The appearance of the hero Chiwantopel on horseback -- Hero and horse equivalent of humanity and its repressed libido -- Horse a libido symbol, partly phallic, partly maternal, like the tree -- It represents the libido repressed through the incest prohibition -- The scene of Chiwantopel and the Indian -- Recalling Cassius and Brutus: also delirium of Cyrano -- Identification of Cassius with his mother -- His infantile disposition -- Miss Miller's hero also infantile -- Her visions arise from an infantile mother transference -- Her hero to die from an arrow wound -- The symbolism of the arrow -- The onslaught of unconscious desires -- The deadly arrows strike the hero from within -- It means the state of introversion -- A sinking back into the world of the child -- The danger of this regression -- It may mean annihilation or new life -- Examples of introversion -- The clash between the retrogressive tendency in the individual unconscious and the conscious forward striving -- Willed introversion -- The unfulfilled sacrifice in the Miller phantasy means an attempt to renounce the mother: the conquest of a new life through the death of the old -- The hero Miss Miller herself.

THERE now comes a pause in the production of visions by Miss Miller; then the activity of the unconscious is resumed very energetically.

A forest with trees and bushes appears.

After the discussions in the preceding chapter, there is need only of a hint that the symbol of the forest coincides essentially with the meaning of the holy tree. The holy tree is found generally in a sacred forest inclosure or in the garden of Paradise. The sacred grove often takes the place of the taboo tree and assumes all the attributes of the latter. The erotic symbolism of the garden is generally known. The forest, like the tree, has mythologically a maternal significance. In the vision which now follows, the forest furnishes the stage upon which the dramatic representation of the end of Chiwantopel is played. This act, therefore, takes place in or near the mother.

First, I will give the beginning of the drama as it is in the original text, up to the first attempt at sacrifice. At the beginning of the next chapter the reader will find the continuation, the monologue and the sacrificial scene. The drama begins as follows:

"The personage Chiwantopel, came from the south, on horse back; around him a cloak of vivid colors, red, blue and white. An Indian in a costume of doe skin, covered with beads and ornamented with feathers advances, squats down and prepares to let fly an arrow at Chiwantopel. The latter presents his breast in an attitude of defiance, and the Indian, fascinated by that sight, slinks away and disappears within the forest."

The hero, Chiwantopel, appears on horseback. This fact seems of importance, because as the further course of the drama shows (see Chapter VIII) the horse plays no indifferent role, but suffers the same death as the hero, and is even called "faithful brother" by the latter. These allusions point to a remarkable similarity between horse and rider. There seems to exist an intimate connection between the two, which guides them to the same destiny. We already have seen that the symbolization of "the libido in resistance" through the "terrible mother" in some places runs parallel with the horse. [1] Strictly speaking, it would be incorrect to say that the horse is, or means, the mother. The mother idea is a libido symbol, and the horse is also a libido symbol, and at some points the two symbols intersect in their significances. The common feature of the two ideas lies in the libido, especially in the libido repressed from incest. The hero and the horse appear to us in this setting like an artistic formation of the idea of humanity with its repressed libido, whereby the horse acquires the significance of the animal unconscious, which appears domesticated and subjected to the will of man. Agni upon the ram, Wotan upon Sleipneir, Ahuramazda upon Angromainyu, [2] Jahwe upon the monstrous seraph, Christ upon the ass, [3] Dionysus upon the ass, Mithra upon the horse, Men upon the human-footed horse, Freir upon the golden-bristled boar, etc., are parallel representations. The chargers of mythology are always invested with great significance; they very often appear anthropomorphized. Thus, Men's horse has human forelegs; Balaam's ass, human speech; the retreating bull, upon whose back Mithra springs in order to strike him down, is, according to a Persian legend, actually the God himself. The mock crucifix of the Palatine represents the crucified with an ass's head, perhaps in reference to the ancient legend that in the temple of Jerusalem the image of an ass was worshipped. As Drosselbart (horse's mane) Wotan is half-human, half-horse. [4] An old German riddle very prettily shows this unity between horse and horseman. [5] "Who are the two, who travel to Thing? Together they have three eyes, ten feet [6] and one tail; and thus they travel over the land." Legends ascribe properties to the horse, which psychologically belong to the unconscious of man; horses are clairvoyant and clairaudient; they show the way when the lost wanderer is helpless; they have mantic powers. In the Iliad the horse prophesies evil. They hear the words which the corpse speaks when it is taken to the grave words which men cannot hear. Caesar learned from his human-footed horse (probably taken from the identification of Caesar with the Phrygian Men) that he was to conquer the world. An ass prophesied to Augustus the victory of Actium. The horse also sees phantoms. All these things correspond to typical manifestations of the unconscious. Therefore, it is perfectly intelligible that the horse, as the image of the wicked animal component of man, has manifold connections with the devil. The devil has a horse's foot; in certain circumstances a horse's form. At crucial moments he suddenly shows a cloven foot (proverbial) in the same way as in the abduction of Hadding, Sleipneir suddenly looked out from behind Wotan's mantle. [7] Just as the nightmare rides on the sleeper, so does the devil, and, therefore, it is said that those who have nightmares are ridden by the devil. In Persian lore the devil is the steed of God. The devil, like all evil things, represents sexuality. Witches have intercourse with him, in which case he appears in the form of a goat or horse. The unmistakably phallic nature of the devil is communicated to the horse as well; hence this symbol occurs in connections where this is the only meaning which would furnish an explanation. It is to be mentioned that Loki generates in the form of a horse, just as does the devil when in horse's form, as an old fire god. Thus the lightning was represented theriomorphically as a horse. [8] An uneducated hysteric told me that as a child she had suffered from extreme fear of thunder, because every time the lightning flashed she saw immediately afterwards a huge black horse reaching upwards as far as the sky. [9] It is said in a legend that the devil, as the divinity of lightning, casts a horse's foot (lightning) upon the roofs. In accordance with the primitive meaning of thunder as fertilizer of the earth, the phallic meaning is given both to lightning and the horse's foot. In mythology the horse's foot really has the phallic function as in this dream. An uneducated patient who originally had been violently forced to coitus by her husband very often dreams (after separation) that a wild horse springs upon her and kicks her in the abdomen with his hind foot Plutarch has given us the following words of a prayer from the Dionysus orgies:

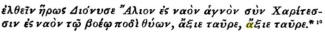

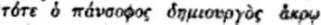

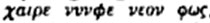

[i] [10]

[i] [10]Pegasus with his foot strikes out of the earth the spring Hippocrene. Upon a Corinthian statue of Bellerophon, which was also a fountain, the water flowed out from the horse's hoof. Balder's horse gave rise to a spring through his kick. Thus the horse's foot is the dispenser of fruitful moisture. [11] A legend of lower Austria, told by Jaehns, informs us that a gigantic man on a white horse is sometimes seen riding over the mountains. This means a speedy rain. In the German legend the goddess of birth, Frau Holle, appears on horseback. Pregnant women near confinement are prone to give oats to a white horse from their aprons and to pray him to give them a speedy delivery. It was originally the custom for the horse to rub against the woman's genitals. The horse (like the ass) had in general the significance of a priapic animal. [12] Horse's tracks are idols dispensing blessing and fertility. Horse's tracks established a claim, and were of significance in determining boundaries, like the priaps of Latin antiquity. Like the phallic Dactyli, a horse opened the mineral riches of the Harz Mountains with his hoof. The horseshoe, an equivalent for horse's foot, [13] brings luck and has apotropaic meaning. In the Netherlands an entire horse's foot is hung up in the stable to ward against sorcery. The analogous effect of the phallus is well known; hence the phalli at the gates. In particular the horse's leg turned lightning aside, according to the principle "similia similibus."

