by Wikipedia

Accessed: 3/27/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

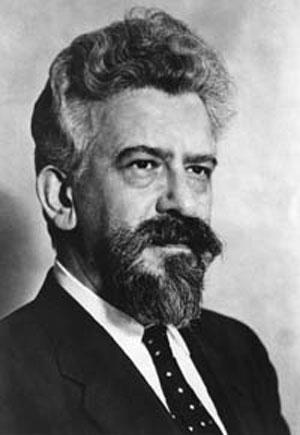

William Sloane Coffin

Photo of The Rev. William Sloane Coffin, Jr. (1924-2006), Senior Minister of The Riverside Church, New York, NY (1977-87)

Coffin circa 1980

Church: United Church of Christ

Other posts: Riverside Church

Orders

Ordination: Presbyterian church

Personal details

Birth name: William Sloane Coffin Jr.

Born: June 1, 1924

Died: April 12, 2006 (aged 81)

Nationality: American

Denomination: Presbyterian, United Church of Christ

Spouse: Eva Rubinstein, Harriet Gibney, Virginia Randolph Wilson

Education: Yale College, Union Theological Seminary

Alma mater: Yale Divinity School

William Sloane Coffin Jr. (June 1, 1924 – April 12, 2006) was an American Christian clergyman and long-time peace activist. He was ordained in the Presbyterian Church, and later received ministerial standing in the United Church of Christ. In his younger days he was an athlete, a talented pianist, a CIA officer, and later chaplain of Yale University, where the influence of Reinhold Niebuhr's social philosophy led him to become a leader in the Civil Rights Movement and peace movements of the 1960s and 1970s. He also was a member of the secret society Skull and Bones. He went on to serve as Senior Minister at the Riverside Church in New York City and President of SANE/Freeze (now Peace Action), the nation's largest peace and social justice group, and prominently opposed United States military interventions in conflicts, from the Vietnam War to the Iraq War. He was also an ardent supporter of gay rights.

Biography

Childhood

William Sloane Coffin Jr. was born into the wealthy elite of New York City. His paternal great-grandfather William Sloane was a Scottish immigrant and co-owner of the very successful W. & J. Sloane Company. His uncle was Henry Sloane Coffin, president of Union Theological Seminary and one of the most famous ministers in the U.S. His father, William Sloane Coffin, Sr. was president of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and an executive in the family business.[1]

His mother, Catherine Butterfield, had grown up in the Midwest, and as a young woman spent time in France during World War I providing relief to soldiers, and met her future husband there, where he was also engaged in charitable activities. Their three children grew up fluent in French by being taught by their nanny, and attended private schools in New York.

William Sr.'s father, Edmund Coffin, was a prominent lawyer, real estate developer, and reformer who owned a property investment and management firm that renovated and rented low-income housing in New York. Upon Edmund's death in 1928, it went to his sons William and Henry, with William managing the firm. When the Great Depression hit in 1929, William allowed tenants to stay whether or not they could pay the rent, quickly draining his own funds, and at a time when the family's substantial W. & J. Sloane stock was not paying dividends.

William Sloane Coffin, Sr. died at home on his oldest son Edmund's eleventh birthday in 1933 from a heart attack he suffered returning from work. After this, his wife Catherine decided to move the family to Carmel, California, to make life more affordable, but was able to do this only with financial support from her brother-in-law Henry. After years spent in the most exclusive private schools in Manhattan, the three Coffin children were educated in Carmel's public schools, where William had his first sense that there was injustice—sometimes very great—in the world.

A talented musician, he became devoted to the piano and planned a career as a concert pianist. At the urging of his uncle Henry (who was still contributing to the family's finances), his mother enrolled him in Deerfield Academy in 1938.

The following year (when Edmund left for Yale University), William moved with his mother to Paris at the age of 15 to receive personal instruction in the piano and was taught by some of the best music teachers of the 20th century, including Nadia Boulanger. The Coffins moved to Geneva, Switzerland, when World War II came to France in 1940, and then back to the United States, where he enrolled in Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts.

