by admin » Fri Dec 04, 2020 8:19 am

by admin » Fri Dec 04, 2020 8:19 am

Part 2 of 2

NARUD.

Shall not then the souls of good men receive rewards? Nor the souls of the bad meet with punishment?

BRIMHA.

The souls of men are distinguished from those of other animals; for the first are endued with reason, [Upiman.] and with a consciousness of right and wrong. If therefore man shall adhere to the first, as far as his powers shall extend, his soul, when disengaged from the body by death, shall be absorbed into the divine essence, and shall never more re-animate flesh. But the souls of those who do evil, [Mund.] are not, at death, disengaged from all the elements. They are immediately clothed with a body of fire, air, and akash, in which they are, for a time, punished in hell. [Nirick. The Hindoos reckon above eighty kinds of hells, each proportioned to the degree of the wickedness of the persons punished there. The Brahmins have no idea that all the sins that a man can commit in the short period of his life, can deserve eternal punishment; nor that all the virtues he can exercise, can merit perpetual felicity in heaven.] After the season of their grief is over, they re-animate other bodies; but till they shall arrive at a state of purity, they can never be absorbed into God.

NARUD.

What is the nature of that absorbed state [Muchti.] which the souls of good men enjoy after death?

BRIMHA.

It is a participation of the divine nature, where all passions are utterly unknown, and where consciousness is lost in bliss. [It is somewhat surprising, that a state of unconsciousness, which in fact is the same with annihilation, should be esteemed by the Hindoos as the supreme good; yet so it is, that they always represent the absorbed state, as a situation of perfect insensibility, equally destitute of pleasure and of pain. But Brimha seems here to imply, that it is a kind of delirium of joy.]

NARUD.

Thou sayst, O Father! that unless the soul is perfectly pure, it cannot be absorbed into God: Now, as the actions of the generality of men are partly good, and partly bad, whither are their spirits sent immediately after death?

BRIMHA.

They must atone for their crimes in hell, where they must remain for a space proportioned to the degree of their iniquities; then they rise to heaven to be rewarded for a time for their virtues; and from thence they will return to the world, to reanimate other bodies.

NARUD.

What is time? [Kaal. It may not be improper, in this place, to say something concerning the Hindoo method of computing time. Their least subdivision of time is, the Nemish or twinkling of an eye. Three Nemish's make one Kaan, fifty Kaan one Ligger, ten Liggers one Dind, two Dinds one Gurry, equal to forty-five of our minutes; four Gurries one Pâr, eight Pârs one Dien or day, fifteen Diens one Packa, two Packas one Måsh, four Måshes one Ribbi, three Ribbis one Aioon or year, which only consists of 360 days, but when the odd days, hours, and minutes, wanting of a solar year, amount to one revolution of the moon, an additional month is made to that year to adjust the calendar. A year of 360 days, they reckon but one day to the Dewtas or host of heaven; and they say, that twelve thousand of those planetary years, make one revolution of the four Jugs or periods, into which they divide the ages of the world. The Sittoh Jug, or age of truth, contained, according to them, four thousand planetary years. The Treta Jug, or age of three, contained three thousand years. The Duapur Jug, or age of two, contained two thousand; and the Kallé Jug, or age of pollution, consists of only one thousand. To these they add two other periods, between the dissolution and renovation of the world, which they call Sundeh, and Sundass, each of a thousand planetary years; so that from one Maperly, or great dissolution of all things, to another, there are 3,720,000 of our years.]

BRIMHA.

Time existed from all eternity with God; but it can only be estimated since motion was produced, and only be conceived by the mind, from its own constant progress.

NARUD.

How long shall this world remain?

BRIMHA.

Until the four jugs shall have revolved. Then Rudder [The same with Shibah, the destroying quality of God.] with the ten spirits of dissolution shall roll a comet under the moon, that shall involve all things in fire, and reduce the world into ashes. God shall then exist alone, for matter will be totally annihilated. [Nisht.]

