CHAPTER TWO: What Is the Long War?To understand and describe how the current long war might unfold in the coming years, it is first necessary to understand what the long war actually is. Since no definition for the long war has been widely accepted, in this chapter we review recent uses of the term and propose our own definition of long war.

While we feel that our definition accurately characterizes the current long war in a fair and politically uncharged manner, we do not use it exclusively in the rest of the report. To broaden the applicability of this report to cover a range of potential future trajectories, we sometimes introduce modified definitions of long war that are appropriate to the future scenario described.

Background and Use of the Term “Long War”General John Abizaid brought the term “long war” into prominence in 2004 while he was commander of USCENTCOM. “Long war” was solidified as a term of art through its inclusion in subsequent books (Carafano and Rosenzweig, 2005), the President’s January 2006 State of the Union address, and especially the 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review (QDR). In these documents, the term is used to refer to current U.S. actions against al-Qaeda and its manifestations.

The 2006 Quadrennial Defense Review spoke at length about a long war the United States is currently engaged in, and opened with the line: “The United States is a nation engaged in what will be a long war” (DoD, 2006). In the QDR, the term “long war” emphasized the war’s duration and was chiefly used in regard to the set of actors that the United States faces, who are often characterized as “violent extremists” or “terrorists.” Not much attention was paid to the connection, if any, between particular groups that may be involved in the long war. In the QDR, four main points are made regarding winning the long war. They are as follows:

• defeat terrorist networks

• defend the homeland in depth

• shape the choices of countries at strategic crossroads

• prevent hostile states and nonstate actors from acquiring or using WMD.

While each objective is clearly relevant for national security, the QDR does not explain how, or whether, these objectives are unique to the long war. Indeed, the reference to “countries at strategic crossroads” is historically used to denote well-known states such as China and Russia; however, despite the importance of these states within military planning, they are not directly linked to the long war. Also, in describing the strategy for winning the long war, the QDR says little about the theory of victory. The QDR provides little to go on in terms of “winning” in the long war, or “defeating decisively” the threat that the United States faces.

The description of the long war in the QDR provides little guidance on how this war might unfold into the future. To explore this issue, the Army, in cooperation with Joint Forces Command and Special Operations Command, held workshops in support of the Unified Quest 2007 wargame to describe what the long war is. One of the first workshops, held in late 2006—the Nature of the Long War Seminar or NLWS—provided multiple definitions from panel members to help spur discussion. One definition focused on “protracted conflicts involving episodes of intense armed violence interspersed with tense peace or low intensity conflict.”1 Other definitions, specifically addressing indi- vidual components of the long war, aided in articulating the individual components that drove the nature of the long war in its many guises. However, while many definitions met with general approval, no single definition emerged that was broadly accepted.

Definitions of the long war often bear similarities or include concepts relevant to other U.S. national strategies, including the National Strategy for Combating Terrorism (NSCT). The NSCT begins with a statement made by President Bush not long after 9/11:

No group or nation should mistake America’s intentions: We will not rest until terrorist groups of global reach have been found, have been stopped, and have been defeated. (President George W. Bush, November 6, 2001) (The White House, 2003, p. 1)

This statement specifically calls attention to the “global reach” of the terrorist groups that the United States is most interested in, thus implicitly making a distinction between these groups and local and regional terrorist organizations that do not have, and that in many cases do not even desire, global reach. The discussions of the long war in the QDR draw a similar distinction between groups with and without global reach.

Similarly, the U.S. National Security Strategy (NSS) speaks of the global nature of terrorism and the importance of using a full suite of national power to combat it:

To defeat this threat we must make use of every tool in our arsenal—military power, better homeland defenses, law enforcement, intelligence, and vigorous efforts to cut off terrorist financing. (The White House, 2002, pp. iii–iv)

The NSS goes on to mention the temporal aspect of this set of challenges: “The war against terrorists of global reach is a global enterprise of uncertain duration.” This statement is in concert with the discussion in the QDR and indicates directly the difficulty in knowing the duration of the war, while also indirectly committing U.S. efforts to last longer than might be expected.

