by Aaron Rabinowitz

Haretz

Jan 31, 2024

https://www.haaretz.com/israel-news/202 ... 7bdb670000

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

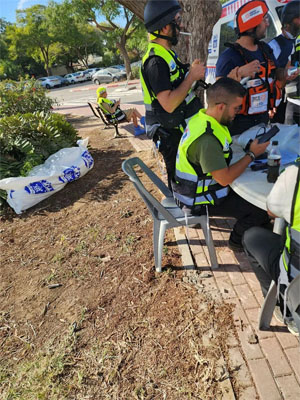

Zaka volunteers at Be'eri in October. The subjects have no connection to the content of this article. Credit: Olivier Fitoussi. Graphic: Masha Zur Glozman

A group of people sit around a plastic table, taking shelter under the branches of a tree on a hot day. The atmosphere is relaxed, and the conversation flows. Some smoke cigarettes, while others sip soft drinks and nibble on snacks. A young woman is perched on a nearby bench, engrossed in her phone. The environment is pastoral in God's little acre.

Even the body on the ground next to them, wrapped in a white plastic bag, doesn't disturb the scene. It's not external to the story; it's a part of it.

This moment took place in Kfar Azza early in the second week of the war against Hamas. The group sitting among the burned houses and devastation consists of some 10 volunteers from the Jerusalem branch of Zaka, the ultra-Orthodox organization that retrieves human remains after attacks and disasters. The white body bag is marked with the organization's logo.

"It was just bizarre that there was a corpse right there next to them, and they were sitting around, eating, and smoking," said one of two volunteers from a different organization who were present. "It's unbelievable."

The non-Zaka volunteers asked them why they weren't transferring the body into an ambulance or the refrigerated truck parked across the road. They replied indifferently that it would be taken care of later and returned to their diversions.

Approaching the group a little more closely revealed that three of the Zaka volunteers were making video calls and videos for fundraising purposes. According to the non-Zaka observer, the body was part of a staged setting – an exhibit designed to attract donors, just when the race against time to gather and remove the bodies of victims of the massacre was most urgent.

"They opened a war room for donations there," said another witness to the event, who has worked throughout the war in the Gaza border communities attacked on October 7. "Two weeks later, I saw them acting similarly in Be'eri as well – sitting and making videos and fundraising calls inside the kibbutz."

Zaka responded to this description with a statement saying that "No fundraising calls were made on the ground on behalf of the organization, and if any specific incident is brought to our attention, we will examine and deal with it."

A Haaretz investigation raises several questions about procedures during the retrieval of the bodies. It is based on the accounts of military personnel present at the body retrievals and the Shura military base (which was made a body identification center), as well as volunteers from Zaka and other rescue organizations who worked in the border communities.

It's clear that hundreds of Zaka Jerusalem volunteers did important work by collecting victims' bodies under challenging conditions. At the same time, some of the organization's activities – which, on the eve of the war, was entangled in debts of millions of shekels – were directed towards fundraising, public relations, media interviews, and tours for donors.

Zaka volunteers work on fundraising as a body lies nearby.

In the first and critical days of the war, the IDF decided to forego the deployment of hundreds of soldiers specifically trained in the identification and collection of human remains in mass casualty incidents. Instead, the Home Front Command chose to use Zaka, a private organization, alongside soldiers in the Military Rabbinate's search unit, known by the acronym Yasar, for the south.

More personnel were necessary, but when the soldiers of the Military Rabbinate's search unit in the north and the Home Front Command's unit for collecting fallen soldiers reported for reserve duty on October 7, they were told they had to wait.

"I have no explanation for why they didn't deploy [the Home Front Command's unit] and our people from the north," says an officer in Rabbinate's southern search unit.

Officers at the Shura base were also unable to explain why the military didn't deploy the personnel who had already been called up, all of them combat soldiers who knew how to operate under fire. An officer in the Home Front Command's unit said that his commanders "begged" senior leadership for their deployment but were rebuffed. It wasn't until the second week of the war that these soldiers began to operate in the area – and even then, not fully.

