by Dhaatri Resource Centre for Women and Children -- Samata

HAQ: Centre for Child Rights

In partnership with mines, minerals & People

March, 2010

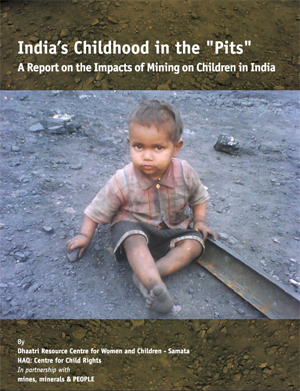

India’s Childhood in the "Pits": A Report on the Impacts of Mining on Children in India

Published by:

Dhaatri Resource Centre for Women and Children-Samata, Visakhapatnam

HAQ: Centre for Child Rights, New Delhi

In partnership with: mines, minerals & PEOPLE

Supported by: Terre des Hommes Germany, AEI & ASTM Luxembourg

March 2010

Any part of this report can be reproduced with permission from the following:

Dhaatri - Samata,

14-37-9, Krishna Nagar,

Maharanipet, Visakhapatnam-530002

Andhra Pradesh

Email: [email protected]

HAQ: Centre for Child Rights

B1/2 Malviya Nagar

New Delhi-110017

Email: [email protected]

http://www.haqcrc.org

Credits:

Research Coordination: Bhanumathi Kalluri, Enakshi Ganguly Thukral

Field Investigators: Vinayak Pawar, Kusha Garada

Documentation Support: Riya Mitra, G.Ravi Sankar, Parul Thukral

Report: Part 1- Enakshi Ganguly Thukral and Emily

Part 2- Bhanu Kalluri, Seema Mundoli, Sushila Marar, Emily

Design and Printing: Aspire Design

List of Abbreviations

AEI – Aide à l’Enfance de l’Inde

ANM – Auxiliary Nurse cum Midwife

ARI – Acute Respiratory Illness

ASER – Annual Status of Education Report

ASTM – Action Solidarite Tiers Monde

AWC – Anganwadi Centre

BCCL – Bharat Cooking Coal Limited

BGML – Bharat Gold Mines Limited

BHEL – Bharat Heavy Electricals Limited

BIFR – Board for Industrial and Financial Reconstruction

BPL – Below Poverty Line

BPO – Business Process Outsourcing

BRC – Block Resource Coordinator

BSL – Bisra Stone Lime Company Limited

CCL – Central Coalfields Limited

CHC – Community Health Centre

CICL – Child in Conflict with Law

CMPDI – Central Mine Planning and Design Institute

CNCP – Child in Need of Care and Protection

CSE – Centre for Science and Environment

CSR – Corporate Social Responsibility

Cu m – cubic metres

CWSN – Children With Special Needs

DISE – District Information System for Education

DP camp – Displaced Persons’ Camp

ECL – Eastern Coalfield Limited

EIA – Environmental Impact Assessment

FDI – Foreign Direct Investment

FIR – First Information Report

FPIC – Free Prior and Informed Consent

GAFSCA – Gangpur Adivasi Forum for Social and Cultural

Awakening

GDP – Gross Domestic Product

GSDP – Gross State Domestic Product

Ha – hectare

HAL – Hindustan Aeronautics Limited

HDI – Human Development Index

HIV/AIDS – Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired

Immuno Deficiency Syndrome

ICDS – Integrated Child Development Scheme

IIPS – International Institute for Population Sciences

ILO – International Labour Organization

IMR – Infant Mortality Rate

IPEC – International Programme on the Elimination of Child Labour

IT – Information Technology

KGF – Kolar Gold Fields

KMMI – Karignur Mineral Mining Industry

LWSI – Lutheran World Service India

MASS – Mitra Association for Social Service

MCL – Mahanadi Coalfields Limited

MDGs – Millennium Development Goals

MLPC – Mine Labour Protection Campaign.

