Measuring Crack Cocaine and Its Impact*

by Roland G. Fryer, Jr. Harvard University Society of Fellows and NBER; Paul S. Heaton University of Chicago; Steven D. Levitt University of Chicago; Kevin M. Murphy University of Chicago

April 2006

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

* We would like to thank Jonathan Caulkins, John Donohue, Lawrence Katz, Glenn Loury, Derek Neal, Bruce Sacerdote, Sudhir Venkatesh, and Ebonya Washington for helpful discussions on this topic. Elizabeth Coston and Rachel Tay provided exceptional research assistance. We gratefully acknowledge the financial support of Sherman Shapiro, the American Bar Foundation, and the National Science Foundation.

Abstract

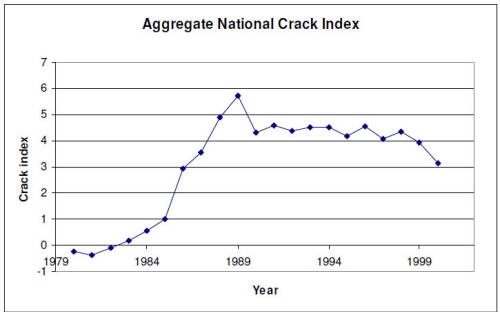

A wide range of social indicators turned sharply negative for Blacks in the late 1980s and began to rebound roughly a decade later. We explore whether the rise and fall of crack cocaine can explain these patterns. Absent a direct measure of crack cocaine’s prevalence, we construct an index based on a range of indirect proxies (cocaine arrests, cocaine-related emergency room visits, cocaine-induced drug deaths, crack mentions in newspapers, and DEA drug busts). The crack index we construct reproduces many of the spatial and temporal patterns described in ethnographic and popular accounts of the crack epidemic. We find that our measure of crack can explain much of the rise in Black youth homicides, as well as more moderate increases in a wide range of adverse birth outcomes for Blacks in the 1980s. Although our crack index remains high through the 1990s, the deleterious social impact of crack fades. One interpretation of this result is that changes over time in behavior, crack markets, and the crack using population mitigated the damaging impacts of crack. Our analysis suggests that the greatest social costs of crack have been associated with the prohibition-related violence, rather than drug use per se.

I. Introduction

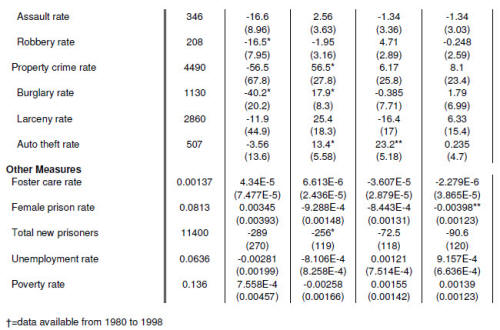

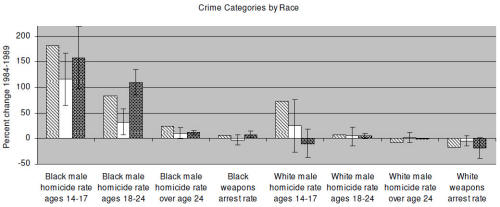

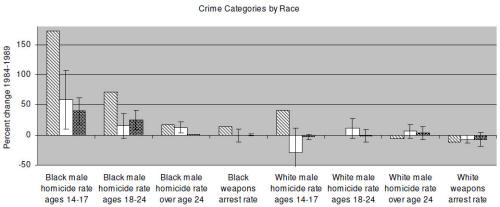

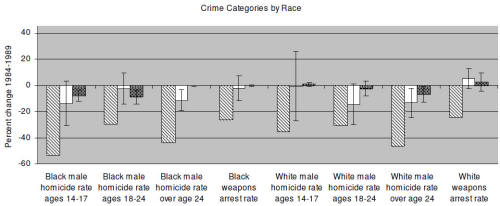

Between 1984 and 1994, the homicide rate for Black males aged 14-17 more than doubled and homicide rates for Black males aged 18-24 increased almost as much, as shown in Figure 1. In stark contrast, homicide rates for Black males 25 and older were essentially flat over the same period. By the year 2000, homicide rates had fallen back below their initial levels of the early 1980s for almost all age groups.1

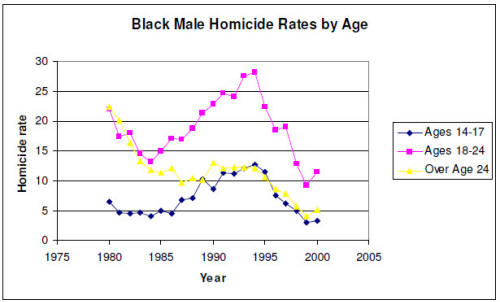

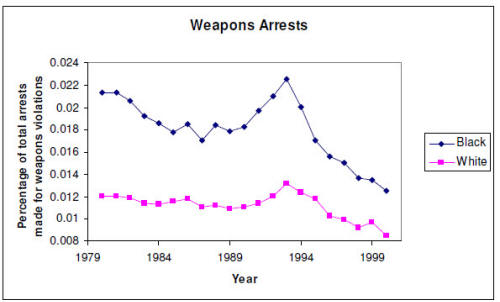

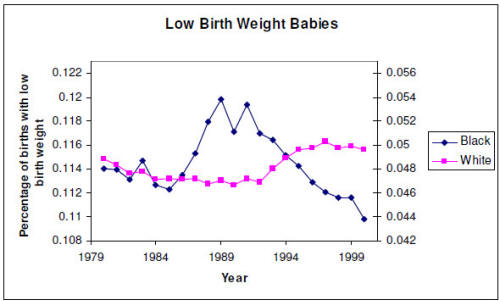

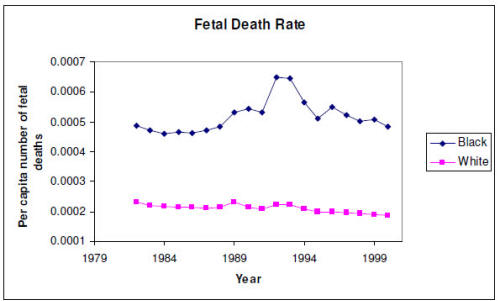

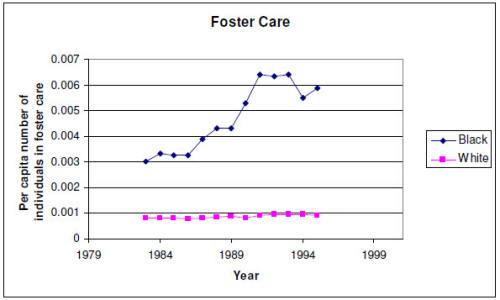

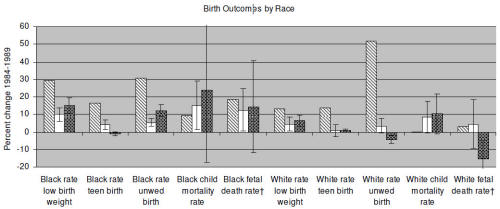

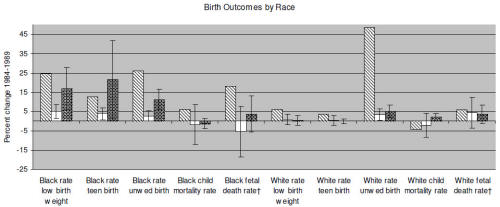

Homicide was not the only outcome that exhibited sharp fluctuations over this time period in the Black community. Figure 2 presents national time series data by race for fetal death rates, low birth weight babies, weapons arrests, and the fraction of children in foster care.2 All of these time series exhibit noticeable increases for Blacks--typically followed by offsetting declines—starting in the late 1980s or early 1990s. The fraction of Black children in foster care more than doubled, fetal death rates and weapons arrests of Blacks rose more than 25 percent, and Black low birth weight babies increased nearly 10 percent.3 Among Whites, there is little evidence of parallel adverse shocks. The poor performance of Blacks relative to Whites represents a break from decades of convergence between Blacks and Whites on many of these measures.4

The concurrent rises and declines in outcomes as disparate as youth homicide, low birth weight babies, and foster care rates presents a puzzle, especially when many standard economic and labor market measures for Blacks show no obvious deviations from trend over the same period (Blank 2001). In this paper, we examine the extent to which one single underlying factor – crack cocaine – can account for the fluctuations in all these outcomes.5

Crack cocaine is a smoked version of cocaine that provides a short, but extremely intense, high. The invention of crack represented a technological innovation that dramatically widened the availability and use of cocaine in inner cities. Virtually unheard of prior to the mid-1980s, crack spread quickly across the country, particularly within Black and Hispanic communities (Bourgois 1996, Chitwood, et al. 1996, Johnson 1991). Many commentators have attributed the spike in Black youth homicide to the crack epidemic’s rise and ebb (Blumstein 1998, Cook and Laub 1998, Cork 1999, and Grogger and Willis 2000). Sold in small quantities in relatively anonymous street markets, crack provided a lucrative market for drug sellers and street gangs (Bourgois 1996, Jacobs 1999). Much of the violence is attributed to attempts to establish property rights not enforceable through legal means (Bourgois 1996, Chitwood, et al. 1996). With respect to other outcomes, the physiological evidence regarding the damage that crack cocaine does to unborn babies suggests that crack usage might explain the patterns in fetal death and low birth weight babies (Frank et. al. 2001, Datta-Bhutatad 1998), although there is no consensus (Zuckerman 2002). The highly addictive nature of crack, combined with relatively high crack usage rates by women (Bourgois 1996, Chitwood, et al. 1996), could contribute to dysfunctional home environments leading to placement of children into foster care.