A growing dissatisfaction with the term “long war” itself has been evident in many discussions waged in political circles. A recent memo released by the House Armed Services Committee (Conaton, 2007; Maze, 2007) reiterates the colloquial understanding of the term long war when it asks that such terms be “removed” from future legislation. In March 2007, Admiral William Fallon, upon taking over command of CENTCOM from General Abizaid, asked that the term be dropped from the military lexicon to emphasize the U.S. military’s desire to reduce U.S. forces in the region over time, although the military would continue to conduct operations more broadly against the threat (Lardner, 2007).

Other terms have been suggested as potential replacements for the long war. In April 2007, General George Casey, after becoming Chief of Staff of the Army, offered the term “persistent conflict” as a potential descriptor for the types of operations the United States would be using to combat al-Qaeda and associated movements (Scarborough, 2007). This term is particularly pertinent to the time component of expected operations in Iraq and elsewhere—the term emphasizes how long U.S. operations in the region would be conducted, perhaps in preparation for longer-than-normal deployments.

Despite the controversy over the term “long war,” it still has supporters. Some in the joint community use the term to describe current operations. While discussing Iran’s contribution to current operations in Iraq and Afghanistan with the former Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Michael G. Mullen, General James T. Conway said the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan are not single events, but part of a larger set of battles associated with the long war. He noted that the term long war “precisely describes what this nation is going to be engaged in, for probably the next couple of decades” (Grogan, 2007). Admiral Mullen has also used the term to denote both the duration and the breadth of actions that will be necessary to address current security issues in the Middle East.2

While a clear and unambiguous definition of the long war has thus far been elusive, many have tried to define the term through analogy, often drawing upon historical examples. The long war has been considered as being somewhat akin to long-duration metaphorical wars such as the “war on drugs” and the “war on poverty,” albeit without significant consensus or expansion. While all of these terms are somewhat vague and politically charged, they nonetheless describe real-world threats to the United States, the existence of which few would dispute. Similarly, major works such as Samuel Huntington’s “Clash of Civilizations” (Huntington, 1993), have also been cited as an overarching descriptor of the current long war. In many of these cases, the parallels with the long war have not been discussed beyond superficial anecdotes, and some may warrant further exploration.

Some argue that there will always be an ideology that confronts the dominant power of the time—from the anarchists in the early 20th century to Nazism and communism and now Islamic extremism. These ideologies attract individuals who are disaffected with the status quo even if they do not necessary subscribe to the ideology in full. The most frequently cited analogy used in reference to the long war is the “Cold War,” with the ideology of communism used as a parallel to some fanatical form of Islam.

Behind this understanding of the long war lies the belief that the collective thinking on communism pulled groups of people together much like the violent ideologies espoused by such groups as al-Qaeda.3 Once again, however, those who draw comparisons between the Cold War and the long war have typically not linked specific operations, policies, and mechanisms of the Cold War to the act of confronting al- Qaeda and its manifestations or to current unrest in the Middle East in general. It is also clear that communism, at its height, commanded a set of resources well beyond the scope of the current, or any plausible future, long war adversary. In sum, therefore, such comparisons must be made cautiously so as not to overstate the current threat.

Carafano and Rosenzweig (2005) provide an example of the kinds of parallels that may be drawn between the Cold War and the long war. In this book, the authors draw broad lessons for the current conflict from the Cold War, despite the differences in the actual threat. These lessons include the need for “sound security, economic growth, a strong civil society, and a willingness to engage in a public battle of ideas,” all hallmarks of Eisenhower’s policies during the Cold War. The authors note further that the long war, like the Cold War, “takes time,” and whether looking back on the 40 years of the Cold War, or further back to World War I (thus linking fascism and communism against democracy as did Bobbitt (2002)), the United States will have to prepare for a multiyear event. Finally, the authors emphasize that “Now is the time to get it right,” i.e., in both situations, a clear policy and strategy are needed to confront the threat and provide the guidance to generate the actions to be taken. Carafano and Rosenzweig rightly speak to the “systems view” of the problems currently being faced by the United States, an emphasis we will take up in this report.

Notwithstanding the thrust of this study, defining the struggle against terrorism is not within the Department of Defense’s exclusive competence, much less the U.S. Army’s. Any eventual and agreedupon definition must reflect a national consensus of what the effort is and what it is not. The national definition must take into account the views of all who are involved in the struggle, to include other agencies of government, the legislative branch, the national security intellectual community, industry and corporate America, and the informed public. The multiparty discourse required to reach such a consensus definition has yet to occur.