In the meantime, Zaka volunteers were there. Most of them worked at the sites of murder and destruction from morning to night. However, according to witness accounts, it becomes clear that others were engaged in other activities entirely. As part of the effort to get media exposure, Zaka spread accounts of atrocities that never happened, released sensitive and graphic photos, and acted unprofessionally on the ground.

There was a price for choosing Zaka, say sources at Shura. "We received bags of theirs without documentation, and sometimes with body parts that were unrelated to one another," says an officer in the camp. Such problems made the identification process very difficult, he says. Some bags came many days after the outbreak of the war, he adds.

One of the volunteers who worked at Shura says: "There were bags with two skulls, bags with two hands, with no way to know which was whose."

Zaka volunteers clean a home in southern Israel after it was attacked. Someone who toured the area with Zaka says he saw remains in buildings marked as cleared.Credit: Zaka

In the following weeks, several hundred cases remained: bags with body parts that had been collected belatedly and which needed to be matched to victims. Some were still unknown as of the time of writing this article. A volunteer from Zaka Jerusalem who serves in the Military Rabbinate says there was a noticeable difference between the professionalism of the soldiers and the Zaka volunteers.

"We arrived at the scene at the beginning of the war, and there was not a body or find in the field that we did not properly document," he says. "Zaka barely wrote anything on the bags, and you can forget about any documentation." The same soldier-volunteer pointed an accusing finger at the military, which assigned the task to Zaka.

However, it wasn't only Zaka personnel who caused problems. An officer in the Military Rabbinate's search unit said that initially, his personnel also failed to record where each body was taken from, which further delayed identification.

"At first, it wasn't possible to document [everything] because the workload and the pressure were immense," he says. "But we worked systematically, and later we were asked to do a retrospective reconstruction of our work."

Later, when bags from the military arrived, the difference was obvious, says a volunteer who worked at the base. "It was obvious that more thorough work was done there," they say.

Home Front Command soldiers and volunteers from other organizations described negligent work by Zaka in other aspects as well. According to them, on numerous occasions, they approached vehicles and houses with a Zaka sticker stating that the place had been cleared of body parts when that wasn't the case.

Body removal in Ofakim on October 8. Hundreds of Zaka volunteers did important work by collecting remains under difficult conditions.Credit: Ilan Assayag

"Zaka took part of a body and left the other part in the same house," says a volunteer at Shura. Someone who toured the kibbutzim of the area with Zaka said that, together with members of the organization, he entered houses that had been labeled as cleared, yet he saw human remains in them.

There are more examples. In the parking lot that was set up in the moshav of Tkuma, where vehicles that were damaged in massacres on roads and near the music festival in Re'im, uncollected body parts were found. "We found parts of bones and other parts there," a Home Front Command soldier says. "A lot of people here are angry, [asking,] 'Why did you train us for this, and on the day of reckoning, you didn't let us do the job?"

Even when the soldiers began working, during the second week of the war, they were sent to collect the bodies of terrorists and transport them to the Sde Teiman base in Be'er Sheva. They were also tasked with handling the scenes of attacks on military facilities.

Zaka personnel handle a destroyed vehicle after the Hamas attacks. According to a soldier, remains were found that Zaka had failed to locate. Credit: Zaka

"We asked the commanders why they weren't letting us enter, and each time we got a different answer," says a soldier. "One time they told us, 'You've been trained for earthquakes.' Another time, they said they didn't want to risk the lives of soldiers, and yet another time they explained to us that the commanding general gave [the mission] to the IDF's national rescue team, one of whose members is also a senior member of Zaka."

He adds: "Had we worked the way they taught us, we could have spared many people unnecessary suffering [and] bring [the victims] to burial much sooner." Several Zaka volunteers admitted to Haaretz that the work would have been better, faster, and more precise had the soldiers worked alongside them.

