by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

JANUARY 25, 2024

https://www.democracynow.org/2024/1/25/ ... transcript

Transcript

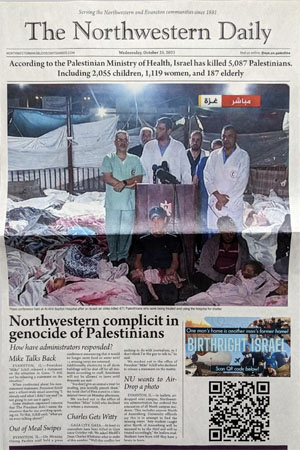

We go to Rafah to speak with Palestinian journalist Akram al-Satarri in Gaza as the death toll continues to climb amid Israel’s relentless assault on the territory. The Health Ministry says at least 20 people were killed Thursday as they lined up to receive humanitarian aid, and at least 12 others were killed a day earlier at a U.N. shelter hit by tank shells. Meanwhile, Israeli forces have surrounded the two main hospitals in Khan Younis, stranding thousands of patients and displaced people inside, and evacuated a third hospital. Over 1.7 million people have been displaced in Gaza and more than 25,000 have been killed in Israel’s assault over the past three months, as the population continues to move further south in a desperate search for safety. “People are dying. People are scared,” says al-Satarri. “There is an eradication attempt that is taking place in Gaza.”

AMY GOODMAN: We begin today’s show in Gaza, where the death toll continues to climb and Israel’s relentless assault continues. At least 20 Palestinians were killed today and 150 injured as they were lining up for humanitarian aid in Gaza City, this according to the Palestinian Health Ministry, with the number of casualties expected to rise.

The attack comes one day after a crowded U.N. shelter housing tens of thousands of displaced Palestinians in Khan Younis was struck on Wednesday, setting the building on fire. At least 12 people were killed, over 75 wounded, when two tank shells hit the site, according to the U.N. agency for Palestinian refugees, known as UNRWA. The Israeli military, the only actor on the ground that has tanks, denied it carried out the strike.

Meanwhile, the Israeli army has surrounded and isolated the two main hospitals in Khan Younis, Nasser and al-Amal, stranding hundreds of patients and thousands of displaced people inside, that again according to UNRWA. A third hospital was evacuated overnight.

In recent days, thousands more Palestinians have rushed to escape further south, crowding into shelters and tent camps near the border with Egypt. Over 1.7 million people have been displaced in Gaza, and more than 25,000 have been killed in Israel’s assault over the past three months.

We go now to Rafah, where we’re joined by Akram al-Satarri, a journalist who’s been covering developments on the ground. He’s joining us from just outside the Yousef al-Najjar Hospital in Rafah, the southernmost city in Gaza.

Akram, welcome back to Democracy Now! Can you describe what’s happening in Rafah and the reports of what’s happening in Khan Younis?

AKRAM AL-SATARRI: Well, the situation in Khan Younis is aggravating in such a very serious way. The bombardment and the targeting around the hospitals that you have just mentioned — al-Amal Hospital in Khan Younis, in the Khan Younis al-Amal neighborhood; Al-Khair Hospital, that was stormed by the Israeli occupation forces, and people there who are staff were interrogated, and people who are internally displaced people were arrested. Nasser Hospital has been the subject to some massive attacks, and some of those attacks targeted also UNRWA-designated shelters that are located in the immediate vicinity of the Nasser Hospital. The clinic, the UNRWA clinic that is in the heart of Khan Younis refugee camp, was — the area of its vicinity was also targeted.

People were asked to leave their homes. And some of the people who were leaving their homes were reporting about a journey of horror, devastation and imminent death that they have been seeing. They have been reporting about them seeing the people who are dead on the ground, without anyone daring to reach them or to collect their bodies or to try to extend a helping hand for the people who are screaming for help because of their lethal and bloody injuries.

