Discourse on the Worship of Priapus, Part 1MEN, considered collectively, are at all times the same animals, employing the same organs, and endowed with the same faculties: their passions, prejudices, and conceptions, will of course be formed upon the same internal principles, although directed to various ends, and modified in various ways, by the variety of external circumstances operating upon them. Education and science may correct, restrain, and extend; but neither can annihilate or create: they may turn and embellish the currents; but can neither stop nor enlarge the springs, which, continuing to flow with a perpetual and equal tide, return to their ancient channels, when the causes that perverted them are withdrawn.

The first principles of the human mind will be more directly brought into action, in proportion to the earnestness and affection with which it contemplates its object; and passion and prejudice will acquire dominion over it, in proportion as its first principles are more directly brought into action. On all common subjects, this dominion of passion and prejudice is restrained by the evidence of sense and perception; but, when the mind is led to the contemplation of things beyond its comprehension, all such restraints vanish: reason has then nothing to oppose to the phantoms of imagination, which acquire terrors from their obscurity, and dictate uncontrolled, because unknown. Such is the case in all religious subjects, which, being beyond the reach of sense or reason, are always embraced or rejected with violence and heat. Men think they know, because they are sure they feel; and are firmly convinced, because strongly agitated. Hence proceed that haste and violence with which devout persons of all religions condemn the rites and doctrines of others, and the furious zeal and bigotry with which they maintain their own; while perhaps, if both were equally well understood, both would be found to have the same meaning, and only to differ in the modes of conveying it.

Of all the profane rites which belonged to the ancient polytheism, none were more furiously inveighed against by the zealous propagators of the Christian faith, than the obscene ceremonies performed in the worship of Priapus; which appeared not only contrary to the gravity and sanctity of religion, but subversive of the first principles of decency and good order in society. Even the form itself, under which the god was represented, appeared to them a mockery of all piety and devotion, and more fit to be placed in a brothel than a temple. But the forms and ceremonials of a religion are not always to be understood in their direct and obvious sense; but are to be considered as symbolical representations of some hidden meaning, which may be extremely wise and just, though the symbols themselves, to those who know not their true signification, may appear in the highest degree absurd and extravagant. It has often happened, that avarice and superstition have continued these symbolical representations for ages after their original meaning has been lost and forgotten; when they must of course appear nonsensical and ridiculous, if not impious and extravagant.

Such is the case with the rite now under consideration, than which nothing can be more monstrous and indecent, if considered in its plain and obvious meaning, or as a part of the Christian worship; but which will be found to be a very natural symbol of a very natural and philosophical system of religion, if considered according to its original use and intention.

What this was, I shall endeavour in the following sheets to explain as concisely and clearly as possible. Those who wish to know how generally the symbol, and the religion which it represented, once prevailed, will consult the great and elaborate work of Mr. D'Hancarville, who, with infinite learning and ingenuity, has traced its progress over the whole earth. My endeavour will be merely to show, from what original principles in the human mind it was first adopted, and how it was connected with the ancient theology: matters of very curious inquiry, which will serve, better perhaps than any others, to illustrate that truth, which ought to be present in every man's mind when be judges of the actions of others, that in morals, as well as physics, there is no effect without an adequate cause. If in doing this, I frequently find it necessary to differ in opinion with the learned author above-mentioned, it will be always with the utmost deference and respect; as it is to him that we are indebted for the only reasonable method of explaining the emblematical works of the ancient artists.

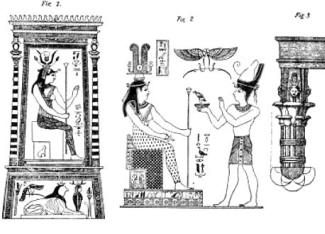

Whatever the Greeks and Egyptians meant by the symbol in question, it was certainly nothing ludicrous or licentious; of which we need no other proof, than its having been carried in solemn procession at the celebration of those mysteries in which the first principles of their religion, the knowledge of the God of Nature, the First, the Supreme, the Intellectual, [1] were preserved free from the vulgar superstitions, and communicated, under the strictest oaths of secrecy, to the iniated (initiated); who were obliged to purify themselves, prior to their initiation, by abstaining from venery, and all impure food. [2] We may therefore be assured, that no impure meaning could be conveyed by this symbol; but that it represented some fundamental principle of their faith. What this was, it is difficult to obtain any direct information, on account of the secrecy under which this part of their religion was guarded. Plutarch tells us, that the Egyptians represented Osiris with the organ of veneration erect, to show his generative and prolific power: he also tells us, that Osiris was the same Diety as the Bacchus of the Greek Mythology; who was also the same as the first begotten Love (πρωτογονος) of Orpheus and Hesiod. [3] This deity is celebrated by the ancient poets as the creator of all things, the father of gods and men; [4] and it appears, by the passage above referred to, that the organ of veneration was the symbol of his great characteristic attribute. This is perfectly consistent with the general practice of the Greek artists, who (as will be made appear hereafter) uniformly represented the attributes of the deity by the corresponding properties observed in the objects of sight. They thus personified the epithets and titles applied to him in the hymns and litanies, and conveyed their ideas of him by forms, only intelligible to the initiated, instead of sounds, which were intelligible to all. The organ of generation represented the generative or creative attribute, and in the language of painting and sculpture, signified the same as the epithet παλλενετωζ, in the Orphic litanies.

