Part 2 of 2

Second, there is an article in the Mother Jones [“The Non-paranoid Person’s Guide to Viruses Escaping from Labs”] on the virus situation. And in the article, by Rowan Jacobsen, J-A-C-O-B-S-E-N, it says, and I'm quoting,

"It's doubtful we'll ever pinpoint COVID-19's origins. Despite many experts' skepticism, no one I talked to said they could confidently rule out the possibility that it accidentally escaped from a lab that was studying it. But it also could have been carried to Wuhan by someone who was infected elsewhere, or by an animal that served as an intermediate host. Yet it may turn out for the best that the Wuhan lab is now in the news. Most people don't realize how heroic some of its work was or how it could have helped to head off the next pandemic." In all the discussions of the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic, enormous scientific attention has been paid to the molecular character of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, including its novel genome sequence in comparison with its near relatives. In stark contrast, virtually no attention has been paid to the physical provenance of those nearest genetic relatives, its presumptive ancestors, which are two viral sequences named BtCoV/4991 and RaTG13.

This neglect is surprising because their provenance is more than interesting. BtCoV/4991 and RaTG13 were collected from a mineshaft in Yunnan province, China, in 2012/2013 by researchers from the lab of Zheng-li Shi at the Wuhan Institute of Virology (WIV). Very shortly before, in the spring of 2012, six miners working in the mine had contracted a mysterious illness and three of them had died (Wu et al., 2014). The specifics of this mystery disease have been virtually forgotten; however, they are described in a Chinese Master’s thesis written in 2013 by a doctor who supervised their treatment.

We arranged to have this Master’s thesis translated into English. The evidence it contains has led us to reconsider everything we thought we knew about the origins of the COVID-19 pandemic. It has also led us to theorise a plausible route by which an apparently isolated disease outbreak in a mine in 2012 led to a global pandemic in 2019...

We do not propose a specifically genetically engineered or biowarfare origin for the virus but the theory does propose an essential causative role in the pandemic for scientific research carried out by the laboratory of Zheng-li Shi at the WIV; thus also explaining Wuhan as the location of the epicentre.

Why has the provenance of RaTG13 and BtCoV/4991 been ignored?

The apparent origin of the COVID-19 pandemic is the city of Wuhan in Hubei province, China. Wuhan is also home to the world’s leading research centre for bat coronaviruses. There are two virology labs in the city, both have either collected bat coronaviruses or researched them in the recent past. The Shi lab, which collected BtCoV/4991 and RaTG13, recently received grants to evaluate by experiment the potential for pandemic pathogenicity of the novel bat coronaviruses they collected from the wild.

To add to these suggestive data points, there is a long history of accidents, disease outbreaks, and even pandemics resulting from lab accidents with viruses (

Furmanski, 2014; Weiss et al., 2015)....

As we detailed in our previous article, in their search for SARS-like viruses with zoonotic spillover potential, researchers at the WIV have passaged live bat viruses in monkey and human cells (Wang et al., 2019). They have also performed many recombinant experiments with diverse bat coronaviruses (Ge et al., 2013; Menachery et al., 2015; Hu et al., 2017). Such experiments have generated international concern over the possible creation of potential pandemic viruses (Lipsitch, 2018). As we showed too, the Shi lab had also won a grant to extend that work to whole live animals. They planned “virus infection experiments across a range of cell cultures from different species and humanized mice” with recombinant bat coronaviruses. Yet Andersen et al did not discuss this research at all, except to say:

“Basic research involving passage of bat SARS-CoV-like coronaviruses in cell culture and/or animal models has been ongoing for many years in biosafety level 2 laboratories across the world”

This statement is fundamentally misleading about the kind of research performed at the Shi lab....

BtCoV/4991 was first described in 2016. It is a 370 nucleotide virus fragment collected from the Mojiang mine in 2013 by the lab of Zeng-li Shi at the WIV [Wuhan Institute of Virology] (Ge et al., 2016). BtCoV/4991 is 100% identical in sequence to one segment of RaTG13. RaTG13 is a complete viral genome sequence (almost 30,000 nucleotides) that was only published in 2020, after the pandemic began (P. Zhou et al., 2020).

Despite the confusion created by their different names, in a letter obtained by us Zheng-li Shi confirmed to a virology database that BtCoV/4991 and RaTG13 are both from the same bat faecal sample and the same mine. They are thus sequences from the same virus. In the discussion below we will refer primarily to RaTG13 and specify BtCoV/4991 only as necessary.

These specifics are important because it is these samples and their provenance that we believe are ultimately key to unravelling the mystery of the origins of COVID-19.

The story begins in April 2012 when six workers in that same Mojiang mine fell ill from a mystery illness while removing bat faeces. Three of the six subsequently died.

In a March 2020 interview with Scientific American Zeng-li Shi dismissed the significance of these deaths, claiming the miners died of fungal infections. Indeed, no miners or deaths are mentioned in the paper published by the Shi lab documenting the collection of RaTG13 (Ge et al., 2016).

But Shi’s assessment does not tally with any other contemporaneous accounts of the miners and their illness (Rahalkar and Bahulikar, 2020). As these authors have pointed out, Science magazine wrote up part of the incident in 2014 as A New Killer Virus in China?. Science was citing a different team of virologists who found a paramyxovirus in rats from the mine. These virologists told Science they found “no direct relationship between human infection” and their virus. This expedition was later published as the discovery of a new virus called MojV after Mojiang, the locality of the mine (Wu et al., 2014).

