Re: Dragon Thunder: My Life with Chogyam Trungpa by Diana Mu

Part 1 of 2

FIVE

January 4, 1970, the day after our wedding: When my mother recovered somewhat from the shock of hearing the news of our marriage, she moved quickly. She called relatives and friends to ask them to help her get the marriage annulled. She also phoned us the next morning, in a fairly hysterical state. I wrote in my diary, "Mummy said she would turn the press against Ami (my special name for Rinpoche), and we'd be arrested in England." This did not prove to be true, but it was a worrisome threat.

My aunt and uncle also phoned that morning, and they arranged to meet us for lunch that day. My mother had asked my Aunt Veronica and Uncle Michael to drive up to Edinburgh from their home in Northumberland, which was only an hour or two away. She wanted them to find out more about what was happening and to see if they could persuade me to give up the marriage. They drove up to our hotel in their big brown Bentley, and Rinpoche and I got in the back seat. My aunt and uncle were in the front, and they proceeded to have an awful fight about how to get to the hotel where we were going to have drinks. In the middle of this, my aunt turned to me and said, "You know, marriage isn't easy under the best of circumstances. I don't know how you can expect this to work out."

My uncle ordered drinks for us at the bar. Rinpoche had whiskey, and given the circumstances, he drank a fair amount. My uncle tried to open a conversation with him, saying, "Well, now, do tell me about yourself. When did you become a priest?" Rinpoche answered, "Oh, I was a year old." Of course, this was incomprehensible to my uncle, and he began to sputter. He didn't know where to begin to get a handle on the whole situation. The conversation degenerated from there, and he and Rinpoche proceeded to get drunk. My uncle started yelling at him, calling him a cradle robber and a baby snatcher.

Then, seemingly out of the blue, my uncle looked across the street and said in his most arch English accent, "Well, there's a Chinese restaurant. That looks appropriate! Let's eat there." We all got up and walked across the street, which was not that easy for Rinpoche, who was still using a walker after his accident. My uncle seemed to have no idea that going to a Chinese restaurant would not necessarily be the most pleasant experience for a Tibetan. However, Rinpoche loved Chinese food and had no particular animosity toward the Chinese people as a whole. Nevertheless, my uncle's lack of sensitivity struck me as a reflection of his narrow-mindedness. To my uncle, one Oriental was the same as another regardless of whether they were Chinese, Japanese, Burmese, or Tibetan.

After we sat down at the restaurant, my uncle started yelling at the waiter, "Boy, boy, come over here." When the waiter came along, my uncle said, "Bring something Chinese!" The waiter said, "I'm very happy to bring you a menu, sir;' to which my uncle replied, "Just bring something Chinese. Anything Chinese. It's all the same anyway." Not surprisingly, nothing was resolved at dinner. Toward the end of the meal, my uncle said to Rinpoche, "Well, you'd better go to America. You'll do well in America, because anything goes there."

After this painful evening with my aunt and uncle, Rinpoche and I felt quite alienated from my family, and we thought about driving to Samye Ling the next day. \We had already decided that we would not be going back to the ugly scene at Garwald House.) However, the next morning, Tessa and her boyfriend Roderick arrived at our hotel. They had traveled to Samye Ling the day after the wedding, where they had spent the night. They told us that people there were having a terribly difficult time accepting the marriage and that we shouldn't return right away. We decided to take a short honeymoon to Findhorn, a spiritual community in northern Scotland. We invited Roderick and my sister to drive up with us. That day we drove all the way to Inverness, which was a beautiful drive through the landscape of northern Scotland, much of which reminded Rinpoche of Tibet. I remember sitting in the car as we went through the highlands, staring at Rinpoche, thinking, "I can't believe I'm married to you. This is amazing. I can't believe this has happened." I felt like the luckiest person in the world, even though the situation definitely had taken some bizarre twists and turns.

The Findhorn community is famous for growing huge vegetables in the rocky highland soil and for talking to the fairies. It was started by Peter Caddy and his wife Eileen, who greeted us when we arrived. Rinpoche and I were given a nicely appointed trailer, and Tessa and her boyfriend also stayed on the property. It was a brief but delightful honeymoon. We took walks around the property, and Peter Caddy showed us artwork done by people there, which had something to do with extraterrestrials.

While we were there, I consulted the I Ching, and I got "The Marrying Maiden," with the first line a changing line, which mentions "the lame man who is able to tread." I found this amusing, thinking of it literally as referring to Rinpoche and his difficulties walking. The line said that undertakings would bring good fortune.

