by Aksel Fridstrøm

Translated from Norwegian by Kathrine Jebsen Moore

July 2, 2020 - 19:10 SIST OPPDATERT Søndag 19. juli 2020 - 09:56

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

“I understand that this is controversial, but the public has a legitimate need to know, and it is important that it is possible to freely discuss alternate hypotheses on how the virus originated” Birger Sørensen starts to explain when Minerva visits him in his office one morning in Oslo.

Despite the explosiveness of his statements and research, Sørensen remains calm and collected.

Sørensen has been a point of controversy ever since former MI6 director Richard Dearlove cited a yet to be published article by Sørensen and his colleagues in an interview with The Daily Telegraph. The article claims that the virus that causes Covid-19 most likely has not emerged naturally.

“It’s a shame that there has already been so much talk about this, because I have yet to publish the article where I put forward my analysis”, Sørensen says in the form of an exasperated sigh.

Together with his colleagues, Angus Dalgleish and Andres Susrud have authored an article that looks into the most plausible explanations regarding the origins of the novel coronavirus. The article builds upon an already published article in the Quarterly Review of Biophysics that describes newly discovered properties in the virus spike protein. The authors are still in dialogue with scientific journals regarding an upcoming publication of the article.

News outlets are thus confronted with a difficult question: Are the findings and arguments Sørensen and his colleagues put forward of a sufficiently high quality to be presented and discussed in the public sphere? Sørensen explains that they in their dialogue with scientific journals are encountering a certain reluctance to publishing the article – without, however, proper scientific objections. Minerva has read a draft of the article, and has after an overall assessment decided that the findings and arguments do deserve public debate, and that this discussion cannot depend entirely on the publication process of scientific journals.

In this interview with Minerva, Sørensen therefore puts forward his hypothesis on why it is highly unlikely that the coronavirus emerged naturally.

On May 18th, WHO decided to conduct an inquiry into the coronavirus epidemic in China. Sørensen believes that it is important that this inquiry looks into new and alternate explanations for how the virus originated, beyond the already well-known suggestion that the virus originated in the Wuhan Seafood Market.

“There are very few who still believe that the epidemic started there, so as of today we have no good answers on how the epidemic started. Then we must also dare to look at more controversial, alternative explanations for the origin,” Sørensen says.

Birger Sørensen and one of his co-authors, Angus Dalgleish, are already known as HIV researchers par excellence.

In 2008, Sørensen’s work came to international attention when he launched a new immunotherapy for HIV. Angus Dalgleish is the professor at St. George’s Medical School in London who became world famous in 1984 after having discovered a novel receptor that the HIV virus uses to enter human cells.

The purpose of the work Sørensen and his colleagues have done on the novel coronavirus, has been to produce a vaccine. And they have taken their experience in trialling HIV vaccines with them to analyse the coronavirus more thoroughly, in order to make a vaccine that can protect against Covid-19 without major side effects.

Exceptionally well adjusted

“The difference between our approach and other vaccine manufacturers is that we have a chemistry background, and we analyse the virus in detail as if we were making a drug,” Sørensen starts to explain.

“Biology is also chemistry, so by considering the virus from a chemistry perspective, we carry out more detailed analysis, zooming in on certain components.”

Sørensen takes us through the basic elements of their approach:

“The first thing you need to establish is which parts of the virus are changing, and which parts are stable. If you want to make a vaccine that lasts, you must stimulate the immune system to react against those parts of the virus that are constant, otherwise the effect will disappear and, in the worst-case scenario, lead to increased illness.

“Once we know this, we can try to make a vaccine. Where we differ is that we are trying to make a vaccine that uses elements that have as little in common with the body’s natural components as possible, so that the immune system is taught to recognise exactly what the vaccine should protect against”, Sørensen elaborates.

Sørensen believes this is an important insight which will prevent the immune system from being falsely stimulated in a way that could lead the vaccine to create too many dangerous side effects in the vaccinated person.

“When we have not succeeded in creating an HIV vaccine, despite the enormous efforts put into that endeavour for the past 30 years, it is because we haven’t understood this,” Sørensen continues.