What this episode suggests though is that these researchers were looking for a potentially lethal virus and not a lethal fungus. Also searching the Mojiang mine for a [potentially lethal] virus at around the same time was Canping Huang, the author of a PhD thesis carried out under the supervision of George Gao, the head of the Chinese CDC.

All of this begs the question of why the Shi lab, which has no interest in fungi but a great interest in SARS-like bat coronaviruses, also searched the Mojiang mine for bat viruses on four separate occasions between August 2012 and July 2013, even though the mine is a 1,000 Km from Wuhan (Ge et al., 2016). These collecting trips began while some of the miners were still hospitalised.

Fortunately, a detailed account of the miner’s diagnoses and treatments exists. It is found in a Master’s thesis written in Chinese in May 2013. Its suggestive English title is “The Analysis of 6 Patients with Severe Pneumonia Caused by Unknown viruses“.

The original English version of the abstract implicates a SARS-like coronavirus as the probable causative agent and that the mine “had a lot of bats and bats’ feces”...

The significance of the Master’s thesisThese findings of the thesis are significant in several ways.

First, in the light of the current coronavirus pandemic it is evident the miners’ symptoms very closely resemble those of COVID-19 (Huang et al, 2020; Tay et al., 2020; M. Zhou et al., 2020). Anyone presenting with them today would immediately be assumed to have COVID-19. Likewise, many of the treatments given to the miners have become standard for COVID-19 (Tay et al., 2020).

Second, the remote meeting with Zhong Nanshan is significant. It implies that the illnesses of the six miners were of high concern and, second, that a SARS-like coronavirus was considered a likely cause.

Third, the abstract, the conclusions, and the general inferences to be made from the Master’s thesis contradict Zheng-li Shi’s assertion that the miners died from a fungal infection. Fungal infection as a potential primary cause was raised but largely discarded.

Fourth, if a SARS-like coronavirus was the source of their illness the implication is that it could directly infect human cells. This would be unusual for a bat coronavirus (Ge et al., 2013). People do sometimes get ill from bat faeces but the standard explanation is histoplasmosis, a fungal infection and not a virus (McKinsey and McKinsey, 2011; Pan et al., 2013).

Fifth, the sampling by the Shi lab found that bat coronaviruses were unusually abundant in the mine (Ge at al., 2016). Among their findings were two betacoronaviruses, one of which was RaTG13 (then known as BtCoV/4991). In the coronavirus world betacoronaviruses are special in that both SARS and MERS, the most deadly of all coronaviruses, are both betacoronaviruses. Thus they are considered to have special pandemic potential, as the concluding sentence of the Shi lab publication which found RaTG13 implied: “special attention should particularly be paid to these lineages of coronaviruses” (Ge at al., 2016). In fact, the Shi and other labs have for years been predicting that bat betacoronaviruses like RaTG13 would go pandemic; so to find RaTG13 where the miners fell ill was a scenario in perfect alignment with their expectations....

it now seems that the Shi lab at the WIV did not forget about RaTG13 but were sequencing its genome in 2017 and 2018. However, we believe that the Master’s thesis indicates a much simpler explanation.

We suggest, first, that inside the miners RaTG13 (or a very similar virus) evolved into SARS-CoV-2, an unusually pathogenic coronavirus highly adapted to humans. Second, that the Shi lab used medical samples taken from the miners and sent to them by Kunming University Hospital for their research. It was this human-adapted virus, now known as SARS-CoV-2, that escaped from the WIV in 2019....

The Master’s thesis also states its regret that no samples for research were taken from patients 1 and 2, implying that samples were taken from all the others.

We further know that, on June 27th, 2012, the doctors performed an unexplained thymectomy on patient 4. The thymus is an immune organ that can potentially be removed without greatly harming the patient and it could have contained large quantities of virus. Beyond this the Master’s thesis is unfortunately unclear on the specifics of what sampling was done, for what purpose, and where each particular sample went.

Given the interests of the Shi lab in zoonotic origins of human disease, once such a sample was sent to them, it would have been obvious and straightforward for them to investigate how a virus from bats had managed to infect these miners. Any viruses recoverable from the miners would likely have been viewed by them as a unique natural experiment in human passaging offering unprecedented and otherwise-impossible-to-obtain insights into how bat coronaviruses can adapt to humans.

The logical course of such research would be to sequence viral RNA extracted directly from unfrozen tissue or blood samples and/or to generate live infectious clones for which it would be useful (if not imperative) to amplify the virus by placing it in human cell culture. Either technique could have led to accidental infection of a lab researcher.

Our supposition as to why there was a time lag between sample collection (in 2012/2013) and the COVID-19 outbreak is that the researchers were awaiting BSL-4 lab construction and certification, which was underway in 2013 but delayed until 2018.

We propose that, when frozen samples derived from the miners were eventually opened in the Wuhan lab they were already highly adapted to humans to an extent possibly not anticipated by the researchers. One small mistake or mechanical breakdown could have led directly to the first human infection in late 2019.

Thus, one of the miners, most likely patient 3, or patient 4 (whose thymus was removed), was effectively patient zero of the COVID-19 epidemic. In this scenario, COVID-19 is not an engineered virus; but, equally, if it had not been taken to Wuhan and no further molecular research had been performed or planned for it then the virus would have died out from natural causes, rather than escaped to initiate the COVID-19 pandemic....