During our time at Findhorn, I was introduced to Rinpoche's custom of waking up in the middle of the night wanting something to eat. He had this habit for years, for most of his life in the West, in fact. While we were at Findhorn, I got up every night and made him a sandwich.

We also visited an ancient Benedictine monastery nearby, Pluscarden Priory. After Rinpoche mentioned that he was a Tibetan lama, the monks were very interested in him, and they gave us a complete tour of the facilities. We attended services there and had an interview with the prior. Rinpoche particularly enjoyed the Gregorian chanting used in the service, as well as the sweet-smelling incense, and he purchased some to take back to Samye Ling. He felt the monks were following a valid contemplative tradition there and that they were practicing the heart of Christianity. He was quite impressed by their contemplative lifestyle and was inspired to see people practicing an authentic Christian monastic tradition.

At the priory, Rinpoche talked to the monks about his relationship with Thomas Merton, whom he had met in India in 1968, a short time before Father Merton's sudden death. They had drinks together in a bar in Calcutta and were quite taken with one another. Merton commented in the journal he kept at the time, "Chogyam Trungpa is a completely marvelous person. Young, natural, without front or artifice, deep, awake, wise. I am sure we will be seeing a lot more of each other." Rinpoche, looking back years later on their meeting, said of it, "I had the feeling that I was meeting an old friend, a genuine friend. In fact, we planned to work on a book containing selections from the sacred writings of Christianity and Buddhism. . .. He was the first genuine person I met from the West."1

After our visit to Pluscarden, Rinpoche and I discussed the Christian contemplative tradition. I think it was the first time we ever talked about the relationship between Christianity and Buddhism. We joked that our children could become Christians as their rebellion against their parents. I asked Rinpoche, "What would you do if one of our sons said he wanted to become a Christian priest?" And he said, "I would encourage him to become the best Christian priest that ever existed; he would have to do, it completely, fully." He certainly didn't feel that he had cornered the market on wisdom. He appreciated the wisdom and discipline in other traditions. I didn't have a very good impression of the Christian faith, based on my own repressive experiences, but he helped me to see that there was more to it than the conventional approach.

Our time at Findhorn came to an end all too quickly; and we reluctantly resolved to go to Samye Ling, not knowing what to expect. When we arrived there, we were pleasantly surprised to find that a very nice bedroom had been prepared for us. An elaborate thangka of the Buddha had been hung in our room, filling an entire wall. It was a gift to Rinpoche from the queen of Bhutan, Ashi Kesang, when he visited there in 1968. Having this magnificent painting in our bedroom gave me a feeling of acceptance. One of the young monks living at Samye Ling, Samten, presented us with the traditional Tibetan offering of white scarves, or khatas, and talked about the positive significance of our marriage. Superficially at least, there was a sense of being welcomed.

Although we tried to settle in at Samye Ling, almost immediately we began making plans for our departure. Rinpoche gave some thought to returning to live in Asia since things had become so difficult in Scotland. He had me write to a university in Hong Kong, asking if they had a teaching position for him. They wrote back and said that if he could teach Tibetan, they would like him to join the faculty. I convinced him, however, that this was not the direction we should go. He also had been talking about making a visit to America, to do a lecture tour and to receive additional medical care there. Several close students who had left Samye Ling were in the United States looking for land for a meditation center on the East Coast. I encouraged him to think about going to America as soon as possible.

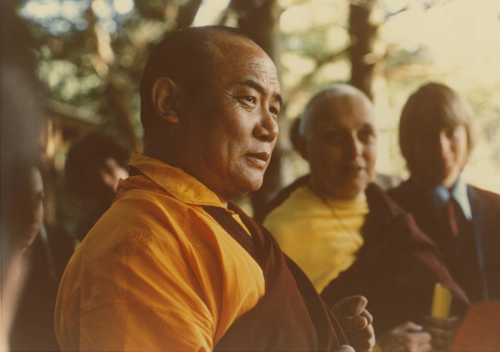

We stayed at Samye Ling for about two-and-a-half months. While we were there, I took Tibetan lessons with one of the monks, Phende Rinpoche, and studied thangka painting with Sherab Palden Beru. He was always very warm toward me, and he adored Rinpoche. He had some initial difficulty with the idea of our marriage, but after he adjusted, he was very kind to both of us. Rinpoche spent most of his time in our room, although occasionally he would come down to the shrine room during the pujas, or religious services. During this period, he sometimes wore monks' robes, tied with a yellow sash to indicate that he was a married lama. I learned to help him dress. Because of the accident, he needed my help. Other times, he wore Western-style dress, men's trousers with a blue button-down shirt and a maroon cashmere sweater. In that era, even his Western clothing often had a little bit of monastic feeling. He loved to wear a turtleneck that was the color of a monk's saffron robe.