mm&P – mines mineral and PEOPLE

MMDR Act – Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) Act

MP – Madhya Pradesh

MW – Megawatt

NACO – National AIDS Control Organisation

NALCO – National Aluminum Company

NCLP – National Child Labour Project

NCRB – National Crime Records Bureau

NFHS – National Family Health Survey

NGO – Non–Governmental Organisation

NIOH – National Institute for Occupational Health and Safety

NMDC – National Mineral Development Corporation

NREGA – National Rural Employment Guarantee Act

NSSO – National Sample Survey Organisation

OBC – Other Backward Classes

PAP – Project Affected Persons

PDS – Public Distribution System

PHC – Primary Health Centre

PIO – Public Information Officer

PKMS – Pathar Khadan Mazdoor Sangh

POSCO – Pohang Iron and Steel Company

PSSP – Prakrutiko Sampado Surakshya Parishad

READS – Rural Education Action Development Society

R&R – Rehabilitation and Resettlement

Rs – Rupees

RTI – Right to Information

SAIL – Steel Authority of India Limited

SCCL– Singareni Collieries Company Limited

SC – Scheduled Caste

SDP – State Domestic Product

SEEDS – Social Economical Educational Development Society

SEZ – Special Economic Zone

SGVS – Society of Gram Vikasa Saradhi

SHG – Self Help Group

SOP – Superintendent of Planning and Implementation

Sq km – square kilometres

STD – Sexually Transmitted Disease

ST – Scheduled Tribe

TB – Tuberculosis

TDH – Terre des Hommes

UAIL – Utkal Alumina International Limited

UCIL – Uranium Corporation of India Limited

USA – United States of America

VRDS – Vennela Rural Development Society

VRS – Voluntary Retirement Schemes

Table of Contents

• About the Study

• Mining Children — Introduction and Overview

• Part I

o National Overview

• Part II: State Reports

o 1. Karnataka

o 2. Maharashtra

o 3. Rajasthan

o 4. Madhya Pradesh

o 5. Chhattisgarh

o 6. Jharkhand

o 7. Orissa

o 8. Andhra Pradesh

• Part III: Summary and Recommendations

• Part IV

• Appendix- Our Experience with Right to Information Act

• Annexures

o a) Tables

o b) Glossary of Terms

About the Study

This study has been conducted jointly by HAQ: Centre for Child Rights and Samata in close partnership with the national alliance, mines, minerals and People (mm&P) network and Dhaatri Resource Centre for Women and Children, and supported by Terre des Hommes Germany (tdh), AEI & ASTM Luxembourg. The work follows on from an earlier fact-finding mission that was carried out in the iron ore mines of Bellary district, Karnataka. As well as being the first study to cover these issues in a comprehensive way, the study aims to form the basis for mobilisation and advocacy on this issue. We hope that, along with the mm&P network, we will be able to take forward this work and to campaign to bring real improvements in the lives of children affected by mining in India.

This report aims to cover the three phases of mining — premining areas (where projects are being proposed and land needs to be attained), current mining areas (where mining is already taking place) and post-mining areas (where mining operations were significant but have now ceased).

Field research was carried out in eight states to cover a range of different mining situations, as well as a range of minerals being mined in India today. The states covered were: Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Rajasthan, Orissa, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand. In Orissa we undertook case studies in a number of different sites as Orissa is a state most impacted by mining and has been the focus of further mineral expansion.

Methodology

This report is compiled from a combination of information gathered in the field and from secondary data. The sites for fieldwork were chosen to ensure a range of minerals, both minor and major minerals, were covered as well as a wide geographic space. One of the most important factors was the presence of a local organisation or an mm&P partner. This was a priority for two reasons, to secure local support with the research, and to ensure that local groups will take the campaign forward and use the study as a basis for mobilisation and advocacy in their states.

Not all background data was available through Census statistics or in other public domains. Therefore, the decision was made to use the Right to Information (RTI) Act to gather missing information. RTIs were sent to a number of government departments, including state-owned mining companies, to find out the number of children working in mines, the number of people displaced by projects, various health statistics for people living in these districts and other information that is not readily available. (See end of Part 2 for responses to RTIs filed).

The main methodology used for field case studies was to understand the overall development indicators of the children living around the mines while also identifying the children working in the mines, the nature of their work and working conditions and how their social life is impacted due to the external influences of the complex ad hoc communities of workers, truckers, contractors, traders and other players who form an amorphous and unscrupulous floating population around the mines. This was done through visits to villages, schools, anganwadi centres, primary health centres, orphanages, company run schools and hospitals, meetings with panchayat leaders, village elders, women’s groups, workers’ unions, local officials and NGOs, as well as visits to the mine sites.

List of states and districts visited

• Pune and Nashik districts, Maharashtra, June 2009 (follow up in September 2009)

• Koraput and Rayagada districts, Orissa, June 2009 (follow up in October 2009 and in January-February 2009)

• Kolar and Bellary districts, Karnataka, June 2009 (follow up in Bellary in December 2009)

• Keonjhar district, Orissa, July 2009 (follow up in February 2009

• Jodhpur, Jaisalmer and Barmer districts, July 2009 (follow up in Jodhpur in October 2009)

• Panna district, Madhya Pradesh, August 2009

• Chittoor, Cuddapah, Visakhapatnam districts, Andhra Pradesh, June, August and October 2009

• Cuddalore district, Tamil Nadu, August 2009

• Hazaribagh district, Jharkhand, September, 2009

• Raigarh district, Chhattisgarh, November 2009

• Sundergarh district, Orissa, November 2009

Challenges

Over the course of the research, the study team faced a number of challenges.

The first challenge was the choice of sites. A first list of sites based on choice of minerals, location and presence of an mm&P partner organisation was made. However, some of these sites had to be later dropped, either due to a lack of adequate information or lack of capacity of the partner to provide the necessary support.

This was a time-bound research project. That meant that the project period coincided with the monsoons, which rendered some of the mining sites originally chosen inaccessible.

Despite seeing the overall impact of mining on their lives, communities were not always able to identify those that directly impacted children only. Since this study focussed on the impacts on children, this proved a major challenge for the team. It is difficult even for local organisations campaigning on rights of mining affected communities to provide tangible data with respect to children as impacts and problems are not directly visible on children. Although local groups are knowledgeable about the presence of child labour and other issues, threats from mining and political powers make it dangerous for them to directly confront the state on issues concerning children.

Mining operations are politically sensitive and highly politicised making it difficult to collect information related to children and mining because of the sensitive nature of this issue. People were nervous to talk, as they feared negative consequences. In terms of direct access, it is always difficult to get the opportunity to talk to children first-hand and this is certainly the case with regard to mining. Researchers were cautious to approach children at mine sites, in case of repercussions for these children. When communities were interviewed in their villages, it tended to be the elders who were most vocal in answering questions. In addition to this, primary health centres were unable to provide quantitative data on illnesses or diseases. Schools, where they existed, as in many other parts of the country were often without teachers present at the time of the fieldwork. Therefore, the difficulty in collecting quantitative data and figures meant that we only managed to get indicative information about the impacts of mining on children.