He believes that there has not been enough interaction between the part of the pharmaceutical industry that makes HIV medicines and the part that runs the vaccine research. As a consequence, the knowledge you need to make a successful vaccine against HIV in the big pharmaceutical companies has not been adequately exploited by the big, international HIV preventing vaccine studies that have been carried out.”

Asked about what significance his approached has had when he has analyzed the coronavirus, Sørensen explains:

“We have examined which components of the virus are especially well suited to attach themselves to cells in humans. And we have done this by comparing the properties of the virus with human genetics. What we found was that this virus was exceptionally well adjusted to infect humans.”

He pauses for a second.

“So well that it was suspicious,” he adds.

Perfected to infect humans

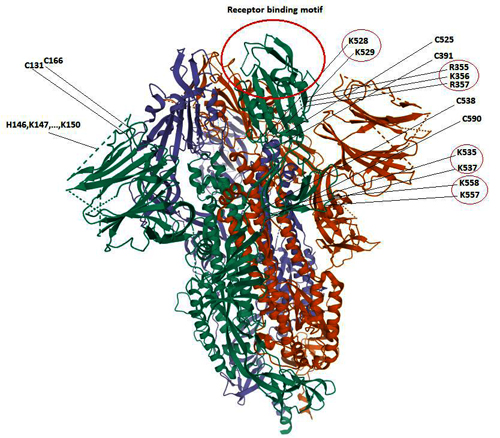

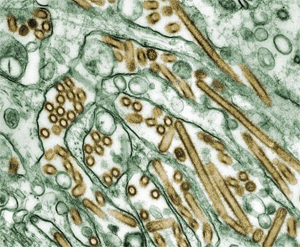

It is already known that the novel coronavirus, like the virus that caused the SARS epidemic in Southeast Asia in 2002-2003, could attach itself to the ACE-2 receptors in the lower respiratory tract.

“But what we have discovered is that there are properties in this new virus which enables it to use an additional receptor, and create a binding to human cells in the upper respiratory tract and the intestines which is strong enough to produce an infection,” Sørensen elaborates.

Sørensen says that it is the use of this additional receptor that most likely results in a different illness in Covid-19 patients than the one resulting from SARS.

“This is what enables the virus to transmit to a greater degree between humans, without the virus having attached itself to the ACE-2 receptors in the lower respiratory tract, where it causes deep pneumonia.

“That is also why so many of the Covid-19 patients have mild symptoms at the start of the illness, and are contagious before they develop severe symptoms,” he adds.

It might also explain why some people are ‘super spreaders’ without being ill themselves, Sørensen says.

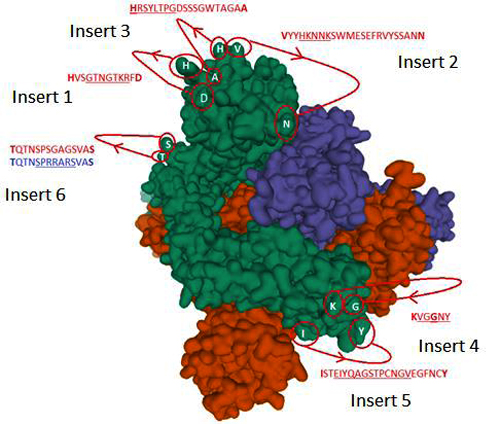

In the already published article Sørensen and his colleagues Angus Dalgleish and Andres Susrud describe what they claim is curious about the spike protein of the coronavirus, which makes it especially well suited to infect humans. These findings are the foundation for the hypothesis Sørensen and his colleagues develop in the new article, where they claim that the virus is not natural in origin.

“There are several factors that point towards this,” says Sørensen. “Firstly, this part of the virus is very stable; it mutates very little. That points to this virus as a fully developed, almost perfected virus for infecting humans.

“Secondly, this indicates that the structure of the virus cannot have evolved naturally. When we compare the novel coronavirus with the one that caused SARS, we see that there are altogether six inserts in this virus that stand out compared to other known SARS viruses,” he goes on explaining.

