The Mahasiddha and His Idiot Servant [EXCERPT]

by John Riley Perks [John Andrews]

© 2004 by John Riley Perks

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

My mother was a Wicca spiritual healer and practical nurse. My grandmother, who was a nurse physician, would take my mother along on her rounds. One of the stories my mother liked to tell of her childhood travels with my grandmother was about the death of Freedom. Freedom was the first name of an old woman of the village who lived in a cottage where the animals still lived in the bottom half of the house, providing winter heat for the humans who lived upstairs. Word had come that Freedom was dying and my grandmother and mother went to the house where the old woman now lived alone with a cow. They climbed the ladder and found Freedom lying on her straw-mattress bed, her breathing shallow and her consciousness coming and going. My grandmother told my mother to stay with Freedom and to lay her out after she died. This entailed plugging her anus and vagina with cotton and tying closed her mouth. Then my grandmother left to visit another patient.

It was night and although it was not my mother's first experience with death, it was her first time of being alone with a dying person. She was terrified. The wind blew out the kerosene lamp. My mother clung to Freedom's hand, asking and praying for her not to die before my grandmother returned. The cow below made sounds like demons ascending the ladder and with the labored breathing and twitching of Freedom, the screeching of owls, the yelling of night hawks, and the house moving in the night wind, my mother was near to fainting.

It was at least two hours before my grandmother returned to find my frightened mother still grasping Freedom's hand. Lighting the lamp and inspecting Freedom, my grandmother exclaimed in a sharp tone, "Dolly, Freedom is dead. Go and get the Vicar's dining room table leaf and we will lay her out." I can always see my mother as a fourteen-year-old girl terrified and beset by spirits, yet crossing the village alone at night to return with the table leaf under her arm to lay out the dead Freedom. It was this story and her act of bravery that always inspired me to go beyond my fears. Even at an early age I admired her willingness to tell me this story, not only of her bravery, but of her fears in handling the beings and spirits that surrounded her.

***

I had decided to make a sacred object out of Rinpoche. In order to do that I would be very formal in a British way. Now Max, who was more laid-back, California-style, would greet Rinpoche in the morning by saying, "Hi, Rinpoche, I suppose you want breakfast." Max would not even get up out of his chair, but would continue to read the newspaper. This pissed the hell out of me. The more formally British I got, the more relaxed Max seemed to get.

This got to the point where I really wanted to throttle Max for not behaving correctly as I thought he should, and I told Rinpoche I was ready to knock some sense into him.

"Well, we can't do that," he said. "Let's play some tricks on him."

Max was a speed freak whenever he got up, whether it was morning or evening. He would throw on his kimono and jump into his slippers, which he kept outside his bedroom door. He would just slide his feet into the slippers and take off down the hall. One night Rinpoche sent the grateful Max off to bed early.

"You look tired, Max; better go to bed," he said.

We waited about an hour or two and then we went upstairs and securely glued Max's slippers to the floor. Rinpoche was rolling around stifling his laughter. The next morning we were up before Max, sitting in the kitchen having tea. The kitchen was right under Max's room. We heard him get up, rush out his door, and then, bang! He hit hard on the upstairs floor. Down he came to the kitchen.

"Say, Rinpoche," he exclaimed, "someone glued my slippers to the floor." I burst out laughing.

Rinpoche looked at him and said, "Perhaps it was an illusion." Then he started to chuckle.

The following week was passing in an unusually quiet and peaceful manner when Rinpoche said to me, "Johnny, can you put something that will smell in Max's room."

"You mean like scent, Sir?" I asked, not really understanding his intent.

"No, no," he looked at me like I was crazy. "Something that will stink."

We were eating fish, so I said, "Well, Sir, I could nail a piece of fish up under his bed."

"Great," he said, nodding his head.

So I put a large piece of halibut into a net bag and nailed it to the underside of Max's bed. When I opened my bedroom door the next morning the entire hallway smelled like Fulton's fish market. Max said nothing and both Rinpoche and I were quite surprised. We thought that he must have twigged it but the next day the whole house smelled of rotten fish. Max dame downstairs and said, "John, I think there is a dead mouse in the wall in my room. Could you take a look? I'm going to move to another room."