During this period, Rinpoche still had to wear a caliper, or a brace, for his left foot and lower leg, which I used to help him put on. When we were first married, he used a walker, but he soon graduated to a walking stick, and eventually he was able to walk just with the caliper. In the long run, he didn't even need that, although he always had orthopedic shoes specially made for him.

Akong would not allow Rinpoche to lecture at Samye Ling. It seemed to be a, control issue. Rinpoche, however, did travel to other parts of Britain to teach. Once he was invited to speak at Bristol University. We stayed the night with an Indian family who was hosting the talk. Another time, we went down to Cambridge for Rinpoche to give a talk. We visited Ato Rinpoche and Alithea while we were there. Since meeting in India, Trungpa Rinpoche and Ato Rinpoche had remained close colleagues and friends. Perhaps because Ato Rinpoche had experienced obstacles to his marrying an Englishwoman, he and his wife were very understanding of our situation.

Since Rinpoche could not give talks· or group teachings at Samye Ling, most of his personal contact with students was in the form of private interviews, which were held in our room. He often set aside several hours a day for interviews. During that time, I practiced meditation, worked on my thangka painting, or handled Rinpoche's correspondence for him. We were preparing for the celebration of Losar, the Tibetan New Year, which would occur that year in early February, and I helped address New Year's cards for Rinpoche. Akong even gave me a typewriter and a place to work. A postcard came from a Mr. Karl Usow in Boulder, Colorado, inviting Rinpoche to visit there and teach at the University of Colorado. We both liked the mountains shown on the front of the card, and Rinpoche said it reminded him of the mountains in Tibet. I wrote back to Karl on Rinpoche's behalf, saying that we would try to come to Colorado for a visit.

One morning at Samye Ling, Rinpoche's interviews went on much longer than expected. Finally, I returned to our room to see what was up. I walked in on him passionately embracing a young woman. I was devastated. I locked myself in our bathroom and sat on the floor crying for hours. I didn't know what to do. I wondered if! should leave Rinpoche. He kept knocking on the bathroom door, but I repeatedly told him to go away.

After several hours, I came out, and we talked. Rinpoche was very sweet. He didn't seem to be avoiding or concealing anything, neither did he seem embarrassed. In some respects, it was an absolutely intimate and direct moment. He said that our connection was very deep and important to him. He told me openly that he expected that he was going to have intimate relationships with some of his female students, but that it didn't mean there was a problem with our relationship. Rinpoche said that in fact it was only because he had such trust in our relationship that he felt it would be possible for him to have these other relationships.

This is a very personal example, from my own life, of Rinpoche's truthfulness. He never lied to me about what he was doing. He was quite willing to talk about what had happened. The communication was so direct and real that I felt I could relax, and I started to let go of my conventional reference points. Rinpoche and I were deeply in love, and I didn't feel that he was using another relationship to blackmail me emotionally in some way.

On a fundamental level, Rinpoche was the most loyal husband I can imagine. In fact, our relationship went much deeper than many conventional marriages. My heart connection with him went far beyond the issue of sexuality, and I knew this from these very early times. As time went on, I felt that many relative difficulties were not fundamental problems -- if I let myself feel that deeper connection.

Although I had the formality of marriage with Rinpoche, my union with him was unique. We called it marriage, whatever it was, but Rinpoche was much too big a personality to trap into a monogamous relationship. It just couldn't be. Rinpoche was not an ordinary husband. He was not an ordinary man. I couldn't be possessive of him. I know that this may be difficult for people to accept, but it is my experience.

His life was dedicated to working with other people and their state of mind. In answering a letter from a student in 1971, he wrote: "I work with people -- that seems to be my reason for existence."2 I came to feel that if that sometimes carried over into sexual intimacy, that was okay. I never felt these relationships were an exploitation of his students. It was a way for him to create further intimacy with people. From a broad perspective, I came to realize that Rinpoche definitely was not here on this earth solely to be my sexual partner. It was not always easy or pleasant for me to accept this, but it was really okay.