Horses also symbolize the wind, that is to say, the tertium comparationis is again the libido symbol. The German legend recognizes the wind as the wild huntsman in pursuit of the maiden. Stormy regions frequently derive their names from horses, as the White Horse Mountain of the Luneburger heath. The centaurs are typical wind gods, and have been represented as such by Bocklin's artistic intuition. [14]

Horses also signify fire and light. The fiery horses of Helios are an example. The horses of Hector are called Xanthos (yellow, bright), Podargos (swift-footed), Lampos (shining) and Aithon (burning). A very pronounced fire symbolism was represented by the mystic Quadriga, mentioned by Dio Chrysostomus. The supreme God always drives his chariot in a circle. Four horses are harnessed to the chariot. The horse driven on the periphery moves very quickly. He has a shining coat, and bears upon it the signs of the planets and the Zodiac. [15] This is a representation of the rotary fire of heaven. The second horse moves more slowly, and is illuminated only on one side. The third moves still more slowly, and the fourth rotates around himself. But once the outer horse set the second horse on fire with his fiery breath, and the third flooded the fourth with his streaming sweat. Then the horses dissolve and pass over into the substance of the strongest and most fiery, which now becomes the charioteer. The horses also represent the four elements. The catastrophe signifies the conflagration of the world and the deluge, whereupon the division of the God into many parts ceases, and the divine unity is restored. [16] Doubtless the Quadriga may be understood astronomically as a symbol of time. We already saw in the first part that the stoic representation of Fate is a fire symbol. It is, therefore, a logical continuation of the thought, when time, closely related to the conception of destiny, exhibits this same libido symbolism. Brihadaranyaka-Upanishad, i: i, says:

"The morning glow verily is the head of the sacrificial horse, the sun his eye, the wind his breath, the all-spreading fire his mouth, the year is the belly of the sacrificial horse. The sky is his back, the atmosphere the cavern of his body, the earth the vault of his belly. The poles are his sides, in between the poles his ribs, the seasons his limbs, the months and fortnights his joints. Days and nights are his feet, stars his bones, clouds his flesh. The food he digests is the deserts, the rivers are his veins, the mountains his liver and lungs, the herbs and trees his hair; the rising sun is his fore part, the setting sun his after part. The ocean is his kinsman, the sea his cradle."

The horse undoubtedly here stands for a time symbol, and also for the entire world. We come across in the Mithraic religion, a strange God of Time, Aion, called Kronos or Deus Leontocephalus, because his stereotyped representation is a lion-headed man, who, standing in a rigid attitude, is encoiled by a snake, whose head projects forward from behind over the lion's head. The figure holds in each hand a key, on the chest rests a thunderbolt, upon his back are the four wings of the wind; in addition to that, the figure sometimes bears the Zodiac on his body. Additional attributes are a cock and implements. In the Carolingian psalter of Utrecht, which is based upon ancient models, the Saeculum-Aion is represented as a naked man with a snake in his hand. As is suggested by the name of the divinity, he is a symbol of time, most interestingly composed from libido symbols. The lion, the zodiac sign of the greatest summer heat, [17] is the symbol of the most mighty desire. ("My soul roars with the voice of a hungry lion," says Mechthild of Magdeburg.) In the Mithra mystery the serpent is often antagonistic to the lion, corresponding to that very universal myth of the battle of the sun with the dragon.

In the Egyptian Book of the Dead, Tum is even designated as a he-cat, because as such he fought the snake, Apophis. The encoiling also means the engulfing, the entering into the mother's womb. Thus time is defined by the rising and setting of the sun, that is to say, through the death and renewal of the libido. The addition of the cock again suggests time, and the addition of implements suggests the creation through time. ("Duree creatrice," Bergson. ) Oromazdes and Ahriman were produced through Zrwanakarana, the "infinitely long duration." Time, this empty and purely formal concept, is expressed in the mysteries by transformations of the creative power, the libido. Macrobius says:

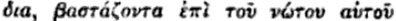

"Leonis capite monstratur praesens tempus quia conditio ejus valida fervensque est." [ii]

Philo of Alexandria has a better understanding:

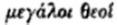

"Tempus ab hominibus pessimis putatur deus volentibus Ens es sentiale abscondere -- pravis hominibus tempus putatur causa rerum mundi, sapientibus vero et optimis non tempus sed Deus." [iii] [18]

In Firdusi [19] time is often the symbol of fate, the libido nature of which we have already learned to recognize. The Hindoo text mentioned above includes still more -- its symbol of the horse contains the whole world; his kinsman and his cradle is the sea, the mother, similar to the world soul, the materna.1 significance of which we have seen above. Just as Aion represents the libido in an embrace, that is to say, in the state of death and of rebirth, so here the cradle of the horse is the sea, i. e. the libido is in the mother, dying and rising again, like the symbol of the dying and resurrected Christ, who hangs like ripe fruit upon the tree of life.

We have already seen that the horse is connected through Ygdrasil with the symbolism of the tree. The horse is also a "tree of death"; thus in the Middle Ages the funeral pyre was called St. Michael's horse, and the neb-Persian word for coffin means u wooden horse." [20] The horse has also the role of psycho-pompos; he is the steed to conduct the souls to the other world -- horse-women fetch the souls (Valkyries). Neo-Greek songs represent Charon on a horse. These definitions obviously lead to the mother symbolism. The Trojan horse was the only means by which the city could be conquered; because only he who has entered the mother and been reborn is an invincible hero. The Trojan horse is a magic charm, like the "Nodfyr," which also serves to overcome necessity. The formula evidently reads, In order to overcome the difficulty, thou must commit incest, and once more be born from thy mother." It appears that striking a nail into the sacred tree signifies something very similar. The "Stock im Eisen" in Vienna seems to have been such a palladium.

Still another symbolic form is to be considered. Occasionally the devil rides upon a three-legged horse. The Goddess of Death, Hel, in time of pestilence, also rides upon a three-legged horse. [21] The gigantic ass, which is three-legged, stands in the heavenly rain lake Vourukasha; his urine purifies the water of the lake, and from his roar all useful animals become pregnant and all harmful animals miscarry. The Triad further points to the phallic significance. The contrasting symbolism of Hel is blended into one conception in the ass of Vourukasha. The libido is fructifying as well as destroying.

These definitions, as a whole, plainly reveal the fundamental features. The horse is a libido symbol, partly of phallic, partly of maternal significance, like the tree. It represents the libido in this application, that is, the libido repressed through the incest prohibition.

In the Miller drama an Indian approaches the hero, ready to shoot an arrow at him. Chiwantopel, however, with a proud gesture, exposes his breast to the enemy. This idea reminds the author of the scene between Cassius and Brutus in Shakespeare's "Julius Caesar." A misunderstanding has arisen between the two friends, when Brutus reproaches Cassius for withholding from him the money for the legions. Cassius, irritable and angry, breaks out into the complaint:

"Come, Antony, and young Octavius, come,

Revenge yourselves alone on Cassius,

For Cassius is a-weary of the world :

Hated by one he loves: braved by his brother:

Check'd like a bondman; all his faults observed:

Set in a note-book, learn'd and conn'd by rote,

To cast into my teeth. O I could weep

My spirit from mine eyes! -- There is my dagger,

And here my naked breast; within, a heart

Dearer than Plutus' mine, richer than gold :

If that thou beest a Roman, take it forth:

I, that denied thee gold, will give my heart.

Strike, as thou didst at Caesar; for I know

When thou didst hate him worst, thou lov'dst him better

Than ever thou lov'dst Cassius."

The material here would be incomplete without mentioning the fact that this speech of Cassius shows many analogies to the agonized delirium of Cyrano (compare Part I), only Cassius is far more theatrical and overdrawn. Something childish and hysterical is in his manner. Brutus does not think of killing him, but administers a very chilling rebuke in the following dialogue:

BRUTUS: Sheathe your dagger:

Be angry when you will, it shall have scope:

Do what you will, dishonor shall be humor.

O Cassius, you are yoked with a lamb

That carries anger as the flint bears fire:

Who, much enforced, shows a hasty spark,

And straight is cold again.

CASSIUS: Hath Cassius liv'd

To be but mirth and laughter to his Brutus

When grief and blood ill-tempered vexeth him?

BRUTUS: When I spoke that, I was ill-tempered too.

CASSIUS: Do you confess so much? Give me your hand.

BRUTUS: And my heart too.

CASSIUS: O Brutus!

BRUTUS: What's the matter?

CASSIUS: Have not you love enough to bear with me

When that rash humor which my mother gave me

Makes me forgetful?

BRUTUS: Yes, Cassius, and from henceforth

When you are over earnest with your Brutus,

He'll think your mother chides and leave you so.

