A Decade of Change: Profiles of USAID Assistance to Europe and Eurasia

by USAID

2000

Towards a Market Economy

From the reviewing stand in Moscow’s Red Square, visitors can now gaze across the cobblestones, where Soviet tanks and missiles once rumbled by during the Cold War, and see a new row of privately-owned shops. The once-sleepy downtown of Vilnius, Lithuania, is bustling with commercial activity. In Sofia, Bulgaria, young stockbrokers are making trades on the new stock exchange, where listings went from one company to 31 in its first year.

From Poland and Slovenia in the west, to Kazakhstan and Russian Siberia in the east, the economic changes in Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia during the 1990s were profound and, in some cases, astonishing. In 1989, the state controlled almost every aspect of economic activity—bureaucrats set prices, established production quotas for factories and farms, decided which companies got credit and how much, and determined wages and working conditions.

Governments owned not only utilities and public transportation, but almost every other economic enterprise as well. Private businesses were banned or severely limited. The region was filled with factories employing thousands of workers they didn't need, to produce shoddy goods that no one wanted. For years, the whole system was propped up by subsidies and noncommercial trading relationships and sustained by wasteful use of energy that polluted the land, air and water.

That system crumbled when the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviet Union imploded. Today, the countries of the region are moving—some quickly, and some far too slowly—toward open, market-driven economies. Prices have been freed. State-owned enterprises have been sold to private owners. New economic institutions are leading to improved economic policies and management. A commercial law framework is being put in place and enforced. Sound banking systems and practices are beginning to emerge. Commercial lending to productive private enterprises is growing. Governments are encouraging small and medium enterprises by reducing red tape and improving their tax policies....

‘The land belongs to me’

In the former Soviet Union, agriculture was dominated by huge collective farms, where farmers worked as employees of the state. USAID helped Moldova's government break up these collectives, transforming them into smaller farms owned by the people who once labored on the massive, state-owned farms. Eighty-nine percent of the former collective farms were broken up, and today, 730,000 Moldovan farmers are the proud owners of two million individual land parcels. The success of this program was replicated by USAID in Georgia, where all the collective farms are now gone. USAID followed up by helping to register some one million agricultural land parcels, prompting one Georgian land owner to remark, “From now on the land belongs to me. I have five children and six grandchildren. They work the land, and it will provide for us now.”...

Metering Natural Gas for Conservation

During the Soviet period, the price of natural gas was kept so artificially low that Russians joked it was cheaper to leave a gas stove on all the time than to waste matches lighting it. The result, of course, was that huge amounts of natural gas were wasted. Although the wholesale price of gas rose after 1991, consumers did not conserve, mainly because most Russian apartments do not have individual gas meters. A USAID program that links a U.S. utility and Russian counterpart is helping to change that. Vladmiroblgaz and Brooklyn Union Gas have conducted a pilot residential metering project designed to determine how best to improve revenue collection and conserve energy. With USAID financing, 500 meters were purchased and installed in apartments just east of Moscow. Natural gas consumption dropped dramatically. Since then, the pilot program has been expanded. The Vladmiroblgaz-Brooklyn Union Gas program and others like it are now helping conserve natural resources in cities across Russia....

Helping People In Need

Creating market economies and establishing democracy offer the people of Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia the best long-term hope for higher living standards and a better quality of life. In the short and medium term, however, the weight of change has taken a heavy toll on social services and benefits and caused unemployment and poverty to rise. At the same time, the region has been torn by armed conflicts, causing complex emergencies in the former Yugoslavia and its neighbors, as well as in Armenia, Georgia, Azerbaijan and Tajikistan.

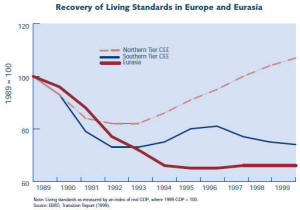

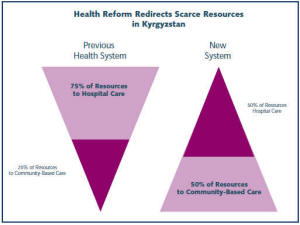

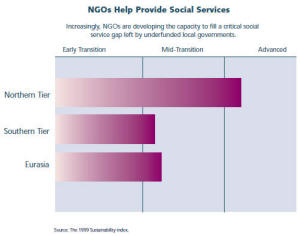

Health, education, and social protection systems—of mediocre quality and largely bankrupt even in 1989—have continued to deteriorate as governments in the region balance competing demands on tight budgetary resources. The transition from a state-controlled system based on broad consumer subsidies to a market economy has resulted in economic and social pain. Inadequate social services and benefits have emerged as serious issues. Only the Northern Tier countries have recovered and exceeded the standards of living in place at the end of the 1980s, although some of their population groups remain vulnerable without some form of help. Many citizens in Southern Tier and Eurasia countries continue to suffer as living standards remain below 1989 levels as a result of incomplete reform....

RESTRUCTURING SOCIAL BENEFITS

A hallmark of the old socialist system was the provision of a basic level of social protection to all its citizens, including universal subsidies for housing, utilities, and social services, and income after retirement, irrespective of need. By 1989, central and local governments could no longer afford to subsidize populations to the same degree as before. During the past decade, USAID has worked with several countries to improve pension system design, financing, and administration and to meet the near-term needs of people through the development of targeted subsidy programs....