In Rinpoche's monastery, the monks did a chant invoking the incarnations of the Trungpas, of which Rinpoche was the eleventh. Rinpoche's students in the West now do this chant as well. There is one stanza for each new Trungpa. In the stanza for the Eleventh Trungpa -- my husband -- he is compared to the Mad Yogi of Bhutan, a revered teacher who lived in the nineteenth century. He was famous both for the depth of his wisdom and for being very wild-drunken and bawdy. This was a very unusual reference because the other Trungpas were generally saintly monks, quite reserved in their behavior. This lineage supplication was written when Rinpoche was about ten years old, so it must somehow have been obvious to the revered lama who wrote this text that this Trungpa would be an unconventional person, another mad yogi.

In fact, Rinpoche's sexual experiences began before he left Tibet. A little while after we were married, I had a dream that he had a daughter in Tibet. I woke up and I said, "I had this ridiculous dream." "Oh," he said when I told him the dream, "It might be true." Then he told me about a night he spent with a Tibetan princess. He was in a procession with a beautiful princess from an outlying area, and he became infatuated with her. He managed to get close to her and suggested that she climb in through his window that night. She did, and they slept together. Before leaving Tibet, Rinpoche saw her again at some public event and she was clearly pregnant. So he might have had a daughter somewhere in Tibet.

As much as I appreciated my husband, I wasn't always accepting of his behavior. When we were first married, Rinpoche told me that it was normal for Tibetan men to beat their wives. I told him this was barbaric, but he said that it was just common practice. In the first few months of our marriage, he tried -- not very convincingly -- to slap me a couple of times when we were arguing. I said to him, "What do you think you're doing?" And he said to me, "This is just what Tibetans do." I felt that this was definitely not okay. I waited until he was asleep one day, and I took his walking stick and began hitting him as hard as I could. He woke up, and he was quite shocked, and he said, "What are you doing?" I said, "This is just what Western women do." He got the message, and it was never an issue again.

If you think about it, Rinpoche had no idea how to be a husband. He went to live in a monastery when he was thirteen months old, and although his mother came and stayed nearby until he was five, he had virtually no experience of family life. His role models were his gurus, and he had great examples in that area. He grew up as a monk, a student, and a Buddhist teacher, but he had to learn what it meant to be a householder, a husband, and a father.

In fact, at the time that we married, Rinpoche's seven-year-old son, Osel Mukpo, was living at Samye Ling. When Rinpoche visited India and Bhutan in 1968, he told Konchokla, Osel's mother, that he wanted to bring their son back to Scotland to live with him. It took a while to arrange this, but eventually he was able to come over. The first time I saw Osel at Samye Ling, I was struck by his physical beauty and small stature, the latter probably a result of malnutrition in India. He was very shy and spoke only Tibetan at the time. I remember him going off to his first day in kindergarten in a jeep with a local Scottish fellow, Mr. McTaggert. This beautiful, small, and very shy child was sobbing as the car left.

Osel arrived in England around the time of Rinpoche's accident. They had a very affectionate relationship, although Osel was shy around his father, understandably so. Rinpoche had asked the monks to look after his son while he was recuperating at Garwald House, since he was in no position to personally care for his son. When we arrived at Samye Ling after the wedding, Osel was living in the monks' quarters. In addition to attending the local school, he was being tutored in literary Tibetan by Akong and the other monks. They were apparently very rough with him. It seemed to be some sort of archaic method of Tibetan education.

Soon after I married Rinpoche, Osel had a high fever, and the monks put him to bed with no pajama top on. I felt that this was not the proper thing to do, so I asked one of the monks to put a top on him. The monk replied, "Oh no, it's good ifhe's cold. He'll get rid of the fever quickly." At that point, I said, "This is enough," and I got an extra mattress and moved him into our bedroom with us. He stayed in our room with us until we left for America.

In general, Rinpoche and I were very isolated from others during this period. Few of Rinpoche's close students remained at Samye Ling. Josie Wechsler, the English nun, was devoted to Rinpoche, and a few other close students were still around. A few friends would occasionally visit or invite us over, such as Ato Rinpoche and Alithea. Stash and Amalie lived nearby; and we would get together with them sometimes. Maggie Russell, whom Rinpoche had wanted to marry, came to visit once. I thought it was great that she had her own car. We spent a great deal of time alone, however, and there was a terrible underlying atmosphere of aggression toward us at Samye Ling.

During this time, Rinpoche's relationship with Akong continued to degenerate. In addition to their disagreement over the presentation of Buddhism in the West, there were other points of contention. Rinpoche was quite disappointed with how Akong related to the mental illness of one of the young monks at Samye Ling. He had to be hospitalized because of a nervous breakdown. Rinpoche felt that, rather than working with this person, Akong's main concern seemed to be to hide the situation from everyone. Rinpoche and I went to visit this monk in the mental hospital.

