Palestinian Artist Samia Halaby Slams Indiana University for Canceling Exhibit over Her Support for Gaza

by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

January 18, 2024

https://www.democracynow.org/2024/1/18/ ... transcript

We spend the hour looking at how artists, writers and other cultural workers in the United States and Europe are facing a growing backlash after expressing solidarity for Palestine. We begin with one of these “canceled” cultural workers: renowned Palestinian American artist Samia Halaby, whose first U.S. retrospective was canceled by her graduate alma mater, Indiana University, after she criticized Israel’s bombardment of Gaza. The school’s provost said this week the show would have been a “lightning rod” that carried a “risk of violence.” Halaby expresses her shock and disappointment at the betrayal of “academic freedom” evidenced by the decision. “The administration has lost sight of their responsibility to the community, to the students that are there,” she says, and adds, “This is much larger than I am,” citing the suppression of pro-Palestine student activism around the country and calling it “a kind of attempt at mind control.”

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Over the past three months, artists, writers and other cultural workers in the United States and Europe have faced a backlash after expressing solidarity for Palestine as Israel has continued its relentless assault on Gaza. Talks and performances have been canceled, artworks deinstalled, exhibits removed, and livelihoods threatened.

Today we speak with two Palestinian American artists. One was canceled by her own alma mater, Indiana University. The other was canceled in Berlin. And we’ll speak with a German American Jewish Holocaust survivor who stood outside the White House for months calling for a ceasefire in Gaza. She was scheduled to speak at a number of schools in her native Hamburg but was told her appearances were canceled.

We begin with Samia Halaby, a renowned Palestinian visual artist, activist, educator and scholar. Samia Halaby’s first U.S. retrospective, which had taken three years to organize, was abruptly canceled by Indiana University’s Eskenazi Museum of Art over her criticism of Israel’s bombardment of Gaza, which she has described as a genocide.

Before we speak with Samia about what happened, let’s turn to a short documentary about her life and work by Palestinian Jordanian filmmaker Munir Atalla. This is Samia talking about moving with her family to the United States as a teenager from Palestine.

SAMIA HALABY: In 1951, my father and mother had come to the decision that it was safer to bring their family up in the U.S. I did not want to come. I was 14 and close to high school. I couldn’t decide between the sciences. It was my mother who finally said, “You always loved art. Why don’t you study art?”

I gained tenure at Indiana University and decided that really I wanted to be in New York. But it’s hard to just pick up and have no money and come to New York, a city I don’t know anybody or anything in. I moved in '76. I continued trying to get a gallery for years. It was total rejection. In this world, people don't see — if you’re Palestinian, don’t see what you make. They see you. And they don’t like us Palestinians.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: This is another clip of Samia, talking about the process of creating her art and how abstraction can result from a new way of seeing.

SAMIA HALABY: I work on two, three, sometimes four or five paintings at the same time. When I enter and get going, then the paintings begin to permeate my consciousness. The paintings do not arise out of feelings. They arise out of thinking. And I am very scientific in the way I think and plan. But when I do them, I trust my intuitions —

Fulfilling every whim that comes along.

— balancing back and forth between what I intuit is right and what I want to do, and which one wins is hard to tell. When a painting is going badly, I’m feeling badly, but not because my feeling is in the painting. I’m reacting to frustration. But when it’s going well, I’m very happy, because I’ve captured something I’ve wanted to capture.

As I was saying about Palestine, something remains that I almost feel it with my hands I can make it. I put it in a painting, but it’s not a photographic image. It’s what remains visually in memory. It’s something palpable and real. What your iPhone or cellphone is telling you when you take a picture is only a teeny slice of what is in front of it when you take the picture. It’s an image of a fragment of time of reality. But the new abstraction can result from a new way of seeing.

AMY GOODMAN: An excerpt of Samia Halaby: A Video Portrait, a short documentary about the Palestinian American artist’s life and work. Samia Halaby’s paintings are in the permanent collections of the Guggenheim Museum in New York, the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., and the Art Institute of Chicago. And Samia joins us today in New York.

We welcome you to Democracy Now! We’ve told a bit of the story, but you are one of the most prestigious Palestinian American artists, in these permanent art collections around the country. You were doing this life retrospective at your alma mater, Indiana University, worked on it for three years, Samia. Can you tell us what happened right before it was to open?

SAMIA HALABY: Thank you, Amy. I’m really pleased to be with you and to tell my story and tell the story of what happened, which is very important also to the community in Bloomington and Indiana.

Just immediately before, after a lot of work preparing, first I heard a little rumble that someone was paying attention to the fact that I’m Palestinian. Other than that, I had expected, being an alumna and a one-time professor who had been awarded tenure, to be somewhat immune, because I knew the atmosphere in the country. And so, the sudden, sudden cancellation came as a surprise.

It was amazing to know that they would go ahead and act in this way, when a catalog that’s one-inch thick and hard cover had been printed and delivered, plans for the opening were being made, the artwork was picked up by the shippers. Everything was done in so beautifully and excellent museum fashion that, suddenly, after the — few days after the pickup of the paintings, I hear a very brief notice, a two-sentence letter, saying the show is canceled and the art will be returned to me. I wrote two letters suggesting, in very friendly terms, that they reverse this decision, but I have not heard a word back from them.

And, you know, Amy, this was a twin retrospective committed to my relationship to the Midwest. The Midwest had been a place where I had felt was my second home. I really enjoyed my education there. I started as I arrived in the U.S. at age 14. I’m 87 now. And I remember the University of Cincinnati with a great deal of affection for the great education we received there. I remember it being an atmosphere that was very open and radical. My teachers were all inspired by the resistant painters of the time, like Ben Shahn. They were in admiration of the industrial union movement. The Great Depression was still in people’s memory. And the professors were all very enlightened and advanced and talked a lot about academic freedom. My feeling is I wished I could bring that batch of attitudes in those professors to modern, to contemporary American education.

Maybe I’m going on too long, Amy, but my feeling, through words, what happened to me, is that the administration has lost sight of their responsibility to the community, to the students who are there. They’re trying to stop students from moving forward with thinking with their creative process politically. And that’s — they’re being more responsible to pronouncements from the government and from threats, perhaps, from parts of the government, but not at all responsible. A division is taking place in their position of having administrative power, but no responsibility to the real community.

I feel the students — the repression of the students right now in the country, who are the most advanced, the new partnership between the young Palestinians and all they’re doing and the young Jews and all that they are doing. They’re so disciplined and determined and clear-thinking. I’m really in admiration for them. And I think this act of suspension, of cancellation, is as much against them as it is against me and the curator of the show. We mustn’t forget about the curator, a curator beginning their career, to whom this was a very important show, Elliot Reichert, who was magnificent in his — as was all the staff at the museum, magnificent in their effort.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: So —

SAMIA HALABY: So I’m very — go ahead.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Samia Halaby, we’d like to get your response to the formal explanation that Indiana University, your alma mater, where you received your master’s degree — the formal response that the university gave to why your show was canceled. The university provost, Rahul Shrivastav, spoke at a faculty council meeting and addressed the backlash over the decision to cancel your show. He called your exhibit a, quote, “potential lightning rod” that could incite protests, and said the three months for it to be on view would require long-term security, adding, quote, “[If] I have to make a decision on keeping a project, a program going when there is a risk of violence or a risk of other incidents, I would err on the side of caution.” So, Samia Halaby, your response to that?

SAMIA HALABY: Well, my response to that is, first of all, they never gave me a reason, and they never responded. And they never even talked to me. So I got the impression that they didn’t like my — from a very brief phone call with the director of the museum, that, one way or the other, my general attitude and support of Palestine and criticism of Israel and U.S. partnership, U.S.-Israel attacking Palestine, and especially the massacre, the unbelievable massacre in Gaza, both destruction of people and of culture, that my anger with that and my support of the Palestinians was the cause.