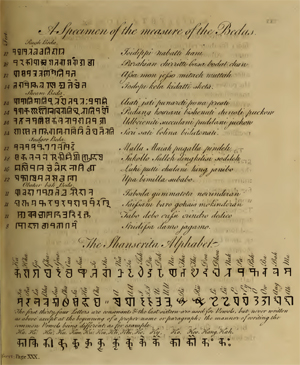

Here ends the first chapter of the Bedang. The second treats of Providence and free will; a subject so abstruse, that it was impossible to understand it, without a complete knowledge of the Shanscrita. The author of the Bedang, thinking perhaps, that the philosophical catechism which we have translated above, was too pure for narrow and superstitious minds, has inserted into his work, a strange allegorical account of the creation, for the purposes of vulgar theology. In this tale, the attributes of God, the human passions and faculties of the mind, are personified, and introduced upon the stage. As this allegory may afford matter of some curiosity to the public, we shall here translate it.

“BRIMHA existed from all eternity, in a form of infinite dimensions. When it pleased him to create the world, he said, Rise up, O Brimha. [The wisdom of God.] Immediately a spirit of the colour of flame issued from his navel, having four heads and four hands. Brimha gazing round, and seeing nothing but the immense image, out of which he had proceeded, he travelled a thousand years, to endeavour to comprehend its dimensions. But after all his toil, he found himself as much at a loss as before.

“Lost in amazement, Brimha gave over his journey. He fell prostrate and praised what he saw with his four mouths. The almighty, then, with a voice like ten thousand thunders, was pleased to say: Thou hast done well, O Brimha, for thou canst not comprehend me! -- Go and create the world! -- How can I create it? -- Ask of me, and power shall be given unto thee. -- O God, said Brimha, thou art almighty in power! --

“Brimha forthwith perceived the idea of things, as if floating before his eyes. He said, LET THEM BE, and all that he saw became real before him. Then fear struck the frame of Brimha, lest those things should be annihilated. O immortal Brihm! he cried, who shall preserve those things which I behold ? In the instant a spirit of a blue colour issued from Brimba's mouth, and said aloud, I WILL. Then shall thy name be Bishen, [The providence of God.] because thou hast undertaken to preserve all things.

“Brimha then commanded Bishen to go and create all animals, with vegetables for their subsistence, to possess that earth which he himself had made. Bishen forthwith created all manner of beasts, fish, fowl, insects, and reptiles. Trees and grass rose also beneath his hands, for Brimba had invested him with power. But man was still wanting to rule the whole: and Brimha commanded Bishen to form him. Bishen began the work, but the men he made were idiots with great bellies, for he could not inspire them with knowledge; so that in every thing but in shape, they resembled the beasts of the field. They had no passion but to satisfy their carnal appetites.

“Brimha, offended at the men, destroyed them, and produced four persons from his own breath, whom he called by four different names. The name of the first was Sinnoc, [Body.] of the second, Sinnunda, [Life.] of the third, Sonnatin, [Permanency.] and of the fourth, Sonninkunar. [Intellectual existence.] These four persons were ordered by Brimha, to rule over the creatures, and to possess for ever the world. But they refused to do any thing but to praise God, having nothing of the destructive quality [Timmugoon.] in in their composition.

“Brimha, for this contempt of his orders, became angry, and lo! a brown spirit started from between his eyes. He sat down before Brimha, and began to weep: then lifting up his eyes, he asked him, “Who am I, and where shall be the place of my abode? Thy name shall be Rudder, [The weeper; because he was produced in tears. One of the names of Shibah, the destructive attribute of the divinity.] said Brimha, and all nature shall be the place of thine abode. But rise up, O Rudder! and form man to govern the world.

“Rudder immediately obeyed the orders of Brimha. He began the work, but the men he made were fiercer than tigers, having nothing but the destructive quality in their compositions. They, however, soon destroyed one another, for anger was their only passion. Brimha, Bishen, and Rudder, then joined their different powers. They created ten men, whose names were, Narud, Dico, Bashista, Birga, Kirku, Pulla, Pulista, Ongira, Otteri and Murichi: [The significations of these ten names are, in order, these: Reason, Ingenuity, Emulation, Humility, Piety, Pride, Patience, Charity, Deceit, Mortality.] The general appellation of the whole, was the Munies. [The Inspired.] Brimha then produced Dirmo [ Fortune.] from his breast, Adirmo [Misfortune.] from his back, Loab [Appetite.] from his lip, and Kam [Love.] from his heart. This last being a beautiful female, Brimha looked upon her with amorous eyes. But the Munies told him, that she was his own daughter; upon which he shrunk back, and produced a blushing virgin called Ludja. [Shame.] Brimha thinking his body defiled by throwing his eyes upon Kâm, changed it, and produced ten women, one of which was given to each of the Munies.”

