The Cambridge Analytica Files‘I made Steve Bannon’s psychological warfare tool’: meet the data war whistleblower

by Carole Cadwalladr

Sun 18 Mar 2018 05.44 EDT First published on Sat 17 Mar 2018 14.00 EDT

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHTYOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ

THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

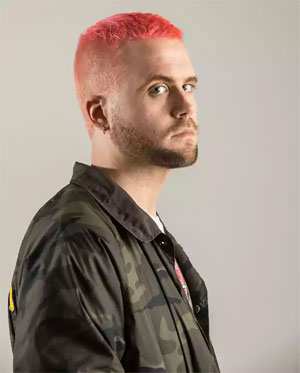

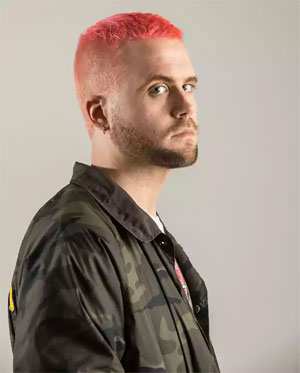

He was the gay Canadian vegan ... diagnosed with ADHD and dyslexia....At six, while at school, Wylie was abused by a mentally unstable person. The school tried to cover it up, blaming his parents, and a long court battle followed. Wylie’s childhood and school career never recovered....His career trajectory has been, like most aspects of his life so far, extraordinary, preposterous, implausible .... He left school at 16 without a single qualification. Yet at 17, he was working in the office of the leader of the Canadian opposition; at 18, he went to learn all things data from Obama’s national director of targeting, which he then introduced to Canada for the Liberal party. At 19, he taught himself to code, and in 2010, age 20, he came to London to study law at the London School of Economics ... Another Lib Dem connection introduced Wylie to a company called SCL Group ....Alexander Nix, then CEO of SCL Elections, made Wylie an offer he couldn’t resist....The job was research director across the SCL group, a private contractor that has both defence and elections operations. Its defence arm was a contractor to the UK’s Ministry of Defence and the US’s Department of Defense ... the British government has paid SCL to conduct counter-extremism operations in the Middle East, and the US Department of Defense has contracted it to work in Afghanistan.... "It’s like dirty MI6 because you’re not constrained"....A few months later, in autumn 2013, Wylie met Steve Bannon ...It was Bannon who took this idea to the Mercers....Nix and Wylie flew to New York to meet the Mercers ...I come to think of his pink hair as a false-flag operation ... Cambridge Analytica is Chris’s Frankenstein. He created it. It’s his data Frankenmonster. And now he’s trying to put it right.

-- The Cambridge Analytica Files, by Carole Cadwalladr

For more than a year we’ve been investigating Cambridge Analytica and its links to the Brexit Leave campaign in the UK and Team Trump in the US presidential election. Now, 28-year-old Christopher Wylie goes on the record to discuss his role in hijacking the profiles of millions of Facebook users in order to target the US electorate

For more than a year we’ve been investigating Cambridge Analytica and its links to the Brexit Leave campaign in the UK and Team Trump in the US presidential election. Now, 28-year-old Christopher Wylie goes on the record to discuss his role in hijacking the profiles of millions of Facebook users in order to target the US electorateThe first time I met Christopher Wylie, he didn’t yet have pink hair. That comes later. As does his mission to rewind time. To put the genie back in the bottle.

By the time I met him in person, I’d already been talking to him on a daily basis for hours at a time. On the phone, he was clever, funny, bitchy, profound, intellectually ravenous, compelling. A master storyteller. A politicker. A data science nerd.

Cambridge Analytica whistleblower: 'We spent $1m harvesting millions of Facebook profiles' – video

Cambridge Analytica whistleblower: 'We spent $1m harvesting millions of Facebook profiles' – videoTwo months later, when he arrived in London from Canada, he was all those things in the flesh. And yet the flesh was impossibly young. He was 27 then (he’s 28 now), a fact that has always seemed glaringly at odds with what he has done. He may have played a pivotal role in the momentous political upheavals of 2016. At the very least, he played a consequential role.

At 24, he came up with an idea that led to the foundation of a company called Cambridge Analytica, a data analytics firm that went on to claim a major role in the Leave campaign for Britain’s EU membership referendum, and later became a key figure in digital operations during Donald Trump’s election campaign.

Or, as Wylie describes it, he was the gay Canadian vegan who somehow ended up creating “Steve Bannon’s psychological warfare mindfuck tool”.

In 2014, Steve Bannon – then executive chairman of the “alt-right” news network Breitbart – was Wylie’s boss. And Robert Mercer, the secretive US hedge-fund billionaire and Republican donor, was Cambridge Analytica’s investor. And the idea they bought into was to bring big data and social media to an established military methodology – “information operations” – then turn it on the US electorate.

It was Wylie who came up with that idea and oversaw its realisation. And it was Wylie who, last spring, became my source.