Akong was terribly mean to me. He put me on the work schedule to do dinner dishes almost every night. If he didn't like the way I did the dishes, he would knock on the bedroom door and tell me to come down and do them again. It felt like a humiliation tactic. This, of course, added to the tension that was building between Rinpoche and Akong.

FIVE

January 4, 1970, the day after our wedding: When my mother recovered somewhat from the shock of hearing the news of our marriage, she moved quickly. She called relatives and friends to ask them to help her get the marriage annulled. She also phoned us the next morning, in a fairly hysterical state. I wrote in my diary, "Mummy said she would turn the press against Ami (my special name for Rinpoche), and we'd be arrested in England." This did not prove to be true, but it was a worrisome threat.

My aunt and uncle also phoned that morning, and they arranged to meet us for lunch that day. My mother had asked my Aunt Veronica and Uncle Michael to drive up to Edinburgh from their home in Northumberland, which was only an hour or two away. She wanted them to find out more about what was happening and to see if they could persuade me to give up the marriage. They drove up to our hotel in their big brown Bentley, and Rinpoche and I got in the back seat. My aunt and uncle were in the front, and they proceeded to have an awful fight about how to get to the hotel where we were going to have drinks. In the middle of this, my aunt turned to me and said, "You know, marriage isn't easy under the best of circumstances. I don't know how you can expect this to work out."

My uncle ordered drinks for us at the bar. Rinpoche had whiskey, and given the circumstances, he drank a fair amount. My uncle tried to open a conversation with him, saying, "Well, now, do tell me about yourself. When did you become a priest?" Rinpoche answered, "Oh, I was a year old." Of course, this was incomprehensible to my uncle, and he began to sputter. He didn't know where to begin to get a handle on the whole situation. The conversation degenerated from there, and he and Rinpoche proceeded to get drunk. My uncle started yelling at him, calling him a cradle robber and a baby snatcher.

Then, seemingly out of the blue, my uncle looked across the street and said in his most arch English accent, "Well, there's a Chinese restaurant. That looks appropriate! Let's eat there." We all got up and walked across the street, which was not that easy for Rinpoche, who was still using a walker after his accident. My uncle seemed to have no idea that going to a Chinese restaurant would not necessarily be the most pleasant experience for a Tibetan. However, Rinpoche loved Chinese food and had no particular animosity toward the Chinese people as a whole. Nevertheless, my uncle's lack of sensitivity struck me as a reflection of his narrow-mindedness. To my uncle, one Oriental was the same as another regardless of whether they were Chinese, Japanese, Burmese, or Tibetan.

After we sat down at the restaurant, my uncle started yelling at the waiter, "Boy, boy, come over here." When the waiter came along, my uncle said, "Bring something Chinese!" The waiter said, "I'm very happy to bring you a menu, sir;' to which my uncle replied, "Just bring something Chinese. Anything Chinese. It's all the same anyway." Not surprisingly, nothing was resolved at dinner. Toward the end of the meal, my uncle said to Rinpoche, "Well, you'd better go to America. You'll do well in America, because anything goes there."

After this painful evening with my aunt and uncle, Rinpoche and I felt quite alienated from my family, and we thought about driving to Samye Ling the next day. \We had already decided that we would not be going back to the ugly scene at Garwald House.) However, the next morning, Tessa and her boyfriend Roderick arrived at our hotel. They had traveled to Samye Ling the day after the wedding, where they had spent the night. They told us that people there were having a terribly difficult time accepting the marriage and that we shouldn't return right away. We decided to take a short honeymoon to Findhorn, a spiritual community in northern Scotland. We invited Roderick and my sister to drive up with us. That day we drove all the way to Inverness, which was a beautiful drive through the landscape of northern Scotland, much of which reminded Rinpoche of Tibet. I remember sitting in the car as we went through the highlands, staring at Rinpoche, thinking, "I can't believe I'm married to you. This is amazing. I can't believe this has happened." I felt like the luckiest person in the world, even though the situation definitely had taken some bizarre twists and turns.

The Findhorn community is famous for growing huge vegetables in the rocky highland soil and for talking to the fairies. It was started by Peter Caddy and his wife Eileen, who greeted us when we arrived. Rinpoche and I were given a nicely appointed trailer, and Tessa and her boyfriend also stayed on the property. It was a brief but delightful honeymoon. We took walks around the property, and Peter Caddy showed us artwork done by people there, which had something to do with extraterrestrials.