Further questionsThe hypothesis that SARS-CoV-2 evolved in the Mojiang miner’s lungs potentially resolves many scientific questions about the origin of the pandemic. But it raises others having to do with why this information has not come to light hitherto. The most obvious of these concern the actions of the Shi lab at the WIV.

Why did the Shi lab not acknowledge the miners’ deaths in any paper describing samples taken from the mine (Ge et al., 2016 and P. Zhou et al., 2020)? Why in the title of the Ge at al. 2016 paper did the Shi lab call it an “abandoned” mine? When they published the sequence of RaTG13 in Feb. 2020, why did the Shi lab provide a new name (RaTG13) for BtCoV/4991 when they had by then cited BtCoV/4991 twice in publications and once in a genome sequence database and when their sequences were from the same sample and 100% identical (P. Zhou et al., 2020)? If it was just a name change, why no acknowledgement of this in their 2020 paper describing RaTG13 (Bengston, 2020)? These strange and unscientific actions have obscured the origins of the closest viral relatives of SARS-CoV-2, viruses that are suspected to have caused a COVID-like illness in 2012 and which may be key to understanding not just the origin of the COVID-19 pandemic but the future behaviour of SARS-CoV-2.

These are not the only questionable actions associated with the provenance of samples from the mine. There were five scientific publications that very early in the pandemic reported whole genome sequences for SARS-CoV-2 (Chan et al., 2020; Chen et al., 2020; Wu et al., 2020; P. Zhou et al., 2020; Zhu et al., 2020). Despite three of them having experienced viral evolutionary biologists as authors (George Gao, Zheng-li Shi and Edward Holmes) only one of these (Chen et al., 2020) succeeded in identifying the most closely related viral sequence by far: BtCoV/4991 a viral sequence in the possession of the Shi lab at the WIV that differed from SARS-CoV-2 by just 5 nucleotides.

-- A Proposed Origin for SARS-CoV-2 and the COVID-19 Pandemic, by Jonathan Latham, PhD and Allison Wilson, PhD

"They also haven't grasped the danger posed by the work being done at high-security biolabs around the world. Yet, the next pandemic could start from a lab in China. But it could just as easily come from our own backyard. In recent decades, more diseases have been jumping from animals to humans, a phenomenon called zoonotic spillover. Experts blame our increasing incursions into the natural world. As we convert forests to farms and hunt wild animals, we give viruses new opportunities for spillover." Now, Andrew, you are a lawyer and you're a litigator, correct?

Andrew Kimbrell: Yes.

Ralph Nader: Okay. So you know the difference between plausibility and probative evidence. Tell our listeners the difference.

Andrew Kimbrell: Well, I think that there is plausibility, but I would switch it to preponderance of the evidence. Quite often in civil trials you only have circumstantial evidence, and some scientific evidence, but you don't have sufficient evidence to say beyond a reasonable doubt. You have to say, "Listen, this is the cause, this did it, we got it, here's the gun, here's how it happened," but you have circumstantial evidence. So you have a preponderance of the ‘which is more likely.’ And that's all we can do right now with this is say, "Which is more likely? Is it more likely with this chimeric virus, that some bat met a pangolin in a bar in Wuhan and with a human, and somehow all that happened?" We know the wet market has been debunked. The Chinese government has debunked it; science has debunked it. So we got to get rid of these wet markets; they are horror shows; they're unethical; they hurt wildlife; we should all get together and close every wet market there is around there; it's terrible. But it didn't create COVID-19. No respectable scientist now says it did. The bat soup, bat bite theory is dead. And there is no other tangible theory. How did one animal get simultaneously infected by two or three other animals that had the unique capacity that COVID-19 has?

There's a very important article by Nikolai Petrovsky, one of the most highly respected vaccine scientists in the world, that came out in late May in Science Times. He and his team in Australia had done comprehensive surveys, looking at all the animals they could find, and there wasn't a single animal out there that could serve as the reservoir for this. And he said, this virus was exquisitely designed to be infective to humans, and completely unlike any virus they had known.

An extremely important but still unanswered question is what was the original source of the COVID-19 virus. While SARS-CoV-2 has some similarities to SARS CoV and other bat viruses, no natural virus matching to COVID-19 has yet been found in animals. Our group at Flinders University in collaboration with researchers at La Trobe University have used a modelling approach to study the possible evolutionary origins of COVID-19 by modelling interactions between its spike protein and a broad variety of ACE2 receptors from animals and humans. This work which has been made available on a prepress server, Arxiv and is downloadable at

http://arxiv.org/abs/2005.06199 shows that the strength of binding of COVID-19 to human ACE2 exceeds the predicted strength of binding to ACE2 of the other tested species, with pangolin ACE2 having the next highest affinity.

The devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic caused by SARS–coronavirus 2 (SARSCoV-2) has raised important questions on the origins of this virus, the mechanisms of any zoonotic transfer from exotic animals to humans, whether companion animals or those used for commercial purposes can act as reservoirs for infection, and the reasons for the large variations in SARS-CoV-2 susceptibilities across animal species. Traditional lab-based methods will ultimately answer many of these questions but take considerable time. Increasingly powerful in silico modeling methods provide the opportunity to rapidly generate information on newly emerged pathogens to aid countermeasure development and also to predict potential future behaviors. We used an in silico structural homology modeling approach to characterize the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein which predicted its high affinity binding to the human ACE2 receptor. Next we sought to gain insights into the possible origins and transmission path by which SARS-CoV-2 might have crossed to humans by constructing models of the ACE2 receptors of relevant species, and then calculating the binding energy of SARS-CoV-2 spike protein to each of these. Notably, SARS-CoV-2 spike protein had the highest overall binding energy for human ACE2, greater than all the other tested species including bat, the postulated source of the virus. This indicates that SARS-CoV-2 is a highly adapted human pathogen. Of the species studied, the next highest binding affinity after human was pangolin, which is most likely explained by a process of convergent evolution. Binding of SARS-CoV-2 for dog and cat ACE2 was similar to affinity for bat ACE2, all being lower than for human ACE2, and is consistent with only occasional observations of infections of these domestic animals. Snake ACE2 had low affinity for spike protein, making it highly improbable that snakes acted as an intermediate vector. Overall, the data indicates that SARS-CoV-2 is uniquely adapted to infect humans, raising important questions as to whether it arose in nature by a rare chance event or whether its origins might lie elsewhere.

-- In silico comparison of spike protein-ACE2 binding affinities across species; significance for the possible origin of the SARS-CoV-2 virus, by Sakshi Piplani, Puneet Kumar Singh, David A. Winkler, Nikolai Petrovsky

This high binding to human ACE2 suggests the possibility that the COVID-19 spike protein has previously undergone selection on human ACE2 or a closely related ACE2 variant. How this might have happened is currently unknown and warrants further scientific investigation.

-- Nikolai Petrovsky, Professor in the College of Medicine and Public Health at Flinders University and Research Director, Vaxine Pty Ltd in "The Case is Building That COVID-19 Had a Lab Origin, by Jonathan Latham, Ph.D. and Allison Wilson, Ph.D.

Ralph Nader: First of all, just to clarify for our listeners, you're saying there's a preponderance of the evidence that it accidentally was leaked from the lab. You're not saying deliberate, right?

Andrew Kimbrell: No. No. I don't think it was deliberately released. And by the way, for the folks out there, I really get it that we all need to be worried about biological weapons research. We know it's going on in China. We know it's still going on in the US, and almost certainly going on in Russia. So I don't want to give, anymore than I want to give the wet markets a pass, I don't want to give biological weapons research a pass. It's a huge danger, a bio-security danger to us as well. However, it is highly, probably unlikely that COVID-19 would ever be a bio weapon [because] it would boomerang. It's highly infectious in humans. It would boomerang on your own population. It would make no sense. So, yes, accidental release, not deliberate release, a product of genetic engineering that took a SARS-like virus and they wanted to see how transmissible they could make it; they wanted to see how lethal they could make it, and it escaped.Ralph Nader: I have to question your science, because I've heard on the radio and read in the media where there are scientists who say it came from animals. And the fact is there was a very respectable scientist in Wuhan who completely dismissed the leak from the lab, and said it was zoonotically or sourced in animal transmission. That doesn't mean that's the case, Andy. It just . . .

Andrew Kimbrell: Ralph, no. I said that the wet market hypothesis, the one you mentioned, the one that was popular in the media, has been completely debunked. They still say it could have been natural, some other animals could have done it, but there is no real scenario for that.

But here is what I want to point out. I don't want to get lost in this discussion, because this is where everyone gets lost, and it defeats the purpose of why I'm on your show today. I'm not concerned with proving one thing or the other. Shi Zhengli, who is the bat woman, who is director of the Wuhan Institute of Virology’s [Center for Emerging Infectious Diseases], said when she heard and saw the virus going out there, and she saw the pandemic, she didn't sleep a wink for days she was so afraid. This is her saying,

"I didn't sleep a wink for days." She said, "I was afraid that that virus had come from my lab."

So we don't need a lot of people saying what's possible. I said

Petrovsky, and you mentioned Lacey, and

Jonathan Latham has an excellent article on this. I recommend everyone read

the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists on June 4th with Milton Leitenberg's excellent and very well-researched analysis so you can make your own decision about whether you think it was lab or natural. The most important thing is that the woman who actually was the head of that gain of threat research, funded by the NIH for five years, said she was so afraid she couldn't sleep a wink, Ralph.

Ralph Nader: You say she couldn't sleep at night, but what is her position right now?

Andrew Kimbrell: Her position is she looked through all of her viruses, and she said this was not one of them. Now, of course, we don't have those records. And maybe she's right, and maybe she's wrong. But the point I'm trying to make here is that it could have happened. If this gain of research could have been a cause, there's a reasonable belief that it could have been a cause, and there are scientists across the board -- you mentioned several, and I mentioned several, including her -- who said that she was so afraid that her research had caused it, that she couldn't sleep. That's all I care about. That means that this research is admittedly something that could create the next pandemic. This gain of threat research could create new pandemic viruses. Fouchier is doing it in the Netherlands with NIH money. Kawaoka is doing it at the University of Wisconsin. And there are many, many other scientists, including Shi Zhengli in China, who are still doing it. That means they agree that this could be the source of a new pandemic that could be even worse than we're seeing now. That's the only answer we need.

Ralph Nader: What's the suggestion for further investigations? Where? Who?

