The Apocalypse of Adolescenceby Ron Powers

The Atlantic

March 2002

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHTYOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ

THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

This spring one of two Vermont teenagers charged with the knifing murder of two Dartmouth College professors will go on trial. The case offers entry to a disturbing subject—acts of lethal violence committed by "ordinary" teenagers from "ordinary" communities, teenagers who have become detached from civic life, saturated by the mythic violent imagery of popular culture, and consumed by the dictates of some private murderous fantasy.

Easing around a curve along Route 110, about eight miles north of Tunbridge, Vermont, one is likely to be transfixed—wounded, almost—by the prospect that sweeps into view: a plain and weathered yet elegant New England village undulates for half a mile along a thoroughfare, hardly wider than a couple of house lots on either side. Lining the road are manicured playing fields, a spare and handsome town hall, a century-old white frame church (Congregational-Methodist), a couple of school buildings, a harness shop, two greens, the county courthouse, stately houses of brick and wood, a modest restaurant, and a gas station. Steep mountains press in on either side of the village, and arcing through its western flank is a splendid little stream. More stately houses are visible halfway up the slope of the western mountain, tucked among pine trees. To the east a pine wilderness hovers above the town, giving way at the southern edge to a nearly vertical cemetery, its oldest tombstones commemorating Union dead. This is Chelsea, Vermont, the shire town of Orange County, chartered on August 4, 1781, population 1,250. It scarcely has the look of a town that would breed teenage killers.

Americans want to believe in towns like Chelsea. My wife and I moved to Vermont from New York City in 1988, in search of such a place. We came here for several reasons, but coloring all of them was the hope of raising our two young sons in the safety and harmony of a tight-knit town community. It wasn't an unreasonable expectation. In the 1980s and 1990s, as the nation's celebrated "rural rebound" established itself, Vermont had been ranked at or near the top of America's "safest" and "most livable" states. Vermont's largest city, Burlington, was singled out as a "Dream Town" (Outside magazine), received a City Livability Award (the U.S. Conference of Mayors), and was designated a "kid-friendly city" (Zero Population Growth). The state was recognized for its superior air quality by the Corporation for Enterprise Development. These surveys drew heavily on the perceived needs of children. Public safety headed almost every list of desirable characteristics. Other leading indicators were pupil-teacher ratios in the public schools, high school graduation rates, funding levels for the arts and for education in general, marriage and divorce rates, and birth rates among teenagers. And underlying all of this was the fact that happy children and Vermont are linked in American myth, in large part because Norman Rockwell, who lived in the town of Arlington, Vermont, for fifteen years, employed local boys and girls as models for his illustrations of leapfrogging, flag-saluting, Christmas-caroling American children.

According to a survey conducted in 1995, 41 percent of the U.S. population would eventually like to move to a small town or rural area. Not everybody can do it, of course; the potential loss of livelihood is usually too great a risk. But for those who try it, Vermont offers many sources of replenishment. A tiny state (9,609 square miles), it is sparsely populated, with fewer than 600,000 people. Its annual tourist flow dwarfs the local population. The heart of the state lies in remote mountain villages like Chelsea. Parents sometimes practice small-scale farming, or teach, or work as artisans, or join in the kind of "home economics" envisioned by the essayist Wendell Berry: a cooperative effort to maintain a purely local system of life. The children—well, the children, being the point of it all, are expected to mature smoothly into thoughtful, self-reliant adults, at peace with themselves and with the world.

Those are the expectations. If, indeed, the prospects for a happy childhood remain alive and well in havens like Vermont, they might imply a model of sorts for the many people in this country who have an anxious relationship with their children.

But what if they do not?

The Zantop MurdersLast year, on a wintry Saturday, January 27, a popular academic couple at Dartmouth College, in Hanover, New Hampshire, just across the Connecticut River from Vermont, made preparations for a dinner party, one of many they had hosted in their house on the woodsy slopes of Etna, a town a few miles from Hanover. Both were German immigrants. They had made their house a salon for faculty members, students, and visitors to the college. Susanne Zantop, who was fifty-five, was the chair of the Department of German Studies. Her husband, Half, sixty-two, was a professor of earth sciences. At around six that evening the first dinner guest arrived. Venturing inside, she discovered Half and Susanne lying in their own blood in their study. They had been repeatedly stabbed in the head, neck, and chest.

Over the three weeks following the attack, as the police combed the region but kept silent about the progress of the investigation, Dartmouth students and Hanover townspeople struggled against fear. Nearly everyone assumed that the killer remained in the vicinity—a troubled student, perhaps, or a faculty rival. A suspicious figure was spotted lurking around dormitories. A suspicious car with out-of-state license plates was reported. Members of the national media converged on the town, filled local hotel rooms, invaded Dartmouth dorms with cameras and notepads, seeking leads, quotations, rumors, irony. When the FBI joined the investigation, the range of conjecture went national and then international. Theories of a Holocaust tie-in circulated: the Zantops were political liberals who often argued that their native country should be more forthright in confronting the evils of its Nazi past. Had they been murdered by a vengeful neo-Nazi?

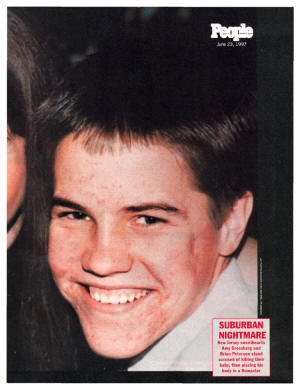

On February 16 the New Hampshire attorney general announced that an arrest warrant had at last been issued: not for a troubled member of the Dartmouth community but for a seventeen-year-old boy, Robert Tulloch, from Chelsea, about thirty miles north of Hanover. Three days later Robert and his sixteen-year-old friend Jimmy Parker were arrested a little before dawn at a truck stop in New Castle, Indiana. The police there had picked up a truck driver's CB radio call soliciting a ride for two young hitchhikers he was carrying, who were intent on making it to California. Robert was the president of his student council. Jimmy was an artistic youth who played the bass guitar and acted in school plays.