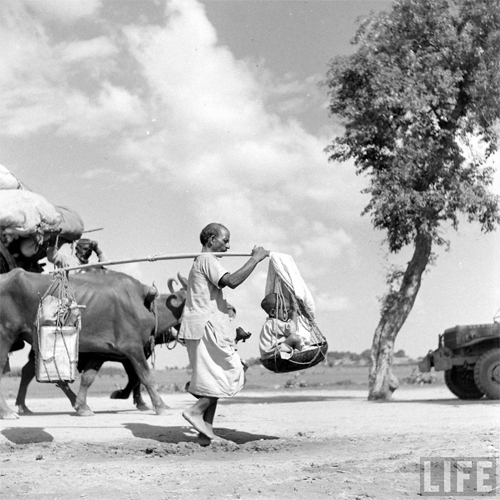

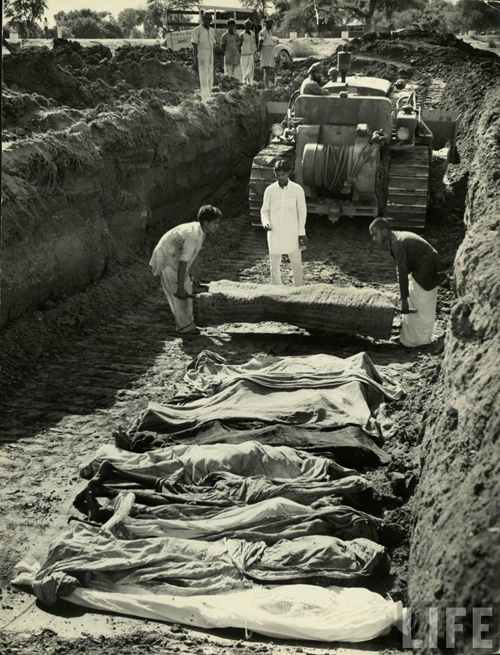

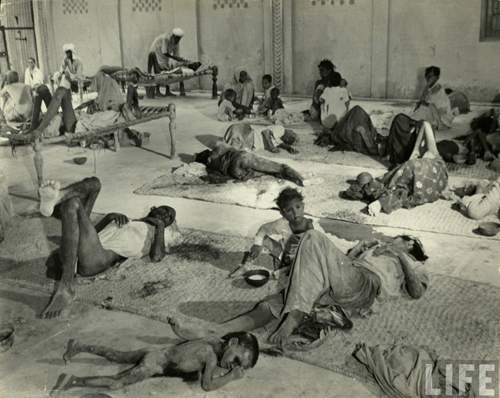

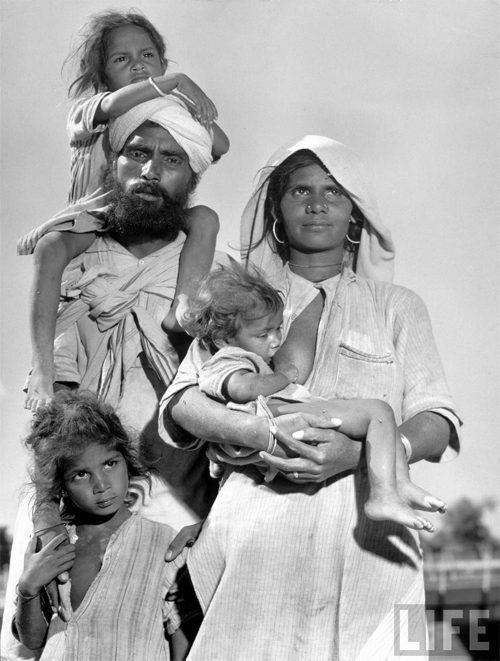

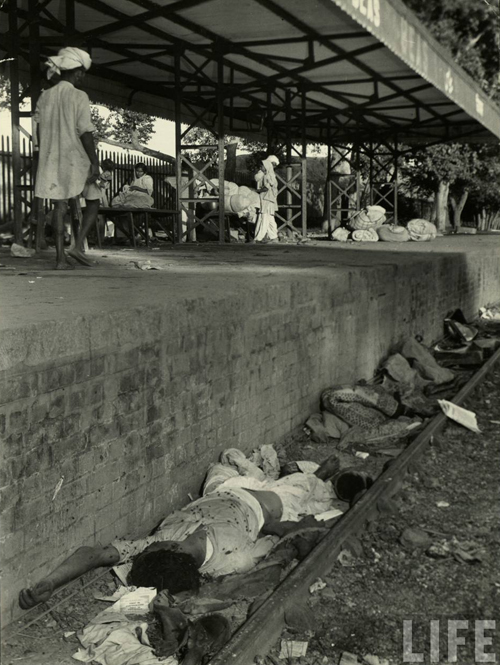

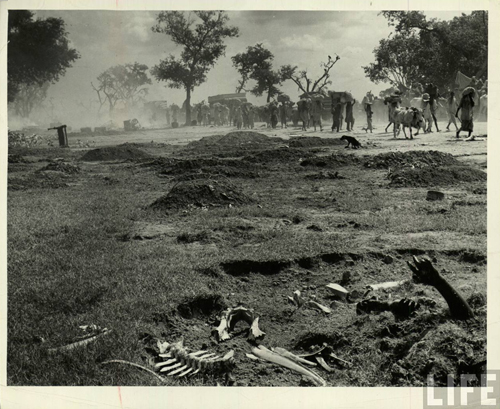

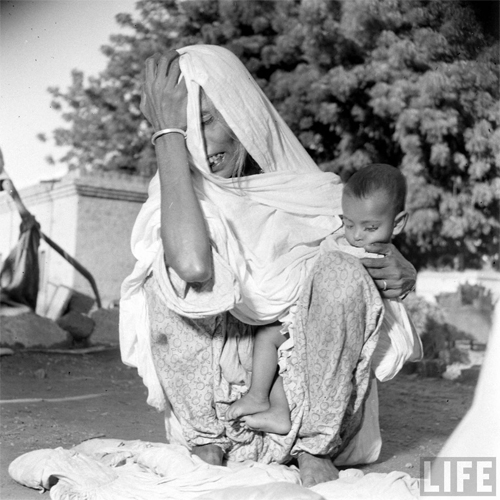

AND THESE PEOPLE AREN'T EVEN BEING BOMBED AND GASSED!