I think this idea that they’re so terrorized or frightened by me being a lightning rod and the show bringing — I think the students, to their majority, were for the show. They would have been delighted to see the show. I think this idea of a lightning rod for trouble is their imagination, their invention. It’s just a propaganda, you know, invention. I don’t see the — you know, museums guard their work always, guard what is there, and they could have put a second guard on the show, if that’s — they’re so frightened. But canceling it, considering all of the grants they received, all the expenses they went through, is just not reflective of this kind of fear. Museums all over are concerned about art. So, yes, that’s my reaction to that.

You know, I would like to say some more about what’s happening in Gaza, because it connects to art. First of all, I do want to say that this is much larger than I am. There’s suppression of students throughout the U.S. There’s suppression of faculty. There’s one faculty member at Indiana University who’s been censored for — censured for a very minor thing, as an excuse for his true open-mindedness and support of young students.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to —

SAMIA HALABY: To me, the young students are —

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to go to that point, Samia. I’m looking at a piece in The Nation magazine. On December 15th, Indiana University did — suspended professor Abdulkader Sinno, “a tenured faculty member who has taught at IU for almost two decades and who, until his suspension, was the faculty adviser of the PSC. The supposed reason for the suspension: alleged mistakes in the filing of a room reservation form to support a PSC event, a scheduled public lecture by Miko Peled, an Israeli American IDF veteran and peace activist.” I mean, this is amazing. You know, Miko Peled is the son of General Peled, who, well-known in Israel, fought in 1948 and in the Six-Day War. Miko Peled was going to speak. And so, “the alleged mistakes led the administration to demand cancellation of the event two days before it was scheduled.” They went forward anyway. It proceeded without a hitch, until the administration claimed it was an unauthorized event, and the professor suspended. Samia Halaby?

SAMIA HALABY: You know, my feeling is that they indict themselves with their own words. When they suspend someone and they say the reason is he did something — made a minor mistake in filling a form requesting space for the event, it is ridiculous. You don’t suspend a professor for that kind of thing. And then you make — you create a whole range of excuses to defend the real reason. And it’s similar to my case. You know, in his case, they’re accusing him of misfilling a form. In my case, they’re saying they need — they’re worried that my show is a lightning rod to hostile activity against the show or discord among the students. So, it doesn’t make sense to me that they suspend someone who is so highly respected by the students and beloved of the students. It is unforgivable.

Again, it’s an indication that there is a huge gap growing between administrative layers and the government and the students, professors, workers, staff and general population in this country. You see it very clearly. You see huge demonstrations not only in the U.S., but all over the world, and disregard. This whole disregard of governments to what the people are asking for is, in miniature form, taking place at Indiana University. And it is this very thing I’m talking about, this division in the minds of administrators that they no longer owe anything to the students and to the faculty or to an open atmosphere of learning and discourse, as though disagreement, differences of opinion, is a negative thing. It is a kind of attempted mind control. You know, you can only think that way, and then you’re OK, and you can be a student. But if you want to discourse and see other points of view, you’re not allowed. So, it’s very backward. Very backward.

***

Artist Emily Jacir: Rampant Censorship Is Part of the Genocidal Campaign to Erase Palestinians

by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

January 18, 2024

https://www.democracynow.org/2024/1/18/ ... transcript

We speak with award-winning Palestinian American artist and filmmaker Emily Jacir, whose event in Berlin in October was canceled after Israel launched its ongoing assault on Gaza. Jacir decries a pattern of “harassment, baseless smear campaigns, canceling shows, canceling talks” conducted against Palestinian artists in Germany and around the world. “It’s very much part of a coordinated movement,” she says, connecting global censorship of diasporic Palestinian voices with the violent “targeted destruction of culture in Gaza,” which she calls a “part of genocide.”

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: Samia Halaby, we want to bring in another Palestinian American artist into this discussion, the artist and filmmaker Emily Jacir. She was scheduled to speak at any event in Berlin, Germany, in October, but her appearance was canceled. She’s the recipient of prestigious awards, including a Golden Lion at the Venice Biennale, a Prince Claus Award from the Prince Claus Fund in The Hague, the Hugo Boss Prize at the Guggenheim Museum, and most recently she won an American Academy of Arts and Letters prize and received an honorary doctorate from the National College of Art and Design in Dublin, Ireland. She is the founding director of Dar Yusuf Nasri Jacir for Art and Research in Bethlehem, where she was born.

Welcome to Democracy Now!, Emily. It’s very good to have you with us. Can you talk about what’s happened to you, actually, not here in the United States, but in Berlin, Germany?

EMILY JACIR: Thank you, Amy, for having me on your show. It’s really a pleasure to be here. I also just would like to begin by expressing my solidarity for Samia and the loss of her show, but also for the curator, Elliot, because he was in Bethlehem last summer and spoke to me at length about this exhibition, so I was quite excited about it.

I was slated to speak in Berlin as part of a workshop at Potsdam University. And when they canceled the talk, they wrote to me and said they were going to postpone it to a more peaceful time — or, to a more peaceful point in time, which, now listening to Samia speaking about the idea of being a lightning rod, this really resonated with me. And this is one of the methodologies that is being used to actually stop us from being able to speak publicly and share our words and share our work. This is another way of doing it, is by saying, “Oh, we’ll just do this in another peaceful time.” But this is the time. This is the time when we should be speaking and having discourse, across the board, around the world. So I don’t buy that that was the real reason.

Again, we have to also take the curator into consideration and try to imagine what kind of pressure, particularly being in Germany, they must have been under. The situation in Germany, as we all know, is one of the most extreme cases of silencing Palestinians. But it’s part of a larger war effort targeting Palestinian voices and intellectuals, using various methodologies, including harassment, baseless smear campaigns, canceling shows, canceling talks. So, it’s very much part of a coordinated movement.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: So, Emily Jacir, could you talk about some of the — there have been numerous incidents in Germany where people have been canceled, for one reason or another having to do with Gaza. If you could just go through some of those people, in particular, the Palestinian artists and writers?

EMILY JACIR: Yeah, I mean, I think one of the first incidents was Adania Shibli, who was slated to receive an award in Germany. That was within the first week of October, if I remember correctly. The list is quite extensive. My sister’s film, Annemarie Jacir, was canceled within weeks also, I think. Her film was canceled. It’s a film about a wedding, and it was deemed too controversial to show on German television. Candice Breitz, as we all know, is another person. There are so many. The list is endless.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: Well, we want to go now to a writer, a highly acclaimed writer and author, the award-winning Masha Gessen, who was also canceled, or her award. She was to receive the Hannah Arendt Award in Bremen. We spoke to her in December, shortly after the publication of their New Yorker piece headlined “In the Shadow of the Holocaust: How the politics of memory in Europe obscures what we see in Israel and Gaza today.”

In the essay, Gessen wrote, quote, “For the last seventeen years, Gaza has been a hyperdensely populated, impoverished, walled-in compound where only a small fraction of the population had the right to leave for even a short amount of time — in other words, a ghetto. Not like the Jewish ghetto in Venice or an inner-city ghetto in America but like a Jewish ghetto in an Eastern European country occupied by Nazi Germany,” they wrote.

Gessen went on to explain why the term “ghetto” is not commonly used to describe Gaza. Gessen said, quote, “Presumably, the more fitting term 'ghetto' would have drawn fire for comparing the predicament of besieged Gazans to that of ghettoized Jews. It also would have given us the language to describe what is happening in Gaza now. The ghetto is being liquidated,” Gessen wrote.

They had been scheduled to receive the prestigious Hannah Arendt Prize in Germany, but the ceremony had to be postponed after one of the award’s sponsors, the left-leaning Heinrich Böll Foundation, withdrew its support.

Gessen discussed the New Yorker piece and the controversy that followed on Democracy Now! on the very day they had been originally scheduled to receive the award in Bremen.

MASHA GESSEN: A large part of the article is devoted to, in fact, memory politics in Germany and the vast anti-antisemitism machine, which largely targets people who are critical of Israel and, in fact, are often Jewish. This happens to be a description that fits me, as well. I am Jewish. I come from a family that includes Holocaust survivors. I grew up in the Soviet Union very much in the shadow of the Holocaust. That’s where the phrase in the headline came from, is from the passage in the article itself. And I am critical of Israel.