In May 2017, I wrote an article headlined “The great British Brexit robbery”, which set out a skein of threads that linked Brexit to Trump to Russia. Wylie was one of a handful of individuals who provided the evidence behind it. I found him, via another Cambridge Analytica ex-employee, lying low in Canada: guilty, brooding, indignant, confused. “I haven’t talked about this to anyone,” he said at the time. And then he couldn’t stop talking.By that time, Steve Bannon had become Trump’s chief strategist. Cambridge Analytica’s parent company, SCL, had won contracts with the US State Department and was pitching to the Pentagon, and Wylie was genuinely freaked out. “It’s insane,” he told me one night. “The company has created psychological profiles of 230 million Americans. And now they want to work with the Pentagon? It’s like Nixon on steroids.”

As part of its outreach to U.S. officials,

SCL is touting more than 20 years of experience in shaping voter perceptions and advising militaries and governments around the world on how to conduct effective psychological operations....

Alexander Nix, a senior SCL executive who has overseen its U.S. expansion, confirmed the recent outreach to federal agencies and acknowledged that the company was stepping up its efforts to secure U.S. government business. He said that the push is an extension of the work the company has done as a

subcontractor on a variety of government projects during the last 14 years — and that SCL would have sought the new work no matter who had won the election.

“We’re clearly seeking to augment our existing client services and products with some of the new technologies we’ve been developing in our other sectors, such as the political field,” he said in a phone interview. “But

this is not a radical shake-up or anything new.”

“I’d like to think that regardless of the outcome of the election, we’d be working in this space,” Nix added and said he has not communicated with Bannon about the company’s work.

“We’ve survived different administrations from left and right of the aisle, with different policy agendas.”...

SCL’s main offering,

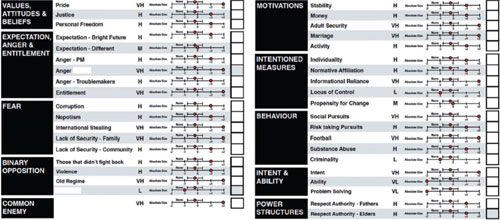

first developed by its affiliated London think tank in 1989, involves gathering vast quantities of data about an audience’s values, attitudes and beliefs, identifying groups of “persuadables” and then targeting them with tailored messages. SCL began testing the technique on health and development campaigns in Britain in the early 1990s, then branched out into international political consulting and later defense contracting....

SCL, which says it has

worked in 100 countries, offers military clients techniques in “soft power.” Nix described it as a modern-day upgrade of early efforts to win over a foreign population by dropping propaganda leaflets from the air.

In a 2015 article for a NATO publication, Steve Tatham, a British military psyops expert who leads SCL’s defense business outside of the United States, explained that one of the benefits of using the company’s techniques is that it “can be undertaken covertly.”

“Audience groups are not necessarily aware that they are the research subjects and government’s role and/or third parties can be invisible,” he wrote.

In the United States, the company’s efforts to win new government contracts are being led by

Josh Weerasinghe, a former vice president of global market development at defense giant BAE Systems who previously worked with Flynn at the Office of the Director of National Intelligence. Flynn served as an adviser to SCL on its efforts to expand its contracting work, according to two people familiar with his role....

“We have been doing this for nearly 30 years,” he said. “I suppose if it didn’t work, we wouldn’t still be in business and we wouldn’t still be growing.”

--

After working for Trump’s campaign, British data firm eyes new U.S. government contracts, by Matea Gold and Frances Stead Sellers

He ended up showing me a tranche of documents that laid out the secret workings behind Cambridge Analytica.

And in the months following publication of my article in May, it was revealed that the company had “reached out” to WikiLeaks to help distribute Hillary Clinton’s stolen emails in 2016. And then we watched as it became a subject of special counsel Robert Mueller’s investigation into possible Russian collusion in the US election.The Observer also received the first of three letters from Cambridge Analytica threatening to sue Guardian News and Media for defamation.

We are still only just starting to understand the maelstrom of forces that came together to create the conditions for what Mueller confirmed last month was “information warfare”. But Wylie offers a unique, worm’s-eye view of the events of 2016. Of how Facebook was hijacked, repurposed to become a theatre of war: how it became a launchpad for what seems to be an extraordinary attack on the US’s democratic process.As early as 2012, the U.S. GAO had concluded that: "the [U.S. StratCom] programs are inadequately tracked, their impact unclear, and the military doesn't know if it is targeting the right foreign audiences." What is needed now is a "divorce" and at last this is happening in the newly established Centre of Excellence (CoE) for Strategic Communications in Riga, Latvia, where the vision and focus are very much on the "audience" and its actual behaviour, not on the synchronisation across varied themes and perceptions. By courtesy of a CAD $1-million donation to the StratCom CoE, the Centre will soon be an accredited training facility using Behavioural Dynamics Institute's

"Target Audience Analysis Methodology" through a Train the Trainer Programme — a purposebuilt NATO course developed and delivered by the Strategic Communications Laboratories Group (SCL) and Information Operations Training and Advisory Services Global (IOTAGlobal) of London, UK.

