ANOTHER STORM

IN THE LATTER PART of 1951, a new storm broke around one of my paintings. In order for it to be understood at all, I have to sketch the prevailing political and personal landscape.

At the beginning of the administration of President Aleman, the composer Carlos Chavez, Director of the Fine Arts Institute, made plans for an exhibition of Mexican art in Europe. Chavez had the typical Mexican sense of inferiority in matters artistic, and corresponding awe toward the culture of the Old World. His hope was to impress the Old World with what the New World could produce and thus establish an international reputation for himself as well.

Chavez's associate in this undertaking was Fernando Gamboa of the Plastic Arts Department. Gamboa expected to gain recognition for himself as a promoter of the Mexican plastic movement in international art. He also had a more immediate purpose from which he hoped to gain -- to publicize the good name of Aleman.

Aleman was at this time ambitious to receive the Nobel Peace Prize. He also fostered hopes of ultimately succeeding Trygve Lie as Secretary General of the United Nations.

The instigator of these dreams was the Swedish millionaire Axel Wenner-Gren. Through a stock transfer during World War II, Wenner-Gren had turned over control of Swedish steel production to the Nazis. His claim was that he had done this to save his country from invasion. The brothers Maximino and Manuel Avila Camacho, the latter President of Mexico, had, however, overlooked this questionable episode in the millionaire's career because of his willingness to invest in Mexican industries, and welcomed him to Mexico. When Aleman took over the Presidency from Avila Camacho, he also inherited the friendship of Wenner-Gren, who promised to promote Aleman at the Swedish Academy and in the United Nations, in both of which he claimed to have influence.

The exhibition of Mexican art planned by Chavez to be held in Stockholm would provide a marvelous backdrop for the scene of Aleman receiving the Peace Prize. And, of course, Chavez and his assistant, Gamboa, would bask in the reflected glory. They could see themselves receiving titles and decorations, not to mention money. But there was one feature of the plan which they and Aleman overlooked -- Wenner-Gren was disliked by most of the decent people in Sweden.

Also, unfortunately for them, at the moment when votes were taken for the Peace Prize, dozens of people were killed in the streets of Mexico by machine guns manned by the mounted police comprising Aleman's personal military guard. The sound of the chattering weapons and the cries of the innocents could be heard even above Aleman's call for peace in Korea. No wonder he was balloted out of the running, despite the fact that his was the only name which had been officially submitted.

Chavez's plan for the art exhibition, however, did not die with Aleman's personal hopes. Its locus was shifted to Paris. And when the time came, Senor Gamboa and his tall, lovely American wife were dispatched there with vast treasures of Mexican art to court the approval of Mother Europe.

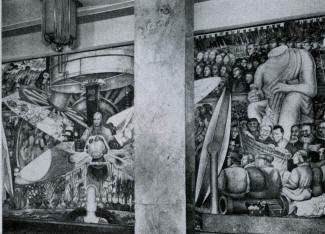

As to my involvement in all this: I was requested to paint a movable mural which, after being shown in the exhibition, was to be mounted in Mexico City's Palace of Fine Arts alongside my second "Rockefeller" mural.

When I received this commission from the Fine Arts Institute, I was told that I had complete freedom of choice in style and subject matter. Pleased by this expression of confidence, I planned to show my gratitude by authorizing the work to be displayed not only in Paris but wherever else it might be welcome. I began to organize a collection of some of my other paintings with this in mind.

However, I soon came to suspect that all was not as it should be. The commission allowed me only thirty-five days to work on the mural before it was sent out. Had anyone hoped to give me insufficient time to complete it, he need not have waited much longer. Examining my contract, I found none of the standard clauses regarding the failure of either party to carry out its commitments.

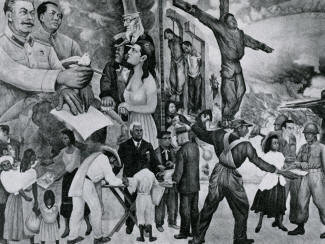

Nevertheless, I went ahead with my part of the bargain. My subject matter would complement and carry forward that of the Rockefeller mural. In the latter, I had portrayed my premonitions concerning the second World War, most uncannily as it turned out, in an actual battlefield scene and in a prophecy of atomic fission. In the new fresco, against a background of hangings, burnings, shootings, and an atomic explosion, I meant to show the movement for peace which could end the threat of a third World War.

On the very first of the thirty-five days, Chavez came to see me to set the exact dimension of my mural. As I outlined my theme, Chavez expressed his pleasure at being able to show an example of my type of painting together with such contrasting types as Tamayo's abstractions and Siqueiros' historical allegories.

In the foreground of my mural, I explained to Chavez, I would portray those friends of mine who had been most active in collecting signatures for the peace petition. In addition, I said, I would include monumental portraits of Stalin and Mao Tse-tung proffering pen and peace treaty to John Bull, Uncle Sam, and Belle Marianne. I explained that in these representations of the Russian and Chinese leaders, I hoped to create symbolic figures to correspond with those of Great Britain, the United States, and France.

Chavez was all honey and congratulations on this initial visit. But after I had worked steadily on my mural night and day for several days, I sensed a growing coolness on Chavez's part. He began to express doubt about how the painting would be received in Europe.

It was not, however, until the mural was nearly finished that Chavez interposed the question of whether the French government itself might not take offense and cancel the entire exhibition. For that reason, Chavez explained, it was necessary for him to confer with the Minister of Education.

Chavez reported the minister's decision to me. My work would not be sent to Paris but exhibited only in the Palace of Fine Arts. I insisted upon the fulfillment of my contract, particularly the clauses guaranteeing me freedom of expression.

Chavez did not answer my protest; instead he initiated a debate in the press concerning the "unwise" point of view represented in my mural. As a result, the Minister of Education adjudged my painting not only unsuitable to be shown abroad but also unacceptable for display in the Fine Arts Palace, on the ground that my subject matter would probably offend some of the big countries with which Mexico maintained amicable relations.

I sent out an inquiry to determine whether the ambassadors of these presumably sensitive nations -- Great Britain, the United States, and France -- had voiced any protest thus far, but received no satisfactory reply. This left me with no recourse but to secure the individual reactions of these personages personally. The French Ambassador told me his wife had seen the mural and found nothing objectionable in it; as representative of his government, he was certain that it would take the same view. I called upon the British Ambassador and, through the first secretary of the British embassy, who had seen my painting several times, I was given a similar favorable reply.

This left only William O'Dwyer, the American Ambassador, to be heard from. It happened that at this time I was invited to a tea party given by the wife of President Aleman. Among the guests were the American Ambassador and his wife, Sloan Simpson, as well as my old friend Carlos Chavez.

In time the conversation lighted on my mural. Mrs. O'Dwyer rhetorically asked whether my depiction of an atomic explosion in the background wasn't too realistic and whether I had represented American soldiers in it with sufficient sympathy. She felt my painting judged her country too harshly.

When the party was over, Chavez, who had heretofore treated me more like a brother than a friend, relayed Mrs. O'Dwyer's doubts to the Minister of Education, who in turn went to see Aleman, already prejudiced against my mural by his wife. Aleman, however, tossed the matter back into the laps of the Minister of Education and Chavez, who now began playing an absurd game, using me as the ball.

Chavez came to tell me that my mural might easily ruin the entire exhibition. However, he would insist that it be shown in the Fine Arts Palace or hand in his resignation.

The bitterness of my retort offended Chavez grievously, He reopened the controversy in the newspapers, hoping, I am sure, that the harassment would keep me from finishing my mural on schedule. But I worked harder than ever and was actually done even before the deadline. I then immediately held a public showing of the work, so that if anything wrong were seen in it, I could revise.

Never before had a painting of mine been so enthusiastically received by the Mexican people, and particularly by the workers and peasants. Despite the fact that there was little publicity, a crowd of more than three thousand came to look at the mural between 7:00 P.M. and midnight of that first evening. Many diplomats from Latin American countries were among the visitors.

