by Jane Hunter*

Winter 1990

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Throughout George Bush's presidential campaign and well into the first year of his presidency, polls consistently showed that a majority of the U.S. public did not believe Bush was telling the truth about his role in the Iran/contra affair. Of course, they were right -- he wasn't.

Bush's plea of ignorance of the arms sales to Iran, that "I was out of the loop," was widely repeated, and always certain to get a laugh. However, we should not forget that in reality, George Bush attended all but one of the important White House meetings on the subject. (The one he missed conflicted with the December 7, 1985 Army-Navy football game.)

Secretary of State Shultz testified before the Iran/contra committee that, at a key January 6, 1986 meeting about the "finding" authorizing arms sales to Iran, Bush had not supported Shultz's own vehement opposition to the plan. This undercut Bush's assertion that he had had "reservations" about trading arms for hostages but just didn't think it was proper to reveal the counsel he had given President Reagan on the subject. [1]

During the course of investigating Bush's role in the Iran/contra affair both the U.S. Congress and several news agencies revealed that, contrary to his assertions of innocence, the president-to-be was up to his knees in "deep doo-doo."

The Harari Network

One of the most compelling revelations came in 1988 and related to the connection between Donald Gregg and the so-called "Harari network." The Harari network consisted of Israelis, Panamanians and U.S. citizens set up by the Reagan administration and the government of Israel in 1982 to run a secret aid program for the contras. Its namesake was Mike Harari, a longtime Mossad official, who since around 1979 has served as Israel's agent in Panama. [2] Still reliably reported to be a senior intelligence operative. [3] Harari supervises Gen. Manuel Antonio Noriega's security arrangements and is credited with helping the general withstand a coup sponsored by the Reagan administration in 1988. Harari also acts as a financial adviser and business partner to Noriega. [4] Following the October 1989 coup attempt, Harari reportedly took over the day-to-day supervision of Panama's military intelligence. [5]

The existence of the Harari network became publicly known in April 1988, during testimony before the Subcommittee on Narcotics, Terrorism and International Operations of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, which was looking into the connections between the war against Nicaragua and drug trafficking. It is, however, possible that the Congressional Iran/contra investigators knew all about this organization but, because the committee made a decision not to examine anything prior to 1984, it easily avoided exposing it.

Between 1975 and 1977, Sharon was a private citizen who was trying to build a fortune dealing in arms in Central America. He had a network of people working with him there, one being the disgraced Mossad agent Mike Harari, who had just left Israel because of his failure in the "Moroccan Waiter Affair," where the wrong man was shot dead in Lillehammer, Norway, during an attempted hit on Ahmed Salame, a Palestinian who had been involved in the massacre of Israeli athletes at the 1972 Olympic Games in Munich. Harari was a close associate of Panama's military intelligence chief, Manuel Noriega.

Sharon's network had been able to provide military equipment from Israel to various Central American countries, including El Salvador, Guatemala, Panama, Costa Rica, and even Mexico. This was never official Israeli government policy, and it was frowned upon by the cabinet itself, but Sharon was too wild a goose for anybody to handle. So Sharon's private network bought their weapons from Israeli government factories and got their export licenses from the Israeli government. Gates had developed a professional interest in the arms network that Sharon and his former intelligence cowboys were operating in Central America. By 1981, Sharon and Harari were running what Harari described as more of a CIA network than an Israeli operation -- and were filling their private bank accounts at the same time.

It was in 1981 that they started supplying a secret army in Central America, the contras, who were trying to destabilize and eventually bring about the downfall of the Sandinista government of Nicaragua, which had come to power in 1979. The contras did not have any money -- Congress was not then willing to fund them -- and desperately needed cash to buy their arms.

Sharon, with all his power, could not force the prime minister or the leaders of the Israeli intelligence community to pay for weapons from the slush fund that had grown out of the Iran arms sales. So, with the backing of Gates and the CIA, some members of the group created their own fund. They did this, according to Harari, by transporting cocaine from South America to the United States via Central America. A major player was Manuel Noriega, who had known George Bush since he had been the CIA chief in the mid-1970s. Hundreds of tons of cocaine poured into the United States, and another handy slush fund was created.