Verified and validated by government scientific organizations globally, and coincidentally cited as best practice by the U.S. GAO, the TAA programme will be delivered by the UK company SCL, who have spent over $40 million and 25 years, developing this group behaviour prediction tool. In June and July of this year, upwards of 20 students from across the NATO Alliance will begin an eight-week training programme in Riga; Lesson 1, Day 1, Week 1 will explain to the assorted PsyOpers, StratComers and Intelligence Analysts from across the NATO Alliance why attitudes are such poor precursors to behaviours and why trying to make the audience "love us" ("us" may be substituted by ISAF, KFOR, U.S., UK or NATO, etc.) using mass advertising techniques is destined to fail.

AT THE heart of TAA is the ability to empirically diagnose the exact groupings that exist within target populations. Knowing these groupings allows them to be ranked and the ranking depends upon the degree of influence they may have in either promoting or mitigating constructive behaviour. The methodology involves the comprehensive study of a social group of people. It examines this group of people across a host of psycho-social research parameters, and it does so in order to determine how best to change that group's behaviour.

Crucially, it goes much further than opinion polling, which can only examine attitudes. TAA is the decision-maker's tool, which will explain and forecast behaviour — and make scientifically justifiable recommendations to implement programmes to change problematic behaviours. Indeed, it is not simply research for the sake of greater understanding, but TAA achieves many of the crucial tasks that the planners require. Indeed, when undertaken properly, TAA employs innovative and rigorous primary research, drawing together qualitative, quantitative and other methods. This data is then triangulated with extensive expert elicitation and secondary research. It builds up a detailed understanding of current behaviour, values, attitudes, beliefs and norms, and examines everything from whether a group feels in control of its life, to who they respect, and what radio stations they listen to. TAA can be undertaken covertly. Audience groups are not necessarily aware that they are the research subjects and government's role and/or third parties can be invisible. In short, it is a tried, tested and proven methodology.

IF THERE is one lesson that Afghanistan must drum into everyone in the NATO community it is that

understanding the audience is not a "nice to have" but an imperative pre-requisite for success.--

Target Audience Analysis, by Cdr (Rtd.) Dr Steve Tatham Ph.D., Royal Navy, StratCom and TAA Subject Matter Expert

Wylie oversaw what may have been the first critical breach. Aged 24, while studying for a PhD in fashion trend forecasting,

he came up with a plan to harvest the Facebook profiles of millions of people in the US, and to use their private and personal information to create sophisticated psychological and political profiles. And then target them with political ads designed to work on their particular psychological makeup.“We ‘broke’ Facebook,” he says.

And he did it on behalf of his new boss, Steve Bannon.

“Is it fair to say you ‘hacked’ Facebook?” I ask him one night.

He hesitates. “I’ll point out that I assumed it was entirely legal and above board.”

Last month, Facebook’s UK director of policy, Simon Milner, told British MPs on a select committee inquiry into

fake news, chaired by Conservative MP Damian Collins, that Cambridge Analytica did not have Facebook data. The official Hansard extract reads:

Christian Matheson (MP for Chester): “Have you ever passed any user information over to Cambridge Analytica or any of its associated companies?”

Simon Milner: “No.”

Matheson: “But they do hold a large chunk of Facebook’s user data, don’t they?”

Milner: “No. They may have lots of data, but it will not be Facebook user data. It may be data about people who are on Facebook that they have gathered themselves, but it is not data that we have provided.”

Alexander Nix, Cambridge Analytica CEO. Photograph: The Washington Post/Getty Images

Alexander Nix, Cambridge Analytica CEO. Photograph: The Washington Post/Getty ImagesTwo weeks later, on 27 February, as part of the same parliamentary inquiry, Rebecca Pow, MP for Taunton Deane, asked Cambridge Analytica’s CEO, Alexander Nix: “Does any of the data come from Facebook?” Nix replied: “We do not work with Facebook data and we do not have Facebook data.”

And through it all, Wylie and I, plus a handful of editors and a small, international group of academics and researchers, have known that – at least in 2014 – that certainly wasn’t the case, because Wylie has the paper trail. In our first phone call, he told me he had the receipts, invoices, emails, legal letters – records that showed how,

between June and August 2014, the profiles of more than 50 million Facebook users had been harvested. Most damning of all, he had a letter from Facebook’s own lawyers admitting that Cambridge Analytica had acquired the data illegitimately.

Going public involves an enormous amount of risk. Wylie is breaking a non-disclosure agreement and risks being sued. He is breaking the confidence of Steve Bannon and Robert Mercer.

It’s taken a rollercoaster of a year to help get Wylie to a place where it’s possible for him to finally come forward. A year in which Cambridge Analytica has been the subject of investigations on both sides of the Atlantic – Robert Mueller’s in the US, and separate inquiries by the Electoral Commission and the Information Commissioner’s Office in the UK, both triggered in February 2017, after the Observer’s first article in this investigation.

It has been a year, too, in which Wylie has been trying his best to rewind – to undo events that he set in motion. Earlier this month, he submitted a dossier of evidence to the Information Commissioner’s Office and the National Crime Agency’s cybercrime unit. He is now in a position to go on the record: the data nerd who came in from the cold.