During the showing I had the honor to receive the ambassador of the Soviet Union and the ministers of Poland and Czechoslovakia. They all congratulated me warmly, as did the President of the Mexican Peace Committee and numerous other intellectuals and politicians. Neither Chavez nor any other official of either the Fine Arts Institute or the Ministry of Public Education put in an appearance.

However, when the show was over, some friends of mine overheard Chavez and several of his cronies plotting in a restaurant to dismantle my painting and to ask Aleman for assistance in their scheme. These friends relayed the information to partisans of mine who were guarding the painting in the Fine Arts Palace. The following day thirty troopers of Aleman's personal security force moved into the room adjoining the one where my painting was on display.

Frida and some of my friends, sensing trouble, urged me to leave the palace. I was terribly tired, for I had been painting for three days and nights without stopping to sleep or rest. My dear friend Dr. Ignacio Millan told me that if I didn't let up I would certainly have a nervous breakdown. Yet I was reluctant to leave; I knew that as long as I remained at my post, it would be difficult to carry out any action against my mural.

But Frida, who had left the hospital in a wheelchair, finally persuaded me to come away with her. She feared that violence would be used and, with the odds against me, that my life was in jeopardy. I could offer no counterarguments. Many ruthless and inhuman crimes had been effected by the people who were now ranged against me. The murders they had committed were explained away either as gangster attacks or as fatalities resulting from the victims resisting the police.

So I went home and to bed. In the following week, I was so sick and depressed that everyone thought I would die. But thanks to Frida, I rallied and little by little regained my will to live.

When Chavez learned that I had left the Palace, he hastened to it and ordered the police commander to have his men cut the painting down from its stretcher. Upon the latter's refusal to commit such a felony, even at the risk of losing his job, Chavez, the famous composer and official conservator of Mexican art, heroic Chavez, with the Stalingrad Symphony or possibly the Eroica ringing in his ears, himself took knife in hand and attacked my painting. Not wanting to appear less courageous than Chavez, one of my helpers, in hopes of delaying the vandalism as long as possible, cried out that while Senor Chavez might be very expert in directing an orchestra, he wasn't the best man to dismantle a painting. This only encouraged Chavez's lieutenant, Fernando Gamboa, to offer his own talented hands in aid of his superior, the genius composer. As soon as the painting had been cut down, Chavez gave the order to roll it up. This done, he commanded that none of the people working in the Palace of Fine Arts follow him. He personally escorted the rolled-up canvas, borne by a pair of troopers, out of the building. Only Gamboa, his equal in courage, was permitted to go along. The canvas was taken to the basement, where it was stored in a secret place. The business was carried out as if it were of the most tremendous import -- as if my painting of an atomic explosion were the atom bomb itself.

The next day, before sunrise, Gamboa left Mexico City incognito, heading in the direction of an archeological center of pre-Hispanic ruins. Chavez, too, left the scene of his doughty deed and, certain he would receive unending favors from his master Aleman, hurried to his home in Acapulco.

Anticipating an inquiry, Maestro Chavez had already concocted a story for the press, which must rank among the worst Hollywood movies and the trashiest crime novels. According to this tale, fifteen masked men had invaded the palace late at night, cowed the night watchman into silence with machine guns, and then cut down my painting and run off with it.

Poor Miss Llach, Chavez's secretary and chief of the administrative department of the Institute, brought this "news" to me in my house in Coyoacan together with a check for 30,000 pesos, which represented the balance due me of the stipulated fee of 50,000 pesos. Naturally I refused to accept the check. I also refused to permit her to leave the house before my lawyer, Alejandro Gomez Arias, could come to make an official record of the "facts" as she had stated them. Arias, a distinguished orator and man of letters, took down Miss Llach's recitation. At the end of it, he declared that in his opinion, not only had my rights under the contract and my artistic rights in general been violated, but that I could claim damages for the theft of my painting as soon as the criminals were found.

Furthermore, Arias declared, the case would have to be put in the hands of the Attorney General, since the Institute was no longer responsible, the robbers evidently having had no connection with its authorities. Whereupon Miss Llach declared that she herself felt a bit dubious about Chavez's version of the crime. She personally refused to assume any responsibility in connection with it.

Arias then summoned a notary public to make these last statements of hers official, and then presented the case to the Attorney General. This gentleman immediately assigned two of his agents to study the matter further. He advised Miss Llach not to leave her office in the Fine Arts Palace until after the investigation had been completed.

Two hours later I was summoned to the Attorney General's office. Some policeman and a notary public were in attendance.

Meanwhile, Miss Llach may have succeeded in communicating with Chavez and he, his feet chilling, had advised her to tell the truth. Perhaps, good woman that she really was, she had decided that she had had enough of dissimulation.

In any case, in the presence of a representative of the Attorney General, the policemen, and me, Miss Llach retracted her original story -- Chavez's story. Instead she told the truth, that the painting had been cut down from its stretcher, rolled up, and hidden somewhere in the palace. She said that the act had been performed on orders received from the highest authorities of the Institute. Who precisely had issued these orders? The Minister of Education? Miss Llach answered in the negative. Senor Chavez? The answer was again "No." There was only one highest authority left, the President of the Republic. But at this point, Miss Llach broke down and, in tears, declared that she had been commanded by Chavez not to name names under any circumstances. To this extent the matter was clarified and the entire shameful responsibility for the act placed with the Institute of Fine Arts.

After leaving the Attorney General's office late in the afternoon, I arranged a meeting with other painters who had been greatly agitated by my experience. It was decided that we convene a press conference the following morning at eleven o'clock in the home of Siqueiros' sister-in-law. Representatives of all the daily papers and reviews, and many foreign correspondents, came and were given the whole story. They sent out their dispatches right from the house, and their accounts made headlines in the afternoon papers. Excelsior even brought out an extra edition.

Two hours after the conference, Chavez, back by plane from Acapulco, telephoned my lawyer to ask for a gentlemen's agreement with me. I was to withdraw my accusations and give back my advance and, in return, receive my mural, stretchers, and all other materials mentioned in my contract.

The agreement was accepted. At exactly five o'clock that same day, Chavez, having "found" my purloined painting, accompanied me to the door of the Fine Arts Palace. He shook my hand, declaring the incident closed, and asked for a renewal of our friendship.

"I declare the incident closed," I responded, "and also, I declare as ended your status as a decent human being, Further, I declare as being completely terminated our former friendship. Good-bye."

On the opening day of the Mexican art exhibition in Paris, 2,500,000 copies of Humanite, journal of the French workers, put reproductions of my banned mural into as many hands and told the whole story concerning it. Reproductions were also sold at the door of the exhibition by young men and women belonging to progressive peace organizations. Many more such reproductions were sold all over the world, especially in the United States and China. The government of China finally acquired the original work.

In short, my painting turned out to be more successful for having been withdrawn than it would have been if quietly shown to the art-going public in Paris. Chavez, Gamboa, and company succeeded in making themselves notorious before the entire world as futile suppressors of the right of freedom of expression -- a most ignoble and unenviable distinction.

Diego Rivera: My Art, My Life. An Autobiography With Gladys

Re: Diego Rivera: My Art, My Life. An Autobiography With Gla

CANCER

IN 1952 I began to be bothered by pain in the penis, the swelling of that organ, and the retention of urine. After making the usual tests, my physician diagnosed my illness as cancer of the penis. He advised amputating my penis and testicles to prevent the spread of the malignancy.

I objected to this horrifying proposal and asked the doctor to try to arrest the cancer with X-ray therapy instead. "If you cannot," I said, "I want everything to remain as it is. I will be completely responsible. I refuse to allow the amputation of those organs which have given me the finest pleasure I know."

My doctor acceded to the request, and I underwent X-ray treatments. After a few months my symptoms disappeared. The doctor then performed a biopsy, which showed the malignancy to have been arrested. Reports of my rapid and amazing recovery were made known to medical groups all over the world. Cancer of the penis is so rare in this hemisphere as to evoke much curiosity. One of the foremost radiologists of the United States flew to Mexico just to study my case.