A Synthesis Description of the Long War: The Confluence of Governance, Terrorism, and IdeologyThis report is concerned with the attention given to three areas in describing the current situation facing U.S. forces, namely, those related to the ideologies espoused by key adversaries in the conflict, those related to the use of terrorism, and those related to governance (i.e., its absence or presence, its quality, and the predisposition of specific governing bodies to the United States and its interests). How the U.S. forces and U.S. national means writ large address each of these issues is still largely to be determined. Thus, paraphrasing the Cold War analogy, getting the starting point “right” and setting the strategy for the long war are still largely unaddressed, if they are not contained in already articulated policies of combating terrorism and other national strategies.

Others have written about the shortcomings of using the Cold War analogy for describing current threats facing the United States. These include John Tirman at the MIT Center for International Studies.4 Air Force General Richard B. Myers has also distinguished between the current struggle and the long war:

It’s not like the Cold War, where we knew what the enemy’s capabilities were; we kept pretty good track of that. Their intent was always the question mark. Now we are in the 21st century security environment, and we know what the intent is; that question mark has gone away. Capabilities is the issue.5

The RAND Arroyo Center team has been engaged in various discussions, both internally and externally (with our sponsors and through Unified Quest), on the topic of the long war, all of which have highlighted the difficulty of producing a single term capable of describing the complex nature of the situation facing the United States. Indeed, so many terms have been bandied about, it is clear others are struggling with an overarching term as well. Nonetheless, even though the term “long war” is being supplanted and will possibly even be removed from formal military writing, we find it useful to study the construct in relation to the three key issues of governance, terrorism, and ideol- ogy, particularly to understand how these concepts coalesced to foster an attack such as 9/11.

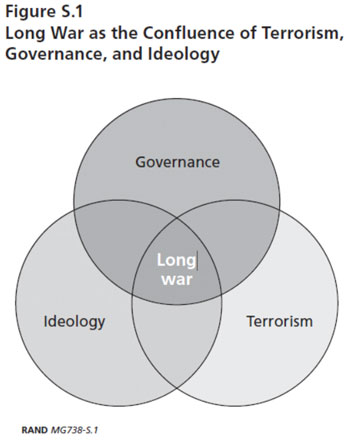

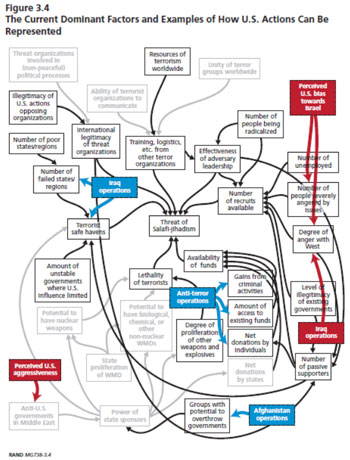

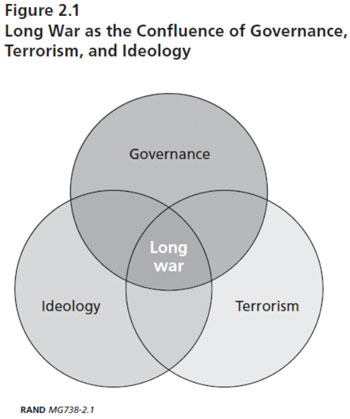

The elements of the long war currently being discussed by policymakers, military leaders, and others are not without merit. Individual and group violence, the proliferation of dangerous and violent ideologies, and destabilization of government and government control—all are currently in play. However, the most common misconception of the long war has been the attribution of one of these as being more important than the others. Equating the long war to just terrorism or just an “ideological struggle” does not do it justice and can perhaps be counterproductive in the effort to define the strategies and operations necessary to meet national goals. Definitions that address one of the components over the others miss the impact that this long war has had, which is: the confluence of governance, terrorism, and ideology (GTI) makes this long war complex and difficult, and is what differentiates it from other struggles the United States might be involved in.

