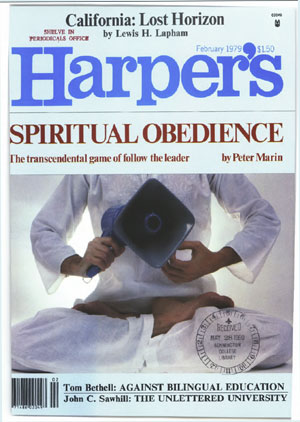

Spiritual Obedience: The transcendental game of follow the leader

by Peter Marin

Harper's

February 1979

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

A LETTER CAME the other day from a good friend of mine, a poet who has always been torn between radical politics and mysticism, and who genuinely aches for the presence of God. A few years ago, astonishing us all, he became a follower of the Guru Maharaj Ji -- the smiling, plump young man who heads the Divine Light Mission. Convinced that his guru was in fact God, or at least a manifestation of God, my friend gave his life to him, choosing to become one of his priests, and rapidly rising -- because of his brilliance and devotion -- to the top of the organization's hierarchy. But last week I received a phone call from my friend, who told me he intended to leave the organization, mainly because, as he said, he could neither "give up the idea of the individual" nor "altogether stop myself from thinking."

Then, a few days later, the letter came, scrawled unevenly on lined yellow paper, in a script more ragged than I remembered, and made somehow poignant by the uneven tone:

The decision in me to hang it up is the one bright light within me for the time being. Because what is actually the case is that I've lived very much the lifestyle of 1984. Or of Mao's China -- or of Hitler's Germany. Imagine for a moment a situation where every single moment of your day is programmed. You begin with exercise, then meditation, then a communal meal. Then the service (the work each member does). As the Director of the House in which I lived and the director of the clinic, it was my job daily to give the requisite pep talks or Satsangs to the staff. You work six days a week, nine to six -- then come home to dinner and then go to two hours of spiritual discourse, then meditate. There is no leisure. It is always a group consciousness. You discuss nothing that isn't directly related to "the knowledge." You are censured if you discuss any topics of the world. And, of course, there is always the constant focus on the spiritual leader.

Can you imagine not thinking, not writing, not reading, and no real discussion? Day after day, the rest of your life? That is the norm here.

What is the payoff? Love. You are allowed access to a real experience of transcendence. There is a great emotional tie to your fellow devotees and to your Guru -- your Guru, being the center stage of everything you do, becomes omnipresent. Everything is ascribed to him. He is positively supernatural after a while. Any normal form of causal thinking breaks down. The ordinary world with its laws and orders is proscribed. It is an "illusion." It is an absolutely foolproof system. Better than Mao, because it delivers a closer-knit cohesiveness than collective criticism and the red book.

Look at me. After a bad relationship, a disintegrated marriage, a long illness, a deep searching for an answer, I was ripe. I was always impulsive anyway. So, I bought in. That feeling of love, of community. The certainty that you are submitting to God incarnate. It creates a wonderfully deep and abiding euphoria which, for some, lasts indefinitely.

To trip away from such a euphoria, back to a world of doubt and criticism, of imperfection -- why would anyone reject fascism or communism -- in practice they are the same -- once one had experienced the benefits of these systems?

Because there is more to human beings than the desire for love or the wish for problems to go away. There is also the spirit -- the reasoning element in man and a sense of morality. My flight now is due out Dec. 5. I am hoping to last that long. I think that with a little luck, I will. If not, I'll call.

Love to you, K

Nothing is simple. A few days later my friend called again, his voice a bit stronger, still anxious to leave, asking me to make his travel arrangements. But this time he began talking about William Buckley, how he liked his work, how he had written to him, gotten a moving letter in return. I could hear, as he talked, the beginning of a new kind of attachment, the hints of a reaction tending toward conservatism, the touch -- ever so faint -- of a new enthusiasm, a new creed, something new to believe in, to join. Never having been to China, he had once extolled its virtues; now, without seeing it, he denounces its faults. His moods are like the wild swings of a quivering compass needle, with no true pole.