While we were there, I consulted the I Ching, and I got "The Marrying Maiden," with the first line a changing line, which mentions "the lame man who is able to tread." I found this amusing, thinking of it literally as referring to Rinpoche and his difficulties walking. The line said that undertakings would bring good fortune.

During our time at Findhorn, I was introduced to Rinpoche's custom of waking up in the middle of the night wanting something to eat. He had this habit for years, for most of his life in the West, in fact. While we were at Findhorn, I got up every night and made him a sandwich.

We also visited an ancient Benedictine monastery nearby, Pluscarden Priory. After Rinpoche mentioned that he was a Tibetan lama, the monks were very interested in him, and they gave us a complete tour of the facilities. We attended services there and had an interview with the prior. Rinpoche particularly enjoyed the Gregorian chanting used in the service, as well as the sweet-smelling incense, and he purchased some to take back to Samye Ling. He felt the monks were following a valid contemplative tradition there and that they were practicing the heart of Christianity. He was quite impressed by their contemplative lifestyle and was inspired to see people practicing an authentic Christian monastic tradition.

At the priory, Rinpoche talked to the monks about his relationship with Thomas Merton, whom he had met in India in 1968, a short time before Father Merton's sudden death. They had drinks together in a bar in Calcutta and were quite taken with one another. Merton commented in the journal he kept at the time, "Chogyam Trungpa is a completely marvelous person. Young, natural, without front or artifice, deep, awake, wise. I am sure we will be seeing a lot more of each other." Rinpoche, looking back years later on their meeting, said of it, "I had the feeling that I was meeting an old friend, a genuine friend. In fact, we planned to work on a book containing selections from the sacred writings of Christianity and Buddhism. . .. He was the first genuine person I met from the West."1

After our visit to Pluscarden, Rinpoche and I discussed the Christian contemplative tradition. I think it was the first time we ever talked about the relationship between Christianity and Buddhism. We joked that our children could become Christians as their rebellion against their parents. I asked Rinpoche, "What would you do if one of our sons said he wanted to become a Christian priest?" And he said, "I would encourage him to become the best Christian priest that ever existed; he would have to do, it completely, fully." He certainly didn't feel that he had cornered the market on wisdom. He appreciated the wisdom and discipline in other traditions. I didn't have a very good impression of the Christian faith, based on my own repressive experiences, but he helped me to see that there was more to it than the conventional approach.

Our time at Findhorn came to an end all too quickly; and we reluctantly resolved to go to Samye Ling, not knowing what to expect. When we arrived there, we were pleasantly surprised to find that a very nice bedroom had been prepared for us. An elaborate thangka of the Buddha had been hung in our room, filling an entire wall. It was a gift to Rinpoche from the queen of Bhutan, Ashi Kesang, when he visited there in 1968. Having this magnificent painting in our bedroom gave me a feeling of acceptance. One of the young monks living at Samye Ling, Samten, presented us with the traditional Tibetan offering of white scarves, or khatas, and talked about the positive significance of our marriage. Superficially at least, there was a sense of being welcomed.

Although we tried to settle in at Samye Ling, almost immediately we began making plans for our departure. Rinpoche gave some thought to returning to live in Asia since things had become so difficult in Scotland. He had me write to a university in Hong Kong, asking if they had a teaching position for him. They wrote back and said that if he could teach Tibetan, they would like him to join the faculty. I convinced him, however, that this was not the direction we should go. He also had been talking about making a visit to America, to do a lecture tour and to receive additional medical care there. Several close students who had left Samye Ling were in the United States looking for land for a meditation center on the East Coast. I encouraged him to think about going to America as soon as possible.

We stayed at Samye Ling for about two-and-a-half months. While we were there, I took Tibetan lessons with one of the monks, Phende Rinpoche, and studied thangka painting with Sherab Palden Beru. He was always very warm toward me, and he adored Rinpoche. He had some initial difficulty with the idea of our marriage, but after he adjusted, he was very kind to both of us. Rinpoche spent most of his time in our room, although occasionally he would come down to the shrine room during the pujas, or religious services. During this period, he sometimes wore monks' robes, tied with a yellow sash to indicate that he was a married lama. I learned to help him dress. Because of the accident, he needed my help. Other times, he wore Western-style dress, men's trousers with a blue button-down shirt and a maroon cashmere sweater. In that era, even his Western clothing often had a little bit of monastic feeling. He loved to wear a turtleneck that was the color of a monk's saffron robe.