This interpretation will perhaps surprise those who have not been accustomed to divest their minds of the prejudices of education and fashion; but I doubt not, but it will appear just and reasonable to those who consider manners and customs as relative to the natural causes which produced them, rather than to the artificial opinions and prejudices of any particular age or country. There is naturally no impurity or licentiousness in the moderate and regular gratification of any natural appetite; the turpitude consisting wholly in the excess or perversion. Neither are organs of one species of enjoyment naturally to be considered as subjects of shame and concealment more than those of another; every refinement of modern manners on this head being derived from acquired habit, not from nature: habit, indeed, long established; for it seems to have been as general in Homer's days as at present; but which certainly did not exist when the mystic symbols of the ancient worship were first adopted. As these symbols were intended to express abstract ideas by objects of sight, the contrivers of them naturally selected those objects whose characteristic properties seemed to have the greatest analogy with the Divine attributes which they wished to represent. In an age, therefore, when no prejudices of artificial decency existed, what more just and natural image could they find, by which to express their idea of the beneficent power of the great Creator, than that organ which endowed them with the power of procreation, and made them partakers, not only of the felicity of the Deity, but of his great characteristic attribute, that of multiplying his own image, communicating his blessings, and extending them to generations yet unborn?

"Sometimes this generative attribute is represented by the symbol of the goat, supposed to be the most salacious of animals, and therefore adopted upon the same principles as the bull and the serpent."

-- A Discourse on the Worship of Priapus: And Its Connection with the Mystic Theology of the Ancients, by Richard Payne Knight

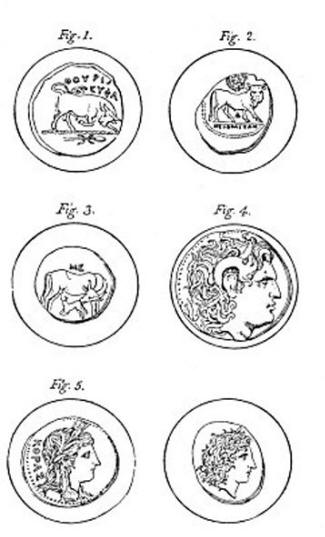

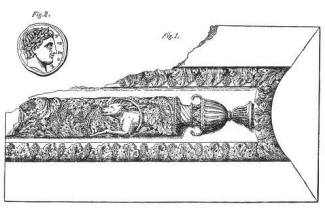

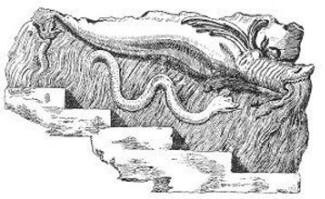

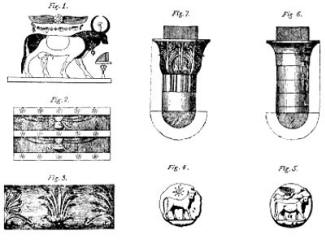

In the ancient theology of Greece, preserved in the Orphic Fragments, this Deity, the Ερως πρωτογονος, or first-begotten Love, is said to have been produced, together with Æther, by Time, or Eternity (Κρονος), and Necessity (Αναγχη), operating upon inert matter (Χαος). He is described as eternally begetting (αειγνητης); the Father of Night, called in later times, the lucid or splendid, (φανης), because he first appeared in splendour; of a double nature, (διφυης), as possessing the general power of creation and generation, both active and passive, both male and female. [5] Light is his necessary and primary attribute, co-eternal with himself, and with him brought forth from inert matter by necessity. Hence the purity and sanctity always attributed to light by the Greeks. [6] He is called the Father of Night, because by attracting the light to himself, and becoming the fountain which distributed it to the world, he produced night, which is called eternally-begotten, because it had eternally existed, although mixed and lost in the general mass. He is said to pervade the world with the motion of his wings, bringing pure light; and thence to be called the splendid, the ruling Priapus, and Self-illumined (αντανγης [7]). It is to be observed that the word Πριηπος, afterwards the name of a subordinate deity, is here used as a title relating to one of his attributes; the reasons for which I shall endeavour to explain hereafter. Wings are figuratively attributed to him as being the emblems of swiftness and incubation; by the first of which he pervaded matter, and by the second fructified the egg of Chaos. The egg was carried in procession at the celebration of the mysteries, because, as Plutarch it was the material of generation (νλη της γενεσεως [8]) containing the seeds and germs of life and motion, without being actually possessed of either. For this reason, it was a very proper symbol of Chaos, containing the seeds and materials of all things, which, however, were barren and useless, until the Creator fructified them by the incubation of his vital spirit, and released them from the restraints of inert matter, by the efforts of his divine strength. The incubation of the vital spirit is represented on the colonial medals of Tyre, by a serpent wreathed around an egg; [9] for the serpent, having the power of casting his skin, and apparently renewing his youth, became the symbol of life and vigour, and as such is always made an attendant on the mythological deities presiding over health. [10] It is also observed, that animals of the serpent kind retain life more pertinaciously than any others except the Polypus, which is sometimes represented upon the Greek Medals, [11] probably in its stead. I have myself seen the heart of an adder continue its vital motions for many minutes after it has been taken from the body, and even renew them, after it has been cold, upon being moistened with warm water, and touched with a stimulus.