The analytic interpretation of Cassius's irritability plainly reveals that at these moments he identifies himself with the mother, and his conduct, therefore, is truly feminine, as his speech demonstrates most excellently. For his womanish love-seeking and desperate subjection under the proud masculine will of Brutus calls forth the friendly remark of the latter, that Cassius is yoked with a lamb, that is to say, has something very weak in his character, which is derived from the mother. One recognizes in this without any difficulty the analytic hall-marks of an infantile disposition, which, as always, is characterized by a prevalence of the parent-imago, here the mother-imago. An infantile individual is infantile because he has freed himself insufficiently, or not at all, from the childish environment, that is, from his adaptation to his parents. Therefore, on one side, he reacts falsely towards the world, as a child towards his parents, always demanding love and immediate reward for his feelings; on the other side, on account of the close connection to the parents, he identifies himself with them. The infantile individual behaves like the father and mother. He is not in a condition to live for himself and to find the place to which he belongs. Therefore, Brutus very justly takes it for granted that the "mother chides" in Cassius, not he himself. The psychologically valuable fact which we gather here is the information that Cassius is infantile and identified with the mother. The hysterical behavior is due to the circumstance that Cassius is still, in part, a lamb, and an innocent and entirely harmless child. He remains, as far as his emotional life is concerned, still far behind himself. This we often see among people who, as masters, apparently govern life and fellow-creatures; they have remained children in regard to the demands of their love nature.

The figures of the Miller dramas, being children of the creator's phantasy, depict, as is natural, those traits of character which belong to the author. The hero, the wish figure, is represented as most distinguished, because the hero always combines in himself all wished-for ideals. Cyrano's attitude is certainly beautiful and impressive; Cassius's behavior has a theatrical effect. Both heroes prepare to die effectively, in which attempt Cyrano succeeds. This attitude betrays a wish for death in the unconscious of our author, the meaning of which we have already discussed at length as the motive for her poem of the moth. The wish of young girls to die is only an indirect expression, which remains a pose, even in case of real death, for death itself can be a pose. Such an outcome merely adds beauty and value to the pose under certain conditions. That the highest summit of life is expressed through the symbolism of death is a well-known fact; for creation beyond one's self means personal death. The coming generation is the end of the preceding one. This symbolism is frequent in erotic speech. The lascivious speech between Lucius and the wanton servant-maid in Apuleius ("Metamorphoses," lib. ii: 32) is one of the clearest examples:

"Proeliare, inquit, et fortiter proeliare : nee enim tibi cedam, nee terga vortam. Cominus in aspectum, si vir es, dirige; et grassare naviter, et occide moriturus. Hodierna pugna non habet missionem. -- Simul ambo corruimus inter mutuos amplexus animas anhelantes." [iv]

This symbolism is extremely significant, because it shows how easily a contrasting expression originates and how equally intelligible and characteristic such an expression is. The proud gesture with which the hero offers himself to death may very easily be an indirect expression which challenges the pity or sympathy of the other, and thus is doomed to the calm analytic reduction to which Brutus proceeds. The behavior of Chiwantopel is also suspicious, because the Cassius scene which serves as its model betrays indiscreetly that the whole affair is merely infantile and one which owes its origin to an overactive mother imago. When we compare this piece with the series of mother symbols brought to light in the previous chapter, we must say that the Cassius scene merely confirms once more what we 'have long supposed, that is to say, that the motor power of these symbolic visions arises from an infantile mother transference, that is to say, from an undetached bond to the mother.

In the drama the libido, in contradistinction to the inactive nature of the previous symbols, assumes a threatening activity, a conflict becoming evident, in which the one part threatens the other with murder. The hero, as the ideal image of the dreamer, is inclined to die; he does not fear death. In accordance with the infantile character of this hero, it would most surely be time for him to take his departure from the stage, or, in childish language, to die. Death is to come to him in the form of an arrow-wound. Considering the fact that heroes themselves are very often great archers or succumb to an arrow-wound (St. Sebastian, as an example), it may not be superfluous to inquire into the meaning of death through an arrow.

We read in the biography of the stigmatized nun Katherine Emmerich [22] the following description of the evidently neurotic sickness of her heart:

"When only in her novitiate, she received as a Christmas present from the holy Christ a very tormenting heart trouble for the whole period of her nun's life. God showed her inwardly the purpose; it was on account of the decline of the spirit of the order, especially for the sins of her fellow-sisters. But what rendered this trouble most painful was the gift which she had possessed from youth, namely, to see before her eyes the inner nature of man as he really was. She felt the heart trouble physically as if her heart was continually pierced by arrows. [23] These arrows -- and this represented the still worse mental suf fering -- she recognized as the thoughts, plots, secret speeches, misunderstandings, scandal and uncharitableness, in which her fellow-sisters, wholly without reason and unscrupulously, were engaged against her and her god-fearing way of life."

It is difficult to be a saint, because even a patient and long-suffering nature will not readily bear such a violation, and defends itself in its own way. The companion of sanctity is temptation, without which no true saint can live. We know from analytic experience that these temptations can pass unconsciously, so that only their equivalents would be produced in consciousness in the form of symptoms. We know that it is proverbial that heart and smart (Herz and Schmerz) rhyme. It is a well-known fact that hysterics put a physical pain in place of a mental pain. The biographer of Emmerich has comprehended that very correctly. Only her interpretation of the pain is, as usual, projected. It is always the others who secretly assert all sorts of evil things about her, and this she pretended gave her the pains. [24] The case, however, bears a somewhat different aspect. The very difficult renunciation of all life's joys, this death before the bloom, is generally painful, and especially painful are the unfulfilled wishes and the attempts of the animal nature to break through the power of repression. The gossip and jokes of the sisters very naturally centre around these most painful things, so that it must appear to the saint as if her symptoms were caused by this. Naturally, again, she could not know that gossip tends to assume the role of the unconscious, which, like a clever adversary, always aims at the actual gaps in our armor.

A passage from Gautama Buddha embodies this idea: [25]

"A wish earnestly desired

Produced by will, and nourished

When gradually it must be thwarted,

Burrows like an arrow in the flesh."

The wounding and painful arrows do not come from without through gossip, which only attacks externally, but they come from ambush, from our own unconscious. This, rather than anything external, creates the defenseless suffering. It is our own repressed and unrecognized desires which fester like arrows in our flesh. [26] In another connection this was clear to the nun, and that most literally. It is a well-known fact, and one which needs no further proof to those who understand, that these mystic scenes of union with the Saviour generally are intermingled with an enormous amount of sexual libido. [27] Therefore, it is not astonishing that the scene of the stigmata is nothing but an incubation through the Saviour, only slightly changed metaphorically, as compared with the ancient conception of "unio mystica," as cohabitation with the god. Emmerich relates the following of her stigmatization:

"I had a contemplation of the sufferings of Christ, and implored him to let me feel with him his sorrows, and prayed five paternosters to the honor of the five sacred wounds. Lying on my bed with outstretched arms, I entered into a great sweetness and into an endless thirst for the torments of Jesus. Then I saw a light descending upon me: it came obliquely from above. It was a crucified body, living and transparent, with arms extended, but without a cross. The wounds shone brighter than the body; they were five circles of glory, coming forth from the whole glory. I was enraptured and my heart was moved with great pain and yet with sweetness from longing to share in the torments of my Saviour. And my longings for the sorrows of the Redeemer increased more and more on gazing on his wounds, and passed from my breast, through my hands, sides and feet to his holy wounds: then from the hands, then from the sides, then from the feet of the figure threefold shining red beams ending below in an arrow, shot forth to my hands, sides and feet."

The beams, in accordance with the phallic fundamental thought, are threefold, terminating below in an arrow-point. [28] Like Cupid, the sun, too, has its quiver, full of destroying or fertilizing arrows, sun rays, [29] which possess phallic meaning. On this significance evidently rests the Oriental custom of designating brave sons as arrows and javelins of the parents. "To make sharp arrows" is an Arabian expression for "to generate brave sons." The Psalms declare (cxxvii:4) :

"Like as the arrows in the hands of the giant; even so are the young children."