After this frightening experience, I altered my diet in order to keep my body in the best of condition. Bearing in mind my doctor's maxim that, for every two pounds of weight I lost, I would live another year, I cut down on fats and starches and proportionally increased my intake of proteins. For the next few years my lunch, my main meal, consisted of two eggs, meat, two slices of black bread, yogurt, a cooked dessert, six different fruits, and a tall thermos of unsweetened black coffee. This was packed for me at home in a laborer's lunchbox which I carried with me onto the scaffold, eating when one of my helpers reminded me it was mealtime.

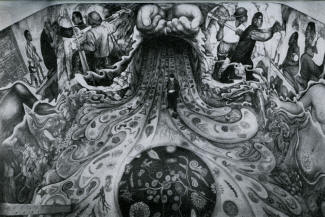

While I was undergoing treatment, I passed through a deep personal depression, dominated by the feeling that my life was practically over. It happened that during this time I was working on a wall of the new Hospital de la Raza. My subject was the history of medicine in Mexico. On the left side of the mural, I painted a giant, phallic, yellow-green Tree of Life. Suddenly I was stopped by a painful idea flashing through my mind. Gazing wistfully at my creation, I thought, "No more for me. Physical love exists for me no longer. I am an old man, too old and too sick to enjoy that wonderful ecstasy."

As my health returned I became restless. I yearned to go back to Europe and paint there again. It seemed to me that despite all the work I had been doing in the past few years, I had been asleep and not even dreaming. In 1946 I had passed up a second invitation to paint in Italy, extended by the administration of Alcide de Gasperi.

Now I decided to take advantage of the opportunity provided by the Vienna World Peace Conference to travel on the continent which had been my second home. Accompanied by my younger daughter Ruth, I left Mexico for Austria in January of 1953, planning to stop on the way back in Chile, where another peace conference was scheduled some weeks later.

Vienna, it seemed to me, had not yet shaken off the effects of the recent war. The despair of the people, which I observed during the conference, was reflected in the incomplete restoration of the city. Vienna was like a gravely wounded man who has experienced everything, and in the recesses of his heart, yearns only for order and peace.

When the conference was over I made a short junket to Czechoslovakia. Here, by contrast, I observed a remarkable recovery from the war. It was as if I were in another world. I was surprised and delighted. The people were happy and busy, and their activity showed a deep and positive sense of purpose. As I wandered through the towns and cities, I came upon murals noteworthy not only for their technical maturity but for the enjoyment and enthusiasm for life they expressed. Even the industrial murals had a deeply poetic quality.

When I got back to Mexico, I felt renewed again. The trip had admirably served its purpose as a tonic. Sometime in the future I would like to commemorate it in a painting of the Vienna World Peace Conference from sketches which I made at the time -- a mural if possible, but if not, a large canvas, depicting the final session as I remember it.

IN 1952 I began to be bothered by pain in the penis, the swelling of that organ, and the retention of urine. After making the usual tests, my physician diagnosed my illness as cancer of the penis. He advised amputating my penis and testicles to prevent the spread of the malignancy.

I objected to this horrifying proposal and asked the doctor to try to arrest the cancer with X-ray therapy instead. "If you cannot," I said, "I want everything to remain as it is. I will be completely responsible. I refuse to allow the amputation of those organs which have given me the finest pleasure I know."

My doctor acceded to the request, and I underwent X-ray treatments. After a few months my symptoms disappeared. The doctor then performed a biopsy, which showed the malignancy to have been arrested. Reports of my rapid and amazing recovery were made known to medical groups all over the world. Cancer of the penis is so rare in this hemisphere as to evoke much curiosity. One of the foremost radiologists of the United States flew to Mexico just to study my case.

After this frightening experience, I altered my diet in order to keep my body in the best of condition. Bearing in mind my doctor's maxim that, for every two pounds of weight I lost, I would live another year, I cut down on fats and starches and proportionally increased my intake of proteins. For the next few years my lunch, my main meal, consisted of two eggs, meat, two slices of black bread, yogurt, a cooked dessert, six different fruits, and a tall thermos of unsweetened black coffee. This was packed for me at home in a laborer's lunchbox which I carried with me onto the scaffold, eating when one of my helpers reminded me it was mealtime.

While I was undergoing treatment, I passed through a deep personal depression, dominated by the feeling that my life was practically over. It happened that during this time I was working on a wall of the new Hospital de la Raza. My subject was the history of medicine in Mexico. On the left side of the mural, I painted a giant, phallic, yellow-green Tree of Life. Suddenly I was stopped by a painful idea flashing through my mind. Gazing wistfully at my creation, I thought, "No more for me. Physical love exists for me no longer. I am an old man, too old and too sick to enjoy that wonderful ecstasy."

As my health returned I became restless. I yearned to go back to Europe and paint there again. It seemed to me that despite all the work I had been doing in the past few years, I had been asleep and not even dreaming. In 1946 I had passed up a second invitation to paint in Italy, extended by the administration of Alcide de Gasperi.

Now I decided to take advantage of the opportunity provided by the Vienna World Peace Conference to travel on the continent which had been my second home. Accompanied by my younger daughter Ruth, I left Mexico for Austria in January of 1953, planning to stop on the way back in Chile, where another peace conference was scheduled some weeks later.

Vienna, it seemed to me, had not yet shaken off the effects of the recent war. The despair of the people, which I observed during the conference, was reflected in the incomplete restoration of the city. Vienna was like a gravely wounded man who has experienced everything, and in the recesses of his heart, yearns only for order and peace.

When the conference was over I made a short junket to Czechoslovakia. Here, by contrast, I observed a remarkable recovery from the war. It was as if I were in another world. I was surprised and delighted. The people were happy and busy, and their activity showed a deep and positive sense of purpose. As I wandered through the towns and cities, I came upon murals noteworthy not only for their technical maturity but for the enjoyment and enthusiasm for life they expressed. Even the industrial murals had a deeply poetic quality.

When I got back to Mexico, I felt renewed again. The trip had admirably served its purpose as a tonic. Sometime in the future I would like to commemorate it in a painting of the Vienna World Peace Conference from sketches which I made at the time -- a mural if possible, but if not, a large canvas, depicting the final session as I remember it.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 36183

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Diego Rivera: My Art, My Life. An Autobiography With Gla

YET ANOTHER STORM

TOWARD THE END of February, 1953, I was commissioned to do a mural on an outside wall of the new Teatro de los Insurgentes. Designed by the brothers Julio and Alejandro Prieto, this motion-picture house belonged to the master politician and composer of songs Jose Maria Davila and his vivacious and attractive wife, Queta. It was Senora Davila, chiefly, who was responsible for my being offered this interesting commission.

The space I was given comprised the whole main facade of the theatre, facing the busy Avenida de los Insurgentes. The plastic problem here was extremely challenging. For the surface was curved at the top and convex, and most of the people who would see the mural would be passing it quickly in cars and buses.

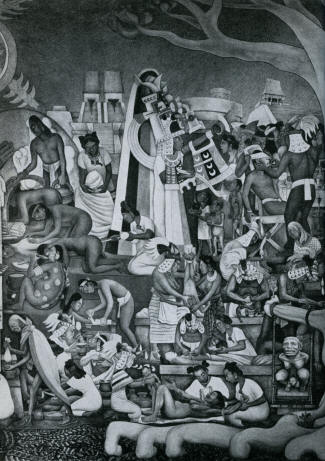

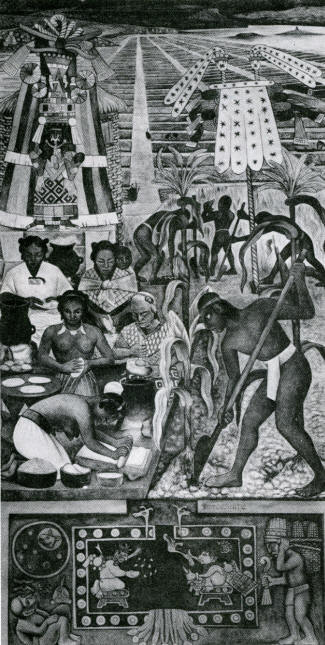

To establish immediately the theme of the mural and the purpose of the building, I painted a large masked head with two female hands in delicately laced evening gloves in the lower central portion. I covered the remaining surface with scenes from plays reflecting the history of Mexico from pre-Colonial times to the present, and converging in the upper center in a portrait of Cantinflas, the Mexican genius of popular farce, asking for money from the rich people and giving it to the poor, as he actually does.

