Part 2 of 2

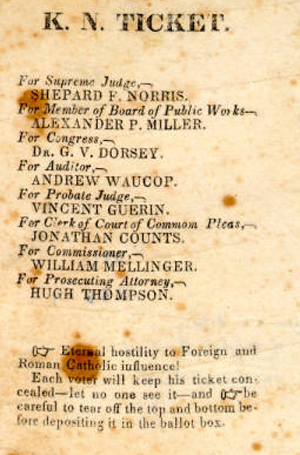

Violence Know Nothing Party ticket naming party candidates for state and county offices (at the bottom of the page are voting instructions)

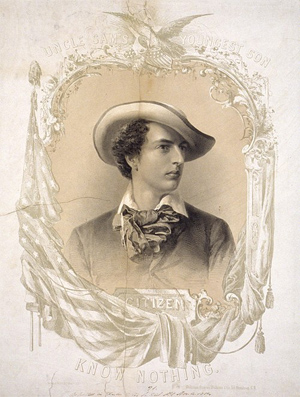

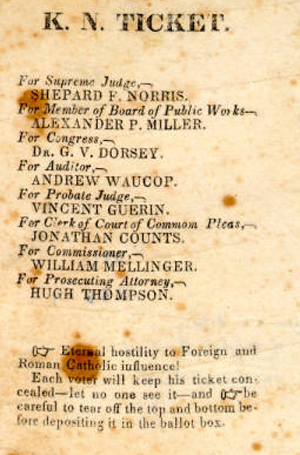

Know Nothing Party ticket naming party candidates for state and county offices (at the bottom of the page are voting instructions)Fearful that Catholics were flooding the polls with non-citizens, local activists threatened to stop them. On 6 August 1855, rioting broke out in Louisville, Kentucky, during a hotly contested race for the office of governor. Twenty-two were killed and many injured. This "Bloody Monday" riot was not the only violent riot between Know Nothings and Catholics in 1855.[39] In Baltimore, the mayoral elections of 1856, 1857, and 1858 were all marred by violence and well-founded accusations of ballot-rigging.[citation needed] In the coastal town of Ellsworth Maine in 1854, Know Nothings were associated with the tarring and feathering of a Catholic priest, Jesuit Johannes Bapst. They also burned down a Catholic church in Bath, Maine.[40]

SouthIn the Southern United States, the American Party was composed chiefly of ex-Whigs looking for a vehicle to fight the dominant Democratic Party and worried about both the pro-slavery extremism of the Democrats and the emergence of the anti-slavery Republican party in the North.[25] In the South as a whole, the American Party was strongest among former Unionist Whigs. States-rightist Whigs shunned it, enabling the Democrats to win most of the South. Whigs supported the American Party because of their desire to defeat the Democrats, their unionist sentiment, their anti-immigrant attitudes and the Know Nothing neutrality on the slavery issue.[41]

David T. Gleeson notes that many Irish Catholics in the South feared the arrival of the Know-Nothing movement portended a serious threat. He argues:

The southern Irish, who had seen the dangers of Protestant bigotry in Ireland, had the distinct feeling that the Know-Nothings were an American manifestation of that phenomenon. Every migrant, no matter how settled or prosperous, also worried that this virulent strain of nativism threatened his or her hard-earned gains in the South and integration into its society. Immigrants fears were unjustified, however, because the national debate over slavery and its expansion, not nativism or anti-Catholicism, was the major reason for Know-Nothing success in the South. The southerners who supported the Know-Nothings did so, for the most part, because they thought the Democrats who favored the expansion of slavery might break up the Union.[42]

In 1855, the American Party challenged the Democrats' dominance. In Alabama, the Know Nothings were a mix of former Whigs, malcontented Democrats and other political misfits; they favored state aid to build more railroads. In the fierce campaign, the Democrats argued that Know Nothings could not protect slavery from Northern abolitionists. The Know Nothing American Party disintegrated soon after losing in 1855.[43]

In Virginia, the Know Nothing movement came under sharp attack from both established parties. Democrats published a 12,000-word, point-by-point denunciation of Know Nothingism. The Democrats nominated ex-Whig Henry A. Wise for governor. He denounced the "lousy, godless, Christless" Know Nothings and instead he advocated an expanded program of internal improvements.[44][45][46]

In Louisiana and Maryland, the Know Nothings enlisted native-born Catholics.[47] In Maryland, the party was dead but its past leaders remained active in other parties. The American Party's Governor and later Senator Thomas Holliday Hicks, Representative Henry Winter Davis, and Senator Anthony Kennedy, with his brother, former Representative John Pendleton Kennedy, all supported the Union in a border state. Historian Michael F. Holt argues that "Know Nothingism originally grew in the South for the same reasons it spread in the North—nativism, anti-Catholicism, and animosity toward unresponsive politicos—not because of conservative Unionism". Holt cites William B. Campbell, former governor of Tennessee, who wrote in January 1855: "I have been astonished at the widespread feeling in favor of their principles—to wit, Native Americanism and anti-Catholicism—it takes everywhere".[48]