Because of the close relationship between Gates and Sharon and the special relationship between Robert McFarlane and Rafi Eitan, the strategic U.S./Israeli agreement sought by Sharon was reached. The signing of the strategic agreement by Sharon and the U.S. was made public, but the contents were kept secret and are still not available through any Freedom of Information Act requests.

However, one part of it was that any U.S. arms sold to Israel involving technology that was 20 years old or more could be resold at the discretion of the Israeli government. The agreement was very loosely worded -- it could be interpreted to mean that Israel was allowed to resell brand-new American weapons as long as the technology behind them was at least 20 years old.

This was our first ploy to overcome American denials, if any. If Israel were discovered to be selling arms to the Iranians, we would simply brandish the agreement the Americans had signed ... with its gaping loophole.

Our second protection involved the money from the arms sales -- when letters of credit or cash were paid to us to purchase U.S. arms, we simply and quite blatantly ran the sums through U.S. banks.

A letter of credit from the Iranian government would be issued to an Israeli "front" company by a European-based Iranian company through the London or Paris branch of Iran's Bank Melli. It would be endorsed by the National Westminster Bank in England, and we would then ask for it to be transferred to an American bank. Favorites were the Chicago-Tokyo Bank in Chicago, the Chemical Bank in New York, Bank One in Ohio, and the Valley National Bank of Arizona. Then the banks would have to explain these letters of credit, in U.S. dollars, to the U.S. Treasury if they were to accept them. According to U.S. Treasury regulations, letters of credit for sums in excess of $10,000 had to be approved by Treasury.

Since the sales were a U.S.-sanctioned operation, the CIA would have to ensure that Treasury issued an acceptance. Once the letter of credit was approved, it was moved back again to Europe. Except for the John Street operations in 1981 -82, this was to be the way almost all the American-supplied arms sales to Iran were handled from late 1981 until late 1987.

-- Profits of War: Inside the Secret U.S.-Israeli Arms Network, by Ari Ben-Menashe

In April 1988 Jose Blandon, a former intelligence aide to Gen. Noriega told the narcotics subcommittee, headed by Sen. John Kerry (Dem.-Mass.), that the Harari network had brought East bloc arms to Central America for the Nicaraguan contras and had smuggled cocaine from Colombia to the United States via Panama. Blandon testified that on occasion, the aircraft and Costa Rican airstrips the Harari network used for arms deliveries to the contras also carried narcotics shipments north to the U.S. [6]

Three days after Blandon testified, ABC News interviewed a U.S. pilot, who said he had helped purchase and deliver the Harari network's arms and had also flown drugs from Colombia to Panama. Using the pseudonym "Harry," the pilot said he had regarded Israel as his primary employer and the U.S. as his secondary employer. [7]

A short time later, Richard Brenneke, who was also involved in the Harari network, went public. Brenneke is an Oregon businessman who claims to have worked for both the Mossad and the CIA. Brenneke said he was recruited to work with the Harari network by Pesakh Ben-Or, the Mossad station chief in Guatemala. When he asked if the operation was approved by the U.S., Brenneke claims that Ben-Or gave him Donald Gregg's phone number in Washington, DC to call to verify that it was. He said that when he called Gregg on November 3, 1983 [8] Gregg told him that he should "by all means cooperate." [8]

ABC News reported that Israel had provided $20 million start-up capital for the Harari network and was later reimbursed from U.S. covert operations funds. Brenneke claimed that the funding, aircraft, and occasionally pilots for the Harari network and its counterpart in Honduras, dubbed the "Arms Supermarket," were supplied by the Medellin Cartel. [9]

According to United Press International, the Arms Supermarket consisted of three warehouses in San Pedro Sula, Honduras which were filled with Eastern bloc arms. Brenneke stated that it was established "at the request of the Reagan administration" and "initiated jointly by operatives of the Israeli Mossad, senior Honduran military officers now under investigation for drug trafficking, and CIA-connected arms dealers." [10]

Brenneke, however, claims the Supermarket was a separate operation from the Harari network. This was because Pesakh Ben-Or did not get along with Mario Del Amico and Ron Martin, the CIA arms dealers connected to the Supermarket. [11]

Credit: Jean Marie Simon

Pesakh Ben-Or, Mossad Station Chief in Guatemala.