That same day, believe it or not, I found a dead mouse on the lawn. As Max was moving over to the new room I went upstairs and chipped away at part of the wall and pretended to find the dead mouse.

After Max moved everything into his new room, I nailed the dead fish to the bottom of his new bed. When Max complained about the smell again, Rinpoche said, "Your smell must be following you around."

I had always been a hunter. It was part of my self-sufficient trip of taking care of myself in the wilderness -- not just of the forest but of the world. Now that I was a Buddhist I reacted in horror to killing, although playing with guns for purely self-defense was something I was sure that the Buddha would have agreed with. In any case, hunting seemed more humane than a slaughterhouse.

When I was a young farmhand I had never been to a state-registered slaughterhouse. I had no more idea of the procedure than did the black-and-white cow we were taking there. The inside was stainless steel and white tile with a cement floor. An electric hoist with a hook on it ran down the center of the room. The place reeked of Pine-Sol. The smell made the atmosphere even more surrealistic. We had to coerce the cow into the room by twisting her tail. She was wide-eyed with terror. One of the fellows attached chain cuffs to her rear legs and ran the chain up the hook on the electric hoist. He pressed the red button on the wall and the hoist slowly gathered in the chain and lifted the animal. The cow's body hung in the air only inches above the floor. A pair of pliers attached to a rope was put into the cow's flaring nostrils. I was told to pull the rope so that the cow's neck was stretch tight. The other fellow took a large butcher's knife and with a swift swing he struck the cow's stretched neck. The cow's blood burst out across the room with great force. I was so shocked I let go of the rope. The head of the cow was only half severed. The cow, swinging slightly, convulsed while it hung suspended in the center of the room. Blood spewed out of her severed neck in all directions. Her mouth opened and closed in silent bellows as air rushed in and out of her exposed windpipe.

One of the fellows, enjoying my shock, took a cup and filled it with blood from the cow's streaming jugular vein. He offered the steaming cup to me. "Want some? It puts lead in your pencil." Now, thoroughly amused by my repulsion, he laughed loudly and drank the hot blood, leaving red stains on his lips. Within an hour the cow was skinned, disemboweled, cut into sections, and hung in the cooler. I decided I liked hunting -- it was more romantic.

In order to be a successful hunter you had to first understand and appreciate the hunted animal. You had to know its lifestyle, its nature, its habitat. You had to actually enter its world. You had to realize that like yourself, an animal and its world are alive, and that life and death, being alive, have a quality of magic -- a sacredness.

I had a holy concept of sacredness, regarding some things as holy and others as untouchable. My shrine in my Buddhist practice was like something out of House & Garden magazine -- flowers, candles and incense, and beautiful Tibetan pictures. I was on my way to becoming a real holy man.

Rinpoche could see my progress in practicing Buddhism and he started to bother me about hunting. He wanted me to take him hunting. "I want to kill something," he said. "I have never killed anything. I've just been a Buddhist monk all my life."

I would always refuse. "It would not be right for you to kill something, Sir."

Seeing Rinpoche in a slaughterhouse or even hunting didn't seem right to me. It didn't fit my concept of a holy man. The hunting queries continued for some time until one morning a flock of snowbirds gathered on the frozen lawn where I had thrown some old bread. Rinpoche picked up the .22 rifle from the kitchen corner. He walked toward the window and said, "Right, Johnny? We're going to shoot some birds."

I protested. "Sir, we've been through this a mission times. Please hand me back the gun."

Rinpoche, always one to enjoy himself, began to leap around the room in his kimono singing, "I'm going to kill. I'm going to kill." I didn't like the way it sounded at all. I took the gun from him and loaded it. But I also moved the rear sight out of line. I opened the kitchen window.

"Here you are, Sir," I said as I handed the gun to Rinpoche. "It's all ready to fire."

Rinpoche took aim at the birds and fired the single-shot rifle into the morning air. The birds flew off and not one was left dead. I threw more bread out and Rinpoche fired and again no birds were killed. We both laughed. I wasn't surprised, as he probably couldn't have hit the barn with those readjusted sights.

Rinpoche looked directly at me and said, "Oh, you're just an English gentleman, you couldn't kill a bird either." It was a challenge and I took the bait.

"Oh?" I said, accepting the wager.