Non-availability of secondary information was yet another challenge. Applications under the Right to Information Act were filed to get relevant information. However this did not prove easy. To be able to get information under the RTI Act, 2005, it is critical to send the application to the right person. Interestingly this experience itself proved to provide important learning in the context of the study.

About this report

This report combines both secondary data as well as primary data. It has been presented in two parts. Part I is the national overview which aims to provide a summary of the huge quantity of data obtained during field research. Part II consists of state reports based on both secondary information about the state and its mining activities as well as case studies from mining sites where field work was undertaken. Part III is summary and detail recommendation and Part IV is the appendix that details our experience with using the Right to Information Act for this study.

Mining Children -- Introduction and Overview

India is endowed with significant mineral resources. The constant endeavour of humans to mine more and more resources from the earth has been going on for centuries. Metals, stones, oil, gas and even sand are all mined. Indeed, steel, aluminum and other plants have come to be a symbol of progress and industrial growth, while fossil fuels and coal are mined for our ever-increasing need for energy. Every time a mining operation begins, it is with promises of growth and development, yet these promises are rarely delivered.

Mining has, throughout history, been a symbol of the struggle between human need and human greed; the human need to dig into the earth and take control over its resources. Industry, infrastructure and investments have been decisively stated as basic vehicles to drive India into this race, which automatically translates into mineral extraction and processing being of utmost importance to implement this dream. Further, development visions are based on certain premises built into public thought processes. The first of these premises is that mining brings economic prosperity at all levels of the country — national and local. It has been based on the principle that the high revenues generated by mining activities will convert poverty stricken and marginalised communities and workforce into economically grounded communities with positive developments in employment generation, health, education, local infrastructure and the creation of a diversified opportunity base.

Overview on Mining

India currently produced 89 minerals out of which 4 are fuel minerals, 11 metallic, 52 non-metallic and 22 minor minerals (such as building stones). Mining for fuel, metallic and non-metallic industrial minerals is currently undertaken in almost half of India’s districts.1 Coal and metallic reserves are spread across Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Jharkhand, Orissa, Maharashtra and Andhra Pradesh. Iron ore deposits are located in Orissa, Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand in the north, and Goa and Karnataka in the south. Limestone is found in Himachal Pradesh in the north, to Andhra Pradesh in the south and from Gujarat in the west to Meghalaya in the east. In terms of mineral deposits, Jharkhand, Orissa and Chhattisgarh are the top three mineral bearing states.2

The contribution of the mining and quarrying sector to India's GDP in 2008-09 was Rs. 648.91 billion -- a mere 1.94 per cent of the total GDP.3 However, the demand for metals and minerals in India and in other developing countries has led to a steady growth in the country’s mineral industry.4 Mining grew by 4.7 per cent in 2008-09 over the preceding period and with the global recession hitting India, the mining and quarrying industry was the only segment of the economy not to experience steep deceleration of growth rates.5 However, what needs to be remembered is that in terms of the galloping Indian economy, mining makes only a marginal contribution.

In the 2008 National Mineral Policy, the government recognises that:

“As a major resource for development, the extraction and management of minerals has to be integrated into the overall strategy of the country’s economic development. The exploitation of minerals has to be guided by long-term national goals and perspectives.”

However, closer observation of the current mining sector reveals that mineral production is being viewed by both the central and state governments as a means of short-term revenue generation and to fuel current economic growth rates, as opposed to being considered holistically as part of the country’s wider, more long-term development goals, human development indicators and preservation of the environment and other natural resources such as water.

With the new economic policy in India, there have been a number of changes in the mining sector. Although traditionally in the hands of the public sector, there has been increasing privatisation since the early 1990s, and more and more mines are now privately owned. Foreign direct investment has been a thrust area for the sector, with both the central and state governments pushing for liberalisation and deregulation in not only the Coal Nationalisation Act and labour laws, but also in other related areas such as the environment. It has also impacted employment due to the enforcement of Voluntary Retirement Schemes (VRS) on mine workers. The Fifth Scheduled Areas, areas which are constitutionally demarcated for tribal populations, are being opened up for foreign direct investment and private industries, primarily mining, leading to deforestation and displacement of tribals. Most alarmingly, there has been a huge increase in the informal sector mining activities through sub-contracting mining and quarrying.

But mining is not the subject of this study. This study is about the relationship between children’s rights and mining. It attempts to address the question — what is the impact of mining on children? According to the most recent Indian Census carried out in 2001, children constitute over 40 per cent of India's population, many of whom live in mining areas. These we refer to as “Mining Children” in this report.

A fact-finding study in 2005 in the iron ore mines of Hospet in Bellary District, Karnataka, for the first time, brought home to the organisations involved in this study, the immense impact mining has on the lives of children. It became imperative to follow that fact-finding study with a more systematic research to gain a better understanding.

India boasts of several legal protections for children, with the Right to Education being the latest fundamental right. These laws are strengthened by positive schemes to bring children out of poverty and marginalisation. The paradox of mining lies in the fact that the mining industry or the mining administration is not legally responsible for ensuring most of the rights and development needs of children. The mess that is created in the lives of children as a result of mining is now addressed by other departments like child welfare, education, tribal welfare, labour and others, which makes for an inter-departmental conflict of interest and leaves ample room for ambiguities in state accountability. In this process, the child is being forgotten. Hence, the glaring heart-rending impacts of mining on children have technically few legal redressal mechanisms to bring the multiple players to account.