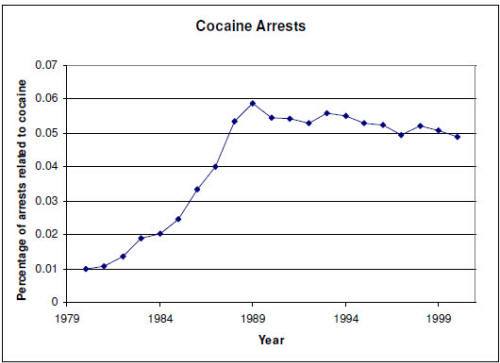

In spite of the general appreciation of the potential role that crack may have played in driving the patterns observed in the data (e.g., Bennett et al. 1996, Wilson 1990), especially with respect to the Black youth homicide spike (Cook and Laub 1998, Blumstein and Rosenfeld 1998, Levitt 2004), there has been remarkably little rigorous empirical analysis of crack’s rise and its corresponding social impact. The scarcity of research appears to be due in part to the great difficulty associated with constructing reliable quantitative measures of the timing and intensity of crack’s presence in local geographic areas. Baumer et al. (1998), Cork (1999), and Ousey and Lee (2004) use cocaine-related arrests as a proxy for crack. Ousey and Lee (2002) supplement arrest data with the fraction of arrestees testing positive for cocaine. Grogger and Willis (2000) use breaks from trend in cocaine-related emergency room visits in a sample of large cities, as well as survey responses from police chiefs in these cities to measure the timing of crack’s arrival. Corman and Mocan (2000) use drug deaths, but the data do not specify which drug is responsible.

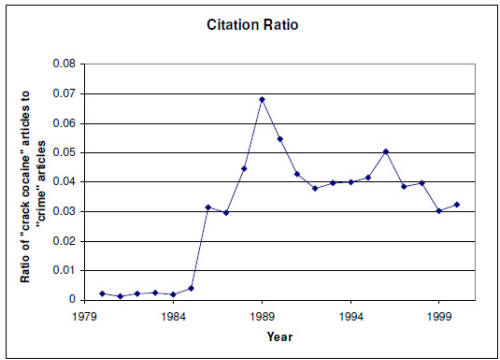

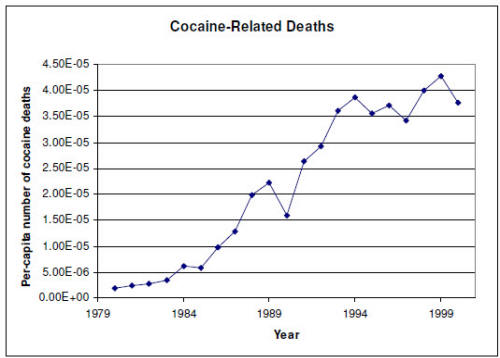

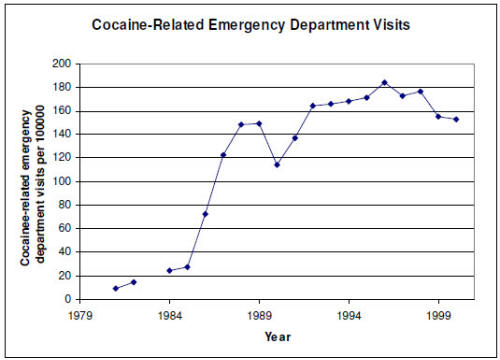

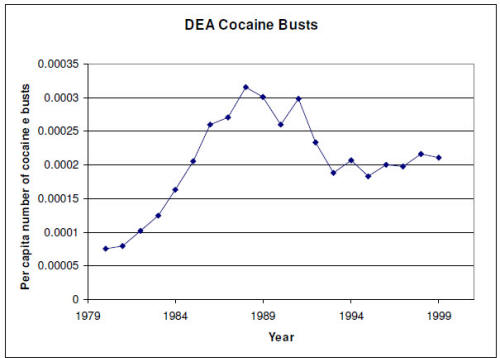

In this paper, we take a somewhat different approach to measuring crack cocaine. Rather than relying on a single measure, we assemble a range of indicators that are likely to proxy for crack. These include cocaine arrests and cocaine-related emergency room visits as in the previous literature, but also the frequency of crack cocaine mentions in newspapers, cocaine-related drug deaths, and the number of DEA drug seizures and undercover drug buys that involve cocaine. While each of these proxies has important shortcomings, together they paint a compelling story for capturing fluctuations in crack. As demonstrated in Figure 3, the national time-series aggregates for these variables tend to follow a similar pattern, rising sharply around 1985, peaking between 1989 and 1993, and in most cases declining thereafter. In spite of the aggregate similarities, using just one of the proxies does not appear to be sufficient for describing crack: the average cross-city correlation in the measures is only about .35. By combining the various measures together into a single factor, however, we are able to generate a crack cocaine index that is not particularly sensitive to any one of the individual measures and corresponds well to the ethnographic and media accounts of crack cocaine’s spread and prevalence. Our measure captures the intensity of crack’s presence in a particular place and time and can be constructed for a wide variety of geographic areas. We estimate our crack index annually for large cities and states over the period 1980-2000. These data available to other researchers.6

We find that crack rose sharply beginning in 1985, peaked in 1989, and slowly declined thereafter. Our estimated crack incidence remains surprisingly high over time – in the year 2000 crack remains at 60-75 percent of its peak level. Crack is concentrated in central cities, particularly those with large Black and Hispanic populations. The cities experiencing the highest average levels of crack are Newark, San Francisco, Philadelphia, Atlanta, and New York. Although crack arrived early to the West Coast, the strongest impacts were ultimately felt in the Northeast and the Middle Atlantic States. The Midwest experienced relatively low rates of crack.

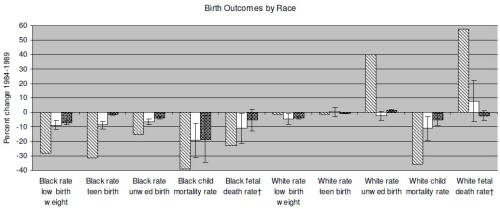

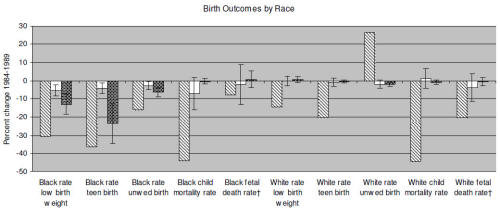

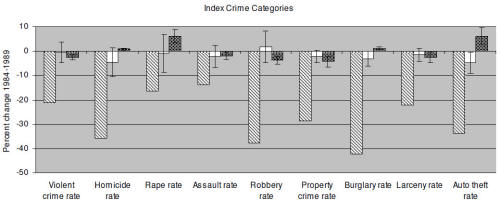

Our index of crack is strongly correlated with a range of social indicators. We find that the rise in crack from 1984-1989 is associated with a doubling of homicide victimizations of Black males aged 14-17, a 30 percent increase for Black males aged 18-24, and a 10 percent increase for Black males 25 and over, and thus accounts for much of the observed variation in homicide rates over this time period.7 The rise in crack can explain 20-100 percent of the observed increases in Black low birth weight babies, fetal death, child mortality, and unwed births in large cities between 1984 and 1989. In contrast, the measured impact of crack on Whites is generally small and statistically insignificant. We estimate that crack is associated with a 5 percent increase in overall violent and property crime in large U.S. cities between 1984 and 1989.8

The link between crack and adverse social outcomes weakens, however, over the course of the sample. Even though crack use does not disappear, the adverse social consequences largely do. Thus, by the year 2000, we observe little impact of crack, which accounts for much of the recovery in homicide rates and child outcomes for Blacks over the period. We hypothesize that the decoupling of crack and violence may be associated with the establishment of property rights and the declining profitability of crack distribution. The fading of adverse child outcomes may be attributable to the concentration of crack usage among a small, aging group of hardcore addicts (MacCoun and Reuter 2001, page 123).

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. Section II provides a brief history of crack cocaine. Section III describes the data we use. Section IV presents our methodology for combining the crack proxies into a single index, presents the results of that exercise, and assesses the determinants of the timing and intensity with which crack hits a city or state. Section V analyzes the extent to which crack can account for the observed fluctuations in social indicators since 1985. Section VI concludes. The appendix outlines the sources of data used and the precise construction of the variables and crack cocaine index.

Section II: A Brief History of Crack Cocaine

Cocaine is a powerful and addictive stimulant first extracted from the coca plant in 1862. During the 19th century, cocaine had a variety of medical uses and could be purchased over the counter, including in the original version of Coca-Cola (Bayer 2000). In the 1970s, inhaled cocaine emerged as a popular but high-priced recreational drug. The street price of pure powder cocaine was roughly $100 to $200 per gram (which is equivalent to $300-$600 per gram in 2004 dollars). The high price of cocaine had two important implications: (1) cocaine use was concentrated among the affluent, and (2) retail cocaine purchases required hundreds of dollars because it was impractical to transact in fractions of grams.9

Crack cocaine is a variation of cocaine made by dissolving powder cocaine in water, adding baking soda, and heating. The cocaine and the baking powder form an airy condensate, that when dried, takes the form of hard, smokeable “rocks.”10 A pebble-sized piece of crack, which contains roughly one-tenth a gram of pure cocaine, sells for $10 on the street and provides an intense high, but one that lasts only fifteen minutes.

Crack is an important technological innovation in many regards. First, crack can be smoked, which is an extremely effective means of delivering the drug psychopharmacologically. Second, because crack is composed primarily of air and baking soda, it is possible to sell in small units containing fractions of a gram of pure cocaine, opening up the market to consumers wishing to spend $10 at a time. Third, because the drug is extremely addictive and the high that comes from taking the drug is so short-lived, crack quickly generated a large following of users wishing to purchase at high rates of frequency. The profits associated with selling crack quickly eclipsed that of other drugs. Furthermore, unlike most other drugs, crack is often sold in open-air, high-volume markets between sellers and buyers who do not know one another.