The goal of this report is not to determine which one of the three is the key problem. Indeed, much empirical research has focused on the particular drivers of conflict in an attempt to pinpoint specific underlying causes and prioritized effects. Instead, we take the stance that the biggest, and perhaps most likely, pitfall U.S. forces will encounter in preparing and considering the implications of the long war is to focus too much attention on one area without due consideration of the effects of the other two. While the United States may have many individual successes in tracking down terrorists abroad, shoring up individual governments, or discounting ideologies, a concerted effort across all three domains will be necessary to ensure that this long war follows a favorable course.

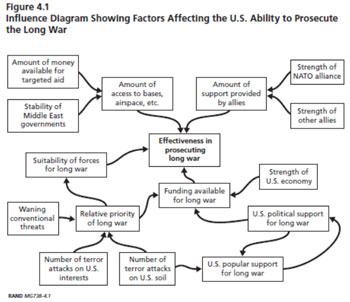

One means of thinking through the problems the United States faces is to consider the long war as the confluence of those three problems— those associated with terrorism, those associated with governance, and those associated with ideologies (see Figure 2.1). Each area has a long history of concern for the United States.6 Splitting up the components and then recombining them to understand the overall issues involved helps to differentiate what is “in” and what is “out” of the long war.

Figure 2.1: Long War as the Confluence of Governance, Terrorism, and Ideology

RAND MG738-2.1

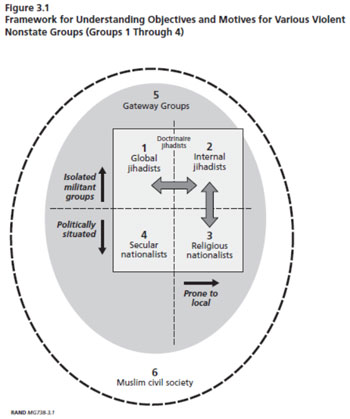

As shown in Figure 2.1, there are regions where only two of the three factors overlap, such as the overlap of terrorism and governance, so that the resulting situation, while potentially important to U.S. national security, is not part of the long war, which, according to our construct, involves all three elements. Fighting Hezbollah, for instance, is related to governance and terrorism but does not involve an ideology that, at the moment, directly threatens the United States. Thus, actions against Hezbollah are not a primary element of the long war in our GTI construct. This is not to say the issue does not warrant attention; in fact, we will describe later that for various reasons the struggle against ideologically motivated groups like Hezbollah has important implications for the long war depending on actions taken by both Hezbollah and the United States. While Hezbollah is not included in our current construct since it does not fall into the GTI construct, it may eventually be, depending on how the future unfolds.

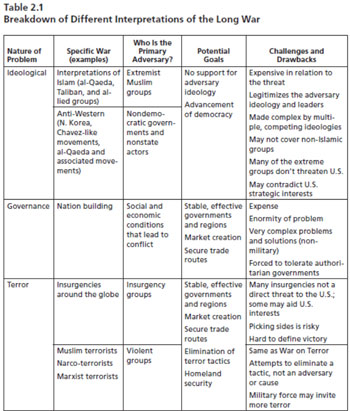

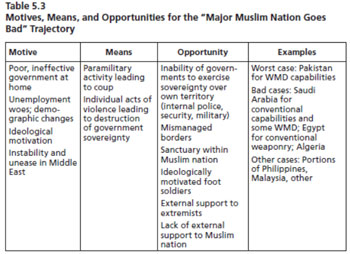

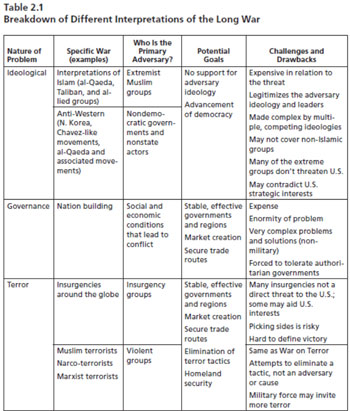

Table 2.1 breaks down the components of the long war in terms of the nature of the problem, primary adversary, potential goals, and challenges and drawbacks. The items refer to our thesis that the current set of problems in the long war represents a confluence of GTI issues. In some cases, such as when a country participates in nation building to foster good governance, there may not be a person, group, or state that constitutes the adversary. Rather, the “adversary” would be the underlying economic and governmental conditions that create societal disharmony.