It was this scene which precipitated the storm, When only the first charcoal sketch had been done, someone noticed that Cantinflas was wearing a medal of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Immediately there arose a hue and cry. It was blasphemous to connect a low comedy figure with something as sacred as the Virgin.

Interviewed by reporters, Cantinflas said that if I had actually blasphemed against the Virgin of Guadalupe in my mural, he would never permit any of his films to be shown in the theater. But my representation could be simply literal, for he always wore the medal in real life. Nobody, Cantinflas said, could either take it away from him or mock his reverence and love.

When Cantinflas saw my sketch, he was perfectly satisfied. He even posed with me for pictures on the scaffold beside the place where I had drawn the Virgin. He stood next to me, proudly showing his medal for the public to see in the photographers' prints.

Having Cantinflas' endorsement, the press came over to my side, pointing out that there was nothing contradictory between Cantinflas and the Virgin of Guadalupe. Cantinflas was an artist who symbolized the people of Mexico, and the Virgin was the banner of their faith.

A majority of the public subscribed to this interpretation. But the agitation against my painting was not allowed to die away. In fact, it was organized by a gangster syndicate led by professional extortioners, posing as staunch supporters of the Faith.

The gangsters' purpose was to shake down the Davilas for a percentage of the profits of the theater -- their price for tranquility. Not only the Davilas, but even Cantinflas began to be frightened by the situation, and finally, I myself ceased to find it amusing. So when I got to that portion of the mural where the Virgin had been sketched, I did not paint her in at all, outwitting both friends and enemies, false and true. Executing this unexpected turnabout, I must admit, gave me not a little pleasure.

TOWARD THE END of February, 1953, I was commissioned to do a mural on an outside wall of the new Teatro de los Insurgentes. Designed by the brothers Julio and Alejandro Prieto, this motion-picture house belonged to the master politician and composer of songs Jose Maria Davila and his vivacious and attractive wife, Queta. It was Senora Davila, chiefly, who was responsible for my being offered this interesting commission.

The space I was given comprised the whole main facade of the theatre, facing the busy Avenida de los Insurgentes. The plastic problem here was extremely challenging. For the surface was curved at the top and convex, and most of the people who would see the mural would be passing it quickly in cars and buses.

To establish immediately the theme of the mural and the purpose of the building, I painted a large masked head with two female hands in delicately laced evening gloves in the lower central portion. I covered the remaining surface with scenes from plays reflecting the history of Mexico from pre-Colonial times to the present, and converging in the upper center in a portrait of Cantinflas, the Mexican genius of popular farce, asking for money from the rich people and giving it to the poor, as he actually does.

It was this scene which precipitated the storm, When only the first charcoal sketch had been done, someone noticed that Cantinflas was wearing a medal of the Virgin of Guadalupe. Immediately there arose a hue and cry. It was blasphemous to connect a low comedy figure with something as sacred as the Virgin.

Interviewed by reporters, Cantinflas said that if I had actually blasphemed against the Virgin of Guadalupe in my mural, he would never permit any of his films to be shown in the theater. But my representation could be simply literal, for he always wore the medal in real life. Nobody, Cantinflas said, could either take it away from him or mock his reverence and love.

When Cantinflas saw my sketch, he was perfectly satisfied. He even posed with me for pictures on the scaffold beside the place where I had drawn the Virgin. He stood next to me, proudly showing his medal for the public to see in the photographers' prints.

Having Cantinflas' endorsement, the press came over to my side, pointing out that there was nothing contradictory between Cantinflas and the Virgin of Guadalupe. Cantinflas was an artist who symbolized the people of Mexico, and the Virgin was the banner of their faith.

A majority of the public subscribed to this interpretation. But the agitation against my painting was not allowed to die away. In fact, it was organized by a gangster syndicate led by professional extortioners, posing as staunch supporters of the Faith.

The gangsters' purpose was to shake down the Davilas for a percentage of the profits of the theater -- their price for tranquility. Not only the Davilas, but even Cantinflas began to be frightened by the situation, and finally, I myself ceased to find it amusing. So when I got to that portion of the mural where the Virgin had been sketched, I did not paint her in at all, outwitting both friends and enemies, false and true. Executing this unexpected turnabout, I must admit, gave me not a little pleasure.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 36183

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Diego Rivera: My Art, My Life. An Autobiography With Gla

FRIDA DIES

FOR ME, the most thrilling event of 1953 was Frida's one-man show in Mexico City during the month of April. Anyone who attended it could not but marvel at her great talent. Even I was impressed when I saw all her work together. The arrangements had been made by her many friends as their personal tribute to her.

At the time Frida was bedridden -- a few months later one of her legs was to be amputated -- and she arrived in an ambulance, like a heroine, in the midst of admirers and friends.

Frida sat in the room quietly and happily, pleased at the numbers of people who were honoring her so warmly. She said practically nothing, but I thought afterwards that she must have realized she was bidding good-bye to life.

The following August she re-entered the hospital to have her leg cut off at the knee. The nerves had died and gangrene had set in. The doctors had told her that if they didn't perform this operation, the poison would spread through her whole body and kill her. With typical courage, she asked them to amputate as soon as possible. The operation was her fourteenth in sixteen years.

Following the loss of her leg, Frida became deeply depressed. She no longer even wanted to hear me tell her of my love affairs, which she had enjoyed hearing about after our remarriage. She had lost her will to live.

Often, during her convalescence, her nurse would phone to me that Frida was crying and saying she wanted to die. I would immediately stop painting and rush home to comfort her. When Frida was resting peacefully again, I would return to my painting and work overtime to make up for the lost hours. Some days I was so tired that I would fall asleep in my chair, high up on the scaffold.

Eventually I set up a round-the-clock watch of nurses to tend to Frida's needs. The expense of this, coupled with other medical costs, exceeded what I was earning painting murals, so I supplemented my income by doing water colors, sometimes tossing off two big water colors a day.

In May, 1954, Frida seemed to be rallying. One raw night in June she insisted upon attending a demonstration and caught pneumonia. She was put back in bed for three weeks more. Almost recovered, she arose one night in July and against the doctor's orders, took a bath.

Three days later she began to feel violently ill. I sat beside her bed until 2:30 in the morning. At four o'clock she complained of severe discomfort. When the doctor arrived at daybreak, he found that she had died a short time before of an embolism of the lungs.

When I went into her room to look at her, her face was tranquil and seemed more beautiful than ever. The night before she had given me a ring she had bought me as a gift for our twenty-fifth anniversary, still seventeen days away. I had asked her why she was presenting it so early and she had replied, "Because I feel I am going to leave you very soon."

But though she knew she would die, she must have put up a struggle for life. Otherwise, why should death have been obliged to surprise her by stealing away her breath while she was asleep?

According to her wish, her coffin was draped with the Mexican Communist flag, and thus she lay in state in the Palace of Fine Arts. Reactionary government officials raised a cry against this display of a revolutionary symbol, and our good friend Dr. Andres Iduarte, Director of the Fine Arts Institute, was fired from his post for permitting it. The newspapers amplified the noise and it was heard throughout the world.

I was oblivious to it all. July 13, 1954, was the most tragic day of my life. I had lost my beloved Frida forever.

When I left, I turned over our house in Coyoacan to the government as a museum for those paintings of mine which Frida had owned. I made only one other stipulation: that a corner be set aside for me, alone, for whenever I felt the need to return to the atmosphere which recreated Frida's presence.

Once out of Coyoacan, I went on a mad tear of the nightclubs. I hate them, and yet I couldn't bear being alone with my thoughts. My only consolation now was my readmission into the Communist Party.