There are many points where this story could begin. One is

in 2012, when Wylie was 21 and working for the Liberal Democrats in the UK, then in government as junior coalition partners. His career trajectory has been, like most aspects of his life so far, extraordinary, preposterous, implausible.

Wylie grew up in British Columbia and as a teenager he was diagnosed with ADHD and dyslexia. He left school at 16 without a single qualification. Yet at 17, he was working in the office of the leader of the Canadian opposition; at 18, he went to learn all things data from Obama’s national director of targeting, which he then introduced to Canada for the Liberal party. At 19, he taught himself to code, and in 2010, age 20, he came to London to study law at the London School of Economics.

“Politics is like the mob, though,” he says. “You never really leave. I got a call from the Lib Dems. They wanted to upgrade their databases and voter targeting. So, I combined working for them with studying for my degree.”Politics is also where he feels most comfortable. He hated school, but as an intern in the Canadian parliament he discovered a world where he could talk to adults and they would listen. He was the kid who did the internet stuff and within a year he was working for the leader of the opposition.

It showed these odd patterns. People who liked 'I hate Israel' on Facebook also tended to like KitKats

“He’s one of the brightest people you will ever meet,” a senior politician who’s known Wylie since he was 20 told me. “Sometimes that’s a blessing and sometimes a curse.”

Meanwhile, at Cambridge University’s Psychometrics Centre, two psychologists, Michal Kosinski and David Stillwell, were experimenting with a way of studying personality – by quantifying it.

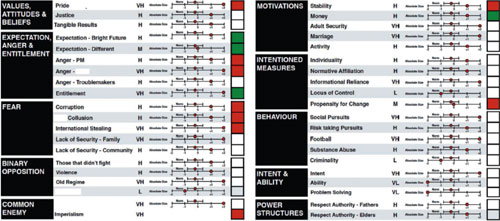

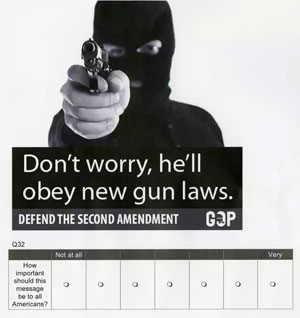

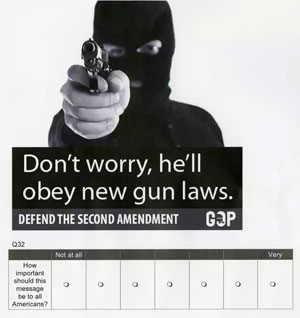

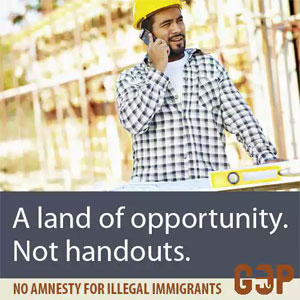

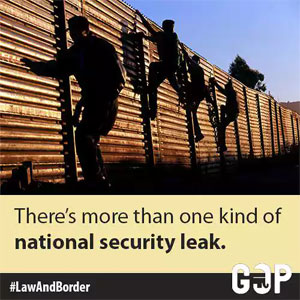

Starting in 2007, Stillwell, while a student, had devised various apps for Facebook, one of which, a personality quiz called myPersonality, had gone viral. Users were scored on “big five” personality traits – Openness, Conscientiousness, Extroversion, Agreeableness and Neuroticism – and in exchange, 40% of them consented to give him access to their Facebook profiles. Suddenly, there was a way of measuring personality traits across the population and correlating scores against Facebook “likes” across millions of people. Examples, above and below, of the visual messages trialled by GSR’s online profiling test. Respondents were asked: How important should this message be to all Americans?

Examples, above and below, of the visual messages trialled by GSR’s online profiling test. Respondents were asked: How important should this message be to all Americans?The research was original, groundbreaking and had obvious possibilities.

“They had a lot of approaches from the security services,” a member of the centre told me. “There was one called You Are What You Like and it was demonstrated to the intelligence services. And it showed these odd patterns; that, for example, people who liked ‘I hate Israel’ on Facebook also tended to like Nike shoes and KitKats.

“There are agencies that fund research on behalf of the intelligence services. And they were all over this research. That one was nicknamed Operation KitKat.”

The defence and military establishment were the first to see the potential of the research. Boeing, a major US defence contractor, funded Kosinski’s PhD and Darpa, the US government’s secretive Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, is cited in at least two academic papers supporting Kosinski’s work.But when, in 2013, the first major paper was published, others saw this potential too, including

Wylie. He had finished his degree and had started his PhD in fashion forecasting, and was thinking about the Lib Dems. It is fair to say that he

didn’t have a clue what he was walking into.

An example of the visual messages trialled by GSR’s online profiling test. Respondents were asked: How important should this message be to all Americans?

An example of the visual messages trialled by GSR’s online profiling test. Respondents were asked: How important should this message be to all Americans?“I wanted to know why the Lib Dems sucked at winning elections when they used to run the country up to the end of the 19th century,” Wylie explains. “And I began looking at consumer and demographic data to see what united Lib Dem voters, because apart from bits of Wales and the Shetlands it’s weird, disparate regions. And what I found is there were no strong correlations. There was no signal in the data.