Andrew Kimbrell: We don't need further investigation, unless you want to try and prove it one way or the other. And China probably will never release any records they have from that laboratory. And China has actively destroyed a huge amount of evidence that is in the public record. I'm saying what we need now is to say that research on vaccines is great, go for it; and viral research, go for it. Lots of research is really important. But we need to reinstate the 2014 Obama moratorium on this gain of threat research, potential pandemic viruses. It represents an existential threat to the human population. It's providing little or zero help in any vaccine.

And again, I rely on

Marc Lipsitch, and

Tom Inglesby and Richard Ebright, the top scientists in the field who have said exactly what I'm saying.

And Marc Lipsitch, at Harvard, epidemiology specialist at Harvard, has said that for every year that they work on one of these pandemic viruses with this gain of threat, engineering animal research, there's a 1 in 1000 chance of an accidental escape from the lab. This has not been part of the public debate. We've debated nuclear weapons; we've debated other GMOs; but we have not said we need a moratorium, a multi-year moratorium, hopefully a ban, on genetically engineering these potential pandemic viruses, when they're providing us almost no medical benefit. So that's the key that we need to focus on rather than back and forth, or using it as anti-China or Trump. That's the hidden forest that we need to look at, and not get so obsessed with the trees.

Ralph Nader: Fair enough, but the support for what you're recommending, a moratorium, will be much greater if there are any whistleblowers that provide documented evidence out of the Wuhan Institute. Then it becomes really a high-level visible change and moratorium. So do you see any possibility of that?

Andrew Kimbrell: Yeah, the case is building. I mean that's what

Jonathan Latham's article says, and what

Petrovsky is saying. The case is building.

But I will just point out that hundreds of scientists came together in 2014 to get this moratorium done. It's really unusual to have a moratorium on research and science. And they got it done in 2014 because of the

fear of this bird flu research that was being done, that could lead to this fantastic, horrifying pandemic of 1.6 billion people dying. Well, that's still out there. And so I find it a little shocking that these experiments were approved in secret a little over a year ago, reapproved after they lifted the moratorium, and that there's no public debate about that.

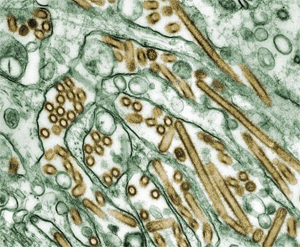

Ten years ago, the viral pathogen most in the news was not a coronavirus but influenza—in particular, a strain of flu, designated H5N1, that arose in birds and killed a high proportion of those who were infected. For a while, the virus made headlines. Then it became clear that nearly everyone who caught the bird-flu virus got it directly from handling birds. To cause a plague, it's not enough that a virus is an efficient killer. It also has to pass easily from one person to the next, a quality called transmissibility.

Around this time, Ron Fouchier, a scientist at Erasmus University in Holland, wondered what it would take for the bird flu virus to mutate into a plague virus. The question was important to the mission of virologists in anticipating human pandemics. If H5N1 were merely one or two steps away from acquiring human transmissibility, the world was in danger: a transmissible form of H5N1 could quickly balloon into a devastating pandemic on the order of the 1918 flu, which killed tens of millions of people.

To answer the question, scientists would have to breed the virus in the lab in cell cultures and see how it mutated. But this kind of work was difficult to carry out and hard to draw conclusions from. How would you know if the end result was transmissible?

The answer that Fouchier came up with was a technique known as "animal passage," in which he mutated the bird-flu virus by passing it through animals rather than cell cultures. He chose ferrets because they were widely known as a good stand-in for humans—if a virus can jump between ferrets, it is likely also to be able to jump between humans. He would infect one ferret with a bird-flu virus, wait until it got sick, and then remove a sample of the virus that had replicated in the ferret's body with a swab. As the virus multiplies in the body, it mutates slightly, so the virus that came out of the ferret was slightly different from the one that went into it. Fouchier then proceeded to play a version of telephone: he would take the virus from the first ferret and infect a second, then take the mutated virus from the second ferret and infect a third, and so on.

After passing the virus through 10 ferrets, Fouchier noticed that a ferret in an adjacent cage became ill, even though the two hadn't come into contact with one another. That showed that the virus was transmissible in ferrets—and, by implication, in humans. Fouchier had succeeded in creating a potential pandemic virus in his lab.

When Fouchier submitted his animal-passage work to the journal Science in 2011, biosecurity officials in the Obama White House, worried that the dangerous pathogen could accidentally leak from Fouchier's lab, pushed for a moratorium on the research. Fouchier had done his work in BSL-2 labs, which are intended for pathogens such as staph, of moderate severity, rather than BSL-4, which are intended for Ebola and similar viruses. BSL-4 labs have elaborate safeguards—they're usually separate buildings with their own air circulation systems, airlocks and so forth. In response, the National Institutes of Health issued a moratorium on the research.

What followed was a fierce debate among scientists over the risks versus benefits of the gain-of-function research. Fouchier's work, wrote Harvard epidemiologist Marc Lipsitch in the journal Nature in 2015, "entails a unique risk that a laboratory accident could spark a pandemic, killing millions.

Lipsitch and 17 other scientists had formed the Cambridge Working Group in opposition. It issued a statement pointing out that lab accidents involving smallpox, anthrax and bird flu in the U.S. "have been accelerating and have been occurring on average over twice a week."