So I took the gun and aimed, using only the front sights on the rifle and picturing the rear sights in my mind. I killed a bird, much to my own delight and Rinpoche's surprise. I walked out, picked up the bird's carcass, and wave it to Rinpoche and Max.

As I helped Rinpoche up the stairs to bed that night he said, "Johnny, do you know what killing that bird means?

"No, Sir," I said.

"It means you will get married and your first child will be a boy will be a tulku. Also it will cause a slight interruption in our living situation.

I was dumbfounded. I had no idea what relationship there was between the events of that morning and my having a son. Rinpoche didn't expand on it, so I let it go and silently put him to bed.

Two days later Rinpoche and Max were in town shopping and got stuck in a heavy snowstorm. They had to stay overnight at an inn. Rinpoche called and told me with a chuckle, "We've been held up by a snowbird." A slight interruption. Interestingly, I have not killed anything since. Later I did get married and our first child was a daughter whom we called Sophie. Rinpoche announced that she was a reincarnation of G.I. Gurdjieff.

"But Gurdjieff was a man," I said.

"Yes," said Rinpoche, "that's Gurdjieff's joke on us."

***

Somehow during this winter of the retreat year my handle on what I thought of as reality was becoming a little insecure. Out of seemingly nowhere I started having panic attacks, rapid heartbeat, and hyperventilation. I was sure I was going to die on the spot and I was certain there was a ghost following me around the house. So I asked Rinpoche if he had seen any ghosts in the house.

"Only two," he replied.

I almost fainted.

One night I had a dream of talking to a woman in her late thirties. She was wearing a long dress and holding my outstretched hand. She was talking about building the farmhouse where we were staying. "When were you born?" I asked.

"May, 1853," she said.

I did the math in my dreaming mind, pulled my hand away and sat up in the bed, awake, with my heart racing.

When I was physically with Rinpoche I did not have panic attacks but I was certain that he was somehow the cause of it all. It did not occur to me that Buddha's message, "Nothing whatsoever should be clung to," applied to me. My Britishness was part of "me." I had made my living by being British and if I gave that up what would I become? American, French, Italian? I mean, you can't just become nothing. But the fear was growing in me that Rinpoche was somehow nothing -- a gap. How could "I" act as nothing? Where do you start? After all, the Path of Accumulation was the Path of Accumulating, not the Path of Nothingness. The Path of Accumulation meant that I was going to get something. Here I was being invited to jump into empty nothingness. Not even invited, I was being pushed -- caught between a rock and a hard place. My memories of war became a welcome and safe distraction. I felt that if I could keep these away from Rinpoche I could hang on to some semblance of sanity. Every time the world would start melting around him I would take refuge in the only thing left in my thinking mind, my memories.

Rinpoche said he would like to target shoot. I had my .38 revolver, which I had purchased to protect Rinpoche (some joke), and a .22-caliber single-shot rifle. Now I went out and purchased a ruger .223-caliber semiautomatic with a thirty-round clip. I set up a target area in the garden that resembled World War II in miniature, with plastic soldiers, tanks, and trucks. Rinpoche, Max, and I would go out and blast them. Rinpoche called them the Mara Army. "You could be victorious over the troops of Mara, Johnny," he said. That sounded good but what the hell did it mean? I looked up Mara in the encyclopedia and it said "Mara is the Lord of the Sixth Heaven of the Desire Realm and is often depicted with a hundred arms and riding on an elephant."

Oh, I thought, mythology. I felt better. It's not real. But just in case, I started to look for an elephant rifle. Perhaps a Winchester .375 H and H Magnum might do the trick.

One evening Rinpoche and I were sitting in the kitchen. Max rushed in from shopping in town. Now, the closet and basement doors were next to each other and both doors looked the same. The basement stairs were very steep and ran down about twelve feet. Max was distractedly talking to us as he took off his coat, opened the wrong door, and, not looking, reached in to hang it up. Rinpoche yelled, "Shunyata," as Max and his coat fell into the basement. Unhurt except for a few scrapes, Max climbed out.

"Rinpoche," said Max, "You should have yelled to stop me."

"Why?" replied Rinpoche. "You could have gotten enlightened."

