Part 1 of 2

“You Don’t Exist”. Arbitrary Detentions, Enforced Disappearances, and Torture in Eastern Ukraineby Human Rights Watch

July 21, 2016

https://www.hrw.org/report/2016/07/21/y ... re-eastern

© 2016 Human Rights Watch cover illustration with two men tied up

SummaryIn April 2015, Vadim, 39, was traveling on a shuttle bus home to Donetsk, the capital of the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic in eastern Ukraine. He had boarded in Slovyansk, which is under Ukrainian government control. At a checkpoint manned by Ukrainian forces, a gunman ordered him off the bus. Armed men in camouflaged uniforms without insignia tied Vadim’s hands behind his back, pulled a bag over his head, pushed him to his knees, calling him a “separatist thug,” and questioned him about his connections in Slovyansk. Then, they threw him into the back seat of a car and drove off to a base full of armed people, where he was kept in unacknowledged detention for three days, interrogated, and tortured. Then, his captors transferred him to another unlawful detention facility, apparently maintained by Ukraine’s Security Service (SBU) personnel. Vadim spent another six weeks there inunacknowledgeddetentionwithout any contact with the outside world. During his time in captivity, Vadim’s interrogators tortured him with electric shocks, burned him with cigarettes, and beat him, demanding that he confess to working for Russia-backed separatists. Finally, they released him. Vadim returned to Donetsk and was immediately detained by local de facto authorities, who suspected him of having been recruited by the SBU during his time in captivity. He spent over two months in incommunicado detention in an unofficial prison in central Donetsk where his captors, again, beat and ill-treated him.

Both the Ukrainian government authorities and Russia-backed separatists in eastern Ukraine have held civilians in prolonged, arbitrary detention, without any contact with the outside world, including with their lawyers or families. In some cases, the detentions constituted enforced disappearances, meaning that the authorities in question refused to acknowledge the detention of the person or refused to provide any information on their whereabouts or fate. Most of those detained suffered torture or other forms of ill-treatment. Several were denied needed medical attention for the injuries they sustained in detention.

In cases documented by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, the Ukrainian authorities and pro-Kyiv paramilitary groups detained civilians suspected of involvement with or supporting Russia-backed separatists, while the separatist forces have detained civilians suspected of supporting or spying for the Ukrainian government. Vadim’s case stands out because, of all the people we interviewed, he was the only one who was held in secret detention and tortured first by one side, then the other.

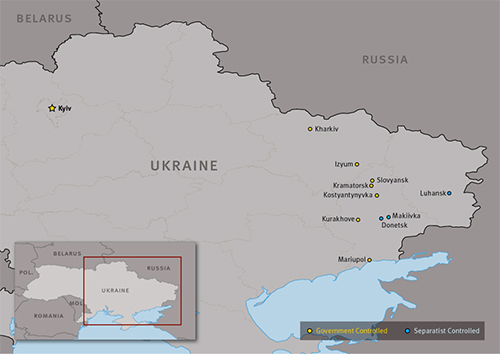

Map of Ukraine

Map of UkraineAmnesty International and Human Rights Watch investigated in detail nine cases of arbitrary, prolonged detention of civilians by the Ukrainian authorities in informal detention sites and nine cases of arbitrary, prolonged detention of civilians by Russia-backed separatists. This report details cases that took place mostly in 2015 and the first half of 2016.

Persons held by the warring sides in eastern Ukraine are protected under international human rights and international humanitarian law, which unequivocally ban arbitrary detention, torture, and other ill-treatment. International standards provide that allegations of torture and other ill-treatment be investigated, and that, when the evidence warrants it, the perpetrators be prosecuted. Detainees must be provided with adequate food, water, clothing, shelter, and medical care.

In almost all of the eighteen cases investigated, release of the civilian detainees was at some point discussed by the relevant side in the context of prisoner exchanges. In nine out of the eighteen cases, they were in fact exchanged. This gives rise to serious concerns that both sides may be detaining civilians in order to have “currency” for potential exchange of prisoners.

It is difficult to estimate the total number of civilians who have been the victims of the kinds of abuses documented in this report. However,

the Report on the human rights situation in Ukraine 16 February to 15 May 2016 published in June 2016 by the United Nations Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights (OHCHR) stated that “arbitrary detention, torture and ill-treatment remain deeply entrenched practices” in the region, suggesting that these problems are more widespread than the limited number of cases investigated by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch.

Violations by the Ukrainian authorities In most of the nine cases Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch investigated, pro-government forces, including members of so-called volunteer battalions, initially detained the individuals and then handed them over to the Security Service of Ukraine (SBU), who eventually moved them into the regular criminal justice system. Some were later exchanged for persons held by separatists and others released without trial.

In three cases detailed in this report the SBU allegedly continued the enforced disappearances, keeping the individuals in unacknowledged detention for periods ranging from six weeks to 15 months. One individual was exchanged, the other two simply released without trial. With regard to two of the individuals, there is no record whatsoever of their detention.