LouisianaDespite the national American Party's anti-Catholicism, the Know Nothings found strong support in Louisiana, including in largely Catholic New Orleans.[49] The Whig Party in Louisiana had a strong anti-immigrant bent, making the Native American Party the natural home for Louisiana's former Whigs.[50] Louisiana Know Nothings were pro-slavery and anti-immigrant, but, in contrast to the national party, refused to include a religious test for membership.[51] Instead, the Louisiana Know Nothings insisted that "loyalty to a church should not supersede loyalty to the Union."[50] Know Nothing congressman John Edward Bouligny, a Catholic Creole, was the only member of the Louisiana congressional delegation who refused to resign his seat after the state seceded from the Union.[52]

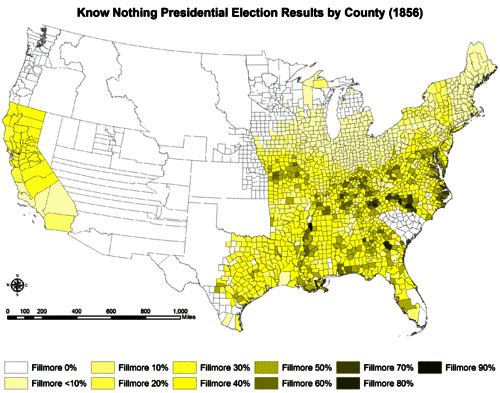

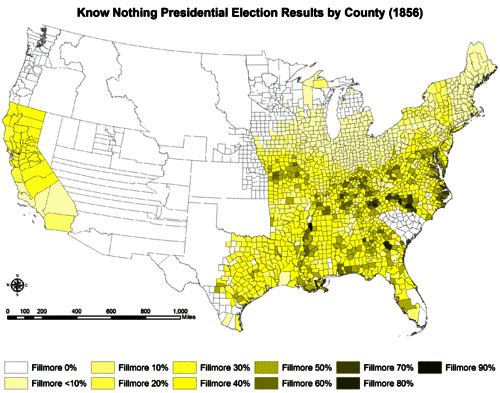

Decline Results by county indicating the percentage for Fillmore in each county

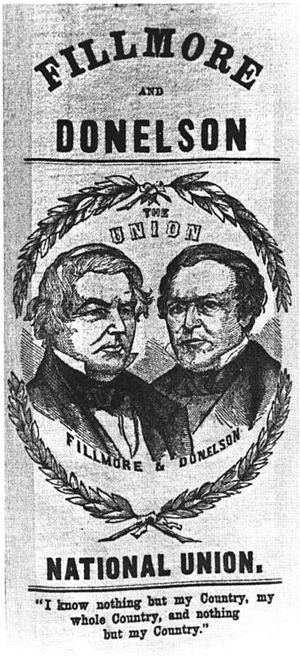

Results by county indicating the percentage for Fillmore in each countyThe party declined rapidly in the North after 1855. In the presidential election of 1856, it was bitterly divided over slavery. The main faction supported the ticket of presidential nominee Millard Fillmore and vice presidential nominee Andrew Jackson Donelson. Fillmore, a former president, had been a Whig and Donelson was the nephew of Democratic President Andrew Jackson, so the ticket was designed to appeal to loyalists from both major parties, winning 23% of the popular vote and carrying one state, Maryland, with eight electoral votes. Fillmore did not win enough votes to block Democrat James Buchanan from the White House. During this time, Nathaniel Banks decided he was not as strongly for the anti-immigrant platform as the party wanted him to be, so he left the Know Nothing Party for the more anti-slavery Republican Party. He contributed to the decline of the Know Nothing Party by taking two-thirds of its members with him.

Many were appalled by the Know Nothings. Abraham Lincoln expressed his own disgust with the political party in a private letter to Joshua Speed, written 24 August 1855. Lincoln never publicly attacked the Know Nothings, whose votes he needed:

I am not a Know-Nothing—that is certain. How could I be? How can any one who abhors the oppression of negroes, be in favor of degrading classes of white people? Our progress in degeneracy appears to me to be pretty rapid. As a nation, we began by declaring that "all men are created equal." We now practically read it "all men are created equal, except negroes." When the Know-Nothings get control, it will read "all men are created equals, except negroes and foreigners and Catholics." When it comes to that I should prefer emigrating to some country where they make no pretense of loving liberty—to Russia, for instance, where despotism can be taken pure, and without the base alloy of hypocrisy.[53]