It is possible that some of the broad definitions of the long war may end up looking narrow when strategies are actually implemented to address the problems. For example, a broad ideological definition could result in something akin to a very narrow counterterrorism campaign when implemented. In those cases, some of the benefits in the way that the war has been described may be garnered up front in the way the long war mobilizes domestic constituencies at home and provides a central idea to rally around. Some of these interpretations will most likely need additional strategies articulated to best address them; others may already be contained in current U.S. security strategies.7

In this report, we are interested in understanding the intersection of these three areas that construe our interpretation of the long war. As mentioned above, we propose in this report that the long war cannot be described in one simple tagline, but rather constitutes a collection of issues associated with GTI. The breakdown in Table 2.1 gives many references to other potential GTI problems that U.S. forces might be facing, and potential drawbacks to choosing one interpretation (versus a focus on all three problems) on which to base a U.S. strategy.

Table 2.1: Breakdown of Different Interpretations of the Long War

Nature of Problem / Specific War (examples) / Who Is the Primary Adversary? / Potential Goals / Challenges and Drawbacks

Ideological / Interpretations of Islam (al-Qaeda, Taliban, and allied groups) -- Anti-Western (N. Korea, Chavez-like movements, al-Qaeda and associated movements) / Extremist Muslim groups -- Nondemocratic governments and nonstate actors / No support for adversary ideology -- Advancement of democracy / Expensive in relation to the threat -- Legitimizes the adversary ideology and leaders -- Made complex by multiple, competing ideologies -- May not cover non-Islamic groups -- Many of the extreme groups don’t threaten U.S. -- May contradict U.S. strategic interests

Governance / Nation building / Social and economic conditions that lead to conflict / Stable, effective governments and regions -- Market creation -- Secure trade -- routes / Expense -- Enormity of problem -- Very complex problems and solutions (nonmilitary) -- Forced to tolerate authoritarian governments

Terror / Insurgencies around the globe -- Muslim terrorists -- Narco-terrorists -- Marxist terrorists / Insurgency groups -- Violent groups / Stable, effective governments and regions -- Market creation -- Secure trade routes -- Elimination of terror tactics -- Homeland security / Many insurgencies not a direct threat to the U.S.; some may aid U.S. interests -- Picking sides is risky -- Hard to define victory -- Same as War on Terror -- Attempts to eliminate a tactic, not an adversary or cause -- Military force may invite more terror

As an example, an ideological description designating “extremist” Muslim groups as the primary problem facing the United States might imply the goal of reducing or eliminating support for the ideology and advancement of democracy in its place. In this case, using ideology alone as the basis for action creates a number of challenges. First, many of what are often termed “extremist” groups are not actively engaged in anti-Western efforts. Thus, calls for fighting “extremist” Muslim groups incur considerable expense relative to the threat those groups pose. The designation also creates problems of ascription. Limiting the ideological basis to only Muslim groups excludes any secular or nationalistic groups that may be more threatening. At the same time, aggregating all groups under an umbrella term “extremist” conceals the variegated goals of individual groups and nuances that any U.S. response will have to address. Examples of the challenges in simplifying the description of the long war to issues of governance or terrorism are also given.

Ideology in the Current Long War8The primary adversary in the current conflict begins with the one that attacked the United States on September 11, 2001, causing nearly 3,000 deaths. Usama bin Ladin and the terrorist organization al-Qaeda are enemies of the United States. However, there is more to this “long war” than simply fighting a particular terrorist group. If we start with the ideology espoused by al-Qaeda, to include those who believe as Usama bin Ladin does, we can start to discuss the anti-Western and violent ideology of al-Qaeda: Salafi-jihadism (SJ).9

In this hyphenated phrase, “Salafi” refers to Salafism, an Islamic revival movement that began in late 19th century Egypt,10 which has since come to function as an umbrella term for a number of fundamentalist groups—only a portion of which advocate violent activities. Early Salafism portrayed Muslims as having lost their way in the modern era, and holds that only through a return to the practices of the first generations of Muslims (the “Salaf”) could Islam renew itself and, at the same time, come to terms with modernity. Roughly half a century later, another group was to redirect the fundamentalist orientation of Salafism. Hassan al-Banna and Sayyid Qutb of the Egyptian Muslim Brotherhood rejected Western liberal influences and injected a more extreme understanding of Islam into Salafism. This thread met with Wahhabism, an older movement that also rejected modernism and emphasized the tenets of jihad (holy struggle) and takfir (declaring another Muslim an infidel),11 in 20th century Saudi Arabia. In the 21st century, a number of self-declared “Salafi” groups exist, both violent and nonviolent, which argue with each other over who represents true Islamic practices. Thus Salafism is not well bounded in the sense that there is near-constant debate regarding who is truly Salafi and who is not. For instance, some groups describe others as “Qutbist,” an epithet in Islam because it suggests that the targeted practitioners worship a man, not the true religion.