Now, the part that really offended the Heinrich Böll Foundation and the city of Bremen — and, I would imagine, some German public — is the part that you read out loud, which is where I make the comparison between the besieged Gaza, so Gaza before October 7th, and a Jewish ghetto in Nazi-occupied Europe. I made that comparison intentionally. It was not what they call here a provocation. It was very much the point of the piece, because I think that the way that memory politics function now in Europe and in the United States, but particularly in Germany, is that their cornerstone is that you can’t compare the Holocaust to anything. It is a singular event that stands outside of history.

My argument is that in order to learn from history, we have to compare. Like, that actually has to be a constant exercise. We are not better people or smarter people or more educated people than the people who lived 90 years ago. The only thing that makes us different from those people is that in their imagination the Holocaust didn’t yet exist and in ours it does. We know that it’s possible. And the way to prevent it is to be vigilant, in the way that Hannah Arendt, in fact, and other Jewish thinkers who survived the Holocaust were vigilant and were — there was an entire conversation, especially in the first two decades after World War II, in which they really talked about how to recognize the signs of sliding into the darkness.

And I think that we need to — oh, and one other thing that I want to say is that our entire framework of international humanitarian law is essentially based — it all comes out of the Holocaust, as does the concept of genocide. And I argue that that framework is based on the assumption that you’re always looking at war, at conflict, at violence through the prism of the Holocaust. You always have to be asking the question of whether crimes against humanity, the definitions of which came out of the Holocaust, are occurring. And Israel has waged an incredibly successful campaign at setting — not only setting the Holocaust outside of history, but setting itself aside from the optics of international humanitarian law, in part by weaponizing the politics of memory and the politics of the Holocaust.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Masha Gessen. Masha Gessen was speaking to us from Bremen, Germany. The award ceremony went from an auditorium of hundreds — they ultimately got the award in someone’s backyard.

Meanwhile, more than 500 global artists, filmmakers and writers and cultural workers have announced a push against Germany’s stance on Israel’s war on Gaza, calling on artists to step back from collaborating with German state-funded associations. The campaign is backed by the French author, Nobel Prize for Literature winner Annie Ernaux and the Palestinian poet and activist Mohammed el-Kurd. It alleges Germany has adopted, quote, “McCarthyist policies that suppress freedom of expression, specifically expressions of solidarity with Palestine,” unquote.

We’re speaking with Emily Jacir, whose speech was just canceled in Berlin, Germany. And as we wrap up with you, Emily, I wanted to know if you could comment on what’s happening in your birthplace, in Bethlehem. The last time we went to Bethlehem, we were interviewing two pastors there, one of them who set up Christ in the rubble, a crèche scene that showed the baby Jesus in rubble, signifying Gaza. If you can talk about that and the importance of your art, as you continue?

EMILY JACIR: Yeah, I will talk about that, but just to relate back to what everyone else was talking about and how you started, I think it’s really important to consider the way this attempt at creating a culture of fear amongst the arts community globally and internationally is happening through these baseless smear campaigns and defamation, threatening people’s jobs. And I mention this just because, you know, one of the things that happened to me was that there was a letter-writing campaign in which every university I’ve ever taught at internationally, anyone that’s ever given me an award received literally a five-page PDF claiming that I was an ISIS terrorist that supports the rape of women and the killing of babies. People who signed that Artforum letter, and many, many, many of whom are Jewish and Israeli allies that I have worked with for 25 years, also received that letter. In my case, because people know me — they’ve worked with me for 25 years — the letters come off as just absolutely absurd and ridiculous. But if that is happening to me, it begs the question of what is happening to younger artists, people who don’t — people in museums don’t know receiving letters like that. And it’s very targeted and very systematic, and it’s something to consider also in relationship with the targeted destruction of culture in Gaza, art centers being bombed. Why would an art center be bombed? Because part of genocide is precisely silencing artists and silencing a culture’s cultural production. And I feel that that was very important to say that.

In Bethlehem, the situation is quite difficult — nothing compared to Gaza, of course. But we are witnessing incursions every night. It’s been — you know, Bethlehem is a town that very, very much relies on visitors and tourists for its economy, so that, economically, it’s been a disaster. As an art center, our art center in Bethlehem promotes dance and music and art practices and making and residencies of local artists and international artists. We’re doing our very best to both deal with the situation at hand but also provide a kind of way of working with the children now who live in our neighborhood who are trying to handle the situation, both on the ground in Bethlehem but also witnessing what’s happening to Gaza.

AMY GOODMAN: Emily Jacir, we want to thank you for being with us, acclaimed artist and filmmaker, born in Bethlehem, goes back and forth between Bethlehem and New York, was scheduled to speak in Berlin, Germany, her talk canceled. And Samia Halaby, renowned Palestinian visual artist, activist, educator and scholar, whose first U.S. retrospective was abruptly canceled by Indiana University’s Eskenazi Museum of Art over her support for Palestinians and criticism of Israel’s bombardment of Gaza.

**

Holocaust Survivor Marione Ingram Decries Climate of Censorship After Her Hamburg Talks Are Canceled

by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

January 18, 2024

https://www.democracynow.org/shows/2024/1/18

We are joined by 88-year-old Jewish German American Marione Ingram, who describes how her scheduled speaking tour in Hamburg — the city she fled in the Holocaust — was “postponed” this month amid a wider backlash against those speaking out against Israel’s assault on Gaza. Ingram has been protesting for months outside the White House calling for a ceasefire, and characterizes U.S. and German pro-Israel policy as “disturbing” and “frightening.” As a survivor of the Holocaust, Ingram says, “My childhood was spent in the first 10 years much the same way as the children of Gaza. I know exactly what they’re going through. I know exactly how they’re feeling.” She argues “it should be an absolute standstill of all governments that you are told over 10,000 children are being murdered. There is no excuse for that.”

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman, with Nermeen Shaikh.

NERMEEN SHAIKH: We turn now to Marione Ingram. She’s an 88-year-old German American Holocaust survivor who’s been protesting for months outside the White House calling for a ceasefire in Gaza. She was scheduled to speak this month at eight different schools in her native Hamburg, Germany. She was planning to address students receiving awards recognizing their commitment to social justice activism. Then, in December, she was told by an event organizer that her appearances were canceled. The trip was eventually postponed until May.

AMY GOODMAN: Marione Ingram is author of The Hands of War: A Tale of Endurance and Hope from a Survivor of the Holocaust and also the book The Hands of Peace: A Holocaust Survivor’s Fight for Civil Rights in the American South. She’s joining us from Washington, D.C.

Marione, I’m sorry you had to leave the studio because there was an alarm in the building and everyone had to evacuate, but you’re back now. And you have heard the previous guests, two Palestinian American esteemed artists, talking about having been canceled, like you, Samia Halaby by Indiana University, and Emily Jacir was about to give a talk in Berlin. Talk about the reason you were given for going back to Hamburg, Germany, where you’ve gone a number of times to speak to young people, but the reason why your talks were canceled this month.

MARIONE INGRAM: Good morning, Amy. Yes, a bit of excitement, so I missed — I heard Samia’s explanation of her cancellation — I’m really sorry about that — and missed the other, because we were evacuated.

The reasons for my cancellation have been extremely vague, given a climate in Germany right now of a lot of antisemitic events, apparently. And the only concrete explanation I got from someone was that I, as a Holocaust survivor, would be used by the AfD, which is the Alternative for Deutschland, the Alternative for Germany, which is a neo-Nazi and a primarily antisemitic group. But I was told that they would use my picture and my protest sign in a propaganda — I can’t even figure out what kind of propaganda that would be used for, since they are basically Nazis and would be a destruction of —

AMY GOODMAN: The sign you’re talking about is, standing outside the White House, “Survivor says peace not war”?