There are three primary reasons why crack may have been so devastating to the Black community. First, street gangs, which already controlled outdoor spaces, became the logical sellers of crack (Venkatesh and Levitt 2000). Gang violence, primarily as a means of establishing and maintaining property rights, grew dramatically, and potentially accounts for the sharp rise in Black youth violence. Second, the increased returns associated with drug dealing attracted young Black males to gangs and may have reduced educational investment. Third, a large fraction of crack users were young women. Prostitution was common among female crack addicts, potentially accelerating the spread of AIDS and the unwanted birth of low birth weight “crack babies.”11 Crack addicted mothers and fathers are unlikely to provide nurturing home environments for their children (and often ended up incarcerated), leading to the relinquishment of parental rights.

Section III: Data

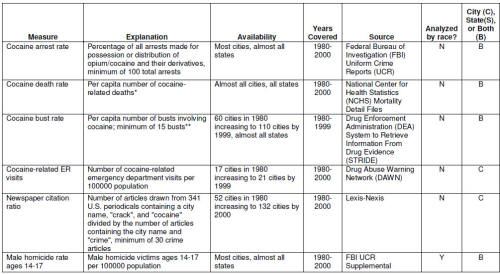

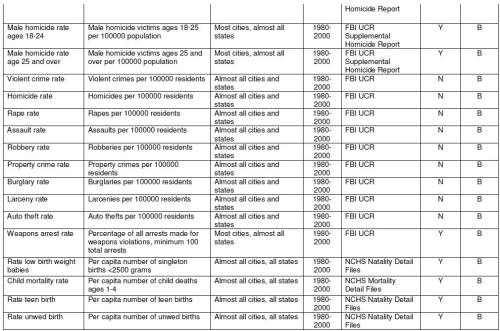

We analyze data separately at the city-level and the state-level. The city-level analysis is carried out on the 144 cities with population greater than 100,000 in 1980. These cities are of particular interest because anecdotal evidence suggests that the problems associated with crack were concentrated in large urban areas. In addition, a number of the variables we use are collected at the city-level, making it a natural unit of analysis. Focusing on the state-level allows us to analyze outcome variables that are not available at the city level, and facilitates a linkage between our work and the large empirical literature carried out using state-level data. In all cases, annual data are used for the period 1980 to 2000.

As noted earlier, we utilize a range of measures to proxy for the prevalence of crack.12 At the city-level, these outcomes are crack-related emergency room visits, cocaine-related arrests, the frequency of crack cocaine mentions in newspapers, DEA drug buys and seizures involving cocaine, and cocaine-related deaths. The emergency room data are based on information from the Drug Abuse Warning Network (DAWN). These data initially covered 14 cities, with that number growing to 19 by the end of the sample. In later years, these data distinguish between crack and powder cocaine, but for consistency over the whole period, we do not exploit this variation.13 The proxy we use is cocaine-related emergency room visits per capita in the metropolitan area. Arrest data are collected by city police departments and are available through the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports. Because of incomplete reporting, we follow Levitt (1998) and define our cocaine arrest measure as cocaine arrests as a fraction of total arrests in the city.14 Our measure of crack cocaine mentions in newspapers is the number of news articles in Lexis-Nexis with a city’s name and the words “crack” and “cocaine,” divided by the total number of articles with the city's name and the word “crime.” By constructing the variable as a ratio, we avoid obvious problems associated with the fact that large cities and those with local newspapers included in Lexis-Nexis will appear much more frequently in the database. The frequency of DEA drug buys and seizures per capita is taken from the System to Retrieve Drug Evidence (STRIDE) data base, which catalogs undercover drug buys and seizures carried out by DEA agents and informants, typically in support of criminal prosecutions. These data include approximately 274,000 cocaine transactions. The city in which the transaction occurred is recorded in the data set. STRIDE does not allow one to definitively distinguish between powder and crack cocaine.15 The final proxy for crack that we use is the rate per capita of cocaine-related deaths, drawn from the annual Mortality Detail File produced by the National Center for Health Statistics. The death data include accidental poisonings, suicides, and deaths due to long-term abuse for which cocaine use was coded by physicians as a primary or contributing factor. We cannot distinguish between crack cocaine and powder cocaine drug deaths in these data.

Each of these proxies suffers from important weaknesses. First, with the exception of the newspaper citations, the measures are unable to clearly differentiate between powder and crack cocaine. Second, both the cocaine arrest and DEA drug buy data are affected not just by the prevalence of crack usage, but also by the intensity of government enforcement efforts (see, for example, Horowitz 2001). Third, the DAWN emergency room data covers only a small set of metropolitan areas and the sample of hospitals that participates changes over time (Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration 2003 Appendix B). Both the emergency room data and the drug death data are potentially affected by the subjective nature of physician determination of the contribution of cocaine to an emergency room visit or a death. Finally, the newspaper citation measure is the output of a relatively crude algorithm and suffers both from the criticism that in the early years of the epidemic there were other terms such as “rock cocaine” that were sometimes used to describe the product before crack cocaine became the agreed upon nomenclature, and also that the newsworthiness of crack-related stories may have declined over time, while consumption continued to rise.

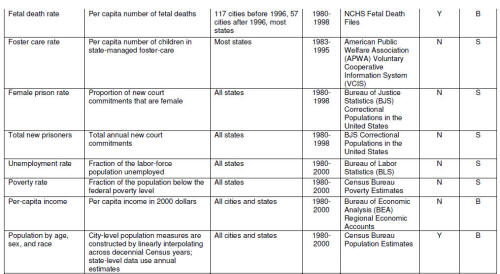

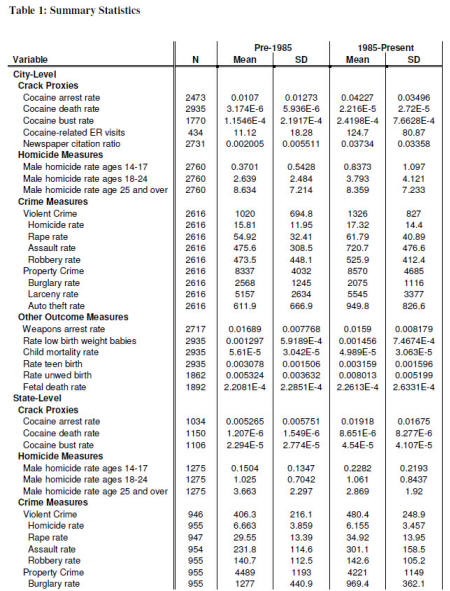

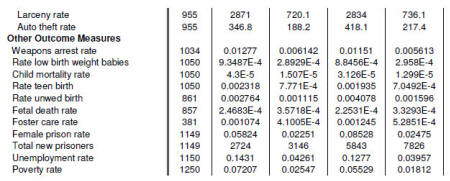

The number of observations, means, and standard deviations for all of these city-level crack proxies are presented in the top panel of Table 1. Values are reported separately for the period prior to and after 1985, the year when crack use is believed to have become widespread. All of these indicators are much higher in the post-1985 period, even for those measures that do not directly distinguish between powder and crack cocaine. Crack mentions in newspapers are extremely low prior to 1985; these instances likely represent false positives in our Lexis-Nexis algorithm.16 Note that the number of observations available varies dramatically across measures due to differences in the cities covered by the data, as well as the years in which data are collected. The data appendix describes the statistical corrections that are done to account for missing values in the construction of our crack index.

When conducting our analysis at the state level, we drop the emergency room and crack citation variables since these measures are available only for a limited number of large cities. The rest of our city-level measures are available at the state-level. The state-level crack proxies are shown in the second panel of Table 1. The absolute levels of the crack proxies are generally lower in states than in large cities, but the patterns are otherwise similar.

The final two panels of Table 1 report the criminal, social, and economic outcomes that we are trying to explain using our crack index at the city-level and state-level respectively. These outcomes include age specific homicide rates, the full set of violent and property crimes tracked in the FBI’s Uniform Crime Reports, fetal death, low-birth weight babies (singleton births only), teen births and unwed births, death rates of children aged one to four, weapons arrests, the number of new admissions to prison, the per capita number of children in the foster care system, the unemployment rate, and the poverty rate. When the data are available we analyze these variables separately by race. Some of the variables are available at the state-level only.

Section III: Identifying Crack

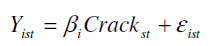

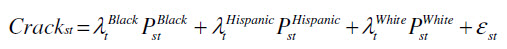

The prevalence of crack cocaine is not directly observable. Instead, we must rely on noisy proxies in an attempt to measure crack. The primary approach that we take for extracting the information available in these proxies is to construct a single index measure of crack using factor analysis.17 In particular, we estimate an equation of the form:

(1)

where the subscripts i, s, and t correspond to particular proxy measures, geographic units, and years respectively. The left-hand-side variables are the proxy measures all of which are stacked into a single vector. The variable Crack is not directly observed, but rather estimated along with the ß's . One could also include covariates on the right-hand side of equation (1) – indeed we allow for city-fixed effects in our baseline estimates – but for simplicity we omit these covariates from the formal discussion.

Estimation of equation (1) generates predicted values both for a set of factors (Crackst) and a set of coefficients (also known as loadings) ßi. We focus our analysis on the single factor that has the greatest explanatory power. Because our proxies are highly correlated, our data are well-described by a one-factor model which captures roughly 50% of the variation in the proxies.18 Additional factors contribute little in terms of explaining the observed variation in our data. The factor with the greatest explanatory power is what we will call “crack,” but more accurately it is the single index that explains the largest share of the variation in our crack proxies. The loadings tell us the degree to which each estimated factor influences the different outcome variables. The crack index we obtain is a weighted average of the proxy variables underlying it, with weights given by the squares of the loadings on each proxy.