Robert and Jimmy, it turned out, both had families who had come to Vermont in pursuit of the dream of harmony. John Parker, a native of Poughkeepsie, New York, and his wife, Joan, who was reared in San Diego, had arrived in Chelsea about twenty-five years earlier. "They literally picked Chelsea out on a map," a neighbor who knows them well told me recently. John, educated at Ohio Wesleyan University, had taken up carpentry, at which he excelled. Over the years he had either built or renovated many of the houses in Chelsea. He chaired the Chelsea Recreation Committee, which secured the money and the unbilled labor to create the manicured fields at the southern entrance to the town, and he did much of the manicuring himself—regularly watering the grass and cutting it with a riding mower. He also built the town picnic shelter.

Robert Tulloch's parents had arrived from Florida to take up residence in Vermont. They had lived in Chelsea for about nine years. His father, Michael, was a furniture maker, a specialist in Windsor chairs. His mother, Diane, was a nurse affiliated with the Visiting Nurse Association, a group with connections to the Dartmouth-Hitchcock Medical Center. Her neighbors knew her as a gentle mother of four, a maker of soap, a raiser of chickens—"very granola," in the words of one.

But the nurturing virtues of small-town Vermont life failed to ennoble Robert and Jimmy. According to the prosecution, the two entered the Zantop household armed with keenly sharpened foot-long SOG Seal 2000 combat knives. Attacking the couple in the small confines of their study, the boys allegedly hacked away at them, slashing repeatedly at their heads, necks, and chests. The knives later turned up in Robert's bedroom, bearing traces of blood that provided a DNA match with that of Susanne Zantop. Internet records revealed that Jimmy had bought the knives just weeks earlier. A fingerprint on a chair at the Zantop home was identified as Robert's. A boot print in the house matched a boot belonging to Robert. And blood found on the floor mat of a 1996 Subaru registered to Jimmy's parents revealed Susanne Zantop's DNA. A car of similar description had been sighted earlier at the scene of the crime. Jimmy has pled guilty to one count of second-degree murder and will testify at Robert's trial, which is scheduled for this spring. Robert is charged with two counts of first-degree murder.

A Cluster of AssaultsIn their unvexed small-town habitat, and in the apparent absence of any motivating passions, Robert Tulloch and Jimmy Parker may come to be seen as representatives of a new mutation in the evolution of the murderous American adolescent. In this mutation the murderers' victims tend not to be the denizens of an urban war zone. Instead the victims are likely to be people living quietly in small towns or suburbs—unoffending partners in the social order. The young attackers are part of this order, indistinguishable from it—until, that is, they emerge one day, inventively armed and intent on carrying out some private fantasy. When the details of such crimes become known, the killers' motives, if they can be determined at all, usually turn out to be trivial grudges, hardly worth the outrageous crime or the lifetime of punishment to be endured. What is particularly unhinging about these killings is that they are planned without obvious motivation and are marked by the coldest kind of contempt for the victims.

The Zantops' murders are not unique in Vermont's recent history. A cluster of assaults, less publicized but similar in nature, have disrupted the state's tranquillity in recent years.

In November of 1997 Dwayne Bernier, the owner of a tattoo shop on a rural highway outside Rutland, Vermont, was found stabbed to death in his shop. Two local teenagers, one eighteen and the other sixteen at the time, were eventually convicted of the killing. The older boy, needing money to make his car payments, had recruited the sixteen-year-old to help him, and had invited a fourteen-year-old to come along and watch. The three drove to the tattoo shop, where Bernier, who was expecting to sell them a marijuana pipe, let them in after closing hours. The two assailants attacked him, one of them using a heavy, curved, and extremely sharp combat knife known as a Gurkha. The knife's blade was driven into each of Bernier's eyes. One of the thrusts penetrated to the back of his skull.

Early one evening in late May of 1999 Jane Hubbard, a fifty-nine-year-old British expatriate who over the years had supervised a succession of foster children in her rural cottage, at the edge of Vermont's Northeast Kingdom, lay dozing in her living room. Hubbard, a mild woman whose other pursuits included selling books and raising horses, was awakened by two of her charges, boys who were fifteen and fourteen. They called her into the kitchen and demanded her car keys. When she refused, one of them told her to take off her glasses—so that he wouldn't cut his hand when he punched her, she recalled his saying. He struck her three times while the other boy held her down. "I've never seen anything swell that fast," the puncher idly remarked to his accomplice. "Just like in the movies."

One of the boys slashed her in the shoulder with a kitchen knife. Then the two began calmly to debate the most efficient way of finishing her off. If they killed her at the house, they agreed, the body would be found too quickly.

The older boy suddenly became very agitated and threw a chair at her. Then they hustled Hubbard out to her blue Saturn, and shoved her into the passenger seat. One boy drove while the other held the knife to her throat. About five miles from the house the boys decided that they wouldn't kill her after all—they "chickened out," they later told the police. Instead they pushed her out of the car and into a ditch. Bleeding, she waited in a field by the ditch until she felt it was safe to seek help. Eventually she was picked up by a passing driver.

After dumping Hubbard, the boys drove to a relative's house, where they gathered some shotguns, a rifle, and ammunition. They planned to sell the guns for pocket money and then visit some friends in New York. They were arrested after midnight, near the Vermont-New York border, when a traffic accident forced their car to a halt. A trooper at the scene had peered inside the Saturn and seen the unconcealed bundle of guns, the knife, and blood on the passenger seat. The older boy explained his motive to the trooper later. "If you had to listen to that British voice," he said with a laugh, "you'd want to kill her too."