MARIONE INGRAM: Yes, yes. But on the flip side, it says “Stop genocide in Gaza.” And that has upset the powers that be, politicians who decide what can be said and what cannot be said.

I have been speaking to students for years, and I was also told by several teachers that right now my presence, talking to students, is of the utmost importance, because the schools in Hamburg are so diverse and there are many students who come from countries where there is war, oppression, poverty, and students in really terrible positions of trying to manage what is going on, conflict with each other. And I was told that my presence is so important because I have a rapport with students, and they were looking forward to expressing their thoughts, because they know that in talking to me and with me that they can say everything that is on their minds without being criticized or ostracized.

I find it extremely — I understand Germany’s sensitivity because of their gruesome history. But Germany has also been the only country, maybe other than Rwanda, that has acknowledged its horrific history, and it has taught this history as a “never again” thing. We must face our history so we can learn from it. So it is surprising to me that Germany has chosen to silence me.

But I think the worst part of it is that they are silencing young people who are experiencing — especially in Germany, they are close to the war in Ukraine. They are troubled by what is going on by the war in the Mideast and the horrific slaughter of innocent people. It should be an absolute standstill of all governments when you are told that over 10,000 children are being murdered. There is no excuse for that.

And then to turn around — America and Germany’s support of Israel’s politics is extremely disturbing and, to me, frightening, because any time any government decides to silence the voices of people who oppose government policies, whatever they may be, this reminds me so much of my childhood. My childhood was spent in the first 10 years much the same way as the children of Gaza. I know exactly what they are going through. I know exactly what they are thinking. And this, apparently, has upset the Ministry of Culture, because I have compared the onset —

AMY GOODMAN: We have less than a minute to go.

MARIONE INGRAM: The silencing of the last survivor of all three major events in Hamburg — the firestorm, the worst bombing in the European war, and the Holocaust, where I lost almost all of my family — and the silencing of voices like all of our voices when they are most needed is indicative of something more frightening, because I believe when governments decide to silence voices in opposition to the stance that they are taking, then we have to really question very deeply why are they doing it and for what reason.

AMY GOODMAN: Marione Ingram, we’re going to have to leave it there, but we thank you so much for being with us, 88-year-old Jewish German Holocaust survivor, has been protesting, calling for Biden to support a Gaza ceasefire.

U.S. Backing Has Given Israel License to Kill & Maim

Re: U.S. Backing Has Given Israel License to Kill & Maim

Meet Tal Mitnick, 18, the First Israeli Jailed for Refusing Military Service in “Revenge War” on Gaza

by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

January 19, 2024

https://www.democracynow.org/2024/1/19/ ... transcript

As Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu vows to continue the assault on Gaza, we speak with the first Israeli to refuse mandatory military service since Israel’s offensive began over three months ago. Last month, 18-year-old Tal Mitnick announced he would refuse military service in what he called a “revenge war” on Gaza, and was sentenced to 30 days in a military prison. Just released from jail, Mitnick faces another draft summons and says he will refuse “over and over until someone gives up, until the army gives me an exemption.” Mitnick says the October 7 Hamas attack on southern Israel broke the idea Israel could live with occupation. “We need to keep fighting for a just future,” he says, urging the younger generation of Israelis to use their voices for peace. “We’re the future, and we can change.”

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

Israel is continuing its attacks across the Gaza Strip, from the north to the south, as the number of Palestinian casualties continues to soar. Over the last 24 hours, at least 142 Palestinians were killed in Gaza, according to the Palestinian Health Ministry. Nearly 25,000 Palestinians have been killed over the past three months, 10,000 of them children, thousands of others missing under the rubble presumed dead, making Israel’s assault one of the deadliest, most destructive military campaigns in recent history.

Meanwhile, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has again rejected calls to scale back Israel’s military assault on Gaza or take steps towards the establishment of a Palestinian state. In a nationally broadcast news conference, Netanyahu vowed to press ahead with the offensive until what he called a “decisive victory over Hamas.”

As Netanyahu vows to continue Israel’s assault on Gaza, we turn now to the first Israeli to refuse mandatory military service since Israel’s offensive began over three months ago. Tal Mitnick is an 18-year-old conscientious objector in Israel. Last month, he announced he would refuse military service, saying, quote, “I refuse to take part in a war of revenge.” He was sentenced to 30 days in a military prison, was just released yesterday morning. Tal Mitnick is joining us now from a studio in Tel Aviv.

Tal, welcome to Democracy Now! Can you talk about why you are refusing?

TAL MITNICK: Thank you for having me on.

I am refusing because, like I said, I refuse to take part in this revenge war. I’m refusing because I want to make a statement about how we need to conduct ourselves in this land. I feel like there’s too much violence here. There’s too much revenge and talk about this side or that side. And we need to talk about how we need to go forward in a future of coexistence, where both Israelis and Palestinians can live together and live with security and peace.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about what exactly this means. How did you make this known? Talk about where you served time in prison. And is this just a brief period of days before you’re sent back to prison?

TAL MITNICK: Yes. I got sentenced for 30 days for my first sentencing, and I got another draft order for Monday morning, which means I have to get drafted on Monday morning, where I will go and refuse service once again and probably get sentenced again. And this will happen over and over until someone gives up, until the army gives me an exemption.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about the response of your friends, your family. And I was also just wondering — you’re an Israeli, but you have an American accent. Are you American, as well?

TAL MITNICK: My parents immigrated from the U.S., and we spoke English at home. But I’m Israeli and American, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: So —

TAL MITNICK: The friends and family response — yes?

AMY GOODMAN: Go ahead.

TAL MITNICK: My friends and family response was, thankfully, mostly very understanding, because people that know me and people that talk to me know that I come from a good place of nonviolence and coexistence. I feel like the people that got to talk to me also inside military prison, a lot of them, Ben-Gvir supporters, they support killing all Arabs. When they got to know me before they knew my political opinions, they understood. They understood that there are people that don’t support this. Sorry, I can hear myself twice.

AMY GOODMAN: If you can possibly blank that out, because we’re not sure how to fix that right now. But just continue to talk, because we don’t hear you twice, but we do hear you very clearly.

TAL MITNICK: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about your time —

TAL MITNICK: OK, yeah. So, the —

AMY GOODMAN: — in prison? And where are you —

TAL MITNICK: No, no, go ahead.

AMY GOODMAN: — being held?

TAL MITNICK: Yeah. So, I’m being held in a military prison, where other soldiers that have committed crimes inside the military and got sentenced to military prison are also being held. It’s not a fun experience, but it’s also not the worst experience imaginable. It’s not like the experience that Palestinian prisoners are being held under in the West Bank or inside Israel. Yeah, it’s very strict timing, very strict about what you’re allowed to do and when. But this is something that I’m willing to do to make an impact.

AMY GOODMAN: I’m wondering if you feel the climate is changing among Israelis, and also what Israelis see about what’s happening in Gaza. I mean, we just reported we’re talking about now close to 25,000 Palestinians killed, over 10,000 children, over 7,000 women, many believed to be dead in the rubble. We don’t even know that count. If you watch something like Al Jazeera or you watch other media, since there are only Palestinian journalists there on the ground, you see endless pictures of carnage, of horror, of babies being pulled out of the rubble, dead or alive. What do you see on Israeli TV? We’re talking about people who are just 15 minutes away from Gaza.

TAL MITNICK: So, actually, inside prison, the only source of news that we got was one newspaper called Israel Hayom. And every day on the newspaper, there will be pictures of the soldiers that died. And I remember feeling like — I feel sad, very sad for the soldiers and the families that have to take this great burden of losing someone close to them, but I know that while seeing soldiers dying, I know that this means that there are much more Palestinian civilians dying, which we don’t see in the newspaper.

AMY GOODMAN: Who else are you serving time with in that prison? Who else is there?