Historian Allan Nevins, writing about the turmoil preceding the American Civil War, states that Millard Fillmore was never a Know Nothing nor a nativist. Fillmore was out of the country when the presidential nomination came and had not been consulted about running. Nevins further states:

[Fillmore] was not a member of the party; he had never attended an American [Know-Nothing] gathering. By no spoken or written word had he indicated a subscription to American [Party] tenets.[54]

After the Supreme Court's controversial Dred Scott v. Sandford ruling in 1857, most of the anti-slavery members of the American Party joined the Republican Party. The pro-slavery wing of the American Party remained strong on the local and state levels in a few southern states, but by the 1860 election they were no longer a serious national political movement. Most of their remaining members supported the Constitutional Union Party in 1860.[7]

Electoral history

Congressional elections

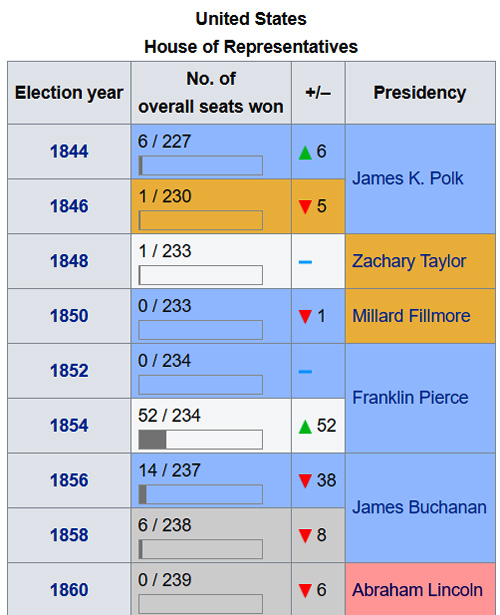

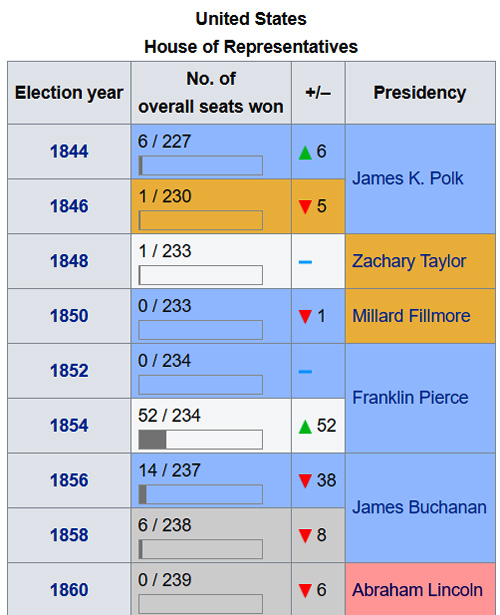

United States House of Representatives

Election year No. of

overall seats won +/– Presidency

1844

6 / 227

Increase 6 James K. Polk

1846

1 / 230

Decrease 5

1848

1 / 233

Steady Zachary Taylor

1850

0 / 233

Decrease 1 Millard Fillmore

1852

0 / 234

Steady Franklin Pierce

1854

52 / 234

Increase 52

1856

14 / 237

Decrease 38 James Buchanan

1858

6 / 238

Decrease 8

1860

0 / 239

Decrease 6 Abraham Lincoln

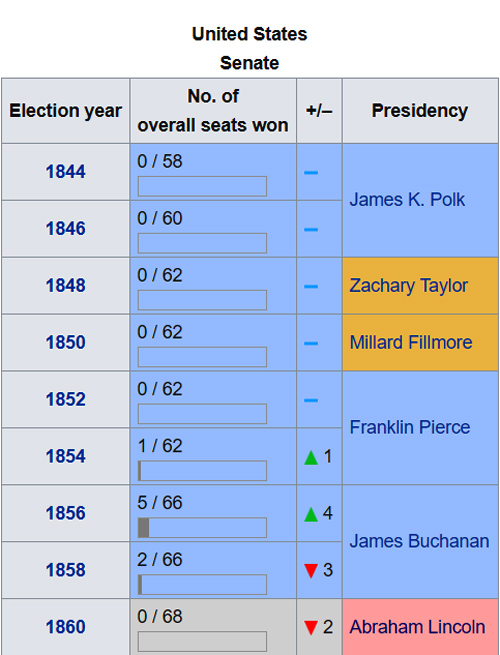

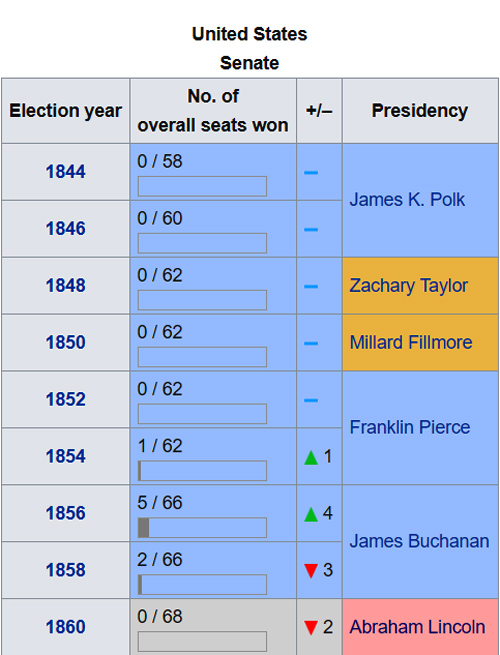

United States Senate

Election year No. of

overall seats won +/– Presidency

1844

0 / 58

Steady James K. Polk

1846

0 / 60

Steady

1848

0 / 62

Steady Zachary Taylor

1850

0 / 62

Steady Millard Fillmore

1852

0 / 62

Steady Franklin Pierce

1854

1 / 62

Increase 1

1856

5 / 66

Increase 4 James Buchanan

1858

2 / 66

Decrease 3

1860

0 / 68

Decrease 2 Abraham Lincoln

Presidential elections

Election Candidate Running mate Votes Vote % Electoral votes +/- Outcome of election

1852 Jacob Broom engraving.jpg

Jacob Broom NPG-S NPG 91 126 29 BCoates Coates-000002 (cropped).jpg

Reynell Coates 2,566 0.1

0 / 294

Steady Democratic victory

1856 Millard Fillmore by Brady Studio 1855-65-crop (3x4 cropp).jpg

Millard Fillmore Andrew J. Donelson portrait.jpg

Andrew Jackson Donelson 873,053 21.5

8 / 294

Increase8 Democratic victory

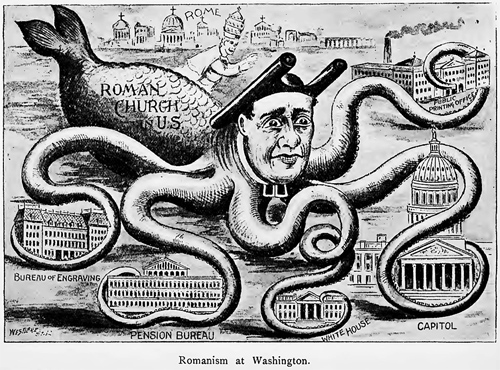