Sørensen says that several of these changes in the virus are unique, and that they do not exist in other known SARS coronaviruses.

“Four of these six changes have the property that they are suited to infect humans. This kind of aggregation of a type of property can be done simply in a laboratory, and helps to substantiate such an origin,” Sørensen points out.

FACT BOX – Spike Protein

A spike protein is a part of the virus attached to the surface of the virus. The spike protein is used by the virus when it enters cells, enabling it to stick in humans. The properties of the spike determines which receptors a virus can utilise and thus which cells the virus can enter to create illness.

An artificially created virus

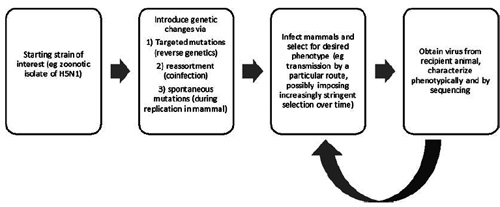

Asked about whether this implies that the virus is not natural, Sørensen goes on to explain the laboratory process that leads to the creation of new viruses.

“In a sense it is natural. But the natural processes have most likely been accelerated in a laboratory,” he explains. “It’s also possible for a virus to attain these properties in nature, but it’s not likely. If the mutations had happened in nature, we would have most likely seen that the virus had attracted other properties through mutations, not just properties that help the virus to attach itself to human cells.”

Sørensen vividly explains this argument:

“Imagine that you have cultivated a billion coronaviruses you have gathered from nature, then you take this mass of viruses and inject them into a human cell culture from for example the upper respiratory tract. As a result, a few of these viruses will change in order to better attach themselves to this type of cell in the nose and throat region and therefore to infect humans more easily. You end up with a virus with a spike protein which is perfect for attaching to and penetrating human cells.” Sørensen explains.

Asked about the particular mutations in the virus that lead to this conclusion, Sørensens says:

“What we see is that an area that you could observe in the first SARS coronavirus has been moved, so that the parts of the virus that are particularly well suited to attach to humans, have become part of the spike protein that the virus uses to penetrate human cells. And it is this moving of the area of the virus which makes the virus, together with the injected areas explained above, able to utilise an additional receptor to infect humans.”

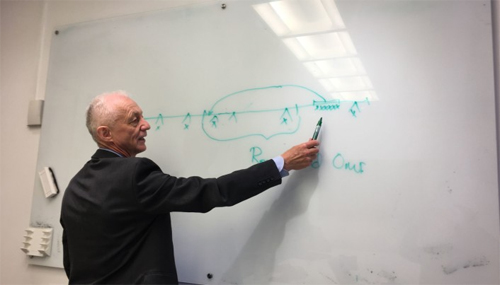

Sørensen explains at the black board. Photo: Aksel Fridstrøm

On a board in the meeting room where Sørensen is hosting our meeting, he illustrates what he is trying to explain, and how a component of the virus which previously was situated on another part of the shell of the virus, now has become a part of the spike protein of the virus.

More than ninety percent confident

Sørensen is therefore quite confident that the virus has originated in a laboratory.

“I think it’s more than 90 percent certain. It’s at least a far more probable explanation than it having developed this way in nature”, Sørensen responds.

Sørensen also highlights other data than those related to the virus’ properties:

“The properties that we now see in the virus, we have yet to discover anywhere in nature. We know that these properties make the virus very infectious, so if it came from nature, there should also be many animals infected with this, but we have still not been able to trace the virus in nature.

“The only place we are aware of where an equivalent virus to that which causes Covid-19 exists, is in a laboratory. So the simplest and most logical explanation is that it comes from a laboratory. Those who claim otherwise, have the burden of proof,” Sørensen says.

Critical voices suppressed

There are indeed earlier known experiments where changes to the corona virus have been engineered. An interesting example of this kind of research is a collaborative effort between Wuhan Institute of Virology and University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. In a 2015 article, Menachery et al. describe experiments with laboratory created corona viruses -– so called gain-of-function-studies. The purpose of this research is partly to be better prepared for new pathogenic variants of the virus. But the researchers also write: "the potential to prepare for and mitigate future outbreaks must be weighed against the risk of creating more dangerous pathogens". This risk must also be evaluated in light of previous known accidents where corona viruses have escaped from laboratories in China.