In a May 1988 article about the Arms Supermarket, Newsweek said it had possession of a 1986 report prepared for Oliver North by an arms dealer ''warning bluntly that disclosure of 'covert black money' flowing into Honduras to fund military projects 'could damage Vice President Bush."'[12]

Both Brenneke and ABC News identified Felix Rodriguez, the former CIA official who managed secret contra supply operations from Ilopango Air Base in El Salvador, as the Harari network's U.S. contact in Central America. [13]

Brenneke said that in 1985, after becoming disenchanted with the drug smuggling element of the operation, he called Gregg to warn him about the Harari network's connection to the Medellin Cartel. Brenneke claims that Gregg told him "You do what you were assigned to do. Don't question the decisions of your betters." [14]

Making Brenneke's allegations about Gregg more plausible are classified documents, which, according to Steven Emerson, author of Secret Warriors, "show that the National Security Council had assumed a new operational role as early as 1982, with Gregg serving in a key role as a pivotal player in the NSC 'offline' links to the CIA." [15]

"By early 1983," wrote Emerson, "officials of the NSC and the vice president's staff assumed authority over Central America policy having wrested control over it from the State Department." [16] Gregg was a lifelong CIA officer before going to work as a member of the NSC staff between 1979 and 1981, after which he became Bush's national security adviser.

In the Spring of 1983, the network began to turn its attention toward beefing up the Administration's capacity to promote American support for the Democratic resistance in Nicaragua and the fledgling democracy in El Salvador. This effort resulted in the creation of the Office of Public Diplomacy for Latin America and the Caribbean in the Department of State (S/LPD), headed by Otto Reich.

On May 25, 1983, Secretary of State George P. Schultz, in an effort to head off the creation of S/LPD, wrote a memorandum to the President asking for the establishment of "simple and straight-forward management procedures." [Schultz testimony, Exhibit 69a supra]. The memorandum to the President followed a discussion between the President and Schultz earlier in the day. In the memo Schultz said:"… Therefore, what we discussed was that you will look to me to carry out your policies. If those policies change, you will tell me. If I am not carrying them out effectively, you will hold me accountable. But we will set up a structure so that I can be your sole delegate with regard to carrying out your policies.

"… What this means is that there will be an Assistant Secretary acceptable to you (and you and I have agreed on Tony Motley) who will report to me and through me to you. We will use Dick Stone as our negotiator, who, in conjunction with Tony, will also report solely to me and through me to you. Similarly, there will be an inter-agency committee, but it will be a tool of management and not a decision-making body. I shall resolve any issues and report to you."

The President responded with a memorandum, which stated in part:Success in Central America will require the cooperative effort of several Departments and agencies. No single agency can do it alone nor should it. Still, it is sensible to look to you, as I do, as the lead Cabinet officer, charged with moving aggressively to develop the options in coordination with Cap, Bill Casey and others and coming to me for decisions. I believe in Cabinet government. It works when the Cabinet officers work together. I look to you and Bill Clark to assure that that happens." [Schultz Testimony, Exhibit 69B].

Attached to the memo was a chart placing the NSC between the Secretary of State and the President for the management of Central American strategy. Schultz had not only lost the battle to prevent the establishment of the office, he also accepted the NSC-sponsored candidate to run the office, and accepted the fact that Reich would report directly to the NSC and not through the Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs.