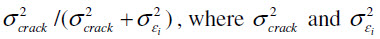

There are three advantages to combining our multiple measures into a single index. First, we are interested in describing the observed patterns of crack’s arrival and fluctuations. Having one summary measure of crack rather than five separate proxies greatly simplifies this task. Second, because each of our individual proxy measures is quite noisy, combining them into a single index substantially increases the signal-to-noise ratio. For instance, in the simplest case where ßi =1 for each proxy, the share of the variance in a given measure that is attributable to a true signal is

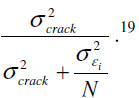

are the variance of the latent crack factor and the measurement error in proxy i respectively. Under the assumption that the measurement errors across proxies are i.i.d, the signal-to-total variance ratio of an equally-weighted index of N proxies is

are the variance of the latent crack factor and the measurement error in proxy i respectively. Under the assumption that the measurement errors across proxies are i.i.d, the signal-to-total variance ratio of an equally-weighted index of N proxies is

A third possible benefit of using a single crack index arises when we turn to estimating the impact of crack on outcomes such as low-birth weight babies or crime rates. Although it might seem that putting each of the individual proxies directly on the right-hand side of such regressions would be preferable (see, for example Lubotsky and Wittenberg 2004), in the plausible scenario in which one or more of our individual proxies may be endogenous to a particular outcome of interest (e.g. when Black youth homicide is on the rise, police departments may respond by intensifying enforcement against drug sellers, holding constant overall crack use), use of an index provides potential benefits by imposing the restriction that each of the proxies has an identical impact on the outcome variable. If the proxies were each entered separately as explanatory variables, one might greatly overstate the role of crack in explaining fluctuations in social outcomes.

In estimating the impact of crack on social outcomes, an attractive alternative to constructing a single index is to instead use the various proxies as instrumental variables for one another. To the extent that the proxies are correlated with the underlying latent variable crack, but the measurement error in the proxies is uncorrelated, the various crack measures are plausible instruments for one another. We present results both using our single index proxy and using an instrumental variables approach.20

One unique feature of our data that we have not yet emphasized, but proves extremely valuable in our analysis, is the fact that crack cocaine was a technological innovation which was virtually unknown until around 1985. This provides us with a well defined pre-crack period. To the extent that our proxies/index are truly reflecting crack, they should have values near zero in the pre-1985 period. In addition, variation in the proxies prior to 1985 is likely to be almost purely measurement error. Comparing the variation in the proxies before and after crack arrives will provide useful insights into the extent to which fluctuations in our proxies after 1985 can plausibly be viewed as signal rather than noise.21

Section IV: The Prevalence of Crack Across Time and Space

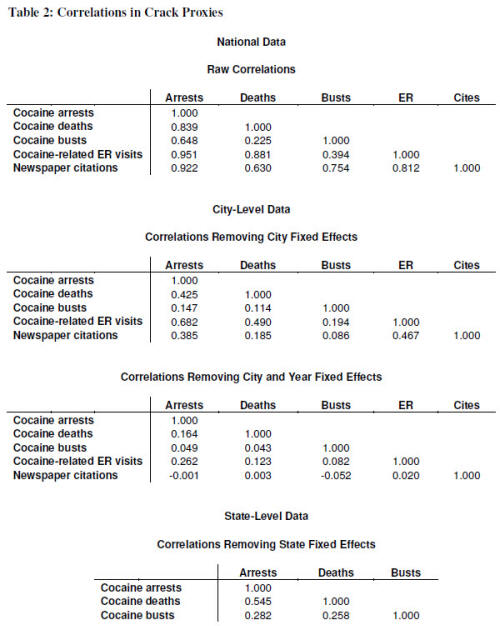

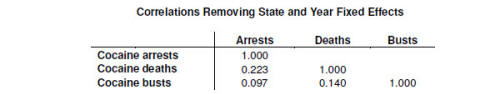

Table 2 presents correlations across the various crack proxies we use in the analysis. The top panel of the table reports correlations across time for the national aggregates of the proxies. Given how similar the time-series patterns are for these variables in Figure 3, it is not surprising that these correlations are high, ranging from .225 to .951. The mean of the off-diagonal elements is equal to .71. The middle panel of the table presents correlations using either the city-year or the state-year as the unit of analysis. City-fixed effects and state-fixed effects have been removed to eliminate systematic and persistent reporting differences across areas. The correlation across the proxies falls, but remains substantial. For both the city and the state sample, all the pairwise correlations remain positive and the mean of the off-diagonal elements is .32 for cities and .36 for states. In other words, when a city or state is high relative to its usual value on one of the proxies in a given year, it tends to be high on all of them – consistent with the hypothesis that a single factor is driving the increase. The bottom panel of the table reports correlations at the city-year and state-year level after removing not only city or state fixedeffects, but also all of the aggregate time series variation using year dummies. Consequently, the correlations in the bottom panel reflect whether a city-year or state-year observation that is high relative to the rest of the sample in that year on one proxy also tends to be high on the other proxies. These correlations are much lower than the others shown in the table. The mean offdiagonal element in the city sample falls to only .07; in the state sample it is .15. The DEA cocaine busts and the newspaper citation index perform particularly poorly. These results highlight the fact that the co-movement of our proxy variables is due in large part to the fact that across many areas, all the proxies tend to be high in some years and low in others.

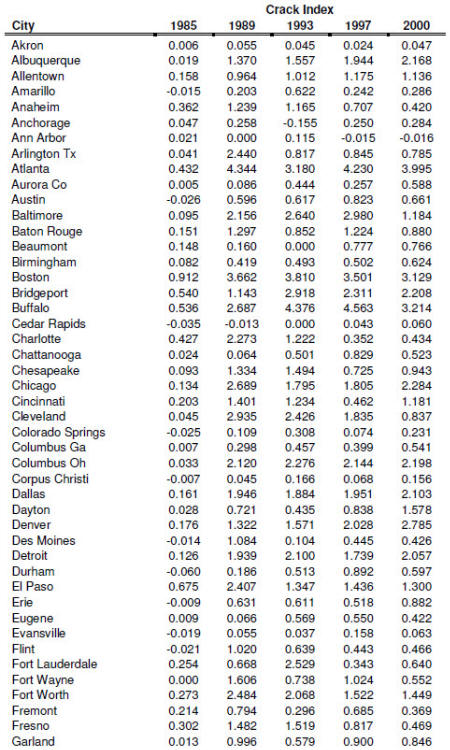

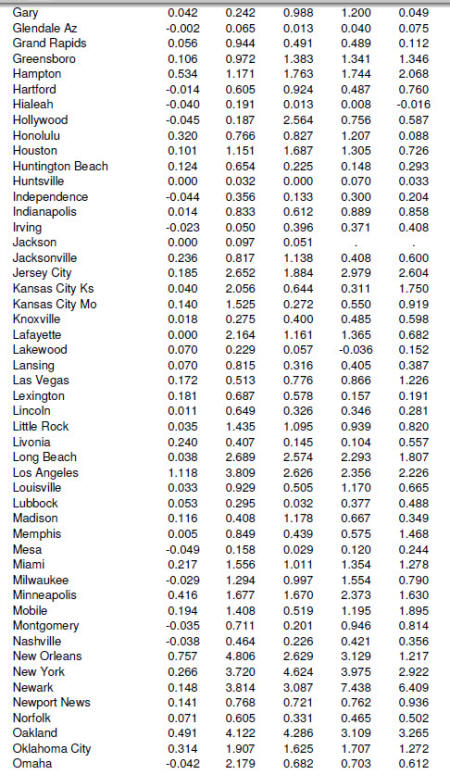

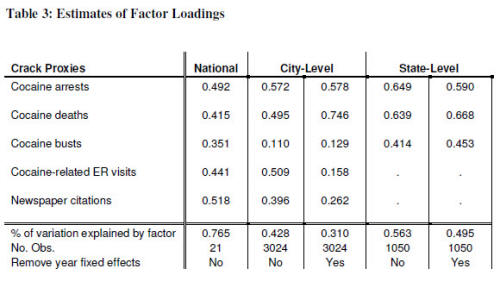

Table 3 presents our baseline estimates of the loadings obtained using factor analysis. The greater is the value corresponding to a particular proxy, the more influence it is given in constructing the crack index. 22 The factor loadings can be negative, although that is not the case for any of our analysis. We report five sets of estimates corresponding to the correlation matrices in Table 3: national aggregates (column 1), city-level data (columns 2 and 3), and state-level data (columns 4 and 5). At the city and state level, we report results before and after year-fixed effects have been removed. For the national aggregates, the loadings are relatively equal across the five proxies. The same is true at the city level before removing year-fixed effects (column 2), except that the DEA cocaine busts proxy receives less weight than the others. When year-fixed effects are taken out, more weight is given to cocaine deaths at the expense of cocaine-related ER visits and, to a lesser extent, crack-related newspaper citations. At the state level, cocaine arrests and cocaine deaths both get high weight and DEA drug busts are given more influence after year-fixed effects are removed.

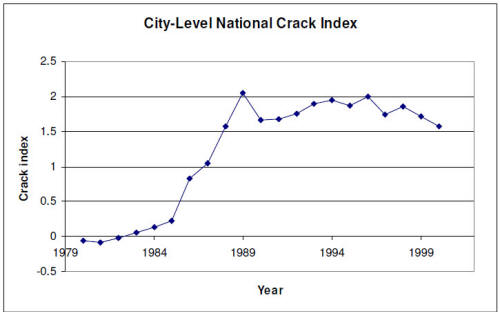

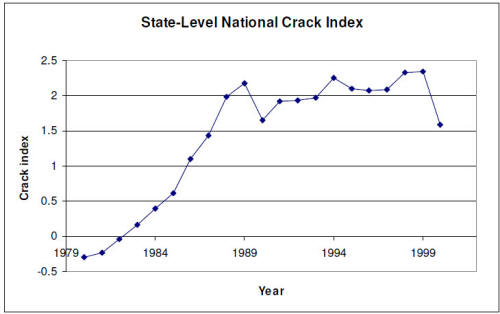

Figure 4 presents population-weighted crack indexes that correspond to the factor analysis loadings for the national-level, city-level and state-level analysis in Table 3. We show results for the specifications without year-fixed effects; the patterns are similar for the other specifications. The crack index is identified only up to a scale of proportionality, so the absolute units of the crack measure are not directly interpretable, nor can they be directly compared across the three figures.