LegacyThe nativist spirit of the Know Nothing movement was revived in later political movements such as the American Protective Association of the 1890s and the Ku Klux Klan of the 1920s.[55] In the late 19th century, Democrats called the Republicans "Know Nothings" in order to secure the votes of Germans as in the Bennett Law campaign in Wisconsin in 1890.[56][57] A similar culture war took place in Illinois in 1892, where Democrat John Peter Altgeld denounced the Republicans:

The spirit which enacted the Alien and Sedition laws, the spirit which actuated the "Know-nothing" party, the spirit which is forever carping about the foreign-born citizen and trying to abridge his privileges, is too deeply seated in the party. The aristocratic and know-nothing principle has been circulating in its system so long that it will require more than one somersault to shake the poison out of its bones.[58]

Some historians and journalists "have found parallels with the Birther and Tea Party movements, seeing the prejudices against Latino immigrants and hostility towards Islam as a similarity".[3] Historians Steve Fraser and Joshue B. Freeman lend their opinion on the Know Nothing and the Tea Party movements, arguing:

Tea Party populism should also be thought of as a kind of identity politics of the right. Almost entirely white, and disproportionately male and older, Tea Party advocates express a visceral anger at the cultural and, to some extent, political eclipse of an America in which people who looked and thought like them were dominant (an echo, in its own way, of the anguish of the Know-Nothings). A black President, female speaker of the house, and a gay head of the House Financial Services Committee are evidently almost too much to bear. Though the anti-immigration and Tea Party movements so far have remained largely distinct (even with growing ties), they share an emotional grammar: the fear of displacement.[3]

Know Nothing has become a provocative slur, suggesting that the opponent is both nativist and ignorant. George Wallace's 1968 presidential campaign was said by Time to be under the "neo-Know Nothing banner". Fareed Zakaria wrote that politicians who "encourage[d] Americans to fear foreigners" were becoming "modern incarnations of the Know-Nothings".[55] In 2006, an editorial in The Weekly Standard by neoconservative William Kristol accused populist Republicans of "turning the GOP into an anti-immigration, Know-Nothing party".[59] The lead editorial of the 20 May 2007 issue of The New York Times on a proposed immigration bill referred to "this generation's Know-Nothings".[60] An editorial written by Timothy Egan in The New York Times on 27 August 2010 and titled "Building a Nation of Know-Nothings" discussed the birther movement, which falsely claimed that Barack Obama was not a natural-born United States citizen, which is a requirement for the office of president of the United States.[61]