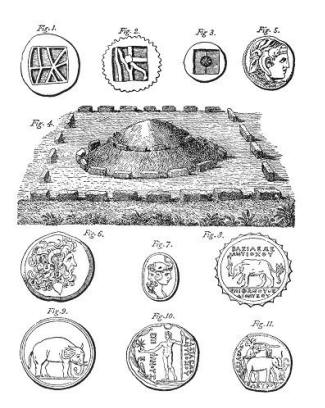

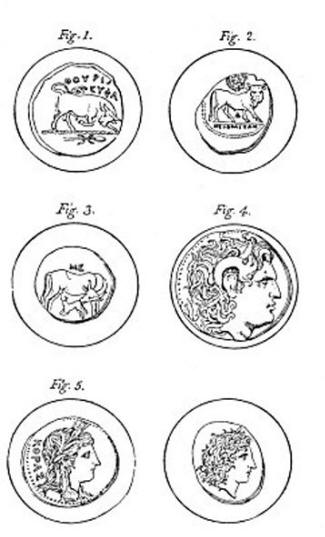

PLATE 3: ANTIQUE GEMS AND GREEK MEDALS

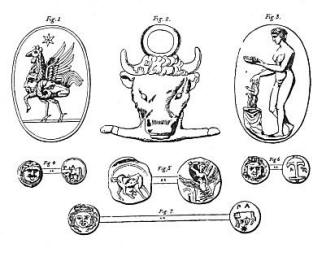

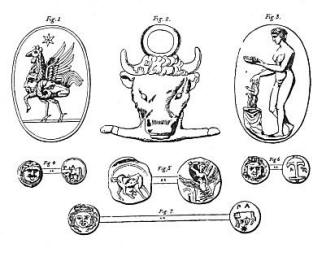

PLATE 3: ANTIQUE GEMS AND GREEK MEDALSThe Creator, delivering the fructified seeds of things from the restraints of inert matter by his divine strength, is represented on innumerable Greek medals by the Urns, or wild Bull, in the act of butting against the Egg of Chaos, and breaking it with his horns. [12] It is true, that the egg is not represented with the bull on any of those which I have seen; but Mr. D'Hancarville [13] has brought examples from other countries, where the same system prevailed, which, as well as the general analogy of the Greek theology prove that the egg must have been understood, and that the attitude of the bull could have no other meaning. I shall also have occasion hereafter to show by other examples, that it was no uncommon practice, in these mystic monuments, to make a part of a group represent the whole. It was from this horned symbol of the power of the Deity that horns were placed in the portraits of kings to show that their power was derived from Heaven, and acknowledged no earthly superior. The moderns have indeed changed the meaning of this symbol, and given it a sense of which, perhaps, it would be difficult to find the origin, though I have often wondered that it has never exercised the sagacity of those learned gentlemen who make British antiquities the subjects of their laborious inquiries. At present, it certainly does not bear any character of dignity or power; nor does it ever imply that those to whom it is attributed have been particularly favoured by the generative or creative powers. But this is a subject much too important to be discussed in a digression; I shall therefore leave it to those learned antiquarians who have done themselves so much honour, and the public so much service, by their successful inquiries into customs of the same kind. To their indefatigable industry and exquisite ingenuity I earnestly recommend it, only observing that this modern acceptation of the symbol is of considerable antiquity, for it is mentioned as proverbial in the Oneirocritics of Artemidorus; [14] and that it is not now confined to Great Britain, but prevails in most parts of Christendom, as the ancient acceptation of it did formerly in most parts of the world, even among that people from whose religion Christianity is derived; for it is a common mode of expression in the Old Testament, to say that the horns of any one shall be exalted, in order to signify that he shall be raised into power or pre-eminence; and when Moses descended from the Mount with the spirit of God still upon him, his head appeared horned. [15]