"Laboratory creation of highly transmissible, novel strains of dangerous viruses... poses substantially increased risks," the statement said. "An accidental infection in such a setting could trigger outbreaks that would be difficult or impossible to control. Historically, new strains of influenza, once they establish transmission in the human population, have infected a quarter or more of the world's population within two years." More than 200 scientists eventually endorsed the position.

The proponents of gain-of-function research were just as passionate. "We need GOF experiments," wrote Fouchier in Nature, "to demonstrate causal relationships between genes or mutations and particular biological traits of pathogens. GOF approaches are absolutely essential in infectious disease research."

The NIH eventually came down on the side of Fouchier and the other proponents. It considered gain-of-function research worth the risk it entailed because it enables scientists to prepare anti-viral medications that could be useful if and when a pandemic occurred.

By the time NIH lifted the moratorium, in 2017, it had granted dozens of exceptions. The PREDICT program, started in 2009, spent $200 million over 10 years, sending virologists all over the world to look for novel viruses and support some gain-of-function research on them. The program ran out of funding in 2019 and was then extended.

-- The Controversial Experiments and Wuhan Lab Suspected of Starting the Coronavirus Pandemic, by Fred Guterl, Naveed Jamali and Tom O'Connor

Ralph Nader: Does Trump know about this?

Andrew Kimbrell: I have no idea what he knows ...

Ralph Nader: Because it's under his ...

Andrew Kimbrell: His capacity to take in information seems to me extremely limited since he doesn't read and ...

Ralph Nader: Let's put it this way. Since it was under his regime that this occurred, the reintroduction of this kind of research, does the White House know about this?

Andrew Kimbrell: Well, Fauci and Francis Collins were supportive of this kind of research. They were not obviously in favor of the moratorium.

A decade ago, during a controversy over gain-of-function research on bird-flu viruses, Dr. Fauci played an important role in promoting the work. He argued that the research was worth the risk it entailed because it enables scientists to make preparations, such as investigating possible anti-viral medications, that could be useful if and when a pandemic occurred.

The work in question was a type of gain-of-function research that involved taking wild viruses and passing them through live animals until they mutate into a form that could pose a pandemic threat. Scientists used it to take a virus that was poorly transmitted among humans and make it into one that was highly transmissible—a hallmark of a pandemic virus. This work was done by infecting a series of ferrets, allowing the virus to mutate until a ferret that hadn't been deliberately infected contracted the disease.

The work entailed risks that worried even seasoned researchers. More than 200 scientists called for the work to be halted. The problem, they said, is that it increased the likelihood that a pandemic would occur through a laboratory accident.

Dr. Fauci defended the work. "[D]etermining the molecular Achilles' heel of these viruses can allow scientists to identify novel antiviral drug targets that could be used to prevent infection in those at risk or to better treat those who become infected," wrote Fauci and two co-authors in the Washington Post on December 30, 2011. "Decades of experience tells us that disseminating information gained through biomedical research to legitimate scientists and health officials provides a critical foundation for generating appropriate countermeasures and, ultimately, protecting the public health."

Nevertheless, in 2014, under pressure from the Obama administration, the National of Institutes of Health instituted a moratorium on the work, suspending 21 studies.

Three years later, though—in December 2017—the NIH ended the moratorium and the second phase of the NIAID project, which included the gain-of-function research, began. The NIH established a framework for determining how the research would go forward: scientists have to get approval from a panel of experts, who would decide whether the risks were justified.

The reviews were indeed conducted—but in secret, for which the NIH has drawn criticism. In early 2019, after a reporter for Science magazine discovered that the NIH had approved two influenza research projects that used gain of function methods, scientists who oppose this kind of research excoriated the NIH in an editorial in the Washington Post.

"We have serious doubts about whether these experiments should be conducted at all," wrote Tom Inglesby of Johns Hopkins University and Marc Lipsitch of Harvard. "[W]ith deliberations kept behind closed doors, none of us will have the opportunity to understand how the government arrived at these decisions or to judge the rigor and integrity of that process."

-- Dr. Fauci Backed Controversial Wuhan Lab with U.S. Dollars for Risky Coronavirus Research, by Fred Guterl

So there was enough scientific angst about what was going on. But again, I think that we argue, we see these nuclear treaties going down the drain, and these are really existential threats to us. But we don't think of this genetic engineering of these pandemic viruses that are ongoing in these labs as threats, especially since there has been this total failure to have a strong biosecurity international effort. This is something we have to work together on. I'm certainly going to be working on it. We're going to Congress to try and get bipartisan agreement to get a moratorium or a ban on this kind of research in COVID, because we don't have to prove that gain-of-threat research didn't create it, we just have to show, as so many scientists have, that it is either probable or even just possible. That is enough. The Nuremberg Code said very explicitly that you should never do research whose threat to the public is greater than the advantage that you're getting. And this seems to me clearly an example of that. Additionally, there's a similar code in the InterAcademy Partnership [a global network], and I'm going to read it to you. This is the code that's supposed to be the ethics behind all biomedical research. And it says,

"Scientists have an obligation to do no harm. They need to take into consideration the reasonably foreseeable consequences of their own activities."

Well, this kind of research obviously violates that. It's just a small sector of the research that's going on, and it's fairly new because of the new technologies in synthetic virology and genetic engineering. But it represents an existential threat.