-- An unpublished draft chapter of the congressional Iran-Contra investigation, that was suppressed as part of the deal to get three moderate Republican senators to sign on to the final report and give the inquiry a patina of bipartisanship.

When Vice President Bush challenged Richard Brenneke's credibility, Brenneke produced documentation that seemed to substantiate some of his claims. [17] Unfortunately, all he had to document his conversations with Gregg were his phone records.

In fact, Bush was so threatened by Brenneke's charges that he and his supporters decided a strong counter-attack was in order. Bush personally accused Sen. Kerry of allowing "slanderous" allegations to leak from his committee, which Brenneke had testified before in closed session. Bush also exclaimed that Newsweek, which used Brenneke as one of its sources for a report on the Arms Supermarket, was printing "garbage." Of Brenneke, Bush said "The guy who they are quoting is the guy who is trying to save his own neck." [18] It is important to note, however, that Richard Brenneke has never been indicted on any criminal charges (compared to Oliver North, Robert McFarlane, and John Poindexter who all worked closely with George Bush).

Just Say No To Quid Pro Quo

After Bush was safely ensconced in the presidency it was revealed that in March 1985 he had served as an emissary to Honduras, as part of a Reagan administration effort to keep that government cooperating with its illicit support of the contras. Bush was sent a copy of a February 19, 1985 memorandum from National Security Adviser Robert McFarlane to President Reagan, in which McFarlane advised accelerating the flow of economic and military aid to Honduras as "incentives for them to persist in aiding the freedom fighters." [19] A second memo by McFarlane, dated the same day, suggested sending an emissary to then Honduran President Roberto Suazo Cordoba to privately offer this quid pro quo. Another memo which gave details of this proposal was written by North to McFarlane the following day and had a notation by John Poindexter saying, 'We want VP to also discuss this matter with Suazo." [20]

The memos were two of six documents that were released during North's trial but which the Congressional committees investigating the Iran/contra affair never received. Another document, summarizing a phone conversation between Reagan and Suazo, had a notation indicating that Bush was supposed to receive a copy. [21]

Rep. Lee Hamilton (Dem.-Ind.), who chaired the House side of the joint Iran/contra committee, said the missing documents were "about as clear a statement of quid pro quo as you'll ever see in a government document" and did not discount the possibility that they would be cause to reopen the Iran/contra investigation. [22]

Not surprisingly, when the Senate intelligence committee did investigate the matter of the withheld documents, they concluded there was "no evidence to suggest" that the documents "had been deliberately and systematically withheld by the White House, or persons within the White House, from the Congressional investigating committees." [23]

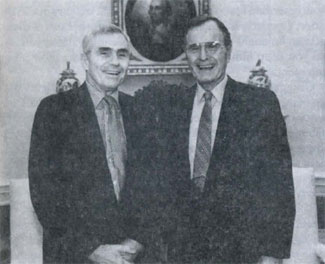

Credit: The White House

Donald Gregg and his good friend, George Bush.

President Bush denied discussing a quid pro quo with Suazo and he refused to respond to the stories while North's trial was underway. Michael G. Kozak, acting Assistant Secretary of State for Inter-American Affairs, told Congress that from his review of the documents, the plan to have Bush carry the message to Honduras had been killed. [24] He said he had a secret cable proving that Bush never explicitly linked contra aid and assistance to Honduras. However, the Council on Hemispheric Affairs pointed out that the cable, written by then Ambassador John Negroponte -- himself a main Iran/contra player -- would have been routinely sanitized (in this case, probably by Donald Gregg) before it was consigned to the permanent files. [25]

None of this back and forth even touched on a paragraph contained in a document submitted in Oliver North's trial. Referred to as an official admission of facts, the document summarized classified material North was not permitted to introduce. The government agreed, for the purposes of the trial, that the 107 assertions contained in its 42 pages, were true. The 79th stipulation recounts preparations for a Bush mission to Honduras:

In mid-January 1986, the State Department prepared a memorandum for Donald Gregg (the Vice President's national security adviser) for Vice President Bush's meeting with President [Jose] Azcona. According to DoS [Department of State], one purpose of the meeting was to encourage continued Honduran support for the contras. The memorandum alerted Gregg that Azcona would insist on receiving clear economic and social benefits from its cooperation with the United States. Admiral Poindexter would meet privately with President Azcona to seek a commitment of support for the contras by Honduras. DoS suggested that Vice President Bush inform President Azcona that a strong and active contra army was essential to maintain pressure on the Sandinistas, and that the United States government's intention to support the contras was clear and firm. [26]

Gregg's Reward

Donald Gregg's reward for his loyalty to George Bush, as well as for his role in running the Nicaraguan contras, was to be nominated as ambassador to South Korea. Members of the Senate Foreign Affairs Committee had pleaded with the administration to withdraw Gregg's nomination, warning that to press on risked a reopening of the Iran/contra affair and an unraveling of the newly-forged ''bipartisan consensus" on foreign policy. The administration could hardly have withdrawn the nomination, as that would have been regarded as an acknowledgment of President Bush's own complicity in the illegal resupply of the contras.

According to Sen. Alan Cranston (Dem.-Calif.), Gregg's diplomatic nomination came after "key members" of the Senate Intelligence Committee blocked a move to appoint him to a "top CIA post." Gregg claimed that he lost out on the CIA job when discreet inquiries had revealed that his nomination to a top CIA post would embroil the Agency in questions over his role in the Iran/contra affair. [27]

Incredibly, when asked during his confirmation hearings why Bush had nominated him as Ambassador to Korea rather than taking him to the White House, Gregg said that Bush had a marked aversion to seeing the NSC take on an operational role. [28] Did he mean to imply that his assignment in South Korea was operational? Reflecting widespread disappointment with the nomination, an editorial in a South Korean newspaper asked whether Gregg's return to the nation where he had been CIA station chief from 1973-75 meant that "the U.S. regards Korea not as a diplomatic but as an intelligence and operations target." [29]

"If Gregg was lying, he was lying to protect the president, which is different from lying to protect himself."

The confirmation hearings that stretched over May and June 1989 were a test of strength, with the committee destined from the start to be the loser. Speaking -- under oath -- in an indifferent monotone Gregg baited Alan Cranston, chairman of the Foreign Relations Subcommittee on East Asian and Pacific Affairs and his principal interrogator, with outrageous answers. For example, after denying that in 1985 he met with Oliver North and Col. James Steele -- then the chief U.S. military adviser in El Salvador -- to discuss the contra operation, Gregg coolly absorbed the news that Steele had confirmed the meeting. [30]

An indignant Cranston charged: "Your career training in establishing secrecy and deniability for covert operations and your decades-old friendship with Felix Rodriguez apparently led you to believe that you could serve the national interest by sponsoring a freelance operation out of the Vice President's office." [31]

Copters not Contras

The greatest moment of absurdity (and outright lying) came when Gregg offered what he called a "speculative explanation" for a reference to a mention of "resupply of the contras" in a May 1, 1986 memo, prepared for a meeting between Bush and Rodriguez. It was "possible," Gregg said, that it ''was a garbled reference to resupply of copters instead of resupply of contras." Later, Gregg remarked to reporters, "I don't know how it went over, but it was the best I could do." [32]

Cranston failed to question Gregg on a key point. Steven Emerson reported that he had seen a March 1983 memo prepared by Gregg which accompanied a plan to organize a "search-and-destroy air team." The plan was drafted by Felix Rodriguez and contained a map which "strongly suggested that targets inside Nicaragua would be attacked." Emerson said these "still classified" documents bore the handwritten approval of then National Security Adviser William Clark. [33]

Cranston repeatedly tried to crack Gregg's facade and Gregg continued to deny any connection to the contras or ever having discussed the mercenaries with Bush. He didn't even back away from his earlier statement that Bush had learned of the secret resupply network from an interview Gregg gave the New York Times in December 1986.