I remember going a few years ago to a lecture in which the speaker, in the name of enlightenment, had advocated total submission to a religious master. The audience, like most contemporary audiences, had been receptive to the idea, or more receptive, rather, than they would have been a while back. Half of them were intrigued by the idea, drawn to it. Total submission. Obedience to a "perfect master." One could hear, inwardly in them, the gathering of breath for a collective sigh of relief. At last, to be set free, to lay down one's burden, to be a child again -- not in renewed innocence, but in restored dependence, in admitted, undisguised dependence. To be told, again, what to do, and how to do it.... The yearning in the audience was so palpable, their need so thick and obvious, that it was impossible not to feel it, impossible not to empathize with it in some way. Why not, after all? Clearly there are truths and kinds of wisdom to which most persons will not come alone; clearly there are in the world authorities in matters of the spirit, seasoned travelers, guides. Somewhere there must be truths other than the disappointing ones we have; somewhere there must be access to a world larger than this one. And if, to get there, we must put aside all arrogance of will and the stubborn ego, why not? Why not admit what we do not know and cannot do and submit to someone who both knows and does, who will teach us if we merely put aside all judgment for the moment and obey with trust and goodwill?

The audience in question was a white and middle-class group, in spiritual need perhaps, but not only in spiritual need. They were also politically frustrated and exhausted, had been harried and bullied into positions of alienation and isolation, had been raised in a variety of systems that taught them simultaneously individual responsibility and high levels of submission to institutional authority. As a result, without adequate or satisfying participation in the polis, or the communal or social worlds, the desire for spiritual submission may reveal less of a spiritual yearning and more of a habitual appetite for submission in general. Submission becomes a value and an end in itself, and unless it exists side by side with an insistence upon political power and participation, it becomes a frightening and destructive thing.

There are many things to which a man or woman might submit: to his own work, to the needs of others, to the love of others, to passion, to experience, to the rhythms of nature -- the list is endless and includes almost anything men or women might do, for almost anything, done with depth, takes us beyond ourselves and into relation with other things, and that is always a submission, for it is always a joining, a kind of wedding to the world. There is, no doubt, a need for that, for without it we grow exhausted with ourselves, with our wisdom still unspoken, and our needs unmet.

But that general appetite is twisted and used tyrannically when we are asked to submit ourselves, unconditionally to other persons -- whether they wear the masks of the state or of the spirit. In both instances our primary relation is no longer to the world or to others; it is to "the master," and the world or others suffer from that choice, because our relation to them is broken, and with it our sense of possibility. In our attempt to restore to ourselves what is missing, we merely intensify the deprivation rather than diminish it.

Tibet in Boulder

DURING THE SUMMER of 1977, I taught for several weeks at Naropa Institute, a Buddhist school in Boulder, Colorado, begun by Chogyam Trungpa, Rinpoche,* who is considered by his American followers to be a sort of spiritual king. While there, I made most of the entries and notes that appear on the following pages. But they are selected from a longer manuscript, and I suppose they will not make much sense without an explanation of Naropa and what I was doing there.

Trungpa is certainly no fraud; prepared from childhood on to be the abbot of several monasteries in Tibet, he fled the country when the Communists took it over in 1959 and later came to America in 1970. He is believed by his followers to be the incarnation of Trungpa Tulku, an earlier Tibetan master, and to be heir to a tradition of "crazy wisdom" dating back 1,800 years to Milarepa and Padmasambhava, revered Tibetan saints. Trungpa's earliest American followers were drawn mainly from the counterculture, and I suspect that they are generally more intelligent, literate, and profligate than those drawn to other contemporary spiritual leaders. Forty years old, bright, witty, and a hard drinker, Trungpa also appealed to several artists and writers, many of whom -- like Allen Ginsberg -- became both his students and teachers at Naropa.

Trungpa's disciples are not nearly so well organized as members of some other modern spiritual groups. Though they sometimes live communally at the spiritual centers set up here, for the most part they live independently and separately and owe him allegiance or obedience only in terms of their spiritual lives. Nonetheless, Trungpa does wield power over some of them. His disciples apply to him for counsel as they might to Dear Abby, and Trungpa has even upon occasion strongly suggested to people whom they should marry. Many of his followers believe him to have magical powers gathered in Tibet. In general, however, the power that Trungpa has seems as much a result of what his disciples project upon him as of what they are taught.

I came to Naropa because I had been curious about it for a while, and because some people there, familiar with my writing, hoped that I would later write something about the school. When I first explained my misgivings about teaching there, the staff said to come anyway, and I went, having certain mild but not decisive prejudices, feeling a bit guilty about a summer spent so far from things I really cared about, but also curious and self-indulgent enough to want a few easy weeks in the mountains.