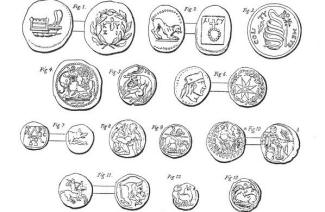

PLATE 4: MEDALS POSSESSED BY PAYNE KNIGHT

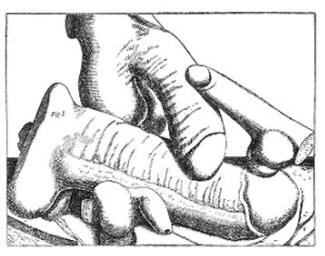

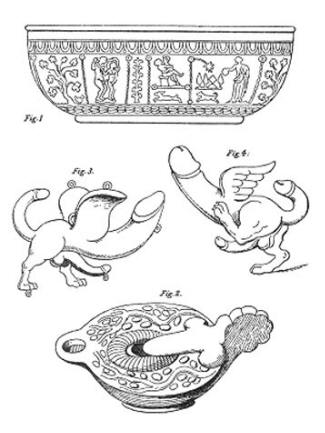

PLATE 4: MEDALS POSSESSED BY PAYNE KNIGHTTo the head of the bull was sometimes joined the organ of generation, which represented not only the strength of the Creator, but the peculiar direction of it to the most beneficial purpose, the propagation of sensitive beings. Of this there is a small bronze in the Museum of Mr. Townley, of which an engraving is given in Plate 3. Fig. 2. [16]

Sometimes this generative attribute is represented by the symbol of the goat, supposed to be the most salacious of animals, and therefore adopted upon the same principles as the bull and the serpent. [17] The choral odes, sung in honour of the generator Bacchus, were hence called τραγωδιαι, or songs of the goat; a title which is now applied to the dramatic dialogues anciently inserted in these odes, to break their uniformity. On a medal, struck in honour of Augustus, the goat terminates in the tail of a fish, to show the generative power incorporated with water. Under his feet is the globe of the earth, supposed to be fertilised by this union; and upon his back, the cornucopia, representing the result of this fertility. [18]

Mr. D'Hancarville attributes the origin of all these symbols to the ambiguity of words; the same term being employed in the primitive language to signify God and a Bull, the Universe and a Goat, Life and a Serpent. But words are only the types and symbols of ideas, and therefore must be posterior to them, in the same manner as ideas are to their objects. The words of a primitive language, being imitative of the ideas from which they sprung, and of the objects they meant to express, as far as the imperfections of the organs of speech will admit, there must necessarily be the same kind of analogy between them as between the ideas and objects themselves. It is impossible, therefore, that in such a language any ambiguity of this sort could exist, as it does in secondary languages; the words of which, being collected from various sources, and blended together without having any natural connection, become arbitrary signs of convention, instead of imitative representations of ideas. In this case it often happens, that words, similar in form, but different in meaning, have been adopted from different sources, which, being blended together, lose their little difference of form, and retain their entire difference of meaning. Hence ambiguities arise, such as those above mentioned, which could not possibly exist in an original tongue.

The Greek poets and artists frequently give the personification of a particular attribute for the Deity himself; hence he is called Τανροζοας, Τανρωπος, Τανρομορφος [19], &c., and hence the initials and monograms of the Orphic epithets applied to the Creator, are found with the bull, and other symbols, on the Greek medals [20]. It must not be imagined from hence, that the ancients supposed the Deity to exist under the form of a bull, a goat, or a serpent: on the contrary, he is always described in the Orphic theology as a general pervading Spirit, without form, or distinct locality of any kind; and appears, by a curious fragment preserved by Proclus [21], to have been no other than attraction personified. The self-created mind (νοας αυτογενεθλος) of the Eternal Father is said to have spread the heavy bond of love through all things (πασιν ενεοπειρεν δεσμον περιζριθη Ερωτος), in order that they might endure for ever. This Eternal Father is Κρονος, time or eternity, personified; and so taken for the unknown Being that fills eternity and infinity. The ancient theologists knew that we could form no positive idea of infinity, whether of power, space, or time; it being fleeting and fugitive, and eluding the understanding by a continued and boundless progression. The only notion we have of it is from the addition or division of finite things, which suggest the idea of infinite, only from a power we feel in ourselves of still multiplying and dividing without end. The Schoolmen indeed were bolder, and, by a summary mode of reasoning, in which they were very expert, proved that they had as clear and adequate an idea of infinity, as of any finite substance whatever. Infinity, said they, is that which has no bounds. This negation, being a positive assertion, must be founded on a positive idea. We have therefore a positive idea of infinity.

Scholasticism is a method of critical thought which dominated teaching by the academics (scholastics, or schoolmen) of medieval universities in Europe from about 1100–1500, and a program of employing that method in articulating and defending orthodoxy in an increasingly pluralistic context. It originated as an outgrowth of, and a departure from, Christian monastic schools.

Not so much a philosophy or a theology as a method of learning, scholasticism places a strong emphasis on dialectical reasoning to extend knowledge by inference, and to resolve contradictions. Scholastic thought is also known for rigorous conceptual analysis and the careful drawing of distinctions. In the classroom and in writing, it often takes the form of explicit disputation: a topic drawn from the tradition is broached in the form of a question, opponents' responses are given, a counterproposal is argued and opponent's arguments rebutted. Because of its emphasis on rigorous dialectical method, scholasticism was eventually applied to many other fields of study.

As a program, scholasticism began as an attempt at harmonization on the part of medieval Christian thinkers: to harmonize the various authorities of their own tradition, and to reconcile Christian theology with classical and late antiquity philosophy, especially that of Aristotle but also of Neoplatonism. (See also Christian apologetics.)