The June 2016 UN report noted that the cases of incommunicado detention and torture brought to their attention in late 2015 and early 2016 “mostly implicate SBU” and specifically mentioned the SBU compound in Kharkiv as an alleged place of unofficial detention.

Based on the research findings detailed in this report, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch believe unlawful, unacknowledged detentions have taken place in SBU premises in Kharkiv, Kramatorsk, Izyum, and Mariupol. We received compelling testimony from a range of sources, including recently released detainees, that as of June 2016 as many as 16 people remain in secret detention at the SBU premises in Kharkiv. Ukrainian authorities have denied operating any other detention facilities than their only official temporary detention center in Kyiv and denied having any information regarding the alleged abuses by SBU documented in this report.

Most interviewees told Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch they were tortured before their transfer to SBU’s facilities. Several also alleged that after being transferred to SBU premises they were, variously, beaten, subjected to electric shocks, and threatened with rape, execution, and retaliation against family members, in order to induce them to confess to involvement with separatism-related criminal activities or to provide information.

Abuses by Russia-backed separatists Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch documented nine cases in which Russia-backed separatists detained civilians incommunicado for weeks or months without charge, including as recently as early 2016, and, in most cases, subjected them to ill-treatment. Two of the individuals remain in custody as of this writing, their respective “trials” pending.

In the self-proclaimed Donetsk People’s Republic (DNR) and Luhansk People’s Republic (LNR), local security services operate with no checks and balances, detain individuals arbitrarily and hold them in their own detention facilities. Four of the individuals whose cases Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch documented were at some point transferred to remand prisons, where two of them were allowed access to a lawyer, but overall the vacuum of the rule of law in separatist-controlled areas deprives individuals held in custody of their rights and leaves them without recourse to any effective remedies.

Lack of access for independent monitorsIn May 2016, a delegation from the UN Subcommittee for Prevention of Torture cut short a visit to Ukraine because they were unable to access some of the detention sites, under both SBU and separatist control, they wanted to visit. Speaking of the SBU sites, the delegation chief, Malcolm Evans, stressed that the team was prevented from visiting "some places where we have heard numerous and serious allegations that people have been detained and where torture or ill-treatment may have occurred."

Separatist authorities have not responded to numerous requests by OHCHR for access to places of detention, and representatives of other international organizations that have expertise on rights protection in places of detention told Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International that they do not have access to places of detention in separatist-held areas. The Council of Europe High Commissioner for Human Rights, Nils Muižnieks, also noted in his report of a visit in March 2016 that relevant interlocutors in Donetsk told him that the “‘local legislation’ does not at present allow for this kind of supervision of the places of detention.”

Key recommendationsAmnesty International and Human Rights Watch call on the Ukrainian government and the de facto authorities in self-proclaimed DNR and LNR to immediately put an end to enforced disappearances and arbitrary and incommunicado detentions, and to launch zero-tolerance policies with regard to the torture and ill-treatment of detainees. All parties to the conflict must ensure that all the forces under their control are aware of the consequences of abusing detainees under international law, and that allegations of torture and ill-treatment in detention are thoroughly investigated and those responsible are held to account.

MethodologyThis report is based on the findings of joint research by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch, which included a one-week joint mission to separatist-controlled areas of Donetsk region in May 2016, two missions to government-controlled areas of Donetsk region in February and March 2016, as well as extensive desk research and interviews conducted in person in Kyiv or by phone and Skype.

Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch conducted a total of 40 interviews with victims of abuses, their family members, witnesses of abuses, victims’ lawyers, representatives of international organizations working in eastern Ukraine, Ukrainian government officials, representatives of the DNR, representatives of unofficial and official groups that are engaged in the negotiation of prisoner exchanges, and other sources.

All the interviews with victims were conducted after their release. Four of them asked Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch not to publish details of their cases for fear of reprisals but allowed use of the information they provided for background purposes and analysis. Our researchers spoke to all interviewees separately and in private in either Russian or Ukrainian. Wherever possible, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch also gathered medical records, legal documents, and photographs from alleged torture victims and family members of the individuals still in custody. Each interviewee was made aware of the purpose of the interview and agreed to speak on a voluntary basis. Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch did not provide interviewees any financial incentives to speak with us. Most interviewees chose to remain anonymous for fear of reprisals against themselves or members of their families or due to privacy concerns.

This report focuses exclusively on abuses against civilians. It does not include cases of arbitrary detention that concluded prior to spring 2015 (both organizations have extensively reported on arbitrary detention and torture in the region in 2014 and early 2015).[1]

During the joint research mission, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch met with the chief of staff for the Ombudsperson of the DNR.[2] The organizations’ delegates also sought to meet with the de facto Prosecutor’s Office but were denied a meeting.

On June 3, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch sent a letter to the head of the SBU summarizing some of our research findings, inquiring about SBU allegedly running unofficial prisons on its premises, and asking specific questions in connection with some of the documented cases. The SBU’s written reply, dated June 17, 2016, is cited in this report.[3]

I. Background: The Armed Conflict in Eastern UkraineThe 2014 “EuroMaydan” protests led to the February 21, 2014 ousting of Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych. Following Yanukovych’s ouster, Russian forces seized and eventually occupied Crimea. Around the same time, violence sporadically broke out in several cities and towns in eastern Ukraine between crowds of people supporting the protests in Kyiv and those opposed to it.