(Compare with this the remarks previously made about "boys.") Because of this significance of the arrow it is intelligible why the Scythian king Ariantes, when he wished to prepare a census, demanded an arrow-head from each man. A similar meaning attaches equally to the lance. Men are descended from the lance, because the ash is the mother of lances. Therefore, the men of the Iron Age are derived from her. The marriage custom to which Ovid alludes ("Comat virgineas hasta recurva comas" -- Fastorum, lib. ii:560) has already been mentioned. Kaineus issued a command that his lance be honored. Pindar relates in the legend of this Kaineus:

"He descended into the depths, splitting the earth with a straight foot." [30]

He is said to have originally been a maiden named Kainis, who, because of her complaisance, was transformed into an invulnerable man by Poseidon. Ovid pictures the battle of the Lapithae with the invulnerable Kaineus; how at last they covered him completely with trees, because they could not otherwise touch him. Ovid says at this place:

"Exitus in dubio est: alii sub inania corpus

Tartara detrusum silvarum mole ferebant,

Abnuit Ampycides: medioque ex aggere fulvis

Vidit avem pennis liquidas exire sub auras." [v]

Roscher considers this bird to be the golden plover (Charadrius pluvialis), which borrows its name from the fact that it lives in the

, a crevice in the earth. By his song he proclaims the approaching rain. Kaineus was changed into this bird.

, a crevice in the earth. By his song he proclaims the approaching rain. Kaineus was changed into this bird.We see again in this little myth the typical constituents of the libido myth: original bisexuality, immortality (invulnerability) through entrance into the mother (splitting the mother with the foot, and to become covered up) and resurrection as a bird of the soul and a bringer of fertility (ascending sun). When this type of hero causes his lance to be worshipped, it probably means that his lance is a valid and equivalent expression of himself.

From our present standpoint, we understand in a new sense that passage in Job, which I mentioned in Chapter IV of the first part of this book:

"He has set me up for his mark.

"His archers compass me round about, he cleaveth my reins asunder, and doth not spare: -- he poureth out my gall upon the ground.

"He breaketh me with breach upon breach: he runneth upon me like a giant." Job xvi: 12-13-14.

Now we understand this symbolism as an expression for the soul torment caused by the onslaught of the unconscious desires. The libido festers in his flesh, a cruel god has taken possession of him and pierced him with his painful libidian projectiles, with thoughts, which overwhelmingly pass through him. (As a dementia praecox patient once said to me during his recovery: "To-day a thought suddenly thrust itself through me.") This same idea is found again in Nietzsche in Zarathustra:

The Magician

Stretched out, shivering

Like one half dead whose feet are warmed,

Shaken alas! by unknown fevers,

Trembling from the icy pointed arrows of frost,

Hunted by Thee, O Thought!

Unutterable! Veiled! Horrible One!

Thou huntsman behind the clouds!

Struck to the ground by thee,

Thou mocking eye that gazeth at me from the dark!

-- Thus do I lie

Bending, writhing, tortured

With all eternal tortures,

Smitten

By thee, crudest huntsman,

Thou unfamiliar God.

Smite deeper!

Smite once more:

Pierce through and rend my heart!

What meaneth this torturing

With blunt-toothed arrows?

Why gazeth thou again,

Never weary of human pain,

With malicious, God-lightning eyes,

Thou wilt not kill,

But torture, torture?

No long-drawn-out explanation is necessary to enable us to recognize in this comparison the old, universal idea of the martyred sacrifice of God, which we have met previously in the Mexican sacrifice of the cross and in the sacrifice of Odin. [31] This same conception faces us in the oft-repeated martyrdom of St. Sebastian, where, in the delicate-glowing flesh of the young god, all the pain of renunciation which has been felt by the artist has been portrayed. An artist always embodies in his artistic work a portion of the mysteries of his time. In a heightened degree the same is true of the principal Christian symbol, the crucified one pierced by the lance, the conception of the man of the Christian era tormented by his wishes, crucified and dying in Christ.

This is not torment which comes from without, which befalls mankind; but that he himself is the hunter, murderer, sacrificer and sacrificial knife is shown us in another of Nietzsche's poems, wherein the apparent dualism is transformed into the soul conflict through the use of the same symbolism:

"Oh, Zarathustra,

Most cruel Nimrod!

Whilom hunter of God

The snare of all virtue,

An arrow of evil!

Now

Hunted by thyself

Thine own prey

Pierced through thyself,

Now

Alone with thee

Twofold in thine own knowledge

Mid a hundred mirrors

False to thyself,

Mid a hundred memories

Uncertain

Ailing with each wound

Shivering with each frost

Caught in thine own snares,

Self knower!

Self hangman!

"Why didst thou strangle thyself

With the noose of thy wisdom?

Why hast thou enticed thyself

Into the Paradise of the old serpent?

Why hast thou crept

Into thyself, thyself? ..."

The deadly arrows do not strike the hero from without, but it is he himself who, in disharmony with himself, hunts, fights and tortures himself. Within himself will has turned against will, libido against libido -- therefore, the poet says, "Pierced through thyself," that is to say, wounded by his own arrow. Because we have discerned that the arrow is a libido symbol, the idea of "penetrating or piercing through" consequently becomes clear to us. It is a phallic act of union with one's self, a sort of self-fertilization (introversion); also a self-violation), a self-murder; therefore, Zarathustra may call himself his own hangman, like Odin, who sacrifices himself to Odin.

The wounding by one's own arrow means, first of all, the state of introversion. What this signifies we .already know the libido sinks into its "own depths" (a well-known comparison of Nietzsche's) and finds there below, in the shadows of the unconscious, the substitute for the upper world, which it has abandoned: the world of memories ("'mid a hundred memories"), the strongest and most influential of which are the early infantile memory pictures. It is the world of the child, this paradise-like state of earliest childhood, from which we are separated by a hard law. In this subterranean kingdom slumber sweet feelings of home and the endless hopes of all that is to be. As Heinrich in the "Sunken Bell," by Gerhart Hauptmann, says, in speaking of his miraculous work:

"There is a song lost and forgotten,

A song of home, a love song of childhood,

Brought up from the depths of the fairy well,

Known to all, but yet unheard."

However, as Mephistopheles says, "The danger is great." These depths are enticing; they are the mother and -- death. When the libido leaves the bright upper world, whether from the decision of the individual or from decreasing life force, then it sinks back into its own depths, into the source from which it has gushed forth, and turns back to that point of cleavage, the umbilicus, through which it once entered into this body. This point of cleavage is called the mother, because from her comes the source of the libido. Therefore, when some great work is to be accomplished, before which weak man recoils, doubtful of his strength, his libido returns to that source -- and this is the dangerous moment, in which the decision takes place between annihilation and new life. If the libido remains arrested in the wonder kingdom of the inner world, [32] then the man has become for the world above a phantom, then he is practically dead or desperately ill. [33] But if the libido succeeds in tearing itself loose and pushing up into the world above, then a miracle appears. This journey to the underworld has been a fountain of youth, and new fertility springs from his apparent death. This train of thought is very beautifully gathered into a Hindoo myth: Once upon a time, Vishnu sank into an ecstasy (introversion) and during this state of sleep bore Brahma, who, enthroned upon the lotus flower, arose from the navel of Vishnu, bringing with him the Vedas, which he diligently read. (Birth of creative thought from introversion.) But through Vishnu's ecstasy a devouring flood came upon the world. (Devouring through introversion, symbolizing the danger of entering into the mother of death.) A demon taking advantage of the danger, stole the Vedas from Brahma and hid them in the depths. (Devouring of the libido.) Brahma roused Vishnu, and the latter, transforming himself into a fish, plunged into the flood, fought with the demon (battle with the dragon), conquered him and recaptured the Vedas. (Treasure obtained with difficulty.)

Self-concentration and the strength derived therefrom correspond to this primitive train of thought. It also explains numerous sacrificial and magic rites which we have already fully discussed. Thus the impregnable Troy falls because the besiegers creep into the belly of a wooden horse; for he alone is a hero who is reborn from the mother, like the sun. But the danger of this venture is shown by the history of Philoctetes, who was the only one in the Trojan expedition who knew the hidden sanctuary of Chryse, where the Argonauts had sacrificed already, and where the Greeks planned to sacrifice in order to assure a safe ending to their undertaking. Chryse was a nymph upon the island of Chryse; according to the account of the scholiasts in Sophocles's "Philoctetes," this nymph loved Philoctetes, and cursed him because he spurned her love. This characteristic projection, which is also met with in the Gilgamesh epic, should be referred back, as suggested, to the repressed incest wish of the son, who is represented through the projection as if the mother had the evil wish, for the refusal of which the son was given over to death. In reality, however, the son becomes mortal by separating himself from the mother. His fear of death, therefore, corresponds to the repressed wish to turn back to the mother, and causes him to believe that the mother threatens or pursues him. The teleological significance of this fear of persecution is evident; it is to keep son and mother apart.