Early adulthood

Having graduated from high school in 1942, William enrolled at Yale College and studied in the School of Music. While continuing his pursuit of the piano, he was also excited by the prospect of fighting to stop fascism and became very focused on joining the war effort. He applied to work as a spy with the Office of Strategic Services in 1943, but was turned down for not having sufficiently "Gallic features" to be effective. He then left school, enlisted in the Army, and was quickly tapped to become an officer. After training, he was assigned to work as liaison to the French and Russian armies in connection with the Army's military intelligence unit, and where he heard first-hand stories of life in Stalin's USSR.

After the war, Coffin returned to Yale, where he would later become President of the Yale Glee Club. Coffin had been a friend of George H. W. Bush since his youth, as they both attended Phillips Academy (1942). In Coffin's senior year, Bush brought Coffin into the exclusive Skull and Bones secret society at the university.

Upon graduating in 1949, Coffin entered the Union Theological Seminary, where he remained for a year, until the outbreak of the Korean War reignited his interest in fighting against communism. He joined the CIA as a case officer in 1950 (his brother-in-law Franklin Lindsay had been head of the Office of Policy Coordination at the OSS, one of the predecessors of the CIA) spending three years in West Germany recruiting anti-Soviet Russian refugees and training them how to undermine Stalin's regime.[1] Coffin grew increasingly disillusioned with the role of the CIA and the United States due to events including the CIA's involvement in overthrowing Prime Minister Mohammed Mossadegh of Iran in 1953, followed by the CIA's orchestration of the coup that removed President Jacobo Árbenz in Guatemala in 1954.

Ministry and political activism

After leaving the CIA, Coffin enrolled at Yale Divinity School and earned his Bachelor of Divinity degree in 1956, the same year he was ordained a Presbyterian minister. This same year he married Eva Rubinstein, the daughter of pianist Arthur Rubinstein, and became chaplain at Williams College. Soon, he accepted the position as Chaplain of Yale University, where he remained from 1958 until 1975. Gifted with a rich bass-baritone voice, he was an active member of the Yale Russian Chorus during the late 1950s and 1960s.

With his CIA background, he was dismayed when he learned in 1964 of the history of French and American involvement in South Vietnam. He felt the United States should have honored the French agreement to hold a national referendum in Vietnam about unification. He was in early opposition to the Vietnam War and became famous for his anti-war activities and his civil rights activism. Along with others, he was a founder in the early 1960s of the Clergy and Laity Concerned About Vietnam, organized to resist President Lyndon Johnson's escalation of the war.[1]

Coffin had a prominent role in the Freedom Rides challenging segregation and the oppression of black people. As chaplain at Yale in the early 1960s, Coffin organized busloads of Freedom Riders to challenge segregation laws in the South. Through his efforts, hundreds of students at Yale University and elsewhere were recruited into civil rights and anti-war activity. He was jailed many times, but his first conviction was overturned by the Supreme Court.[1]

In 1962, he joined SANE: The Committee for a SANE Nuclear Policy,[2] an organization he would later lead.[3]

Approached by Sargent Shriver in 1961 to run the first training programs for the Peace Corps, Coffin took up the task and took a temporary leave from Yale, working to develop a rigorous training program modeled on Outward Bound and supervising the building of a training camp in Puerto Rico. He used his pulpit as a platform for like-minded crusaders, hosting the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., South African Archbishop Desmond Tutu, and Nelson Mandela, among others. Fellow Yale graduate Garry Trudeau has immortalized Coffin (combined with Coffin's protege Rev. Scotty McLennan) as "the Rev. Scot Sloan" in the comic strip Doonesbury. During the Vietnam War years, Coffin and his friend Howard Zinn often spoke from the same anti-war platform. An inspiring speaker, Coffin was known for optimism and humor: "Remember, young people, even if you win the rat race, you're still a rat."[4]