A friend of Jane Hubbard's told the police that she was familiar with the young perpetrators. "These were kids who wore their bicycle helmets," she said. The woman remarked on how gentle the boys had seemed with the animals at a local stable.

A similar assault, in February of 2000, was far worse. Early on a weekday morning a West Burke man named Randy Beer was taking a shower when he heard something go pop in another room in his house. Drying himself off and investigating, Beer found his seventeen-year-old foster son holding Beer's .22-caliber rifle. Then Beer saw the body of his wife, Victoria, forty-four, a popular seventh-grade teacher in the local school system. The boy had killed her with a single shot to the head. Victoria's fourteen-year-old stepdaughter—Beer's daughter—had been looking on.

The boy locked Beer in the basement and stole some cash, and the two teenagers fled in the victim's red Isuzu Rodeo. Beer managed to free himself two hours later and called the police. A state trooper spotted the Isuzu cruising a street in the nearby town of St. Johnsbury and flipped on his flashing lights. After a high-speed chase the boy pulled over. Later that day the girl allegedly confessed to a state police detective that she and the boy had worked out three separate plans to kill both parents. The reason, she explained, was that they didn't like Victoria.

A fourth episode touched the circles of my family's life. Shortly before Christmas in 1999 my wife and I drove from our home to a small town in western Maine, where our oldest son was enrolled in a prep academy. We sat with a crowd of other parents in the school auditorium and watched our son play his guitar in a holiday music program—a program that also included, among other elements, a choir.

After the concert the students dispersed for the holidays. We and our son drove back to Vermont, as did Bill Stanard and his seventeen-year-old son, Laird, one of the boys who had sung in the choir. The Stanards lived in a small town in southeastern Vermont. A few days later we learned that the following night Laird had shot his mother, Paula, to death in the kitchen with a shotgun.

According to a teacher who befriended him in jail, Laird later indicated that he had thought about the killing in advance. His mindset had less to do with hatred than with a mixture of anxiety and frustration. He had developed a fantasy reinforced by the film American Beauty, which he had watched several times. The movie offered a vision of murder as a gift of transcendence, because a character who is killed—an adolescent's tormented father—does not seem really to die: he narrates the film, commenting on the plot. He is serene, still sensate, hardly inconvenienced by his own demise. The teacher later observed that the only flaw in Laird's enactment of the plan—the only production hitch in his personal movie—was that after sending his mother into the eternity of voice-over, he had failed in an effort to kill his father. And yet, in the state of half-real, half-imaginary perception he'd worked himself into (a state common to more adolescents than their elders may suspect), it didn't matter. Laird's act of murdering his mother seemed to him just another movie scenario. "I love my mother," he insisted to his teacher. "If you saw what I did, you'd understand."

Bewildered ChildrenBewildered, depraved children, behind bars, are a great deal more commonplace in Vermont than national surveys and tourist brochures would have us believe. The plight of children—or, as certain adult Vermonters demonstrably prefer to look at it, the inconvenience of children, the downright menace of children—has become a dominant theme of life in the state in the years I have lived there. Although Vermont enjoys one of the lowest crime rates in the nation, and although the region is recovering from a harsh economic slump that hit at the beginning of the 1990s, signs persist that the connections between children and their host culture here are unraveling. Kids are in trouble even here in Vermont. The reasons elude easy explanation.

That an explosion in serious juvenile crime has occurred in Vermont is undeniable. Data gathered by the Vermont Department of Corrections in 1999 revealed that the number of jail inmates aged sixteen to twenty-one had jumped by more than 77 percent in three years. (By that time overcrowding had obliged Vermont to start shipping some of its prisoners off to Virginia and other states.) Vermont's Department of Corrections reported that it supervised or housed one in ten Vermont males of high school age. The annual DOC budget more than doubled during the 1990s, from $27 million to more than $70 million. A report by the northern New England consortium Justiceworks, released in 2000, asserted that "while overall crime rates are down in northern New England, a greater proportion of those crimes are being committed by children under the age of 18."

Panic-inducing mischief has also become a fact of adolescent daily life. In the year following the April 1999 Columbine massacre Vermont experienced an epidemic of anonymous bomb threats that caused school evacuations up and down the state. The threats grew so routine that the administration at one sizable high school in the southeastern part of the state installed a voice message for people who telephoned the school during a crisis: "We're sorry, but we cannot take your call now, due to an evacuation." Police guards, uniformed and armed, became fixtures in many of Vermont's public schools. In February of last year a seventeen-year-old named Bradley Bell, from Milton, Vermont, was arrested for manufacturing pipe bombs in his house. County prosecutors said their information indicated that Bell might have intended to plant the bombs at the high school. As of this writing, this case has not come to trial.

The number of dropouts in the state's public schools showed an increase of nearly 50 percent in the 1990s—from 1,060 in 1992 to 1,585 in 1998. Meanwhile, admissions to Corrections Education, a program run for adolescent offenders by the state's Department of Corrections, grew in 1998 from 160 in June to 220 in November. The number of young people without a high school diploma in the "corrections" population increased from 87 percent to 93 percent from 1987 to 1998.

Heroin addiction was virtually unknown among Vermont children as recently as three years ago, but by 2000 heroin abuse was an established crisis throughout the state, and by early last year the volume of confiscated heroin had increased fourfold since 1999. Young addicts turned up in nearly every town of substantial size. Newspapers began reporting deaths resulting from overdose. Last September the police in Winooski, which borders Burlington, arrested an eighteen-year-old and charged him with dealing heroin from an apartment next door to a school. The police said they had found 397 bags of the narcotic in his possession.