By mid-March, armed anti-government militia, initially calling themselves “self-defense units,” seized and occupied administrative buildings in several cities and towns in Donetsk and Luhansk regions. Their demands ranged from regional autonomy within a federated Ukraine, to full independence, to joining Russia.

In April 2014, separatist forces announced the establishment of the “Donetsk People’s Republic” (DNR) and the “Luhansk People’s Republic” (LNR) and established control, to various degrees, in and around several other cities, towns, and villages in the two regions.

In mid-April 2014, the Ukrainian State Security Service and Interior Ministry began counter-insurgency operations, which the government called an “anti-terrorist operation.” On May 11, anti-Kyiv groups proclaimed victory in the “referenda” they organized on the independence of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions.[4] On May 16, Ukraine’s First Deputy Prosecutor General Mykola Homosha announced that the “two self-proclaimed republics, the so-called Dоnetsk’s and Luhansk’s [people’s republics] are two terrorist organizations” under Ukrainian law.[5]

From the very beginning of the armed clashes, the Russian government made clear its political support for the separatists and clearly exercised influence over them. As hostilities continued into August, compelling evidence, including reports and satellite images from NATO and the capture of Russian soldiers within Ukraine, emerged that pointed to Russian forces’ direct involvement in military operations. Conflict between Russian and Ukrainian forces is an international armed conflict governed by the relevant rules of international humanitarian law.[6]

In February 2015, the internationally brokered Minsk II accords established a ceasefire, which significantly reduced hostilities, but frequent skirmishes along the frontline and exchanges of artillery fire have continued.

The conflict led to the complete collapse of law and order in the areas controlled by Russia-backed separatists. Separatist forces attacked, beat, and threatened anyone whom they suspected of supporting the Ukrainian government, including journalists, local officials, and political and religious activists, and carried out several summary executions.[7] They also subjected detainees to forced labor and kidnapped civilians for ransom, using them as hostages.[8]

Members of Ukrainian forces and paramilitaries also subjected detainees to torture and other ill-treatment and used detained civilians as pawns for prisoner exchanges between the warring sides.[9] Credible allegations emerged of torture and other egregious abuses by Ukraine’s so-called volunteer battalions Aidar[10] and Azov.[11] By spring 2015, most volunteer battalions had been formally integrated into the official chains of command in the Ministry of Defense or the National Guard of Ukraine. However, Right Sector, a prominent far-right movement, as well as some other groups have retained their paramilitary structures. Their members operate in close cooperation with the official Ukrainian forces on or near the frontline, but remain outside any official chain of command or accountability.[12]

Between April 2014 and May 2016, mortar, rocket, and artillery attacks killed over 9,000 people—including civilians, Ukrainian government forces, and anti-government forces—in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions and injured over 21,000.[13] Both separatist and government forces violated the laws of war by carrying out indiscriminate attacks in civilian-populated areas and placing civilian life at risk by not taking feasible precautionary measures when deploying artillery and other weaponry in or near civilian areas.[14]

In November 2014, the government of Ukraine withdrew social services support, including budgets for schools, hospitals, pensions, and social security, in separatist-controlled areas. Between July and December 2015, de facto authorities who exercised effective control over parts of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions denied authorization to most humanitarian agencies and human rights groups and expelled leading humanitarian groups from DNR and LNR.[15]

Prisoner ExchangesPrisoner exchanges are an important context for some of the abuses described in this report. One-off, unilateral releases and exchanges began early on in the conflict in eastern Ukraine. The warring parties agreed to exchange “all for all” as part of the February 2015 Minsk II accords.[16] However, there was never any clarity as to the true numbers and the identity of all those in the custody of either side. The warring parties’ figures and lists were at odds with each other. The undertaking to exchange “all for all” did not resolve this, although sporadic exchanges of smaller groups of prisoners continued. Each side continued to see it as an advantage to have more prisoners to “trade” with the other. Although Minsk II implied exchange primarily of combatants, in reality the process was extended to civilians, typically those alleged by their captors to be complicit in spying or similar activities on behalf of the other side. This has led to systematic abuse.

In several reports, the UN Human Rights Monitoring Mission for Ukraine (HRMMU) noted the persistent connection between arbitrary detention of civilians and prisoner exchanges. In February 2015, for example, it noted that “arbitrary detention of civilians regrettably remains a feature of the hostilities, including for the purpose of prisoner exchanges.”[17] Under international law the detention of civilians for the purpose of exchanges constitutes arbitrary detention but also hostage-taking, which is also clearly prohibited under international law.

Ukrainian law enforcement agencies have said their side was releasing “fighters suspected of terrorism or related crimes.”[18] In legal terms such “exchanges” constituted a problem. Effectively, there was no legal basis for exiting criminal suspects from official remand before the criminal proceedings against them were completed. It appears that this issue lies at the heart of some of the abuses described below, and is likely to be the reason some individuals have been held in unofficial, unacknowledged detention by the SBU: they could be exchanged without creating a paper trail and without having to resolve the arising legal complications.