Consequently, Salafi-jihadism is a hybrid of sorts, because it rejects traditional understandings of Islam along the lines of early Salafism, while accreting the innovations of Qutb and Wahhabism in disdaining the West and proclaiming the prominence and acceptability of jihad and takfir.12 Operationally, Salafi-jihadism sees American policies as especially implicated both in introducing foreign norms into Muslim culture and in creating a system that oppresses Muslims. The only way to confront the American threat is to take up arms, establish an Islamic emirate, and wage war against the West and its Muslim allies (not necessarily in that order).

It is not true that groups other than Salafi-jihadists do not threaten the United States.13 The focus of many groups on local issues rather than attacking the United States directly leaves them outside of having specific U.S. strategic importance. These local issues may sometimes concern the United States, especially those affecting Middle East stability, but they are not directly justifying action. Nonetheless, some of these groups may act to support the aims of the SJ groups at the center of this long war, either directly or indirectly, and, over time, may eventually be implicated in direct U.S. action based on those actions.

Governance in the Current Long War14The concept of governance appears as a central component in the 2006 QDR. The QDR views good governance as a key influence in reducing “the possibility of failed states or ungoverned spaces in which terrorist extremists can more easily operate or take shelter” as well as “opportunities for terrorist organizations to acquire or harbor WMD.”15 To understand how good governance creates such effects, it is useful to know what governance means. According to the United Nations, governance is the “process of decision-making and the process by which decisions are implemented (or not implemented).”16

When a group needs to accomplish certain ends, it develops a process to decide how to reach that end, and then decides how to implement that decision. Governance therefore corresponds to some level of social organization; a situation without any type of governance could be seen as chaotic or anarchic. In some systems, governance is more straightforward—a single individual, or small cadre of individuals, decides, and the decision is carried out by whatever governing apparatus has been established. In other systems, particularly in open, democratic systems, governance can be messier and less predictable.

In the current situation, poor governance exists in a number of places worldwide. This is the situation in much of the developing world, such as the Middle East, Africa, South America, and parts of Asia.

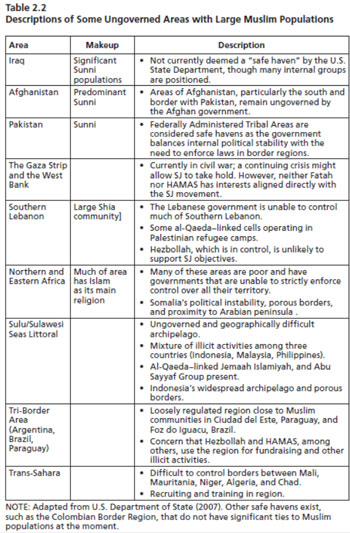

In the current context of the long war, and the particular ideology that is being fought against, only some areas are important, and so only these areas will be considered in relation to poor governance. These correspond to areas where SJ groups might establish safe havens. To meet this requirement, there would seem to be a minimum level of support from local Muslims. This requirement essentially sets the “theater of operation” on some level, but has implications for future spillover into less religiously connected areas.