The curse of Chryse is realized in so far that Philoctetes, according to one version, when approaching his altar, injured himself in his foot with one of his own deadly poisonous arrows, or, according to another version [34] (this is better and far more abundantly proven), was bitten in his foot by a poisonous serpent. [35] From then on he is ailing. [36]

This very typical wound, which also destroyed Re, is described in the following manner in an Egyptian hymn:

"The ancient of the Gods moved his mouth,

He cast his saliva upon the earth,

And what he spat, fell upon the ground.

With her hands Isis kneaded that and the soil

Which was about it, together:

From that she created a venerable worm,

And made him like a spear.

She did not twist him living around her face,

But threw him coiled upon the path,

Upon which the great God wandered at ease

Through all his lands.

"The venerable God stepped forth radiantly,

The gods who served Pharaoh accompanied him,

And he proceeded as every day.

Then the venerable worm stung him. . . .

The divine God opened his mouth

And the voice of his majesty echoed even to the sky.

And the gods exclaimed: Behold!

Thereupon he could not answer,

His jaws chattered,

All his limbs trembled

And the poison gripped his flesh,

As the Nile seizes upon the land."

In this hymn Egypt has again preserved for us a primitive conception of the serpent's sting. The aging of the autumn sun as an image of human senility is symbolically traced back to the mother through the poisoning by the serpent. The mother is reproached, because her malice causes the death of the sun-god. The serpent, the primitive symbol of fear, [37] illustrates the repressed tendency to turn back to the mother, because the only possibility of security from death is possessed by the mother, as the source of life.

Accordingly, only the mother can cure him, sick unto death, and, therefore, the hymn goes on to depict how the gods were assembled to take counsel:

"And Isis came with her wisdom :

Her mouth is full of the breath of life,

Her words banish sorrow,

And her speech animates those who no longer breathe.

She said: 'What is that; what is that, divine father?

Behold, a worm has brought you sorrow --'

"'Tell me thy name, divine father,

Because the man remains alive, who is called by his name.'"

Whereupon Re replied:

"' I am he, who created heaven and earth, and piled up the hills,

And created all beings thereon.

I am he, who made the water and caused the great flood,

Who produced the bull of his mother,

Who is the procreator,' etc.

"The poison did not depart, it went further,

The great God was not cured.

Then said Isis to Re:

'Thine is not the name thou hast told me.

Tell me true that the poison may leave thee,

For he whose name is spoken will live.'"

Finally Re decides to speak his true name. He is approximately healed (imperfect composition of Osiris); but he has lost his power, and finally he retreats to the heavenly cow.

The poisonous worm is, if one may speak in this way, a "negative" phallus, a deadly, not an animating, form of libido; therefore, a wish for death, instead of a wish for life. The "true name" is soul and magic power; hence a symbol of libido. What Isis demands is the re-transference of the libido to the mother goddess. This request is fulfilled literally, for the aged god turns back to the divine cow, the symbol of the mother. [38] This symbolism is clear from our previous explanations. The onward urging, living libido which rules the consciousness of the son, demands separation from the mother. The longing of the child for the mother is a hindrance on the path to this, taking the form of a psychologic resistance, which is expressed empirically in the neurosis by all manners of fears, that is to say, the fear of life. The more a person withdraws from adaptation to reality, and falls into slothful inactivity, the greater becomes his anxiety (cum grano salis), which everywhere besets him at each point as a hindrance upon his path. The fear springs from the mother, that is to say, from the longing to go back to the mother, which is opposed to the adaptation to reality. This is the way in which the mother has become apparently the malicious pursuer. Naturally, it is not the actual mother, although the actual mother, with the abnormal tenderness with which she sometimes pursues her child, even into adult years, may gravely injure it through a willful prolonging of the infantile state in the child. It is rather the mother-imago, which becomes the Lamia. The mother-imago, however, possesses its power solely and exclusively from the son's tendency not only to look and to work forwards, but also to glance backwards to the pampering sweetness of childhood, to that glorious state of irresponsibility and security with which the protecting mother-care once surrounded him. [39]

The retrospective longing acts like a paralyzing poison upon the energy and enterprise; so that it may well be compared to a poisonous serpent which lies across our path. Apparently, it is a hostile demon which robs us of energy, but, in reality, it is the individual unconscious, the retrogressive tendency of which begins to overcome the conscious forward striving. The cause of this can be, for example, the natural aging which weakens the energy, or it may be great external difficulties, which cause man to break down and become a child again, or it may be, and this is probably the most frequent cause, the woman who enslaves the man, so that he can no longer free himself, and becomes a child again. [40] It may be of significance also that Isis, as sister-wife of the sun-god, creates the poisonous animal from the spittle of the god, which is perhaps a substitute for sperma, and, therefore, is a symbol of libido. She creates the animal from the libido of the god; that means she receives his power, making him weak and dependent, so that by this means she assumes the dominating role of the mother. (Mother transference to the wife.) This part is preserved in the legend of Samson, in the role of Delilah, who cut off Samson's hair, the sun's rays, thus robbing him of his strength. [41] Any weakening of the adult man strengthens the wishes of the unconscious; therefore, the decrease of strength appears directly as the backward striving towards the mother.

There is still to be considered one more source of the reanimation of the mother-imago. We have already met it in the discussion of the mother scene in "Faust," that is to say, the willed introversion of a creative mind, which, retreating before its own problem and inwardly collecting its forces, dips at least for a moment into the source of life, in order there to wrest a little more strength from the mother for the completion of its work. It is a mother-child play with one's self, in which lies much weak self-admiration and self-adulation ("Among a hundred mirrors" -- Nietzsche); a Narcissus state, a strange spectacle, perhaps, for profane eyes. The separation from the mother-imago, the birth out of one's self, reconciles all conflicts through the sufferings. This is probably meant by Nietzsche's verse:

"Why hast thou enticed thyself

Into the Paradise of the old serpent?

Why hast thou crept

Into thyself, thyself? . . .

"A sick man now

Sick of a serpent's poison,"

A captive now

Whom the hardest destiny befell

In thine own pit;

Bowed down as thou workest

Encaved within thyself,

Burrowing into thyself,

Helpless,

Stiff,

A corpse.

Overwhelmed with a hundred burdens,

Overburdened by thyself.

A wise man,

A self-knower,

The wise Zarathustra;

Thou soughtest the heaviest burden

And foundest thou thyself. ..."

The symbolism of this speech is of the greatest richness. He is buried in the depths of self, as if in the earth; really a dead man who has turned back to mother earth; [43] a Kaineus "piled with a hundred burdens" and pressed down to death; the one who groaning bears the heavy burden of his own libido, of that libido which draws him back to the mother. Who does not think of the Taurophoria of Mithra, who took his bull (according to the Egyptian hymn, "the bull of his mother"), that is, his love for his mother, the heaviest burden upon his back, and with that entered upon the painful course of the so-called Transitus! [44] This path of passion led to the cave, in which the bull was sacrificed. Christ, too, had to bear the cross, [45] the symbol of his love for the mother, and he carried it to the place of sacrifice where the lamb was slain in the form of the God, the infantile man, a "self-executioner," and then to burial in the subterranean sepulchre. [46]

That which in Nietzsche appears as a poetical figure of speech is really a primitive myth. It is as if the poet still possessed a dim idea or capacity to feel and reactivate those imperishable phantoms of long-past worlds of thought in the words of our present-day speech and in the images which crowd themselves into his phantasy. Hauptmann also says: "Poetic rendering is that which allows the echo of the primitive word to resound through the form." [47]

***

The sacrifice, with its mysterious and manifold meaning, which is rather hinted at than expressed, passes unrecognized in the unconscious of our author. The arrow is not shot, the hero Chiwantopel is not yet fatally poisoned and ready for death through self-sacrifice. We now can say, according to the preceding material, this sacrifice means renouncing the mother, that is to say, renunciation of all bonds and limitations which the soul has taken with it from the period of childhood into the adult life. From various hints of Miss Miller's it appears that at the time of these phantasies she was still living in the circle of the family, evidently at an age which was in urgent need of independence. That is to say, man does not live very long in the infantile environment or in the bosom of his family without real danger to his mental health. Life calls him forth to independence, and he who gives no heed to this hard call because of childish indolence and fear is threatened by a neurosis, and once the neurosis has broken out it becomes more and more a valid reason to escape the battle with life and to remain for all time in the morally poisoned infantile atmosphere.