I taught two courses, both of which I had suggested: one on autobiography, which was filled to overflowing, and one on social action and morality, which drew only a handful of students. Not knowing quite how to fit me into their scheme of things, the administrators thrust me upon the poets in Naropa's "Kerouac School of Disembodied Poetics." Perplexed by my presence, a bit resentful of those who stuck me there, and as competitive and hermetic as poets can often be, they left me pretty much to myself. For the most part I went about my private business, knowing enough about summer schools in general to construct a separate life for myself, and finding my real pleasures in the mountains or among friends.

The dragon-horse of the I Ching. From The I Ching and Mankind, by Diana Hook (Rutledge,

Kegan, Paul, 1975)

Naropa, which is a year-round school, attracts most of its students during its two summer sessions. In general, the guest faculty is impressive: artists, intellectuals, and academicians who are flattered by the invitation to teach and genuinely hope to combine or enhance their own work with Buddhist ideas and meditative techniques. The 600 students who were there for each summer session ought not to be confused with Trungpa's regular disciples, who number perhaps 1,500 and are scattered across the country. The real disciples run, rather than attend, Naropa, and are associated primarily with Vajradhatu, an essentially religious organization coordinating the various activities and meditative centers set up by Trungpa during the past several years. Vajradhatu and Naropa are legally separate; though Trungpa often lectures at Naropa, his spiritual teaching is offered mainly in the activities of Vajradhatu, and Naropa is -- or so its administrators claim -- an attempt to leaven Western culture with Eastern wisdom. Whereas Vajradhatu is organized around a single truth and obedience to a single master, Trungpa, Naropa is more secular and various, with several points of view represented. Nonetheless, Tibetan Buddhism forms the heart of the summer's teaching. Most of the students there temporarily seem drawn by an interest in Buddhism, meditation, and enlightenment, and the most popular weekly events are the lectures conducted by spiritual teachers and the peripheral activities associated with them: studies in the Buddhist tradition, and instruction in meditation, without which, it is explained, one cannot understand Buddhist ideas.

The school has no campus of its own. Its central offices, along with a rehearsal hall, are on the second floor of a building on Boulder's mall close to the modish center of town, among the hip bars and health-food stores. Classes were held several blocks away in a large Catholic high school rented for the summer. Most of the summer faculty members were housed, along with some students, in a nearby apartment complex, which took on, as the summer progressed, the untidy and noisy, but not unpleasant, vitality of unmanaged tenement life. Trungpa's disciples were scattered around town in their own houses, and they spent most of their time in another building altogether, where Vajradhatu's affairs were conducted. There things appeared to be more orderly; the building -- efficiently busy, manned at the entrances resembled a bank or a mini-Pentagon. Trungpa himself was not at Naropa while I was there. He was off "on retreat" for the summer. His place had been taken by Osel Tendzin, the "Vajra Regent," who had more recently been Trungpa's prize student -- an American with an American name -- before being elevated to his new role. Trungpa had in no way abdicated his place at the center of the school and its disciples, but the trappings of royalty, and the attitudes of the disciples toward them, had passed entire from Trungpa to Osel. It is the position and not the man that commands obedience -- not so very different from the Catholic attitude toward the Pope. Osel was constantly attended in public -- as is Trungpa -- by a small legion of Vajra guards, rather muscular and doggedly loyal bodyguards who do his bidding. Their presence, as with many things at Naropa, was partly symbolic. But that does not mean it was purely ornamental. Symbols at Naropa take on immense weight and significance, often superseding everything else. I remember a friend telling me he had been asked by one of the guards to prepare a performance for Osel's birthday.

"What sort of performance?" he asked.

"We don't care," answered the guard. "Just make sure you do it as if it were for a king."