FOR ME, the most thrilling event of 1953 was Frida's one-man show in Mexico City during the month of April. Anyone who attended it could not but marvel at her great talent. Even I was impressed when I saw all her work together. The arrangements had been made by her many friends as their personal tribute to her.

At the time Frida was bedridden -- a few months later one of her legs was to be amputated -- and she arrived in an ambulance, like a heroine, in the midst of admirers and friends.

Frida sat in the room quietly and happily, pleased at the numbers of people who were honoring her so warmly. She said practically nothing, but I thought afterwards that she must have realized she was bidding good-bye to life.

The following August she re-entered the hospital to have her leg cut off at the knee. The nerves had died and gangrene had set in. The doctors had told her that if they didn't perform this operation, the poison would spread through her whole body and kill her. With typical courage, she asked them to amputate as soon as possible. The operation was her fourteenth in sixteen years.

Following the loss of her leg, Frida became deeply depressed. She no longer even wanted to hear me tell her of my love affairs, which she had enjoyed hearing about after our remarriage. She had lost her will to live.

Often, during her convalescence, her nurse would phone to me that Frida was crying and saying she wanted to die. I would immediately stop painting and rush home to comfort her. When Frida was resting peacefully again, I would return to my painting and work overtime to make up for the lost hours. Some days I was so tired that I would fall asleep in my chair, high up on the scaffold.

Eventually I set up a round-the-clock watch of nurses to tend to Frida's needs. The expense of this, coupled with other medical costs, exceeded what I was earning painting murals, so I supplemented my income by doing water colors, sometimes tossing off two big water colors a day.

In May, 1954, Frida seemed to be rallying. One raw night in June she insisted upon attending a demonstration and caught pneumonia. She was put back in bed for three weeks more. Almost recovered, she arose one night in July and against the doctor's orders, took a bath.

Three days later she began to feel violently ill. I sat beside her bed until 2:30 in the morning. At four o'clock she complained of severe discomfort. When the doctor arrived at daybreak, he found that she had died a short time before of an embolism of the lungs.

When I went into her room to look at her, her face was tranquil and seemed more beautiful than ever. The night before she had given me a ring she had bought me as a gift for our twenty-fifth anniversary, still seventeen days away. I had asked her why she was presenting it so early and she had replied, "Because I feel I am going to leave you very soon."

But though she knew she would die, she must have put up a struggle for life. Otherwise, why should death have been obliged to surprise her by stealing away her breath while she was asleep?

According to her wish, her coffin was draped with the Mexican Communist flag, and thus she lay in state in the Palace of Fine Arts. Reactionary government officials raised a cry against this display of a revolutionary symbol, and our good friend Dr. Andres Iduarte, Director of the Fine Arts Institute, was fired from his post for permitting it. The newspapers amplified the noise and it was heard throughout the world.

I was oblivious to it all. July 13, 1954, was the most tragic day of my life. I had lost my beloved Frida forever.

When I left, I turned over our house in Coyoacan to the government as a museum for those paintings of mine which Frida had owned. I made only one other stipulation: that a corner be set aside for me, alone, for whenever I felt the need to return to the atmosphere which recreated Frida's presence.

Once out of Coyoacan, I went on a mad tear of the nightclubs. I hate them, and yet I couldn't bear being alone with my thoughts. My only consolation now was my readmission into the Communist Party.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 36183

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Diego Rivera: My Art, My Life. An Autobiography With Gla

EMMA -- I AM HERE STILL

ABOUT NINE MONTHS after Frida's death, I had a recurrence of my cancer of the penis. The Mexican doctors again wanted to amputate. I informed them that though it meant my life, I would still withhold my permission. I had already lived for nearly seventy years, and that was enough if I could not continue to enjoy a normal life.

I now gave up all thought of remarrying; it would be unfair to encumber any desirable woman with whom I could not share a normal social and sexual life.

But my friend Emma Hurtado loved me enough, despite my condition, to want to marry and take care of me. Emma, a magazine publisher, had always been interested in my work. In fact, ten years before, she had opened a gallery for the sole purpose of displaying and selling Rivera paintings. During the ten years we had known one another, a warm feeling of mutuality had always existed between us. Frida was already dead for a year when we decided to become man and wife. Because of our understandable uncertainty, we kept the news of our marriage a secret, even from the most immediate members of our families, for almost a month.

A short time later Emma and I left for Moscow, where I had been invited. As soon as it was learned that I was sick with cancer, the Soviet doctors offered to try to cure me with cobalt treatments not yet available in Mexico. The treatments and in fact everything in Russia cost neither Emma nor me a penny.

I was treated for seven months in the finest hospital in Moscow and then released as cured. The doctors, four-fifths of whom, incidentally, were women, told me that had I come to them four years before at the onset of the cancer, they could have cured me in a month. Before I left the hospital, I was given a complete physical examination and advised that I was now in the pink of health.

During my long stay in bed, I thought often of Emma's kindness, tenderness, and self-sacrifice, and of how very much like Frida she was. It made me happy to feel thus brought back to Frida. Too late now I realized that the most wonderful part of my life had been my love for Frida. But I could not really say that, given "another chance," I would have behaved toward her any differently than I had. Every man is the product of the social atmosphere in which he grows up and I am what I am.

And what sort of man was I? I had never had any morals at all and had lived only for pleasure where I found it. I was not good. I could discern other people's weaknesses easily, especially men's, and then I would play upon them for no worthwhile reason. If I loved a woman, the more I loved her, the more I wanted to hurt her. Frida was only the most obvious victim of this disgusting trait. Yet my life had not been an easy one. Everything I had gotten, I had had to struggle for. And having got it, I had had to fight even harder to keep it. This was true of such disparate things as material goods and human affection. Of the two, I had, fortunately, managed to secure more of the latter than of the former.

As I lay in the hospital, I tried to sum up the meaning of my life. It occurred to me that I had never experienced what is commonly called "happiness." For me, "happiness" has always had a banal sound, like "inspiration." Both "happiness" and "inspiration" are the words of amateurs.

All I could say was that the most joyous moments of my life were those I had spent in painting; most others had been boring or sad. For even with women, unless they were interested enough in my work to spend their time with me while I painted, I knew I would certainly lose their love, not being able to spare the time away from my painting that they demanded. When I had to interrupt my painting to spend days in courting a woman, I would be unhappy for losing the never-to-be-recovered time. Therefore, the women who were best for me were those who also loved painting.

As for my work, whenever I looked at the paintings I had done in the past, I would feel a strong repugnance to each of them. It was like the feeling I had toward a woman who asked me to make love to her after I had tired of her.

So I was unfit to judge my own work. The paintings I most preferred were invariably the most recent ones. Time and change of circumstance invariably led to new forms of expression, new attitudes, and I was constitutionally a revolutionary as opposed to a classical artist. Since everything about me had changed over the past twenty, thirty, and forty years, the work I did in those years now repelled me. Of the three completed works which I found the most interesting, two were recent -- the Lerma Water Supply murals and the wall of the stadium of the new University City. The third was the series of frescoes I had done in the Detroit Arts Institute; but perhaps my appreciation of these was due to the warm reception the people gave them.

Upon my release from the hospital, I began to glow again with plans for the future. After traveling about Europe for a few weeks, I returned with Emma to Mexico.

Emma and I were met at the airport by a crowd of friends and relatives. One of them had written a song for the occasion, "The Story of Diego Rivera's Return." The words were: "The fourth day of April, 1956, Diego Rivera returned to his country. He was cured with cobalt, which is used to make bombs, but which will now be used to make men well. Diego Rivera came back to continue painting in the National Palace. And the end of this ditty serves to make us know that Diego and his wife have returned here, back to their dear country."

The tune was very pretty. My daughters Lupe and Ruth sang it to us as a duet, accompanying themselves with maracas, on the night after Emma and I came home.