Fact box: Gain-of-function studies

According to US Department health & human services, gain-of-function studies refer to research which aims to increase the ability of a pathogen to cause disease. The method is controversial, because it entails risks, such as viruses escaping from labs. Between 2014 and 2018, this kind of research was prohibited in the United States, but in December 2017, American authorities announced that the ban would be lifted.

But several researchers have already pointed out that artificially created viruses would be easy to identify. We therefore ask Sørensen why this has not been identified earlier.

Sørensen believes there are several reasons for this.

“The first is that this is a very uncomfortable finding, and the production of new scientific articles that can be used to prove such findings has all but ground to a halt. Chinese scientists no longer publish articles that can be used to support such a hypothesis”, he says.

“And newer articles that are published about the virus must be thoroughly investigated, especially in relation to the basic material that is being used,” Sørensen expands, and points to a new x-ray article published in Nature by Shang et al., which Sørensen also earlier has criticised for being misleading.

“To do my analysis, I have therefore had to go back to the source material, and look at those articles that were published before the Covid-19 outbreak, where we have chosen to assume that the data that have been used is okay and reflects the actual conditions,” Sørensen says.

Asked about why there has not been more debate on this topic Sørensen has several explanations.

“This quickly becomes a discussion on politics, rather than science, Sørensen responds.

“Nobody wants to put forward the inconvenient truth, many scientists are also concerned about their own funding and position if they were to put forward such a controversial hypothesis. It is nevertheless a fact that many people on the web have engaged in such a debate. But so far, those who participate in such forums are characterized as conspiratorial. It is also the case that a debate about this type of viral research and the technologies used may damage reputation and lead to new restrictions on how to conduct molecular genetic research. With this in mind, it is not difficult to see that it must be difficult to get accepted papers in peer reviewed journals that focus on such research", Sørensen elaborates.

The fight for a controversial article

Birger Sørensen and Angus Dalgleish failed to get an article about the origins of the coronavirus published in a scientific journal. The authors suspect foul play and political considerations. Not everything gets published, is the answer from the journals. Minerva has obtained a draft of the paper, to let readers and researchers decide.

Hopes his arguments will be discussed properly

Sørensens himself is Chairman of the board at Immunor, a company which is working to develop their own vaccine candidate for Covid-19. Minerva has challenged him to address allegations that this hypothesis is launched publicly to attract funding for his own research.

“Of course, it’s in my interest that my research becomes known, but I am being completely open and have declared all my interests.

“At the same time, I argue that it must be possible for those of us who work for smaller biotechnology companies to present our findings and get them discussed properly. If anyone wishes to contest my findings, they are of course welcome to do so, but I hope they will engage thoroughly with the arguments rather than derail them by discussing my motives,” Sørensen responds.

*****************************

The fight for a controversial article: Birger Sørensen and Angus Dalgleish failed to get an article about the origins of the coronavirus published in a scientific journal. The authors suspect foul play and political considerations. Not everything gets published, is the answer from the journals. Minerva has obtained a draft of the paper, to let readers and researchers decide.

by Aksel Fridstrøm

July 13 2020 - 16:45 SIST OPPDATERT Mandag 13. juli 2020 - 20:10

In an interview with Minerva last week, the well-known Norwegian vaccine researcher and physical chemist Birger Sørensen argued that the novel coronavirus is not natural in origin.

Together with his colleagues Angus Dalgleish and Andres Susrud -– the latter in a data analytical role as statistician and data miner –- Sørensen has written a series of journal articles that put forward arguments for why the most likely explanation for the origin of the coronavirus is a laboratory.

If such findings were confirmed, there could be political ramifications. Naturally, therefore, Sørensen, Dalgleish and their unpublished paper have been mired in controversy ever since Sir Richard Dearlove, former head of the MI6, endorsed their conclusions. The authors themselves suspect that the controversial conclusions and the heated debate may have made journals reluctant to evaluate their paper objectively. However, tons of scientific articles are rejected for any number of reasons.