The main figures of scholasticism historically are Anselm of Canterbury, Peter Abelard, Alexander of Hales, Albertus Magnus, Duns Scotus, William of Ockham, Bonaventure and Thomas Aquinas. Thomas Aquinas's masterwork, the Summa Theologica, is often seen as the highest fruit of Scholasticism. Important work in the scholastic tradition has been carried on, however, well past Aquinas' time, for instance by Francisco Suárez and Molina, and also among Lutheran and Reformed thinkers.

-- Scholasticism, by Wikipedia

The Eclectic Jews, and their followers, the Ammonian and Christian Platonics, who endeavoured to make their own philosophy and religion conform to the ancient theology, held infinity of space to be only the immensity of the divine presence. Ὁ Θεος ἑαντσ τοπος εστι [22] was their dogma, which is now inserted into the Confessional of the Greek Church. [23] This infinity was distinguished by them from common space, as time was from eternity. Whatever is eternal or infinite, said they, must be absolutely indivisible; because division is in itself inconsistent with infinite continuity and duration: therefore space and time are distinct from infinity and eternity, which are void of all parts and gradations whatever. Time is measured by years, days, hours, &c., and distinguished by past, present, and future; but these, being divisions, are excluded from eternity, as locality is from infinity, and as both are from the Being who fills both; who can therefore feel no succession of events, nor know any gradation of distance; but must comprehend infinite duration as if it were one moment, and infinite extent as if it were but a single point. [24] Hence the Ammonian Platonics speak of him as concentered in his own unity, and extended through all things, but participated of by none. Being of a nature more refined and elevated than intelligence itself, he could not be known by sense, perception, or reason; and being the cause of all, he must be anterior to all, even to eternity itself, if considered as eternity of time, and not as the intellectual unity, which is the Deity himself, by whose emanations all things exist, and to whose proximity or distances they owe their degrees of excellence or baseness. Being itself, in its most abstract sense, is derived from him; for that which is the cause and beginning of all Being, cannot be a part of that All which sprung from himself: therefore he is not Being, nor is Being his Attribute; for that which has an attribute cannot have the abstract simplicity of pure unity. All Being is in its nature finite; for, if it was otherwise, it must be without bounds every way; and therefore could have no gradation of proximity to the first cause, or consequent pre-eminence of one part over another: for, as all distinctions of time are excluded from infinite duration, and all divisions of locality from infinite extent, so are all degrees of priority from infinite progression. The mind is and acts in itself; but the abstract unity of the first cause is neither in itself, nor in another; -- not in itself, because that would imply modification, from which abstract simplicity is necessarily exempt; nor in another, because then there would be an hypostatical duality, instead of absolute unity. In both cases there would be a locality of hypostasis, inconsistent with intellectual infinity. As all physical attributes were excluded from this metaphysical abstraction, which they called their first cause, he must of course be destitute of all moral ones, which are only generalized modes of action of the former. Even simple abstract truth was denied him; for truth, as Proclus says, is merely the relative to falsehood; and no relative can exist without a positive or correlative. The Deity therefore who has no falsehood, can have no truth, in our sense of the word. [25]

As metaphysical theology is a study very generally, and very deservedly, neglected at present, I thought this little specimen of it might be entertaining, from its novelty, to most readers; especially as it is intimately connected with the ancient system, which I have here undertaken to examine. Those, who wish to know more of it, may consult Proclus on the Theology of Plato, where they will find the most exquisite ingenuity most wantonly wasted. No persons ever showed greater acuteness or strength of reasoning than the Platonics and Scholastics; but having quitted common sense, and attempted to mount into the intellectual world, they expended it all in abortive efforts which may amuse the imagination, but cannot satisfy the understanding.

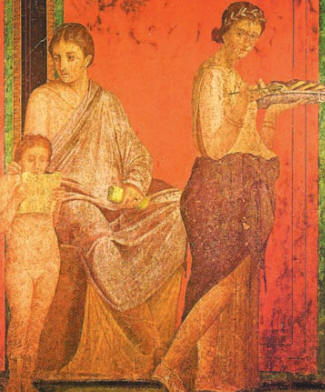

The ancient Theologists showed more discretion; for, finding that they could conceive no idea of infinity, they were content to revere the Infinite Being in the most general and efficient exertion of his power, attraction; whose agency is perceptible through all matter, and to which all motion may, perhaps, be ultimately traced. This power, being personified, became the secondary Deity, to whom all adoration and worship were directed, and who is therefore frequently considered as the sole and supreme cause of all things. His agency being supposed to extend through the whole material world, and to produce all the various revolutions by which its system is sustained, his attributes were of course extremely numerous and varied. These were expressed by various titles and epithets in the mystic hymns and litanies, which the artists endeavoured to represent by various forms and characters of men and animals. The great characteristic attribute was represented by the organ of generation in that state of tension and rigidity which is necessary to the due performance of its functions. Many small images of this kind have been found among the ruins of Herculaneum and Pompeii, attached to the bracelets, which the chaste and pious matrons of antiquity wore round their necks and arms. In these, the organ of generation appears alone, or only accompanied with the wings of incubation, [26] in order to show that the devout wearer devoted herself wholly and solely to procreation, the great end for which she was ordained. So expressive a symbol, being constantly in her view, must keep her attention fixed on its natural object, and continually remind her of the gratitude she owed the Creator, for having taken her into his service, made her a partaker of his most valuable blessings, and employed her as the passive instrument in the exertion of his most beneficial power.