“And then I came across a paper about how personality traits could be a precursor to political behaviour, and it suddenly made sense.

Liberalism is correlated with high openness and low conscientiousness, and when you think of Lib Dems they’re absent-minded professors and hippies. They’re the early adopters… they’re highly open to new ideas. And it just clicked all of a sudden.”

Here was a way for the party to identify potential new voters. The only problem was that the Lib Dems weren’t interested.

“I did this presentation at which I told them they would lose half their 57 seats, and they were like: ‘Why are you so pessimistic?’ They actually lost all but eight of their seats, FYI.”

Another Lib Dem connection introduced Wylie to a company called SCL Group, one of whose subsidiaries, SCL Elections, would go on to create Cambridge Analytica (an incorporated venture between SCL Elections and Robert Mercer, funded by the latter). For all intents and purposes, SCL/Cambridge Analytica are one and the same.Alexander Nix, then CEO of SCL Elections, made Wylie an offer he couldn’t resist. “He said: ‘We’ll give you total freedom. Experiment. Come and test out all your crazy ideas.’”

An example of the visual messages trialled by GSR’s online profiling test. Respondents were asked: How important should this message be to all Americans?

An example of the visual messages trialled by GSR’s online profiling test. Respondents were asked: How important should this message be to all Americans?In the history of bad ideas, this turned out to be one of the worst. The job was research director across the SCL group, a private contractor that has both defence and elections operations.

Its defence arm was a contractor to the UK’s Ministry of Defence and the US’s Department of Defense, among others. Its expertise was in “psychological operations” – or psyops – changing people’s minds not through persuasion but through “informational dominance”, a set of techniques that includes rumour, disinformation and fake news.

SCL Elections had used a similar suite of tools in more than 200 elections around the world, mostly in undeveloped democracies that Wylie would come to realise were unequipped to defend themselves.

Wylie holds a British Tier 1 Exceptional Talent visa – a UK work visa given to just 200 people a year. He was working inside government (with the Lib Dems) as a political strategist with advanced data science skills. But no one, least of all him, could have predicted what came next. When he turned up at SCL’s offices in Mayfair, he had no clue that he was walking into the middle of a nexus of defence and intelligence projects, private contractors and cutting-edge cyberweaponry.

“The thing I think about all the time is, what if I’d taken a job at Deloitte instead? They offered me one.

I just think if I’d taken literally any other job, Cambridge Analytica wouldn’t exist. You have no idea how much I brood on this.”

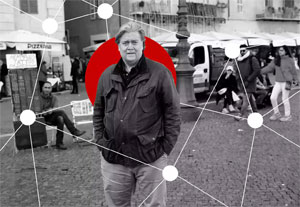

A few months later, in autumn 2013, Wylie met Steve Bannon. At the time, he was editor-in-chief of Breitbart, which he had brought to Britain to support his friend Nigel Farage in his mission to take Britain out of the European Union.What was he like?

“Smart,” says Wylie. “Interesting. Really interested in ideas. He’s the only straight man I’ve ever talked to about intersectional feminist theory. He saw its relevance straightaway to the oppressions that conservative, young white men feel.”

Wylie meeting Bannon was the moment petrol was poured on a flickering flame. Wylie lives for ideas. He speaks 19 to the dozen for hours at a time. He had a theory to prove. And at the time, this was a purely intellectual problem. Politics was like fashion, he told Bannon.

If you do not respect the agency of people, anything you do after that point is not conducive to democracy

-- Christopher Wylie

“[Bannon] got it immediately. He believes in the whole Andrew Breitbart doctrine that politics is downstream from culture, so

to change politics you need to change culture. And fashion trends are a useful proxy for that. Trump is like a pair of Uggs, or Crocs, basically. So how do you get from people thinking ‘Ugh. Totally ugly’ to the moment when everyone is wearing them? That was the inflection point he was looking for.”

But Wylie wasn’t just talking about fashion. He had recently been exposed to a new discipline: “information operations”, which ranks alongside land, sea, air and space in the US military’s doctrine of the “five-dimensional battle space”. His brief ranged across the SCL Group – the British government has paid SCL to conduct counter-extremism operations in the Middle East, and the US Department of Defense has contracted it to work in Afghanistan.I tell him that another former employee described the firm as “MI6 for hire”, and I’d never quite understood it.

“It’s like dirty MI6 because you’re not constrained. There’s no having to go to a judge to apply for permission. It’s normal for a ‘market research company’ to amass data on domestic populations. And if you’re working in some country and there’s an auxiliary benefit to a current client with aligned interests, well that’s just a bonus.”

When I ask how Bannon even found SCL, Wylie tells me what sounds like a tall tale, though it’s one he can back up with an email about how Mark Block, a veteran Republican strategist, happened to sit next to a cyberwarfare expert for the US air force on a plane. “And the cyberwarfare guy is like, ‘Oh, you should meet SCL. They do cyberwarfare for elections.’”