Ralph Nader: What you're saying in legal terms is the burden of proof is on the scientists, not on the people who fear the consequences of it or on the potential victims. It's on the scientists and those in Congress and elsewhere who fund them.

Let me quote your statement recently. This is Andrew Kimbrell:

"Unfortunately, many powerful forces at the NIH, World Health Organization, et cetera, have for self-interested reasons, including hundreds of millions in potential funding, continued to downplay the role of this profoundly hazardous research in the current pandemic, and its dangers in creating future pandemics."

You’re referring to the hazardous research where? And what are the self-interested reasons?

Andrew Kimbrell: Well, there are researchers who want to do this research, and they're doing it. I mentioned several by name. I don't know what it feels like to come home at dinner and say, "Hey, honey, I just created a novel pandemic bird flu that could kill 1.6 billion people if it got out of my laboratory." I can't think you could possibly explain that to yourself. It's done no good; hasn't helped anybody. The same is true with the research that Shi Zhengli was doing in the Wuhan Institute of Virology.

It hasn't come with a vaccine. It hasn't helped us with any coronaviruses. All it did was create the potential and the possible -- some of us think probable -- pandemic that we're facing. And we know that this kind of research is going on around the world, and I think some of it's probably being secretly done for biological weapons research. So we need to expose this.The genetic engineering movement has been very strong around the world. We've seen the dangers of genetic engineering bacteria and crops. We know the threats of trying to genetically engineer humans. We need to add to that, as part of our movement, to say that the genetic engineering of these pandemic viruses, to make them more threatening, by scientists who can do it but shouldn't do it, needs to be stopped, just like some of this other research. On an existential basis, it actually is even more threatening to the human population than other forms of genetic engineering.

Ralph Nader: Two questions. Why hasn't Congress had a congressional hearing on this in the House or Senate, since it's been going on a long time, and since Obama put a moratorium on it in 2014? You'd think the Democrats in the House would be interested in it, and the Science and Technology committee. And second, should there be an international treaty movement getting underway fast? Let's start with Congress.

Andrew Kimbrell: Yeah, I think there were, and again, I really want to give credit to the Cambridge Working Group. They haven't been speaking out lately, and I'm sorry they haven't, but the Cambridge Working Group did a great job. It's the group of scientists who got this moratorium done. Again, I'll mention Marc Lipsitch of Harvard, and Tom Inglesby at Johns Hopkins, who are both great scientists. We need them again. We need more hearings. We had them then, but that's six, seven years ago. We need them now urgently, because U.S. funding is a huge source in this. I will note that the No. 2 funder of the World Health Organization [WHO] after the United States is the Gates Foundation, not a country. The second greatest funding of the world happens to be with the Gates Foundation. We need people at the Gates Foundation, and we need these other countries to say, "You know what, we also are not going to support this particular jagged edge research, because it's very, very, very dangerous, and we shouldn't be doing it."

And yeah, if you look at the

Global Health Security Index released in October, they have a series of suggestions, which are very important recommendations that include United Nations' overview of this, and international treaties. And it reminds me how at the beginning, when we started looking at nuclear fission, when we looked at that level of danger to the world, we didn't do so well back then. Maybe we can do better now, and get this research that is only about 10 or 11 years old stopped, and say, "No, we're not going to do this; this is way too dangerous. We as a human population, as an international community, as an international research community, are going to say no to that small little viral research industrial complex, which is really small but very powerful. Just say no!"

Ralph Nader: Andy, there seems to be a massive indifference here that requires a civic jolt. And you're a well-known activist. You've worked with legislatures. You've worked with initiatives on the ballot. You've litigated and won a lot of cases, especially in the Ninth Circuit against Monsanto and others. Tell us exactly what action your organizations are taking. And are you going to write a letter to Bill Gates? So exactly what actions, so people can attach themselves to it, and support them.

Andrew Kimbrell: Thank you, Ralph. Yes, I think we are going to specifically launch a major campaign among scientists. This is the National Center for Technology Assessment, and I'm sure we'll get many other groups with us that were supporting the first moratorium. The first thing we want to do is get the moratorium back. We want to say, "Lifting it during the Trump Administration was wrong; getting that moratorium done in the Obama administration was the right thing to do." We need to make it a little bit more extensive. We need to make sure it's more carefully monitored than it was, but still, it's not like we're starting from scratch. We did it right, and then it got lifted during the Trump administration. We want to reassert it. We may have bipartisan support from Democrats and Republicans. So we can go to Congress, and we think that's going to be more effective. There is possible litigation under the National Environmental Policy Act, and we're looking at that as well. And we want to look to some of our international partners that we've already reached out to to get some support, for example, from our friends at the European Union who are part of the GMO movement, which is a huge movement, as you know, around the world; and see if we can get them to understand how also banning genetic engineering of viruses fits in with the larger problems of dealing with the regulation and the moratoriums on genetic engineering.

The idea is to first start in this country. Because U.S. funding is so important to all of these things, let's get that moratorium back on track here. Let's work in Congress. Let's work in the regulatory area, but also let's do a little litigation as well. Then we need to look at the international community, and hopefully folks at the Global Health Security Index, and others who have recommended the United Nations take an active role in this for an international treaty. We also need to look back to the 1972 biological warfare convention, don't we, Ralph? We need to make sure that that's being enforced, because it won't help us that much to get rid of the medical part of this research if it's still ongoing in the biological warfare research.