In the 2016 United States presidential election, a number of commentators and politicians compared candidate Donald Trump to the Know Nothings due to his anti-immigration policies.[62][63][64][65][66][67]

In popular cultureThe American Party was represented in the 2002 film Gangs of New York, led by William "Bill the Butcher" Cutting (Daniel Day-Lewis), the fictionalized version of real-life Know Nothing leader William Poole. The Know Nothings also play a prominent role in the historical fiction novel Shaman by novelist Noah Gordon.

Notable Know Nothings• Nathaniel P. Banks, Speaker of the United States House of Representatives from Massachusetts and Union Army general

• Levi Boone, mayor of Chicago

• John Wilkes Booth, actor at Ford's Theatre who assassinated President Abraham Lincoln

• John Edward Bouligny, congressman from Louisiana

• Henry Winter Davis, congressman from Maryland

• Andrew Jackson Donelson, Washington D.C. newspaper editor, diplomat to Texas and Prussia, and Andrew Jackson's nephew

• Millard Fillmore, 13th president of the United States

• Thomas Holliday Hicks, governor of Maryland

• William W. Hoppin, governor of Rhode Island[38]

• Sam Houston, senator from Texas[68]

• J. Neely Johnson, governor of California

• Anthony Kennedy, senator from Maryland

• Lewis Charles Levin, politician and social activist

• Samuel Morse, politician, painter and inventor of morse code and the telegraph

• William Poole, politician and a founder and leader of the New York City criminal Nativist gang the Bowery Boys

• Thaddeus Stevens, congressman from Pennsylvania

• Stephen Palfrey Webb, mayor of San Francisco

• Henry Wilson, 18th vice president of the United States

See also• 71st Infantry Regiment (New York)

• John J. Crittenden

• James Greene Hardy

• Samuel Hinks

• Know-Nothing Riot of 1856

• Philadelphia Nativist Riots

• Thomas Swann

• Third Party System

References1. Kierdorf, Douglas (10 January 2016). "Getting to know the Know-Nothings - The Boston Globe". bostonglobe.com. The Boston Globe.

2. Taylor, Stephen (2000). "Progressive Nativism: The Know-Nothing Party in Massachusetts". Historical Journal of Massachusetts. 28 (2): 167–84.

3. "Library Exhibits :: Know Nothings". exhibits.library.villanova.edu. Villanova University.

4. Boissoneault, Lorraine. "How the 19th-Century Know Nothing Party Reshaped American Politics". Smithsonian Magazine. Smithsonian Institute. Retrieved 13 January 2020.

5. Farrell, Robert N. (2017). No Foreign Despots on Southern Soil: The American Party in Alabama and South Carolina, 1850-1857 (MA). University of Southern Mississippi. Retrieved 1 October 2020.

6. Kemp, Bill (17 January 2016). "'Know Nothings' Opposed Immigration in Lincoln's Day". The Pantagraph. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

7. Anbinder, Tyler (1992). Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 270. ISBN 9780195072334. OCLC 925224120.

8. Francis D. Cogliano, No King, No Popery: Anti-Catholicism in Revolutionary New England (Greenwood 1995).

9. Ira M. Leonard, "The Rise and Fall of the American Republican Party in New York City, 1843–1845." New-York Historical Society Quarterly 50 (1966): 151–92.

10. Louis D. Scisco, Political Nativism in New York State (1901) p. 267.

11. Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Know Nothing Party" . Encyclopædia Britannica. 15(11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 877.

12. Levine, Bruce (2001). "Conservatism, Nativism, and Slavery: Thomas R. Whitney and the Origins of the Know-Nothing Party". The Journal of American History. 88 (2): 455–488. doi:10.2307/2675102. JSTOR 2675102.

13. Sean Wilentz. pp. 681–2, 693.

14. Ray A. Billington. pp. 337, 380–406.

15. Ray A. Billington. The Protestant Crusade, 1800–1860 (1938) p. 242.

16. John T. McGreevey. Catholicism and American Freedom: A History (2003) pp. 22–5, 34 (quotation).

17. James M. McPherson, Battle Cry of Freedom, p. 131.

18. Anbinder, Nativism and Slavery, pp. 75–102.

19. Tyler Anbinder. Nativism and Slavery, p. 95.

20. Michael C. LeMay (2012). Transforming America: Perspectives on U.S. Immigration. ABC-CLIO. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-313-39644-1.

21. Richard Lawrence Miller (2012). Lincoln and His World: Volume 4, The Path to the Presidency, 1854–1860. McFarland. pp. 63–4. ISBN 9780786488124.