That night we went out to dinner at the local inn. Rinpoche had me purchase some cigars and secretly put some gunpowder in one of them for Max. the three of us sat in the inn causally smoking our stogies, two of us waiting in anticipation for the other one to explode. This went on for some time until Max, with the cigar still in his mouth, took a big puff and the cigar let out a big whoosh rather than an explosion. Flaming sparks and smoke shot out across the room from the cigar. Max remained pretty cool and said, "Your idea, I expect, Rinpoche." The three of us laughed.

However, the truth was that Max was a nervous wreck, and beneath my dignified British facade so was I. Finally, Max asked Rinpoche if he could go back to Boulder for a few weeks. Rinpoche gave his okay and Max departed, leaving Rinpoche and me alone in a house surrounded by deep snow. By necessity Max left his dog, Myson, with us. One night after supper Rinpoche said, "Get Myson and bring him in here." I dragged the shaking dog into the kitchen and following Rinpoche's instructions I sat him on the floor and covered his eyes with a blindfold. I set up stands with lighted candles by either side of his head. Myson couldn't move his head without being burned. Rinpoche took a potato and hit Myson on the head with it. When the dog moved, the fur on his ear would catch on fire. I put out the flames. Now and then Rinpoche would scrape his chair across the tiled floor and whack him again on the head with a potato.

"Sir," I began hesitantly, trying to stop him.

"Shut up," snapped Rinpoche, "and hand me another potato."

I started to empathize with the dog. In fact, I became the dog. I was blindfolded and was banged on the head with a spud and if I turned my head my hears would burn and there was the squealing sound of the chair on the floor. Pissing in my pants I was that dog not being able to move, feeling terrified and at the same time excited. Finally, the scraping chair and the potato throwing stopped and we released the shaking dog, who ran upstairs to Max's empty room.

"That's how you train students," Rinpoche calmly stated to me.

"Jesus," I thought, "that's pretty barbaric."

Rinpoche had me change the telephone number so that Max could not call us before he came back. He arrived, bags in hand, concerned that he had not been able to reach us. Before he could say much else, Myson rushed in and jumped all over him in exuberant delight. Rinpoche deliberately scraped the kitchen chair across the tiled floor. The terrified dog shot out of the house and fled across the field. Max was shocked and pointedly asked, "Rinpoche, what did you do to my dog?"

"I don't see any dog," he replied, looking at me.

"I got it!" I said, with the realization of being blindfolded and having three things happen to you at once, knowing the scraping and the disappearance of the dog were both somehow illusion. In fact, it was all illusion. Everything was illusion, but real. Rinpoche smiled and warmly greeted Max.

Did I get it? Not then.

“It was summer of 1985. I "married" Rinpoche on June 12th of that year. I met him around May 31st at a wedding of Jackie Rushforth and Bakes Mitchell in the back yard of Marlow and Michael Root's home. That year, we had our wedding at RMDC a few days before Assembly, then we had Seminary and Encampment happened during Seminary.

That was the year he spoke of limited bloodshed and taking over the city of Halifax and the Provence of Nova Scotia. We were in the middle of the Mahayana portion of seminary teachings. For weeks, CTR (Chögyam Trungpa Rinpoche) had been asking everyone he saw if they had seen a cat. He asked the head cook, the shrine master, and all of his servants if they'd seen one. We returned to our cabin late one night after a talk and there was this beautiful tabby cat sitting on the porch. I said, "Here kitty, kitty" and it came right over to me, purring and rubbing against my legs. I picked it up and said: "Here, Sweetie. Here's the cat you've been wanting."

I can't remember exactly which guard was on duty, but I think it was Jim Gimian, and of course Mitchell Levy. Someone took the cat from me and Rinpoche ordered them to tie him to the table on the porch. He instructed them to make a tight noose out of a rope so the cat didn't get away. He stood over his guards to examine the knots and make sure they were secure. I was curious at this point, wondering what this enlightened master had in mind for the cat. I knew there were serious rodent problems on the land and I assumed he wanted to use the cat for this problem.

Then, he instructed the guard to bring him some logs from the fire pit that was in front of the porch, down a slight slope. We took our seats. Rinpoche was seated to my right and there was a table between us for his drinks. He ordered a sake. The logs were on his right side, so he could use his good arm. (His left side was paralyzed due to a car accident that happened in his late twenties.)