The power of the vest

Throughout the first days of the war and afterward, uniformed soldiers from the Home Front Command appeared repeatedly in the media. But over their uniforms, they wore non-IDF vests on which the name "Zaka" was emblazoned. Military officers who were informed about this blaring detail could not account for it.

Haim Outmezgine, head of Zaka's "special forces," serves in the reserves in the Home Front Command's rescue unit and is one of the senior officials who appeared in this outfit frequently – and not only on the screen. Toward the end of October, with the organization's members still working in the kibbutzim, he starred in a staged, elaborate music video in which he was recorded out in the field.

The Shura military base, where bodies were gathered for identification purposes, in October. A volunteer says that in one case, Zaka collected part of a body and left the rest at the scene. Credit: Naama Grynbaum

In the video, he and his son sing a song he wrote himself. The video is accompanied by subtitles that aim to tug at the heartstrings as well as the pocket.

"Hundreds of Zaka volunteers left behind a supportive family and went out devotedly, and were exposed to the terrible atrocities that took place in the south, and they return home with a sack overflowing with emotions. You are welcome to salute them," reads the video description, alongside a link for donations.

Speaking with Haaretz, Outmezgine said that he produced the music video privately and that the organization later decided to use it for the fundraising campaign. He said that filming and producing the music video did not take much time: "I wrote it on Friday, I recorded it in the studio on Saturday night, and a day or two later the music video was filmed."

Outmezgine wasn't just part of Zaka Jerusalem's media campaign. According to some sources, he also played a central role in the association between the organization and the IDF and was in command of several sites starting from the evening of the attacks – mainly in the area of the party in Re'im, Kfar Aza, and Be'eri. About a month after the start of the war, Outmezgine blocked a volunteer from a rival organization from entering Be'eri, even though the volunteer had received orders from an officer.

Last edited 7:38 AM · Nov 3, 2023

Outmezgine confirmed that he blocked him, saying he had thought he was an impostor. A source at Zaka Tel Aviv (another competitor) also said that members were blocked by Zaka officers when they tried to reach the area. "They specifically told us that Haim [Outmezgine] said they didn't need us there," says the source.

This raises the question: What is the relationship between the Home Front Command's rescue unit and Zaka Jerusalem? The answer, it appears, is Outmezgine, who is not only a reservist in the unit but also considered very close to its commanders.

A Zaka volunteer who is closely acquainted with him says it was Outmezgine who was behind the unit taking command of the attack sites – and behind the use of Zaka. "He is the one who has the power to tell the commanders, 'This is our case,'" says the volunteer. He adds with a half-smile: "The other volunteers couldn't enter because it's a closed military zone."

A house in Kfar Azza about a month after it was burned on October 7. Some Zaka volunteers admit the work would have gone better had they worked alongside the military.Credit: Eyal Toueg

Outmezgine describes the matter similarly. "I understood that we were in a race against time," he said in an interview with Arutz Sheva, a settler radio station. "I called my commander, Col. Golan Vach, and I said that this was our mission."

Indeed, the Home Front Command officially took control of the attack areas, and its operational arm, especially during the first week, was Zaka. Outmezgine says an agreement exists between the IDF and Zaka that allows the operation of the organization in the field.

A clue to Outmezgine's personal operating procedures may be found in at least one incident in which he took a bag of materials collected at an attack scene and brought its contents to the courtyard of his home for "private examination." Military sources who were informed of this saw it as a grave matter and couldn't say who had authorized it. Outmezgine, for his part, says this was a one-off incident that he's proud of. "That was a bag with garbage that I could have left in the field, but I took responsibility," he says.

Historical rivalry

Generally, conflict between organizations working to gather human remains from the sites of attacks, accidents, and disasters in Israel is nothing new. Neither is what stands behind it: money, and a lot of it. Tens of millions of shekels are allocated to this mission through donations and financial support from the state.