Our results regarding the time-series pattern of crack are not particularly sensitive to the level of aggregation used in the analysis. In all three cases, the crack index is low but rising slightly until 1985, at which point there is a sharp increase to a peak in 1989. The timing of crack’s rise that we estimate corresponds nicely with the anecdotal evidence regarding the introduction of crack cocaine in the mid-1980s and its rapid proliferation. Our estimation technique in no way constrains the estimated crack prevalence to be low in the early years of the data; this result is driven purely by the data. The one noticeable difference between the three indexes is the pattern from 1989-2000. In the top figure using national aggregate data, the index falls almost 50 percent between 1989 and the end of the sample. In the city-level and state-level samples the decline is about 25 percent, with much of the decline coming in latter half of the 1990’s. Regardless of the index, one perhaps surprising result is that our crack index remains so high in 2000, a time in which many casual observers had declared the crack epidemic to have faded. Survey measures of crack usage, however, reinforce our conclusion that crack has not disappeared. The percentage of high school seniors reporting having used crack in the last twelve months fell roughly 30 percent (from 3.1 to 2.2 percent) between 1989 and 2000 (Johnston et al 2004). Eighth and tenth graders in the same survey, who were not asked about crack usage until 1990, reported the highest incidence of annual crack usage in 1999. There is also evidence that sharp declines in the price of crack have led those who use crack to consume it in greater quantities (MacCoun and Reuter 2001).

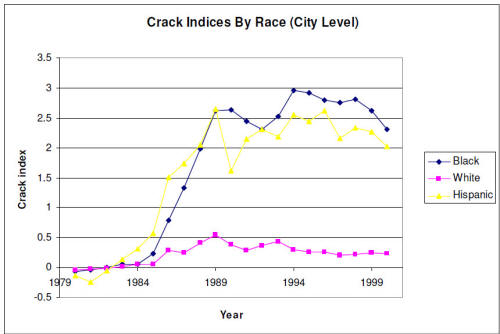

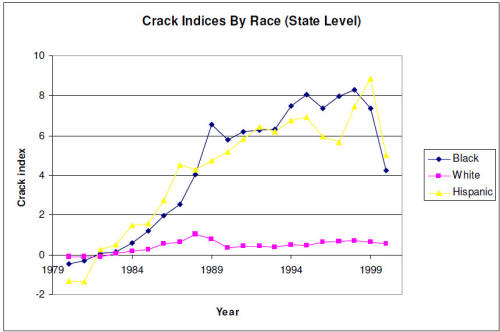

Existing evidence suggests that the impact of crack has been much greater on Blacks and Hispanics than on Whites. Because most of our proxy variables are not available separately by race, we are forced to take an indirect approach to identifying a race-specific crack index. Under the assumption that the loadings on the crack proxies are the same for Blacks and Whites, using the available data we can estimate a model in which the impact of crack varies by race. The overall per capita impact of crack in a city (or state) and year can be decomposed into

(2)

where the P variables represent population shares by race and the coefficients are race- and city-specific crack estimates. captures how our crack index varies across cities at a given point of time as a function of the racial composition of the city; is the value the crack index would take in a hypothetical city all of whose residents were of the race in question. That coefficient does not necessarily directly reflect the relative rates of crack usage across individuals of different races if, for example, the presence of more Blacks in a city is associated with higher crack use by Whites. To estimate the relative impact of crack by race, we run a separate cross-sectional regression for each year with the crack index as the left-hand-side variable and race proportions as the right-hand-side variables, omitting a constant.

where the P variables represent population shares by race and the coefficients are race- and city-specific crack estimates. captures how our crack index varies across cities at a given point of time as a function of the racial composition of the city; is the value the crack index would take in a hypothetical city all of whose residents were of the race in question. That coefficient does not necessarily directly reflect the relative rates of crack usage across individuals of different races if, for example, the presence of more Blacks in a city is associated with higher crack use by Whites. To estimate the relative impact of crack by race, we run a separate cross-sectional regression for each year with the crack index as the left-hand-side variable and race proportions as the right-hand-side variables, omitting a constant.The results of this estimation are reported in Figure 5. For both city- and state-level analyses, crack among Blacks rises until 1989 and then remains relatively steady thereafter. In large cities, the estimated crack index for Whites is consistently 5-10 times lower than Blacks. In the state-level sample, Blacks are again much higher than Whites, and in both samples Hispanics appear roughly comparable to Blacks.

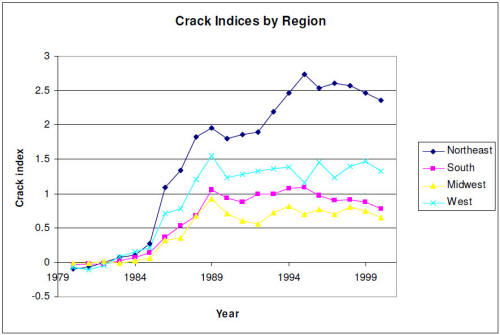

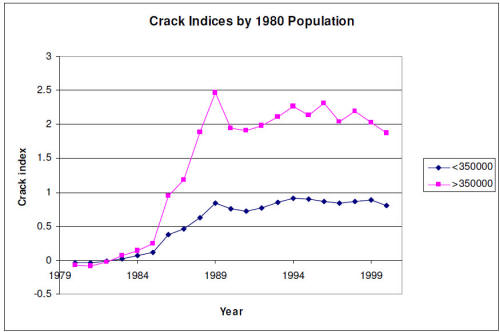

Figures 6 and 7 present crack estimates by region and size of central city respectively. In Figure 6, the Northeast experienced the greatest crack problem, followed by the West. In Figure 7, the time series pattern for crack in cities above and below 350,000 residents is quite similar, except that the crack levels are more than twice as high in the larger cites.23

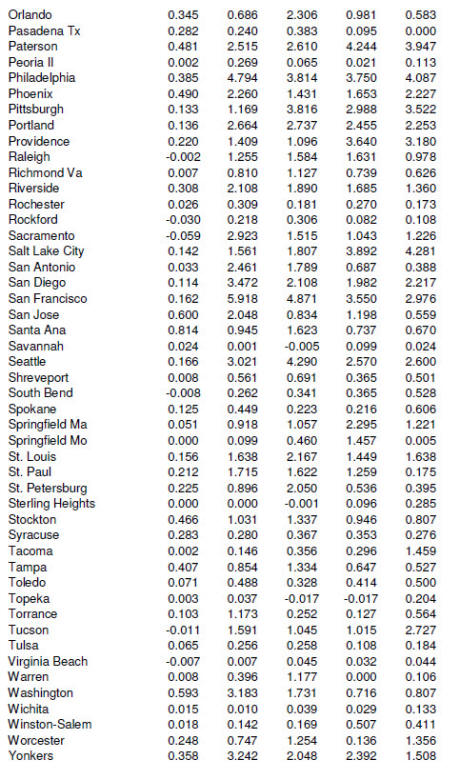

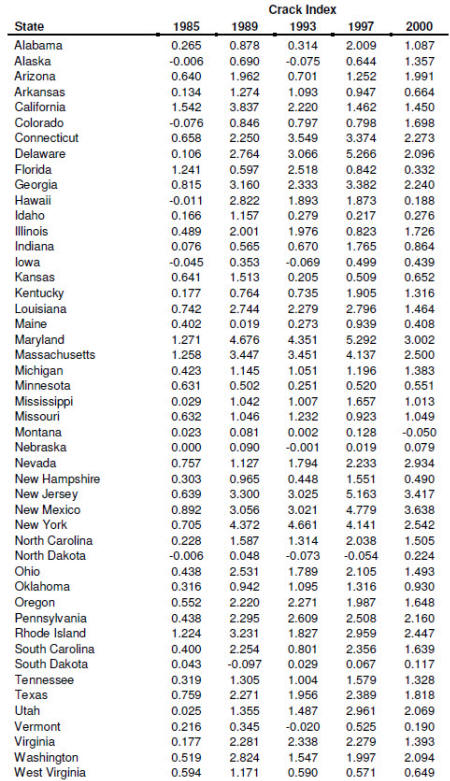

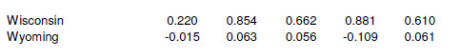

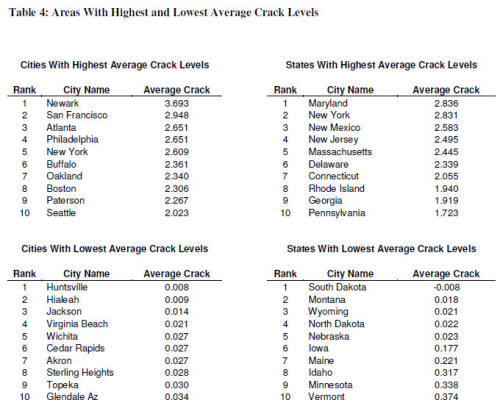

Table 4 reports the cities and states in our sample with the highest and lowest estimated average crack prevalence over the period 1985-2000.24 Because our estimates are noisy at the city-level and the state-level due to substantial measurement error in our proxies, precise rankings must be viewed with the appropriate caution. The set of cities with the greatest crack problem includes cities one might expect: Newark, Philadelphia, New York, and Oakland, for instance. Boston, San Francisco, and Seattle, however, are perhaps surprising.25 Other cities one would expect to rank high such as New Orleans, Baltimore, Washington D.C., and Los Angeles also rank highly, but are not in the top ten. Among states, Maryland and New York head the list. The cities with the least evidence of crack tend to be smaller, geographically isolated cities, but not exclusively cities with low Black populations. Huntsville and Jackson, two of cities with the very low crack estimates, for example, are thirty and seventy percent Black respectively. The states with low crack tend to have large rural populations and few minorities.