The phantasy of the arrow-wound belongs in this struggle for personal independence. The thought of this resolution has not yet penetrated the dreamer. On the contrary, she rather repudiates it. After all the preceding, it is evident that the symbolism of the arrow-wound through direct translation must be taken as a coitus symbol. The "Occide moriturus" attains by this means the sexual significance belonging to it. Chiwantopel naturally represents the dreamer. But nothing is attained and nothing is understood through one's reduction to the coarse sexual, because it is a commonplace that the unconscious shelters coitus wishes, the discovery of which signifies nothing further. The coitus wish under this aspect is really a symbol for the individual demonstration of the libido separated from the parents, of the conquest of an independent life. This step towards a new life means, at the same time, the death of the past life. [48] Therefore, Chiwantopel is the infantile hero [49] (the son, the child, the lamb, the fish) who is still enchained by the fetters of childhood and who has to die as a symbol of the incestuous libido, and with that sever the retrogressive bond. For the entire libido is demanded for the battle of life, and there can be no remaining behind. The dreamer cannot yet come to this decision, which will tear aside all the sentimental connections with father and mother, and yet it must be made in order to follow the call of the individual destiny.

_______________

Notes:

i. Come, O Dionysus, in thy temple of Elis, come with the Graces into thy holy temple: come in sacred frenzy with the bull's foot.

ii. The present time is indicated by the head of the lion -- because his condition is strong and impetuous.

iii. Time is thought by the wickedest people to be a divinity who deprives willing people of essential being; by good men it is considered to be the Cause of the things of the world, but to the wisest and best it does not seem time, but God.

iv. "Fight," she said, "and fight bravely, for I will not give away an inch nor turn my back. Face to face, come on if you are a man! Strike home, do your worst and die! The battle this day is without quarter . . . till, weary in body and mind, we lie powerless and gasping for breath in each other's arms."

v. The result is doubtful: the body borne down by the weight of the forest is carried into empty Tartaros: Ampycides denies this: from out of the midst of the mass, he sees a bird with tawny feathers issue into the liquid air.

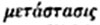

, a son, our hero.

, a son, our hero.

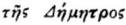

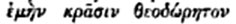

equals libido, also Mother libido.) He was identified with Dionysus, especially with the Thracian Dionysus-Zagreus, of whom a typical fate of rebirth was related. Hera had goaded the Titans against Zagreus, who, assuming many forms, sought to escape them, until they finally took him when he had taken on the form of a bull. In this form he was killed (Mithra sacrifice) and dismembered, and the pieces were thrown into a cauldron; but Zeus killed the Titans by lightning, and swallowed the still-throbbing heart of Zagreus. Through this act he gave him existence once more, and Zagreus as Iakchos again came forth.

equals libido, also Mother libido.) He was identified with Dionysus, especially with the Thracian Dionysus-Zagreus, of whom a typical fate of rebirth was related. Hera had goaded the Titans against Zagreus, who, assuming many forms, sought to escape them, until they finally took him when he had taken on the form of a bull. In this form he was killed (Mithra sacrifice) and dismembered, and the pieces were thrown into a cauldron; but Zeus killed the Titans by lightning, and swallowed the still-throbbing heart of Zagreus. Through this act he gave him existence once more, and Zagreus as Iakchos again came forth. , mystica vannus lacchi.) The Orphic legend [34] relates that lakchos was brought up by Persephone, when, after three years' slumber in the

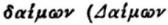

, mystica vannus lacchi.) The Orphic legend [34] relates that lakchos was brought up by Persephone, when, after three years' slumber in the  . [iii] Lukian lets the magician Mithrobarzanes

. [iii] Lukian lets the magician Mithrobarzanes  [iv] descend into the bowels of the earth. According to the testimony of Moses of the Koran, the sister Fire and the brother Spring were worshipped in Armenia in a cave. Julian gave an account from the Attis legend of a

[iv] descend into the bowels of the earth. According to the testimony of Moses of the Koran, the sister Fire and the brother Spring were worshipped in Armenia in a cave. Julian gave an account from the Attis legend of a  [v] from whence Cybele brings up her son lover, that is to say, gives birth to him. [38] The cave of Christ's birth, in Bethlehem ('House of Bread'), is said to have been an Attis spelaeum.

[v] from whence Cybele brings up her son lover, that is to say, gives birth to him. [38] The cave of Christ's birth, in Bethlehem ('House of Bread'), is said to have been an Attis spelaeum. . [vi] Clemens observes that the symbol of the Sabazios mysteries is

. [vi] Clemens observes that the symbol of the Sabazios mysteries is

[vii]

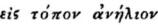

[vii] [ix] which indicates that the god enters into man as if through the female genitals. [43] According to the testimony of Hippolytus, the hierophant in the mystery exclaimed

[ix] which indicates that the god enters into man as if through the female genitals. [43] According to the testimony of Hippolytus, the hierophant in the mystery exclaimed  (the revered one has brought forth a holy boy, Brimos from Brimo). This Christmas gospel, "Unto us a son is born," is illustrated especially through the tradition [44] that the Athenians "secretly show to the partakers in the Epoptia, the great and wonderful and most perfect Epoptic mystery, a mown stalk of wheat." [45]

(the revered one has brought forth a holy boy, Brimos from Brimo). This Christmas gospel, "Unto us a son is born," is illustrated especially through the tradition [44] that the Athenians "secretly show to the partakers in the Epoptia, the great and wonderful and most perfect Epoptic mystery, a mown stalk of wheat." [45]

.'" [x]

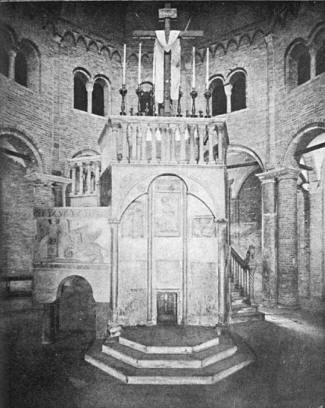

.'" [x] " (chalice), covered with a cloth. The covering of the head signifies death. The mystic dies, figuratively, like the seed corn, grows again and comes to the corn harvest. Proclus relates that the mystics were buried up to their necks. The Christian church as a place of religious ceremony is really nothing but the grave of a hero (catacombs). The believer descends into the grave, in order to rise from the dead with the hero. That the meaning underlying the church is that of the mother's womb can scarcely be doubted. The symbols of Mass are so distinct that the mythology of the sacred act peeps out everywhere. It is the magic charm of rebirth. The veneration of the Holy Sepulchre is most plain in this respect. A striking example is the Holy Sepulchre of St. Stefano in Bologna. The church itself, a very old polygonal building, consists of the remains of a temple to Isis. The interior contains an artificial spelaeum, a so-called Holy Sepulchre, into which one creeps through a very little door. After a long sojourn, the believer reappears reborn from this mother's womb. An Etruscan ossuarium in the archaeological museum in Florence is at the same time a statue of Matuta, the goddess of death; the clay figure of the goddess is hollowed within as a receptacle for the ashes. The representations indicate that Matuta is the mother. Her chair is adorned with sphinxes, as a fitting symbol for the mother of death.

" (chalice), covered with a cloth. The covering of the head signifies death. The mystic dies, figuratively, like the seed corn, grows again and comes to the corn harvest. Proclus relates that the mystics were buried up to their necks. The Christian church as a place of religious ceremony is really nothing but the grave of a hero (catacombs). The believer descends into the grave, in order to rise from the dead with the hero. That the meaning underlying the church is that of the mother's womb can scarcely be doubted. The symbols of Mass are so distinct that the mythology of the sacred act peeps out everywhere. It is the magic charm of rebirth. The veneration of the Holy Sepulchre is most plain in this respect. A striking example is the Holy Sepulchre of St. Stefano in Bologna. The church itself, a very old polygonal building, consists of the remains of a temple to Isis. The interior contains an artificial spelaeum, a so-called Holy Sepulchre, into which one creeps through a very little door. After a long sojourn, the believer reappears reborn from this mother's womb. An Etruscan ossuarium in the archaeological museum in Florence is at the same time a statue of Matuta, the goddess of death; the clay figure of the goddess is hollowed within as a receptacle for the ashes. The representations indicate that Matuta is the mother. Her chair is adorned with sphinxes, as a fitting symbol for the mother of death.