22. Springfield, Mailing Address: 413 S. 8th Street; Us, IL 62701 Phone:492-4241 Contact. "Lincoln on the Know Nothing Party - Lincoln Home National Historic Site (U.S. National Park Service)".

http://www.nps.gov. Retrieved 17 December 2019.

23. Allan Nevins, Ordeal of the Union: A House Dividing 1852–1857 (1947) 2:396–8.

24. John David Bladek, "'Virginia Is Middle Ground': The Know Nothing Party and the Virginia Gubernatorial Election of 1855". Virginia Magazine of History and Biography(1998): 35–70. JSTOR 4249690.

25. Carey, Anthony Gene (1995). "Too Southern to Be Americans: Proslavery Politics and the Failure of the Know-Nothing Party in Georgia, 1854–1856". Civil War History. 41 (1): 22–40. doi:10.1353/cwh.1995.0023. ISSN 1533-6271.

26. David Harry Bennett, The Party of Fear: From Nativist Movements to the New Right in American History (1988), p. 15.

27. William E. Gienapp. Salmon P. Chase, Nativism, and the Formation of the Republican Party in Ohio, pp. 22, 24. Ohio History, p. 93.

28. John R. Mulkern (1990). The Know-Nothing Party in Massachusetts: The Rise and Fall of a People's Movement. University Press of New England. pp. 74–89. ISBN 9781555530716.

29. Anbinder, Nativism and Slavery, pp. 34–43.

30. Gienapp, William E. (1987). Origins of the Republican Party 1852–1856. pp. 538–542.

31. Formisano, Ronald P. (1983). The Transformation of Political Culture: Massachusetts Parties, 1790s–1840s. p. 332.

32. Taylor, "Progressive Nativism: The Know-Nothing Party in Massachusetts" pp. 171–2.

33. Mulkern (1990). The Know-Nothing Party in Massachusetts: The Rise and Fall of a People's Movement. pp. 101–2. ISBN 9781555530716.

34. Tyler Anbinder, Nativism and Slavery (1992), p. 137

35. John R. Mulkern, "Scandal Behind the Convent Walls: The Know-Nothing Nunnery Committee of 1855." Historical Journal of Massachusetts 11 (1983): 22–34.

36. Oates, Mary J. (1988). "'Lowell': An Account of Convent Life in Lowell, Massachusetts, 1852–1890". New England Quarterly. 61 (1): 101–18. doi:10.2307/365222. JSTOR 365222. reveals the actual behavior of the Catholic nuns.

37. Robert Howard Lord, et al., History of the Archdiocese of Boston in the Various Stages of Development, 1604 to 1943 (1944) pp. 686–99 for more details.

38. McLoughlin, William G. (1986). Rhode Island: A History. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 141–142. ISBN 0-393-30271-7.

39. Charles E. Deusner. "The Know Nothing Riots in Louisville", Register of the Kentucky Historical Society 61 (1963), pp. 122–47.

40. Maine Historical Society, Maine: A History, (1919) Volume 1, lsworth&f=false pp. 304–5 online.

41. Broussard, James H. (1966). "Some Determinants of Know-Nothing Electoral Strength in the South, 1856". Louisiana History: The Journal of the Louisiana Historical Association. 7 (1): 5–20. JSTOR 4230880.

42. David T. Gleeson, The Irish in the South, 1815–1877 (2001) p. 78.

43. Frederick, Jeff (2002). "Unintended Consequences: The Rise and Fall of the Know-Nothing Party in Alabama". Alabama Review. 55 (1): 3–33. Retrieved 23 January2017.[dead link]

44. John David Bladek, "'Virginia Is Middle Ground': The Know Nothing Party and the Virginia Gubernatorial Election of 1855." Virginia Magazine of History and Biography(1998), pp. 35-70 online p. 45.

45. Philip Morrison Rice, "The Know-Nothing Party in Virginia, 1854-1856." Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (1947) 55#1: 61-75, at p. 66 online.

46. Philip Morrison Rice, "The Know-Nothing Party in Virginia, 1854-1856 (Concluded)," Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 55#2 (1947), pp. 159-167 online.

47. Anbinder, Tyler (1992). Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 167. ISBN 978-0-19-507233-4.

48. Holt, Michael F. (1999). The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party: Jacksonian Politics and the Onset of the Civil War. New York, New York: Oxford University Press. p. 856. ISBN 978-0-19-516104-5.

49. Hall, Ryan M. (2015). A Glorious Assemblage: The Rise of the Know-Nothing Party in Louisiana (MA). Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University. Retrieved 4 August 2020.

50. Tarver, Jerry L. (1964). A Rhetorical Analysis of Selected Ante-Bellum Speeches by Randell Hunt (PhD). Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Louisiana State University. Retrieved 20 October 2020.