Targeted Subsidies in Ukraine

Early in the decade, the Ukrainian Government recognized that it had to take a close look at government spending levels and begin to tackle the issue of universal subsidies. In close coordination with local governments, Ukraine initiated a policy which introduced the recovery of real costs for housing and utilities while also protecting the neediest. Universal subsidies for communal services were replaced with financial assistance targeted to help the poor. USAID provided technical expertise to help the municipalities conduct income surveys and objectively determine cut-off points for government aid. Three months after enactment of the enabling legislation, the national housing subsidy program opened 750 offices across the country. As many families started to pay for housing and related services, those in the low income brackets received subsidies. By 1999, over four million families were being helped with targeted subsidies and the government was realizing a net budget savings of $1.2 billion. The success of this program demonstrated that economic reform could be compatible with social protection and laid the groundwork for other targeted social assistance programs in the region....

The Challenges of the Next Decade

The world is a different place ten years after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Each of the former Soviet bloc countries are now going in their own direction and changing at widely varying paces. The initial exuberance that once led people to dance in the streets of Berlin has been tempered by the reality of change. The path to achieving strong, market-oriented economies and open, democratic societies—where the majority have access to adequate housing, nutrition, health care and education—cannot be traversed quickly or without setbacks.

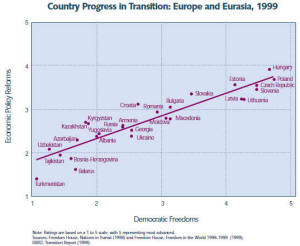

Throughout the 1990s, the many organizations and individuals that worked on USAID’s behalf have shared in the determination of the people of the region to meet the challenges of reform. This hard work has paid off. By the end of 2000, USAID will have closed bilateral assistance missions in eight of the 27 countries, all in the Northern Tier: Czech Republic, Estonia, Hungary, Latvia, Lithuania, Poland, Slovakia, and Slovenia. The wide-ranging reforms implemented by these countries have generated solid economic growth and achieved significant democratic freedoms. Their success sustains the belief that it is possible to achieve lasting reform in this part of the world.

Progress in the rest of the region is mixed. While promising changes have occurred, reform is far from complete. Key economic and political institutions are still being developed and corruption is a widespread problem. Years of ethnic violence have threatened stability and slowed the transition to democracy and private sector growth, particularly in Europe’s Southern Tier. Many of the nations in Eurasia remain tied to the past without sufficient will or momentum to move forward. It will take a lot longer than originally thought for these countries to join the global economy.

A large and stable middle class -- a keystone to enduring democratic systems and dynamic private economies -- still needs to develop. In too many cases, these societies are polarized between a few very wealthy beneficiaries of change and a great number of people who have been unable to access the benefits of reform. At the same time, social services are woefully insufficient, adding to the burden of the common citizen. Toward the end of the decade, one-half of Eurasia’s population and one-quarter of Southern Tier citizens were living in poverty. The turmoil and pain resulting from incomplete reforms have discouraged citizens and led many to long for the certainty of the old Soviet days.

-- A Decade of Change: Profiles of USAID Assistance to Europe and Eurasia, by USAID, 2000

Preface

Donald L. Pressley, Assistant Administrator, USAID, Bureau for Europe and Eurasia

The historic transformation of the countries of the former Soviet bloc into democratic, independent states with market economies is now only 10 years old. For some countries, the process has resulted in great progress and high hopes. For others, the result of this change is less clear. Still, a decade of change is a worthy period to contemplate, so that the next decade will build on the successes and lessons of the first.

In 1989, and again in 1992, the leaders and people of Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia called out to the Western world for help—to make the transition to market-oriented democracies. The United States was at the forefront in responding to that appeal. Many parts of the U.S. government and American populace eagerly joined the effort to show these new independent states how to become market democracies. This publication focuses on the programs and partnerships of the United States Agency for International Development (USAID), the agency that delivers U.S. economic and humanitarian assistance around the world.

Central and Eastern Europe and the republics of the former Soviet Union were a new frontier for USAID in 1989. As a result, USAID had to try new approaches, move quickly, and constantly adjust to changing circumstances. History will tell how USAID ultimately made a difference and whether its role in the sweeping transformation that took place during the last decade had a lasting impact. This presentation looks at these issues after only a decade of change, from the perspective of the people who benefited from USAID programs.

Their stories, and USAID’s story, cannot be captured fully in these few pages. However, we hope that these accounts of real people overcoming tremendous obstacles with the help of USAID will provide readers with a deeper understanding of the progress that has been achieved and the challenges that remain. We want the American people to recognize the economic, political and social issues facing the region. We want American taxpayers to know that, on their behalf, USAID has been active in this part of the world—helping people, providing know-how, supporting change, and, most important, sustaining the hope that, someday, we will all be partners in a shared future of freedom and promise.

Table of Contents

• After the Wall, Facing the Challenge of Change. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 1

• Towards a Market Economy . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

• From Dictatorship to Democracy. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 17

• Helping People in Need . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 29

• The Challenges of the Next Decade. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 39

After the Wall, Facing the Challenge of Change

Gunter Schabowski, the East Berlin Communist leader and Party spokesman . . . pulled his glasses and a document from an inside pocket and began to read: “Private travel . . . can be applied for without the prerequisite travel permission . . . the permit will be issued promptly.”