While there is some documentation and research available on the impact of mining on communities in general, apart from scattered and anecdotal information, very little information is available on the impact of mining on children in all its dimensions. Research on mining and children has tended to focus solely on the aspect of child labour, which again is restricted to minerals that are normally exported and have the potential to shock the western consumer. The multitude of other ways in which children are impacted by mining have been completely neglected. Needless to say, neither the groups and campaigns that focus on mining issues, nor those working with children, have paid this issue the attention it deserves.

This report provides but a glimpse into the lives of children living, working, affected by and exploited by mining in India. We hope that the microcosm of children we touched through this report evokes a national reflection on what could be the plight of millions of children affected by mining in India.

It is hoped that this report will yet again bring to national debate the paradox of “India’s inclusive growth” that still ignores the majority of children. When national sentiments are stirred by the rhetoric of children being the future of our nation, it is important to assess for ourselves whether our development models are actually geared towards creating a future for India’s children, or are instead, providing a nation with little present or future for the majority of our children. It therefore asks the question, “How do we as a nation want to measure ourselves as achieving human development?”

This study shows how the development aspirations created by our policy makers and political leadership create a strong likelihood for future divides between the children of this country, furthering both the socio-economic divide and the urban-rural divide. Among the adivasi and dalit children, the displacement, impoverishment and indebtedness caused by mining and its ancillary activities shows a dearth of opportunities for them to access even basic rights such as primary education and healthcare. That they are being forced to take on adult economic roles in the most exploitative conditions in order to help their families survive, is certainly not an indicator that sets us on track to achieve the Millennium Development Goals (MDG) goals emphasised in the 11th Five Year Plan especially for these social groups. This paves the route to socio-economic disparities in India’s children.

This study also shows that children and their communities are not part of the growth and development that mining promises. For example, it is over 30 years since the NALCO mining project, a public sector undertaking in the Koraput District of Orissa began. In these 30 years, the data from the case study reveals that there has been little upward mobility for the children of affected families, either educationally or economically. This is the fate of those affected by a public sector project where social responsibility is intended to be the principal agenda. There does not appear to be a single mining project that has fulfilled the rehabilitation promises in a manner that has improved the life of affected communities nor have they set a precedent for best practices that the government can set as a pre-condition to private mining companies. Moreover, there has been no assessment or stock taking of the status of rehabilitation especially with regard to the status of children.

The findings from this study provide a strong reason for an urgent comprehensive assessment of the status of children in mining areas — children of mine workers as well as of local communities, child labour engaged in mining and the status of the institutional structures for them. It also calls for addressing the glaring loopholes in the law, policy and implementation related to mining in general, and private and small scale/rat hole mining in particular that are related to children, to develop guidelines for migrant labour and the un-organised sector and pre-conditions that need to be fixed before mining leases are granted. Foremost is the need for strengthening protection mechanisms for children and campaigns against child labour in these regions.

What is the Definition of a “Child”?

A key challenge for child rights work in India is the confusion around the definition of a child in terms of age. The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child, which was adopted in 1989 and ratified by India in 1992, defines a child as “every human being below the age of 18.” Indian legislation also makes 18 years the general age of majority in India.6 However, other laws passed in India cause confusion in this area, with many laws defining childhood as only up till 14 years of age. For example, although children have been banned from working in hazardous occupations, which includes mining and quarrying, for this purpose, a child is only considered as a person up to 14 years -- for children between 15 and 18, there is no applicable regulation.7

This has also been witnessed with the passing of the recent Right to Education Act in 2009, which guarantees all children between 6-14 years the right to education, but no such guarantee exists for children 15 and above. As organisations committed to the rights of all children in India, in this study, HAQ and Samata will consider the impacts of mining on children up to the age of 18 years. However, there are serious limitations in terms of statistics, as the majority of statistics, such as the Census 2001, only calculates the number of working children up till the age of 14.

Law And Policy

International Standards

The UN Convention on the Rights of the Child includes the rights for children to be protected from hazardous work. Children have the right to be protected from economic exploitation and from performing any work that is likely to be hazardous or interfering with the child’s education, or to be harmful to the child’s health or physical, mental, spiritual, moral or social development. The Convention also recognises the right of the child to education and requests State Parties to take measures to encourage regular attendance at schools and the reduction of dropout rates, which is a frequent problem among working children.

In addition, almost all work performed by children in mining and quarrying is hazardous and considered to be one of the worst forms of child labour, defined by the Worst Forms of Child Labour Convention, 1999 (No. 182).8 India has not ratified this convention, and indeed activists and campaigns against child labour too are not in favour of ratifying a convention that distinguishes between hazardous and nonhazardous forms of labour. Their argument is that all forms of labour or indeed, work that denies children their basic rights, is exploitative and hence hazardous, and hence must be banned.