The cat was still tied by a noose to the table. Rinpoche picked up a log and hurled it at the cat, which jumped off the table and hung from the noose. It was making a terrible gurgling sound. He finally got some footing on the edge of the deck and made it back onto the porch. Rinpoche hurled another log, making contact and the cat let out a horrible scream as the air was knocked out of him.

I said: "Sweetie, stop! What are you doing? Why are you doing this?" He said something about hating cats because they played with their food and didn't cry at the Buddha’s funeral. He continued to torture the poor animal. I was crying and begging him to stop.

I said, "I gave you the cat. Please stop it!" I'll never forget his response. He looked at me and said: "You are responsible for this karma" and he giggled. I got up to try and stop him and he firmly told me to sit down. One of the guards stepped closer to me and stood in a threatening manner to keep me in my place.

The torture went on for what seemed like hours, until finally the poor cat made a run for his life with the patio table bouncing after him. It was clear he had a broken back leg. I'm sure that cat died. I looked for him or the table for the rest of Seminary and never found either. I imagined him fleeing up the mountain and the table catching on something and strangling him.

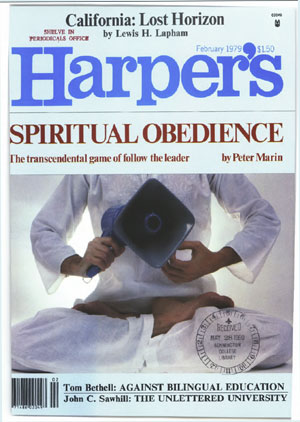

I was completely traumatized by the event, but it was never spoken of again. Rinpoche told me the "karma" from this event was good. I was dumbfounded. A common feeling I had when around Rinpoche was that there were things going on that I simply could not understand. It seemed like other people, with a knowing nod of their heads, understood things on a deeper level than I. I was in fear of exposing my ignorance, so i learned not to question and to go with the crowd around him. They didn't appear to have any problems with what he did. Such was the depth of their devotion. I just needed to generate more devotion to Rinpoche and one day I might understand.”

-- by Leslie Hays

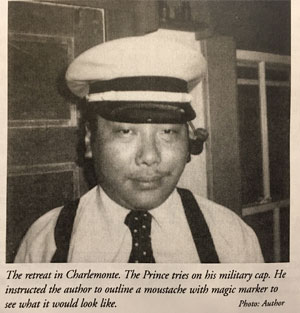

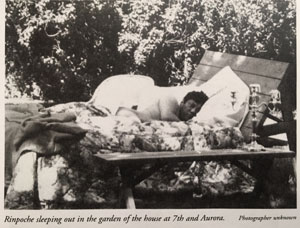

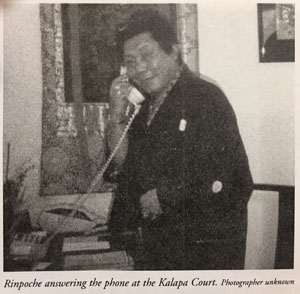

It was during this retreat in Massachusetts that Rinpoche started envisioning a developing the Kingdom of Shambhala. The Kalapa Court would be Rinpoche's home and it was to be in my charge. Instead of being Rinpoche's butler I would soon be Master of the House. I would become a Dapon in charge of the Court Kusung, or servant guards -- in Buddhist terms, Bodhisattva Guardians. Molly, one of Rinpoche's students, came down from Karme Choling. She was an illustration artist and she and Rinpoche together designed the Shambhala flag -- a white ground with blue, red, white, and orange stripes on the leading edge and the yellow sun in the white field. Rinpoche designed and drew the Shambhala arms of the tiger, lion, garuda, and dragon, which are soon on the cover of Shambhala: The Sacred Path of the Warrior (published by Shambhala Publications, Inc., 1984)

I was excited about this creative time. This was going to be a real kingdom with its location in Nova Scotia, Canada. I would be safe within that reality, or so I thought. One day Rinpoche said to me, "Well, you know, Johnny, someone has to ask me."

"Ask you what?" I said.

"Ask me to become Earth Holder, the Monarch of Shambhala."

"Well, I'll ask you," I replied.