II. Legal Framework

International Legal StandardsInternational humanitarian treaty law, as well as the rules of customary international humanitarian law, governs hostilities between the armed separatist groups and Ukrainian armed forces, as well as between Russian armed forces and Ukrainian forces. While there are differences in the sources and sometimes scope of the laws of war that apply to a non-international armed conflict and an international one, international humanitarian law is designed mainly to protect civilians and other non-combatants from the hazards of all forms of armed conflict, and applicable customary international humanitarian law reflects the large convergence of the two bodies of law that has taken place.

The conflict between the separatists—a non-state armed force—and Ukrainian forces is primarily a non-international armed conflict, which falls within the remit of Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and Protocol II relating to non-international armed conflicts, to which Ukraine is also a party. Protocol II provides further guidance on the fundamental guarantees for individuals during non-international conflicts to what is provided for in Common Article 3.[19]

Persons held by any party in connection with the armed conflict in eastern Ukraine are protected under international human rights and international humanitarian law. In both of these bodies of law, the ban on torture and other ill-treatment is one of the most fundamental prohibitions. Both Common Article 3 of the Geneva Conventions of 1949 and Protocol II require that anyone in the custody of a party to the conflict be protected against “violence to life of persons,” in particular murder, mutilation, and torture.[20] The provisions also bar “outrages upon personal dignity, in particular humiliating and degrading treatment.” Similarly, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR)[21] and the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR)[22] specifically bar torture and cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment.[23]

Torture is also a war crime under international humanitarian law in all conflicts.[24] Both international human rights law and international humanitarian law require that cases of torture and other ill-treatment be investigated, and that, when the evidence warrants it, the perpetrators be prosecuted. Detainees must be provided with adequate food, water, clothing, shelter, and medical care.

International humanitarian law acknowledges that during times of armed conflict there may be security grounds for temporary detention of civilians, but arbitrary detention is always prohibited, and parties to an armed conflict are required to ensure a legal basis and framework as well as basic safeguards for the detention of civilians. Grounds for detention must be legitimate and nondiscriminatory. Under customary international humanitarian law, detaining parties must adhere to certain procedures; for example, they are obligated to bring a person arrested on a criminal charge promptly before a judicial authority, and to allow the person to challenge the lawfulness of the detention.[25] Under human rights law, which applies even during armed conflict, persons in the custody of the state are entitled to judicial review of the legality of their detention.[26]

Enforced disappearances are serious crimes under international law and are prohibited at all times under both international human rights law and international humanitarian law. The prohibition also entails a duty to investigate cases of alleged enforced disappearance and prosecute those responsible.[27]An enforced disappearance occurs when someone is deprived of their liberty by agents of the state or persons acting with the state’s authorization, support or acquiescence, followed by a refusal to acknowledge the deprivation of liberty or by concealment of the fate or whereabouts of the disappeared person, placing that person outside the protection of the law.[28] Ukraine became a party to the International Convention on Enforced Disappearances on August 14, 2015. The Convention codifies the prohibition on enforced disappearances and, among other things, sets out the obligations of states to prevent, investigate, and prosecute all cases of enforced disappearances.

The ECHR and the ICCPR allow state parties to derogate from certain articles—in other words, to limit certain rights during emergency situations, including an armed conflict. In May 2015, Ukraine derogated from a number of articles in both conventions, including, as relevant to this report, articles relating to the right to liberty and security and fair trial in relation to terrorism suspects.[29] But the treaties also require any restrictions to be necessary, proportionate and non-discriminatory. Secretary General of the Council of Europe Thorbjørn Jagland issued a statement that the derogation “does not mean that Ukraine is no longer bound by the European Convention on Human Rights” and that the European Court of Human Rights will assess in each case whether the derogation is justified.”[30]

Ukrainian lawUkrainian law categorically prohibits torture.[31]

According to the Ukrainian Criminal Procedure Code, the authorities can detain a suspect for up to 72 hours without official charges, after which a court has to approve detention in a pre-trial detention facility with an official warrant or release the suspect. Detainees have the right to be informed of the allegations or charges against them and to challenge their arrest in court. However, following the conflict in eastern Ukraine, on August 12, 2014, parliament introduced special amendments into Ukraine’s law “on combatting terrorism” extending the period for which suspects accused of terrorism can be detained without charge to 30 days. The decision to detain a person beyond 72 hours lies with law enforcement, and a copy of the “preventative detention warrant,"endorsed by a prosecutor, is sent to a judge with a request to hold a custody hearing, which can take place at any time up to 30 days.[32]This was the subject of the above-mentioned derogations from the ECHR and ICCPR.[33] The potential for a person to be detained for up to 30 days before they are brought before a judge violates the ECHR.While the European Court of Human Rights has yet to rule on this provision, it has held that detention without being brought before a judge for 14 days, even with a derogation, violates the convention.The Court, acknowledging there was a legitimate state of emergency and derogation, held “it cannot accept that it is necessary to hold a suspect for fourteen days without judicial intervention.” It noted that the period was exceptionally long, and leaves detainees vulnerable to arbitrary detention and torture.[34]