= "to hide, to conceal." Also hut (hut, to guard; English, hide), Germanic root hud, from Indo-Germanic kuth (questionable), to Greek

= "to hide, to conceal." Also hut (hut, to guard; English, hide), Germanic root hud, from Indo-Germanic kuth (questionable), to Greek  and

and  "cavity," feminine genitals. Prellwitz, [70] too, traces Gothic huzd, Anglo-Saxon hyde, English hide and hoard, to Greek

"cavity," feminine genitals. Prellwitz, [70] too, traces Gothic huzd, Anglo-Saxon hyde, English hide and hoard, to Greek  . Whitley Stokes traces English hide, Anglo-Saxon hydan, New High German Hutte, Latin cudo = helmet; Sanskrit kuhara (cave?) to primitive Celtic koudo = concealment; Latin, occultatio.

. Whitley Stokes traces English hide, Anglo-Saxon hydan, New High German Hutte, Latin cudo = helmet; Sanskrit kuhara (cave?) to primitive Celtic koudo = concealment; Latin, occultatio.

[xi] One sacrifices the honey cake to the mother, so that she may spare one from death. Thus every year in Rome a gold sacrifice was thrown into the lacus Curtius, into the former fissure in the earth, which could only be closed through the sacrificial death of Curtius. He was the typical hero, who has journeyed into the underworld, in order to conquer the danger threatening the Roman state from the opening of the abyss. (Kaineus, Amphiaraos.) In the Amphiaraion of Oropos those healed through the temple incubation threw their gifts of gold into the sacred well, of which Pausanias says:

[xi] One sacrifices the honey cake to the mother, so that she may spare one from death. Thus every year in Rome a gold sacrifice was thrown into the lacus Curtius, into the former fissure in the earth, which could only be closed through the sacrificial death of Curtius. He was the typical hero, who has journeyed into the underworld, in order to conquer the danger threatening the Roman state from the opening of the abyss. (Kaineus, Amphiaraos.) In the Amphiaraion of Oropos those healed through the temple incubation threw their gifts of gold into the sacred well, of which Pausanias says:

." [xiv]

." [xiv] , [xv] was broken off. This rod protected the purity of virgins, and caused any one who touched the plant to become insane. We recognize in this the motive of the sacred tree, which, as mother, must not be touched, an act which only an insane person would commit. Hecate, as nightmare, appears in the form of Empusa, in a vampire role, or as Lamia, as devourer of men; perhaps, also, in that more beautiful guise, "The Bride of Corinth." She is the mother of all charms and witches, the patron of Medea, because the power of the "terrible mother" is magical and irresistible (working upward from the unconscious). In Greek syncretism, she plays a very significant role. She is confused with Artemis, who also has the surname

, [xv] was broken off. This rod protected the purity of virgins, and caused any one who touched the plant to become insane. We recognize in this the motive of the sacred tree, which, as mother, must not be touched, an act which only an insane person would commit. Hecate, as nightmare, appears in the form of Empusa, in a vampire role, or as Lamia, as devourer of men; perhaps, also, in that more beautiful guise, "The Bride of Corinth." She is the mother of all charms and witches, the patron of Medea, because the power of the "terrible mother" is magical and irresistible (working upward from the unconscious). In Greek syncretism, she plays a very significant role. She is confused with Artemis, who also has the surname  , [xvi] "the one striking at a distance" or "striking according to her will," in which we recognize again her superior power. Artemis is the huntress, with hounds, and so Hecate, through confusion with her, becomes

, [xvi] "the one striking at a distance" or "striking according to her will," in which we recognize again her superior power. Artemis is the huntress, with hounds, and so Hecate, through confusion with her, becomes  , the wild nocturnal huntress. (God, as huntsman, see above.) She has her name in common with Apollo,

, the wild nocturnal huntress. (God, as huntsman, see above.) She has her name in common with Apollo,

. [xvii] From the standpoint of the libido theory, this connection is easily understandable, because Apollo merely symbolizes the more positive side of the same amount of libido. The confusion of Hecate with Brimo as subterranean mother is understandable; also with Persephone and Rhea, the primitive all-mother. Intelligible through the maternal significance is the confusion with Ilithyia, the midwife. Hecate is also the direct goddess of births,

. [xvii] From the standpoint of the libido theory, this connection is easily understandable, because Apollo merely symbolizes the more positive side of the same amount of libido. The confusion of Hecate with Brimo as subterranean mother is understandable; also with Persephone and Rhea, the primitive all-mother. Intelligible through the maternal significance is the confusion with Ilithyia, the midwife. Hecate is also the direct goddess of births,  [xviii] the multiplier of cattle, and goddess of marriage. Hecate, orphically, occupies the centre of the world as Aphrodite and Gaia, even as the world soul in general. On a carved gem [86] she is represented carrying the cross on her head. The beam on which the criminal was scourged is called

[xviii] the multiplier of cattle, and goddess of marriage. Hecate, orphically, occupies the centre of the world as Aphrodite and Gaia, even as the world soul in general. On a carved gem [86] she is represented carrying the cross on her head. The beam on which the criminal was scourged is called  . [xix] To her, as to the Roman Trivia, the triple roads, or Scheideweg, "forked road," or crossways were dedicated. And where roads branch off or unite sacrifices of dogs were brought her; there the bodies of the executed were thrown; the sacrifice occurs at the point of crossing. Etymologically, scheide, "sheath"; for example, sword-sheath, sheath for water-shed and sheath for vagina, is identical with scheiden, "to split," or "to separate." The meaning of a sacrifice at this place would, therefore, be as follows: to offer something to the mother at the place of junction or at the fissure. (Compare the sacrifice to the chthonic gods in the abyss.) The Temenos of Ge, the abyss and the well, are easily understood as the gates of life and death, [87] "past which every one gladly creeps" (Faust), and sacrifices there his obolus or his

. [xix] To her, as to the Roman Trivia, the triple roads, or Scheideweg, "forked road," or crossways were dedicated. And where roads branch off or unite sacrifices of dogs were brought her; there the bodies of the executed were thrown; the sacrifice occurs at the point of crossing. Etymologically, scheide, "sheath"; for example, sword-sheath, sheath for water-shed and sheath for vagina, is identical with scheiden, "to split," or "to separate." The meaning of a sacrifice at this place would, therefore, be as follows: to offer something to the mother at the place of junction or at the fissure. (Compare the sacrifice to the chthonic gods in the abyss.) The Temenos of Ge, the abyss and the well, are easily understood as the gates of life and death, [87] "past which every one gladly creeps" (Faust), and sacrifices there his obolus or his  , [xx] instead of his body, just as Hercules soothes Cerberus with the honey cakes. (Compare with this the mythical significance of the dog!) Thus the crevice at Delphi, with the spring, Castalia, was the seat of the chthonic dragon, Python, who was conquered by the sun-hero, Apollo. (Python, incited by Hera, pursued Leta, pregnant with Apollo; but she, on the floating island of Delos [nocturnal journey on the sea], gave birth to her child, who later slew the Python; that is to say, conquered in it the spirit mother.) In Hierapolis (Edessa) the temple was erected above the crevice through which the flood had poured out, and in Jerusalem the foundation stone of the temple covered the great abyss, [88] just as Christian churches are frequently built over caves, grottoes, wells, etc. In the Mithra grotto, [89] and all the other sacred caves up to the Christian catacombs, which owe their significance not to the legendary persecutions but to the worship of the dead, [90] we come across the same fundamental motive. The burial of the dead in a holy place (in the "garden of the dead," in cloisters, crypts, etc.) is restitution to the mother, with the certain hope of resurrection by which such burial is rightfully rewarded. The animal of death which dwells in the cave had to be soothed in early times through human sacrifices; later with natural gifts. [91] Therefore, the Attic custom gives to the dead the