By now everyone in the room was leaning forward or examining translation devices to be sure they had not been invaded by an alien force. Reporters began to look to each other for affirmation that they were hearing the same words. ‘’Does this include West Berlin?’’ ‘’Yes, yes . . . permanent exit can take place through all border crossings of the G.D.R., to the Federal Republic of Germany or West Berlin.” The wall was open . . . . By midnight, East Germans were pouring through border checkpoints.

—Tom Brokaw, Anchor and Managing Editor of NBC Nightly News

To people who grew up during the Cold War, the events that took place in Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia from 1989 to 1991 still seem hard to believe. In less than two years, the once-powerful Soviet bloc collapsed. The satellite countries of Europe, which had lived under Soviet-backed dictatorships for some 45 years, declared independence. They were followed by the collapse of the 70-year-old Soviet Union itself, which gave rise to yet another diverse group of independent nations, some of which had not ruled themselves for hundreds of years.

The first reaction of the people and around the world was euphoria, symbolized best by the young people who danced in front of the Brandenburg Gate and on top of the Berlin Wall the night of November 9, 1989. And it was no wonder.

For almost half a century, most of the people of Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia had been denied the freedoms the people in the West take for granted. They were isolated from the economies of the West, and their rulers made every effort to cut off ties to Western ideas and culture. The people living in the Soviet Union had been shut off from the West even longer, and government control of almost every aspect of their lives was more complete.

As controls were lifted and isolation ended, however, the euphoria began to change—first to concern, and then to a mixture of hope and fear. A hated authoritarian system was gone, but what would replace it? From one end of the former Soviet bloc to the other, nation after nation faced serious challenges to its economy, capacity to govern, and ability to meet the social needs of its people.

Transition Countries in Europe and Eurasia

The Challenges

Economies in Shambles

Even before the final collapse of the Soviet system, the economies of the region were reeling under the effects of decades of centralized control and mismanagement. Bloated bureaucracies and huge subsidies, which were used to keep the command economies afloat, had driven most of the region close to bankruptcy. The end of Communism pushed country after country over the edge.

The countries of Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia were not prepared to build market economies and compete in the international economic system. For decades, almost all the factories, banks, utilities, natural resources and other productive assets in the region were owned and operated by the state. Private business was either nonexistent or illegal. Few managers, government officials, entrepreneurs or private citizens knew how to organize and operate a free-market economy. And, thanks to years of indifference to the environment, the region’s air, soil and water were severely polluted.

Democratic Futures at Risk

To keep themselves in power, the authoritarian rulers of the region had spent decades stamping out all traces of civil society. There were few functioning democratic institutions or processes, at either the national or local level. Judiciaries were controlled by the government. Parliaments acted as rubber stamps for the Executive. Governments routinely violated civil and human rights. In fact, most people of the region had lived a lifetime without basic democratic freedoms—independent political parties and nongovernmental organizations, free elections, freedom of religion, free speech and the right to challenge government policies. As a result, most of the countries of the region lacked the most basic building blocks needed to create democratic rule. At the same time, the new governments were facing economic and social problems that would have challenged even the most well-established democracies.

A Fraying Social Safety Net

By 1989, health, education and social protection systems in the region were largely bankrupt. They continued to deteriorate during the 1990s as the struggling new governments, strapped for resources, cut spending on social benefits. Unemployment and poverty increased in much of the region, with social services and benefits unable to keep pace. In many countries, life expectancy fell, while infant and child mortality increased. Health problems such as tuberculosis and HIV/AIDS grew rapidly.

Building in ruins at beginning of decade.

“However profound and indelible the changes that have swept their nation and the rest of Eastern Europe, theirs was a disappointment and disillusionment that could be felt to varying degrees from the rusty shipyards of Gdansk in Poland to the frequently darkened streets of Timisoara in Romania. All through the region, newly liberated people face recession, unemployment and insecurity. Obsolete industries crumble on exposure to free markets, energy shortages loom with the shrinking of Soviet supplies and the crisis in the Persian Gulf, and Western investments are slow in coming.”

—New York Times Report, Fall 1990

USAID: Facing the Challenge

Private automobiles were introduced to Albania only in 1991.

The U.S. Stake

As the people of Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia struggled to overcome the legacy of Soviet rule, it quickly became clear that the United States had compelling interests in promoting economic stability and peaceful democratic change. The region’s 27 countries, which cover one-sixth of the globe and are home to 400 million people, could play a critical role in the global economy. The region’s nuclear and other weapons of mass destruction were a major concern. Finally, the United States wanted to respond to the humanitarian needs of the millions of people who became victims of civil conflicts and natural disasters.

A strategy for U.S. assistance to the region crystallized. Helping these countries develop private enterprises and enter global markets would expand opportunities for U.S. trade and investment. Encouraging the development of stable democracies would underline the historic U.S. commitment to democracy and human rights, and promote U.S. national security by decreasing the likelihood of war and diversion of nuclear weapons. Moreover, developing economic and political alliances with the new governments and their people would make it easier to address global challenges such as environmental pollution and the spread of infectious diseases.

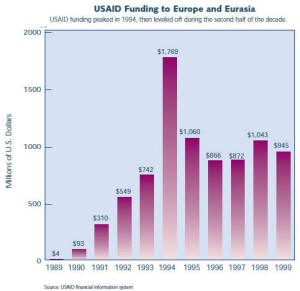

USAID Funding to Europe and Eurasia

USAID funding peaked in 1994, then leveled off during the second half of the decade.