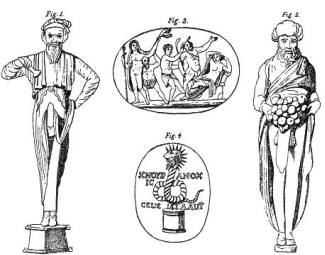

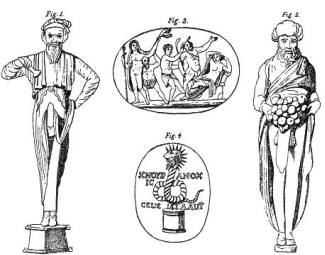

PLATE 5: FIGURES OF PAN AND GEMS

PLATE 5: FIGURES OF PAN AND GEMSThe female organs of generation were revered [27] as symbols of the generative powers of nature or matter, as the male were of the generative powers of God. They are usually represented emblematically, by the Shell, or Concha Veneris, which was therefore worn by devout persons of antiquity, as it still continues to be by pilgrims, and many of the common women of Italy. The union of both was expressed by the hand mentioned in Sir William Hamilton's letter; [28] which being a less explicit symbol, has escaped the attention of the reformers, and is still worn, as well as the shell, by the women of Italy, though without being understood. It represented the act of generation, which was considered as a solemn sacrament, in honour of the Creator, as will be more fully shown hereafter.

The male organs of generation are sometimes found represented by signs of the same sort, which might properly be called the symbols of symbols. One of the most remarkable of these is a cross, in the form of the letter T, [29] which thus served as the emblem of creation and generation, before the church adopted it as the sign of salvation; a lucky coincidence of ideas, which, without doubt, facilitated the reception of it among the faithful. To the representative of the male organs was sometimes added a human head, which gives it the exact appearance of a crucifix; as it has on a medal of Cyzicus, published by M. Pellerin. [30] On an ancient medal, found in Cyprus, which, from the style of workmanship, is certainly anterior to the Macedonian conquest, it appears with the chaplet or rosary, such as is now used in the Romish churches; [31] the beads of which were used, anciently, to reckon time. [32] Their being placed in a circle, marked its progressive continuity; while their separation from each other marked the divisions, by which it is made to return on itself, and thus produce years, months, and days. The symbol of the creative power is placed upon them, because these divisions were particularly under his influence and protection; the sun being his visible image, and the centre of his power, from which his emanations extended through the universe. Hence the Egyptians, in their sacred hymns, called upon Osiris, as the being who dwelt concealed in the embraces of the sun; [33] and hence the great luminary itself is called Κοσμοκρατωζ (Ruler of the World) in the Orphic Hymns. [34]

This general emanation of the pervading Spirit of God, by which all things are generated and maintained, is beautifully described by Virgil, in the following lines:

Deum namque ire per omnes

Terrasque, tractusque maris, coelumque profundum.

Hinc pecudes, armenta, viros, genus omne ferarum,

Quemque sibi tenues nascentum arcessere vitas.

Scilicet huc reddi deinde, ac resoluta referri

Omnia: nec morti esse locum, sed viva volare

Sideris in numerum, atque alto succedere coelo. [35]

[Google translate: For God permeates all

And lands, and the expanse of the sea, the depths of heaven.

From whom flocks, herds, men, beasts of every kind,

Draw each at birth the fine essential flame.

Of course, then return here, and the resolution referred

All: nor can death Find place, but a living to fly

In the number of star, and take its place on high heaven.]