As for Boulder itself, it is a complex and curious place, as is all of Colorado. Nature is so overpoweringly present that one feels as if one has escaped the ordinary and arrived at a place more beautiful and innocent. But that is not the case. For a while, bored with Naropa, I wandered the town, picking up stories and myths. The state is a paranoid dream, with drugs flowing into towns from the south, and drug money from the southwest, and guns being run to Latin America, and ex-Green Berets and soldiers of fortune and agents from nine different federal security agencies, and the same odd mix of interests, influence, and alliances that turns up in Miami and Cuba or the drug trade in Southeast Asia. Rocky Flats is nearby -- where we reprocess fissionable material from all our nuclear weapons, and so is Cheyenne Mountain, our underground headquarters in case of war. The Rockies are honeycombed from one end to the other with installations of all sorts; a great war grows in the state over mineral and water rights; the state's powers include the Rockefeller and Coors families; branches of the Mafia contend with one another; many of the university professors are said to have extensive ties with the CIA; this is where several years ago a mysterious busload of Tibetans turned up stranded in a ditch, preparing for a counterinsurgent invasion of Tibet; where Thomas Riha worked at the University of Colorado on a secret project before disappearing without a trace in Eastern Europe; where his confidante, Gayla Tannenbaum, is said to have committed suicide from a dose of cyanide in the same hospital where they once hid Dita Beard; where the young man who murdered his uncle, the King of Saudi Arabia, went to school and was, some insist, recruited by CIA agents working in the Drug Enforcement Agency. It is here, too, that the wife of the Shah of Iran arrived with her full retinue on three private planes, to lecture at the Aspen Institute about social justice. In short, this is America, and the underside of town, invisible to tourists and Buddhist residents, is inhabited by bikers and hoodlums, outlaws and adventurers, rebels and Moonies, all percolating under the surface and at the edges of town and perhaps a better measure of our age than the stained glass and ferns of the singles' bars or the herb displays at the health-food stores.

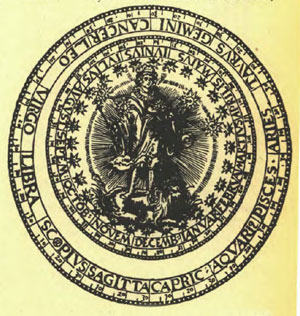

Dharmachakra: Veneration of Buddha turning the Wheel of the Law

Though I love these details and tales, I have no room for them here, and I mention them briefly as a way of setting the scene, for they are related to what goes on at Naropa. This, too, is the world -- the mix of power and violence and sophistication from which the students turn away, as if hoping to leave it behind even as it surrounds them and presses close.

And finally, one note of caution. What goes on at Naropa and Vajradhatu is by no means as excessive or oppressive as what some other sects inflict upon their members. I do not intend here an expose. In many ways, it is the sect's relative innocuousness that interests me. Even in Naropa's comparative normality one can see the tendencies that lead in more radical expressions to far more troubling ends. Finally, I should say that while passing through Boulder in 1978 I passed many of these pages on to someone at Naropa, explained that I intended to publish them, and asked if Trungpa would like to discuss them. The answer was no.

June 16

OF COURSE, one must not forget this is Vajrayana Buddhism, a particular tradition -- an aristocratic Tibetan line set free of moral constraint, in which all action is seen as play, and in which the traditional (if somewhat hazy) questions at work in Buddhism about moral responsibilities to sentient creatures are largely set aside. For the most part, moral and social questions disappear from all discourse, even from idle conversation, save when they are raised by outsiders. Then they are dealt with, a bit grudgingly, and always briefly.

The Naropa Institute embodies a feudal, priestly tradition transplanted to a capitalistic setting. The attraction it has for its adherents is oddly reminiscent of the attraction the aristocracy had for the rising middle class in the early days of capitalistic expansion. These middle-class children seem drawn irresistibly not only to the discipline involved but also to the trappings of hierarchy. Stepping out from their limousines, hours late for their talks, surrounded by satraps, the masters seem alternately like Arab chieftains or caliphs. Allegiance to the discipline means allegiance to the lineage, to the present Vajra, as clearly as if it were allegiance to a king.

If there is a compassion at work here, as some insist, it is so distant, so diminished, so divorced from concrete changes in social structure, that it makes no difference at all. Periodically someone will talk about how meditation will lead inevitably to compassion or generosity. But that, even according to other Buddhists, is nonsense. Certainly here it is nonsense. Behind the public face lies the intrigue and attitude of a medieval court, and that shows up in the peculiar and "playful" way in which Buddhists enter the world of hip capitalism. It is no accident that they are in Boulder, where such businesses flourish. America is what it is, and business is play, and so the Buddhists happily take part in the moneymaking, unconstrained by any notion of a common good, and certainly unconcerned about the relation of individual conscience and the dominant attitudes toward the entrepreneurial self and the primacy of property.