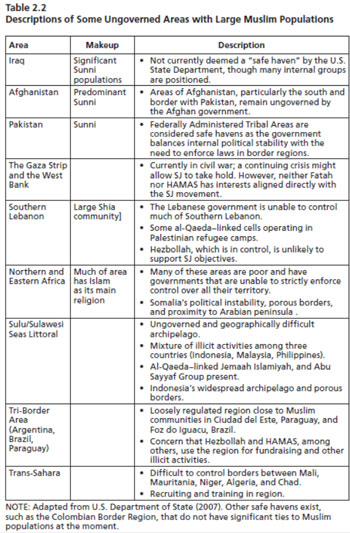

Given the position of the United States as the world’s only superpower, and an aggressive prosecution of this long war, particularly in the destruction of the Taliban regime in Afghanistan as a demonstration of the perils of collaborating with SJ, it seems unlikely that any government with the ability to prevent the use of its territory by SJ would allow it. There are still areas of interest where the local government would not have the ability to stop SJ if they were to try to establish a safe base. (Additional discussion on state sponsorship is found in Chapter Four under the “Uncertainties” subsection.) Areas designated “ungoverned” are described in Table 2.2.

Terrorism in the Current Long War17Triggering the current emphasis on the long war was the terrorist attack on CONUS that occurred on September 11, 2001. While terrorism was not created on that date, the significance of the attacks caused a new understanding of the term. While many analysts, including those at the RAND Corporation, had been warning for some time that an attack like 9/11 was possible, the size and nature of the 9/11 attacks, as well as the following attacks in Bali, Spain, and London, changed the nature of the counterterrorist effort.

Policymakers recognized that terrorists could not only strike at U.S. interests overseas (such as the embassy bombings in Kenya and Tanzania) but also at targets on CONUS itself, and devastatingly so. This turned the counterterrorism effort into a more aggressive and proactive campaign: within one month of the attacks, the United States was attacking the recognized government of Afghanistan, which was harboring the planners of the attacks. The term “War on Terror” was coined, later evolving into the “long war.”18

Table 2.2: Descriptions of Some Ungoverned Areas with Large Muslim Populations

Area / Makeup / Description

Iraq / Significant Sunni populations / • Not currently deemed a “safe haven” by the U.S. State Department, though many internal groups are positioned.

Afghanistan / Predominant Sunni / • Areas of Afghanistan, particularly the south and border with Pakistan, remain ungoverned by the Afghan government.

Pakistan / Sunni / • Federally Administered Tribal Areas are considered safe havens as the government balances internal political stability with the need to enforce laws in border regions.

The Gaza Strip and the West Bank / -- / • Currently in civil war; a continuing crisis might allow SJ to take hold. However, neither Fatah nor HAMAS has interests aligned directly with the SJ movement.

Southern Lebanon / Large Shia community] / • The Lebanese government is unable to control much of Southern Lebanon.

• Some al-Qaeda–linked cells operating in Palestinian refugee camps.

• Hezbollah, which is in control, is unlikely to support SJ objectives.

Northern and Eastern Africa / Much of area has Islam as its main religion / • Many of these areas are poor and have governments that are unable to strictly enforce control over all their territory.

• Somalia’s political instability, porous borders, and proximity to Arabian peninsula.

Sulu/Sulawesi Seas Littoral / -- / • Ungoverned and geographically difficult archipelago.

• Mixture of illicit activities among three countries (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines).

• Al-Qaeda–linked Jemaah Islamiyah, and Abu Sayyaf Group present.

• Indonesia’s widespread archipelago and porous borders.

Tri-Border Area (Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay) / -- / • Loosely regulated region close to Muslim communities in Ciudad del Este, Paraguay, and Foz do Iguacu, Brazil.

• Concern that Hezbollah and HAMAS, among others, use the region for fundraising and other illicit activities.

Trans-Sahara / -- / Difficult to control borders between Mali, Mauritania, Niger, Algeria, and Chad.

• Recruiting and training in region.

NOTE: Adapted from U.S. Department of State (2007). Other safe havens exist, such as the Colombian Border Region, that do not have significant ties to Muslim populations at the moment.

Terrorists have also increased their capability. This has occurred for several reasons, which are also discussed at length in the literature. Among those reasons are the following:

• increased lethality of individual actions

• increased ability to organize through modern communications

• greater ability to publicize their message for motivation and to recruit.

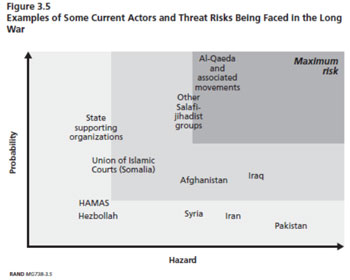

These factors combine to mean that while, as discussed elsewhere in this report, the United States continues to face conventional threats, the relative risk of terrorism in terms of both the risk and hazard remains higher than it did during the Cold War. Further discussion and elucidation of terrorism and its relation to the long war is provided in Appendix A.