The Ethereal Spirit is here described as expanding itself through the universe, and giving life and motion to the inhabitants of earth, water, and air, by a participation of its own essence, each particle of which returned to its native source, at the dissolution of the body which it animated. Hence, not only men, but all animals, and even vegetables, were supposed to be impregnated with some particles of the Divine Nature infused into them, from which their various qualities and dispositions, as well as their powers of propagation, were supposed to be derived. These appeared to be so many emanations of the Divine attributes, operating in different modes and degrees, according to the nature of the beings to which they belonged. Hence the characteristic properties of animals and plants were not only regarded as representations, but as actual emanations of the Divine Power, consubstantial [of the same substance] with his own essence. [36] For this reason, the symbols were treated with greater respect and veneration than if they had been merely signs and characters of convention. Plutarch says, that most of the Egyptian priests held the bull Apis, who was worshipped with so much ceremony, to be only an image of the Spirit of Osiris. [37] This I take to have been the real meaning of all the animal worship of the Egyptians, about which so much has been written, and so little discovered. Those animals or plants, in which any particular attribute of the Deity seemed to predominate, became the symbols of that attribute, and were accordingly worshipped as the images of Divine Providence, acting in that particular direction. Like many other customs, both of ancient and modern worship, the practice, probably, continued long after the reasons upon which it was founded were either wholly lost, or only partially preserved, in vague traditions. This was the case in Egypt; for, though many of the priests knew or conjectured the origin of the worship of the bull, they could give no rational account why the crocodile, the ichneumon, and the ibis, received similar honours. The symbolical characters, called hieroglyphics, continued to be esteemed by them as more holy and venerable than the conventional representations of sounds, notwithstanding their manifest inferiority; yet it does not appear, from any accounts extant, that they were able to assign any reason for this preference. On the contrary, Strabo tells us that the Egyptians of his time were wholly ignorant of their ancient learning and religion, [38] though impostors continually pretended to explain it. Their ignorance in these points is not to be wondered at, considering that the most ancient Egyptians, of whom we have any authentic accounts, lived after the subversion of their monarchy and destruction of their temples by the Persians, who used every endeavour to annihilate their religion; first, by command of Cambyses, [39] and then of Ochus. [40] What they were before this calamity, we have no direct information; for Herodotus is the earliest traveller, and he visited this country when in ruins.

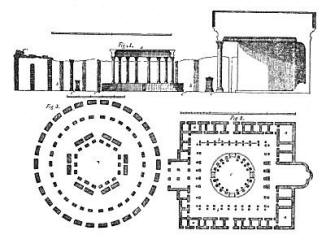

PLATE 6: THE TAURIC DIANA

PLATE 6: THE TAURIC DIANA_______________

Notes:1. Plut. de Is. et Os.

2. Plut. de Is. et Os.

3. Ibid.

4. Orph. Argon. 422.

5. Orph. Argon., ver. 12. This poem of the Argonautic Expedition is not of the ancient Orpheus, but written in his name by some poet posterior to Homer; as appears by the allusion to Orpheus's descent into hell; a fable invented after the Homeric times. It is, however, of very great antiquity, as both the style and manner sufficiently prove; and, I think, cannot be later than the age of Pisistratus, to which it has been generally attributed. The passage here referred to is cited from another poem, which, at the time this was written, passed for a genuine work of the Thracian bard: whether justly or not, matters little; for its being thought so at that time proves it to be of the remotest antiquity. The other Orphic poems cited in this discourse are the Hymns, or Litanies, which are attributed by the early Christian and later Platonic writers to Onomacritus, a poet of the age of Pisistratus; but which are probably of various authors (See Brucker. Hist. Crit. Philos., vol. I., part 2, lib., c. i.) They contain, however, nothing which proves them to he later than the Trojan times; and if Onomacritus, or any later author, had anything to do with them, it seems to have been only in new-versifying them, and changing the dialect (See Gesner. Proleg. Orphica, p. 26). Had he forged them, and attempted to impose them upon the world, as the genuine compositions of an ancient bard, there can be no doubt but that he would have stuffed them with antiquated words and obsolete phrases; which is by no means the case, the language being pure and worthy the age of Pisistratus. These Poems are not properly hymns, for the hymns of the Greeks contained the nativities and actions of the gods, like those of Homer and Callimachus; but these are compositions of a different kind, and are properly invocations or prayers used in the Orphic mysteries, and seem nearly of the same class as the Psalms of the Hebrews. The reason why they are so seldom mentioned by any of the early writers, and so perpetually referred to by the later, is that they belonged to the mystic worship, where everything was kept concealed under the strictest oaths of secrecy. But after the rise of Christianity, this sacred silence was broken by the Greek converts who revealed everything which they thought would depreciate the old religion or recommend the now; whilst the heathen priests revealed whatever they thought would have contrary tendency; and endeavoured to show, by publishing the real mystic creed of their religion, that the principles of it were not so absurd as its outward structure seemed to infer; but that, when stripped of poetical allegory and vulgar fable, their theology was pure, reasonable, and sublime (Gesner. Proleg. Orphica). The collection of these poems now extant, being probably compiled and versified by several hands, with some forged, and other interpolated and altered, must be read with great caution; more especially the Fragments preserved by the Fathers of the Church and Ammonian Platonics; for these writers made no scruple of forging any monuments of antiquity which suited their purposes; particularly the former, who, in addition to their natural zeal, having the interests of a confederate body to support, thought every means by which they could benefit that body, by extending the lights of revelation, and gaining proselytes to the true faith, not only allowable, but meritorious (See Clementina, Hom. vii., see. 10. Recogn. lib. i., sec. 65. Origen, apud Hieronom. Apolog. i., contra Ruf. et Chrysostom. de Sacerdot., lib. i. Chrysostom, in particular, not only Justifies, but warmly commends, any frauds that can be practiced for the advantage of the Church of Christ). Pausanias says (lib. ix.), that the Hymns of Orpheus were few and short; but next in poetical merit to those of Homer, and superior to them in sanctity (θεολογικωτεροι). These are probably the same as the genuine part of the collection now extant; but they are so intermixed, that it is difficult to say which are genuine and which are not. Perhaps there is no surer rule for judging than to compare the epithets and allegories with the symbols and monograms on the Greek medals, and to make their agreement the test of authenticity. The medals were the public acts and records of the State, made under the direction of the magistrates, who were generally initiated into the mysteries. We may therefore be assured, that whatever theological and mythological allusions are found upon them were part of the ancient religion of Greece. It is from these that many of the Orphic Hymns and Fragments are proved to contain the pure theology or mystic faith of the ancients, which is called Orphic by Pausanias (lib. i., c. 39), and which is so unlike the vulgar religion, or poetical mythology, that one can scarcely imagine at first sight that it belonged to the same people; but which will nevertheless appear, upon accurate investigation, to be the source from whence it flowed, and the cause of all its extravagance.