During this period, Rinpoche still had to wear a caliper, or a brace, for his left foot and lower leg, which I used to help him put on. When we were first married, he used a walker, but he soon graduated to a walking stick, and eventually he was able to walk just with the caliper. In the long run, he didn't even need that, although he always had orthopedic shoes specially made for him.

Akong would not allow Rinpoche to lecture at Samye Ling. It seemed to be a, control issue. Rinpoche, however, did travel to other parts of Britain to teach. Once he was invited to speak at Bristol University. We stayed the night with an Indian family who was hosting the talk. Another time, we went down to Cambridge for Rinpoche to give a talk. We visited Ato Rinpoche and Alithea while we were there. Since meeting in India, Trungpa Rinpoche and Ato Rinpoche had remained close colleagues and friends. Perhaps because Ato Rinpoche had experienced obstacles to his marrying an Englishwoman, he and his wife were very understanding of our situation.

Since Rinpoche could not give talks· or group teachings at Samye Ling, most of his personal contact with students was in the form of private interviews, which were held in our room. He often set aside several hours a day for interviews. During that time, I practiced meditation, worked on my thangka painting, or handled Rinpoche's correspondence for him. We were preparing for the celebration of Losar, the Tibetan New Year, which would occur that year in early February, and I helped address New Year's cards for Rinpoche. Akong even gave me a typewriter and a place to work. A postcard came from a Mr. Karl Usow in Boulder, Colorado, inviting Rinpoche to visit there and teach at the University of Colorado. We both liked the mountains shown on the front of the card, and Rinpoche said it reminded him of the mountains in Tibet. I wrote back to Karl on Rinpoche's behalf, saying that we would try to come to Colorado for a visit.

One morning at Samye Ling, Rinpoche's interviews went on much longer than expected. Finally, I returned to our room to see what was up. I walked in on him passionately embracing a young woman. I was devastated. I locked myself in our bathroom and sat on the floor crying for hours. I didn't know what to do. I wondered if! should leave Rinpoche. He kept knocking on the bathroom door, but I repeatedly told him to go away.

After several hours, I came out, and we talked. Rinpoche was very sweet. He didn't seem to be avoiding or concealing anything, neither did he seem embarrassed. In some respects, it was an absolutely intimate and direct moment. He said that our connection was very deep and important to him. He told me openly that he expected that he was going to have intimate relationships with some of his female students, but that it didn't mean there was a problem with our relationship. Rinpoche said that in fact it was only because he had such trust in our relationship that he felt it would be possible for him to have these other relationships.

This is a very personal example, from my own life, of Rinpoche's truthfulness. He never lied to me about what he was doing. He was quite willing to talk about what had happened. The communication was so direct and real that I felt I could relax, and I started to let go of my conventional reference points. Rinpoche and I were deeply in love, and I didn't feel that he was using another relationship to blackmail me emotionally in some way.

On a fundamental level, Rinpoche was the most loyal husband I can imagine. In fact, our relationship went much deeper than many conventional marriages. My heart connection with him went far beyond the issue of sexuality, and I knew this from these very early times. As time went on, I felt that many relative difficulties were not fundamental problems -- if I let myself feel that deeper connection.

Although I had the formality of marriage with Rinpoche, my union with him was unique. We called it marriage, whatever it was, but Rinpoche was much too big a personality to trap into a monogamous relationship. It just couldn't be. Rinpoche was not an ordinary husband. He was not an ordinary man. I couldn't be possessive of him. I know that this may be difficult for people to accept, but it is my experience.

His life was dedicated to working with other people and their state of mind. In answering a letter from a student in 1971, he wrote: "I work with people -- that seems to be my reason for existence."2 I came to feel that if that sometimes carried over into sexual intimacy, that was okay. I never felt these relationships were an exploitation of his students. It was a way for him to create further intimacy with people. From a broad perspective, I came to realize that Rinpoche definitely was not here on this earth solely to be my sexual partner. It was not always easy or pleasant for me to accept this, but it was really okay.

In Rinpoche's monastery, the monks did a chant invoking the incarnations of the Trungpas, of which Rinpoche was the eleventh. Rinpoche's students in the West now do this chant as well. There is one stanza for each new Trungpa. In the stanza for the Eleventh Trungpa -- my husband -- he is compared to the Mad Yogi of Bhutan, a revered teacher who lived in the nineteenth century. He was famous both for the depth of his wisdom and for being very wild-drunken and bawdy. This was a very unusual reference because the other Trungpas were generally saintly monks, quite reserved in their behavior. This lineage supplication was written when Rinpoche was about ten years old, so it must somehow have been obvious to the revered lama who wrote this text that this Trungpa would be an unconventional person, another mad yogi.