Toward Defining the ParticipantsThe question thus remains: Who is the United States facing in this long war? Namely, when considering the current confluence of governance, terrorism, and ideology, who threatens the United States and who else, in addition to those, is involved? The next chapter describes a framework for considering the various nonstate groups implicated in the long war, and one way of envisioning the various other potential actors to be involved in the future long war.

_______________

Notes: (Chapter 2)1 Any quotes taken from the NLWS are not for attribution, and thus names are withheld in this report.

2 Admiral Mullen was recently picked to be Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff and issued guidance to the Joint Staff to “develop a strategy to defend our National interests in the Middle East” (Mullen, 2007, p. 3). Additional objectives highlight the need to “reset, reconstitute, and revitalize our Armed forces” (p. 3) and “properly balance our global strategic risk” (p. 4).

3 Another example of the “long war” that includes confrontation with communism but goes further back in history can be found in Philip Bobbitt’s (2002) articulation of the Peace of Paris, which culminated in parliamentary democracy’s triumph over communism and fascism.

4 John Tirman, “The War on Terror and the Cold War: They’re Not the Same,” MIT Center for International Studies, April 2006. As of July 11, 2007:

http://web.mit.edu/CIS/pdf/Audit_04_06_Tirman.pdf5 Jim Garamone, “Myers Asks Americans to Remain Committed to Terror War,” American Forces Press Service, October 20, 2003. As of July 11, 2007:

http://www.defenselink.mil/news/newsart ... x?id=282916 It should be noted here that the confluence of these three factors—governance, terrorism, and ideology—could be seen across a host of historical struggles, from communist insurgencies to liberation movements, and does not constitute something necessarily unique to the circumstances the United States currently faces.

7 To contrast with the top three approaches, the “civilizational war” definition is deconstructed in a similar way in Appendix B. When the goals and primary adversaries are examined, it can be seen that the civilizational construct is quite different from the GTI war we describe in the remainder of this report. This report does not support the civilizational construct as being a useful explanation for the current problems the United States faces.

8 For a general discussion of ideology, see Appendix C.

9 For a general discussion of the global jihadist movement, see Rabasa et al. (2006).

10 The main founders of this broad-based movement were Muhammad Abduh, Jamal al-Din al-Afghani, and Rashid Rida of Egypt’s al-Azhar University.

11 The Arabic term jihad comes from the Arabic root “to strive” or “to fight.” The exact meaning depends on the context, but Salafi-jihadists tend to use the term to refer to legally sanctioned warfare. Many religious legal precepts guide the proper conduct of jihad, and one of those is takfir. Takfir refers to the process of declaring another individual an “unbeliever.” Under Islamic law, one can attack and kill unbelievers (kafir), justifying the use of jihad. For more information about these terms, see Esposito (2003).

12 Many scholars reject the use of the word “Salafi” to describe these groups, even when coupled with “jihadism,” since the term legitimizes their ideology, which hardly bears resemblance to the spirit of the original movement. These scholars would prefer to use the term “Qutbists” or “Takfiris,” which would have the effect of placing these actors outside the mainstream. A similar comment is made in the CTC publication, Militant Ideology Atlas, (McCants, 2006, p. 5).

13 An overview of concepts of jihad across all Islamic schools of thought is found in Peter (1996).

14 For a general discussion of governance, see Appendix A.

15 Department of Defense (DoD), “Quadrennial Defense Review Report,” Washington, D.C., February 6, 2006, pp. 12, 32. As of July 11, 2007:

http://www.defenselink.mil/qdr16 United Nations Economic and Social Commission of Asia and the Pacific (UNESCAP), “What Is Good Governance?” As of September 2008:

http://www.unescap.org/pdd/prs/ProjectA ... rnance.asp17 For a general discussion of terrorism, see Appendix A.

18 While the damage was significant and the loss of life tremendous, this was not as great as the potential damage from a conventional, let alone a nuclear, confrontation with the USSR during the Cold War. However, the end of the Cold War and the successful attacks on the U.S. homeland elevated the importance of combating terrorism.