Pre-trial detention is allowed only in pre-trial detention centers belonging to the State Penitentiary Service and disciplinary cells of the Ukrainian Armed Forces. In “certain cases,” the law permits short-term detention of suspects “in temporary detention facilities for the purpose of conducting investigative activities.[35] According to article 38 of the Ukrainian Criminal Procedures Code, bodies with investigative authority in Ukraine are the National Police (part of the Ministry of Interior system), the SBU, the Tax Police (part of the State Fiscal Service), and the State Investigation Bureau.[36] In reality, only the Ministry of Interior and the SBU operate temporary detention facilities. They are governed according to internal orders and guidelines.

Ukraine’s SBU stated in a letter to Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch that it has only one such facility, located in Kyiv.[37] According to the SBU’s Internal Guidelines on Temporary Detention Facilities, the maximum period of detention in this facility should not exceed 10 days.[38] Ukrainian law allows SBU officials to bring in people for questioning, but a questioning session can last no longer than eight hours per day and no investigative activities, including questioning, can be carried out from 10 p.m. to 6 a.m.[39]

Pre-trial detention in other remand facilities cannot exceed six months for minor crimes and up to 12 months for serious crimes, among them those that are terrorism-related.[40]

III. Enforced Disappearances, Arbitrary Detentions, and Torture by Members of the Ukrainian Authorities and ParamilitariesAmnesty International and Human Rights Watch investigated nine cases in which members of the Ukrainian authorities and paramilitaries held civilians in prolonged, secret captivity. Three of these—the most recent and egregious—are detailed below. Details of two others are withheld at the request of the victims, who fear retaliation. The remaining four are not detailed here as they pertain to arbitrary detentions that concluded prior to spring 2015.[41]

In most of the nine cases, pro-government forces, including members of so-called volunteer battalions, detained the individuals and handed them over to the SBU, which eventually moved them into the regular criminal justice system; some were later exchanged for persons held by separatists and others were released without trial.

In the three cases summarized in detail below, the SBU went on to hold these individuals from between six weeks and 15 months, without allowing them to see a lawyer or have any contact with the outside world. All of the individuals were suspected of involvement in pro-separatist activities.

The captivity involved periods during which they were forcibly disappeared or subjected to prolonged incommunicado detention. Most interviewees said they were tortured before their transfer to SBU’s facilities. Several also alleged that after being transferred to SBU premises they were beaten, subjected to electric shocks, and threatened with rape, execution, and retaliation against family members.

Most of the captives held by the Ukrainian authorities were eventually brought before a judge and moved into the regular criminal justice system.[42] However, they did not stand trial but were at some point released as part of prisoner exchanges between the warring sides. In these cases a judge released them on their own recognizance and an undertaking not to leave their place of permanent residence, pending the investigation. This arrangement enabled the authorities to remove them from state custody for the purpose of exchange; however, the individuals would face arrest upon return to government-controlled territory.

Those interviewed by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch have described the SBU buildings in Kharkiv, Kramatorsk, Izyum, and Mariupol where they were held in terms that indicate these were places of unlawful, unacknowledged detention. There are well-founded concerns that some persons continue to be victims of enforced disappearances and are being detained at the Kharkiv SBU compound. Two of those who were held for months at the Kharkiv SBU separately made lists of 16 other individuals (15 males and one female) who were still held there at the time of their release earlier this year. Researchers interviewed the two former detainees, Kostyantyn Beskorovaynyi and Artem (real name withheld), separately, and their stories are detailed below.[43] They separately shared their lists with Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch. The names on the two lists of 16 people are identical.

Beskorovaynyi and Artem also provided some basic details regarding the circumstances of detention for the individuals on their lists. Another individual, who was held in the same facility at the same time as Beskorovaynyi and Artem, but who asked for his case not to be included in this report, provided the same list of inmates to Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch and shared additional details regarding the circumstances of detention for the individuals on the list.[44] The UN report On the Human Rights Situation in Ukraine 15 February to 16 May 2016 described a similar situation based on the research findings by members of OHCHR, stating that “as of March 2016, OHCHR was aware of the names of 15 men and one woman disappeared in Kharkiv SBU.”[45]

In early June 2016, Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch sent a letter of inquiry to the SBU with regard to allegations of the enforced disappearances of individuals, in particular by members of the SBU on SBU premises in Kharkiv, Kramatorsk, Izyum, and Mariupol. The letter included specific questions on the cases of Beskorovaynyi and Artem documented in this section of the report. In their official response, dated June 17, 2016, SBU authorities denied operating any detention facilities with the exception of the temporary detention center in Kyiv (in respect of which no allegations of unacknowledged detention have come to Amnesty International or Human Rights Watch’s attention). They also stated that the SBU had never detained or investigated Beskorovaynyi and had no information about his case. The response did not address the discrepancy between the initial public acknowledgement by an SBU spokesperson of the arrest of a man whose details uniquely match Beskorovaynyi’s and the subsequent denial. As regards Artem, the response states that he has been under investigation by the SBU and was on remand between February 7 and March 12, 2015, and released thereafter.[46]