-- Mass Migration During Independence of India and Pakistan in 1947, by Margaret Bourke-White, Life Magazine, 1947

Palestinians carry their belongings as they leave their homes and flee from Khan Younis, Gaza on Tuesday. cnn.com

Boy sits amid rubble of destroyed homes in Gaza. bbc.com

Palestinians fleeing north Gaza move southward, in the central Gaza Strip. reuters.com

Families leave north Gaza after warnings from Israeli military. bbc.com

A Palestinian on a wheelchair passes by ruins of buildings destroyed in Israeli strikes, in Rafah in the southern Gaza Strip October 9, 2023. REUTERS/Ibraheem Abu Mustafa

Palestinians carry bags of flour they grabbed from an aid truck near an Israeli checkpoint, as Gaza residents face crisis levels of hunger, amid the ongoing conflict between Israel and Hamas, in Gaza City January 27, 2024. REUTERS/Hossam Azam

The U.N. has set up tents at a refugee camp for Palestinians in Khan Yunis, in the Gaza Strip near the Egyptian border. (Photo by Mahmud Hams/AFP via Getty Images)

The KYTC, that is run by the UNRWA, and that is also recognized by Israel as a designated shelter and protected shelter, was targeted once again. And now people who are staying in there, who are in thousands, are asked by the Israeli occupation to move from that area towards Rafah area in the very south, which means that there is more targeting underway, which means that they would be afraid and the ones who were killed and injured who were taken to Rafah rather than to Khan Younis because of the fact that the Israeli occupation closed the way between Khan Younis coastal area and Khan Younis refugee camp and Khan Younis downtown. So the situation is aggravating in that way. Hundreds of people are injured. Tens of people are killed.

Also, not far away from Khan Younis, in Gaza City, the people who were waiting in al-Kuwait roundabout were targeted. They were waiting for the humanitarian assistance because the situation in Gaza City and the north is extremely dire. People are already suffering from famine, very lacking situation when it comes to the food supplies and drinkable water. They’re waiting there. Twenty — as you said, 20 were killed, 150 others were injured. The new about this report is that among those 150, there is a very large number of people who are sustaining very critical, life-threatening injuries and who might be reported as killed, which means the number of victims of this bloody attack is expected to rise significantly in the coming hours.

So, the situation continues to feature large-scale bombardment in Khan Younis, displacement of people, destroying of whole blocks and houses, people moving, and they end up targeted when they are moving. Designated shelters that are supposed to be protected, now the people in them are asked to be IDPs once again, given that the IDPs in that area are coming mainly from the north, people who moved from the north to Gaza City, then moved from Gaza City to Gaza central area, then moved from Gaza central area to Khan Younis area. And then, from Khan Younis, they moved to the KYTC, and they are now asked for the fifth or sixth time to leave the area that they were seeking safety in, and to move in a very unsafe path towards the unknown in southern Gaza, in Rafah, which the targeting is still continuous. Number of people who are killed in Rafah is still increasing. And the Gazans, at large, are not aware what the future holds of them, with the number of IDPs reaching 1.9 million Gazans in all different areas, including the coastal area in Khan Younis and the already heavy-populated area in Rafah.

AMY GOODMAN: ”IDP” is, of course, internally displaced people. Akram, if you can describe the telecommunications blackout and the effect it has on people trying to communicate with each other, find each other, get to hospitals, reporting of injuries? And also, I don’t take for granted that we’re able even to speak to you today in Rafah, in Gaza. And if you can talk about how you both report and take care of your own family?

AKRAM AL-SATARRI: Well, if I may speak from a very personal perspective, I personally was under that imminent threat of death in Khan Younis. I lost communication with my family, with my sister, with my nephews and nieces who lost their father. I lost contact with my son. I was wondering how can I possibly survive under the imminent threat of fire.

And when I say an imminent threat of fire and death, I mean that seven people were targeted at the door of our home, the home that was hosting us. And the seven people, no one ambulance could reach them. We were trying to call 111, which is the ambulance services — sorry, 101, which is the ambulance services. We could not get through to them.

The communication blackout looks — it looks like it was intentional for the sake of cutting all communication and cutting the coverage and trying to keep Gaza isolated from the world and keep Gaza voiceless at the time that the Israeli occupation was developing the ground operation and was targeting the different areas in Khan Younis and throughout the Gaza Strip. I lost communication, and I was — and am still — facing significant challenges reporting, moving. And you never know. When you are just driving a car or just driving a taxi, or just even riding an animal-pulled cart, you don’t know whether they are going to target someone who’s walking down the street, someone who’s next to you on that animal-pulled cart, or maybe they would target you. So, it’s very difficult to understand in Gaza what’s coming next. It’s very difficult to predict who they are going to target. It’s very difficult to predict why they are targeting people.

But the bottom line, and the conclusion that we see with our own eyes, that the targeting is thorough, the destruction is larger than ever, and the suffering of the people because of that ongoing policy is unconceivable, unconceivable in the sense that I personally had to move and see the people who are dead and to try to move, and while five or six other houses around me were targeted, while I could see the artillery fire taking out whole house when I was moving in the Khan Younis area and was staying in the area that I was waiting for the situation to be a little bit safer to move, but it turned out the situation was getting from bad to worse, and the targeting was getting heavier. I was staying in the area that is called 111 area, which is a block that was designated by Israel as a safe area. And across from our area was 112 block. But the bombardment was in 111, 112, 107, 48, 86. All the blocks were targeted all at once. And that ground operation seemed to be indiscriminately sending death and destruction all over the area.

So, with that comes, as you have just said, the struggle to survive, to struggle to stay sane under this ever-escalating situation and to look for one minute of peace. I was personally thinking just yesterday that we are wanting some one second of rest and peace, even if that means we would die, even if that means they would take us, even if that means they take our life for the sake of just keeping us peaceful.