In this division of the Bedang Shaster, there is a long list of the Surage Buns, or children of the sun, who, it is said, ruled the world in the first periods. But as the whole is a mere dream of imagination, and scarcely the belief of the Hindoo children and women, we shall not trespass further on the patience of the public with these allegories. The Brahmins of former ages wrote many volumes of romances upon the lives and actions of those pretended kings, inculcating, after their manner, morality by fable. This was the grand fountain from which the religion of the vulgar in India was corrupted; if the vulgar of any country require any adventitious aid to corrupt their ideas upon so mysterious a subject.

Upon the whole, the opinions of the author of the Bedang, upon the subject of religion, are not unphilosophical. He maintains that the world was created out of nothing by God, and that it will be again annihilated. The unity, infinity, and omnipotence of the supreme divinity, are inculcated by him: for though he presents us with a long list of inferior beings, it is plain that they are merely allegorical; and neither he nor the sensible part of his followers believe their actual existence. The more ignorant Hindoos, it cannot be denied, think that these subaltern divinities do exist, in the same manner, that Christians believe in angels: but the unity of God was always a fundamental tenet of the uncorrupted faith of the more learned Brahmins.

The opinion of this philosopher, that the soul, after death, assumes a body of the purer elements, is not peculiar to the Brahmins. It descended from the Druids of Europe, to the Greeks, and was the same with the [x] of Homer. His idea of the manner of the transmigration of the human soul into various bodies, is peculiar to himself. As he holds it as a maxim that a portion of the GREAT SOUL, or God, animates every living thing; he thinks it no ways inconsistent, that the same portion that gave life to man, should afterwards pass into the body of any other animal. This transmigration does not, in his opinion, debase the quality of the soul: for when it extricates itself from the fetters of the flesh, it reassumes its original nature.

The followers of the BEDANG SHASTER do not allow that any physical evil exists. They maintain that God created all things perfectly good, but that man, being a free agent, may be guilty of moral evil: which, however, only respects himself and society, but is of no detriment to the general system of nature. God, say they, has no passion but benevolence; and being possessed of no wrath, he never punishes the wicked, but by the pain and affliction which are the natural consequences of evil actions. The more learned Brahmins therefore affirm, that the hell which is mentioned in the Bedang, was only intended as a mere bugbear to the vulgar, to enforce upon their minds the duties of morality: for that hell is no other than a consciousness of evil, and those bad consequences which invariably follow wicked deeds.

Before we shall proceed to the doctrine of the NEADIRSEN SHASTER, it may not be improper to give a translation of the first chapter of the Dirm SHASTER, which throws a clear light upon the religious tenets common to both the grand sects of the Hindoos. It is a dialogue between Brimha, or the wisdom of God; and Narud, or human reason.

NARUD.

[Brimha, as we have already observed, is the genitive of Brimh; as Wisdom is, by the Brahmins, reckoned the chief attribute of God.] O thou first of God! Who is the greatest of all Beings?

BRIMHA.

BRIMH; who is infinite and almighty.

NARUD.

Is he exempted from death?

BRIMHA.

He is: being eternal and incorporeal.

NARUD.

Who created the world?

BRIMHA.

God, by his power.

NARUD.

Who is the giver of bliss?

BRIMHA.

KRISHEN: and whosoever worshippeth him, shall enjoy heaven. [Krishen is derived from Krish giving, and Ana joy. It is one of the thousand names of God.]

NARUD.

What is his likeness?

BRIMHA.

He hath no likeness: but to stamp some idea of him upon the minds of men, who cannot believe in an immaterial being, he is represented under various symbolical forms.

NARUD.

What image shall we conceive of him?

BRIMHA.

If your imagination cannot rise to devotion without an image; suppose with yourself, that his eyes are like the Lotos, his complexion like a cloud, his clothing of the lightning of heaven, and that he hath four hands.

NARUD.

Why should we think of the almighty in this form?