Source: USAID financial information system

A Historic Opportunity, a Dramatic Response

Seizing a historic opportunity to support economic freedom and energize democratic change, the U.S. Congress passed two pieces of legislation to authorize funding for innovative programs: the Support for East European Democracy (SEED) Act in 1989 and the Freedom for Russia and Emerging Eurasian Democracies and Open Markets (FREEDOM) Support Act in 1992.

The U.S. government responded with the most far-reaching agenda for change in Europe since the Marshall Plan. Between 1989 and 1999, the United States funded economic assistance programs to Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia totaling $14 billion. USAID managed 60 percent of this total. Drawing on years of experience, but ready to innovate, USAID moved quickly to assist the region with its historic transformation. USAID initiatives in the economic, democracy, and social sectors complemented one another and promoted national policy change while strengthening local grassroots organizations and businesses. The overarching goal was to create lasting change so that the countries of the region could move beyond U.S. assistance, stand on their own, and become partners in the international arena.

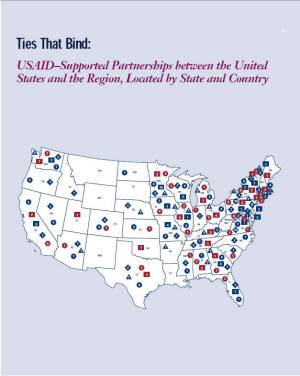

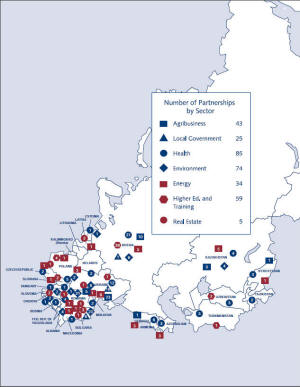

Linkages for Change

USAID has engaged many U.S. grantees and contractors, as well as other U.S. government agencies, to implement programs in the region. USAID has helped nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) across the United States link with counterparts in Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia to establish the broad range of grassroots organizations that are the basic building blocks of democracy. USAID cooperated closely with other parts of the U.S. government, including the Departments of State, Commerce, Energy, Agriculture, Treasury, Labor and Justice; the Export-Import Bank; the Overseas Private Investment Corporation and the Environmental Protection Agency. In addition, USAID has collaborated with international donors and multilateral institutions, such as the European Commission, the World Bank, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development and the International Monetary Fund, as well as public and private donors from Europe and Japan. These wide-ranging relationships have helped leverage additional assistance funds. In 1997, U.S. assistance made up roughly 13 percent of total donor aid to the region.

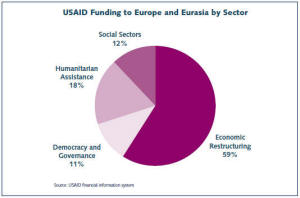

USAID Funding to Europe and Eurasia by Sector

Source: USAID financial information system

Telling USAID's Story

This brief publication cannot describe the thousands of activities USAID supported over the last decade. Instead, the pages that follow tell the human stories of USAID’s impact. The individuals and organizations vary, but the themes are similar: USAID programs have been a potent catalyst for change, helping dedicated men and women contribute to a historic transformation.

While these pages show that a great deal remains to be done, almost every country moved forward in some areas during the 1990s. And important lessons were learned throughout the region. With those lessons firmly in mind, USAID will continue to adapt its support for the nations of Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia as they progress toward freedom and economic prosperity.

“The interesting thing about USAID assistance to the Ministry of Industry and Trade is that the experts didn’t just walk in and start giving advice. We created close working teams. . . . The effect was synergistic and very productive.”

—Jaroslav Borak, Former Director, Ministry of Industry and Trade, the Czech Republic

Towards a Market Economy

From the reviewing stand in Moscow’s Red Square, visitors can now gaze across the cobblestones, where Soviet tanks and missiles once rumbled by during the Cold War, and see a new row of privately-owned shops. The once-sleepy downtown of Vilnius, Lithuania, is bustling with commercial activity. In Sofia, Bulgaria, young stockbrokers are making trades on the new stock exchange, where listings went from one company to 31 in its first year.

From Poland and Slovenia in the west, to Kazakhstan and Russian Siberia in the east, the economic changes in Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia during the 1990s were profound and, in some cases, astonishing. In 1989, the state controlled almost every aspect of economic activity—bureaucrats set prices, established production quotas for factories and farms, decided which companies got credit and how much, and determined wages and working conditions.

Governments owned not only utilities and public transportation, but almost every other economic enterprise as well. Private businesses were banned or severely limited. The region was filled with factories employing thousands of workers they didn't need, to produce shoddy goods that no one wanted. For years, the whole system was propped up by subsidies and noncommercial trading relationships and sustained by wasteful use of energy that polluted the land, air and water.

That system crumbled when the Berlin Wall fell and the Soviet Union imploded. Today, the countries of the region are moving—some quickly, and some far too slowly—toward open, market-driven economies. Prices have been freed. State-owned enterprises have been sold to private owners. New economic institutions are leading to improved economic policies and management. A commercial law framework is being put in place and enforced. Sound banking systems and practices are beginning to emerge. Commercial lending to productive private enterprises is growing. Governments are encouraging small and medium enterprises by reducing red tape and improving their tax policies.