"Great!" said Rinpoche. We planed the event for the Tibetan New Year. I cut a tree for a flagpole and Max planned a dinner. Then at sunrise on the New Year the three of us got up and dressed in our best attire. As the sun rose in the eastern sky I asked Rinpoche formally if he would become Sakyong for the benefit of all beings.

He replied, "Yes."

I fired off a twenty-one shot salute from my pistol and Max ran the Shambhala flag up the pole. We saluted and shouted "Hip, hip, hurray!" then followed up by singing the Shambhala anthem. Max and I went into the dining room and feasted with the new Sakyong. I was joyful and excited, but underneath, my uneasiness continued to alternately swell and subside. Somehow the reality of the "gap" was still lurking below my world of this-and-that. On an intellectual level that was still fairly primitive I had some understanding of Buddhism. I knew what it was supposed to look like -- peaceful, calm, wise, compassionate. I knew enough to say, "Yes, I got it," but at the same time it was not in my gut on a visceral level. I thought perhaps I should do a retreat, since it would give me a change to get away, relax, and get myself together before things went too far.

I could see myself robed, sitting under a pine tree in meditation posture with the sunlight playing on my shoulders and the wind in the pines. "Yes, that's it," I concluded, so I asked Rinpoche.

"Not a chance," he growled.

"But, Sir, I could finish my prostrations and do the other practices ... take the Vajrayogini abhisheka with David and the Regent and ..."

"No hope of that," he snapped.

Shit. I was trapped again, stuck in the life of a servant bursting with resentment. Then he gave me one of those smiles that light up the whole dark universe. It penetrated into my murk and dissolved it and I was better and worse off simultaneously.

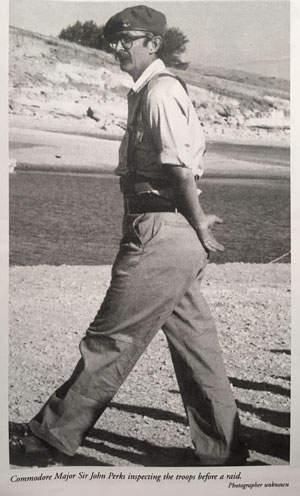

"One day you will be Sir John Perks," he said.

Wow, I thought. Sir John Perks of the Kingdom of Shambhala. I was full of hope again.

Aloneness, when it hit, ruined my hopes and expectations. I was walking to the car in Greenfield, having done the shopping, when it struck. I was suddenly overwhelmed with a sense of total aloneness and stopped dead in my tracks. There was no John Perks. There was nothing to be alone. Had "nothing" been a mental concept, it would have been something to hold onto. Then I panicked.

Only now, looking back, can I say that it was an overwhelming realization of nonexistence. The only way that I can convey what the experience was like is to ask the reader to imagine that all you think you are is totally fabricated. What you are is totally manipulated and conditioned by your own mind. Had I completely realized this at the time I would have died on the spot from a heart attack. For what was under assault was my thinking mind, its solid reality, what and who I thought I was. That which I thought was reality was, in fact, totally empty. This was the great "switcheroo," or turnaround.

Desperately trying to get back to what I still thought was my solidity I staggered to the car, trying not to hyperventilate. I managed to drive to the Howard Johnson's Motel bar. I ordered a double gin and tonic and drank it down like a glass of water.

"Are you okay?" asked the bartender. Where had I heard that phrase before?

"Fine, fine," I said and ordered another double. Sir John Perks had better get a suit of armor, I thought wryly.

But the attacks became more frequent. Then I had a realization. Sex! If I felt so alone why not have a partner? I asked Rinpoche if I could have a lady friend up on some weekends. To my surprise he said yes. So I invited a friend from Boston to visit. But it gave me no relief. In fact, it made the aloneness sharper and I felt as if I were going to die any second. One day at breakfast Rinpoche said to me, "Johnny, isn't it strange how orgasm and death feel the same?"

I blocked his words for the moment and panicked later.

Relief came several days later when he said, "Johnny, let's take a trip to London."

I pretended not to be excited, and to make sure, I asked, "To London, England, Sir?"