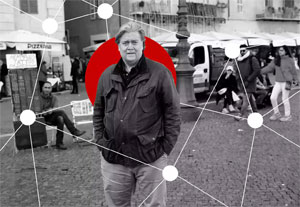

Steve Bannon: ‘He loved the gays,’ says Wylie. ‘He saw us as early adopters.’ Photograph: Tony Gentile/Reuters

Steve Bannon: ‘He loved the gays,’ says Wylie. ‘He saw us as early adopters.’ Photograph: Tony Gentile/ReutersIt was Bannon who took this idea to the Mercers: Robert Mercer – the co-CEO of the hedge fund Renaissance Technologies, who used his billions to pursue a rightwing agenda, donating to Republican causes and supporting Republican candidates – and his daughter Rebekah.

Nix and Wylie flew to New York to meet the Mercers in Rebekah’s Manhattan apartment.“She loved me. She was like, ‘Oh we need more of your type on our side!’”

Your type?

“The gays. She loved the gays. So did Steve [Bannon]. He saw us as early adopters. He figured, if you can get the gays on board, everyone else will follow. It’s why he was so into the whole Milo [Yiannopoulos] thing.”

Robert Mercer was a pioneer in AI and machine translation. He helped invent algorithmic trading – which replaced hedge fund managers with computer programs – and he listened to

Wylie’s pitch. It was for a new kind of political message-targeting based on an influential and groundbreaking 2014 paper researched at Cambridge’s Psychometrics Centre, called: “Computer-based personality judgments are more accurate than those made by humans”.“In politics, the money man is usually the dumbest person in the room. Whereas it’s the opposite way around with Mercer,” says Wylie. “He said very little, but he really listened. He wanted to understand the science. And he wanted proof that it worked.”

And to do that, Wylie needed data.

How Cambridge Analytica acquired the data has been the subject of internal reviews at Cambridge University, of many news articles and much speculation and rumour.

When Nix was interviewed by MPs last month, Damian Collins asked him:

“Does any of your data come from Global Science Research company?”

Nix: “GSR?”

Collins: “Yes.”

Nix: “We had a relationship with GSR. They did some research for us back in 2014. That research proved to be fruitless and so the answer is no.”

Collins: “They have not supplied you with data or information?”

Nix: “No.”

Collins: “Your datasets are not based on information you have received from them?”

Nix: “No.”

Collins: “At all?”

Nix: “At all.”

The problem with Nix’s response to Collins is that Wylie has a copy of an executed

contract, dated 4 June 2014, which confirms that SCL, the parent company of Cambridge Analytica, entered into a commercial arrangement with a company called Global Science Research (GSR), owned by Cambridge-based academic Aleksandr Kogan, specifically premised on the harvesting and processing of Facebook data, so that it could be matched to personality traits and voter rolls.

He has receipts showing that Cambridge Analytica spent $7m to amass this data, about $1m of it with GSR. He has the bank records and wire transfers. Emails reveal Wylie first negotiated with Michal Kosinski, one of the co-authors of the original myPersonality research paper, to use the myPersonality database. But when negotiations broke down, another psychologist, Aleksandr Kogan, offered a solution that many of his colleagues considered unethical. He offered to replicate Kosinski and Stillwell’s research and cut them out of the deal. For Wylie it seemed a perfect solution. “Kosinski was asking for $500,000 for the IP but Kogan said he could replicate it and just harvest his own set of data.” (Kosinski says the fee was to fund further research.)

An unethical solution? Dr Aleksandr Kogan Photograph: alex kogan

An unethical solution? Dr Aleksandr Kogan Photograph: alex koganKogan then set up GSR to do the work, and proposed to Wylie they use the data to set up an interdisciplinary institute working across the social sciences. “What happened to that idea,” I ask Wylie. “It never happened. I don’t know why. That’s one of the things that upsets me the most.”

It was Bannon’s interest in culture as war that ignited Wylie’s intellectual concept. But it was Robert Mercer’s millions that created a firestorm.

Kogan was able to throw money at the hard problem of acquiring personal data: he advertised for people who were willing to be paid to take a personality quiz on Amazon’s Mechanical Turk and Qualtrics. At the end of which Kogan’s app, called thisismydigitallife, gave him permission to access their Facebook profiles. And not just theirs, but their friends’ too. On average, each “seeder” – the people who had taken the personality test, around 320,000 in total – unwittingly gave access to at least 160 other people’s profiles, none of whom would have known or had reason to suspect.

What the email correspondence between Cambridge Analytica employees and Kogan shows is that Kogan had collected millions of profiles in a matter of weeks. But neither Wylie nor anyone else at Cambridge Analytica had checked that it was legal. It certainly wasn’t authorised. Kogan did have permission to pull Facebook data, but for academic purposes only. What’s more, under British data protection laws, it’s illegal for personal data to be sold to a third party without consent.

“Facebook could see it was happening,” says Wylie. “Their security protocols were triggered because Kogan’s apps were pulling this enormous amount of data, but apparently Kogan told them it was for academic use. So they were like, ‘Fine’.”