For Vajrayana Buddhists, the "open space" of the world is an arena for play rather than for justice. Nothing could be further from their sensibility than the notion of a free community of equals or a just society or the common good. In their eyes justice is another delusion, another proof of personal confusion. For this reason one begins to see how well the institute fits into Boulder, and why it has such an attraction for certain intellectuals and therapists.

June, 17

FOR THE SAGES HERE, every form of pain can be understood in terms of attachment or ego. Conscience does not exist, nor what Blake would have called a yearning for Jerusalem. Precisely those joyous powers and passions that feel, in the self, like the presence of life and its graces are taken to be fictions, and discounted or abused. In that, ironically, Naropa becomes, as its founders want, a living part of American intellectual life. In its denial of the felt world of persons and the lessons to be learned there, the truths to be found in others, it shares the limitations of intellectual America, and it caters to its weakness.

This particular brand of Buddhism is neither quite so morally aware as some Buddhist traditions nor so humble as others. Because it is elitist, aristocratic, and in some ways feudal, there lies at its heart, or at least close to the heart of Trungpa's aristocratic thought, a disdain for politics and for the yearnings behind it.

Though Trungpa's spiritual views lead inevitably and sometimes quite prettily to theories of radical aesthetics (see, for example, how another brand of Buddhism leavens the work of John Cage), and though one can even base upon them a fairly radical psychology, somehow they emerge, in his talks, as reactionary, establishmentarian politics -- something Trungpa has in common with most spiritual leaders who appeal to America's mindless middle class. The zeal one feels at work at the institute is in some ways simply a zeal to establish itself at the heart of American mainstream life, to conventionalize itself and make itself respectable. In that regard, Trungpa's early connections with the hippie or fringe community appear to be simply the easiest or only available way to build a foundation for his ensemble.

June 18

WHEN TRUNGPA DOES TOUCH upon politics, as he sometimes will in his lectures, it is always to devalue it, to set it aside. And when one raises with his disciples various questions about moral reciprocity, human responsibility, moral value, or political action, they dismiss such inquiries, muttering about "all sentient creatures" or confused attachment to the world. But one must not make the mistake of thinking that they are otherworldly. Far from it. Trungpa and his students are very much of the world, and enter it in terms of business enterprises, the expansion of their institute, and so on. Trungpa seems to have no trouble with the structure of American capitalism, the idea of property, the underlying relations between castes and classes of persons. These, I believe, appear to him divinely ordered -- a kind of spiritual hierarchy hardened into human norms. The notion that individual well-being hinges on change does not occur to him any more than it seems to have occurred to his predecessors in feudal Tibet.

The fact that this notion is taught by a privileged class of priests to their followers ought to make it somewhat suspect, of course. But one can also understand its appeal to middle-class Americans, whose nervousness is such that they would like to believe that spiritual progress is possible without further upheavals in history and the loss of their privileged estate.

Trungpa's implicit conservatism seems, then, both appealing to his followers and also destructive to qualities in them still feebly struggling to stay alive. And that is to say nothing of its real consequences in the concrete world -- those that will show up not in the fates or destinies of these middle-class Americans, but in those of the poor and black and disenfranchised, those who invariably find themselves suffering the results of reactionary American politics. For those whose well-being rests upon either the structural transformation of society or changes in dominant American notions about justice, moral philosophies like Trungpa's, and the encapsulated moral world in which they are taught, can only spell further pain, if they are widely taken seriously, or remain unleavened by moral ideas rooted in a vision other than that offered at Naropa.

I do not suggest that Trungpa actually means that kind of harm to anyone, or is an incipient fascist. Certainly the obvious eclecticism at work in the summer institute, and the plethora of views expressed, and the relative freedom of their expression, leave intact at least a minimal sense of the free play of thought and a willingness to subject Buddhist views to all sorts of challenge and criticism. But to claim for it -- as is often done -- a supremacy of vision, or to demand, in its name, a singular allegiance, or to denounce in its name all other devotions, attachments, or obligations as confusion (as is also done) is a violence done to those present. It becomes, in that instance, not the healing that it might be, but a still further cause of pain.