In the 1990s, USAID supported and accelerated these dramatic changes through the transfer of expertise, best practices and experience. In so doing, USAID built lasting partnerships with the men and women of the region who took the risks and did the hard work needed to transform their countries from old to new economies.

USAID Programs

• Privatization

• Fiscal Policy

• Reform

• Financial

• Sector Reform

• New Enterprises

• Energy & Environment

FOUNDATIONS FOR A NEW SYSTEM

Creating a private sector in a former command economy starts with transferring state-owned enterprises into private hands and encouraging the growth of new businesses. For the private sector to succeed, however, a series of changes are required. Laws must be clearly written and fairly enforced by a competent judiciary. Burdensome regulations must be eliminated and competition fostered. Fiscal systems must be reformed to reduce budget deficits and encourage investment. Private businesses need uniform accounting systems in order to prepare financial statements which shareholders and banks can understand. Citizens must gain confidence in financial institutions to promote savings and productive lending. And, good macroeconomic policies and management practices must be adopted to promote non-inflationary growth. During the 1990s, USAID helped transfer thousands of state-owned businesses, farms and housing into private hands. Voucher programs gave many citizens the opportunity to become shareholders of privatized companies. To encourage private sector expansion, USAID supported new legal frameworks, better-functioning government ministries, new tax codes and budget systems, sound financial institutions and professional associations.

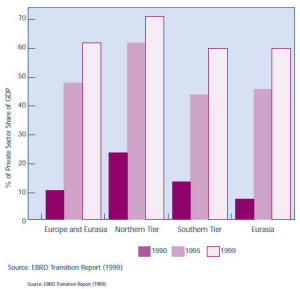

Statistics for the region are impressive. Twenty-three of the 27 countries have either completed the privatization of state-owned enterprises or have privatization programs well under way. Private enterprises in nine countries have adopted international accounting and auditing standards and two regional federations are promoting the acceptance of such standards in member countries. Modern banking systems have been developed in 21 countries. Fiscal reform, has improved tax collection in 13 countries, and seven have cut their budget deficits to below three percent of GDP.

Source: EBRD Transition Report (1999) Source: EBRD Transition Report (1999)

‘The land belongs to me’

In the former Soviet Union, agriculture was dominated by huge collective farms, where farmers worked as employees of the state. USAID helped Moldova's government break up these collectives, transforming them into smaller farms owned by the people who once labored on the massive, state-owned farms. Eighty-nine percent of the former collective farms were broken up, and today, 730,000 Moldovan farmers are the proud owners of two million individual land parcels. The success of this program was replicated by USAID in Georgia, where all the collective farms are now gone. USAID followed up by helping to register some one million agricultural land parcels, prompting one Georgian land owner to remark, “From now on the land belongs to me. I have five children and six grandchildren. They work the land, and it will provide for us now.”

“Only private property can turn ‘agricultural workers’ brought up in a communist spirit into farmers like our ancestors used to be, with their careful attitude toward land, agricultural equipment, and quality work...”

— Nicolae Jechiu, Director Colnarg-Agro Limited Liability Company, Moldova

Best Accountant of the Year

Ms. Valentina Bezhina, who lives in Kazakhstan’s large industrial Karaganda region, works for the Mediton Corp. In 1999, Mediton attempted to convert its accounting systems to new market-oriented standards, but lacked training or technical support. After this conversion attempt failed, Ms. Bezhina took USAID-sponsored training in financial and managerial accounting. Soon after, she began to provide numerous useful ideas that improved Mediton’s financial performance, making her a key part of her company’s decision-making process. She became a consultant to several companies, and she won Kazakhstan’s national competition for Best Accountant of the Year. USAID efforts to reform accounting in Central Asia have not only had a positive impact on economic development, but have improved the quality and dignity of the lives of thousands of people like Valentina Bezhina.

Ms. Bezhina wins national accounting competition in Kazakhstan.

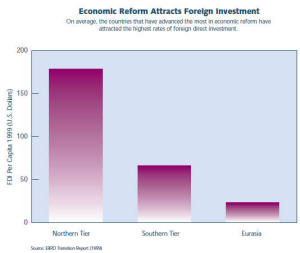

Economic Reform Attracts Foreign Investment

On average, the countries that have advanced the most in economic reform have attracted the highest rates of foreign direct investment.

Source: EBRD Transition Report (1999)

Restoring Confidence in Latvia's Banks

In early 1995, Latvia’s largest bank collapsed, leading to political and economic turmoil and eroding public confidence in the banks and the government. Within days, USAID-funded banking experts provided assistance to design and set up a depositor pay-out system. This allowed for the orderly and timely repayment of over 13,000 household depositors. Over the longer term, these experts helped the Central Bank establish a bank supervision system based on international standards and provided practical assistance to upgrade the on-site inspections of the remaining banks. USAID also helped enact regulations that tightened bank risk management and put in place a complete training process for bank examiners. Numerous risky banks lost their licenses. Bad loans dropped significantly. By 1998, Latvia’s banks were on the right track. Foreign banks were investing in the banking system, a sure sign of progress. Public confidence returned, with deposits by individuals and companies rising 85 percent between 1995 and 1998.

The Northern Tier countries, which introduced the most wide ranging economic reforms, enjoyed a high average annual growth rate of 5 percent between 1996 and 1998.