"Heroin is almost as easy to get in Burlington as a gallon of maple syrup," The Burlington Free Press reported in February of 2001. The same edition of the paper chronicled a horrifying heroin-related story about a sixteen-year-old Burlington girl, Christal Jones, who had been found murdered a month earlier in a Bronx apartment. A runaway and sometime ward of the state's social-services agencies, Christal had developed a heroin habit that led her into prostitution. She was one of several young Vermont women drawn into the prostitution ring of a Burlington hustler with connections in New York.

An Adolescent Army of OccupationOn our arrival in Vermont, my wife and I settled in Middlebury, in the Champlain Valley, near the state's western border. We took up teaching careers at Middlebury College, from which we emerged after a few years into more congenial pursuits. We watched our boys and our friends' children flourish in a sunlit world of safe neighborhoods and committed schoolteachers. It was a world in which guests at a dinner were likely to haul out guitars after dessert was cleared away, in which the baseball coach doubled as the Baptist minister and store saleswomen remembered kids' shoe sizes better than their parents did. Both our sons quickly learned to say "The usual" at the breakfast diner across the street from the green. They swam for the town team in the summer, skied the Green Mountains in the winter, and cycled the local streets and roads with a freedom unimaginable in a city or a suburb. One day, as we strolled past a storefront with a fresh coat of bright-green paint, my older son, then about eight, actually groused, "Pretty soon they'll have this town so changed you won't even recognize it!" We hadn't yet sensed the deeper changes taking place.

On a winter day in 1994, leafing through a pile of student essays that mostly dealt, as usual, with the exalted anorectic-alcoholic reveries of the corporate ruling class's daughters and sons, I found a paper on a different topic, turned in by a working-class student from Vermont. She had written about an incident in her home town, Rutland, some thirty miles to the south: a night-time street battle, involving beer bottles and baseball bats, between local kids and a coterie of newcomers distinguished by their red berets, baggy clothes, and Hispanic surnames.

This was how I discovered that urban youth gangs had arrived in Vermont. Soon everyone knew. Trickling into the state from played-out industrial cities in Connecticut and Massachusetts, on the run from rivals and sensing a virgin market for their contraband, members of gangs with names like Los Solidos, La Familia, and Latin Kings had rented houses in towns throughout the state, and had begun recruiting locally. The violent resistance by the teens in Rutland, it soon grew clear, had been an exception: a lot of Vermont boys and girls seemed delighted by the newcomers. Soon everyone was reading about town kids who joined with the young crime lords to open up new markets for marijuana, cocaine, and, as became clear a few years later, heroin. Dozens of adolescents left their working-class families to get "beaten in" to gang membership. They learned new skills: extortion in the public schools, for instance, and running a drug-dealing route—or, in the case of girls, providing lodging, parents' credit cards, and, occasionally, sex for the visitors. Arrested and incarcerated alongside their new mentors, the local teens helped to convert the state's jails, which absorbed a 600 percent increase in gang-member inmates from 1995 to 1996, into thriving gang recruitment centers.

Nothing since the countercultural invasion of the 1960s had produced such a shock within the state. Police departments formed gang task forces and hustled their personnel off to urban seminars on gang menace and management. The public-safety commissioner warned that the state would be unable to combat its growing gang problem without federal assistance.

The psychological border separating Vermont from everywhere else, it seemed, had crumbled, and with it the old pieties about the state as a haven for the rearing of children. Vermont was just one more piece of American turf claimed by an adolescent army of occupation: the 25,000 distinct gangs, comprising more than 650,000 members, that were operating throughout the country. According to the National Youth Gang Center, every American state reported gang problems in the 1990s, as did half of all cities and towns with populations under 25,000.

In Vermont new task forces eventually crushed the gangs (or drove them underground) with paramilitary efficiency: surveillance, infiltration by informants, physically rough interrogations, and night-time phone calls to the parents of suspected gang members. The scare headlines gradually disappeared, and everyone pretty much went back to behaving as if nothing big had happened—everyone except the children. Few Vermonters were inclined to ask a question that their state's communal ethos should have rendered inescapable: What had made the gangs so attractive to their children in the first place? Few paid attention to a common explanation offered by local kids, on the rare occasions when they were asked: they saw the gangs as a replacement for something missing in their lives—namely, a community that satisfied their longings for worth-proving ritual, meaningful action in the service of a cause, and psychological intimacy.

Some months after all the excitement had ebbed, I mentioned my bewilderment at the gangs' successful penetration of Vermont to Chris Frappier, an investigator with the state public defender's office. Frappier is a cheerful fellow with a beard and an earring who himself grew up poor in a small Vermont town. "There's good within the gangs," he said with a shrug, as if stating the obvious. "They take care of each other. There's bad boys, there's less bad boys—there's a continuum. They come up here to Vermont to chill out, or because there's not as many cops. And who's waiting for them? Our kids. Our kids, the MTV generation. To them, these guys look like TV stars! So our kids, our children, who feel lost, disenfranchised—they join up! And why not? They don't have enough support services in this state. I mean, look at the communities. Look at the communities in this state that wage war on their youth. You've got Vergennes, kicking kids out of the park. You've got Woodstock banning skateboarding." The detective grew more heated as he spoke. "What I'm seeing in recent years is the total and complete alienation of youth," he said. "And it is not coming from them; it's coming from the adults who aren't bothering to reach out to them. And it is terrifying. Straight hedonistic drugs and music and misogynism. I walk Church Street in Burlington and I see kids that are walking dead and know it. And that is the biggest change of my lifetime in Vermont."