So, this is how it unfolded in Gaza, and this is how it continues to unfold. People are dying. People are scared. People are displaced. And they think they are even uprooted intentionally and there is an eradication attempt that is taking place in Gaza. The Israeli occupation has been targeting every single corner in Khan Younis. Khan Younis refugee camp, that is extremely populated and overcrowded, was targeted. When you target one house in one specific area, that means you are likely to affect around 20 to 30 houses, because the areas are very narrow, and the space, that is limited for every house. And targeting one place, explosion in one place means that this explosion, the implication of that explosion, would reach — or, the secondary wave of the explosion would reach around 20 to 30 houses.

AMY GOODMAN: Did you know the reporters that were killed most recently? I mean, the numbers are just astonishing. The Committee to Protect Journalists, Reporters Without Borders are all decrying the number, ranging between 80 and 120. But the latest killing of journalists, for example, Wael al-Dahdouh’s son, Hamza al-Dahdouh — did you know Mustafa Thuraya? Did you — I know that Wael has just gotten out of Gaza. He’s head of the —

AKRAM AL-SATARRI: I think we lost the connection.

AMY GOODMAN: — Al Jazeera — and he has now been operated on in Qatar. He’s now at Al Jazeera headquarters. His cameraman, Samer Abudaqa, who died in the attack. These reporters, were they friends of yours?

I think we have just lost Akram. Absolutely amazing that we were able to maintain that length of time in speaking to him in Gaza. He was speaking to us from Rafah. Akram al-Satarri is a Gaza-based journalist, joining us from southern Gaza.

This is Democracy Now! When we come back, Palestinian tax revenue, Israel is refusing to release it but has made an agreement with Norway to hold it in escrow. What’s happening to Palestinians’ money? We’ll speak with a leading economist in Ramallah. Stay with us.

***

Palestinian Economist Raja Khalidi on Israel’s “Economic Warfare” on Gaza and the West Bank

by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

JANUARY 25, 2024

https://www.democracynow.org/2024/1/25/ ... transcript

Transcript

Among the consequences of Israel’s war on Gaza is the destruction of the local economy. Even before the latest Israeli assault, daily life and commerce in Gaza were crumbling as a result of a 15-year siege on the territory enforced by Israel and Egypt. Meanwhile, Israel is withholding millions in taxes collected on behalf of Palestinians, leaving the Palestinian Authority unable to distribute wages to many public sector employees, while more than 150,000 Palestinian workers from the West Bank are now unable to work inside Israel due to new restrictions imposed after October 7. We go to Ramallah to speak with economist Raja Khalidi, director general of the Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute. Khalidi says Israel is using a range of tools in its “economic warfare” against Palestinians, and warns, “We are on the precipice of a warlike situation in the West Bank.”

AMY GOODMAN: This is Democracy Now!, democracynow.org, The War and Peace Report. I’m Amy Goodman.

Israel’s assault on Gaza has exacted a devastating toll, with over 25,000 people killed, 63,000 wounded, 1.7 million, at least, displaced. And among the consequences of the offensive is the decimation of Gaza’s economy. Even before the latest Israeli assault on Gaza began over three months ago, Gaza’s economy was already crumbling, the result of a 15-year-long siege on the territory enforced by Israel and Egypt. Now with vast swaths of Gaza destroyed by the Israeli military and severe restrictions on humanitarian aid coming in, more than half a million people are facing catastrophic hunger. That’s according to the United Nations.

Meanwhile, Israel is withholding millions in taxes collected on behalf of Palestinians earmarked for Gaza. On Sunday, Israel approved a plan to send those tax revenues it’s frozen since November to Norway to be held in escrow, instead of the Palestinian Authority. While the PA was ousted from Gaza in 2007, many of its public sector workers kept their jobs and continue to be paid with transferred tax revenues that are being held by Israel, further exacerbating the crisis in Gaza.

For more, we’re joined by Raja Khalidi. He’s the director general of the Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute, joining us from Ramallah in the occupied West Bank.

Raja, thanks so much for being with us. If you can start off by talking about whose money is this? And talk about the amount that’s supposed to go to Gaza and to the West Bank, and how Israel has control over it. Why do they have control over it?

RAJA KHALIDI: Thanks a lot, Amy, and for this chance to talk with you.

Before plunging into the dirty details of the economics of this war, I just want to just say a word of tribute to the journalists, like Akram, so many of them who have been reporting, who have been shocking us every day. And what is more shocking — and we’re talking about millions of us watching, listening around the world, here and the rest of Palestine. What is most shocking is that they’re able to still do their job so well and so professionally. So, I mean, we’ll come back to Gaza, but, really, you know, you don’t need an economist to tell you to what’s happened to the economy of Gaza. We just heard a lot. It tells so much of a story.

The entanglement of Palestinian Authority’s public finances with Israel goes back to Oslo. Funnily enough, it’s come back home to Oslo, in the sense that this was all part of an arrangement made for a five-year period whereby Israel was allowed, because of — de facto, when Oslo agreements were signed, to control the collection of Palestinian external trade taxes at its borders, because it, of course, controls all the Palestinian trade, both that trade that comes from the Israeli economy, as well as from around the world. So, that set up a mechanism called the clearance mechanism, whereby all of the recorded imports, through Israel or from Israel to the PA, are calculated and handed over on a monthly basis to the Palestinian Authority. Now, this was a suitable arrangement in the interim period that was supposed to end in 2000, but then it was perpetuated because nothing else took its place since then, but gradually interpreted unilaterally by Israel in its own — according to its own financial security and political interests.