Kogan maintains that everything he did was legal and he had a “close working relationship” with Facebook, which had granted him permission for his apps.Cambridge Analytica had its data. This was the foundation of everything it did next – how it extracted psychological insights from the “seeders” and then built an algorithm to profile millions more.

For more than a year, the reporting around what Cambridge Analytica did or didn’t do for Trump has revolved around the question of “psychographics”, but Wylie points out: “Everything was built on the back of that data. The models, the algorithm. Everything. Why wouldn’t you use it in your biggest campaign ever?”

In December 2015, the Guardian’s Harry Davies published the first report about Cambridge Analytica acquiring Facebook data and using it to support Ted Cruz in his campaign to be the US Republican candidate. But it wasn’t until many months later that Facebook took action. And then, all they did was write a letter. In August 2016, shortly before the US election, and two years after the breach took place, Facebook’s lawyers wrote to Wylie, who left Cambridge Analytica in 2014, and told him the data had been illicitly obtained and that “GSR was not authorised to share or sell it”. They said it must be deleted immediately. Christopher Wylie: ‘It’s like Nixon on steroids’

Christopher Wylie: ‘It’s like Nixon on steroids’“I already had. But literally all I had to do was tick a box and sign it and send it back, and that was it,” says Wylie.

“Facebook made zero effort to get the data back.”There were multiple copies of it. It had been emailed in unencrypted files.

Cambridge Analytica rejected all allegations the Observer put to them.

Dr Kogan – who later changed his name to Dr Spectre, but has subsequently changed it back to Dr Kogan – is still a faculty member at Cambridge University, a senior research associate. But what his fellow academics didn’t know until Kogan revealed it in emails to the Observer (although Cambridge University says that Kogan told the head of the psychology department), is that he is also an associate professor at St Petersburg University. Further research revealed that he’s received grants from the Russian government to research “Stress, health and psychological well-being in social networks”. The opportunity came about on a trip to the city to visit friends and family, he said.

There are other dramatic documents in Wylie’s stash, including a pitch made by Cambridge Analytica to Lukoil, Russia’s second biggest oil producer. In an email dated 17 July 2014, about the US presidential primaries, Nix wrote to Wylie: “We have been asked to write a memo to Lukoil (the Russian oil and gas company) to explain to them how our services are going to apply to the petroleum business. Nix said that “they understand behavioural microtargeting in the context of elections” but that they were “failing to make the connection between voters and their consumers”. The work, he said, would be “shared with the CEO of the business”, a former Soviet oil minister and associate of Putin, Vagit Alekperov.

“It didn’t make any sense to me,” says Wylie. “I didn’t understand either the email or the pitch presentation we did. Why would a Russian oil company want to target information on American voters?”Mueller’s investigation traces the first stages of the Russian operation to disrupt the 2016 US election back to 2014, when the Russian state made what appears to be its first concerted efforts to harness the power of America’s social media platforms, including Facebook. And it was in late summer of the same year that Cambridge Analytica presented the Russian oil company with an outline of its datasets, capabilities and methodology. The presentation had little to do with “consumers”. Instead, documents show it focused on election disruption techniques. The first slide illustrates how a “rumour campaign” spread fear in the 2007 Nigerian election – in which the company worked – by spreading the idea that the “election would be rigged”. The final slide, branded with Lukoil’s logo and that of SCL Group and SCL Elections, headlines its “deliverables”: “psychographic messaging”.

Robert Mercer with his daughter Rebekah. Photograph: Sean Zanni/Getty Images

Robert Mercer with his daughter Rebekah. Photograph: Sean Zanni/Getty ImagesLukoil is a private company, but its CEO, Alekperov, answers to Putin, and it’s been used as a vehicle of Russian influence in Europe and elsewhere – including in the Czech Republic, where in 2016 it was revealed that an adviser to the strongly pro-Russian Czech president was being paid by the company.

When I asked Bill Browder – an Anglo-American businessman who is leading a global campaign for a Magnitsky Act to enforce sanctions against Russian individuals – what he made of it, he said: “Everyone in Russia is subordinate to Putin. One should be highly suspicious of any Russian company pitching anything outside its normal business activities.”

Last month, Nix told MPs on the parliamentary committee investigating fake news: “We have never worked with a Russian organisation in Russia or any other company. We do not have any relationship with Russia or Russian individuals.”

There’s no evidence that Cambridge Analytica ever did any work for Lukoil. What these documents show, though, is that in 2014 one of Russia’s biggest companies was fully briefed on: Facebook, microtargeting, data, election disruption.Cambridge Analytica is “Chris’s Frankenstein”, says a friend of his. “He created it. It’s his data Frankenmonster. And now he’s trying to put it right.”

Only once has Wylie made the case of pointing out that he was 24 at the time. But he was. He thrilled to the intellectual possibilities of it. He didn’t think of the consequences. And I wonder how much he’s processed his own role or responsibility in it. Instead, he’s determined to go on the record and undo this thing he has created.