Today, there are three main organizations in the field: Zaka Jerusalem, Zaka Tel Aviv, and the 360 Unit organization. Over the years, competition between them has caused more than a few problems in operations – for example, distributing graphic photos that failed to respect the dignity of the deceased. This reached the point that two years ago, the police introduced a new directive on the procedure for collecting remains to regulate the process.

According to the procedure, only those who volunteer with the police and wear a police vest are allowed to work at the scene of an incident. As part of this regulation, volunteers are required to undergo training, are subject to a clear hierarchy with the police, are prohibited from being interviewed without authorization, and are barred from releasing details or images from the scenes.

It appears that all the rules have been broken since October 7. Videos and graphic photos from the horrific sites filled Zaka Jerusalem's social media accounts: rows of bodies in bags, bloodstains, and much more. These posts had a common denominator: pleas for fundraising.

The timing was critical. Before October 7, the organization faced insolvency. In the time since, says a source at Zaka, they have raised over 50 million shekels ($13.7 million).

Haim Outmezgine receives a commendation from the IDF in 2022. He says there is an agreement between Zaka and the military allowing it to work. Credit: Zaka

Meanwhile, throughout the duration of the war, and despite the race against time to collect bodies, volunteers from the organization have arranged private tours for donors. Civilians, however, haven't been allowed to enter the border areas, defined as closed military zones.

Someone who organized such a tour says a senior Zaka volunteer organized it and took the participants into Be'eri. "He met us at a nearby gas station, gave us and the donors Zaka vests, and that's how we entered, with two vehicles," he says. Haaretz has obtained a recording in which a Zaka volunteer coordinates a similar tour.

Zaka says all the tours were coordinated with the relevant authorities and were done with permission. "Many donors request guidance and explanation from Zaka personnel in order to connect to the terrible disaster," read a statement from the organization.

"The Zaka organization was asked by the National Information Directorate [in the Prime Minister's Office] to take part in informational activity for both donors and opinion leaders worldwide and sees these tours as part of the country's efforts to achieve victory in public opinion, too. The Zaka organization also accompanies donor tours for the benefit of the kibbutzim and their reconstruction, seeing it as a privilege and an honor."

The fundraising issue

The fundraising started on October 8. A tweet on the organization's account the day after the attacks in the south read: "Our volunteers in the field are surrounded by slain bodies and artillery fire and urgently need protection and equipment." The statement was, of course, true – Zaka personnel did indeed work under fire, needed additional equipment, and were surrounded by bodies.

Although raising funds for an organization is a completely legitimate act, its timing and how it was done raise concerns. These concerns are certainly not diminished by the fact that Zaka hired the services of a public relations office that, already in the first weeks of the war, accompanied and photographed the volunteers.

Volunteers from the 360 Unit and Zaka organizations on October 7. The rivalry between organizations has caused problems for years.

From the second week of the war, Zaka began to be paid by the Defense Ministry, alongside the appeals for public donations. An agreement had been reached between the ministry and the organization, according to which Zaka would receive 500,000 shekels for cleaning houses, vehicles, and public bomb shelters damaged in the attacks.

According to the ministry, the organization committed to cleaning 500 structures. Zaka says that this payment financed only part of the expenses and that "it is a unique assignment that required the purchase of dedicated equipment for the sake of the mission… [and] the transportation and mobilization of hundreds of volunteers."

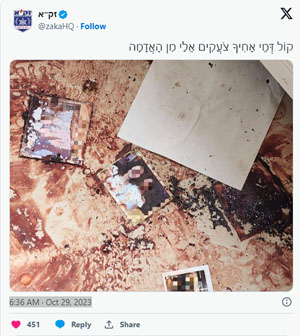

The fundraising campaign has continued to escalate. An October 29 post on X showed family photos stained with blood from one of the scenes, along with the caption: "The voice of my brothers' blood cries out to me from the ground."

This was just part of the activity that went on while many body parts still awaited identification and burial, a process that was mostly completed only about 50 days after the start of the war. Even now, findings and body parts are still being discovered.