By 1967, Coffin concentrated increasingly on preaching civil disobedience and supported the young men who turned in their draft cards. He was, however, uncomfortable with draft-card burning, worried that it looked "unnecessarily hostile".[5][6] Coffin was one of several persons who signed an open letter entitled "A Call to Resist Illegitimate Authority", which was printed in several newspapers in October 1967. In that same month, he also raised the possibility of declaring Battell Chapel at Yale a sanctuary for resisters, or possibly as the site of a large demonstration of civil disobedience. School administration barred the use of the church as a sanctuary. Coffin later wrote, "I accused them of behaving more like 'true Blues than true Christians'. They squirmed but weren't about to change their minds.... I realized I was licked."[7]

And so on January 5, 1968, Coffin, Dr. Benjamin Spock (the pediatrician and baby book author who was also a Phillips Academy alumnus), Marcus Raskin, and Mitchell Goodman (all signers of "A Call to Resist Illegitimate Authority" and members of the anti-war collective RESIST[8]) were indicted by a Federal grand jury for "conspiracy to counsel, aid and abet draft resistance". All but Raskin were convicted that June, but in 1970 an appeals court overturned the verdict. Coffin remained chaplain of Yale until December 1975.[1]

In 1977, he became senior minister at the Riverside Church—an interdenominational congregation affiliated with both the United Church of Christ and American Baptist Churches—and one of the most prominent congregations in New York City. He was a controversial, yet inspirational leader at Riverside. He openly and vocally supported gay rights when many liberals still were uncomfortable with homosexuality. Some of the congregation's socially conservative members openly disagreed with his position on sexuality.[1]

Nuclear disarmament

Coffin started a strong nuclear disarmament program at Riverside, and hired Cora Weiss (a secular Jew he had worked with during the Vietnam War and had traveled with to North Vietnam in 1972 to accompany three released U.S. prisoners of war), an action which was uncomfortable for some parishioners. Broadening his reach to an international audience, he met with numerous world leaders and traveled abroad. His visits included going to Iran to perform Christmas services for hostages being held in the U.S. embassy during the Iran hostage crisis in 1979 and to Nicaragua to protest U.S. military intervention there.

In 1987, he resigned from Riverside Church to pursue disarmament activism full-time, saying then that there was no issue more important for a man of faith. He became president of SANE/FREEZE[9] (now Peace Action), the largest peace and justice organization in the United States. He retired with the title president emeritus in the early 1990s, and then taught and lectured across the United States and overseas. Coffin also wrote several books. He cautioned that we are all living in "the shadow of Doomsday", and urged that people turn away from isolationism and become more globally aware. Shortly before his death, Coffin founded Faithful Security, a coalition for people of faith committed to working for a world free of nuclear weapons.[1]

Personal life

Coffin was married three times. His first two marriages, to Eva Rubinstein and Harriet Gibney, ended in divorce. He was survived by his third wife, Virginia Randolph Wilson (called "Randy").[10] Eva Rubinstein, his first wife and the mother of his children, was a daughter of pianist Arthur Rubinstein. The loss of their son Alexander in a car accident in 1983 inspired one of Coffin's most requested sermons.

He was given only six months to live in early 2004 due to a weakened heart. Coffin and his wife lived in the small town of Strafford, Vermont, a few houses away from his brother Ned, until his death nearly two years later at age 81.

Military awards

• American Campaign Medal

• European-African-Middle Eastern Campaign Medal

• World War II Victory Medal

• Army of Occupation Medal with "Germany" clasp

Books

By Coffin

• Letters to a Young Doubter, Westminster John Knox Press, July 2005, ISBN 0-664-22929-8

• Credo, Westminster John Knox Press, December 2003, ISBN 0-664-22707-4

• The Heart Is a Little to the Left: Essays on Public Morality, Dartmouth College, 1st edition, October 1999, ISBN 0-87451-958-6