By tracing the writing of articles, the contact between the authors and the journals, and reviewing the findings, this article aims to shed light on a troubling question for the scientific community during the Corona crisis: One the one hand, there is an overabundance of papers and findings of highly variable quality -– some of which fuel conspiracy theories. On the other hand, the question of the origin of the Corona virus has become a fraught political question, with the Chinese government clamping down on independent research, and president Donald Trump claiming that the virus originated in a Chinese lab without producing any evidence to back up the assertion.

With the consent of Mr. Sørensen and his co-authors (henceforth: Sørensen and Dalgleish), Minerva has obtained a full print of the article, to be read freely by our readers – and by scientists, who may then discuss and dissect the paper.

Searching for a vaccine

It started out with something less controversial: Originally, the authors were engaged in analysis of the virus with the aim to create a vaccine. The discoveries that the authors claim to be relevant for determining the origin of the virus came as a by-product of this research.

In fact, Sørensen and Dalgleish have managed to get a paper on the corona virus peer reviewed and published, in Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics Discovery. This article, which is more closely linked to their vaccine development, deals with observations of the virus and the receptors that the virus can attach to in humans. Sørensen and Dalgleish do indeed believe that these properties indicate a lab origin for the virus. However, the article itself avoids any mention of this implication of the discovered properties.

Originally, the findings which are now published in Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics Discovery were part of a more condensed article, which included the lab origin hypothesis. To make this argument, the three have now instead written a second article, “The Evidence which Suggests that This Is No Naturally Evolved Virus”, that puts forward their arguments on why they believe the virus is likely to be a laboratory construct, by combining insights from the first paper with what is known from lab work on corona viruses.

However, this second article is yet to be accepted by a scientific journal -– having been rejected at different times and formats by three leading journals. Sørensen states that he is presently in dialogue with other journals regarding publication. A third paper on a related topic also taken from the original argument, is yet to be submitted.

Endorsed and criticized

Before we move on, let’s take a look on some of the reactions from within the scientific community. Sørensen has received both severe criticism and partial support.

Professor Kristian Andersen at the department of immunology and microbiology at Scripps Research, a medical research facility in California, was lead author on the article “The proximal origin of SARS-CoV-2” where he states that his “analyses clearly show that SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus”.

Andersen last week told Sky news that Sørensen’s and Dalgleish’s work was “complete nonsense, unintelligible, and not even remotely scientific – leading the authors to make unfounded and unsupported conclusions about the origin of SARS-CoV-2”. However, Andersen has not had an opportunity to read the second, unpublished article.

The principal reason for media dismissals of the lab origin possibility is a review paper in Nature Medicine (Andersen et al., 2020). Although by Jun 29, 2020 this review had almost 700 citations it also has major scientific shortcomings. These flaws are worth understanding in their own right but they are also useful background for understanding the implications of the Master’s thesis.

Andersen et al., a critique

The question of the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic is, in outline, simple. There are two incontrovertible facts. One, the disease is caused by a human viral pathogen, SARS-CoV-2, first identified in Wuhan in December 2019 and whose RNA genome sequence is known. Second, all of its nearest known relatives come from bats. Beyond any reasonable doubt SARS-CoV-2 evolved from an ancestral bat virus. The task the Nature Medicine authors set for themselves was to establish the relative merits of each of the various possible routes (lab vs natural) by which a bat coronavirus might have jumped to humans and in the same process have acquired an unusual furin site and a spike protein having very high affinity for the human ACE2 receptor.

When Andersen et al. outline a natural zoonotic pathway they speculate extensively about how the leap might have occurred. In particular they elaborate on a proposed residence in intermediate animals, likely pangolins. For example, “The presence in pangolins of an RBD [Receptor Binding Domain] very similar to that of SARS-CoV-2 means that we can infer that this was probably in the virus that jumped to humans. This leaves the insertion of [a] polybasic cleavage site to occur during human-to-human transmission.” This viral evolution occurred in “Malayan pangolins illegally imported into Guangdong province”. Even with these speculations there are major gaps in this theory. For example, why is the virus so well adapted to humans? Why Wuhan, which is 1,000 Km from Guangdong? (See map).