Bedi was also out of tune with the new direction of the Communist Party of India, which had swung sharply to the left, abandoning working with what were termed 'bourgeois' parties for support for peasant insurrections, notably in Telangana in southern India. Bedi's advocacy and implementation of the most radical measures in the 'New Kashmir' manifesto, the redistribution of land which turned hundreds of thousands of labourers into peasant cultivators and greatly alleviated rural indebtedness, was seen within the CPI as promoting reformism over revolution.Now this was the one act which earned me the severest condemnation from the Communist Party, as to why all these measures were not brought about in the Telangana manner: that is by murder of officials, murder of landlords, and then taking over lands and all that. To that I said, 'I have never come across a more stupid approach than this. When the entire national movement was adopting the programme, which I myself had drafted, and then the entire national movement plus the government ... without a single mishap the whole thing was implemented. You don't realize than [sic] in Kashmir it was not just a mere handing over of power to the national movement. It was virtually, if you look at it realistically, a seizure of power. Telangana means that you are too set and rigid in your pattern; that because Kashmir has not followed the bloody path of killing and murder, it is the wrong way.'16

This sharp (though unpublicised) difference, Bedi said, led to what amounted to his expulsion from the Communist Party.

-- The Lives of Freda: The Political, Spiritual and Personal Journeys of Freda Bedi, by Andrew Whitehead

Mining leads to forced evictions. General Comment 7 adopted by the UN Committee for Economic Cultural and Social Rights on Forced Evictions encourages State Parties to ensure that “legislative and other measures are adequate to prevent and if appropriate, punish forced evictions carried out without appropriate safeguards by private persons or bodies.”9

National Laws and Policy

The Constitution of India, along with a whole host of laws and policies, recognise and protect the rights of all children in India. The National Child Policy of 1974 and the more recent National Plan of Action for Children 2005, along with the Eleventh Five Year Plan, lay down the roadmap for the implementation of these rights. These include the rights to be protected from exploitation and abuse and the right to free and compulsory education. These laws are strengthened by positive schemes to bring children out of poverty and marginalisation. But then these are for all children. Very few laws provide any protection or relief to mining children in particular or address their specific situation. This is because the principal job of the Ministry of Mines is to mine. Hence, many of the violations and human rights abuses that result from mining, especially with respect to children, are not the mandate of the mines ministry to address. The responsibility lies elsewhere, and therefore leads to conflict of interest between departments, in which the child falls between the cracks.

In the laws that deal with mining, many do not address the needs and rights of children, or even human beings in general. For example, there are several laws and policies that govern mining in the country,10 which include central as well as state laws and policies. There are also policies and laws that deal with rehabilitation and resettlement of those displaced by the mining project,11 as well as polices for specific minerals such as coal.12 Although people are the most affected, directly or indirectly, when mining operations take place, most of these laws and policies that deal with mining mention little or nothing about people except as labour.

Not surprisingly, children find absolutely no mention, although they may lose access to education, healthcare and other facilities; be affected by pollution and other environmental impacts; be pushed into joining the labour force and end up unskilled and illiterate forever as a result of mining.

Child labour is one of the most vicious impacts of mining that one sees. However, laws to address the employment of children in such hazardous conditions are weak. The Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986, prohibits the employment of children below the age of 14 in mines (underground and underwater) and collieries (Schedule Part A). It also prohibits employment of children in certain mining related processes listed in Schedule B.13 This is a huge gap in the law because it does not unilaterally ban employment of children in all mining, thereby leaving them vulnerable to abuse and exploitation. Even while prohibiting the employment of children in mines, the Mines Act leaves open a window of opportunity for exploitation. While the Mines Act, 1952, and the Mines (Amendment) Act, 1983, lay down that no person below 18 years of age shall be allowed to work in any mine or part thereof (Section 40) or in any operation connected with or incidental to any mining operation being carried on (Section 45), it simultaneously allows for children of 16 years to be apprentices and trainees. It also leaves it to the discretion of the Inspector to determine whether the person is a worker or apprentice/trainee and fit to work (Section 43.1). The National Mineral Policy has one line under its section on infrastructure development that “a much greater thrust will be given to development of health, education, drinking water, road and other related facilities…”, failing to mention who will do it and how.

The law that can be most effective in dealing with child labour in mining as well as any other form of vulnerability arising out of mining, is the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection) Act 2000, Amended 2006, which defines children as persons up to the age of 18 and deals with two categories of children — the Child in Need of Care and Protection (CNCP) and the Child in Conflict with Law (CICL). Section 2d defines a child in need of care and protection as one who is exploited or abused or one who is vulnerable to being abused or exploited. It includes children already or vulnerable to displacement and homelessness, trafficking, labour etc.

Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) (MMDR) Act, 1957, is an Act stated to undertake mining and use of minerals in a “scientific” manner. This is the primary Act, which is slated for amendment, concerned with mining in India under the National Mineral Policy framework. The rules laid under this Act mainly relate to mine planning, processes of mining, the nature of technology, procedures and eligibility criteria for obtaining mining leases and all aspects related to mines. It does not give any reference to the manner in which mining is to take place, from the social context, except for some broad guidelines in terms of environment, rehabilitation and social impacts. Given the huge negative impacts of mining on children, specific pre-conditions should be clearly laid out prior to granting of mining leases, where mining companies have to indicate concrete actions for the development and protection of children. In order to undertake responsible mining, unless some of the following social impacts and accountability, particularly, with regard to children, are incorporated within the Act and the Mine Plan, violation of children’s rights will continue in mining areas.