BRIMHA.

His eyes may be compared to the Lotos, to shew that they are always open, like that flower which the greatest depth of water cannot surmount. His complexion being like that of a cloud, is an emblem of that darkness with which he veils himself from mortal eyes. His clothing is of lightning, to express that awful majesty which surrounds him: and his four hands are symbols of his strength and almighty power.

NARUD.

What things are proper to be offered unto him?

BRIMHA.

Those things which are clean, and offered with a grateful heart. But all things which by the law are reckoned impure, or have been defiled by the touch of a woman in her times; things which have been coveted by your own soul, seized by oppression, or obtained by deceit, or that have any natural blemish, are offerings unworthy of God.

NARUD.

We are commanded then to make offerings to God of such things as are pure and without blemish, by which it would appear that God eateth and drinketh, like mortal man, or if he doth not, for what purpose are our offerings?

BRIMHA.

God neither eats nor drinks like mortal men. But if you love not God, your offerings will be unworthy of him; for as all men covet the good things of this world, God requires a free offering of their substance, as the strongest testimony of their gratitude and inclinations towards him.

NARUD.

How is God to be worshipped?

BRIMHA.

With no selfish view; but for love of his beauties, gratitude for his favours, and for admiration of his greatness.

NARUD.

How can the human mind fix itself upon God, being that it is in its nature changeable, and perpetually running from one object to another?

BRIMHA.

True: the mind is stronger than an elephant, whom men have found means to subdue, though they have never been able entirely to subdue their own inclinations. But the ankush [Ankush is an iron instrument used for driving elephants.] of the mind is true wisdom, which sees into the vanity of all worldly things.

NARUD.

Where shall we find true wisdom?

BRIMHA.

In the society of good and wise men.

NARUD.

But the mind, in spite of restraint, covets riches, women, and all worldly pleasures. How are these appetites to be subdued?

BRIMHA.

If they cannot be overcome by reason, let them be mortified by penance. For this purpose it will be necessary to make a public and solemn vow, lest your resolution should be shaken by the pain which attends it.

NARUD.

We see that all men are mortal, what state is there after death?

BRIMHA.

The souls of such good men as retain a small degree of worldly inclinations, will enjoy Surg [Heaven.] for a time; but the souls of those who are holy, shall be absorbed into God, never more to reanimate flesh. The wicked shall be punished in Nirick [Hell.] for a certain space, and afterwards their souls are permitted to wander in search of new habitations of flesh.

NARUD.

Thou, O Father, dost mention God as one; yet we are told, that Râm, whom we are taught to call God, was born in the house of Jessarit: that Kishen, whom we call God, was born in the house of Basdeo, and many others in the same manner. In what light are we to take this mystery?

BRIMHA.

You are to look upon these as particular manifestations of the providence of God, for certain great ends; as in the case of the sixteen hundred women, called Gopi, when all the men of Sirendiep [The island of Ceylon.] were destroyed in war. The women prayed for husbands, and they had all their desires gratified in one night, and became with child. But you are not to suppose that God, who is in this case introduced as the actor, is liable to human passions or frailties, being, in him. self, pure and incorporeal. At the same time he may appear in a thousand places, by a thousand names, and in a thousand forms; yet continue the same unchangeable, in his divine nature. --

Without making any reflections upon this chapter of the Dirm SHASTER, it appears evident, that the religion of the Hindoos has hitherto been very much misrepresented in Europe. The followers of the NEADIRSEN SHASTER, differ greatly in their philosophy from the sect of the BEDANG, though both agree about the unity of the supreme being. To give some idea of the Neadirsen philosophy, we shall, in this place, give some extracts from that Shaster.

NEADIRSEN is a compound from NEA, signifying right, and Dirsen, to teach or explain; so that the word may be translated an exhibition of truth. Though it is not reckoned so ancient as the Bedang, yet it is said to have been written by a philosopher called Goutam, near four thousand years ago. The philosophy contained in this Shaster, is very abstruse and metaphysical; and therefore it is but justice to Goutam to confess, that the author of the Dissertation, nota withstanding the great pains he took to have proper definitions of the terms, is by no means certain, whether he has fully attained his end. In this state of uncertainty he chose to adhere to the literal meaning of words, rather than, by a free translation, to deviate perhaps from the sense of his author.