The authors provide no such speculations in favour of the lab accident thesis, only speculation against it:

“Finally, the generation of the predicted O-linked glycans is also unlikely to have occurred due to cell-culture passage, as such features suggest the involvement of an immune system.” (italics added).

[Passaging is the deliberate placing of live viruses into cells or organisms to which they are NOT adapted for the purpose of making them adapted, i.e. speeding up their evolution.]

It is also noteworthy that the Andersen authors set a higher hurdle for the lab thesis than the zoonotic thesis. In their account, the lab thesis is required to explain all of the evolution of SARS-CoV-2 from its presumed bat viral ancestor, whereas under their telling of the zoonotic thesis the key step of the addition of the furin site is allowed to happen in humans and is thus effectively unexplained.

A further imbalance is that key information needed to judge the merits of a lab origin theory is missing from their account. As we detailed in our previous article, in their search for SARS-like viruses with zoonotic spillover potential, researchers at the WIV have passaged live bat viruses in monkey and human cells (Wang et al., 2019). They have also performed many recombinant experiments with diverse bat coronaviruses (Ge et al., 2013; Menachery et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2017). Such experiments have generated international concern over the possible creation of potential pandemic viruses (Lipsitch, 2018). As we showed too, the Shi lab had also won a grant to extend that work to whole live animals. They planned “virus infection experiments across a range of cell cultures from different species and humanized mice” with recombinant bat coronaviruses. Yet Andersen et al did not discuss this research at all, except to say:

“Basic research involving passage of bat SARS-CoV-like coronaviruses in cell culture and/or animal models has been ongoing for many years in biosafety level 2 laboratories across the world”

This statement is fundamentally misleading about the kind of research performed at the Shi lab.

A further important oversight by the Andersen authors concerns the history of lab outbreaks of viral pathogens. They write: “there are documented instances of laboratory escapes of SARS-CoV”. This is a rather matter-of-fact allusion to the fact that since 2003 there have been six documented outbreaks of SARS from labs, not all in China, with some leading to fatalities (Furmanski, 2014).

Andersen et al might have also have noted that two major human pandemics are widely accepted to have been caused by lab outbreaks of viral pathogens, H1N1 in 1977 and Venezuelan Equine Encephalitis (summarised in Furmanski, 2014). Andersen could even have noted that literally hundreds of lab accidents with viruses have resulted in near-misses or very localised outbreaks (summarised by Lynn Klotz and Sam Husseini and also Weiss et al., 2015).

Also unmentioned were instances where a lab outbreak of an experimental or engineered virus has been plausibly theorised but remains uninvestigated. For example, the most coherent explanation for the H1N1 variant ‘swine flu’ pandemic of 2009/10 that resulted in a death toll estimated by some as high as 200,000 (Duggal et al., 2016; Simonsen et al. 2013), is that a vaccine was improperly inactivated by its maker (Gibbs et al., 2009). If so, H1N1 emerged from a lab not once but twice.

Given that human and livestock viral outbreaks have frequently come from laboratories and that many scientists have warned of probable lab escapes (Lipsitch and Galvani, 2014), and that the WIV [Wuhan Institute of Virology] itself has a questionable biosafety record, the Andersen paper is not an even-handed treatment of the possible origins of the COVID-19 virus.

Yet its text expresses some strong opinions: “Our analyses clearly show that SARS-CoV-2 is not a laboratory construct or a purposefully manipulated virus….It is improbable that SARS-CoV-2 emerged through laboratory manipulation of a related SARS-CoV-like coronavirus…..the genetic data irrefutably show that SARS-CoV-2 is not derived from any previously used backbone….the evidence shows that SARS-CoV2 is not a purposefully manipulated virus….we do not believe that any type of laboratory-based scenario is possible.” (Andersen et al., 2020).