TAL MITNICK: Sadly, a lot of the other people there don’t — they are deserters, which means that they served time in the military, and then at some point, for some reason, they went back home and did not come back. Most of these people desert because of socioeconomic reasons, if it’s having to take care of their siblings or go work for their family. And when they come back and turn themselves in, we’re now seeing a very heavy sentencing of those deserters as a part of the fascist persecution and the fog of war. People that went to work for three months to feed their family are now being sentenced to half a year in military prison.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the overall antiwar movement, if there is one in Israel? I mean, there were massive protests, up to a million people in the streets, which is massive for Israel, around the — Netanyahu wanting to gut the power of the judiciary. Of course, he is under charges himself, and that would help him remain out of prison. But at that point, many reservists said they would not serve in the military. Everything changed after October 7th Hamas attack on southern Israel. If you can talk about why that did not change you? And how large is the antiwar movement, and do you feel it’s growing?

TAL MITNICK: I feel like after the horrendous attack of October 7th against Israeli civilians, there was a very important conception that was broken in Israeli society: the conception that we can live with the siege and with the occupation and not feel it. Now, when that conception is broken, we have a vacuum. And there are two ideas that are trying to pull people: one idea that the right is offering, which is, “We can’t live with occupation. We can’t live with siege. This means we need to wipe all of them out,” and the other idea, the moderate one, the one that makes sense, is that “We can’t live with occupation. We can’t live with siege. We need to step forward for peace.”

Inside military prison, I got asked a lot, “What do you think? We should just stop the war and put our hands up and not do anything?” And I would answer, “No, we need to keep fighting. We need to keep fighting for a just future. We need to stop the physical fighting between us, and we need to very, very aggressively push for a better future.”

AMY GOODMAN: I’m wondering your response to Prime Minister Netanyahu once again saying “from the river to the sea.” When Palestinian advocates and their allies talk about “from the river to the sea,” the response of the Israeli government has been, “That means they’re for the genocide of Jews, because they don’t want Jews to be there,” the government says. Now you have Netanyahu saying — not that this hasn’t been said before by Likud — but, “From the river to the sea, Israel must control.” Your response to that, Tal? And if you can talk about the word “occupation”? Because in the U.S. media also, there is rarely that word used, that Israel occupies the West Bank and Gaza.

TAL MITNICK: The term “from the river to the sea” is very controversial inside of Israel. And I feel like some people that use it, there are people that use it that mean the genocide of Jews inside Israel. But just the term itself, I feel like, does not mean a genocide of Jews; it means freedom of all Palestinians from the river to the sea. When Benjamin Netanyahu uses this term, it does not mean freedom for all from the river to the sea; it means oppression of Palestinians, and it means Jewish supremacy from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, Tal, I’m wondering your response to Jews around the world, particularly here in the United States, like Jewish Voice for Peace, these massive protests that have been held, from Grand Central Station to shutting down the bridges and the tunnels from New York, to highways in California, saying, “We want a ceasefire now.” How do you respond to that? And your final message to other 18-year-old Israelis?

TAL MITNICK: These protests are amazing. These organizations, like Jewish Voices for Peace and IfNotNow, do incredible work. And I support the continuation of these protests all around the world.

And a message to other people my age, other kids, I feel like it’s important to know that we have a voice. I used to think that talking to people is all we could do, but we can change, and people want to hear what we have to say because we’re the future. And this is — yeah, we’re the future, and we can change.

AMY GOODMAN: And finally, might you spend months, more than a year in jail if you keep saying no to military service, since Netanyahu says this will go on for more than a year?

TAL MITNICK: Because there’s no policy set for jailing conscientious objectors, I don’t really know how much time I’ll spend in prison, but it could be months.

AMY GOODMAN: Tal Mitnick, 18-year-old Israeli activist, known as a refusenik. He’s refused mandatory military service in the Israeli army, the first conscientious objector in Israel since the Israeli assault on Gaza began over a hundred days ago. He’s just sentenced to 30 days in prison, which he served, for refusing to enlist, was released a few days ago, then will be called up again and says he will refuse again.

***

Horrific Traumatic Injuries of Children: British Dr. Witnesses Israel’s Destruction of Gaza Hospitals

by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

January 19, 2024

https://www.democracynow.org/2024/1/19/ ... transcript

Before Israel’s unprecedented assault on Gaza, the territory had 36 functioning hospitals. Now only 16 partially functioning health facilities remain. As Israeli bombs and ground troops approach Nasser Hospital, the largest remaining partially functioning health facility in Gaza, we speak with Dr. James Smith, an emergency medical doctor recently returned from Gaza, where he worked alongside Palestinian healthcare workers to treat patients at Al-Aqsa Hospital. “Every single day, without exception, there were multiple mass casualty incidents at the hospital,” says Smith. “They would include open chest wounds, open abdominal wounds, traumatic amputations, severe full-thickness burns … really some of the most horrific traumatic injuries that I have ever seen.”

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

Israeli forces are pushing further into southern Gaza, with airstrikes and ground troops attacking areas that Israel had previously told Palestinians to flee to as safe zones. Over the past few days, Israel has bombed areas close to Nasser Hospital, the largest remaining semi-functioning health facility in Gaza, located in the southern city of Khan Younis. Gaza only has 16 partially functioning health facilities remaining. Before Israel’s assault, Gaza had 36 hospitals. The hospitals that are still working are operating far beyond their capacity, have been turned into makeshift refugee camps to house the displaced — and makeshift morgues — with health officials describing the situation as catastrophic. The Health Ministry estimates that over 60,000 people have been wounded in Gaza, with hundreds more casualties every day. The casualty count at this point is nearing 25,000, more than 10,000 of them children.

For more, we’re joined by Dr. James Smith, an emergency medical doctor who just returned from Gaza earlier this month, where he worked alongside Palestinian healthcare workers to treat patients at Al-Aqsa Hospital located in Deir al-Balah in the middle of the Gaza Strip. Dr. James was in Gaza with the organization Medical Aid for Palestinians. He’s joining us now from London.

Dr. James, welcome to Democracy Now! Describe what you saw, what you confronted, the work you were doing, what’s happening at Al-Aqsa Hospital.

DR. JAMES SMITH: Hi, Amy.

So, yes, as you say, I was working with a team. There were 10 of us. Myself, I was with the organization Medical Aid for Palestinians. We were accompanied by colleagues from the International Rescue Committee. And very importantly, we were — it’s important to really reiterate that we were working with our Palestinian colleagues, so doctors, nurses, other healthcare professionals, at Al — sorry, at Al-Aqsa Hospital. Al-Aqsa is a hospital based in the middle area of Gaza, so south of Gaza City and north of Khan Younis.

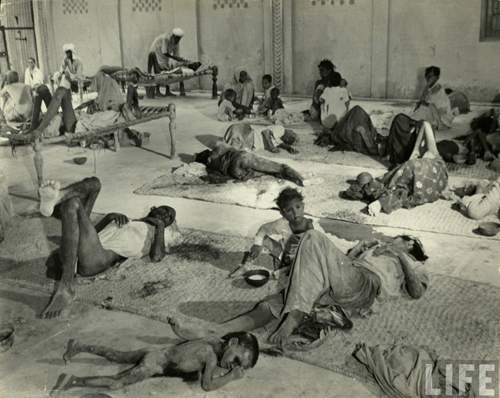

Myself, I was working in the emergency room. So, we would position ourselves in the ER every morning and, really, at that point, wait to see what the day would bring. Every single day, without exception, there were multiple mass casualty incidents at the hospital. So that’s several patients presenting at a time with traumatic injuries of varying severity. Those patients would require stabilization and then often transfer through to the operating room for surgical intervention. Some patients would require palliative care, if we were able to provide some form of palliative care, and in addition to many, many trauma patients. And by “many,” I mean several hundred over the time that we were working at Al-Aqsa. We were also treating patients presenting with complex medical problems, so people that had suffered heart attacks, for example, had suffered from strokes, and people whose hypertension or diabetes management had been negatively impacted, usually through a lack of access to their usual medication or because they hadn’t been able to see their usual doctor for several months. And then, furthermore, we were also seeing an even greater number of people with, effectively, primary healthcare-level problems.