One of my greatest excitements now is seeing my newest grandson, Ruth's baby. Ruth calls him Zopito, meaning "Little Frog," because he is fat like me, whom she calls Zoporana, "Big Frog." It's funny that people I love most think I look like a frog, because the city of Guanajuato where I was born means "Many Singing Frogs in Water." I am certainly not a singing frog, though I do burst forth on rare happy occasions into a song.

So now I am home again. With the rest and the superior medical treatment I received in Russia, I should live ten years more. Right now my fingers and I are literally itching to start work on my next mural.

[The last session of dictation took place in the summer of 1956. In the summer of 1957, Diego Rivera went over and approved the first draft of the manuscript. The finished manuscript was read and approved by Emma Hurtado Rivera. -- G. M.]

ABOUT NINE MONTHS after Frida's death, I had a recurrence of my cancer of the penis. The Mexican doctors again wanted to amputate. I informed them that though it meant my life, I would still withhold my permission. I had already lived for nearly seventy years, and that was enough if I could not continue to enjoy a normal life.

I now gave up all thought of remarrying; it would be unfair to encumber any desirable woman with whom I could not share a normal social and sexual life.

But my friend Emma Hurtado loved me enough, despite my condition, to want to marry and take care of me. Emma, a magazine publisher, had always been interested in my work. In fact, ten years before, she had opened a gallery for the sole purpose of displaying and selling Rivera paintings. During the ten years we had known one another, a warm feeling of mutuality had always existed between us. Frida was already dead for a year when we decided to become man and wife. Because of our understandable uncertainty, we kept the news of our marriage a secret, even from the most immediate members of our families, for almost a month.

A short time later Emma and I left for Moscow, where I had been invited. As soon as it was learned that I was sick with cancer, the Soviet doctors offered to try to cure me with cobalt treatments not yet available in Mexico. The treatments and in fact everything in Russia cost neither Emma nor me a penny.

I was treated for seven months in the finest hospital in Moscow and then released as cured. The doctors, four-fifths of whom, incidentally, were women, told me that had I come to them four years before at the onset of the cancer, they could have cured me in a month. Before I left the hospital, I was given a complete physical examination and advised that I was now in the pink of health.

During my long stay in bed, I thought often of Emma's kindness, tenderness, and self-sacrifice, and of how very much like Frida she was. It made me happy to feel thus brought back to Frida. Too late now I realized that the most wonderful part of my life had been my love for Frida. But I could not really say that, given "another chance," I would have behaved toward her any differently than I had. Every man is the product of the social atmosphere in which he grows up and I am what I am.

And what sort of man was I? I had never had any morals at all and had lived only for pleasure where I found it. I was not good. I could discern other people's weaknesses easily, especially men's, and then I would play upon them for no worthwhile reason. If I loved a woman, the more I loved her, the more I wanted to hurt her. Frida was only the most obvious victim of this disgusting trait. Yet my life had not been an easy one. Everything I had gotten, I had had to struggle for. And having got it, I had had to fight even harder to keep it. This was true of such disparate things as material goods and human affection. Of the two, I had, fortunately, managed to secure more of the latter than of the former.

As I lay in the hospital, I tried to sum up the meaning of my life. It occurred to me that I had never experienced what is commonly called "happiness." For me, "happiness" has always had a banal sound, like "inspiration." Both "happiness" and "inspiration" are the words of amateurs.

All I could say was that the most joyous moments of my life were those I had spent in painting; most others had been boring or sad. For even with women, unless they were interested enough in my work to spend their time with me while I painted, I knew I would certainly lose their love, not being able to spare the time away from my painting that they demanded. When I had to interrupt my painting to spend days in courting a woman, I would be unhappy for losing the never-to-be-recovered time. Therefore, the women who were best for me were those who also loved painting.

As for my work, whenever I looked at the paintings I had done in the past, I would feel a strong repugnance to each of them. It was like the feeling I had toward a woman who asked me to make love to her after I had tired of her.

So I was unfit to judge my own work. The paintings I most preferred were invariably the most recent ones. Time and change of circumstance invariably led to new forms of expression, new attitudes, and I was constitutionally a revolutionary as opposed to a classical artist. Since everything about me had changed over the past twenty, thirty, and forty years, the work I did in those years now repelled me. Of the three completed works which I found the most interesting, two were recent -- the Lerma Water Supply murals and the wall of the stadium of the new University City. The third was the series of frescoes I had done in the Detroit Arts Institute; but perhaps my appreciation of these was due to the warm reception the people gave them.

Upon my release from the hospital, I began to glow again with plans for the future. After traveling about Europe for a few weeks, I returned with Emma to Mexico.

Emma and I were met at the airport by a crowd of friends and relatives. One of them had written a song for the occasion, "The Story of Diego Rivera's Return." The words were: "The fourth day of April, 1956, Diego Rivera returned to his country. He was cured with cobalt, which is used to make bombs, but which will now be used to make men well. Diego Rivera came back to continue painting in the National Palace. And the end of this ditty serves to make us know that Diego and his wife have returned here, back to their dear country."

The tune was very pretty. My daughters Lupe and Ruth sang it to us as a duet, accompanying themselves with maracas, on the night after Emma and I came home.

One of my greatest excitements now is seeing my newest grandson, Ruth's baby. Ruth calls him Zopito, meaning "Little Frog," because he is fat like me, whom she calls Zoporana, "Big Frog." It's funny that people I love most think I look like a frog, because the city of Guanajuato where I was born means "Many Singing Frogs in Water." I am certainly not a singing frog, though I do burst forth on rare happy occasions into a song.

So now I am home again. With the rest and the superior medical treatment I received in Russia, I should live ten years more. Right now my fingers and I are literally itching to start work on my next mural.

[The last session of dictation took place in the summer of 1956. In the summer of 1957, Diego Rivera went over and approved the first draft of the manuscript. The finished manuscript was read and approved by Emma Hurtado Rivera. -- G. M.]

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 36183

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: Diego Rivera: My Art, My Life. An Autobiography With Gla

APPENDIX

STATEMENT BY ANGELINE BELLOFF

IT IS TRUE that because of Diego I suffered very much for many years, yet I have never once regretted those ten years we lived together. When Diego first met me, I had just come to France from my home in Russia to study painting.

At that time, I was exceedingly depressed and lonely and afraid. My parents had recently died, and I was all alone in a strange country. Diego was very kind to me then.

It was in 1910 that we first met and fell in love. When, soon after, Diego proposed that we set up housekeeping together, I was fearful; I thought him much too exotic for me. I told him that he should first return to his home in Mexico for one year and then come back to me in Paris. If we found that we still loved each other then, I would gladly accept his proposal.

Diego returned to me as agreed, in 1911. He greeted me with two gold wedding rings sent by his mother. There was never any doubt in my mind, when I accepted my ring, that I would love Diego for the rest of my life. I still wear my ring. You see, it says on it, "D.M.R. to A.B." Of course, we never had a legal marriage ceremony. I guess neither of us thought that necessary.

We lived together as man and wife, and Diego made me ecstatically happy. We made wonderful companions for each other. We traveled through all of Europe together, observing, painting, and loving.

Diego took me to all the art museums and explained everything he had learned about art with infinite patience. He loved me very much in those early years.

His father sent me many warm, tender letters, addressing me as "daughter." In fact, both of his parents continually extended cordial invitations for me to visit Mexico. I have always treasured in my memory how perpetually thrilling life in Paris was at the beginning.

Diego introduced me to all his artist friends, including Matisse and Picasso. He even arranged for Matisse to give me art lessons.

When I became pregnant, Diego began to broach the subject of having our marriage legalized. Yet he would also shout and threaten that if the child cried and disturbed him, he would toss it right out the window. He would say that if the child grew up to be anything like me, he would really cry with grief and disappointment.

All in all, Diego was very annoyed at having to play the role of a father. He insisted that the baby would deprive him of his peace and that besides, we couldn't afford to support another mouth. But then Diego always became maniacal whenever he felt that his work was in danger of being interrupted. He carried on in the same childish manner when he heard that his mother was coming from Mexico just to visit him in Paris.

In one of his periodic tantrums, Diego even threatened to kill himself if she showed up; he said he had no time to devote to her.