Stopping a Phony Share Sale

In April 2000, the management of Ukraine’s Stirol Chemicals Plant told the company’s minority shareholders that management wanted to issue new shares worth 10 percent of the company’s stock price to raise new capital to buy plant equipment. But the move was really a ploy to increase management ownership of the company. The new shares were on sale for only 24 hours, on a first-come, first-served basis and could be purchased only on the premises of the chemical plant. Management grabbed all the shares. The minority shareholders turned to Ukraine’s Securities and Stock Market State Commission, a regulatory body set up with USAID assistance. The commission canceled the phony share sale, denounced it as a violation of minority shareholder rights and declared that the law required minority shareholders to have a fair chance to buy into new stock offerings. Shareholder rights were protected thanks to USAID-supported development of new laws and institutions that ensure the proper functioning of securities markets and increase public awareness and investor understanding. Effective protection of shareholder rights is a basic building block of private economic growth.

Security exchange professionals from Eurasia complete regional training seminar on financial market operations, regulation, and oversight. Over 12,000 financial sector professionals have been trained in Eurasia.

HELPING ENTREPRENEURS

The collapse of authoritarian rule left most citizens unprepared to operate in a private, market economy. After so many years of state control, it was hard to find people in the region who knew much about starting a business, managing a banking system, investing in a company, figuring out profit and loss, or any of the other basics of a market-based economy. The countries were short on cash as well as knowledge; almost all needed outside investments to get their economies back on their feet. Throughout the decade, USAID helped people who wanted to become entrepreneurs gain the financing, training, new technologies, expertise and experience they needed to build vibrant growing businesses, the cornerstone of a strong market economy.

Twelve Hundred Loaves a Day

When the Communist system collapsed, Lidiya Tsukrenko’s family almost did too. Ms. Tsukrenko, who lives in the little town of Veprik, Ukraine, about 50 miles south of Kiev, lost her income when the government-owned company she worked for couldn’t make payroll. To earn the cash the family needed, Ms. Tsukrenko got financing from a local source, bought used equipment and started the VITA Bakery in 1995, milling flour in the barn of her small farm and baking bread in her kitchen. She was soon making 300 loaves of bread a day, but realized she had to expand to survive. In 1997, Ms. Tsukrenko applied for a $12,000 loan from a USAID-financed loan company. That loan helped her buy a larger flour mill. Before long, she had more than doubled her production of flour and boosted her bread production to 1,200 loaves per day. The bakery now employs 10 people, and Ms. Tsukrenko has never missed a loan payment.

U.S. volunteers help small entrepreneurs, such as these Eastern European bakers, expand marketability of goods through management and production improvements.

Small herbal tea business in the Russia Far East purchases new equipment with grants available for non-traditional timber products

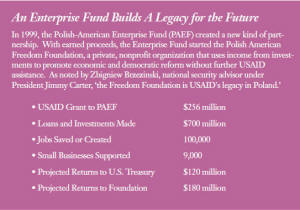

Since 1989, ten Enterprise Funds supported by USAID have invested $900 million in 16 countries, helping to preserve or create 150,000 jobs.

The ‘Dream’ Bank

While Kyrgyzstan’s bazaars look colorful and inviting, they can be a hard place to make a living. In 1996, Ryla Primvirdieva began selling rice in the bazaar of Osh, a small market city. At first, she earned a profit of just $2 per day, barely enough to buy bread and tea for herself and the two young daughters and daughter-in-law she was supporting. Then she heard about the FINCA Village Banking program. Financed through USAID, the program helps women like Ms. Primvirdieva with small loans, as well as training, advice and a savings program.

Ms. Primvirdieva seized the opportunity, and with 11 other women she organized a village bank called Kyigal (‘Dream’). Her first loan allowed her to buy one to two sacks of rice each week, doubling her profits. She qualified for a second FINCA loan of $57, plus $25 borrowed from the bank members’ collective savings. The new financing has allowed her to increase her inventory again, boosting her daily profit to $6. She now has savings, and her additional income allows her to purchase luxuries she could not afford only a few months earlier—butter, sugar and meat.

Sewing Success

As she worked at the state sewing factory in Khabarovsk in the Russian Far East, Olga Asmolina dreamed of owning her own dress shop. When private businesses began to sprout up, she realized she had a golden opportunity. She started by renting a small room with sewing machines. In 1998, Ms. Asmolina decided that she would need a loan to survive and grow. She went to Working Capital Russia, a USAID-sponsored program to help new businesses, and received a $1,000 loan. Soon she had enough business to hire nine employees, including two of the town’s best tailors. When the financial crisis hit Russia in August 1998, Ms. Asmolina had to reschedule her payments, but she managed to pay off the loan by the end of the year. She now has three tailors working for her, has added a fashion salon and fitting room, and has upgraded her equipment and product line. Her dream is a reality.

Support Services Reach Entrepreneurs

USAID has helped small and medium-sized businesses across the region grow and develop. In Bulgaria, for instance, a consortium of USAID-funded organizations has trained more than 10,000 entrepreneurs and created or saved over 14,000 jobs. Nine Business Service Centers in Ukraine and Moldova have reached over 35,000 entrepreneurs. Thirty-five percent of those clients have been women.