The Language of ApocalypseTheo Padnos is a slightly clerkish-looking man of thirty-four, small and pale, whose horn-rimmed glasses and mop of curly, uncombed hair make it easy not to notice the wiry mountain-biker's sinews in his arms and legs. It's easy not to notice Padnos's presence at all, in fact, which is the way he likes it, especially when he is doing what he does best: paying acute attention.

Padnos is a former bicycle-shop salesman and telemarketer who often has had trouble finding a suitable job. He has a Ph.D. in comparative literature, which he earned in June of 2000 from the University of Massachusetts at Amherst, but this has not helped him much in his quest for employment. He can be impressive in ticking off the list of university teaching jobs throughout the United States and Canada for which he has applied without success.

A couple of years ago, desperate for an income and hungry to teach something to somebody, Padnos applied for a part-time job teaching literature to adolescents in the Community High School of Vermont, a program administered by the state's Department of Corrections. Its pupils are inmates in the prison system. Padnos was assigned to the regional correctional facility in Woodstock, on the state's southeastern border—just across the Connecticut River from Hanover. The facility, built in 1935 and scheduled for abandonment by the corrections system this spring, is wedged between an auto-parts outlet and a convenience store on the unfashionable eastern edge of a fashionable town. Its exterior, red brick and whitewashed wooden trim, evokes a schoolhouse. Its interior, in the words of the state's commissioner of corrections, evokes "a James Cagney movie": it's an antiquated warren of locked metal doors, Plexiglas monitoring windows, and iron grillwork, with gray paint and a prevailing odor—diluted by disinfectant—of burned meat from the cafeteria. Its capacity is seventy-five inmates. Its superintendent says he "hates" to see the population rise above eighty. About half are convicted adult felons, the other half kids awaiting trial. The two populations mix indiscriminately. Padnos taught in a basement classroom there for thirteen months.

Teachers in the Vermont correctional system are offered several layers of protection from their charges: surveillance cameras in the classrooms, walkie-talkies they can clip to their belts, classroom doors left open to allow fast entry by guards in case of trouble. Most teachers accept the full inventory, but Padnos rejected everything. His motives had less to do with bravado than with practical concerns, he told me when we spoke recently. "I got rid of the camera, I let the inmates close and lock the door, and I even allowed them to expel the jail snitches if they wanted to," he said. "I allowed this because, as a teacher in the liberal arts, I try to humanize my students. I was interested in staging an intimate, private encounter with literature, and I thought that a measure of privacy and separation from the inhuman jail would help."

Padnos found himself inside a compacted sampling of the sub-population from which the deliverers of sudden violence have lately been emerging: the young, the male, the white, the angry, the ignored, the overstimulated, the intelligent if not well educated. The dangerous dreamers. Most of his charges were in for mid-level crimes such as drug use, assault, and robbery. If they had lacked for attentive adult mentors in the outside world, they now lived at close quarters with plenty of them: adult rapists, gang members, and murderers. Although largely poor and from rural communities, these young inmates represented a range of social classes in Vermont, a rural state that is laced with pockets of poverty. With one eminent exception, they had not yet broken through to the level of crime that stops the larger world in its tracks. But as Padnos quickly came to perceive, such an achievement preoccupied most of them. It formed their imaginative agendas. "They're fascinated by the details of their crimes," he told me, "and by violence in general. Violent crime is the one topic to which they can devote sustained concentration. When my classes touched on this subject, as almost all jail classes eventually do, they became a kind of seminar. Everyone was well informed, everyone felt entitled to participate, and everyone was prepared to teach something. When I asked the students how often they read the police files they carried with them to class—all the witness statements, the blood and ballistics analyses the prosecution had turned over to the defense—they would say, 'All the time. Over and over. And over.'"

Arranging their future crimes was the long-term extracurricular project that kept them busy, Padnos learned, and they received constant guidance and reinforcement from the hardened jailbirds in their midst. "The parole and probation people may have thought they had these kids in their radar," he told me, "but the kids were already thinking way beyond rehabilitation. They weren't talking about getting jobs, going back to school, anything like that. It was through crime that they intended to reintroduce themselves to the world."

The facility's superintendent, William R. Anderson, backs up Padnos's observations. He told me that although instances of violent crime in Vermont had not increased in recent years, the severity of violence had intensified "significantly." "I'm seeing something in young people coming into jail today I've never seen before," he said. "The seventeen-, eighteen-, nineteen-year-old kids I see, they don't care about anything, including themselves. They have absolutely no respect for any kind of authority. They have no direction in their lives whatsoever. They're content to come back to jail time after time after time."

Into this context Padnos brought an ambitious syllabus: James Baldwin, Edgar Allan Poe, Cormac McCarthy, Flannery O'Connor, Mark Twain. "I wanted to teach them to imagine themselves in the situations of others in similar predicaments," he said. "I wanted to show them that they are not the isolatos they take themselves for. What they are going through is not unique to them; these struggles have been experienced and written about all through history."

As he thinks back on it now, Padnos concedes that aside from a few scattered, near accidental moments when the literature, the students, and his instruction coalesced, his course was a failure. "They were too far gone by the time they arrived in prison," he said. "This was true of the middle-class, public high school, bomb-threatening kids; it was even true of the well-educated preppie kids. And their experience in prison pushed most of them even further away from any hope for involvement with a civil, productive life. Just once in a while I saw it happen: they'd relate to something I'd brought them to read or talk about, and for a few minutes they'd be transformed into children—wide-eyed, frightened, hopelessly lost. Then a jailer would give a knock, tell 'em time was up, and that moment would be over."

But something else began to happen in those jagged sessions, a transformation that Padnos had not anticipated. The jailed kids, gradually and roughly, came to accept him as one of themselves. The key to the process, he believes, was his jettisoning of the classroom safeguards. None of the other teachers had dared to let go of those, and their refusal amounted to a statement of irreducible fear, disgust, and membership in the target world. Padnos's students made him prove that he meant the gesture: they sized him up, shouted him down, mocked his questions, cursed and tried to intimidate him for a while. They demanded to know why anybody like him would spend time in jail if he didn't have to.