Diego has always seemed to do everything unconventionally, to provide himself with more stimulation to paint. He likes to dramatize pain and tragedy, as if he thrives on the emotional delights he experiences from them.

Years later, I realized that I never offered him enough excitement of this kind. I was too agreeable and placid and did not like to manufacture or play up nerve-wracking crises.

After our son was born, Diego had an adventure with the Russian painter Marievna. He left our apartment and went to live with her for five months. When he finally returned home to me, I was too weak-spirited to ask him to leave. Besides, I loved him so terribly I was willing to take him back under any circumstances. But the one thing I have always held against Diego is the way he acted when our one-and-a-half-year-old baby lay sick and dying. From the beginning of the child's illness, Diego would stay away from the house for days at a time, cavorting with his friends in the cafes.

He kept up this infantile routine even during the last three days and nights of our baby's life. Diego knew that I was keeping a constant vigil over the baby in a last desperate effort to save its life; still he didn't come home at all. When the child finally died, Diego, naturally, was the one to have the nervous collapse.

When Diego returned to Mexico for good in 1921, I was obliged to remain behind in Paris. He didn't have enough money for both our fares, so he went alone, promising to send for me soon. Five months later, he did send a cable for me to come to Mexico, but no money. Since I hadn't any myself, I couldn't go. After that, I didn't hear from him again.

I started working, supporting myself by painting for commercial books and magazines.

In 1932, I came to Mexico because I had many friends who told me how beautiful the country was. I did not come to see Diego. In fact, I have seen him only a few times in all the years I have been residing here, and those meetings were accidental.

I have earned my living in Mexico by teaching art to high-school students as well as to private pupils.

I never much cared for the company of Diego's other wives, Lupe Marin and Frida, as we had nothing really in common. I have, however, maintained a friendship with Diego's younger sister, Maria. It was Maria who remarked that, of all Diego's wives, I was the most unique and loved him most truly, since I loved him when he was poor and obscure.

Given the opportunity to live my life over again, I would still choose to spend those same ten years with Diego, despite all the pain I suffered afterwards, because those years were by far the most intense and happy of my whole life.

In this reminiscence of my life with Diego, I do not mean to say anything derogatory about him. He has never been a vicious man, but simply an amoral one. His painting is all he has ever lived for and deeply loved. And to his art, he has given the fidelity he could never find within him to give to a woman.

STATEMENT BY LUPE MARIN

WHEN I FIRST MET DIEGO, I thought he was very ugly. Nevertheless, I fell very much in love with him at that first meeting. I think he fell in love with me then, too. Despite what everyone has said in the past, when Diego was living with me, he had no other woman. As a husband, he was wonderful, always being muy hombre.

During the time we were married, we were quite poor, and many times we did not have enough to eat. Whatever money Diego made, he spent on his idols or donated to the C.P. He never thought of any practical ways to spend his money. Such prosaic things as food, clothing, or the rent were his last considerations.

It seems that my whole life was centered around Diego then. I accompanied him to the buildings where he was painting and remained at his side through all the day. I left him only to prepare his hot lunches, which I served to him on the scaffold.

During the seven years of our marriage, we had many arguments. The more furious and violent I became, the more Diego laughed and ignored me. After our girls were born, he gave me very little money to support them; otherwise, he was a good papa.

I think that the nudes Diego did of me are excellent, but I feel that they are independent of me, that each has its own personal identity. Of course, I believe that next to Picasso, Diego is the greatest contemporary painter in the world.

After Diego left me, I had an unfortunate marriage which lasted three years and have not remarried since. I had been tied down for so long to Diego, and then Cuesta, that I came to value my freedom more than any possible new husband. Besides, after those two marriages, I completely lost the faculty to love. That deficiency is still in me.

Since my marriages, I have earned my living as a writer, sewing teacher, and high-fashion designer. I have written two books, in parts of which I described my marriages, using fictitious names, naturally.

By the time Diego married Frida, my initial deep hurt had worn off, and I even attended the wedding. It has been written about me that Diego and I were separated once because I found him making love to my sister. That is not true; it was Frida's sister he made love to, and that's why Frida left him once, too. The real reason we parted was that he carried on so flagrantly with the model Tina Modotti. I couldn't stand that! I was beyond being angry. I felt deeply injured and deceived.

Diego has always paid much attention to women throughout his life, but he has always been respectful toward them. However, I don't believe for a minute that he likes any of them for themselves, for if he did, he would be faithful to them. One thing Diego truly likes about women is the money they can give him, since the majority of his mistresses have been women of great wealth. It is my opinion that they flock around him so because his fame, not he himself, is so interesting.

But I still love Diego, both as a friend and as the father of my children. My older daughter, Lupe, while not being exactly like either of us, has some of the characteristics of Diego. I am violent-tempered, but Lupe is more easygoing, like Diego. Ruth is closer to possessing all of the qualities of her father's temperament.

Over the years Diego has not changed much, except in one respect. As he has gotten older, he has gradually become cleaner. He hardly ever bathed when we lived together, but he bathes every day now because he knows that women hate a dirty man, and an old man has to be much more fastidious than a young one. In this respect he has begun to resemble a gentleman.

STATEMENT BY FRIDA KAHLO

(Frida was ill and already near death when I met with her. Aside from a few interesting observations about Rivera, which are included at the end of her statement here, I found the notes of my interview with her less satisfactory than an article she had prepared earlier, in connection with the half-century exhibition of Rivera's work by the Fine Arts Institute of Mexico City. The article, brought to my attention by Rivera himself, was published by the Institute in a souvenir book, and is reproduced with permission of the Institute. -- G.M.)

I WARN YOU that in this picture I am painting of Diego there will be colors which even I am not fully acquainted with. Besides, I love Diego so much I cannot be an objective spectator of him or his life ... I cannot speak of Diego as my husband because that term, when applied to him, is an absurdity. He never has been, nor will he ever be, anybody's husband. I also cannot speak of him as my lover because to me, he transcends by far the domain of sex. And if I attempt to speak of him purely, as a soul, I shall only end up by painting my own emotions. Yet considering these obstacles of sentiment, I shall try to sketch his image to the best of my ability.

Growing up from his Asiatic-type head is his fine, thin hair, which somehow gives the impression that it is floating in air. He looks like an immense baby with an amiable but sad-looking face. His wide, dark, and intelligent bulging eyes appear to be barely held in place by his swollen eyelids. They protrude like the eyes of a frog, each separated from the other in a most extraordinary way. They thus seem to enlarge his field of vision beyond that of most persons. It is almost as if they were constructed exclusively for a painter of vast spaces and multitudes. The effect produced by these unusual eyes, situated so far away from each other, encourages one to speculate on the ages-old oriental knowledge contained behind them.

On rare occasions, an ironic yet tender smile appears on his Buddha-like lips. Seeing him in the nude, one is immediately reminded of a young boy-frog standing on his hind legs. His skin is greenish-white, very like that of an aquatic animal. The only dark parts of his whole body are his hands and face, and that is because they are sunburned. His shoulders are like a child's, narrow and round. They progress without any visible hint of angles, their tapering rotundity making them seem almost feminine. The arms diminish regularly into small, sensitive hands ... It is incredible to think that these hands have been capable of achieving such a prodigious number of paintings. Another wonder is that they can still work as indefatigably as they do.

Diego's chest -- of it we have to say, that had he landed on an is-land governed by Sappho, where male invaders were apt to be executed, Diego would never have been in danger. The sensitivity of his marvelous breasts would have insured his welcome, although his masculine virility, specific and strange, would have made him equally desired in the lands of these queens avidly hungering for masculine love.

His enormous belly, smooth, tightly drawn, and sphere-shaped, is supported by two strong legs which are as beautifully solid as classical columns. They end in feet which point outward at an obtuse angle, as if moulded for a stance wide enough to cover the entire earth.

He sleeps in a foetal position. In his waking hours, he walks with a languorous elegance as if accustomed to living in a liquefied medium. By his movements, one would think that he found air denser to wade through than water.