51. "American Convention". The South-Western. Shreveport, Louisiana. 5 September 1855. p. 1. Retrieved 20 October 2020 – via Newspapers.com. That while we resist all encroachments of spiritual power upon our political rights, we disclaim the calumnious charge of our own opponents that we require a religious test to qualify native born citizens to hold office or enjoy the full rights of citizenship.

52. Bouligny, John Edward (5 February 1861). Feb. 5, 1861: Secession of Louisiana(PDF) (Speech). Speech in the House of Representatives. Washington, D.C. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 February 2017. Retrieved 23 January 2017.

53. Browne, Francis Fisher (1914). The Every-day Life of Abraham Lincoln: A Narrative and Descriptive Biography with Pen-pictures and Personal Recollections by Those Who Knew Him. Browne & Howell. p. 153. Retrieved 28 August 2015.

54. Allan Nevins, Ordeal of the Union: A House Dividing 1852–1857 (1947), 2:467

55. William Safire. Safire's Political Dictionary (2008) pp. 375–76

56. Richard J. Jensen. The Winning of the Midwest: Social and Political Conflict, 1888–96 (1971) pp. 108, 147, 160.

57. Louise Phelps Kellogg. "The Bennett Law in Wisconsin", Wisconsin Magazine of History, Volume 2, #1 (September 1918), p. 13.

58. Jensen. The Winning of the Midwest, p. 220.

59. Craig Shirley. "How the GOP Lost Its Way", The Washington Post, 22 April 2006, p. A21.

60. "The Immigration Deal", The New York Times, 20 May 2007.

61. Egan, Timothy. "Building a Nation of Know-Nothings", The New York Times, 27 August 2010.

62. John Cassidy, "Donald Trump Isn't a Fascist; He's a Media-Savvy Know-Nothing", The New Yorker, 28 December 2015, 16 January 2016.

63. James Nevius "Donald Trump is an immigration Know-Nothing, and dangerous for Republicans", The Guardian, 15 August 2015, 16 January 2016.

64. Helen Raleigh "Is Trump Turning the GOP Into the 'Know Nothing' Party?", Townhall, 19 September 2015, Retrieved on 16 January 2016.

65. Laura Reston "Donald Trump Isn't The First Know Nothing to Capture American Hearts", The New Republic, 30 July 2015, Retrieved on 16 January 2016.

66. Scott Eric Kaufman "Former NY Governor George Pataki: Donald Trump is the 'Know Nothing' candidate of the 21st Century", Salon, 16 December 2015, Retrieved on 16 January 2016.

67. Kiedrowski, Jay (9 September 2016). "Trump: A throwback to the Know-Nothing Party of the 1850s". MinnPost. Retrieved 15 November 2017.

68. Cantrell, Gregg (January 1993). "Sam Houston and the Know-Nothings: A Reappraisal". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 96 (3): 327–343. JSTOR 30237138.

Bibliography• Anbinder, Tyler. Nativism and Slavery: The Northern Know Nothings and the politics of the 1850s (1992). Online version; also online at ACLS History e-Book, the standard scholarly study

• Anbinder, Tyler. "Nativism and prejudice against immigrants," in A companion to American immigration, ed. by Reed Ueda (2006) pp. 177–201 online excerpt

• Baker, Jean H. (1977), Ambivalent Americans: The Know-Nothing Party in Maryland, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins.

• Baum, Dale. "Know-Nothingism and the Republican Majority in Massachusetts: The Political Realignment of the 1850s." Journal of American History 64 (1977–78): 959–86. in JSTOR

• Baum, Dale. The Civil War Party System: The Case of Massachusetts, 1848–1876(1984) online

• Bennett, David Harry. The Party of Fear: From Nativist Movements to the New Right in American History (1988)

• Billington, Ray A. The Protestant Crusade, 1800–1860: A Study of the Origins of American Nativism (1938), standard scholarly survey; online

• Bladek, John David. "'Virginia Is Middle Ground': the Know Nothing Party and the Virginia Gubernatorial Election of 1855." Virginia Magazine of History and Biography 1998 106(1): 35–70. in JSTOR

• Cheathem, Mark R. "'I Shall Persevere in the Cause of Truth': Andrew Jackson Donelson and the Election of 1856". Tennessee Historical Quarterly 2003 62(3): 218–237. ISSN 0040-3261 Donelson was Andrew Jackson's nephew and K–N nominee for Vice President

• Dash, Mark. "New Light on the Dark Lantern: the Initiation Rites and Ceremonies of a Know-Nothing Lodge in Shippensburg, Pennsylvania" Pennsylvania Magazine of History and Biography 2003 127(1): 89–100. ISSN 0031-4587

• Gienapp, William E. "Nativism and the Creation of a Republican Majority in the North before the Civil War," Journal of American History, Vol. 72, No. 3 (Dec., 1985), pp. 529–559 in JSTOR

• Gienapp, William E. The Origins of the Republican Party, 1852–1856 (1978), detailed statistical study, state-by-state

• Gillespie, J. David. Challengers To Duopoly : Why Third Parties Matter in American Two-Party Politics. Columbia, S.C.: University of South Carolina Press, 2012. eBook Collection (EBSCOhost). Web. 4 Dec. 2014.