Because the past few months have been like watching a tornado gathering force. And when Wylie turns the full force of his attention to something – his strategic brain, his attention to detail, his ability to plan 12 moves ahead – it is sometimes slightly terrifying to behold.

Dealing with someone trained in information warfare has its own particular challenges, and his suite of extraordinary talents include the kind of high-level political skills that makes House of Cards look like The Great British Bake Off. And not everyone’s a fan. Any number of ex-colleagues – even the ones who love him – call him “Machiavellian”. Another described the screaming matches he and Nix would have.

“What do your parents make of your decision to come forward?” I ask him.

“They get it. My dad sent me a cartoon today, which had two characters hanging off a cliff, and the first one’s saying ‘Hang in there.’ And the other is like: ‘Fuck you.’”

Which are you?

“Probably both.”

What isn’t in doubt is what a long, fraught journey it has been to get to this stage. And how fearless he is.

After many months, I learn the terrible, dark backstory that throws some light on his determination, and which he discusses candidly.

At six, while at school, Wylie was abused by a mentally unstable person. The school tried to cover it up, blaming his parents, and a long court battle followed. Wylie’s childhood and school career never recovered. His parents – his father is a doctor and his mother is a psychiatrist – were wonderful, he says. “But they knew the trajectory of people who are put in that situation, so I think it was particularly difficult for them, because they had a deeper understanding of what that does to a person long term.”

Facebook has denied and denied this. It has failed in its duties to respect the law

-- Paul-Olivier Dehaye

He says he grew up listening to psychologists discuss him in the third person, and, aged 14, he successfully sued the British Columbia Ministry of Education and forced it to change its inclusion policies around bullying. What I observe now is how much he loves the law, lawyers, precision, order.

I come to think of his pink hair as a false-flag operation. What he cannot tolerate is bullying.

Is what Cambridge Analytica does akin to bullying?

“I think it’s worse than bullying,” Wylie says. “Because people don’t necessarily know it’s being done to them. At least bullying respects the agency of people because they know. So it’s worse, because

if you do not respect the agency of people, anything that you’re doing after that point is not conducive to a democracy. And fundamentally, information warfare is not conducive to democracy.”Russia, Facebook, Trump, Mercer, Bannon, Brexit. Every one of these threads runs through Cambridge Analytica. Even in the past few weeks, it seems as if the understanding of Facebook’s role has broadened and deepened. The Mueller indictments were part of that, but Paul-Olivier Dehaye – a data expert and academic based in Switzerland, who published some of the first research into Cambridge Analytica’s processes – says it’s become increasingly apparent that Facebook is “abusive by design”.

If there is evidence of collusion between the Trump campaign and Russia, it will be in the platform’s data flows, he says. And Wylie’s revelations only move it on again.

“Facebook has denied and denied and denied this,” Dehaye says when told of the Observer’s new evidence. “It has misled MPs and congressional investigators and it’s failed in its duties to respect the law. It has a legal obligation to inform regulators and individuals about this data breach, and it hasn’t. It’s failed time and time again to be open and transparent.”

Facebook denies that the data transfer was a breach. In addition, a spokesperson said: “Protecting people’s information is at the heart of everything we do, and we require the same from people who operate apps on Facebook. If these reports are true, it’s a serious abuse of our rules. Both Aleksandr Kogan as well as the SCL Group and Cambridge Analytica certified to us that they destroyed the data in question.”

Millions of people’s personal information was stolen and used to target them in ways they wouldn’t have seen, and couldn’t have known about, by a mercenary outfit, Cambridge Analytica, who, Wylie says, “would work for anyone”. Who would pitch to Russian oil companies. Would they subvert elections abroad on behalf of foreign governments?

It occurs to me to ask Wylie this one night.

“Yes.”

Nato or non-Nato?

“Either. I mean they’re mercenaries. They’ll work for pretty much anyone who pays.”

It’s an incredible revelation. It also encapsulates all of the problems of outsourcing – at a global scale, with added cyberweapons. And in the middle of it all are the public – our intimate family connections, our “likes”, our crumbs of personal data, all sucked into a swirling black hole that’s expanding and growing and is now owned by a politically motivated billionaire.

The Facebook data is out in the wild. And for all Wylie’s efforts, there’s no turning the clock back.

Tamsin Shaw, a philosophy professor at New York University, and the author of a recent New York Review of Books article on cyberwar and the Silicon Valley economy, told me that she’d pointed to the possibility of private contractors obtaining cyberweapons that had at least been in part funded by US defence.

She calls Wylie’s disclosures “wild” and points out that “the whole Facebook project” has only been allowed to become as vast and powerful as it has because of the US national security establishment.

“It’s a form of very deep but soft power that’s been seen as an asset for the US. Russia has been so explicit about this, paying for the ads in roubles and so on. It’s making this point, isn’t it? That Silicon Valley is a US national security asset that they’ve turned on itself.”

Or, more simply: blowback.

• Revealed: 50m Facebook profiles harvested in major data breach

• How ‘likes’ became a political weapon

This article was amended on 18 March 2018 to clarify the full title of the British Columbia Ministry of Education