A delegation from the UN Subcommittee for Prevention of Torture, which began an official visit in Ukraine in May 2016, cut the visit short because the authorities failed to grant them access to some of the detention sites they wanted to visit. This is only the second time since it began its work in 2007 that the Subcommittee has chosen to cut short a country visit. The delegation chief, Malcolm Evans, stated that the team was prevented from visiting "some places where we have heard numerous and serious allegations that people have been detained and where torture or ill-treatment may have occurred."[47]

In response to the Subcommittee announcement, the head of the SBU, VasylyiHrytsak, told the press on May 26: "We are not holding any people in our territorial divisions....I'm convinced we have not violated anything."[48] The subcommittee has not disclosed the locations of the alleged places of detention to which it was denied access, but as the most recent OHCHR’s report specifically mentions Kharkiv SBU as an alleged place of unofficial detention,[49] this facility may have been on the Subcommittee’s list of sites to visit. [50]

The cases detailed below illustrate the unlawful practice of prolonged incommunicado detentions in unofficial prisons on the premises of SBU facilities.

Kostyantyn Beskorovaynyi (locations of detention: Kramatorsk, Izyum, Kharkiv)Kostyantyn Beskorovaynyi, 59 at time of writing, was an active member of the Communist Party of Ukraine (CPU) and an elected member of the local council in his hometown of Kostyantynivka, where he also worked as a dentist. Kostyantynivka had been under separatist control for several weeks in 2014 until it was retaken by the Ukrainian forces in July 2014.

Beskorovaynyi was the victim of an enforced disappearance, spending 15 months in unacknowledged and unlawful SBU detention in Kramatorsk, Izyum, and Kharkiv, most of it in the Kharkiv SBU building.[51]

Abduction and transfer to Kramatorsk SBU compoundAccording to Beskorovaynyi, at about 4 p.m. on November 27, 2014, masked men broke into his apartment, violently seized him, and searched his home with no warrant, claiming they had evidence that he planned to poison the local water supply:

Five or six masked men, one of them armed with an AK-47 automatic rifle, broke my door with a sledgehammer and threw me to the ground. They didn’t introduce themselves but accused me of being a terrorist and a separatist. One of them held me down with his foot and occasionally kicked me in the ribcage while the others searched my apartment….[52]

The search completed, they forced Beskorovaynyi into a van with no license plates and tinted windows. Inside, they handcuffed Beskorovaynyi and pulled a bag over his head. After a relatively short drive, they led Beskorovaynyi into a basement. There, his captors gave him a phone and forced him to call his wife and read a prepared statement stating that he had been detained for “speaking at a rally” and for “further clarifications.” In the evening, Beskorovaynyi was subjected to his first interrogation:

A group of four or five masked men questioned me. They were all aged 30-35, based on their voices, and all had local accents, except one. They told me that I was being charged with aiding a terrorist organisation but did not present any documents. Then, one of them punched me in the face and threatened to send “bearded fellows from Right Sector” to my wife and daughter … They struck me with something heavy, and threatened to rape and shoot me if I didn’t confess.[53]

Beskorovaynyi became so ill during the interrogation that his captors took him to a cell where two medical workers gave him an injection, which helped stabilize his condition. Then, he said, he was ready to confess to anything. His interrogators dictated a confession to him that he had allegedly planned to poison the local water supply and that he consented to work as an SBU informer. They then made him read it aloud on camera.

The next day, he overheard his wife talking with a guard outside, asking if he was there and begging to pass him some food and clothes. The guard claimed that Beskorovaynyi was “not there.” Later his relatives told him, and confirmed to our researchers, that the facility was in fact the SBU building in Kramatorsk, some 35 kilometers from Kostyantynivka.[54]

Transfer to Izyum and KharkivSeveral days later on December 3, several armed men in masks drove Beskorovaynyi to a different building, where he spent the night in the basement. The next morning, armed personnel again put him in a vehicle that already held two other detainees, and put a bag over his head.[55] As they drove away, Beskorovaynyi managed to make out a sign for the Izyum bus station, leading him to believe he had spent the night at the Izyum SBU building.

After what seemed like a couple of hours, the vehicle stopped in a city. The guards took Beskorovaynyi and the two other captives into a building and to a cell where he learned from one of the inmates that he was in the Kharkiv SBU building. The inmate told Beskorovaynyi he recognized the building because he had done an internship in it.

Almost 15 months in Kharkiv SBUBeskorovaynyi was held in Kkarkiv for nearly 15 months. Until his release in February 2016, the SBU held Beskorovaynyi on the second floor of the facility, moving him to a different cell five times. The total number of inmates in the facility ranged from around 70 when he first arrived to 17, including himself, at the time of his release.[56] Inmates were held in eight cells, the first four of which held up to around 15 detainees, while the other four were used for smaller groups of up to three people.[57] Between December 2014 and May 2015 Beskorovaynyi never left his cell for fresh air or exercise. From May 2015 onwards guards began to allow inmates a brief a walk in a small fenced yard twice a month.

