmillan & Co.

130. The problem with the western people creating and then naturally buying this myth is just that, it is a myth. The Dalai Lama is, however, the delegated spokesman for Tibet and Tibetan Buddhism. Because of his social position he has legitimate access to the language of the institution. His words are not only his—he is also a carrier of the words of the institution and as such, represents the authority of Tibetan Buddhism. He is the authorized spokesperson, the delegated representative whose words and speech concentrates within it the accumulated symbolic capital of the institution—pure, unadulterated Tibetan Buddhism. It has delegated him as its authorized representative, to be an object of guaranteed belief, certified as correct—that is, both right and just.128Bourdieu, Pierre. (1991). Language and Symbolic Power (Edited and Introduced by John Thompson, translated by Gino Raymond and Matthew Adamson). Cambridge: Harvard University Press. pp. 107-116. The two chapters ‘Authorized Language: The Social Conditions for the Effectiveness of Ritual Discourse’ (pp. 107-116) and ‘Rites of Institution’ (pp. 117-126) explain well the power of institutions as manifest through their delegated representatives.

131. Many Tibetan Buddhist centers and monasteries in the West reserve a dedicated room for the Dalai Lama’s use only, should he desire to sojourn there at any given time.

132. See Chapter V (‘Of Executive Government’) of the Constitution of Tibet promulgated by the Dalai Lama in 1963, and article 31 of the Charter of Tibetans-in-exile promulgated by The Eleventh Assembly of Tibetan People’s Deputies in 1991. Author unknown. (1963). Constitution of Tibet: Promulgated by His Holiness the Dalai Lama: March 10, 1963; Autor unknown. (1991). Charter of the Tibetans in Exile; Gyatso (the fourteenth Dalai Lama), Tenzin. (1992). Guidelines for future Tibet’s polity and the basic features of its constitution. Tibetan Review, 27 (10), pp. 10-14.

133. See endnote 21 and 22. See also: Gyatso (the fourteenth Dalai Lama), Tenzin. (2011). Statement of His Holiness the Dalai Lama on the 52nd Anniversary of the Tibetan National Uprising Day. Dalailama.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021; Gyatso (the fourteenth Dalai Lama), Tenzin. (2011). Message of His Holiness the Dalai Lama to the Fourteenth Assembly of the Tibetan People’s Deputies. Dalailama.com. Retrieved April 3, 2021; Gyatso (the fourteenth Dalai Lama), Tenzin. (2011). His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s Remarks on Retirement – March 19th, 2011. Retrieved April 3, 2021. In the documentary The Great 14th, the Dalai Lama says that the Dalai Lama institution should return to the position of the 1st through 4th Dalai Lamas: ‘only spiritual leader, no political power.’ Rawcliffe, Rosemary. (2020). The Great 14th. Retrieved April 15, 2021.

134. The Dalai Lama told Pico Iyer that when he first met Shōkō Asahara, ‘he was genuinely moved by the man’s seeming devotion to the Buddha: Tears would come into the Japanese teacher’s eyes when he spoke of Buddha. But to endorse Asahara, as he did, was, the Dalai Lama quickly says, “a mistake. Due to ignorance! So, this proves” (and he breaks into his full-throated laugh), “I’m not a ‘Living Buddha!'”‘ Iyer, Pico. (2004). Sun After Dark: Flights Into The Foreign. In Making Kindness into Reason (Kindle Edition ed., pp. 51-78). New York: Vintage Departures; Iyer, Pico. (2008). The Open Road: The Global Journey of the Fourteenth Dalai Lama. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 107.

135. Hitchens, Christopher. (1998, July 13th). His Material Highness. Salon. Retrieved April 3, 2021.

About the author: Stuart Lachs & Rob Hogendoorn

Stuart Lachs (b. 1940) is an independent scholar and long-time Ch'an/Zen practitioner. Investigative reporter and academic researcher Rob Hogendoorn (b. 1964) began researching the reception of Buddhism in Western society and culture in the early 1990s. His modus operandi remained the same ever since: independent, inquisitive and provocative.