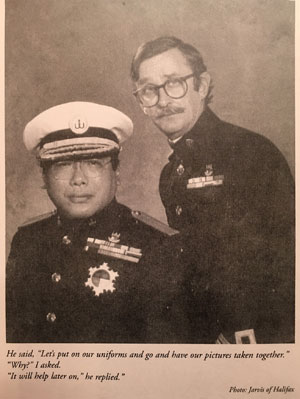

"Yes," he answered matter-of-factly. "We need to get some Shambhala medals made there and we could get some military uniforms." I brightened up. Trooping of the Colors meets sir John Perks. I had a mission.

"Let's stay at the Winston Churchill Hotel," he suggested.

National pride swelled in my chest. Shambhala was going to be British after all. As a safety procedure I went to the local doctor and got prescriptions of Librium and Tagamet for my panic and stomach pain. Sam, the publisher of Shambhala publications, was to meet us in London where he had an office. On the aircraft Rinpoche and I sat together. He was quite upbeat and talked about all the things we would do in London: restaurants, nightclubs, theater, and clothing stores. The air stewardess asked what we would like to drink. Rinpoche ordered his usual. "Ginandtonicus," pronounced as the name of the Roman general from the Asterisk Comic Books.

"You could teach people etiquette, Johnny," said Rinpoche. He went on talking about military uniforms, tuxedos, evening dress, balls, dancing, and formal dinners. Excitedly I joined in with further ideas. Rinpoche said, "Yes! Yes! Yes! Let's do it. We will grow old together." Bliss and joy returned, drowning out the emptiness.

And so it came to pass. In London we stayed at the Winston Churchill. We took the designs of the Shambhala medals to the jewelers to be made. We ordered uniforms at Grieves and Hawks on Savile Row -- a general's uniform for Rinpoche, a major's uniform for me. Rinpoche used his family name on the order form, Mr. C.T. Mukpo. I used my original birth name, John Andrews. The clerk looked at Rinpoche's form in a quizzical way and asked, "Who is Mr. C.T. Mukpo?"

I hesitated, my mind searching for a realistic answer. Finally I said the first true thing I had ever said in my life.

"I have absolutely no idea."

), but the sun is below and tries to draw you down. But you draw a line above the below and long for the above and are completely at one. There the serpent comes and wants to drink from the vessel of the below. But there comes the upper cone and stops. Like the serpent, the looking coils back and moves forward again and afterward you very much (--) long to return. But the lower sun pulls and thus you become balanced again. But soon you fall backward, since the one has reached out toward the upper sun. The other does not want this and so you fall asunder, and therefore you must bind yourselves together three times. Then you stand upright again and you hold both suns before you, as if they were your eyes, the light of the above and the below before you and you stretch your arms out toward it, and you come together to become one and must separate the two suns and you long to return a little to the lower and reach out toward the upper. But the lower cone has swallowed the upper cone into itself, because the suns were so close. Therefore you place the upper cone back up again, and because the lower is then no longer there, you want to draw it up again and have a profound longing for the lower cone, while it is empty Above, since the sun Above the line is invisible. Because you have longed to return downward for so long, the upper cone comes down and tries to capture the invisible lower sun within itself. There the serpent's way goes at the very top, you are split and everything below is beneath the ground. You long to be further above, but the lower longing already comes crawling like a serpent, and you build a prison over her. But there the lower comes up, you long to be at the very bottom and the two suns suddenly reappear, close together. You long for this and come to be imprisoned. Then the one is defiant and the other longs for the below. The prison opens, the one longs even more to be below, but the defiant one longs for the above and is no longer defiant, but longs for what is to come. And thus it comes to pass: the sun rises at the bottom, but it is imprisoned and above three nest boxes are made for you two and the upper sun, which you expect, because you have imprisoned the lower one. But now the upper cone comes down powerfully and divides you and swallows the lower cone. This is impossible. Therefore you place the cones tip to tip and curl up toward the front in the center. Because that's no way to leave matters! So it has to happen otherwise. The one attempts to reach upward, the other downward; you must strive to do this, since if the tips of the cones meet, they can hardly be separated anymore --therefore I have placed the hard seed in-between. Tip to tip -- that would be too beautifully regular. This pleases father and mother, but where does that leave me? And my seed? Therefore a quick change of plan! One makes a bridge between you both, imprisons the lower sun again, the one longs for the above and the below, but the other longs especially strongly for the forward, above and below. Thus the future can become -- see, how well I can already say it -- yes, indeed, I am clever -- cleverer than you -- since you have taken matters in hand so well, you also get everything beneath the roof and into the house, the serpent, and the two suns. That is always most amusing. But you are separated and because you have drawn the line above, the serpent and the suns are too far below. This happens because beforehand you curled around yourself from below. But you come together and into agreement and stand upright, because it is good and amusing and fine and you say: thus shall it remain. But down comes the upper cone, because it felt dissatisfied, that you had set a limit above beforehand. The upper cone reaches out immediately for its sun -- but there is nowhere a sun to be found anymore and the serpent also jumps up, to catch the suns. You fall over, and one of you is eaten by the lower cone. With the help of the upper cone you get him out and in return you give the lower cone its sun and the upper cone its as well. You spread yourself out like the one-eyed, who wanders in heaven and hold the cones beneath you -- but in the end matters still go awry. You leave the cones and the suns to go and stand side by side and still do not want the same.