So, the entirety of the primary healthcare or community care system in Gaza has completely collapsed. In fact, the entire healthcare system, the Ministry of Health has already announced several months ago, has completely collapsed. But that meant that anyone presenting with so-called, well, more minor complaints — coughs, colds, diarrheal illnesses — they were all also presenting to the emergency room to be seen by the doctors and nurses there.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about treating children, Dr. James?

DR. JAMES SMITH: Sure. So, as you’ve mentioned, a significant proportion of the people that have been killed since the start of this escalation are children. We certainly saw every mass casualty incident in the emergency room. There were several children also present. I remember very vividly some of the most traumatic injuries inflicted upon people were inflicted upon children. And they would include open chest wounds, open abdominal wounds, traumatic amputations, severe full-thickness burns to a substantial proportion of the body area — really some of the most horrific traumatic injuries that I have ever seen.

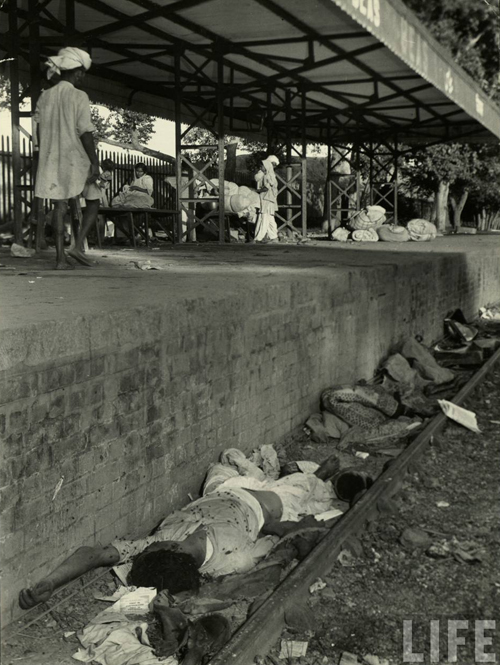

AMY GOODMAN: We’re actually showing images for our TV audience of Al-Aqsa Hospital and of the children and the adults who have been wounded there. You know, it’s really important to point out, if you’re talking about a hospital in normal times that has repeatedly been attacked, it would — and that’s severely compromised in its functioning, but we’re talking about this constant bombardment, where you have people coming in who have been severely wounded. You have people taking refuge there. And is it both like a refugee camp and a morgue?

DR. JAMES SMITH: So, there were several thousand people that had sought supposed sanctuary within the hospital compound itself. And we’ve seen this in several other hospitals across the Gaza Strip. There were reports, for example, of thousands of people sheltering in the Al-Shifa compound before that was surrounded and raided by the Israeli occupation forces. The same was the case at Al-Aqsa. So there were people staying in makeshift tents in and around the hospital buildings. Just up the main street adjacent to the hospital, sort of another IDP camp, internally displaced persons camp, had sort of formed very organically on open land. As the Israeli ground forces moved closer to the hospital and as the bombardment, the artillery and air bombardment, intensified, many of those — many thousands of those displaced people have displaced further south towards Rafah. And that also includes patients who were in the hospital at the time that we were working there. Many of them have also fled, along with many of the staff, as well.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to go to a clip, and it’s really important to play these clips. Right now Gaza has experienced the longest communications blackout of this Israeli attack for the last three months. I think it’s something like seven days. So it’s really hard to get information inside this intense Israeli bombardment in the vicinity of Nasser Hospital, the main hospital in Khan Younis, the largest remaining semi-functioning health facility in Gaza, and tanks and armored vehicles are on the main road leading to the area. On Wednesday, Democracy Now! reached Dr. Ahmed Moghrabi, who works in Nasser Hospital. He described the situation on the ground and the difficulty in getting out any messages. This is what he had to say.

DR. AHMED MOGHRABI: Thank you, sister, for asking about us. Thank you for letting me speak out here. We don’t have internet at all. I managed to get a very weak signal. I can’t upload any of these videos. Here, 90% of people who are already evacuated at the hospital, they evacuated from the hospital. Ninety percent of medical personnel evacuated from the hospital.

And this is my little daughter, actually. She got head trauma Saturday. You know, hundreds of these evacuating people at the corridor, somebody pushed her, and she fell on her head. Now I’m taking care about my — this little girl. She needs medicine. She’s not well. So I stay at the hospital now, but I want to evacuate. The situation is catastrophic, sister. Really, I’m very tired. I’m very tired.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Dr. Ahmed Moghrabi, and the image we’ve been showing as he spoke was Dr. Moghrabi holding his own wounded daughter. I’m wondering, Dr. James, if you can talk about the significance, the medical significance, of a complete — almost complete telecommunications blackout, in terms of ambulances being reached, people being able to communicate to get help.

DR. JAMES SMITH: Absolutely. I mean, this is a catastrophic development. As you’ve mentioned, Amy, this, I think, is the seventh time that the Israelis have suspended access to telecommunications across almost the entirety of the Gaza Strip. This is now day six or seven of a complete sort of telecommunications blackout. It makes it almost impossible to do anything.

So, in the first instance, people can’t reach their families, their loved ones. They can’t communicate with colleagues. They can’t reassure family that they’re OK, or indeed relatives and friends can’t inform family members and so on when somebody has been killed or injured. There have been occasions where the emergency number has not been in use. So, as you say, it’s been difficult to call ambulances or mobilize ambulances to places where there has been an air or artillery strike. It makes it very difficult for health and humanitarian workers to do their essential work —

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Smith, we —

DR. JAMES SMITH: — so they can’t coordinate with each other.

AMY GOODMAN: We only have 10 seconds. What message do you have for the world, just having come out of Gaza? Ten seconds.

DR. JAMES SMITH: The violence needs to end immediately.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. James Smith, emergency medical doctor, just back from Gaza, where he worked to treat patients at Al-Aqsa Hospital.

by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

January 19, 2024

https://www.democracynow.org/2024/1/19/ ... transcript

As Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu vows to continue the assault on Gaza, we speak with the first Israeli to refuse mandatory military service since Israel’s offensive began over three months ago. Last month, 18-year-old Tal Mitnick announced he would refuse military service in what he called a “revenge war” on Gaza, and was sentenced to 30 days in a military prison. Just released from jail, Mitnick faces another draft summons and says he will refuse “over and over until someone gives up, until the army gives me an exemption.” Mitnick says the October 7 Hamas attack on southern Israel broke the idea Israel could live with occupation. “We need to keep fighting for a just future,” he says, urging the younger generation of Israelis to use their voices for peace. “We’re the future, and we can change.”

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

Israel is continuing its attacks across the Gaza Strip, from the north to the south, as the number of Palestinian casualties continues to soar. Over the last 24 hours, at least 142 Palestinians were killed in Gaza, according to the Palestinian Health Ministry. Nearly 25,000 Palestinians have been killed over the past three months, 10,000 of them children, thousands of others missing under the rubble presumed dead, making Israel’s assault one of the deadliest, most destructive military campaigns in recent history.

Meanwhile, Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has again rejected calls to scale back Israel’s military assault on Gaza or take steps towards the establishment of a Palestinian state. In a nationally broadcast news conference, Netanyahu vowed to press ahead with the offensive until what he called a “decisive victory over Hamas.”

As Netanyahu vows to continue Israel’s assault on Gaza, we turn now to the first Israeli to refuse mandatory military service since Israel’s offensive began over three months ago. Tal Mitnick is an 18-year-old conscientious objector in Israel. Last month, he announced he would refuse military service, saying, quote, “I refuse to take part in a war of revenge.” He was sentenced to 30 days in a military prison, was just released yesterday morning. Tal Mitnick is joining us now from a studio in Tel Aviv.

Tal, welcome to Democracy Now! Can you talk about why you are refusing?

TAL MITNICK: Thank you for having me on.