• Gleeson, David T. The Irish in the South, 1815–1877 Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2001 online

• Holt, Michael F. The Rise and Fall of the American Whig Party (1999) online

• Holt, Michael F. Political Parties and American Political Development: From the Age of Jackson to the Age of Lincoln (1992)

• Holt, Michael F. "The Antimasonic and Know Nothing Parties", in Arthur Schlesinger Jr., ed., History of United States Political Parties (1973), I, 575–620.

• Hurt, Payton. "The Rise and Fall of the 'Know Nothings' in California," California Historical Society Quarterly 9 (March and June 1930).

• Levine, Bruce. "Conservatism, Nativism, and Slavery: Thomas R. Whitney and the Origins of the Know-nothing Party" Journal of American History 2001 88(2): 455–488. in JSTOR

• McGreevey, John T. Catholicism and American Freedom: A History (W. W. Norton, 2003)

• Maizlish, Stephen E. "The Meaning of Nativism and the Crisis of the Union: The Know-Nothing Movement in the Antebellum North." in William Gienapp, ed. Essays on American Antebellum Politics, 1840–1860 (1982) pp. 166–98 online edition

• Melton, Tracy Matthew. Hanging Henry Gambrill: The Violent Career of Baltimore's Plug Uglies, 1854–1860. Baltimore: Maryland Historical Society (2005).

• Mulkern, John R. The Know-Nothing Party in Massachusetts: The Rise and Fall of a People's Movement. Boston: Northeastern UP, 1990. excerpt

• "Nathaniel P. Banks." National Archives and Records Administration. Ed. National Archives. National Archives and Records Administration, n.d. Web. 17 Nov. 2014.

o Nevins, Allan. Ordeal of the Union: A House Dividing, 1852–1857 (1947), overall political survey of era

• Overdyke, W. Darrell. The Know-Nothing Party in the South (1950) online

• Taylor, Steven. "Progressive Nativism: The Know-Nothing Party in Massachusetts" Historical Journal of Massachusetts (2000) 28#2 online

• Voss-Hubbard, Mark. Beyond Party: Cultures of Antipartisanship in Northern Politics before the Civil War (2002)

• Parmet, Robert D. "Connecticut's Know-Nothings: A Profile," Connecticut Historical Society Bulletin (1966), 31 #3, pp. 84–90

• Rice, Philip Morrison. "The Know-Nothing Party in Virginia, 1854–1856." Virginia Magazine of History and Biography (1947): 61–75. in JSTOR

• Scisco, Louis Dow. Political Nativism in New York State (1901) full text online, pp. 84–202

• Wilentz, Sean. The Rise of American Democracy. (2005); ISBN 0-393-05820-4

• ""The First General Order Issued by the Father of His Country after the Declaration of Independence Indicates the Spirit in Which Our Institutions Were Founded and Should Ever Be Defended."" Nathaniel Prentiss (Prentice) Banks. N.p., n.d. Web. 17 Nov. 2014.

Primary sources• Anspach, Frederick Rinehart. The Sons of the Sires: A History of the Rise, Progress, and Destiny of the American Party. Philadelphia: Lippincott, Grambo & Co., 1855. Work by K–N activist.

• Busey, Samuel Clagett (1856). Immigration: Its Evils and Consequences.

• Carroll, Anna Ella (1856). The Great American Battle: Or, The Contest Between Christianity and Political Romanism.

• Fillmore, Millard; Frank H. Severance (ed.)(1907). Millard Fillmore Papers

• One of Them. The Wide-Awake Gift: A Know Nothing Token for 1855. New York: J.C. Derby, 1855.

o Bond, Thomas E. "The 'Know Nothings'", from The Wide-Awake Gift: A Know Nothing Token for 1855. New York: J. C. Derby, 1855; pp. 54–63.

External links• Nativism in the 1856 Presidential Election

• Nativism By Michael F. Holt, PhD

• Lager Beer Riot, Chicago 1855

• "Knownothingism". Catholic Encyclopedia.

• American Party from the Handbook of Texas Online

• Millard Fillmore Was A Know-Nothing

• Texts on Wikisource:

o Know Nothing Platform 1856

o "Know-Nothings". New International Encyclopedia. 1905.