The Rehabilitation and Resettlement Bill, 2009 was passed by the Lok Sabha on February 25, 2009. However, it has since lapsed and not become an Act. As with all generic laws and policies, there is no special recognition accorded to children except to mention educational institutions as part of social impact assessment and orphans in the list of vulnerable persons.14 It says that while undertaking a social impact assessment under sub-section 4(2), the appropriate government shall take into consideration facilities such as health care, schools and educational or training facilities, anganwadis, children’s parks15 etc. and this report has to be submitted to an expert group in government, which must include “the Secretary of the departments of the appropriate government concerned with the welfare of women and children, Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes or his nominee, ex officio.” 5(2b). In a letter to the Minister for Rural Development, the Chairperson of the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights had pointed out that a review of the status of children in areas of displacement due to development programmes as well as disaster and conflicts, shows that most rehabilitation programmes do not take into account the impacts on children. Because displacement can lead to a violation of rights of children in relation to their access to nutrition, education, health and other facilities, it calls for an impact assessment on children and their access to entitlements. This has to be gender and age specific.16

The National Rehabilitation and Resettlement Policy neglects to mention children as affected persons and therefore fails to recognise or acknowledge the ways in which children are specifically impacted by displacement for any project including mining. Impacts on children are different from those on adults. Yet no mention is made in this policy of the effect this displacement will have on their access to food, education and healthcare, as well as their overall development.

Impacts

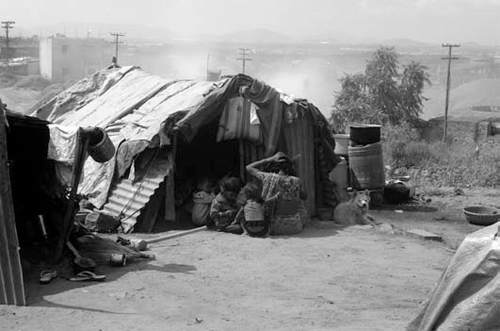

Children are affected directly and indirectly by mining. Among the direct impacts are, the loss of lands leading to displacement and dislocation, increased morbidity due to pollution and environmental damage, consistent degeneration of quality of life after mining starts, increase in school dropouts and children entering the workforce.

The indirect impacts of mining, often visible only after a period of time, include a fall in nutrition levels leading to malnutrition, an increase in diseases due to contamination of water, soil and air, and increased migration due to unstable work opportunities for their parents.

It is paradoxical that while mining is touted as heralding prosperity and growth and if it is meant to bring in a better life, then why is this not visible in the lives of local people –- men women and children –- whose lands are being mined, or who have been brought there as labour to mine the lands?

Direct and Indirect Impacts of Mining on Children

1. Increased morbidity and illnesses: Mining children are faced with increased morbidity. Children are prone to illness because they live in mining areas and work in mines.

2. Increased food insecurity and malnutrition: While almost 50 per cent of children in many states across the country are malnourished, mining areas are even more vulnerable to child malnutrition, hunger and food insecurity.

3. Increased vulnerability to exploitation and abuse: Displaced, homeless or living in inadequate housing conditions, forced to drop out of schools, children become vulnerable to abuse, exploitation and being recruited for illegal activities by mafia and even trafficking.

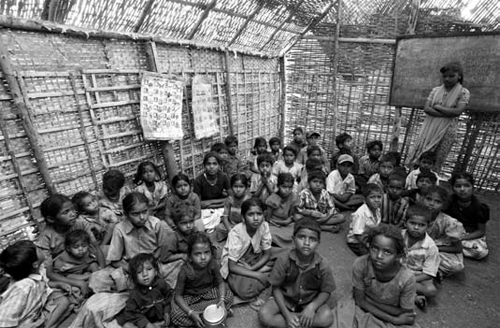

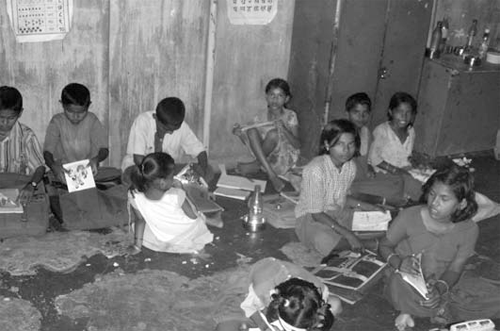

4. Violation of Right to Education: India is walking backwards in the mining affected areas with respect to its goal of education for all. Mining children are unable to access schools or are forced to drop out of schools because of circumstances arising from mining.

5. Increase in child labour: Mining regions have large numbers of children working in the most hazardous activities.

6. Further marginalisation of adivasi and dalit children: Large-scale mining projects are mainly in adivasi areas and the adivasi child is fast losing his/her Constitutional rights under the Fifth Schedule, due to displacement, land alienation and migration by mining projects. As with adivasi children, it is the mining dalit children who are displaced, forced out of school and employed in the mines.

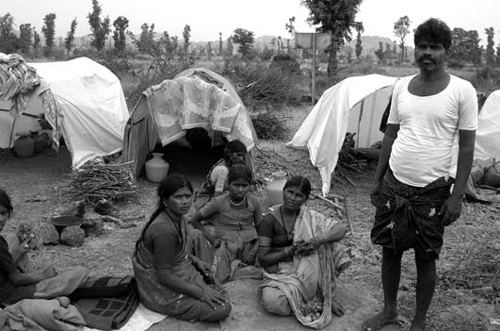

7. Migrant children are the nowhere children: The mining sector is largely dependent on migrant populations where children have no security of life and where children are also found to be working in the mines or other labour as a result of mining.