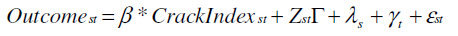

Section V: The Impact of Crack Cocaine

In this section, we attempt to measure the impact that crack had on society by regressing a variety of outcome measures on our estimated crack index and varying combinations of covariates: (3)

where CrackIndex is one of the crack indices we estimated above, and s corresponds to a geographic area (either national, state, or city), and t represents time. One important point to note is that our crack index is a measure of the severity of crack in an area as a whole. This severity can represent both the composition of the population as well as the intensity of use per person. For instance, since crack use appears to be more prevalent among Blacks than Whites, if two cities have the same value on the crack index, but one city has a higher proportion of Whites, the implication is that crack use per Black and crack use per White are likely to be higher in that city than the other city. Consequently, when we examine socio-economic outcomes as dependent variables, the logical specification involves defining outcomes in terms of rates per overall city population. For example, when we examine Black youth homicide, the dependent variable we use is Black youth homicides per 100,000 city residents, not Black youth homicides per Black youth.26

where CrackIndex is one of the crack indices we estimated above, and s corresponds to a geographic area (either national, state, or city), and t represents time. One important point to note is that our crack index is a measure of the severity of crack in an area as a whole. This severity can represent both the composition of the population as well as the intensity of use per person. For instance, since crack use appears to be more prevalent among Blacks than Whites, if two cities have the same value on the crack index, but one city has a higher proportion of Whites, the implication is that crack use per Black and crack use per White are likely to be higher in that city than the other city. Consequently, when we examine socio-economic outcomes as dependent variables, the logical specification involves defining outcomes in terms of rates per overall city population. For example, when we examine Black youth homicide, the dependent variable we use is Black youth homicides per 100,000 city residents, not Black youth homicides per Black youth.26There are two obvious shortcomings associated with the simple OLS approach that we adopt. The first is that our crack index may suffer from measurement error, which will bias the estimates of crack’s impact, most likely in a downward direction. The second weakness of this approach is that the estimates we obtain reflect correlations, rather than true causal impacts. It is possible that omitted variables such as the erosion of social networks or the decline of two-parent households affects both crack and outcomes like homicide or children in foster care.

Instrumenting one proxy using the others provides a means of dealing with the issue of measurement error, under the assumption that the measurement error in the different proxies are uncorrelated (conditional on the other controls included in the regression). It is important to note, however, that this instrumenting strategy is unlikely to help in providing estimates that are directly interpretable as causal in nature. To the extent that omitted variables or reverse causality lead one of the crack proxies to be correlated with the error term in equation (3), it is likely that all of the crack proxies will suffer the same weakness.

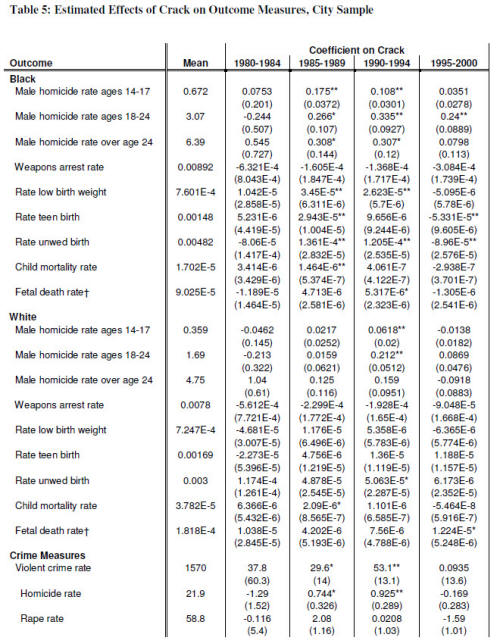

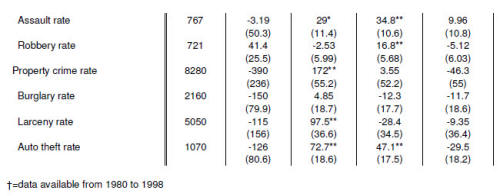

Table 5 shows results from estimating equation (3) on our city-level sample using the city-level crack index. Each row of the table corresponds to a different outcome variable. The first column of the table reports the mean of the dependent variable in the sample; because our outcomes are denominated by the entire city population (not just Blacks or Whites depending on which race we are looking at), the reported means for both races are less than if the variables were per member of the group. Because Blacks make up a smaller percentage of the population, the reported means are particularly small relative to a rate per capita for Blacks. We allow the estimated coefficient on the crack index to vary by time period; columns 2-5 of the table report the coefficients for the periods 1985-1989, 1990-1994, and 1995-2000 respectively.27 All specifications include city-fixed effects, year dummies, and controls for percent of the population that is Black and Hispanic, log population, and log per capita income. Standard errors, shown in parentheses, take into account AR1 serial correlation within cities over time.

The top panel of Table 5 reports outcomes for Blacks. The crack index is positively associated with eight of the nine outcomes we examine in the 1985-1989 time period, with statistically significant estimates at the .01 level in five of the cases. A similar pattern of estimates is present in the 1990-1994 period. After 1995, however, the link between the crack index and these social outcomes for Blacks disappears--more than half of the point estimates become negative in the last period, and only the male age 18-24 homicide rate has a positive and significant coefficients. The middle panel of Table 5 shows city-level estimates for Whites. Although the crack index is generally positively correlated with these outcomes after 1985 (21 of the 27 point estimates are positive), only 5 of the 27 coefficients are statistically different than zero. The bottom panel of the table analyzes results for overall crime rates, which are not separately available by race. The crack index is positively correlated with eight of nine crime categories from 1985-1989, six significantly, and seven of the nine categories from 1990-1994, but the estimated coefficients decline in magnitude and statistical significance in the final period for all categories of crime.

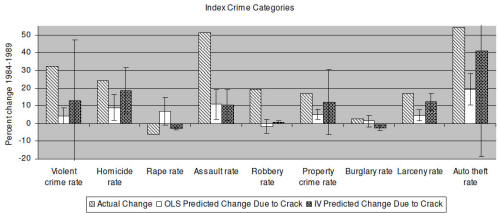

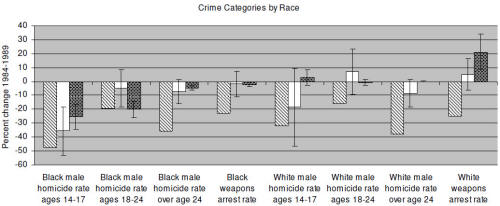

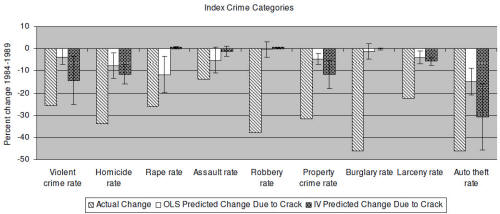

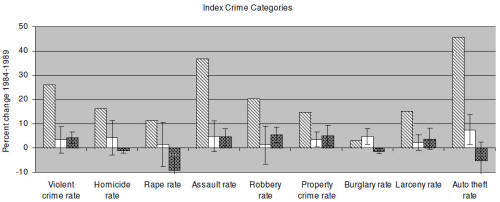

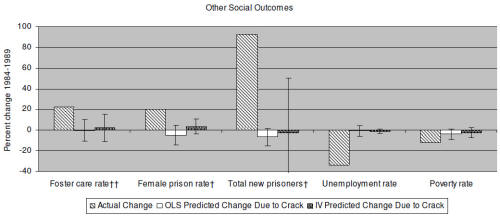

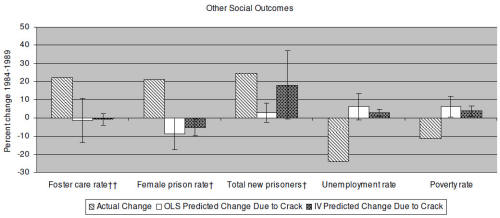

To aid in interpreting the magnitude of the effects implied by the coefficients in Table 5, we report graphically the fraction of the observed variation in the outcomes that can be accounted for by the crack index over the period in which crack rose sharply (1984-1989) in Figure 8, and from the peak of crack to the end of the sample (usually 1989-2000) in Figure 9. In these figures, we compare the observed percent changes for the crime and birth-related outcomes over these time periods to the implied impact of crack calculated in one of two ways: (1) using the crack index as in Table 5, and (2) instrumenting for cocaine arrests using the other crack proxies as instruments.28 The implied impact of crack from the OLS specification in a particular year is the product of the regression coefficient in Table 5 multiplied by the average value of the crack index in that year. The impact of crack between 1984 and 1989 is simply the difference between the measured impact of crack in 1989 and in 1984. Calculating the impact of crack in the instrumental variables regressions is done in a similar manner, with the added complication related to measurement error in the cocaine arrests proxy.29 The corresponding standard error bands are shown in the figure as well.

A number of important points emerge from Figure 8. First, comparing the columns shaded white (OLS estimates) and the columns shaded black (instrumental variables estimates), in most cases the IV estimates are larger than the OLS estimates, although less precisely estimated. These generally larger IV estimates are consistent with the presence of measurement error in our index, leading to attenuation bias in our OLS results. Second, the magnitude of the actual percentage increase in homicide rates among young Black males is far greater than for the other variables considered. Our measure of crack cocaine explains a substantial part of this increase, particularly in the instrumental variables specifications. According to our IV estimates, crack can account for a 100-155 percent increase in Black male homicides among those aged 18- 24, and a change of 55-125 percent for Black male homicide among those aged 14-17. In contrast, our crack measure accounts for only small changes in older Black male homicide and White homicide. Third, for the birth/childhood outcomes, the impact of crack is larger for Blacks than for Whites, but the results are not as stark as for homicide. We estimate that the rise in crack between 1984 and 1989 accounts for roughly one-third of the increase in low birth weight Black babies, less than one-third of the Black rate of unwed births, much or all of the increase in Black child mortality and fetal death. For Whites, there is some apparent positive association between crack and low birth weight babies and child mortality. Finally, we find a positive relationship between crack and a wide range of crimes, although the magnitude is small when compared to the impact on Black youth homicide. In the OLS specifications, violent crime and property crime are both estimated to have increased by roughly 4 percent due to crack over the period 1984-1989; in the IV specifications the increase is approximately 10 percent, but very imprecisely estimated.