So, from early on, this mechanism became one of the weapons, if you wish, of economic warfare, and pacification or warfare, so carrot or stick, that Israel has used in its relationship with the Palestinian economy, with Palestine, with the Palestinian people. Now, that has entailed, over the years, especially in the last five or six years, unilateral deductions that Israel makes. So, it makes deductions for electricity consumption that it claims has not been paid, for water, sewage, etc., treatment, and for other, medical referrals to Israeli hospitals, and then — which is something the PA came to accept, because it had no fiscal leverage against Israel. And then, in the last five years, Israel, of course, has been deducting sums equivalent to what the PA pays to the prisoners’ and martyrs’ families — again, at loud protest by the PA, but with little effect. This is an issue that the, you know, Norwegians, the AHLC, the IMF have been seized with for years, but nobody has done anything about. So, you know, this most recent unilateral decision by an extremist settler government to deduct what they claim is the equivalent of what the PA continues to pay salaries to its former, I mean, employees, but who are now actually not mainly working in the West Bank [inaudible], you know, is something that — what can we expect the PA to do? I mean, it tried to reject it out of principle, but, on the other hand, it’s collapsing. Its fiscal situation is near disastrous.

So, exactly what this entails, this escrow account, I mean, if it means that the PA can say, “Well, at least Israel is not holding the money that it illegally deducted, and we reject totally its deduction, hence we’ll take the rest,” OK, that’s going to allow it to stumble through the next couple months perhaps, make some new, you know, refinancing — debt refinancing deals, etc., with the banking system, and eventually hope that when things calm down, Smotrich will allow the Norwegians to release the funds, which, again, is perhaps somewhat fantastical. Perhaps it’s better to say it’s better to have the Norwegians holding it than — but that’s it. I mean, it doesn’t really change the equation, except that it deblocks a certain amount of Palestinian trade revenue. On the other hand, we’ve got to realize that this trade revenue is directly linked to the level of economic activity, and the level of economic activity in the West Bank has collapsed — I mean, not as much, of course, as Gaza, which is now a — is a non-economy, in fact. But in the West Bank it’s been more about the return of workers from Israel and what they are no longer spending in the local economy for four months, the cutoff of clearance revenues. But most importantly is the general reduction in economic activity means that we’re importing less. So, if we’re importing less, there’s less revenue. So, the average monthly revenue is going down regardless of Israeli deductions.

AMY GOODMAN: So, talk about the effects on the ground of not having this money. And who exactly in the current government is deciding who gets what? I mean, you talk about Smotrich. There’s Ben-Gvir. Of course, there’s Netanyahu. What’s happening with — what’s happening in the West Bank? What’s happening in Gaza? And where does the U.S. stand on this? And that’s a critical question, because the U.S. actually can exert so much control, given, as one Israeli general said, that almost all of their weapons are from the United States, that they could not move ahead with what they’re doing with Gaza without U.S. support.

RAJA KHALIDI: It’s arguable as to how much control the United States actually has on this government, to begin with. But regardless of that, we know that it doesn’t want — the United States does not want to exercise any serious influence on this file, for example. All it was able to do is to come up with this Norway escrow account deal, which doesn’t really do anything, because it’s not going to be compensated to — it says that money can neither be transferred to the PA nor used as a loan to the PA. Now, maybe it’s going to mean that the PA can borrow — which it should be able to do, because it’s supposedly a government — on, you know, internationally, to fund part of its deficit. But that’s, again, another stopgap measure. So, the PA, there’s very few decision-makers on this in the Palestinian Authority. There’s the president and the prime minister and the minister of finance. And they’re going and coming, I presume, with the different interlocutors, trying to come up with something that keeps the treasury able to pay part of its salaries bill.

The salary bill in the West Bank is about $4 billion a year, which is about 80% of the public budget. So, you know, that has already been cut prior to the war, because of other reasons, because of the deductions that we mentioned. So, salaried employees are receiving less, paying less, less able to repay their debts, which they’ve taken out in, you know, extreme ways, or private consumption debts over the last five, six years, in the good times, so to speak. And then you have — so, you have all of that reduction in aggregate demand from — purchasing power and aggregate demand.

And then you have the workers who have returned from Israel, 180,000 people, maybe 150,000 of whom were sitting in their villages and camps waiting for something to happen, and nothing is happening. I mean, you know, there’s very few alternative jobs in the local market, to begin with. They had become lazy, if you wish, or the labor force had become, you know, dependent, let’s say, on this option of working in Israel, which brings in two to three times local wages.

So there’s a major transformation undergoing in the local economy. We’re going to see extreme poverty increasing in the West Bank, which it was less severe incidents in the past than Gaza, for example. We’re going to see growing social deprivation and inability of the PA, because it doesn’t have any money, hardly, to pay its salaries, much less to provide services to the poor. I mean, education system is continuing, but it’s starting to be hobbled, and so on and so forth. So there’s a gradual — I don’t want to call it a collapse of the Palestinian Authority’s ability to deliver its services, but certainly a retraction and entrenchment.

AMY GOODMAN: Let me ask you about the labor situation, because so many thousands of Palestinians worked in Israel proper. Israel is looking to address the major labor shortage because they’re not allowing Palestinians from the Occupied Territories to work in Israel, but by recruiting tens of thousands of people from India, at a time when Palestinians have long played a crucial role in Israeli construction and other sectors, who are now barred. Israeli authorities say they’re hoping to see 10,000 to 20,000 Indian migrant workers in the coming months, a deal that’s being worked out with Narendra Modi, the prime minister of India. What about this?