, [xx] instead of his body, just as Hercules soothes Cerberus with the honey cakes. (Compare with this the mythical significance of the dog!) Thus the crevice at Delphi, with the spring, Castalia, was the seat of the chthonic dragon, Python, who was conquered by the sun-hero, Apollo. (Python, incited by Hera, pursued Leta, pregnant with Apollo; but she, on the floating island of Delos [nocturnal journey on the sea], gave birth to her child, who later slew the Python; that is to say, conquered in it the spirit mother.) In Hierapolis (Edessa) the temple was erected above the crevice through which the flood had poured out, and in Jerusalem the foundation stone of the temple covered the great abyss, [88] just as Christian churches are frequently built over caves, grottoes, wells, etc. In the Mithra grotto, [89] and all the other sacred caves up to the Christian catacombs, which owe their significance not to the legendary persecutions but to the worship of the dead, [90] we come across the same fundamental motive. The burial of the dead in a holy place (in the "garden of the dead," in cloisters, crypts, etc.) is restitution to the mother, with the certain hope of resurrection by which such burial is rightfully rewarded. The animal of death which dwells in the cave had to be soothed in early times through human sacrifices; later with natural gifts. [91] Therefore, the Attic custom gives to the dead the  , to pacify the dog of hell, the three-headed monster at the gate of the underworld. A more recent elaboration of the natural gifts seems to be the obolus for Charon, who is, therefore, designated by Rohde as the second Cerberus, corresponding to the Egyptian dog-faced god Anubis. [92] Dog and serpent of the underworld (Dragon) are likewise identical. In the tragedies, the Erinnyes are serpents as well as dogs; the serpents Tychon and Echidna are parents of the serpents -- Hydra, the dragon of the Hesperides, and Gorgo; and of the dogs, Cerberus, Orthrus, Scylla. [93] Serpents and dogs are also protectors of the treasure. The chthonic god was probably always a serpent dwelling in a cave, and was fed with

, to pacify the dog of hell, the three-headed monster at the gate of the underworld. A more recent elaboration of the natural gifts seems to be the obolus for Charon, who is, therefore, designated by Rohde as the second Cerberus, corresponding to the Egyptian dog-faced god Anubis. [92] Dog and serpent of the underworld (Dragon) are likewise identical. In the tragedies, the Erinnyes are serpents as well as dogs; the serpents Tychon and Echidna are parents of the serpents -- Hydra, the dragon of the Hesperides, and Gorgo; and of the dogs, Cerberus, Orthrus, Scylla. [93] Serpents and dogs are also protectors of the treasure. The chthonic god was probably always a serpent dwelling in a cave, and was fed with  , belonging to

, belonging to  , means the innermost womb of the earth (Hades); , that Kluge adds, is of similar meaning, cavity or womb. Prellwitz does not mention this connection. Fick, [96] however, compares New High German hort, Gothic huzd, to Armenian kust, "abdomen"; Church Slavonian cista, Vedic kostha = abdomen, from the Indo-Germanic root koustho -s = viscera, lower abdomen, room, store-room. Prellwitz compares

, means the innermost womb of the earth (Hades); , that Kluge adds, is of similar meaning, cavity or womb. Prellwitz does not mention this connection. Fick, [96] however, compares New High German hort, Gothic huzd, to Armenian kust, "abdomen"; Church Slavonian cista, Vedic kostha = abdomen, from the Indo-Germanic root koustho -s = viscera, lower abdomen, room, store-room. Prellwitz compares  = urinary bladder, bag, purse ; Sanskrit kustha-s = cavity of the loins; then

= urinary bladder, bag, purse ; Sanskrit kustha-s = cavity of the loins; then  = cavity, vault;

= cavity, vault;  = little chest, from

= little chest, from  = I am pregnant. Here, from

= I am pregnant. Here, from  = cave,

= cave,  = hole,

= hole,  = cup,

= cup,  = depression under the eye,

= depression under the eye,  = swelling, wave, billow,

= swelling, wave, billow,  = power, force,

= power, force,  = lord, Old Iranian caur, cur = hero; Sanskrit cura -s = strong, hero. The fundamental Indo-Germanic roots [97] are kevo = to swell, to be strong. From that the above-mentioned

= lord, Old Iranian caur, cur = hero; Sanskrit cura -s = strong, hero. The fundamental Indo-Germanic roots [97] are kevo = to swell, to be strong. From that the above-mentioned  and Latin cavus = hollow, vaulted, cavity, hole; cavea = cavity, enclosure, cage, scene and assembly; caulae = cavity, opening, enclosure, stall [98]; kueyo = swell; participle, kueyonts = swelling; en-kueyonts = pregnant,

and Latin cavus = hollow, vaulted, cavity, hole; cavea = cavity, enclosure, cage, scene and assembly; caulae = cavity, opening, enclosure, stall [98]; kueyo = swell; participle, kueyonts = swelling; en-kueyonts = pregnant,  = Latin inciens = pregnant; compare Sanskrit vi-cva- yan = swelling; kuro -s (kevaro-s), strong, powerful hero.

= Latin inciens = pregnant; compare Sanskrit vi-cva- yan = swelling; kuro -s (kevaro-s), strong, powerful hero.

, those who come from the same womb. We who are reborn again from the mother are all heroes together with Christ, and enjoy immortal food. As with the Jews, so too with the Christians, there is imminent danger of unworthy partaking, for this mystery, which is very closely related psychologically with the subterranean Hierosgamos of Eleusis, involves a mysterious union of man in a spiritual sense, [102] which was constantly misunderstood by the profane and was retranslated into his language, where mystery is equivalent to orgy and secrecy to vice. [103] A very interesting blasphemer and sectarian of the beginning of the nineteenth century named Unternahrer has made the following comment on the last supper:

, those who come from the same womb. We who are reborn again from the mother are all heroes together with Christ, and enjoy immortal food. As with the Jews, so too with the Christians, there is imminent danger of unworthy partaking, for this mystery, which is very closely related psychologically with the subterranean Hierosgamos of Eleusis, involves a mysterious union of man in a spiritual sense, [102] which was constantly misunderstood by the profane and was retranslated into his language, where mystery is equivalent to orgy and secrecy to vice. [103] A very interesting blasphemer and sectarian of the beginning of the nineteenth century named Unternahrer has made the following comment on the last supper:

. [xxiii] We have already observed that the place of transformation is really the uterus. Absorption in one's self (introversion) is an entrance into one's own uterus, and also at the same time asceticism. In the philosophy of the Brahmans the world arose from this activity; among the post-Christian Gnostics it produced the revival and spiritual rebirth of the individual, who was born into a new spiritual world. The Hindoo philosophy is considerably more daring and logical, and assumes that creation results from introversion in general, as in the wonderful hymn of Rigveda, 10, 29, it is said:

. [xxiii] We have already observed that the place of transformation is really the uterus. Absorption in one's self (introversion) is an entrance into one's own uterus, and also at the same time asceticism. In the philosophy of the Brahmans the world arose from this activity; among the post-Christian Gnostics it produced the revival and spiritual rebirth of the individual, who was born into a new spiritual world. The Hindoo philosophy is considerably more daring and logical, and assumes that creation results from introversion in general, as in the wonderful hymn of Rigveda, 10, 29, it is said:

[130] [xxiv].

[130] [xxiv].

.

. belongs to

belongs to  = staff;

= staff;  = storm-wind; Latin scapus = shaft, stock, scapula, shoulder; Old High German Scaft = spear, lance. [13] We meet once more in this compilation those connections which are already well known to us: Sun-phallus as tube of the winds, lance and shoulder-blade.

= storm-wind; Latin scapus = shaft, stock, scapula, shoulder; Old High German Scaft = spear, lance. [13] We meet once more in this compilation those connections which are already well known to us: Sun-phallus as tube of the winds, lance and shoulder-blade. [ i] and his destiny does not lie in his own hands; his adventures,

[ i] and his destiny does not lie in his own hands; his adventures,  , [ii] fall from the stars. His unconscious incestuous libido, which thus is applied in its most primitive form, fixes the man, as regards his love type, in a corresponding primitive stage, the stage of ungovernableness and surrender to the emotions. Such was the psychologic situation of the passing antiquity, and the Redeemer and Physician of that time was he who endeavored to educate man to the sublimation of the incestuous libido. [15] The destruction of slavery was the necessary condition of that sublimation, for antiquity had not yet recognized the duty of work and work as a duty, as a social need of fundamental importance. Slave labor was compulsory work, the counterpart of the equally disastrous compulsion of the libido of the privileged. It was only the obligation of the individual to work which made possible in the long run that regular "drainage" of the unconscious, which was inundated by the continual regression of the libido. Indolence is the beginning of all vice, because in a condition of slothful dreaming the libido has abundant opportunity for sinking into itself, in order to create compulsory obligations by means of regressively reanimated incestuous bonds. The best liberation is through regular work. [16] Work, however, is salvation only when it is a free act, and has in itself nothing of infantile compulsion. In this respect, religious ceremony appears in a high degree as organized inactivity, and at the same time as the forerunner of modern work.