I suppose everyone expects me to give a very feminine report about him, full of derogatory gossip and indecent revelations. Perhaps it is expected that I should lament about how I have suffered living with a man like Diego. But I do not think that the banks of a river suffer because they let the river flow, nor does the earth suffer because of the rains, nor does the atom suffer for letting its energy escape. To my way of thinking, everything has its natural compensation.

***

To Diego painting is everything. He prefers his work to anything else in the world. It is his vocation and his vacation in one. For as long as I have known him, he has spent most of his waking hours at painting: between twelve and eighteen a day.

Therefore he cannot lead a normal life. Nor does he ever have the time to think whether what he does is moral, amoral, or immoral.

He has only one great social concern: to raise the standard of living of the Mexican Indians, whom he loves so deeply. This love he has conveyed in painting after painting.

His temperament is invariably a happy one. He is irritated by only two things: loss of time from his work, and stupidity. He has said many times that he would rather have many intelligent enemies than one stupid friend.

STATEMENT BY EMMA HURTADO

I HAVE KNOWN DIEGO for twelve years, in the last two of which I have been his wife.

I married Diego when he was very sick with cancer, just shortly before we went to Russia for him to be treated. At that time I had no idea whether he would live or die.

Upon our arrival, Diego was hospitalized from September, 1955, until the end of January, 1956, practically all of which time he was in bed.

I was at the hospital with him every day from eight in the morning until eight at night. It was an exceptional arrangement, which the hospital permitted because we had traveled from so far away.

I lived in a hotel near the hospital. It was not easy to be all alone in a foreign country, and with no knowledge of the language, especially in this terrible situation. There was the continually nerve-wracking task of dealing with the newspaper people, all of whom seemed to be momentarily expecting some dramatic announcement. One reporter, more impatient than the rest, wrote that Diego and I were being held prisoner by the government. How he could have reached such a conclusion I cannot imagine, for all during our stay we received nothing but attention and courtesy.

Diego was an extraordinarily good patient. He made no objection to anything the nurses or doctors suggested. At the beginning, he sketched everything around him: patients, doctors, nurses, and apparatus. He always kept a sketch book and pencil beside his bed. After he had received many cobalt treatments, however, he became very weak, so weak in fact, that he couldn't draw a single line.

This made him despondent, and considering it a bad sign, the doctors arranged to move him to a hotel room where he could view the November 7th parade in Red Square. The parade excited him so, that he moved away from his chair and started making sketches. I was relieved to see this change of spirit, as were his doctors.

By January, he was well again and painting furiously and with much gusto. Within the next six months, he completed over four hundred pieces of work in Russia, Germany, Czechoslovakia, and Poland, where we traveled briefly before flying home. After arriving in Mexico, we went to Acapulco, where he did many marvelous oils, water colors, and sketches.

We had an exhibition of all this work, here in Mexico, in November, 1956. The show was such a success that practically every piece was sold.

As a husband, Diego has always been very good to me, even the times when he was sick and uncomfortable. Of course he still has many other women friends. But for a man like Diego, that is necessary; he needs to feel many different kinds of emotions in order to be able to paint as he does. And yet, I must say, it is the women who are always chasing after him, not he after them. He is always polite and attentive to them; they respond to his chivalry; and before he is fully aware of it, he is already involved.

The more he lives the greater grows the desire of collectors to buy his paintings. It is no longer a question of what he says or does, or what the world thinks of him. He is already a classic. And his greatness insures him against everything.

STATEMENT BY ANGELINE BELLOFF

IT IS TRUE that because of Diego I suffered very much for many years, yet I have never once regretted those ten years we lived together. When Diego first met me, I had just come to France from my home in Russia to study painting.

At that time, I was exceedingly depressed and lonely and afraid. My parents had recently died, and I was all alone in a strange country. Diego was very kind to me then.

It was in 1910 that we first met and fell in love. When, soon after, Diego proposed that we set up housekeeping together, I was fearful; I thought him much too exotic for me. I told him that he should first return to his home in Mexico for one year and then come back to me in Paris. If we found that we still loved each other then, I would gladly accept his proposal.

Diego returned to me as agreed, in 1911. He greeted me with two gold wedding rings sent by his mother. There was never any doubt in my mind, when I accepted my ring, that I would love Diego for the rest of my life. I still wear my ring. You see, it says on it, "D.M.R. to A.B." Of course, we never had a legal marriage ceremony. I guess neither of us thought that necessary.

We lived together as man and wife, and Diego made me ecstatically happy. We made wonderful companions for each other. We traveled through all of Europe together, observing, painting, and loving.

Diego took me to all the art museums and explained everything he had learned about art with infinite patience. He loved me very much in those early years.

His father sent me many warm, tender letters, addressing me as "daughter." In fact, both of his parents continually extended cordial invitations for me to visit Mexico. I have always treasured in my memory how perpetually thrilling life in Paris was at the beginning.

Diego introduced me to all his artist friends, including Matisse and Picasso. He even arranged for Matisse to give me art lessons.

When I became pregnant, Diego began to broach the subject of having our marriage legalized. Yet he would also shout and threaten that if the child cried and disturbed him, he would toss it right out the window. He would say that if the child grew up to be anything like me, he would really cry with grief and disappointment.

All in all, Diego was very annoyed at having to play the role of a father. He insisted that the baby would deprive him of his peace and that besides, we couldn't afford to support another mouth. But then Diego always became maniacal whenever he felt that his work was in danger of being interrupted. He carried on in the same childish manner when he heard that his mother was coming from Mexico just to visit him in Paris.

In one of his periodic tantrums, Diego even threatened to kill himself if she showed up; he said he had no time to devote to her.

Diego has always seemed to do everything unconventionally, to provide himself with more stimulation to paint. He likes to dramatize pain and tragedy, as if he thrives on the emotional delights he experiences from them.

Years later, I realized that I never offered him enough excitement of this kind. I was too agreeable and placid and did not like to manufacture or play up nerve-wracking crises.

After our son was born, Diego had an adventure with the Russian painter Marievna. He left our apartment and went to live with her for five months. When he finally returned home to me, I was too weak-spirited to ask him to leave. Besides, I loved him so terribly I was willing to take him back under any circumstances. But the one thing I have always held against Diego is the way he acted when our one-and-a-half-year-old baby lay sick and dying. From the beginning of the child's illness, Diego would stay away from the house for days at a time, cavorting with his friends in the cafes.

He kept up this infantile routine even during the last three days and nights of our baby's life. Diego knew that I was keeping a constant vigil over the baby in a last desperate effort to save its life; still he didn't come home at all. When the child finally died, Diego, naturally, was the one to have the nervous collapse.

When Diego returned to Mexico for good in 1921, I was obliged to remain behind in Paris. He didn't have enough money for both our fares, so he went alone, promising to send for me soon. Five months later, he did send a cable for me to come to Mexico, but no money. Since I hadn't any myself, I couldn't go. After that, I didn't hear from him again.

I started working, supporting myself by painting for commercial books and magazines.

In 1932, I came to Mexico because I had many friends who told me how beautiful the country was. I did not come to see Diego. In fact, I have seen him only a few times in all the years I have been residing here, and those meetings were accidental.

I have earned my living in Mexico by teaching art to high-school students as well as to private pupils.

I never much cared for the company of Diego's other wives, Lupe Marin and Frida, as we had nothing really in common. I have, however, maintained a friendship with Diego's younger sister, Maria. It was Maria who remarked that, of all Diego's wives, I was the most unique and loved him most truly, since I loved him when he was poor and obscure.

Given the opportunity to live my life over again, I would still choose to spend those same ten years with Diego, despite all the pain I suffered afterwards, because those years were by far the most intense and happy of my whole life.

In this reminiscence of my life with Diego, I do not mean to say anything derogatory about him. He has never been a vicious man, but simply an amoral one. His painting is all he has ever lived for and deeply loved. And to his art, he has given the fidelity he could never find within him to give to a woman.

STATEMENT BY LUPE MARIN