It is hard not to conclude that what their paper mostly shows is that Drs. Andersen, Rambaut, Lipkin, Holmes and Garry much prefer the natural zoonotic transfer thesis. Their rhetoric is forthright but the evidence does not support that confidence.

Indeed, since the publication of Andersen et al., important new evidence has emerged that undermines their zoonotic origin theory. On May 26th the Chinese CDC ruled out the Huanan “wet” market in Wuhan as the source of the outbreak. Additionally, new research on pangolins, the favoured intermediate mammal host, suggests they are not a natural reservoir of coronaviruses (Lee et al., 2020; Chan and Zhan, 2020). Furthermore, SARS-CoV-2 was found not to replicate in bat kidney or lung cells (Rhinolophus sinicus), implying that SARS-CoV-2 is not a recently-adapted spill over Chu et al., 2020)...

The final point that we would like to make is that the principal zoonotic origin thesis is the one proposed by Andersen et al. Apart from being poorly supported this thesis is very complex. It requires two species jumps, at least two recombination events between quite distantly related coronaviruses and the physical transfer of a pangolin (having a coronavirus infection) from outside China (Andersen et al., 2020). Even then it provides no logical explanation of the adaptedness of SARS-CoV-2 across its whole genome or why the virus emerged in Wuhan.

-- A Proposed Origin for SARS-CoV-2 and the COVID-19 Pandemic, by Jonathan Latham, PhD and Allison Wilson, PhD

Minerva has, however, shared that second article with Birgitta Åsjö, a professor emerita in virology at the university of Bergen. She is puzzled by Andersen’s comments, and rejects the notion that Sørensen’s and Dalgleish’ work is unscientific nonsense. “Andersen is harsh, I don’t know why he’s so harsh. I don’t want to dismiss it completely”, she told Minerva in an interview.

Åsjö does not consider the article to contain conclusive evidence that the novel coronavirus has a lab origin, but adds that she considers the article to contain “interesting findings”. She is herself critical of some of the arguments presented in Andersen’s own article on the origin of the virus.

In particular, Åsjö is interested in Sørensen’s and Dalgleish’ findings concerning properties of a swine corona virus detected in connection with an outbreak among piglets in Guandong in 2016–2017, and its possible significance for the present SARS-CoV-2 virus. So far, the controversy seems to resemble other controversies between academics who rarely hesitate to describe rivalling theories in the harshest possible terms. Indeed, Sørensen and Dalgleish originally intended to publish their arguments as a stark critique of the article by Andersen et al in Nature and what they describe “as puzzling errors in their use of evidence”.

Self-confident scientists and strict journals

With this aim, Angus Dalgleish wrote a letter to the editor in Nature on April 2, requesting that journal to publish an earlier version of these arguments.

This article was rejected by Nature five days later, on April 7. Announcing the rejection, João Monteiro, chief editor in Nature Medicine, wrote to Dalgleish:

First rejection from Nature Medicine

“While we appreciate that the points you have raised extend the discussion about the origin of SARS-CoV2 further our opinion is that the content complements other viewpoints that have been considered and published elsewhere, and therefore would be as appropriate for publication in the specialized literature. Please note that this is not a criticism regarding the importance of the matter or the quality of your analyses, but rather an editorial assessment of priority for publication, in a time when there are many pressing issues of public health and clinical interest that take precedence for publication in Nature Medicine, and limited space in the journal.”

Monteiro ended the email by encouraging Dalgleish to post his comments in one of “the accepted preprint repositories so that it remains visible and adds to the discussion about the origin of the virus.”

A clearly angered Dalgleish then wrote a response stating: “Thank you for your extraordinarily unhelpful replies. We can only conclude that the Nature editorial team does not understand that there is no scientific issue in the world at present more important than establishing with scientific precision the aetiology of the Covid-19 virus.”

After the first rejection by Nature, the authors approached another premier journal, Journal of Virology. However, by April 20, the first version of the paper had been rejected there as well. A few days later, this version of the paper was put to death by a rejection from bioRxiv, a non-peer-reviewed preprint repository. The stated reason for rejection was that the format of the paper did not conform to a normal, full research paper, with sections such as "Methods" and "Results".