Padnos became a player under inmates' rules. He believes that his youthfulness helped, and also his unconcealed affinity for the outlaw point of view. "I have an attraction to people who don't mind causing offense," he told me. "People who are disappointments to themselves, and whose families don't know how to account for them." Whatever the reasons, when the layers of distrust had burned away, Padnos found himself privy to, and taking part in, conversations of the sort that usually unspool only among the dispossessed, and only in those moments when they feel they are free from interlopers, secure with their own kind.

What Padnos began hearing in these conversations, he says, was the language of apocalypse. "The goal for the bright ones is to truly mesmerize the middle class with violence," he told me. "They've been transfixed by disaster themselves—in their families, at the movies, in the company of their mentors in crime. They've come to feel that there's nothing out there for them. And so they know exactly the effect they're looking for. They keep up with the news. They read about their deeds in the papers. They've been ignored all their lives, and they're pleased to see that the public is finally giving them some of the attention they're due. The papers always describe their crimes as 'senseless,' and 'meaningless,' and 'unmotivated,' and these kids themselves always come off as 'cold' and 'distant' to the reporters. The details of their crimes are always covered with the tightest possible focus, as if meaning might be found there. The result is just what they'd been hoping for: terrifying, mesmerizing violence, and no context."

Padnos, who is writing a book about his experiences, hardly endorses this violence. His classroom goal, in fact, had been to transmute the violent impulse into a quest for self-understanding through the medium of literature. He had hoped, in the best postgraduate fashion, that through a guided reading of "The Cask of Amontillado," or Cities of the Plain, he might awaken his young charges to the healing awareness that their torments are part of the human condition.

Instead Padnos found himself becoming a student in a different kind of seminar. Listening to the boys in his classroom, he began to comprehend that the deeds they had committed, and the language with which they described future deeds, amounted to a text that American society has so far stubbornly resisted decoding. The message Padnos found embedded in this text is that in a world otherwise stripped of meaning and self-identity, adolescents can come to understand violence itself as a morally grounded gesture, a kind of purifying attempt to intervene against the nothingness.

"They're a community of believers, in a way," he told me. "They come from all kinds of backgrounds. But what unites them are these apocalyptic suspicions that they have. They think and act as though it's an extremely late hour in the day, and nothing much matters anymore. A lot of them are suicidal. Most of them see themselves as frustrated travelers. Solitary wayfarers. They've done things that have broken them off from their past and set off on the open road. Eventually they got arrested. This may be hard for some people to swallow, I guess, but they talk about their crimes almost as if they were acts of faith. Maybe these kids themselves wouldn't use those words. But the things they've done, on some level, strike me as almost ecstatic attempts to vault over the shabby facts of their everyday lives. They haven't read much. But some of them, the more down-and-out ones especially, read the Book of Revelation a lot."

These kids also watch a lot of movies and TV. No surprise there. But it's what they extract from these sources that engrosses Padnos. "They're drawn to the myths built into these violent movies, not just the violence itself," he said. "Prison life, especially for kids—maybe life in general for kids—is soaked in myths about outlaws, self-reliance. People traveling a rough landscape that is their true home. People who mete out justice to anyone who impinges on their native liberties. Post-apocalyptic heroes, just like they want to be—violent, suicidal, the sort of people who are preparing themselves for what happens after everything ends.

"These kids half believe that their destination is the same as these screen heroes'. That it's something like the roadside shantytown in Mad Max. They devour Taxi Driver, especially the Travis Bickle speech in which he prophesies a great rain and promises that it will wash the streets of their scum. They relate to the themes in Terminator II and The Postman. And Reservoir Dogs, and Wild Things. These were practically our class canon." Padnos thought for a minute. "I admire my students," he said. "Sometimes I wish that I had the courage they have. I just think of them as passionate, thoughtful, lucid, well-informed, literate, morally sophisticated, homicidal all-American kids."

Laird's StoryInto Padnos's classroom one crisp January day in 2000, "full of prep-school chumminess," as Padnos remembers it, walked the plump and fair-skinned seventeen-year-old Laird Stanard, who a few weeks earlier had murdered his mother with a shotgun. "The story had been in every newspaper, and on every local news broadcast in Vermont," Padnos said. "All the prisoners knew about it. So here came Laird, circulating in the jail's general population, available to anyone who felt like eviscerating a kid who had just killed his mother."

Padnos had a ringside seat, as it were, for the boy's introduction to jail life—to the rest of his life. "They were waiting for him," he recalled. "I hadn't figured out why eighteen students were suddenly keen on coming to my class. They filled every chair in the room. As soon as he walked through the door they were yelling, 'All right! Here he is! The man!' I remember how addled Laird was, how indignant. His whole attitude was 'Me? Shoot my mother? Hey, I'm as distraught as anyone! What the fuck are you talking about?'"

Padnos found himself helpless to prevent the cruelly comic initiation that followed. The class kingpin, a fleshy character whom Padnos refers to as Slash, took charge. "She's your mother, for God's sake, kid!" he yelled at Laird. "I just don't get that. I mean, she's your own goddamn mother! What are you going to do? 'Hi, Mom—KA-BOOM?' I mean, come on! KA-BOOM!" Padnos remembers the raucous laughter that spread through the classroom. "KA-POW! BAM! Take that, bitch!" More laughter. Padnos ruefully recalls laughing a bit himself. Other kids took up the patter: "Hey, Mom! Present for ya. KA-BOOM!" "Wasn't she your own mother, for Christ's sakes?"