June 19

YESTERDAY WE SOUGHT among the places on our map a town still untouched by the modernity that has overwhelmed these mountains. Everywhere now there rise from the steep valleys row upon row of condominiums and chalets, and the signs of the culture that accompanies them: hip stores, self-conscious fashion, the fancies of a white American hipness now coming into its own. In many of the towns, to find something authentic one must go to the outermost avenues, to the traditional gas stations and cafes that, though scars on the landscape, have at least a reality the make-believe cuteness of the towns -- Dillon, Vail, Georgetown, Frisco, Boulder, and Aspen -- do not have.

In these towns, one feels at the precious, airless dead end of culture, among fashionable sleepwalkers. Each seems to mimic and mock what its builders remember of their college campuses. Complete with apartments, pools, tennis courts, groceries, jewelry stores, restaurants, and bars made to look like saloons, these towns close in on the soul at the same time that they sustain its life. They remind one of the "sundomes" Ray Bradbury once described in a story about rainswept Venus: self-enclosed pockets of weather creating a world totally separate from the planet's life.

A few nights ago, watching the faces of the rapt students as they listened to a Buddhist speaker, it appeared to me that the world into which they seemed compelled to move was the spiritual version of these modish towns. Though they sought surcease from the tribulations of the self, they seemed trapped in themselves by precisely the absence of what the teacher denounced: a passion for the world. Peculiarly, they seemed engaged in trying to escape an appetite that no longer seemed alive in them. Though the administrators of the institute were calm and had a kind of clarity, the atmosphere around them seemed humanly empty, too hygienic, too claustrophobic by far. Lacking both irony and joy, the atmosphere was watery, insubstantial. Watching it, moving through it, one felt very little. There was not enough passion present in it to engender any kind of reaction. The world itself seemed so absent, so distant, that the dislocation between this reality and that other seemed itself to have become unreal.

An illustration from a Jataka, showing the Buddha's past life as a crane.

June 20

SOMETIMES THE ENTIRE institute seems like an immense joke played by Trungpa on the world, the attempt of a grown child to reconstruct for himself a simple world. It is no accident that he should construct it here, in Boulder, through the agency of yearning Americans whose ache for a larger world is easily reduced to a passion for aristocratic form. He makes easy use of the voracious elitism by which American members of the middle class increasingly justify their wealth or rationalize their sense of separation from the world. But what makes it painful to see is that there exists in many of these young students a pain and shame and unused power that issues from the deepest and best parts of themselves and that they must learn to live and speak of. But there is no way for them to do that through Buddhism, no teacher to help them, no rhetoric to reveal to them what they feel. Instead, their human yearning, the ache of conscience, the inner feel of justice, the felt sense of freedom are passed off as illusions, as Western childishness. These impulses, ironically, are destroyed in the name of a spiritual wisdom perhaps necessary to complete them. But that destruction is not in any way inherent in wisdom or even in the tradition of meditation. It is inherent in the priestly class. Aristocrats of any sort, after all, especially those given to pomp and hierarchy, are not the best sages to consult about political frustration or moral pain.

As is true of people in almost any contemporary institution, these students are better than what they are taught. Just as, in the Sixties, the truths of their rebellion, garbled as it was, exceeded the institutional truths of their teachers, so, too, the yearning of these students unused is abused by the institution that defines reality and truth for them. Troubled not only by their separation from a felt connection to the world, these students also experience the pain of a vision of self or human nature that allows no room for what they feel about the world, and offers no way to express it. Their pain is not spiritual; it is moral. Their problem is to regain their moral lives in the way that we have recently struggled to regain our sexual lives. But just as we looked mistakenly to sexuality for certain political or moral satisfactions, thereby corrupting that realm, now we mistakenly search in the spirit's world for the same satisfactions; just as Columbus, sailing among the American isles, thought himself to be in the Indies and called everything by the wrong name, so, too, we drift in a landscape that we do not understand, and we have the wrong names for things.

June 21

WE HAVE COME TO DENVER, to Lakeside, an amusement park built in the Twenties, to picnic on the lawn under the cottonwood trees. Just yesterday we were in the mountains, crossing a series of passes at 12,000 feet, above the timberline, where the tundra was covered everywhere with small blue and white flowers. The wind played about us as we wound our way among melting snowbanks to come finally to what seemed like the top of the world. In the distance we could see nothing human, merely the high saddles of mountains, their tree-covered flanks, and the tall cloudy skies above them barely distinguishable from the snow-white peaks. There was a beauty to that almost beyond belief, but there is something no less beautiful in all of this: the amusement park with its small lake and weathered, brightly painted buildings, the fat lady laughing above the ride through the fun house, lovers and children passing on the narrow paths or gathered at tables under the trees. This, too, is a gift, perhaps more profound than that other, because its beauty is crowned by human presence. Sometimes, somehow, almost as if by accident, we get things right; the spaces we create for one another --- like this small amusement park -- reveal the presence of the human heart. The indifferent generosity of nature gives way to the human generosity of the accidentally just city.