Figure 9 shows the estimated impact of changes in crack on the same set of outcomes for the period 1989-2000. One-half to three-fourths of the decline in homicide by Black males aged 14-17 can be attributed to the combined impact of a decline in the level of the crack index, and more importantly, the weakening of the link between crack and violence. By the year 2000, most of the crack-related spike in youth homicide in the late 1980s was gone--because the baseline level of youth homicide is almost three times higher in 1989 than in 1984, a 34 percent decrease in the latter period is equal and opposite to almost a 100 percent increase in the earlier period in terms of number of homicides. For older criminals and Whites, the impact of receding crack does not consistently explain a substantial fraction of the observed homicide declines in the 1990s. For Blacks, the adverse effects of crack on birth outcomes in the 1980s are essentially undone in the 1990s. The impacts on White birth outcomes are small and carry mixed signs. For city-level crime measures, the reductions attributable to crack in the 1990s erase much, but often not all, of the crack-driven increases in the 1980s. The notable exception to this pattern is the IV estimate on violent crime, which suggests that violent crime rose (although not statistically significantly) in the 1990s as crack receded (because the estimated impact of crack on violent crime is negative in the 1990s).

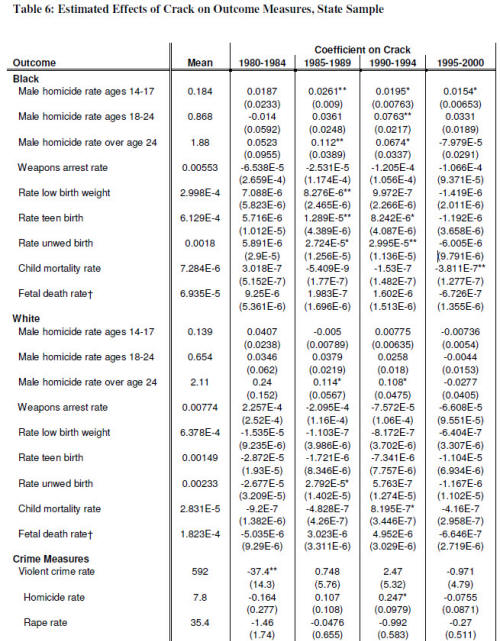

Table 6 replicates the analysis of Table 5, but using states as the unit of analysis rather than our sample of large cities. The regression results in Table 5 are quite similar to what we found for large cities; crack has the greatest impact on Black youth homicide, tends to be positively related to adverse birth outcomes for Blacks and is not significantly related to most outcomes for Whites. The impact of crack once again weakens over time. One important difference relative to the city sample is that overall crime is not positively and statistically related to crack in the state sample. In addition, there is less evidence of a strong impact of crack on Black birth outcomes outside of the large cities. A number of additional outcome measures are available at the state level: foster care rates, new prison commitments, unemployment rates, and poverty rates. None of these outcomes reveals a pattern suggestive of an important impact of crack in the expected direction. The negative relationship between crack and new prison commitments, while perhaps surprising given the enormous increase in drug-related incarceration over this period, hints at the possibility that aggressive punishment of drug sellers may have reduced the severity of the crack epidemic. In other words, the negative coefficient in the prison regression may primarily reflect reverse causality running from imprisonment to crack, rather than vice versa.

Figures 10 and 11 report the fraction of the observed variation in the outcomes at the state level that can be explained by the crack index for the periods 1984-1989, and 1989-2000. Not surprisingly given that crack was concentrated in large cities, the rise and fall of crack has less explanatory value at the state level. For instance, the crack index explains less than one-third of the overall rise in young Black male homicide at the state level, and only one-fifth of the increase in Black low birth weight babies. Overall, comparing the results in Figures 8-11, and noting that about 16 percent of the U.S. population resides in cities included in our city sample, we estimate that about 70 percent of the adverse impact of crack was felt in large cities, implying that the rates per capita were at least 10 times higher in large cities than in the rest of the country.

Section VI: Conclusion

A number of social, criminological, and economic variables experienced negative shocks in the late 1980s and early 1990s, particularly among Blacks. We find evidence consistent with the hypothesis that the rise of crack cocaine played an important contributing role. To overcome the absence of a reliable quantitative measure of crack, we construct a crack index based on a set of imperfect, but plausible proxies. This crack index reproduces many of patterns described in journalistic and ethnographic accounts including the timing of the crack epidemic and the disproportionate impact on Blacks and Hispanics. We find a strong link between our measure of crack and increased homicide rates by the young, especially among Blacks, in the late 1980s. During that time period, our crack index is also associated with adverse outcomes for babies – especially Black babies. By the early 1990s, however, the relationship between crack and unwelcome social outcomes had largely disappeared. Thus, though crack use persisted at high levels, it did so with relatively minor measurable social consequences. This finding is consistent with an initially high level of crack-related violence as markets responded to the changes in distribution methods associated with the technological shock that crack represented. After property rights were established and crack prices fell sharply reducing the profitability of the business, competition-related violence among drug dealers declined.

One explanation for the weakening relationship between the crack index and birth outcomes is the changing composition of crack users. Following its introduction, crack use was overwhelmingly a drug of adolescents and young adults, and its use was widespread. For instance, 7.2 percent of respondents in the National Household Survey on Drug Use and Health (SAMHSA 2003b) who were 18-22 in 1985 report lifetime crack usage, compared to only 2.8 percent of those who were 33-37 years old in 1985. Later cohorts also use crack at much lower rates than the first cohorts exposed to crack. In 2002, 0.6 percent of the age group that was 18- 22 in 1985 (and by 2002 was 35-39 years old) had used crack in the last month. In stark contrast, less than 0.2 percent of the 18-22 year olds in 2002 report using crack in the prior month. As crack addicts aged, fewer were in the high fertility age group. Presumably, as the dangers of crack to the fetus became clear, women intending to get pregnant may have avoided crack and those using crack may have been less likely to take a pregnancy to term.

If the rise of crack indeed exerted an important influence on social outcomes over the last two decades, then an obvious concern is that studies examining these outcomes which fail to adequately control for crack may generate misleading conclusions. Ayres and Donohue (2003), for instance, conjecture that the findings of Lott and Mustard (1997) and Lott (2000) regarding the impact of concealed weapons laws are spurious, driven by the omitted variable crack cocaine. Sailer (1999) and Joyce (2004) level the same charges at Donohue and Levitt’s (2001) analysis of the impact of legalized abortion on crime. An important application of the crack index we construct is as a control variable in future research.

Appendix

Data

This paper uses data from the 144 cities with population above 100000 in 1980 and the 50 U.S. States. The following table describes the data used in paper.

* Cocaine deaths include accidental poisonings, suicides, and other deaths for which cocaine use was coded as a primary or contributing factor. Prior to 1989, deaths were classified using the International Classification of Diseases 9th revision (ICD-9); starting in 1999 deaths were coded using the 10th revision. Cocaine death entries under ICD-9 include ICD codes 8552, 3042, and 3056 as well as ICD codes 8501-8699, 9501-9529, 9620-9629, 972, 9801-9879, 3050-3054, 3057-3059 with a secondary code of 9685. Cocaine deaths under ICD-10 include codes F140-F149 and F190-F199, X42, X44, X62, X64, X85, Y12, and Y14 with secondary code T405. For more information on counting drug-related deaths see Lois Fingerhut & Christine Cox, "Poisoning mortality, 1985-1995", Public Health Reports 113:3, 1998.

** Cocaine busts were defined as busts with primary drug code 9041 and secondary drug codes L000, L005, L010, L269, L900, and L920

Estimating the Crack Index

The procedure for estimating the crack index is:

1. Remove city or state fixed effects from each of the crack proxies. Readjust each proxy to have a grand mean of 0 during the period from 1980-1984.

2. Normalize each of the proxies to have unit variance. This eliminates differences in units of measure across proxies.

3. The factor loadings ( i) and scores (Zst) satisfy the relationship:

Here i indexes a proxies, s a location, and t a time period. We require a scale restriction to separately identify the loadings and scores. In our analysis, we impose that the sum of the squared loadings is one.

4. Select an initial value for the loadings.

5. Stack each of the available proxies at a particular location/time. Use least squares regression across the proxies to estimate the value of the crack index (score) at each location/time. These regressions are within a location/time, across measures.

6. The squared loadings measure the extent to which each of the proxies contributes to the overall crack index. To account for missing data, at each location/time, multiply the scores calculated in step 5 by

, where Yi represents the loading associated with proxy i and the summation is made over all available proxies at that location/time.

, where Yi represents the loading associated with proxy i and the summation is made over all available proxies at that location/time.7. Regress each proxy on the scores calculated in step 5 to generate a new estimate of the loading associated with that proxy. These regressions are within a particular measure, across locations/times.

8. Re-normalize the estimated loadings to satisfy the scale restriction.

9. Repeat steps 5-8 until the loadings converge.30

10. Test multiple initial choices for loadings to ensure that the convergent result is optimal in the sense of minimizing the sum of the squared residuals in (1).

It is important to note that constructed in this manner the absolute mean and variance of the crack index are arbitrary.

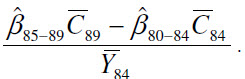

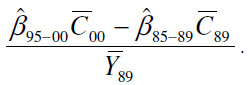

denote the mean crack index in 1989, and

denote the mean crack index in 1989, and  denote the mean value of the outcome of interest in 1984. The predicted change is constructed as

denote the mean value of the outcome of interest in 1984. The predicted change is constructed as  The IV predicted changes are constructed similarly, except that the coefficients are based on an instrumental variables strategy in which cocaine arrests are used as the right-hand-side variable in equation (3) and a crack index constructed using the other crack proxies is used as an instrumental variable. In calculating the implied impact of crack using IV, only the portion of the observed variation in cocaine arrests attributable to variation in crack is relevant. It can be shown that algebraically this equates to scaling down the full variation in cocaine arrests by the signal to signal- plus-noise ratio in cocaine arrests. This signal to signal-plus-noise ratio can be computed from the variance-covariance matrix of the crack proxies, combined with a scaling adjustment across proxies that can be inferred from the ratio of the IV estimates when one proxy is used as the instrument and the other variable is instrumented versus when the roles of the two variables are reversed. OLS and IV regressions include controls for percent of the population Hispanic, percent of the population Black, log population, and log per capita income as well as city and year fixed effects. The whiskers display 95% confidence intervals for the OLS and IV estimated effects. To facilitate comparison of effect sizes across social outcomes, in some cases confidence intervals were permitted to extend beyond the bounds of the plots. The OLS estimates were estimated allowing AR(1) serial correlation in the error terms; IV standard errors were obtained via the bootstrap.