Volunteering to Help

When Mitch Kam, a 33-year-old American volunteer with the MBA Enterprise Corps, arrived in Kielce, Poland, in 1994, he knew he had his work cut out for him. Revenues at the Piasecki Company, a 300-person, family-owned construction company, were declining. Mr. Kam stayed a year, advising senior management on marketing, management, strategic planning, finance and organizational design issues. By 2000, Piasecki had grown to more than 800 employees with annual revenues of more than $60 million, making it the seventh-largest general contractor in Poland. Piasecki now is traded on the Warsaw Stock Exchange.

A USAID-supported NGO set up micro-loan institutions that created over 40,000 jobs in the region. More than half the loans have gone to women.

The Dairy Improvement Campaign

In Albania, USAID has worked with Land O’Lakes, Inc., to aid rural women, who are traditionally in charge of the family cows. USAID and Land O’Lakes teamed to create the Dairy Improvement Campaign, which helps women learn how to produce more and better cow's milk. The campaign provided information and training on cow nutrition, disease prevention, reproduction and sanitation. As a result, women are earning more money and enjoying higher status. In addition to the economic and food security impacts of the campaign, other organizations are using the new dairy producers’ network, which has grown to over 8,000 women, to deliver information to women on a wide range of health and social issues.

World Trade Organization (WTO) Membership

Becoming a member of the WTO lowers barriers to trade and provides increased opportunity for economic growth through exports. WTO membership indicates that a country's trade and investment laws encourage foreign investment and promote domestic entrepreneurs. To date, USAID programs have helped 11 countries achieve full membership: Czech Republic, Hungary, Romania, Slovakia, Poland, Slovenia, Bulgaria, Kyrgyzstan, Estonia, Latvia, and Georgia.

Albanian women learn new milk filtering techniques

ENERGY AND ENVIRONMENT

One of the best kept secrets during the Soviet era was the environmental toll of decades of authoritarian rule: rivers and lakes fouled by industrial plant runoff and raw sewage, poisoned soil, polluted air and the threat of exposure to nuclear waste. Much of the damage was caused by the inefficient production and wasteful use of energy, encouraged by the lack of economic value placed on natural resources. Poorly managed energy monopolies as well as artificially low prices set by government contributed to pollution. The damage was compounded by government indifference and suppression of public opinion. The green movements in the countries of Central and Eastern Europe during the 1980s were among the first attempts at citizen participation. USAID built on this momentum and supported new government agencies and private groups working to raise public awareness about the environment, address existing environmental “hot spots,” and reduce the possibility of additional environmental damage. As part of a U.S. Government team, USAID has worked tirelessly to promote nuclear safety in the region. USAID has improved energy efficiency through restructuring, commercialization and privatization of the energy sector and the development of appropriate regulatory oversight for these new market-oriented systems.

Metering Natural Gas for Conservation

During the Soviet period, the price of natural gas was kept so artificially low that Russians joked it was cheaper to leave a gas stove on all the time than to waste matches lighting it. The result, of course, was that huge amounts of natural gas were wasted. Although the wholesale price of gas rose after 1991, consumers did not conserve, mainly because most Russian apartments do not have individual gas meters. A USAID program that links a U.S. utility and Russian counterpart is helping to change that. Vladmiroblgaz and Brooklyn Union Gas have conducted a pilot residential metering project designed to determine how best to improve revenue collection and conserve energy. With USAID financing, 500 meters were purchased and installed in apartments just east of Moscow. Natural gas consumption dropped dramatically. Since then, the pilot program has been expanded. The Vladmiroblgaz-Brooklyn Union Gas program and others like it are now helping conserve natural resources in cities across Russia.

Representatives from Kyivenergo, a local utilities company in Ukraine, discuss safety performance issues with their U.S. partners at the PP&L, Inc. power plant in Allentown, PA.

The New Energy Regulators

Breaking apart old energy monopolies and replacing them with market-oriented systems required a new approach to regulation and oversight in the energy sector. In addressing this challenge, USAID has supported the creation of independent energy regulatory bodies in 14 countries. These new entities operate according to modern and transparent regulatory practices, including increased public participation and less political interference. With help from USAID, the new regulators have developed a regional network to discuss common concerns and link to the U.S. regulatory community.

Improved Environmental Management

Citizen organizations were among the first to call attention to environmental issues in the region. By joining forces with independent media these groups became a strong voice for change. Citizen advocacy combined with USAID technical assistance has helped the development and adoption of new laws and policies in resource management. Sound environmental frameworks are now in place in many countries, including Estonia, Hungary, Poland, Romania, and Slovakia. Groundbreaking forestry codes have been adopted in Russia. The Czech Republic and Poland have produced unprecedented levels of investments in environmental improvements.

New Technologies to Treat Wastewater

A high-tech Hungarian environmental engineering firm plans to float a revolutionary new wastewater treatment plant on the Danube River in 2001, thanks to USAID’s environmental partnership program, EcoLinks. Managed by the Institute of International Education, this program helps businesses and municipalities develop market-based solutions to environmental problems. The Hungarian firm, Organica Ecotechnologies, received the first EcoLinks Quick Response Award of $5,000 and used it to visit an environmental company in Vermont, Ocean Arks International, which had developed a system to use biological technology to treat wastewater.

After the U.S. visit, Organica executives applied for and won a $50,000 challenge grant from EcoLinks to prepare a feasibility study to assess the new technology. A joint venture of international investors heard about the program and decided to invest in Organica. With its new funding, Organica is planning to install its own treatment plant on a 176-foot-long barge. The floating wastewater facility will treat more than 8,800 cubic feet of raw sewage every day.