Now at noon, we sit on the grass beneath this tall tree, having within reach the fruits of countless harvests: wine, bread, cheeses, fruit, chocolate. I look at the grass, the sky, the passers-by, my companions, and my heart fills with a joy equal to any more obviously mystical or religious sentiment I have ever had. There is nothing beyond the absolute beauty of the transience of this day -- this wind, this ease, this flesh. It arises from the heart in answer to a human presence, and one understands -- if only for a moment -- what it would mean to be free.

There are those, back at Naropa, who would escape all this. A few nights ago, in answer to some questions about the nature of joy, one of the sages in residence, a Buddhist monk, answered that joy was always followed or equaled by suffering, and that enlightenment meant leaving them both behind. Nobody in the audience bothered to argue. Yet there is, I think, a discipline graver and more demanding than the one offered the audience. It is open to those whose joy in life seems to justify whatever suffering is entailed. It is a passion beyond all possessiveness, a fierce love of the world and a fierce joy in the transience of things made beautiful by their impermanence. I would not trade this day for heaven, no matter what name we call it by. Or rather, I think that if there is a heaven, it is something like this, a pleasure taken in life, this gift of one's comrades at ease momentarily under the trees, and the taste of satisfaction, and the promise of grace, alive in one's hands and mouth.

From In Praise of Krishna, by Edward Dimock and Denise Levertov (Doubleday, 1967)

Vara mudra

The discipline of living with this grace, of seeking it out, is what calls to some of us as surely as the escape from pain calls to others. This is not the cessation of passion, but its completion, its humanization. The question posed by this discipline is a simple one, demanding a lifetime as answer. It is: Can one live as man? It is a call that echoes in the soul as a significance of being: a sense of meaning as a power that runs beneath all thought and lifts the flesh beyond all questioning, as a certainty of belonging in a world that seems, on its face, indifferent to our presence. Here, in the city, where we have made our homes there lives a beauty that exceeds -- when it is present -- the beauty of the mountains, because it is human, and thereby lifts the heart even higher. It is not antithetical to the mountains, it calls to the same thing in the soul; it, too, is what one might call, with Giono, "the song of the world." Stone, sky, earth, and tree -- these beckon to man as enigmas, facts, and gifts: a world beyond that suddenly opens in the soul to reveal itself, outside of us, as a home. That same thing is true of these others, this human community. This, too, opens in the soul, revealing itself as our home. This beauty, not accidental, issues from the human hand, is a song of his joy. It is like the beauty of certain cities, of certain human landscapes, in which human habitation merges with sky and sea to form a world that would vanish if either were missing.

June 23

TODAY, WHEN A STUDENT asked me what I thought of all this, I filtered through my mind all the polite or witty things I might say, and then responded with what I really meant: "I think it is beneath contempt." And that is true. Beyond the reasonableness of my controlled responses, all of this seems worse than absurd, mainly because at the heart of its senselessness lies a smug self-congratulation beyond all belief. Things here are closed, small, careful, secure. I remember, as a child, hating my obligatory visits to the synagogue, hating them with the passion of a secularized Jew, as if still stirring in my blood were the currents of the impulses that took a whole people out of their tiny towns and shtetls, and into the larger world -- as if gasping for air. If there is a god, it is a god of the open world, oceans and deserts, of great distances and beasts. How he must shudder at these shuttered truths, these betrayals of the world.

June 24

TWO SUMMERS AGO a well-known poet, P [William Stanley Merwin], came to Naropa to teach for the summer, accompanied by a lovely Oriental woman, W [Dana Naone]. * Trungpa befriended and apparently impressed them both. At the end of the summer, P, who had already had experience with Catholic modes of meditation, asked Trungpa if he and his friend could attend the fall retreat ordinarily open only to regular disciples. Admission to these retreats is always much sought after, in part because it is a sign of Trungpa's approval, but also because it is here that certain truths are supposedly revealed for which the other aspects of the discipline are simply a preparation. For several weeks Trungpa becomes the "Vajra Master," an absolute authority in all things, a spiritual master who is himself almost divine. The retreat involves alternating periods of meditation and formal teaching, but these are not nearly so serious as one might imagine; they are also marked by much celebration, drinking, and horseplay, and rumors abound about their sexual aspects -- lovemaking, wife swapping, et cetera.