), but the sun is below and tries to draw you down. But you draw a line above the below and long for the above and are completely at one. There the serpent comes and wants to drink from the vessel of the below. But there comes the upper cone and stops. Like the serpent, the looking coils back and moves forward again and afterward you very much (--) long to return. But the lower sun pulls and thus you become balanced again. But soon you fall backward, since the one has reached out toward the upper sun. The other does not want this and so you fall asunder, and therefore you must bind yourselves together three times. Then you stand upright again and you hold both suns before you, as if they were your eyes, the light of the above and the below before you and you stretch your arms out toward it, and you come together to become one and must separate the two suns and you long to return a little to the lower and reach out toward the upper. But the lower cone has swallowed the upper cone into itself, because the suns were so close. Therefore you place the upper cone back up again, and because the lower is then no longer there, you want to draw it up again and have a profound longing for the lower cone, while it is empty Above, since the sun Above the line is invisible. Because you have longed to return downward for so long, the upper cone comes down and tries to capture the invisible lower sun within itself. There the serpent's way goes at the very top, you are split and everything below is beneath the ground. You long to be further above, but the lower longing already comes crawling like a serpent, and you build a prison over her. But there the lower comes up, you long to be at the very bottom and the two suns suddenly reappear, close together. You long for this and come to be imprisoned. Then the one is defiant and the other longs for the below. The prison opens, the one longs even more to be below, but the defiant one longs for the above and is no longer defiant, but longs for what is to come. And thus it comes to pass: the sun rises at the bottom, but it is imprisoned and above three nest boxes are made for you two and the upper sun, which you expect, because you have imprisoned the lower one. But now the upper cone comes down powerfully and divides you and swallows the lower cone. This is impossible. Therefore you place the cones tip to tip and curl up toward the front in the center. Because that's no way to leave matters! So it has to happen otherwise. The one attempts to reach upward, the other downward; you must strive to do this, since if the tips of the cones meet, they can hardly be separated anymore --therefore I have placed the hard seed in-between. Tip to tip -- that would be too beautifully regular. This pleases father and mother, but where does that leave me? And my seed? Therefore a quick change of plan! One makes a bridge between you both, imprisons the lower sun again, the one longs for the above and the below, but the other longs especially strongly for the forward, above and below. Thus the future can become -- see, how well I can already say it -- yes, indeed, I am clever -- cleverer than you -- since you have taken matters in hand so well, you also get everything beneath the roof and into the house, the serpent, and the two suns. That is always most amusing. But you are separated and because you have drawn the line above, the serpent and the suns are too far below. This happens because beforehand you curled around yourself from below. But you come together and into agreement and stand upright, because it is good and amusing and fine and you say: thus shall it remain. But down comes the upper cone, because it felt dissatisfied, that you had set a limit above beforehand. The upper cone reaches out immediately for its sun -- but there is nowhere a sun to be found anymore and the serpent also jumps up, to catch the suns. You fall over, and one of you is eaten by the lower cone. With the help of the upper cone you get him out and in return you give the lower cone its sun and the upper cone its as well. You spread yourself out like the one-eyed, who wanders in heaven and hold the cones beneath you -- but in the end matters still go awry. You leave the cones and the suns to go and stand side by side and still do not want the same.