In fact, Rinpoche's sexual experiences began before he left Tibet. A little while after we were married, I had a dream that he had a daughter in Tibet. I woke up and I said, "I had this ridiculous dream." "Oh," he said when I told him the dream, "It might be true." Then he told me about a night he spent with a Tibetan princess. He was in a procession with a beautiful princess from an outlying area, and he became infatuated with her. He managed to get close to her and suggested that she climb in through his window that night. She did, and they slept together. Before leaving Tibet, Rinpoche saw her again at some public event and she was clearly pregnant. So he might have had a daughter somewhere in Tibet.

As much as I appreciated my husband, I wasn't always accepting of his behavior. When we were first married, Rinpoche told me that it was normal for Tibetan men to beat their wives. I told him this was barbaric, but he said that it was just common practice. In the first few months of our marriage, he tried -- not very convincingly -- to slap me a couple of times when we were arguing. I said to him, "What do you think you're doing?" And he said to me, "This is just what Tibetans do." I felt that this was definitely not okay. I waited until he was asleep one day, and I took his walking stick and began hitting him as hard as I could. He woke up, and he was quite shocked, and he said, "What are you doing?" I said, "This is just what Western women do." He got the message, and it was never an issue again.

If you think about it, Rinpoche had no idea how to be a husband. He went to live in a monastery when he was thirteen months old, and although his mother came and stayed nearby until he was five, he had virtually no experience of family life. His role models were his gurus, and he had great examples in that area. He grew up as a monk, a student, and a Buddhist teacher, but he had to learn what it meant to be a householder, a husband, and a father.

In fact, at the time that we married, Rinpoche's seven-year-old son, Osel Mukpo, was living at Samye Ling. When Rinpoche visited India and Bhutan in 1968, he told Konchokla, Osel's mother, that he wanted to bring their son back to Scotland to live with him. It took a while to arrange this, but eventually he was able to come over. The first time I saw Osel at Samye Ling, I was struck by his physical beauty and small stature, the latter probably a result of malnutrition in India. He was very shy and spoke only Tibetan at the time. I remember him going off to his first day in kindergarten in a jeep with a local Scottish fellow, Mr. McTaggert. This beautiful, small, and very shy child was sobbing as the car left.

Osel arrived in England around the time of Rinpoche's accident. They had a very affectionate relationship, although Osel was shy around his father, understandably so. Rinpoche had asked the monks to look after his son while he was recuperating at Garwald House, since he was in no position to personally care for his son. When we arrived at Samye Ling after the wedding, Osel was living in the monks' quarters. In addition to attending the local school, he was being tutored in literary Tibetan by Akong and the other monks. They were apparently very rough with him. It seemed to be some sort of archaic method of Tibetan education.

Soon after I married Rinpoche, Osel had a high fever, and the monks put him to bed with no pajama top on. I felt that this was not the proper thing to do, so I asked one of the monks to put a top on him. The monk replied, "Oh no, it's good ifhe's cold. He'll get rid of the fever quickly." At that point, I said, "This is enough," and I got an extra mattress and moved him into our bedroom with us. He stayed in our room with us until we left for America.

In general, Rinpoche and I were very isolated from others during this period. Few of Rinpoche's close students remained at Samye Ling. Josie Wechsler, the English nun, was devoted to Rinpoche, and a few other close students were still around. A few friends would occasionally visit or invite us over, such as Ato Rinpoche and Alithea. Stash and Amalie lived nearby; and we would get together with them sometimes. Maggie Russell, whom Rinpoche had wanted to marry, came to visit once. I thought it was great that she had her own car. We spent a great deal of time alone, however, and there was a terrible underlying atmosphere of aggression toward us at Samye Ling.

During this time, Rinpoche's relationship with Akong continued to degenerate. In addition to their disagreement over the presentation of Buddhism in the West, there were other points of contention. Rinpoche was quite disappointed with how Akong related to the mental illness of one of the young monks at Samye Ling. He had to be hospitalized because of a nervous breakdown. Rinpoche felt that, rather than working with this person, Akong's main concern seemed to be to hide the situation from everyone. Rinpoche and I went to visit this monk in the mental hospital.

Akong was terribly mean to me. He put me on the work schedule to do dinner dishes almost every night. If he didn't like the way I did the dishes, he would knock on the bedroom door and tell me to come down and do them again. It felt like a humiliation tactic. This, of course, added to the tension that was building between Rinpoche and Akong.