The particular retreat in question, held at a rented ski lodge in Snowmass, Colorado, and involving about 125 people, apparently was no exception.

During the first several weeks there were the usual incidents of roughhousing and hazing, most of which make it sound more like an extended fraternity weekend than a religious event. There was a slow escalation of what began as playful violence; Trungpa took to using a peashooter on unwary students; there was a strenuous snowball fight between Trungpa's Vajra guards and his other disciples; at one point the disciples trapped Trungpa in his car and rocked it violently in the snow; there were playful student plans (in which some claim P participated) for releasing laughing gas at one of Trungpa's lectures; and once, apparently, some of the students trashed Trungpa's chalet.

During all of this P and W kept to themselves, just as they had done at Naropa during the summer. They spent their free time together in their room, coming down only for lectures, rituals, or meditation. Their aloofness, which the community members had resented all summer, took on, in the new context, a more disturbing quality. Many of the disciples later described it as antisocial, or an insult to Trungpa, or a form of rebellion or egotism, or precisely the kind of personal detachment and self-protectiveness that Buddhism is meant to dissolve. This communal resentment, in the claustrophobic atmosphere of the retreat, escalated in much the same way as did the initially playful roughhousing; both of these attitudes found their expression on Halloween night.

From The Cult of Tara, by Stephan Beyer (University of California Press, 1973)

A party takes place -- though nobody is quite clear whether Trungpa has arranged it. These parties have reputedly been more or less bacchanalian. Everyone is expected to come in costume; some disciples spend days planning and making their outfits. That night, at the party, Trungpa is slightly drunk and perhaps feeling bad-tempered. One of the participants later described the way Trungpa greeted her that evening: "He was being so brutal, and like clawing my arm, and just biting my lip, so vicious." But she was, after all, dressed as a biker, and perhaps Trungpa's approach was satiric and mocking, as is sometimes his way.

"I had a whole interchange with Rinpoche. I can't remember the order. I think it must have happened before ... He called me up to him. He saw me, and ... we got into this whole thing. He was picking up on my costume. The whole aggression. (She was in costume as a biker.) We started sort of like making out. I mean it was very lavish, and all these people were dancing, and sitting around (laughs), and we just started doing this whole thing. And he was being so brutal. He was being so physically brutal, and like, clawing my arm, and just, biting my lip, just so vicious. And then he did this whole thing with my cheek (bit into the skin, leaving tooth marks), and I was in this state of mind -- well, if that's what he wants, that's what I'll give him too. And I just came back with it. And we're in this intense, you know (makes unh-ing sound) like this you know, very tense, very, very tense ... Somebody else came up or something and I managed to get away. But it was very nonverbal, direct, powerful, intense brutal communication. I didn't know what to make of it at all."

-- Interview with Barbara Meier (Faigao) 6/29/77

-- Behind the Veil of Boulder Buddhism: Ed Sanders, The Party, by Boulder Monthly

And earlier in the evening, a woman is stripped naked, apparently at Trungpa's joking command, and hoisted into the air by the Vajra guards, and passed around -- presumably in fun, though the woman does not think so.

Persis McMillen was one of those first stripped at the Halloween party. Early in the evening Persis met Trungpa and he told her that he was going to take off people's clothes. She thought he was kidding, didn't take it very seriously. After talking to her, Trungpa disappeared for an extended period of time....

Regarding the actual stripping, Persis McMillen recalled, "It happened so fast." She remembers the guards surrounding her, and it took them two minutes to take off her clothes. She was shocked: she didn't resist. The guards hoisted her while nude, aloft. Being a dancer, at first she took a poised dance pose, but after a few seconds felt differently: felt, in her words, "really trashed out." She ran upstairs. In her own words, she "felt sick," and "literally stripped," and " ... very, very upsetting."

-- Interview with Persis McMillen (Santoli) 7/1/77

-- Behind the Veil of Boulder Buddhism: Ed Sanders, The Party, by Boulder Monthly

The syllable om.