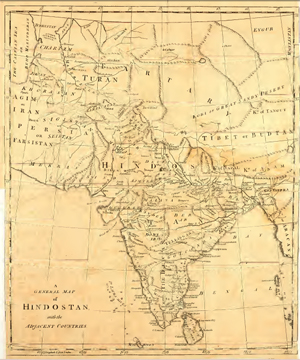

The generality of the Hindoos of Bengal, and all the northern provinces of Hindostan, esteem the NEADIRSEN a sacred Shaster; but those of the Decan, Coromandel, and Malabar, totally reject it. It consists of seven volumes. The first only came to the hands of the author of the Dissertation, and he has, since his arrival in England, deposited it in the British Museum. He can say nothing for certain concerning the contents of the subsequent volumes; only that they contain a complete system of the theology and philosophy of the Brahmins of the Neadirsen sect.

Goutam does not begin to reason a priori, like the writer of the Bedang. He considers the present state of nature, and the intellectual faculties, as far as they can be investigated by human reason; and from thence he draws all his conclusions. He reduces all things under six principal heads; substance, quality, motion, species, assimulation, and construction. [These are in the original Shanscrita, Dirba, Goon, Kirmo, Summania, Bishesh, Sammabae.] In substance, besides time, space, life, and spirit, he comprehends earth, water, fire, air, and akash. The four grosser elements, he says, come under the immediate comprehension of our bodily senses; and akash, time, space, soul, and spirit, come under mental perception.

He maintains, that all objects of perception are equally real, as we cannot comprehend the nature of a solid cubit, any more than the same extent of space. He affirms, that distance in point of time and space are equally incomprehensible; so that if we shall admit that space is a real existence, time must be so too: that the soul, or vital principle, is a subtile element, which pervades all things; for that intellect, which, according to experience in animals, cannot proceed from organization and vital motion only, must be a principle totally distinct from them.

“The author of the Bedang,” [A system of sceptical philosophy, to which many of the Brahmins adhere.] says Goutam, "finding the impossibility of forming an idea of substance, asserts that all nature is a mere delusion. But as imagination must be acted upon by some real existence, as we cannot conceive that it can act upon itself, we must conclude that there is something real, otherwise philosophy is at an end."

He then proceeds to explain what he means by his second principle, or Goon, which, says he, comprehends twenty-four things; form, taste, smell, touch, sound, number, quantity, gravity, solidity, fluidity, elasticity, conjunction, separation, priority, posteriority, divisibility, indivisibility, accident, perception, ease, pain, desire, aversion, and power [The twenty-four things are, in the Shanscrita, in order, these: Rup, Ris, Gund, Supursa, Shubardo, Sirica, Purriman, Gurritte, Dirbitte, Sinniha, Shanskan, Sangoog, Bibag, Pirrible, Particca, Apporticta, Addaristo, Bud, Suc, Duc, Itcha, Desh, Jotna.]. Kirmo or motion is, according to him, of two kinds, direct and crooked. Sammania, or species, which is his third principle, includes all animals and natural productions. Bishesh he defines to be a tendency in matter towards productions; and Sammabae, or the last principle, is the artificial construction or formation of things, as a statue from a block of marble, a house from stones, or cloth from cotton.

Under these six heads, as we have already observed, Goutam comprehends all things which fall under our comprehension; and after having reasoned about their nature and origin in a very philosophical manner, he concludes with asserting, that five things must of necessity be eternal. The first of these is Pirrum Attima, or the GREAT SOUL, who, says he, is immaterial, one, invisible, eternal, and indivisible, possessing omniscience, rest, will, and power [These properties of the divinity are the following in order: Nidakaar, Akitta, Odėrisa, Nitte, Apparticta, Budsirba, Sụck, Itcha, Jotna.].

The second eternal principle is the Jive Attima, or the vital soul, which he supposes is material, by giving it the following properties; number, quantity, motion, contraction, extension, divisibility, perception, pleasure, pain, desire, aversion, accident, and power. His reasons for maintaining that the vital soul is different from the great soul, are very numerous, and it is upon this head that the followers of the Bedang and Neadirsen are principally divided. The first affirm that there is no soul in the universe but God, and the second strenuously hold that there is, as they cannot conceive that God can be subject to such affections and passions as they feel in their own minds; or that he can possibly have a propensity to evil. Evil, according to the author of the Neadirsen Shaster, proceeds entirely from Jive Attima, or the vital soul. It is a selfish craving principle, never to be satisfied; whereas God remains in eternal rest, without any desire but benevolence.