Cranston wondered aloud how Gregg didn't know that Rodriguez was involved with the contras when the NSC staff, the State Department, and Gen. Paul Gorman, head of the U.S. Southern Command, all knew that the illegal contra aid operation was Rodriguez's real priority in Central America. Gregg said he had to agree with Cranston's (heavily sarcastic) interpretation of his testimony: that Oliver North and his longtime friend Felix Rodriguez were conspiring against him! At his trial Oliver North testified that "I was put in touch with Mr. Rodriguez by Mr. Gregg of the Vice President's office" [34] and that Gregg knew about the arms shipments. During his confirmation hearing Gregg said North's statements were "just not true." [35]

Hopeless as all of this was, Cranston's interrogation hovered around the fundamental question. Recalling Bush's statement in October 1986 that Felix Rodriguez was not working for the U.S. government and Gregg's own knowledge that Rodriguez had received help from the U.S. military in El Salvador, Cranston asked Gregg, "Did you inform Bush of those facts so he could make calculated misleading statements, or did you keep him in the dark so he could make misleading statements?"

Gregg evaded the question, contending that Rodriguez was not being paid a government salary but was living off his CIA pension. He also insisted that Bush "made no misleading statements." [36] During the hearings, Cranston had accused Gregg of using Rodriguez's work with the Salvadoran government as "a cover story," to which Gregg replied that Cranston was providing "a rather full-blown example of a conspiracy theory." [37]

That Donald Gregg had blithely lied under oath was apparent to everyone. Even one of his Republican supporters on the committee, Sen. Richard Lugar (Rep.-Ind.), said that some of Gregg's testimony "certainly strains belief." Another Republican, Senator Mitch McConnell of Kentucky, noted -- perhaps disingenuously, certainly inaccurately -- that other Bush ambassadorial appointments of individuals more heavily involved in the Iran/contra affair than Gregg had "sailed through." [38]

Ultimately it was power that overrode perceptions, not to mention truth. The senators did not really want to challenge Bush, whose popularity was soaring. Just to get the administration to release relevant documents it had been withholding, Cranston had to promise to schedule a vote on Gregg. [39]

Three Democrats on the Foreign Relations Committee joined all the Republicans, in voting to report the nomination favorably to the full Senate. One of the Democrats, Terry Sanford of North Carolina, confirmed Cranston's explanation of his vote -- that he was afraid "the path would lead to Bush." "If Gregg was lying," said Sanford, "he was lying to protect the president, which is different from lying to protect himself." [40] Oh, really?

_______________

Notes:

* Jane Hunter is the author of several books and contributor to several foreign newspaper as well as the editor of the independent monthly report Israeli Foreign Affairs, which is available for $20 per year from Israeli Foreign Affairs, P.O. Box 19580, Sacramento, CA 95819.

1. Joel Brinkley, "Bush's Role in Iran Affair: Questions and Answers," New York Times, January 29, 1988.

2. For more on Harari and the Harari Network, see Israeli Foreign Affairs, May 1987, and February, March, April, May and June 1988.

3. Andrew Cockburn, "A friend in need," Independent, March 19, 1988.

4. Uri Dan, "Israeli is Power Behind Noriega," New York Post, July 11, 1988.

5. Stewart M. Powell and John P. Wallach, "Israeli Working For Noriega," San Francisco Examiner, October 22, 1989.

6. Hearings of the Narcotics, Terrorism, and International Operations Subcommittee of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, April 4, 1988.

7. Transcript, ABC News, April 7, 1988.

8. Jim Redden, "Burning Bush," Willamette Week (Portland, OR), July 14-20, 1988; United Press International (UPI), May 15, 1988; Robert Parry and Rod Nordland, "Guns for Drugs?," Newsweek, May 23, 1988.