Through it all Laird sat in shocked silence, his jaw locked. Still not clear in his own mind about what he had done, he had apparently steeled himself to endure whatever this new environment offered. He had come into the room cheerfully prepared, with his prep-school notes, to discuss Edgar Allan Poe. In the days that followed, Padnos watched Laird try to make sense of where he was. The boy offered up his credentials to the new people in his life—almost, it struck Padnos, as a tourist might in a place far from home. The other prisoners ignored him.

Padnos did not. He forged a friendship with Laird, who was desperately receptive. "We were similar," Padnos said. "We knew the same types of people, our parents were similar people, we're both prep-school kids. We were both overwhelmed by the thugs in this jail, and we both wanted to establish a civilized island in that uncivil world." Over the course of several intimate conversations Padnos saw Laird's denial slowly dissolve. He began to hear the authentic voice of an unformed, unfinished adolescent trying to explain why he had done what he had done.

Laird's story was not the sort that is usually told in attempts to reconstruct a motive after vaguely similar adolescent killings. There were no easy formulations here about the effects of bullies, or drugs, or a predisposition to violence. His account was at once more disjointed and far more specific than that. Padnos recalls it as the story of a confused boy whose parents were thwarting him. The Stanard family lived in a renovated farmhouse on several acres of land off a rural thoroughfare called Blood Hill Road. His parents raised sheep and horses. Laird's father, Bill, had taught in both public and private high schools. He had been a naval officer in Vietnam. He had given his son gun training. Laird's mother, Paula, the daughter of a wealthy family, had been the boy's strongest ally. Laird recounted fond memories of the two of them smoking cigarettes together and talking about life.

According to Padnos, Laird did not want to go home to West Windsor with his father the night of the holiday music program at his school. He wanted to visit a girl he liked in Maine. But his father insisted that they return to the house on Blood Hill Road.

On the following night Laird left the house without notifying his parents, taking a shotgun and a family car. He went to a rural nightclub in the area, called Destiny, where he sat smoking cigarettes and watching people dance. When he returned home, at one o'clock, Paula Stanard was indignantly waiting for him. She and Laird quarreled briefly. Then Laird leveled the shotgun, which he had concealed behind him, and killed her with one shot. When his father came stumbling down the stairs at the sound of the report, Laird tried to complete the double murder he had contemplated, but in his panic he misfired. He lurched out the door to the car and spun down the driveway, striking a snowbank, the mailbox, and a tree. He drove six miles to a party at a ski resort. At the party he pressed a wild story on several people: he had picked up a hitchhiker in the middle of the night, and the hitchhiker had forced his way into the Stanard house and shot his mother. "His plan was a movie plan," Padnos told me. "He thought he would live with his girlfriend, off on the lam someplace, with his dad's shotgun and his mother's credit card to help them get around." One of the people who listened to Laird's story called the police. It took the local police four days to arrive at the truth.

In the weeks and months following Laird's arrival, Padnos watched as Laird developed a kind of sangfroid in his new role as a criminal. "He started giving me reports," Padnos said, "on what it was like to live in a world where he was at the center of attention. He claimed to have movie projects in the works, and he tended to know people who appeared in the news personally. Other criminals."

Who Knows?Last summer Laird Stanard accepted a deal: in return for a plea of guilty to charges of murdering his mother and attempting to murder his father, he was given sentences of twenty-five years to life and, concurrently, twenty years to life. Theo Padnos testified at the sentencing hearing and wrote to me about it.

What a strange scene it was. Laird's dad ... [and his] mom's family [were] there, as were a bunch of neighbors and former teachers and reporters. The funny thing was that during the intermissions when the spectators ambled around outside the courtroom, the whole thing felt like a happy waspy cocktail party. We all knew a bit about one another—"Oh, you're Theo," people said to me, and smiled ...

Laird was in a good mood too. He was the center of attention. When I testified, I kept trying to get up and leave the witness box before I was really supposed to go, and this was amusing to everyone in the courtroom but especially amusing to Laird. (I didn't wait for the DA or the judge to ask their questions.) The judge laughed, I laughed, everyone smiled. When the DA asked me if Laird fully understood "the enormity" of what he's done, I wanted to say that yes, I think he understands that enormity more than the rest of us, because he has nightmares all the time, because he sometimes sleeps twenty hours a day, because he sometimes sits in class absolutely terrified by what we're reading. And the rest of us are amusing ourselves at a cocktail party. But of course I wasn't thinking like that. Instead I just said that I thought that the consequences of the crime couldn't be fully appreciated yet by him but that he was making progress.

The other funny thing was that the defense psychiatrist testified at length in the most somber, lugubrious voice you can imagine about Laird's "borderline personality." Laird had suicidal ideation, he had ADHD and ADD, he had a history of unstable relationships, chronic suicidality (I don't think so), marked reactivity of mood (what? he gets angry easily, I guess), he saw everything in black and white w/o grays, and on and on. This guy was also a great performer. Very solemn and full of technical language. He concluded that when L's mom yelled at him, L overreacted because of his BPD and blew her away with a shotgun. The shrink said that the borderline illness/syndrome had "the most explanatory power" of any of the diagnoses in the DSM IV, the great manual of the psychiatrists, and basically, Laird wasn't well in the head: if anything "caused" the crime, it was this. The judge weighed in later with his own diagnosis. He seemed to feel that what provoked the crime was Laird's mom who made him total up [a large number of] credit card charges by hand, when Laird had difficulty adding. This frustration/humiliation was too much for someone with the borderline personality problem, so he shot her. I don't know what the judge said to himself afterwards, but the shrink, chatting with my fellow jail worker and me on the sidewalk outside the courthouse, said, "I don't have any idea what the reason is, you know? Who knows?"