The introduction of a water filtration and leakage control system in Novokuzretek, Russia, reduced pollution and saved the city money.

Promoting Nuclear Safety

The devastating explosion at the Chernobyl nuclear power plant in Ukraine, in 1986, released high levels of radiation which eventually killed construction workers at the plant. Airborne contamination spread to parts of Europe, Eurasia, and the Middle East, causing considerable damage to soil and vegetation, natural fauna, and livestock. It exposed the local population to elevated levels of radioactivity, resulting in the evacuation of over 100,000 people from the Chernobyl area. Twelve years after the accident, significant health problems continue to emerge, including thyroid cancers and childhood birth defects.

The imperative to avoid another Chernobyl accident has been a vital factor behind the commitment of Western leaders and the international community to address nuclear safety in the region. USAID has worked closely with the U.S. Departments of State and Energy and the National Regulatory Commission to mobilize resources from 30 countries to support safer procedures and structures at operating plants and decommission high-risk nuclear reactors. USAID has collaborated on multilateral efforts, such as the Nuclear Safety Account and the Shelter Implementation Fund at the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development. As a result of this work, commitments have been made by Ukraine, Lithuania, Bulgaria and Slovakia to close their oldest nuclear reactors. Chernobyl is scheduled to shut down by the end of 2000.

From Dictatorship to Democracy

On August 19, 1991, leaders of the Soviet military sent hundreds of tanks rolling through Moscow’s streets, seizing strong points throughout the city and declaring a state of emergency. From the Kremlin, the new Soviet leadership banned protest meetings and closed independent newspapers as it moved to reestablish hard-line control.

The events were all too familiar to people who had lived through the crushing of the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 and the Prague Spring of 1968. But this time, something very different happened. After three days of huge protest rallies and civil disobedience, the people prevailed, pushing the region forward into a decade of historic, political change.

For more than 40 years, dictatorships dominated by the Soviet Union ruled most of the people of Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia. Elections were a sham. Parliaments had no real power. Basic democratic freedoms -- free speech, the freedom to assemble and organize, the right to form independent parties did not exist. Governments trampled human and civil rights. Vaclav Havel, Lech Walesa and other opposition leaders were harassed or imprisoned. Since the fall of the Berlin wall, new political parties have sprung up, wooing voters in elections in 18 countries. Independent television stations and newspapers have allowed dissenting voices to be heard. New nongovernmental organizations have helped citizens press their governments for change. Independent judiciaries have strengthened the rights of private citizens. Local governments have developed new powers and responsibilities. A new generation has been coming to power in many countries in the region. Despite considerable progress, however, moving from dictatorship to democracy has not been easy, especially in nations that have no history or tradition of democratic rule. Setbacks and reversals continue to hinder progress, especially in Eurasia and Europe’s Southern Tier.

Still, the overall political trend in Central and Eastern Europe and Eurasia has been toward increased freedom and democratic practices. U.S. government agencies, working with a wide range of organizations in the region and the United States, as well as with international institutions, have supported these changes and the people who made them. During the past decade, USAID has been in the vanguard, forming lasting linkages with courageous people to sow the seeds of a democratic, civil society.

USAID Programs

• Democratic Elections & Process

• Nongovernmental Organizations

• Independent Media

• Transparent Legal Systems

• Anticorruption Initiatives

• Local Governance

CITIZENS IN ACTION

To survive and succeed, democracy needs civil society—a broad base of active citizens able to influence decisions that affect their lives. Citizens must be able to choose their political leaders at the ballot box, hold their elected governments accountable, and exert pressure on their governments to shape policies that meet the people’s needs and priorities. Democratic societies need vibrant political parties and a free and independent media to engage in public debate of issues and policies. They need strong nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) working for social, economic, and political change. As these citizen groups flourish, they provide vital services to their constituents and become advocates for reform. In a region with little history of democratic practices and institutions, USAID worked with individuals, groups and governments to develop the skills, traditions and institutions that put the people in charge. Since 1989, more than 500,000 NGOs have been created across the region.

“If you want to know why democracy works in some places and not others, de Tocqueville was right . . . it's the strength of civil society.”

— Russ Edgerton, President, American Association for Higher Education

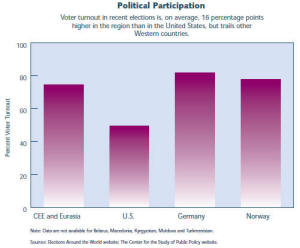

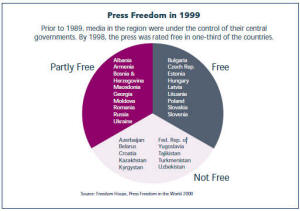

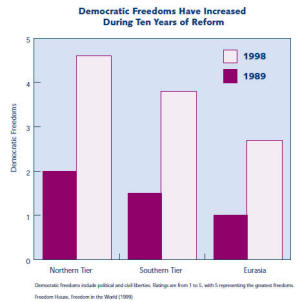

Democratic Freedoms Have Increased During Ten Years of Reform

Democratic freedoms include political and civil liberties. Ratings are from 1 to 5, with 5 representing the greatest freedoms.

Freedom House, Freedom in the World (May 1999)