8. Mining children fall through the gaps: Children are not the responsibility of the Ministry of Mines that is responsible for their situation and the violation of their rights. The mess that is created in the lives of children as a result of mining has to be addressed by other departments like child welfare, education, tribal welfare, labour, environment and others. Without convergence between various departments and agencies, the mining child falls through the gaps. All laws and policies related to mining and related processes do not address specific rights and entitlements of mining children.

“MINING HAPPINESS FOR THE PEOPLE OF ORISSA” promises one mining company. “STEEL IN EVERY STEP, SONG IN EVERY HEART” promises another. Yet why then are people affected by mining asking, “the government is telling us that this mining is going to be profitable to the country and that this is for India’s development... But if this is India’s development, are we not a part of India? Why is the government not considering us?”

Sources: 1. Mining company signboards in Orissa.

2. Person about to be displaced for lignite mining project, Barmer district, Rajasthan, July 2009.

Recommendations

Specific for children

• The government must recognise that children are impacted by mining in a number of ways, and these impacts must be considered and addressed at all stages of the mining cycle pre-mining, mining and post-mining.

• This concern for mining children must find reflection in all laws and policies on mining- National Mineral Policy 2008; the Mines and Minerals (Development and Regulation) (MMDR); Mines (Amendment) Act, 1983.

• Recognising that children concerns in the present governance structure are the responsibility of several departments in the State and Ministries in the Centre, it is essential to ensure convergence both in law and policy level, as well of services to ensure justice to the mining child.

• There is a need for linking the existing child protection institutions the National Commission for Protection of Child Rights as well as the State Commissions for Protection of Child rights with children affected by mining and the establishment of a state level and district level monitoring committee consisting of all the concerned departments that have responsibilities to protect the child responsible for monitoring as well as grievance redressal.

• The governments and society must no longer live in denial regarding the existence of children in labour in mines and amend the laws accordingly. Given the extreme hazardous nature of the activity, the Mines Act, 1952 and the Mines (Amendment) Act, 1983 must be amended to ensure that children below 18 years of age are not working in the mines as trainees and apprentices from the age of sixteen. The lacunae in the Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986 with respect to children working in mines must be addressed by amending the law to include all mining operations in Schedule A of Prohibited Occupations.17

"Swami" Style Tea Service

"Swami" Style Tea Service. Cooke & Kelvey, Calcutta, ca.1880. Sterling Silver, Dimensions: Teapot: Height: 7 1/4 inches H x 8 1/4 x 4 1/4 inches W (18.41 cm H x 21 x 10.8 cm W), Weight: 32.04 oz. (908.32 gram); Sugar Bowl: Height: 5 3/8 inches H x 4 inches W (13.65 cm H x 10.16 W), Weight: 19.11 oz. (541.75 gram); Creamer: Height: 5 3/8 inches H x 4 1/2 x 4 5/8 inches W (13.65 cm H x 11.44 x 11.75 cm W), Weight: 14.35 oz. (406.8 gram)

-- Indian Silver during the Raj, by Harish K. Patel with Veronica J. McDavid

• It is essential to mainstream child rights concerns into policies, amendments to the existing laws on mining and those that are being proposed by the respective ministries, whether with regard to the Rehabilitation Bill, the Social Security Bill, the Land Acquisition Bill, to name a few.

• Immediately address the high levels of malnourishment, hunger and food insecurity in mining areas, as has been found in this study and in keeping with the Supreme Court Orders in the Right to Food Case18 through stock taking and implementation of ICDS projects in mining areas.

• Given their especially marginalised situation, ensure that migrant, adivasi and dalit mining children receive special attention.

• Given the additional vulnerability to exploitation and abuse that mining brings to children, the government must prioritise the implementation of its flagship scheme on child protection called the Integrated Child protection Scheme (ICPS) on vulnerable areas such as the mining areas. The aim of the scheme is to reduce vulnerability as much as to provide protection to children who fall out of the social security and safety net.

• It is essential to implement the Juvenile Justice Act, 2000 to address the condition of the children in the mining areas in a manner relevant to their specific situations through the provision and strengthening of protection, monitoring and grievance redressal mechanisms or support structures for protection of mining children such as the Child Welfare Committees.

• There is need for extending the support (in a more focussed way) by the Juvenile Justice Boards, the Child Welfare Committees (CWCs) and the State Juvenile Police Units to adivasi children in areas where displacement and landlessness has led to their exploitation or brought them in conflict with law.

• Guaranteeing all mining children their right to Free and Universal Compulsory Elementary Education is a right for all children through the targeted provision of accessible and quality education, the same as that available to the children of the mining officials. Number, quality and reach of primary and elementary schools, including infrastructure and pedagogic inputs, have to be adequately scaled up.

• The National Child Labour Programme (NCLP) must be extended to all children working in mines, which means it must be upgraded substantially in terms of numbers, financial allocations and quality of delivery as well as monitoring and ensure mainstreaming of all children attending NCLP schools into regular schools is mandatory and this must be ensured from children rescued from labour in mines.

• There must be a comprehensive assessment of the health impacts on children living and working in mining areas and considering the high levels of environmental pollution and occupational diseases as a result of mining the Ministry needs to have delivery services that will address critical child health and mortality issues, especially related to pollution, contamination, toxicity, disappearance of resources like water bodies that have affected the nutrition and food security of the communities, etc.