The history of Orpheus himself is so confused and obscured by fable, that it is impossible to obtain any certain information concerning him. According to general tradition, he was a Thracian, and introduced the mysteries, in which a more pure system of religion was taught, into Greece (Brucker, vol. i., part 2, lib. i., c. i.) He is also said to have travelled into Egypt (Diodor. Sic. lib. i., p. 80); but as the Egyptians pretended that all foreigners received their sciences from them, at a time when all foreigners who entered the country were put to death or enslaved (Diodor. Sic. lib. i., pp. 78 et 107), this account may be rejected, with many others of the same kind. The Egyptians certainly could not have taught Orpheus the plurality of worlds, and true solar system, which appear to have been the fundamental principles of his philosophy and religion (Plutarch. de Placit. Philos., lib. ii., c. 13. Brucker in loc. citat.) Nor could he have gained this knowledge from any people which history has preserved any memorials; for we know of none among whom science had made such a progress, that a truth so remote from common observation, and so contradictory to the evidence of unimproved sense, would not have been rejected, as it was by all the sects of Greek philosophy except the Pythagoreans, who rather revered it as an article of faith, than understood it as a discovery of science. Thrace was certainly inhabited by a civilized nation at some remote period; for, when Philip of Macedon opened the gold mines in that country, he found that they had been worked before with great expense and ingenuity, by a people well versed in mechanics, of whom no memorials whatever were then extant. Of these, probably, was Orpheus, as well as Thamyris, both of whose poems, Plato says, could be read with pleasure in his time.

6. See Sophocl. (Edip. Tyr., ver. 1436.

7. Orph. Hym. 5.

8. Symph. l. 2.

9. See Plate 21. Fig. 1.

10. Macrob. Sat. i. c. 20.

11. See Goltz, Tab. II. Figs. 7 and 8.

12. See Plate 4. Fig. 1, and Recherches sur les Arts, vol. i. Pl. VIII. The Hebrew word Chroub, or Cherub, signified originally strong or robust; but is usually employed metaphorically, signifying a Bull. See Cleric. In Exod. c. XXV.

13. Recherches sur les Arts, lib. 1.

14. Lib. i. c. 12.

15. Exod. c. XXXIV. v. 35, ed. Vulgat. Other translators understand the expression metaphorically, and suppose it to mean radiated, or luminous.

16. See Plate 3.

17. Τον δε τραγον αωεθεωσαν (οι Αιγνωτιοι) χαθαωερ και ωαρα τοις Ελλησι τετιησθαι λεγξι τον Πριαωον, δια το γεννητικον μοριον. DIODOR. lib. i. p. 78.

18. Plate 10. Fig. 3.

19. Orph. Hymn. v. et xxix.

20. Numm. Vet. Pop. et Urb. Tab. xxxix. Figs 19 et 20. They are on most of the medals of Marseilles, Naples, Thurium and many other cities.

21. In Tim. III., et Frag. Orphic., ed. Gesner.

22. Philo. de Leg. Alleg. lib. 1. Jo Damasc de Orth Fid.

23. Mosheim. Nota in Sec. xxiv. Cudw. Syst. Intellect.

24. See Boeth. de Consol. Philos. lib. iv. prof. 6.

25. Proclus in Theolog. Platon. lib. i. et ii.

26. Plate 2. Fig. 2, engraved from one in the British Museum.

27. August. de Civ. Dei, Lib. VI. c. 9.

28. See Plate 2, Fig. 1. from one in the British Museum, in which both symbols are united.

29. Recherches our les Arts, lib. i. c. 3.

30. See Plate 9. Fig. 1.

31. Plate 9. Fig. 2, from Pellerin. Similar medals are in the Hunter Collection, and are evidently of Phoenician work.

32. Recherches our les Arts, lib. i. c. 3.

33. Plutarch. de Is. et Osir.

34. See Hymn VII.

35. Georgic. lib. iv. ver. 221.

36. Proclus in Theol. Plat. lib. i. pp. 56, 57.

37. De Is. et Os.

38. Lib. xvii.

39. Herodot. lib. iii. Strabo, lib. xvii.

40. Plutarch. de Is. et Os.