RAJA KHALIDI: Well, look, I mean, 10,000 to 20,000 is not going to really do anything except perhaps get the next agricultural season crop in and build a few buildings that have been waiting to be completed. Palestinians, there were approximately 90,000, 85,000 Palestinians, of the total 180,000 — more than half of them were working in — 80,000 — more than half of them were working in Israel, Israeli construction. So, I mean, our labor force is highly dependent on the Israeli Construction Center, and the Israeli Construction Center is highly dependent on our labor. So, replacing a part of that, yeah, a stopgap measure.

In agriculture, I believe they’re trying to do something similar with workers from Africa. But, you know, there’s a reason that unlike, let’s say, Gulf states, many Arab Gulf states — the Asian labor force en masse has built the Gulf countries, if you wish. Israel does not want to find itself in that situation. And that’s because, you know, the exploitation of Palestinian labor is easy. They’re next door. They go home at night. And, you know, they’re not going to make trouble. On the other hand, the idea of — you know, and Israel is a — culturally, is not very open and tolerant to pick people of color, even, you know, Jews and Palestinians of color. So, I think that these Asian and, wherever they might come from, African workers are going to face a lot of issues in the discrimination, in what is really an apartheid, if you wish, labor market. Palestinians from the West Bank had a certain position prior to the war. Twenty thousand Gazawis were allowed in and were working. So, there’s this sort of hierarchy. And then you have Arabs in Israel who are slightly higher up the occupation ladder, but — etc., etc. So, where are these Asian workers, who are not going to go home at night, where they’re going to — you know, how they’re going to use them, integrate them, except in a short-term wartime economy, I don’t think it’s a viable option.

But the other option of Israel, you know, you mentioned Smotrich. He’s one of those who are, you know, dead against such a return of Palestinian labor into Israeli markets. So, you know, they can’t have their cake and eat it, too. And I would hope that, you know, a certain amount — I think, for sure, a certain number will be allowed in gradually. But I fear it will be in chain gang-like circumstances, you know, with high security around them, only a few hours, etc., etc. And there will be a lot of room for exploitation by bosses and contractors and people who issue permits and things like that. So, you know, I think that’s the way that one is going to play out.

AMY GOODMAN: Finally, we just have a minute, but, Raja Khalidi, you’re sitting there in Ramallah. The occupied West Bank, the Israeli military has raided Ramallah, Bethlehem, Jenin repeatedly, as well as many other areas. If you could just describe what it’s like living there on the ground, not to mention what’s happening in Gaza, and if you see any kind of end of this violence in sight?

RAJA KHALIDI: It’s frightening. I mean, I haven’t left Ramallah for the last four months except three times. And many people are living, sheltering in place. Three hundred fifty thousand Palestinians in Jerusalem have not left Jerusalem for the last four months, whereas they’re usually coming and going to Ramallah and around West Bank all the time. So there is a sense of fear, of lack of mobilization, except at the very local level.

There is no national authority that is engaging and confronting either the settler attacks or the expansion of settlements. We’re seeing settlements, outposts and roads popping up every day on the roads between the major Palestinian cities. Roadblocks have increased, from 550 before the war to 700, and so on and so forth. I had never lived in Palestine under such circumstances. For me, I perhaps have greater access, etc., but it’s not easy for anybody. And for people trying to get to work, people trying to get to hospitals, people — I mean, it’s — and then there is the violence. You never know when — you know, if you go down the wrong road, some settler gang will stone your car, burn it, whatever. That’s not to mention the Israeli army’s campaign against — you mentioned, very correctly, several cities have been devastated, tens of millions of dollars of infrastructure, basically mini Gazas in Jenin, Nablus and Tulkarem. And I think that’s intentional. It’s sending a message. And it’s telling us what’s in store for us if anybody raises their head.

And, you know, to be honest, Gaza is a total catastrophe, but it could get worse if they continue in the West Bank. So, if we get to a ceasefire, I hope it’s a comprehensive one, and it’s not only hostilities in Gaza, because we’re at the precipice of a warlike situation in the West Bank. And we don’t have any resistance fighters, in the sense that Gaza has, let’s say, you know, so it’s really everybody in the West Bank who’s going to be drawn into this if things go bad.

AMY GOODMAN: Raja Khalidi is the director general of the Palestine Economic Policy Research Institute.

Next up, the New York Police Department has launched an investigation after Columbia University students were attacked with a chemical spray during a pro-Palestine demonstration last week. Stay with us.

***

Professors Slam Columbia’s Response to Chemical Skunk Attack on Students at Pro-Palestine Protest

by Amy Goodman

DemocracyNow!

JANUARY 25, 2024

Transcript

Students at Columbia University in New York held an “emergency protest” Wednesday over the school’s response to an attack on members of Columbia University Apartheid Divest at a rally on campus last Friday. Police in New York are investigating the attack on pro-Palestinian students, who say they were sprayed with a foul-smelling chemical. Eight students were reportedly hospitalized, complaining of burning eyes, headaches, nausea and other symptoms. Organizers allege the attack was carried out by two students who are former members of the Israeli military, using a chemical weapon known as “skunk” that the Israeli military and security forces regularly deploy against Palestinians. The university responded to the attack by first scolding the organizers for holding an “unsanctioned” rally, then later said it had banned the suspects from campus while police investigate. This comes after Columbia administrators banned the local chapters of Students for Justice in Palestine and Jewish Voice for Peace in November, with students describing a climate of censorship and retaliation for pro-Palestinian activism on campus. “Overall, it’s been a very clumsy handling,” Columbia professor Mahmood Mamdani says of the school’s response to student protests and campus safety. We also speak with Columbia Law School professor Katherine Franke, who says concerned faculty “have been spending an enormous amount of time protecting our students from the university itself.”