Because the facility is small, inmates from different cells had ample opportunity to get to know one another, including during walks and doing kitchen duty. Beskorovaynyi and Artem met while detained in the SBU premises in Kharkiv.[58]

When Beskorovaynyi arrived at the facility, it was full. The inmates had to cook meals for around 70 people. The guards would grumble that they were paying for prisoners’ food “out of their own pockets.” The guards frequently told Beskorovaynyi and other inmates that “you don’t exist” and “we don’t even have a budget for you.”[59]

At least twice during his 15 months in custody—in February and October 2015—unidentified SBU officials said he would be exchanged soon, though this never happened.

In the first half of February 2015, the guards rounded up all the inmates, told them to gather their belongings and put the bags over their heads. Then the guards led them several floors upstairs and told them to keep quiet. When they returned to their cells several hours later, the detainees found that their cells had been cleaned and appeared uninhabited. Beskorovaynyi maintains that he overheard the guards talking about representatives of an international organization having visited the facility on that day.[60]

ReleaseSeveral days before his release in February 2016, Beskorovaynyi was instructed by a short, bespectacled investigator who introduced himself as Andrei to remain discreet about his time at the SBU:

‘Andrei’ told me that I had to tell everyone that I had left Kostyantynivka and gone into hiding for 15 months for personal reasons. He threatened to come for me and my family, even to send the Right Sector to get us in case I talk about what really happened.[61]

On February 24, 2016, Andrei told Beskorovaynyi that, although prisoner exchanges had stopped, the authorities were ready to let him go on the condition that he repeated his “confession” on camera. Beskorovaynyi did as he was told. He was again warned not to talk about his captivity. The following day he was given 200 UAH (just over US$7) for transport, driven to a bus station in Kharkiv, and made to buy a ticket home.[62]

Official denial of Kostyantyn Beskorovaynyi’s detentionDuring Beskorovaynyi’s detention, his family members repeatedly approached various Ukrainian authorities for information about his fate and whereabouts. They were consistently told that the authorities were not holding Kostyantyn Beskorovaynyi, although on at least one instance the SBU indirectly acknowledged his detention. The denial of Beskorovaynyi’s detention, and the repeated refusal to provide information on his whereabouts and fate, renders his arbitrary detention an enforced disappearance.

On December 19, 2014, Markiyan Lubkivskiy, the then-SBU spokesperson, said at a press briefing that counter-intelligence services and the SBU had detained an “insane Communist council member” from Kostyantynivka who had planned “terrorist attacks.”[63] There is little doubt Lubkivskiy was referring to Beskorovaynyi even though he did not name him; according to the records of Kostyantynivka town council, which were examined as part of this research, he was the only male Communist Party member on the town council at that time.

Nonetheless, the authorities officially denied to Beskorovaynyi’s family on repeated occasions that they were holding him. On the day of Beskorovaynyi’s detention, his wife filed a complaint with the local police authorities about his abduction by a group of unknown men. She also filed inquiries with several other government agencies. The reply she received from the SBU in Kharkiv, dated December 28, 2015, stated that in 2014-2015 Beskorovaynyi was not in official custody, nor under any investigation, nor a suspect in any criminal case.[64]

In June 2016 Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch received similar information in reply to their joint letter of inquiry, which stated that, as of June 17, 2016, the central SBU directorate had no information about Beskorovaynyi’s detention or any criminal allegations against him.[65]

Two criminal investigations were opened following Beskorovaynyi’s wife’s complaints: one into illegal deprivation of liberty and the other into abuse of official authority by law enforcement agencies. On April 13, 2016, the prosecutor's office in Kostyantynivkainformed Beskorovaynyi’s wife that the two investigations had been merged into one and transferred to the Military Prosecutor's Office for the Donetsk region.[66] She is not aware of any subsequent progress in the case.

Beskorovaynyi received several warnings to keep silent about his ordeal. On March 4, two men who introduced themselves as investigators from the local police precinct visited him at home. They insisted on questioning him and taking photos. He let them photograph him and said he would come to the police station the next day to provide an official statement. On March 5, at the police precinct, he told his full story to three law enforcement officials. They warned him that trying to sue the Ukrainian authorities could get him in trouble and tried to convince him to sign and backdate to the first day of his detention a letter of resignation from his job at the local hospital. Beskorovaynyi refused to sign it and believes that the officials wanted the ongoing investigations closed and planned to use the letter as evidence that he went missing of his own free will.[67]

At time of writing, Beskorovaynyi is trying to get reinstated in his job and to have his allegations officially investigated.