9. ABC News interview, May 28, 1988.

10. UPI, May 15, 1988.

11. Interview with Brenneke, Israeli Foreign Affairs, June 1988.

12. Newsweek, May 23, 1988.

13. "Arms, Drugs and the Contras," a Frontline television documentary aired on U.S. Public Television stations in May 1988, also identified Rodriguez as the contact.

14. Parry and Nordland, op. cit., n. 8.

15. Steven Emerson, Secret Warriors (New York: G. P. Putnam's Sons, 1988), p. 129.

16. Ibid, pp. 125-26.

17. Brenneke's documents of his activities are reproduced in The Brenneke Report: An Assessment of the International Center's Investigation, Washington, DC, August 25, 1988. (Brenneke worked for the International Center for Development Policy after he went public.) For a more detailed examination of Brenneke's veracity, see Israeli Foreign Affairs, October 1988 and Jane Hunter, "A Renaissance Man," NACLA, Report on the Americas, September/October 1988. It must also be said that some analysts do not believe that Jose Blandon is the essence of credibility, either, even though his testimony was less disconcerting than Brenneke's.

18. David Hoffman, "Bush Lays 'Slanderous' Leaks to Kerry; Senator Denies Charge; Contras and Drug-Running Involved," Washington Post, May 17, 1988.

19. Doyle McManus, "Senate Panel to Probe Iran-Contra Papers," Los Angeles Times, April 27, 1989.

20. Sara Fritz, "Hamilton Prods Bush on 2 Papers," Los Angeles Times, April 15, 1989.

21. "Dispute over Iran-Contra papers grows," Washington Post, in Sacramento Bee, April 27, 1989, which notes that incomplete versions of two of the six documents had reached the committee.

22. Doyle McManus, "Details Surface of U.S. Deal to Aid Contras," Los Angeles Times, April 16, 1989; "Iran-Contra Prober Doubts Bush's Denials," UPI, San Francisco Chronicle, May 8, 1989.

23. Select Committee on Intelligence, United States Senate, "Were Relevant Documents Withheld from the Congressional Committees Investigating the Iran-Contra Affair?" June 1989 (Doc. No. 199-533-89-1), p. 7.

24. Stephen Engelberg, " 'No Quid Pro Quo President Insists," New York Times, May 5, 1989.

25. Council on Hemispheric Affairs, "Bush, Gregg, Negroponte: Was There a Quid Pro Quo Deal?" Press release, May 16, 1989.

26. Government submission to U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia, April 6, 1989, Criminal No. 88-0080-02-GAG, pp. 31-2.

27. Gregg's testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, June 15, 1989.

28. Ibid.

29. Chosun Ilbo quoted by Peter Maass, "Gregg Post Causes Ire In Seoul; Envoy's CIA Past Resented by Critics," Washington Post, January 14, 1989.

30. Robert Parry, "Bush's Envoy on the Grill," Newsweek, May 29, 1989.

31. Robert Pear, "Bush Nominee Is Quizzed Over Illicit Contra Aid," New York Times, May 13, 1989.

32. Joseph Mianowany, "Former Bush aide tries to explain Iran-Contra role," UPI, May 13, 1989.

33. Emerson, op. cit., n. 15, pp. 124-26.

34. "'Black Hole,'" Newsweek, April 24, 1989.

35. Lee May, "Panel Probes Ex-Bush Aide on Contra Supply Scheme," Los Angeles Times, May 13, 1989.

36. Gregg's testimony before the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, June 15, 1989.

37. Joseph Pichirallo and Walter Pincus, "Gregg: Kept Bush in Dark About North Role; Senators Greet Ex-Aides' Contra Testimony with Skepticism," Washington Post, May 13, 1989.

38. Mary McGrory, "The Truth According to Gregg," Washington Post, June 22, 1989.

39. Walter Pincus, "State Dept. Budget, 4 Nominations Advance; Iran-Contra Questions Delayed 1 Appointee," Washington Post, June 9, 1989.

40. McGrory, op. cit., n. 38.