I am refusing because, like I said, I refuse to take part in this revenge war. I’m refusing because I want to make a statement about how we need to conduct ourselves in this land. I feel like there’s too much violence here. There’s too much revenge and talk about this side or that side. And we need to talk about how we need to go forward in a future of coexistence, where both Israelis and Palestinians can live together and live with security and peace.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about what exactly this means. How did you make this known? Talk about where you served time in prison. And is this just a brief period of days before you’re sent back to prison?

TAL MITNICK: Yes. I got sentenced for 30 days for my first sentencing, and I got another draft order for Monday morning, which means I have to get drafted on Monday morning, where I will go and refuse service once again and probably get sentenced again. And this will happen over and over until someone gives up, until the army gives me an exemption.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about the response of your friends, your family. And I was also just wondering — you’re an Israeli, but you have an American accent. Are you American, as well?

TAL MITNICK: My parents immigrated from the U.S., and we spoke English at home. But I’m Israeli and American, yes.

AMY GOODMAN: So —

TAL MITNICK: The friends and family response — yes?

AMY GOODMAN: Go ahead.

TAL MITNICK: My friends and family response was, thankfully, mostly very understanding, because people that know me and people that talk to me know that I come from a good place of nonviolence and coexistence. I feel like the people that got to talk to me also inside military prison, a lot of them, Ben-Gvir supporters, they support killing all Arabs. When they got to know me before they knew my political opinions, they understood. They understood that there are people that don’t support this. Sorry, I can hear myself twice.

AMY GOODMAN: If you can possibly blank that out, because we’re not sure how to fix that right now. But just continue to talk, because we don’t hear you twice, but we do hear you very clearly.

TAL MITNICK: Yes.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about your time —

TAL MITNICK: OK, yeah. So, the —

AMY GOODMAN: — in prison? And where are you —

TAL MITNICK: No, no, go ahead.

AMY GOODMAN: — being held?

TAL MITNICK: Yeah. So, I’m being held in a military prison, where other soldiers that have committed crimes inside the military and got sentenced to military prison are also being held. It’s not a fun experience, but it’s also not the worst experience imaginable. It’s not like the experience that Palestinian prisoners are being held under in the West Bank or inside Israel. Yeah, it’s very strict timing, very strict about what you’re allowed to do and when. But this is something that I’m willing to do to make an impact.

AMY GOODMAN: I’m wondering if you feel the climate is changing among Israelis, and also what Israelis see about what’s happening in Gaza. I mean, we just reported we’re talking about now close to 25,000 Palestinians killed, over 10,000 children, over 7,000 women, many believed to be dead in the rubble. We don’t even know that count. If you watch something like Al Jazeera or you watch other media, since there are only Palestinian journalists there on the ground, you see endless pictures of carnage, of horror, of babies being pulled out of the rubble, dead or alive. What do you see on Israeli TV? We’re talking about people who are just 15 minutes away from Gaza.

TAL MITNICK: So, actually, inside prison, the only source of news that we got was one newspaper called Israel Hayom. And every day on the newspaper, there will be pictures of the soldiers that died. And I remember feeling like — I feel sad, very sad for the soldiers and the families that have to take this great burden of losing someone close to them, but I know that while seeing soldiers dying, I know that this means that there are much more Palestinian civilians dying, which we don’t see in the newspaper.

AMY GOODMAN: Who else are you serving time with in that prison? Who else is there?

TAL MITNICK: Sadly, a lot of the other people there don’t — they are deserters, which means that they served time in the military, and then at some point, for some reason, they went back home and did not come back. Most of these people desert because of socioeconomic reasons, if it’s having to take care of their siblings or go work for their family. And when they come back and turn themselves in, we’re now seeing a very heavy sentencing of those deserters as a part of the fascist persecution and the fog of war. People that went to work for three months to feed their family are now being sentenced to half a year in military prison.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about the overall antiwar movement, if there is one in Israel? I mean, there were massive protests, up to a million people in the streets, which is massive for Israel, around the — Netanyahu wanting to gut the power of the judiciary. Of course, he is under charges himself, and that would help him remain out of prison. But at that point, many reservists said they would not serve in the military. Everything changed after October 7th Hamas attack on southern Israel. If you can talk about why that did not change you? And how large is the antiwar movement, and do you feel it’s growing?

TAL MITNICK: I feel like after the horrendous attack of October 7th against Israeli civilians, there was a very important conception that was broken in Israeli society: the conception that we can live with the siege and with the occupation and not feel it. Now, when that conception is broken, we have a vacuum. And there are two ideas that are trying to pull people: one idea that the right is offering, which is, “We can’t live with occupation. We can’t live with siege. This means we need to wipe all of them out,” and the other idea, the moderate one, the one that makes sense, is that “We can’t live with occupation. We can’t live with siege. We need to step forward for peace.”

Inside military prison, I got asked a lot, “What do you think? We should just stop the war and put our hands up and not do anything?” And I would answer, “No, we need to keep fighting. We need to keep fighting for a just future. We need to stop the physical fighting between us, and we need to very, very aggressively push for a better future.”

AMY GOODMAN: I’m wondering your response to Prime Minister Netanyahu once again saying “from the river to the sea.” When Palestinian advocates and their allies talk about “from the river to the sea,” the response of the Israeli government has been, “That means they’re for the genocide of Jews, because they don’t want Jews to be there,” the government says. Now you have Netanyahu saying — not that this hasn’t been said before by Likud — but, “From the river to the sea, Israel must control.” Your response to that, Tal? And if you can talk about the word “occupation”? Because in the U.S. media also, there is rarely that word used, that Israel occupies the West Bank and Gaza.

TAL MITNICK: The term “from the river to the sea” is very controversial inside of Israel. And I feel like some people that use it, there are people that use it that mean the genocide of Jews inside Israel. But just the term itself, I feel like, does not mean a genocide of Jews; it means freedom of all Palestinians from the river to the sea. When Benjamin Netanyahu uses this term, it does not mean freedom for all from the river to the sea; it means oppression of Palestinians, and it means Jewish supremacy from the Jordan River to the Mediterranean Sea.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, Tal, I’m wondering your response to Jews around the world, particularly here in the United States, like Jewish Voice for Peace, these massive protests that have been held, from Grand Central Station to shutting down the bridges and the tunnels from New York, to highways in California, saying, “We want a ceasefire now.” How do you respond to that? And your final message to other 18-year-old Israelis?

TAL MITNICK: These protests are amazing. These organizations, like Jewish Voices for Peace and IfNotNow, do incredible work. And I support the continuation of these protests all around the world.

And a message to other people my age, other kids, I feel like it’s important to know that we have a voice. I used to think that talking to people is all we could do, but we can change, and people want to hear what we have to say because we’re the future. And this is — yeah, we’re the future, and we can change.

AMY GOODMAN: And finally, might you spend months, more than a year in jail if you keep saying no to military service, since Netanyahu says this will go on for more than a year?

TAL MITNICK: Because there’s no policy set for jailing conscientious objectors, I don’t really know how much time I’ll spend in prison, but it could be months.

AMY GOODMAN: Tal Mitnick, 18-year-old Israeli activist, known as a refusenik. He’s refused mandatory military service in the Israeli army, the first conscientious objector in Israel since the Israeli assault on Gaza began over a hundred days ago. He’s just sentenced to 30 days in prison, which he served, for refusing to enlist, was released a few days ago, then will be called up again and says he will refuse again.

***

Horrific Traumatic Injuries of Children: British Dr. Witnesses Israel’s Destruction of Gaza Hospitals

by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

January 19, 2024

https://www.democracynow.org/2024/1/19/ ... transcript

Before Israel’s unprecedented assault on Gaza, the territory had 36 functioning hospitals. Now only 16 partially functioning health facilities remain. As Israeli bombs and ground troops approach Nasser Hospital, the largest remaining partially functioning health facility in Gaza, we speak with Dr. James Smith, an emergency medical doctor recently returned from Gaza, where he worked alongside Palestinian healthcare workers to treat patients at Al-Aqsa Hospital. “Every single day, without exception, there were multiple mass casualty incidents at the hospital,” says Smith. “They would include open chest wounds, open abdominal wounds, traumatic amputations, severe full-thickness burns … really some of the most horrific traumatic injuries that I have ever seen.”