• Rehabilitation must be an integral part of the lease agreement and the Rehabilitation Plan should clearly specify the impacts on and plans for children which must begin before the mining project begins in a time-bound manner. This includes decent and adequate housing with toilet and Potable drinking water, good quality schools within the rehabilitation/resettlement colony, electricity, anganwadi centre with supplementary nutrition to pregnant women and single mothers, colleges, health institutions, roads and transport.

• Violation of any of these impacting children should result in the cancellation of the lease. Penalties should be defined for non-implementation of rehabilitation as per projected plans and assessments with recommendations made by the monitoring committee.

Overarching Recommendations

• The Ministry of Mines has to evolve regional plans with appropriate local governance institutions (district, block) and the community with clarity in terms of quantity and quality of ore that will be extracted, the extent of area involved, demographic profile of this region, economic planning for extraction that includes number of workers required, nature of workers (local, migrant), type of technology, social cost including wages, estimate of workers and assured work period, providing (in the case of migrant workers) residential facilities like housing, basic amenities like drinking water, electricity, early childhood care facilities, quality of education, toilet, PDS facility and other requirements for a basic quality of life. The resources for these must not be drawn upon from public exchequer but recovered from the promoter.

• The public sector companies should set an example to first clean up the situation and redress the destruction caused to children and their environment in the existing mines with a clear time frame which will be scrutinised by the independent committee at regular intervals as agreed upon. The clean up should also state the budget allocated by each company for this purpose and provide details of expenditure incurred, to the committee.

• A benefit sharing mechanism must be immediately established so that it is not restricted to immediate short term monetary relief, but should show long term sustainability of the communities and workers, including post-mining land reclamation and livelihood programmes that have measurable outputs. A share from the taxes or profits shared by the companies should be ploughed into institutions for children.

• New mine leases should not be granted unless significant clean up and institutional mechanisms are in place. No private mining leases should be granted in the Scheduled Areas and the Samatha Judgement should be respected in its true spirit.

• The National Commission for the Unorganised Sector which is proposing the new Social Security Bill should take into cognizance, the above legal and policy recommendations, particularly with respect to the migrant mine workers and include adequate social security benefits that directly support development and protection of children.

_______________

Notes:

1. Centre for Science and Environment, “Rich Lands, Poor People,” State of India’s Environment: 6, 2008, pp. 3.

2. Ibid.

3. Ministry of Mines, Annual Report, 2008-2009, pp. 10.

4. U.S. Geological Survey, 2007 Minerals Yearbook: India, pp. 11.1.

5. Rediff.com, India’s GDP falls to 6.7 per cent in FY09, http://business.rediff.com/report/2009/ ... -falls.htm, 29 May, 2009.

6. Ministry for Women and Child Development, Definition of the Child, http://wcd.nic.in/crcpdf/CRC-2.PDF, uploaded: 10 August 2009.

7. Child Labour (Prohibition and Regulation) Act, 1986.

8. The worst forms of child labour comprises, inter alia, work which, by its nature or the circumstances in which it is carried out, is likely to harm the health, safety and morals of children.

9. For more information see A Handbook on UN Basic Principles and Guidelines based on Development–based Evictions and Displacement by Amnesty International India, Housing and Land Rights Network and Youth for Unity and Voluntary Action. http://www.hic-sarp.org/UN%20Handbook.pdf

10. Such as the Mines Act, 1952 (Amendment Act 1983); Mines And Minerals (Development And Regulation) Act, 1957 (As Amended Up To 20th December, 1999); Government Of India Ministry Of Mines National Mineral Policy, 2008 (For Non - Fuel And Non - Coal Minerals); as well as state polices such as Karnataka Mineral Policy 2008.

11. National Policy for Rehabilitation and Resettlement, 2007.

12. There are a number of acts and policies which specifically govern the coal industry in India. For further details, see: http://coal.nic.in/acts.htm, and http:// policies.gov.in/department.asp?id=76.

13. Mica-cutting and splitting; manufacture of slate pencils (including packing); manufacturing processes using toxic metals and substances, such as lead, mercury; fabrication workshops (ferrous and non-ferrous); gem cutting and polishing; handling chromite and manganese ores; lime kilns and lime manufacturing; stone breaking and crushing; etc.

14. In Section 21(2-iii and iv) it states that vulnerable persons such as the disabled, destitute, orphans, 14. widows, unmarried girls will be included in the survey as also families belonging to Scheduled Castes and Tribes.

15. 4 (2) “While undertaking a social impact assessment under sub-section (1), the the appropriate government shall, inter alia, take into consideration the impact that the project will have on public and community properties, assets and infrastructure; particularly, roads, public transport, drainage, sanitation, sources of drinking water, sources of water for cattle, community ponds, grazing land, plantations, public utilities, such as post offices, fair price shops, food storage godowns, electricity supply, health care facilities, schools and educational or training facilities, anganwadis, children’s parks, places of worship, land for traditional tribal institutions, burial and cremation grounds.”

16. National Commission for Protection of Child Rights, Infocus, Volume 1.No. 4

17. At present mining and collieries are the only forms of mining included in Schedule A.

18. For details see- http://www.righttofoodindia.org/icds/icds_orders.html (accessed on 13 March 2010)Interviews with mining-affected communities, Kasipur district, Orissa, June 2009.