7:29 AM · Oct 8, 2023

At the attack scenes, the question was not only what to photograph but also what exactly to show. In some cases, volunteers from Zaka were seen wrapping bodies already wrapped in IDF bags. The new bag prominently displayed the Zaka logo.

"We wrapped the body in a body bag, and a few minutes later, a Zaka team arrived," a volunteer from another organization says. "The team leader, a senior member of the organization, wrapped the body in a Zaka bag. Why did they do that? Everyone knows that there are public relations matters here."

Several officers and volunteers who worked at the Shura base told Haaretz that many bodies arrived wrapped in two bags – the military one and a Zaka one covering it. According to an officer in the Military Rabbinate, this was the case for dozens of bodies, which complicated the work.

"The second we saw a Zaka bag, we transferred the body to the civilian unit at Shura," he says, "but they would open it there and would then have to transfer it to the military unit." According to Outmezgine, these actions were taken because the military bags were defective. Officers in the Military Rabbinate denied that there were problems with IDF's bags. "It's interesting that we didn't have any problems," they said.

It's not unprecedented for Zaka personnel to have switched bags or added their own. Haaretz has a string of documentation and accounts of similar activities by the organization's volunteers who arrive at the scene of a murder, accident, or suicide. Zaka denied the claim of changing or covering bags and said that double bags had been used only when the first one was damaged.

Tales of imagination

"We saw a woman, around 30 years old, [and] she was lying on the floor in a large puddle of blood, facing the ground," said a Zaka volunteer tearfully in an account posted on Zaka's social media accounts. "We turned her over in order to place her into the bag.

"She was pregnant," he added and stopped to take a breath. "Her stomach was swollen, and the baby was still attached by the umbilical cord when it was stabbed, and she was shot in the back of the head. I don't know if she suffered and saw her baby murdered or not."

6:36 AM · Oct 29, 2023

This horrific incident, which the Zaka volunteer alleged occurred in Be'eri, simply didn't happen, and was one of several stories that have been circulated without any basis. There is no evidence for this incident, and no one in the kibbutz has heard of this woman. A Zaka senior official admitted in a conversation with Haaretz that the organization knows the incident didn't occur.

In another video, which features the same volunteer, he describes, weeping, how he found the burnt and mutilated bodies of 20 children in one of the kibbutzim. He told Haaretz that this was behind the dining hall in Kfar Azza, while in another instance, he said it was in Be'eri.

However, the children who were killed in Kfar Azza are Yiftach Kutz, 14, and his brother, Yonatan, 16. Ten children were killed in Be'eri, but at least some were known to have been with a parent and were killed in their homes.

The organization has been accused of spreading false information before. In December 2022, Haaretz reported that Zaka had inflated its stated number of volunteers for years in order to receive more funding.

In response to a request for comment, Zaka said: "Collaboration between Zaka and emergency agencies takes place in usual times and in emergencies, based on the coordination of expectations and early planning. Zaka volunteers operated in close and full coordination with the responsible bodies in the field. Collaboration is not a conflict of interests but a joint effort.

"Zaka is a voluntary organization funded by donations, and the war has led Zaka to have massive expenditures for equipment and supplies," the organization continued. "The presence of Zaka personnel on the front lines … provided an opportunity for the public to be shown the organization's activities, which are also carried out during non-emergency times, privately."

Body retrieval in Be'eri. Zaka volunteers have organized private tours for donors while the site is a closed military zone. Credit: Zaka

For its part, the military said in response to a request for comment: "Following the events of October 7, an operational system was established, headed by an officer with the rank of colonel, to lead the search and retrieval mission in the Gaza border region. Due to the complexity of the mission and the scope of the casualties, the Defense Ministry contacted Zaka to receive assistance and reinforcements for this mission.

"Among the units that participated in the military effort was the search unit of the Military Rabbinical Corps. [Home Front Command] units were recruited in full in the first two weeks of the war. The IDF will conduct a detailed and thorough investigation, including regarding the mobilization of personnel, to clarify the details completely when the operational situation permits and will publish its findings to the public."