The IV predicted changes are constructed similarly, except that the coefficients are based on an instrumental variables strategy in which cocaine arrests are used as the right-hand-side variable in equation (3) and a crack index constructed using the other crack proxies is used as an instrumental variable. In calculating the implied impact of crack using IV, only the portion of the observed variation in cocaine arrests attributable to variation in crack is relevant. It can be shown that algebraically this equates to scaling down the full variation in cocaine arrests by the signal to signal- plus-noise ratio in cocaine arrests. This signal to signal-plus-noise ratio can be computed from the variance-covariance matrix of the crack proxies, combined with a scaling adjustment across proxies that can be inferred from the ratio of the IV estimates when one proxy is used as the instrument and the other variable is instrumented versus when the roles of the two variables are reversed. OLS and IV regressions include controls for percent of the population Hispanic, percent of the population Black, log population, and log per capita income as well as city and year fixed effects. The whiskers display 95% confidence intervals for the OLS and IV estimated effects. To facilitate comparison of effect sizes across social outcomes, in some cases confidence intervals were permitted to extend beyond the bounds of the plots. The OLS estimates were estimated allowing AR(1) serial correlation in the error terms; IV standard errors were obtained via the bootstrap.

denote the mean crack index in 1989, and

denote the mean crack index in 1989, and  denote the mean value of the outcome of interest in 1989. The predicted change is constructed as

denote the mean value of the outcome of interest in 1989. The predicted change is constructed as For outcomes that were not available through 2000 the change from 1989 through the final year of available data is reported in the final column. The IV predicted changes are constructed similarly, except that the coefficients are based on an instrumental variables strategy in which cocaine arrests are used as the right-hand-side variable in equation (3) and a crack index constructed using the other crack proxies is used as an instrumental variable. In calculating the implied impact of crack using IV, only the portion of the observed variation in cocaine arrests attributable to variation in crack is relevant. It can be shown that algebraically this equates to scaling down the full variation in cocaine arrests by the signal to signal- plus-noise ratio in cocaine arrests. This signal to signal-plus-noise ratio can be computed from the variance-covariance matrix of the crack proxies, combined with a scaling adjustment across proxies that can be inferred from the ratio of the IV estimates when one proxy is used as the instrument and the other variable is instrumented versus when the roles of the two variables are reversed. OLS and IV regressions include controls for percent of the population Hispanic, percent of the population Black, log population, and log per capita income as well as city and year fixed effects. The whiskers display 95% confidence intervals for the OLS and IV estimated effects. To facilitate comparison of effect sizes across social outcomes, in some cases confidence intervals were permitted to extend beyond the bounds of the plots. The OLS estimates were estimated allowing AR(1) serial correlation in the error terms; IV standard errors were obtained via the bootstrap.

For outcomes that were not available through 2000 the change from 1989 through the final year of available data is reported in the final column. The IV predicted changes are constructed similarly, except that the coefficients are based on an instrumental variables strategy in which cocaine arrests are used as the right-hand-side variable in equation (3) and a crack index constructed using the other crack proxies is used as an instrumental variable. In calculating the implied impact of crack using IV, only the portion of the observed variation in cocaine arrests attributable to variation in crack is relevant. It can be shown that algebraically this equates to scaling down the full variation in cocaine arrests by the signal to signal- plus-noise ratio in cocaine arrests. This signal to signal-plus-noise ratio can be computed from the variance-covariance matrix of the crack proxies, combined with a scaling adjustment across proxies that can be inferred from the ratio of the IV estimates when one proxy is used as the instrument and the other variable is instrumented versus when the roles of the two variables are reversed. OLS and IV regressions include controls for percent of the population Hispanic, percent of the population Black, log population, and log per capita income as well as city and year fixed effects. The whiskers display 95% confidence intervals for the OLS and IV estimated effects. To facilitate comparison of effect sizes across social outcomes, in some cases confidence intervals were permitted to extend beyond the bounds of the plots. The OLS estimates were estimated allowing AR(1) serial correlation in the error terms; IV standard errors were obtained via the bootstrap.

denote the mean crack index in 1989, and

denote the mean crack index in 1989, and  denote the mean value of the outcome of interest in 1984. The predicted change is constructed as

denote the mean value of the outcome of interest in 1984. The predicted change is constructed as  The IV predicted changes are constructed similarly, except that the coefficients are based on an instrumental variables strategy in which cocaine arrests are used as the right-hand-side variable in equation (3) and a crack index constructed using the other crack proxies is used as an instrumental variable. In calculating the implied impact of crack using IV, only the portion of the observed variation in cocaine arrests attributable to variation in crack is relevant. It can be shown that algebraically this equates to scaling down the full variation in cocaine arrests by the signal to signal- plus-noise ratio in cocaine arrests. This signal to signal-plus-noise ratio can be computed from the variance-covariance matrix of the crack proxies, combined with a scaling adjustment across proxies that can be inferred from the ratio of the IV estimates when one proxy is used as the instrument and the other variable is instrumented versus when the roles of the two variables are reversed. OLS and IV regressions include controls for percent of the population Hispanic, percent of the population Black, log population, and log per capita income as well as state and year fixed effects. The whiskers display 95% confidence intervals for the OLS and IV estimated effects. To facilitate comparison of effect sizes across social outcomes, in some cases confidence intervals were permitted to extend beyond the bounds of the plots. The OLS estimates were estimated allowing AR(1) serial correlation in the error terms; IV standard errors were obtained via the bootstrap.

The IV predicted changes are constructed similarly, except that the coefficients are based on an instrumental variables strategy in which cocaine arrests are used as the right-hand-side variable in equation (3) and a crack index constructed using the other crack proxies is used as an instrumental variable. In calculating the implied impact of crack using IV, only the portion of the observed variation in cocaine arrests attributable to variation in crack is relevant. It can be shown that algebraically this equates to scaling down the full variation in cocaine arrests by the signal to signal- plus-noise ratio in cocaine arrests. This signal to signal-plus-noise ratio can be computed from the variance-covariance matrix of the crack proxies, combined with a scaling adjustment across proxies that can be inferred from the ratio of the IV estimates when one proxy is used as the instrument and the other variable is instrumented versus when the roles of the two variables are reversed. OLS and IV regressions include controls for percent of the population Hispanic, percent of the population Black, log population, and log per capita income as well as state and year fixed effects. The whiskers display 95% confidence intervals for the OLS and IV estimated effects. To facilitate comparison of effect sizes across social outcomes, in some cases confidence intervals were permitted to extend beyond the bounds of the plots. The OLS estimates were estimated allowing AR(1) serial correlation in the error terms; IV standard errors were obtained via the bootstrap.

denote the mean crack index in 1989, and

denote the mean crack index in 1989, and  denote the mean value of the outcome of interest in 1989. The predicted change is constructed as

denote the mean value of the outcome of interest in 1989. The predicted change is constructed as  The IV predicted changes are constructed similarly, except that the coefficients are based on an instrumental variables strategy in which cocaine arrests are used as the right-hand-side variable in equation (3) and a crack index constructed using the other crack proxies is used as an instrumental variable. In calculating the implied impact of crack using IV, only the portion of the observed variation in cocaine arrests attributable to variation in crack is relevant. It can be shown that algebraically this equates to scaling down the full variation in cocaine arrests by the signal to signal- plus-noise ratio in cocaine arrests. This signal to signal-plus-noise ratio can be computed from the variance-covariance matrix of the crack proxies, combined with a scaling adjustment across proxies that can be inferred from the ratio of the IV estimates when one proxy is used as the instrument and the other variable is instrumented versus when the roles of the two variables are reversed. OLS and IV regressions include controls for percent of the population Hispanic, percent of the population Black, log population, and log per capita income as well as state and year fixed effects. The whiskers display 95% confidence intervals for the OLS and IV estimated effects. To facilitate comparison of effect sizes across social outcomes, in some cases confidence intervals were permitted to extend beyond the bounds of the plots. The OLS estimates were estimated allowing AR(1) serial correlation in the error terms; IV standard errors were obtained via the bootstrap.

The IV predicted changes are constructed similarly, except that the coefficients are based on an instrumental variables strategy in which cocaine arrests are used as the right-hand-side variable in equation (3) and a crack index constructed using the other crack proxies is used as an instrumental variable. In calculating the implied impact of crack using IV, only the portion of the observed variation in cocaine arrests attributable to variation in crack is relevant. It can be shown that algebraically this equates to scaling down the full variation in cocaine arrests by the signal to signal- plus-noise ratio in cocaine arrests. This signal to signal-plus-noise ratio can be computed from the variance-covariance matrix of the crack proxies, combined with a scaling adjustment across proxies that can be inferred from the ratio of the IV estimates when one proxy is used as the instrument and the other variable is instrumented versus when the roles of the two variables are reversed. OLS and IV regressions include controls for percent of the population Hispanic, percent of the population Black, log population, and log per capita income as well as state and year fixed effects. The whiskers display 95% confidence intervals for the OLS and IV estimated effects. To facilitate comparison of effect sizes across social outcomes, in some cases confidence intervals were permitted to extend beyond the bounds of the plots. The OLS estimates were estimated allowing AR(1) serial correlation in the error terms; IV standard errors were obtained via the bootstrap.