They Are UsTo most people, the notion that an apocalyptic nihilism is taking root in this nation's children will seem alarmist. Much of the evidence can be seen as variations on age-old complaints, familiar generational impasses, and inevitable exceptions to a reassuring general rule: that tranquillity still reigns. After all, are not most kids well-adjusted? Do not the vast majority of them pass through adolescence without episodes of addiction, pregnancy, criminal behavior, self-destruction? Have grown-ups not complained since time immemorial about "kids these days"? And have not kids forever groused that the adults in their lives don't understand them? Have there not always been instances of violent aggression among a few antisocial delinquents?

Parents who generalize from the apparent contentedness of their own children are indulging a dangerous fallacy. Children, like people in general, present different faces to different groups within their social universes, a state of affairs amply documented by Judith Rich Harris in her important book The Nurture Assumption (1998), which illustrated the multiple, often contradictory personas elicited variably by parents, peer groups, siblings, and prevailing societal influences. Equally treacherous is the view that the young have always been inscrutable to adults and have always complained about being misunderstood. Since the end of World War II adolescents have been chafing against an ever more impervious, unheeding social system. Their outrage has found expression, with increasing intensity, among the inchoate "juvenile delinquents" of the early postwar years, the Beats of the 1950s, the hippies and political radicals of the 1960s, the drug and gangland subcultures of more recent years. And now it's expressed by the kids who carry out school shootings and other acts of vicious and inexplicable violence. The questions we must ask ourselves today, therefore, are these: Why are so many children plotting to blow up their worlds and themselves? For each act of gratuitous violence that is actually carried out, how many unconsummated dark fantasies are transmuted into depression, resignation, or a benumbed withdrawal from participation in civic society?

What we are witnessing is clearly something new. A frightening momentum has been building, and the qualities of generational understanding and assurance that once earned America a worldwide reputation as child-centered are fading fast. And yet despite a growing awareness of this fact, the public policy that we are developing to cope with troubled kids is only exacerbating the situation. Let us leave aside considerations of withering support for public education and inadequate federal support for impoverished working mothers. Let us consider our present policy in its rawest and most adversarial form: in the state's growing arrogation of power to punish rather than to rehabilitate. This is a policy that expresses both fear of and contempt for children.

In the 1990s public figures such as John Ashcroft and William Bennett successfully campaigned to make certain that the juvenile justice system no longer "hugs the juvenile terrorist," in Ashcroft's words. As Margaret Talbot pointed out in The New York Times Magazine in September 2000, forty-five states in that decade passed new laws or enacted changes in old ones that toughened criminal justice and criminal penalties for the errant young. Fifteen states transferred to prosecutors from judges the power to choose adult prosecution in certain crimes. Twenty-eight states created statutory requirements for adult trials in some crimes of violence, theft and robbery, and drug use. In 1994 President Clinton's Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act federalized many of the states' initiatives, authorizing adult prosecution of children thirteen and over who were charged with certain serious crimes, and expanding the death penalty to cover some sixty offenses. As Talbot wrote, "The number of youths under 18 held in adult prisons, and in many cases mixed in with adult criminals, has doubled in the last 10 years or so ... to 7,400 in 1997. Of the juveniles incarcerated on any given day, one in 10 are in adult jails or prisons."

These draconian efforts seem to fly in the face of emerging scientific research demonstrating that the brains of children and adolescents are not yet fully formed—not yet equipped to make precisely the sort of emotional and rational decisions necessary to restrain impulses in certain situations that can lead to antisocial and criminal behavior. Adolescents, with directed and scrupulous supervision, can indeed change and grow emotionally and psychologically, but our public policy seems intent on denying this possibility. But if the government is in denial, the marketplace is not: with the help of exhaustive behavioral research, corporations have in recent decades spent hundreds of millions of dollars ransacking and exploiting the emotions and thought processes of adolescents and pre-adolescents. RoperASW (with its Roper Youth Report), Teenage Research Unlimited, and similar organizations, using methods derived from the behavioral sciences, advise merchandisers and advertising companies on the latest semiotics of "cool" and consumer-friendly subversion. "We understand how teens think, what they want, what they like, what they aspire to be, what excites them, and what concerns them," the Teenage Research Unlimited Web site brags. What this understanding translates into in the marketplace is hypersexuality, aggression, addiction, coldness, and irony-laced civic disaffection—the very seed-bed of apocalyptic nihilism.

The national task of recentering ourselves and our children will be enormous, and will require painful shifts in our expectations of expediency, personal gratification, and the unfettered accumulation of wealth. But the goals are necessary and anything but obscure. Children crave a sense of self-worth. That craving is answered most readily through respectful inclusion: through a reintegration of our young into the intimate circles of family and community life. We must face the fact that having ceased to exploit children as laborers, we now exploit them as consumers. We must find ways to offer them useful functions, tailored to their evolving capacities. Closely allied to this goal is an expanded definition of "education"—one that ranges far beyond debates over public and private schools and how much to spend on them to embrace an ethic of sustained mentoring that extends from community to personal relationships.

The societal shift of consciousness necessary for such a recentering is—in a pre-apocalyptic context, at least—virtually unthinkable. But America is lately learning to rethink many assumptions it once comfortably took for granted, out of terrorist promptings eerily similar to the bloody messages being delivered by certain of our young.

.....

Briefly, then, back to Vermont. The town of Chelsea, the home of Robert Tulloch and Jimmy Parker, scarcely has the look of a town that would breed teenage killers, for one simple reason—it is not such a town. Chelsea is a place that breeds human beings, whose fates are bound up in the larger forces and energies of the nation. There is no real mystery over the identities and the motivations of Tulloch and Parker, or of Laird Stanard. They are us, and they are ours.