Ralph Nader: Well, to frame all this, what about an open letter by your organization, signed by other coalition groups, to Donald Trump, and the leadership in the House and Senate from both parties? A comprehensive letter.

Andrew Kimbrell: Yeah, I think that's what we're going to need. And we're going to need some prominent scientists [to sign] onto that letter. And I think that we need to move the debate from tit-for-tat, China vs. anything else ,and trying to weaponize this discussion for political gains, whose purpose is for Trump or anyone else, and get to the real nub of it, which is that we can't stop natural pandemics from happening in nature -- that's going to happen -- but we can stop pandemics that originated in the laboratories around the world because people are deliberately creating them in those laboratories.

Ralph Nader: So on the open letter, to frame it for the media and for the citizenry, are you all for it? Can you do it?

Andrew Kimbrell: Yeah, absolutely.

Ralph Nader: Okay. Then we will look forward to it. We'll get people to sign it, and all these scientists you referenced shouldn't have any trouble signing it, because that's the only way you're going to get high-level visibility to something that is often not public, but proprietary, secret, you name it. When do you think you can get this done, Andy?

Andrew Kimbrell: I'm looking to this summer to really get this campaign on the road, and to get scientists lined up. I've already communicated with dozens of scientists. So we're going to put this together. There are some language issues. We want to make sure that the moratorium is correctly worded. We've got some good lawyers and good scientists working on that. So, yeah, we're going to be watching for it this summer, folks. So stay tuned.

Ralph Nader: And how can people get more information about your organization? What's your website?

Andrew Kimbrell: They can get more information through the

http://www.icta, International Center for Technology Assessment, dot org. And there'll be more and more information on that website as this campaign really takes off this summer.

Ralph Nader: Okay. Steve, David, any concluding questions?

Steve Skrovan: Yeah. Andrew, how does a virus escape from a lab?

Andrew Kimbrell: There's numerous ways. It can escape because somebody didn't correctly wash their hands; didn't dispose of their clothing appropriately; it can escape through an animal that's been infected and not properly disposed of; it can escape through one lab sending the virus to another lab under the mistaken view that that virus has been killed or is disabled, and it hasn't been. This happens a lot actually. It's one of the major ways ... we did it with anthrax. CDC sent out a whole bunch of anthrax to about 100 labs around the world saying, "We killed this bacteria, don't worry about it," and it turns out it wasn't killed. So accidents can happen between lab transportation as well. But people can have a bad day; people don't pay attention; people are ill; or an animal is not properly disposed of; and viruses are sent in an unsafe manner to another laboratory. There are a number of vectors that can make that happen.

Steve Skrovan: So they're working on this theoretically as something with good intentions? They're working on this to try to get to the bottom of how you get a vaccine for a SARS coronavirus?

Andrew Kimbrell: No, this is not vaccine research. In vccine research, you try and kill, or make a vaccine less virulent in order to use it for vaccine. This is specifically to make that virus more virulent, to make that virus more transmissible and more infective. And the only reason they have for doing this outside of biological weapons research is because they say maybe this could happen out in nature, the combination they just did in the lab. And if it does, they could be ready for it. That's pretty much it. That's their rationale.

Steve Skrovan: Okay.

Ralph Nader: Well, very good. We're out of time, Andy. And I'm sure our listeners will send some questions in. This is a calm discussion; it's not going in one direction after another. And we clearly have to understand that even if we do everything right in the U.S., there are other countries that may have secret biological warfare research, or even worse lab security. So we've got to come together as a planet here with an international treaty. There are international treaties on weapons of mass destruction, as a precedent, to go to work on this. So we look forward to your open, comprehensive letter to Trump and the leadership on both sides in the House and Senate to get them involved, and get them on top of it. They did it once in 2014; they can do it again.

Andrew Kimbrell: And Ralph, I think that the point you make is so important, that if these technologies develop, and we're talking about synthetic biology, synthetic virology, the technology develops but our capacity as a world community, as an Earth community, to deal with it has not caught up with that technology. So it's a calm conversation, but for me inwardly I'm not so calm, more like Shi Zhengli, it's hard to sleep sometimes knowing that these technologies could go any further in creating these essential threats similar to nuclear and other genetic engineering. And as a global community, maybe COVID-19 is a wake-up call. I hope it is, and that we can say that we can no longer approach this just nationally. We cannot approach it as a political football, or weaponizing it on cable TV shows. That's nonsense. This is far too serious for that. It's far too important. We're looking towards the future, and future generations, and health, security and safety issues now and we need to deal with them comprehensively.

Ralph Nader: That's what I meant by calm. You can have a calm discussion and be very super urgent, which is what this whole interview is all about. Thank you very much. We've been talking with Andrew Kimbrell, who is, among other things, a founder of the Center for Food Safety, as well as director of the International Center for Technology Assessment. To be continued. We look forward to your comprehensive letter, and all kinds of groups, I'm sure, will want to join in. There's no time to lose here.

Andrew Kimbrell: No, no. I appreciate it, Ralph. As always, thanks for having me on. Stay healthy and safe, everybody, okay? To be continued.

Ralph Nader: Yeah. You're welcome.

Andrew Kimbrell: Thanks, guys. Thanks, Dave. Thanks, everybody.