AMY GOODMAN: Students at Columbia University here in New York held an “emergency protest” Wednesday over the school’s response to an attack on members of Columbia University Apartheid Divest at a rally on campus last Friday. Police are now investigating how pro-Palestinian students were sprayed with a hazardous, foul-smelling chemical at Friday’s protest, including members of Students for Justice in Palestine, Jewish Voice for Peace and Jews for Ceasefire. Eight students were reportedly hospitalized or seeking medical attention. Organizers allege the attack was carried out by two students who are former members of the Israeli military, the IDF, using a chemical weapon known as “skunk” that soldiers also deploy on Palestinians.

A Palestinian American student named Layla described the attack she says has left her traumatized, in an interview with the podcast The Robust Opposition.

LAYLA: I remember smelling this smell in the air, and it is just — it was just atrocious. I was like, “Oh my gosh! Like, it smells like somebody died. Like, what is this smell?” And then, at first, I was like, “OK, maybe I stepped in some dog poop. Like, maybe I’m just tired.” I tried to, like, kind of ignore it for a little bit.

But then, after the protest, when the protest was done, I just noticed how bad I felt. I felt so sick. I felt fatigued. I was nauseous. I had a really bad headache. And I was like, “Something is going on here. I’m not sure what, but something is going on here.” And then I was getting texts and calls from my friends. And they were like, “Did you smell that smell?” Or my friend was like, “Oh my gosh! I threw up like three times. Like, I don’t know what is wrong with me.” …

So, when this is used on Palestinians in the West Bank, like, for example, it’s been used on peaceful protesters there. It’s been used on shopkeepers and merchants. So, like, if a merchant gets their produce sprayed with skunk, they have to throw it all out, just because of how bad it stinks. …

It felt like for a while like the university, like, didn’t believe us. Like, I told them about it, and it’s like my concerns weren’t really being taken seriously. And it wasn’t until students started posting photos of themselves being hospitalized, and tagging the university, being, like, at Columbia, like we are — like, they started taking it seriously.

AMY GOODMAN: That’s Palestinian American Columbia University student Layla describing Friday’s attack on her, as well as other students who were part of a protest. No arrests have been made yet, but the school now says it’s banned the suspects from campus while law enforcement investigates.

For more, we’re joined by Mahmood Mamdani, professor of government at Columbia University who specializes in the study of colonialism. His books include Neither Settler Nor Native: The Making and Unmaking of Permanent Minorities. His recent interview with The Nation is headlined “The Idea of the Nation-State Is Synonymous with Genocide.” And we’re joined by Katherine Franke, a Columbia Law School professor, member of the Center for Palestine Studies executive committee, on the board of Palestine Legal, helped write a new op-ed in the campus paper, the Columbia Spectator, headlined “Faculty and staff pledge to take back our University.”

We welcome you both to Democracy Now! Professor Franke, can you explain what happened, the skunking of the students, sprayed with this chemical? Do you know, does the university know, who these students were, where they came from? And have they been dealt with?

KATHERINE FRANKE: Well, good morning, Amy.

So, the students were protesting in the main quad of the university last Friday. And we’ve had a series of protests. Our students are outraged at what’s going on, in our name and with our tax dollars, in Gaza. And while they were protesting — and, I will say, peacefully — last Friday, as your recording of Layla’s recounting of what happened, they all of the sudden smelled this horrible stench. And I’ve smelled skunk water when I’ve been in the West Bank at protests. It is horrible.

And what the students were able to do is examine video from that protest and identify, I think, three older students. We have a — Columbia has a program. It’s a graduate relationship with older students from other countries, including Israel. And it’s something that many of us were concerned about, because so many of those Israeli students, who then come to the Columbia campus, are coming right out of their military service. And they’ve been known to harass Palestinian and other students on our campus. And it’s something the university has not taken seriously in the past. But we’ve never seen anything like this. And the students were able to identify three of these exchange students, basically, from Israel, who had just come out of military service, who were spraying the pro-Palestinian students with this skunk water. And they were disguised in keffiyehs so that they could mix in with the students who were demanding that the university divest from companies that are supporting the occupation and the war, and were protesting and demanding a ceasefire. So we know who they were.

The university waited three or four days to actually even say anything about it. They have not reached out to the students who were sick, as you noted, some of whom are still in the hospital. I spoke to one student last night in the hopes that we could get one of them on your show this morning, and he was so mentally and physically disabled from this attack that he said, “I haven’t left my dorm room in a week.” So, our students are in terrible distress about this, both those who were sprayed and those who weren’t. There was another protest yesterday, and the students were actually quite afraid to come back onto the campus.

AMY GOODMAN: Is it true that you’ve seen these students, the former IDF students, on campus? And what is the administration saying about that since the attack?