• The Courage to Love, sermons, Harper & Row, 1982, ISBN 0-06-061508-7

• Once to Every Man: A Memoir, autobiography, Athenaeum Press, 1977, ISBN 0-689-10811-7

About Coffin

• William Sloane Coffin, Jr.: A Holy Impatience, by Warren Goldstein, Yale University Press, March 2004, ISBN 0-300-10221-6

• The Trial of Dr. Spock, William Sloane Coffin, Michael Ferber, Mitchell Goodman, and Marcus Raskin, by Jessica Mitford, New York, Knopf, 1969 ISBN 0-394-44952-5

See also

• List of peace activists

References

1. Goldstein, Warren. William Sloane Coffin Jr.: A Holy Impatience (2005).

2. "Service for William Sloane Coffin to be Held at Yale". Yale News. Retrieved 2017-02-12.

3. Charney, Marc D. (2006-04-13). "Rev. William Sloane Coffin Dies at 81; Fought for Civil Rights and Against a War". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 2017-02-12.

4. Rick Perlstein (2015). The Invisible Bridge: The Fall of Nixon and the Rise of Reagan. Simon and Schuster. p. 131.

5. “Interview with William Sloane Coffin, 1982.”, August 30, 1982. WGBH Media Library & Archives. Retrieved November 9, 2010.

6. Foley, M.S. (2003). Confronting the War Machine: Draft Resistance During the Vietnam War. University of North Carolina Press. p. 120. ISBN 978-0-8078-5436-5.

7. Geoffrey Kabaservice (2005). The Guardians: Kingman Brewster, His Circle, and the Rise of the Liberal Establishment. Henry Holt. p. 320.

8. Barsky, Robert F. Noam Chomsky: a life of dissent (M.I.T. Press, 1998) online Archived 2013-01-16 at the Wayback Machine

9. SANE: The Committee for a SANE Nuclear Policy merged with the Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign in 1987 and was renamed SANE/FREEZE; it was renamed Peace Action in 1993.

10. Schudel, Matt; Bernstein, Adam (April 16, 2006). "The Rev. William Sloane Coffin made his mark as activist, rebel". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 2017-02-12.

Sources

• Once to Every Man: A Memoir (1977)

• William Sloane Coffin, Jr.: A Holy Impatience (2004)

• Passion for the Possible: A Message to U.S. Churches

External links

• Interview from 1982 with William Sloane Coffin on Vietnam and the Anti-War movement WGBH Educational Foundation

• A Politically Engaged Spirituality Video and transcript of Coffin's April 2005 speech at Yale Divinity School

• Interview with William Sloane Coffin from Religion & Ethics Newsweekly, August 2004

• William Sloane Coffin: A Lover's Quarrel With America Video interview from Old Dog Documentaries

• William Sloane Coffin - Not to Bring Peace, But a Sword Sermon and interview.

• A film clip "The Open Mind - A Man for All Seasons (1986)" is available at the Internet Archive

• Profile of Coffin from Yale Alumni Magazine, March 2004

• Personal papers archive at Yale University

• Selected writings (PDF)

• Peace Action (formerly SANE/Freeze, the merger of SANE and the Nuclear Weapons Freeze Campaign)

• Faithful Security

• http://www.williamsloanecoffin.org This is the complete digital collection of William Sloane Coffin's sermons preached from the pulpit of New York City's Riverside Church 1977–1987.

• Speech "Who Is the Enemy?" delivered April 8, 1983 at a symposium in Kansas City.

Memorials

• Obituary from the New York Times

• Obituary from the Los Angeles Times

• Obituary from The Guardian

• Obituary from the Associated Press

• Remembrance from the United Church of Christ (article and video)

• Remembrance from The Nation

• Remembrance by William F. Buckley Jr. in the Yale Daily News

• The Legacy of William Sloane Coffin by Rev. Scotty McLennan

• Tribute of Yale Class of 1968 to its "Permanent Chaplain "

• Obituary on Commondreams.org

• Photo gallery of Coffin from The Washington Post