Artem (real name withheld; locations of detention: Mariupol, Kharkiv)Artem, a pro-separatist activist in Mariupol, was forcibly disappeared while walking along a street by masked armed men on January 28, 2015. Artem spent the next 11 days detained in a basement, where he says he was subjected to torture and other ill-treatment. He was then handed over to the SBU. At this point, his detention was formally recognized and he was officially charged with aiding a terrorist organization.[68] After 31 days in pre-trial detention, a judge ordered his release from custody under his own recognizance. Notably, the request to release him came from the SBU. However, instead of releasing him, SBU officials transferred Artem to the Kharkiv SBU compound, where he was held incommunicado for another 11 months before being exchanged as part of a “prisoner swap” in February 2016.[69]

Detention and tortureArtem said his captors stopped him on 50-richnaya Oktyabrya street in Mariupol, pulled a plastic bag over his head, threw him into the back of a car, and brought him to the basement of a building. Months later, when Artem described this building to fellow detainees in Kharkiv, some of them said they had also been held and tortured there and identified it as the sports school near Soyuz cinema, which was used as a base by the volunteer battalion Azov.

According to Artem, his captors handcuffed him for long periods of time to a metal rod hanging from the ceiling in the basement and hit him repeatedly on his head and stomach, demanding that he tell them “everything.” The beating sessions continued for two days with short intervals in between. Artem’s torturers also instructed the guards to keep him from sleeping at night.

Artem provided a detailed description of some of the worst moments of his ordeal:

On the third day … they brought two stripped electric wires and ran electricity on my stomach. I was convulsing so heavily that they had to chain me to a wooden ladder, but it broke from my convulsions. Then they turned me over and applied the wires to my back. After I lost consciousness several times, they pulled down my pants and applied the wires to my genitals.... They wanted to know something about a handgun but I told them that I’d never held a weapon in my entire life. They threatened to cut my thumb and then placed a wet mop on my face and started pouring water on it. I felt like I was drowning. There was this official in charge, everyone called him Polkovnik [“colonel” in Russian]. [He] wanted to know about my family and when I said my son was just six years of age, he shouted to the others, “Bring him here, I’ll tear the kid apart in front of him!” After this I told them I’ll confess to anything, do anything they want.[70]

Transfer to Mariupol SBU and to remand prisonOn February 7, the guards moved Artem from the basement to a makeshift cell in the same building, where he was allowed to take the bag off his head for the first time. Several hours later, two officers who said they were from the SBU told Artem that they had been looking for him for six days and instructed the guards not to touch him. They took Artem to the SBU building in Mariupol, where he spent two days in incommunicado detention. On February 9, SBU officials informed Artem that the Zhovtnevyi court in Mariupol had ordered his pre-trial detention for 60 days on charges of “aiding a terrorist organization.” On the same day, Artem was transferred to a pre-trial detention center in Kamensk. Upon arrival, Artem was examined by medical personnel, as the law requires, who noticed multiple bruises and abrasions on his body. A law enforcement official present during the examination told Artem: “It’s impossible to find the people who did this to you because of the [chaotic] situation in town, and it’s in your best interests to have them recorded as injuries during your arrest.” Artem agreed to do as he was told.[71]

Transfer to Kharkiv SBU compoundOn March 12, Artem was brought before a judge who considered and approved a request submitted by an SBU investigator to lift Artem’s remand.[72] However, on March 13, instead of being released, Artem was again forcibly disappeared, together with nine other inmates, and held at the SBU compound in Kharkiv. He was not presented with any official paperwork, nor given any explanation.

Artem spent the next 11 months forcibly disappeared—in unacknowledged detention—on the premises of the SBU compound in Kharkiv and was finally exchanged for detainees held by the separatist forces on February 20, 2016.

He described his cell at the SBU compound in Kharkiv:

The cell was about eight by eight meters with bars on the windows and a plastic sheet behind the bars so we could not see anything on the street. There were 11 other people in the cell when I arrived. I stayed there until 20 February 2016. They fed us three times per day, two spoons of oats and a tiny slice of bread with tea. On Saturdays and Sundays for breakfast we had only tea.... At the end of August 2015, the canteen refused to cook for us, so we started doing it on our own... They allowed doctors in only when something was very urgent. But once, when a person had a stroke and half of his body was paralyzed, they did not call a doctor. A person with diabetes was given insulin only once every two weeks. If there were some altercations between us, the guards used pepper-spray in the cells. They did not allow us to contact our relatives or anyone else.[73]

Artem claims he met Kostyantyn Beskorovaynyi at the SBU compound in Kharkiv and gave a similar description of the conditions there.[74]

Once in the DNR-controlled territory, Artem underwent a forensic medical examination. His medical records documented visible scars from deep wounds on his wrists, consistent with his claims of being suspended by handcuffs for a long period of time, and a broken tooth.[75] These scars were visible during his interview with Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch researchers.

Artem has not filed any complaints with the Ukrainian authorities regarding his enforced disappearance and ill-treatment due to fear of reprisals against his wife and child, who are still in Mariupol. For the same reason, he is afraid to contact his wife and does not know if she has contacted any official agencies about his fate and whereabouts.

The official response received by Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch from the SBU and dated June 17, 2016, stated he has been under investigation by the SBU and was on remand between February 7 and March 12, 2015 and released thereafter.[76]