Transcript

This is a rush transcript. Copy may not be in its final form.

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

Israeli forces are pushing further into southern Gaza, with airstrikes and ground troops attacking areas that Israel had previously told Palestinians to flee to as safe zones. Over the past few days, Israel has bombed areas close to Nasser Hospital, the largest remaining semi-functioning health facility in Gaza, located in the southern city of Khan Younis. Gaza only has 16 partially functioning health facilities remaining. Before Israel’s assault, Gaza had 36 hospitals. The hospitals that are still working are operating far beyond their capacity, have been turned into makeshift refugee camps to house the displaced — and makeshift morgues — with health officials describing the situation as catastrophic. The Health Ministry estimates that over 60,000 people have been wounded in Gaza, with hundreds more casualties every day. The casualty count at this point is nearing 25,000, more than 10,000 of them children.

For more, we’re joined by Dr. James Smith, an emergency medical doctor who just returned from Gaza earlier this month, where he worked alongside Palestinian healthcare workers to treat patients at Al-Aqsa Hospital located in Deir al-Balah in the middle of the Gaza Strip. Dr. James was in Gaza with the organization Medical Aid for Palestinians. He’s joining us now from London.

Dr. James, welcome to Democracy Now! Describe what you saw, what you confronted, the work you were doing, what’s happening at Al-Aqsa Hospital.

DR. JAMES SMITH: Hi, Amy.

So, yes, as you say, I was working with a team. There were 10 of us. Myself, I was with the organization Medical Aid for Palestinians. We were accompanied by colleagues from the International Rescue Committee. And very importantly, we were — it’s important to really reiterate that we were working with our Palestinian colleagues, so doctors, nurses, other healthcare professionals, at Al — sorry, at Al-Aqsa Hospital. Al-Aqsa is a hospital based in the middle area of Gaza, so south of Gaza City and north of Khan Younis.

Myself, I was working in the emergency room. So, we would position ourselves in the ER every morning and, really, at that point, wait to see what the day would bring. Every single day, without exception, there were multiple mass casualty incidents at the hospital. So that’s several patients presenting at a time with traumatic injuries of varying severity. Those patients would require stabilization and then often transfer through to the operating room for surgical intervention. Some patients would require palliative care, if we were able to provide some form of palliative care, and in addition to many, many trauma patients. And by “many,” I mean several hundred over the time that we were working at Al-Aqsa. We were also treating patients presenting with complex medical problems, so people that had suffered heart attacks, for example, had suffered from strokes, and people whose hypertension or diabetes management had been negatively impacted, usually through a lack of access to their usual medication or because they hadn’t been able to see their usual doctor for several months. And then, furthermore, we were also seeing an even greater number of people with, effectively, primary healthcare-level problems.

So, the entirety of the primary healthcare or community care system in Gaza has completely collapsed. In fact, the entire healthcare system, the Ministry of Health has already announced several months ago, has completely collapsed. But that meant that anyone presenting with so-called, well, more minor complaints — coughs, colds, diarrheal illnesses — they were all also presenting to the emergency room to be seen by the doctors and nurses there.

AMY GOODMAN: Can you talk about treating children, Dr. James?

DR. JAMES SMITH: Sure. So, as you’ve mentioned, a significant proportion of the people that have been killed since the start of this escalation are children. We certainly saw every mass casualty incident in the emergency room. There were several children also present. I remember very vividly some of the most traumatic injuries inflicted upon people were inflicted upon children. And they would include open chest wounds, open abdominal wounds, traumatic amputations, severe full-thickness burns to a substantial proportion of the body area — really some of the most horrific traumatic injuries that I have ever seen.

AMY GOODMAN: We’re actually showing images for our TV audience of Al-Aqsa Hospital and of the children and the adults who have been wounded there. You know, it’s really important to point out, if you’re talking about a hospital in normal times that has repeatedly been attacked, it would — and that’s severely compromised in its functioning, but we’re talking about this constant bombardment, where you have people coming in who have been severely wounded. You have people taking refuge there. And is it both like a refugee camp and a morgue?

DR. JAMES SMITH: So, there were several thousand people that had sought supposed sanctuary within the hospital compound itself. And we’ve seen this in several other hospitals across the Gaza Strip. There were reports, for example, of thousands of people sheltering in the Al-Shifa compound before that was surrounded and raided by the Israeli occupation forces. The same was the case at Al-Aqsa. So there were people staying in makeshift tents in and around the hospital buildings. Just up the main street adjacent to the hospital, sort of another IDP camp, internally displaced persons camp, had sort of formed very organically on open land. As the Israeli ground forces moved closer to the hospital and as the bombardment, the artillery and air bombardment, intensified, many of those — many thousands of those displaced people have displaced further south towards Rafah. And that also includes patients who were in the hospital at the time that we were working there. Many of them have also fled, along with many of the staff, as well.

AMY GOODMAN: I wanted to go to a clip, and it’s really important to play these clips. Right now Gaza has experienced the longest communications blackout of this Israeli attack for the last three months. I think it’s something like seven days. So it’s really hard to get information inside this intense Israeli bombardment in the vicinity of Nasser Hospital, the main hospital in Khan Younis, the largest remaining semi-functioning health facility in Gaza, and tanks and armored vehicles are on the main road leading to the area. On Wednesday, Democracy Now! reached Dr. Ahmed Moghrabi, who works in Nasser Hospital. He described the situation on the ground and the difficulty in getting out any messages. This is what he had to say.

DR. AHMED MOGHRABI: Thank you, sister, for asking about us. Thank you for letting me speak out here. We don’t have internet at all. I managed to get a very weak signal. I can’t upload any of these videos. Here, 90% of people who are already evacuated at the hospital, they evacuated from the hospital. Ninety percent of medical personnel evacuated from the hospital.

And this is my little daughter, actually. She got head trauma Saturday. You know, hundreds of these evacuating people at the corridor, somebody pushed her, and she fell on her head. Now I’m taking care about my — this little girl. She needs medicine. She’s not well. So I stay at the hospital now, but I want to evacuate. The situation is catastrophic, sister. Really, I’m very tired. I’m very tired.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Dr. Ahmed Moghrabi, and the image we’ve been showing as he spoke was Dr. Moghrabi holding his own wounded daughter. I’m wondering, Dr. James, if you can talk about the significance, the medical significance, of a complete — almost complete telecommunications blackout, in terms of ambulances being reached, people being able to communicate to get help.

DR. JAMES SMITH: Absolutely. I mean, this is a catastrophic development. As you’ve mentioned, Amy, this, I think, is the seventh time that the Israelis have suspended access to telecommunications across almost the entirety of the Gaza Strip. This is now day six or seven of a complete sort of telecommunications blackout. It makes it almost impossible to do anything.

So, in the first instance, people can’t reach their families, their loved ones. They can’t communicate with colleagues. They can’t reassure family that they’re OK, or indeed relatives and friends can’t inform family members and so on when somebody has been killed or injured. There have been occasions where the emergency number has not been in use. So, as you say, it’s been difficult to call ambulances or mobilize ambulances to places where there has been an air or artillery strike. It makes it very difficult for health and humanitarian workers to do their essential work —

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. Smith, we —

DR. JAMES SMITH: — so they can’t coordinate with each other.

AMY GOODMAN: We only have 10 seconds. What message do you have for the world, just having come out of Gaza? Ten seconds.

DR. JAMES SMITH: The violence needs to end immediately.

AMY GOODMAN: Dr. James Smith, emergency medical doctor, just back from Gaza, where he worked to treat patients at Al-Aqsa Hospital.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 40234

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: U.S. Backing Has Given Israel License to Kill & Maim

Palestinian Poet Mosab Abu Toha Decries Israel’s “Inhumane” Assault as Gaza Death Toll Tops 25,000

by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

JANUARY 22, 2024

https://www.democracynow.org/2024/1/22/ ... transcript

Transcript