The first iteration of rejections thus seem to fit into a typical pattern: Scientists with overconfidence not only in the quality of their own research, but also its relevance and significance, encountering journals with strict guidelines for format, each with its own mission and focus, and not very patient with professors that flaunt formal requirements.

Still, it seems that the actual arguments put forward might not have been properly evaluated, or could not be properly evaluated in this setting. And the findings, if correct, would seem to merit some sort of scientific attention. How to proceed?

A publication and new rejections

After the initial round of rejections, the authors made several revisions to their original article, with the arguments sectioned into separate articles. The first article –- an analysis of the novel coronavirus, for the purpose of vaccine design, without making the argument that the virus is engineered –- was published June 2 in the Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics Discovery which is one of the top peer-reviewed science journals in the world.

Having achieved this publication, and presumably regained confidence that the scientific quality of the work was all right, Sørensen and Dalgleish again reached out to several of the world’s most prestigious scientific journals. Now they wanted to publish the second article, which builds on the first, already accepted article, and presents their arguments for why the coronavirus is of a non-natural origin.

However this article was again rejected by Nature on June 24 – without being sent out to peer review. The rejection, written by Senior Editor Clare Thomas, states:

Second rejection from Nature Medicine

It is our policy to decline a substantial proportion of manuscripts without sending them to referees so that they may be sent elsewhere without further delay. In making this decision, we are not questioning the technical quality or validity of your findings, or their value to others working in this area, only assessing the suitability of the study based on the editorial criteria of the journal. In this case, we do not believe that the work represents a development of sufficient scientific impact such that it might merit publication in Nature. We therefore feel that the study would find a more suitable audience in another journal.

On July 1, Sørensen and his colleagues therefore challenged Science, another scientific journal to publish his article. Arguing for the publication of the article Sørensen wrote in an e-mail to editor Professor Holden Thorp:

“Now that Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus has indicated that WHO will pursue a long-overdue inquiry into the aetiology of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, which we welcome, we hope that you will support the very necessary debate that is now breaking in a second wave, following the publication of our vaccine. We are aware of significant responsible mainstream media interventions that are imminent. We are glad that this important question will now be addressed where it should be, in mainstream media and science journals, and not left to internet speculations, some of which have been both uninformed and therefore unhelpful, in our view.”

However, Sørensen was rebuffed also by Science the very next day. In an email to Sørensen, Professor Throp wrote that the article was unfit for publishing in Science, due to the fact that it criticizes work published in another journal.

Rejection from Science

Dr. Sorenson,

Thank you for your interest. We do not publish papers that are critiques of works in other journals, so we cannot consider something along these lines.

Holden

Holden Thorp

Editor-in-Chief

On the rejections from the scientific journals co-author Angus Dalgleish told Sky News: “I thought the whole point of a scientific journal was that you put forward some speculation and you opened it up to debate”, said Professor Dalgleish.

Agree or disagree with Dalgleish’s description of what a scientific journal does, the new round of rejections complicate the picture from the first round. A major part of the argument was accepted by a respectable journal -– the one that didn’t spell out the implications for the origin of the virus. The article that did spell it out, was now rejected twice, without peer review, and the second rejection on purely formal grounds that the authors vehemently contest, arguing that the paper in its current form is not first and foremost a critique of the Andersen et al. paper.

Minerva has asked both Nature and Science to elaborate on the reasons for why the articles by Sørensen and his co-authors have been rejected. Both Science and Nature have declined to comment on the specific rejection of the article as they view this information as confidential. However, Executive Director of the Science Press Package Meagan Phelan, replied that “Science receives upwards of 11,000 manuscripts per year, and the acceptance rate is 6%, so the vast majority of papers are rejected for one reason or another. Science’s acceptance rate for COVID-19-related submissions is even lower, at 4%. The journal continues to receive an exceptionally high volume of COVID-19-related submissions each week.”

At press time, the second article is still in search of a scientific journal willing to publish – or, at least, to subject it to peer review.

Correction: The name Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics has been changed to Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics Discovery