KATHERINE FRANKE: Well, the university says that they have banned the three identified students from the campus. But I was told that one of them was there yesterday. Other students saw him. I don’t know that for sure, but several students said they saw one of them. You know, we have a fairly porous campus. To ban them from campus is something that they’d have to volunteer to comply with, except when there is a demonstration, when they lock — they’ve started locking the campus down in the last several months with gates, and you have to have your ID to get scanned to enter the campus. And then there’s a wall of NYPD. When I went to class yesterday, there were hundreds of NYPD officers, in uniform, lining our campus.

So, the university’s response has not been compassion, support for the students who were attacked. Instead, it’s been a militarization of our own campus and a further restraint on our students’ ability to protest peacefully, now turning to the excuse of this attack from those who support the Israeli government and the violence that’s being meted out towards Gazans as a kind of pretext to clamp down even further on peaceful protest by our other students.

AMY GOODMAN: Mahmood Mamdani, you have written about the situation in Gaza. You’ve spoken about it. There are now over 25,000 Palestinians who have been killed, over 11,000 of them children. The issue of hunger in Gaza is a very serious issue, raised by the U.N. and medical groups. You have that situation there and the solidarity expressed with the people in Palestine on college campuses. Can you talk about what’s happening at Columbia, and both staff, professors’, students’ feelings about whether they can express their views without being doxxed or attacked?

MAHMOOD MAMDANI: Thank you, Amy.

The situation at Columbia has been developing. It’s monitored by an administration which seem to have very little idea about what to do. At the same time, it had certain assumptions. The assumption was that the main problem at Columbia is antisemitism, and the administration should do everything to keep it in check and then to eradicate it.

When incidents like this, the chemical spraying, emerged, the administration’s first response was kind of disbelief. “Give us the facts.” Overall, it’s been a very clumsy handling. Different parts of the administration have different and sometimes conflicting initiatives. At the same time, they have a coherence. And the coherence is basically to shut things down and only to have an opening from the top, so no question of freedom of expression from below. That’s where we are now. Meanwhile, the community is convinced that the shots are being called by those who give the money.

AMY GOODMAN: So, how are you organizing, as a professor, with other professors, with students?

MAHMOOD MAMDANI: I think the number of concerned professors is growing. We’re all convinced that the initiative must remain with the students. They are in the frontline. But also we’re convinced that we should offer whatever guidance we can offer. We meet and discuss. I personally have not been involved in face-to-face meetings much because of health issues. But I have been involved in meetings which are remote meetings. And it’s changing every day, and it’s developing.

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Franke, last semester Columbia University, the new president at Columbia, suspended both SJP, Students for Justice in Palestine, as well as Jewish Voice for Peace for holding a so-called unauthorized event, a walkout and art display in support of a ceasefire in Gaza. So, what are these groups’ status right now? And also, you yourself have long been involved with issues around Palestine. In fact, Israel deported you. And explain why. This was before October 7th.

KATHERINE FRANKE: Well, my circumstances are much less acute than the circumstances of our students right now. You know, I’ve been part of the Barnard and Columbia community since the late '70s. I went to Barnard as an undergrad. And I've been at Columbia now as a professor for 25 years. Columbia’s campus has always been a place where students have engaged the most critical issues of the day. When I was there in the late '70s, it was issues around feminism and pornography and sexual rights. And later, there were things around the Iraq War and the invitation of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad to the campus. You know, students, faculty have used the campus as a palette for learning about difficult issues — that's what we do at universities — for protesting or showing up for communities that are persecuted around the world.

And what we’ve seen this administration do since October 8th is kind of go to war against our students. I have never seen the university disband student groups for peaceful protest. We have scores, 30, 40, 50 complaints that the university has filed against students for violations of the disciplinary code or for organizing protests, based on their changing of the rules around how to have an event the night before the event, so that the students don’t even know that they’re violating some new event rule. The university said that SJP and JVP had to be suspended because they engaged in intimidating and threatening and antisemitic rhetoric. And then, in private meetings with them, they said, actually they didn’t, but they won’t retract that. So, that defamation of our students remains in the public and in the media and in the eyes and ears of our alums and of other students, but they won’t repudiate it.

And so, the students feel like they have nothing left that they can do, except protest against the university at this point. But Professor Mamdani and I and other faculty have been spending an enormous amount of time protecting our students from the university itself. Barnard students are being prosecuted for their social media posts and for hanging Palestinian flags outside of their dorm rooms, when New York City law specifically protects the hanging of flags outside of a dormitory. So, it feels like we’re under a kind of siege, too, at Columbia and at Barnard.

AMY GOODMAN: Professor Mamdani, before you were a professor at Columbia, you were a professor and director of the Centre for African Studies at the University of Cape Town in South Africa. Tomorrow, the decision will come out of the International Court of Justice, an emergency decision on South Africa’s case, genocide case, against Israel. Your final comments?

MAHMOOD MAMDANI: Well, for those who read the South African application, it must be clear that its strong point was the content, the argument, the substance. The empirical material relied, drew totally from U.N. sources and from no other source, really. So it was unimpeachable.

The Israeli side, the Israeli lawyers did not say anything, did not present any defense on whether a genocide is unfolding. What they did defend was that, procedurally, South Africa should not be the party making an application.

AMY GOODMAN: Well, Mahmood Mamdani, we’re going to continue this discussion and post it online at democracynow.org. Mahmood Mamdani, professor of government at Columbia University, and Katherine Franke, Columbia Law School professor. I’m Amy Goodman. Thanks for joining us.