Goutam's third eternal principle is time or duration, which, says he, must of necessity have existed while any thing did exist; and is therefore infinite. The fourth principle is space or extension, without which nothing could have been; and as it comprehends all quantity, or rather is infinite, he maintains that it is indivisible and eternal. The fifth eternal principle is Akash, a subtile and pure element, which fills up the vacuum of space, and is compounded of purmans or quantities, infinitely small, indivisible, and perpetual. “God,” says he, “can neither make nor annihilate these atoms, on account of the love which he bears to them, and the necessity of their existence; but they are, in other respects, totally subservient to his pleasure.”

“God," says Goutam, “at a certain season, endued these atoms, as we may call them, with Bishesh or plasticity, by virtue of which they arranged themselves into four gross elements, fire, air, water, and earth. These atoms being, from the beginning, formed by God into the seeds of all productions, Jive Attima, or the vital soul, associated with them, so that animals and plants, of various kinds, were produced upon the face of the earth.”

"The same vital soul," continues Goutam, " which before associated with the Purman of an animal, may afterwards associate with the Purman of a man.” This transmigration is distinguished by three names, Mirt, Mirren, and Pirra-purra-purvesh, which last literally signifies the change of abode. The superiority of man, according to the philosophy of the Neadirsen, consists only in the finer organization of his parts, from which proceed reason, reflection, and memory, which the brutes only possess in an inferior degree, on account of their less refined organs.

Goutam supposes, with the author of the Bedang, that the soul after death, assumes a body of fire, air, and akash, unless in the carnal body it has been so purified by piety and virtue, that it retains no selfish inclinations. In that case it is absorbed into the GREAT SOUL OF NATURE, never more to reanimate flesh. Such, says the philosopher, shall be the reward of all those who worship God from pure love and admiration, without any selfish views. Those that shall worship God from motives of future happiness, shall be indulged with their desires in heaven for a certain time. But they must also expiate their crimes, by, suffering adequate punishments; and afterwards their souls will return to the earth, and wander about for new habitations. Upon their return to the earth they shall casually associate with the first organized Purman they shall meet. They shall not retain any consciousness of their former state, unless it is revealed to them by God. But those favoured persons are very few, and are distinguished by the name of Jates Summon [The acquainted with their former state.].

The author of the Neadirsen teaches, for the purposes of morality, that the sins of the parents will descend to their posterity; and that, on the other hand, the virtues of the children will mitigate the punishments of the parents in Nirick, and hasten their return to the earth. Of all sins he holds ingratitude [Mitterdro.] to be the greatest. “Souls guilty of that black crime,” says he, “will remain in hell while the sun remains in heaven, or to the general dissolution of all things.”

"Intellect,” says Goutam, “is formed by the combined action of the senses.” He reckons six senses: five external [Chakous, Shraban, Rasan, Granap, Tawass.], and one internal. The last he calls Manus, by which he seems to mean conscience. In the latter he comprehends reason, perception [Onnuman, reason. Upimen, perception.], and memory: and be concludes, that by their means only mankind may possibly acquire knowledge. He then proceeds to explain the manner by which these senses act.

“Sight,” says he, “arises from the Shanskar, or repulsive qualities of bodies, by which the particles of light which fall upon them are reflected back upon the eyes from all parts of their surfaces. Thus the object is painted in a perfect manner upon the organ of seeing, whither the soul repairs to receive the image.” He affirms, that unless the soul fixes its attention upon the figure in the eye, nothing can be perceived by the mind; for a man in a profound reverie, though his eyes are open to the light, perceives nothing. Colours, says Goutam, are particular feelings in the eye, which are proportioned to the quantity of light reflected from any solid body.

Goutam defines hearing in the same manner with the European philosophers, with this difference only, that he supposes, that the sound which affects the ear is conveyed through the purer element of akash, and not by the air; an error which is not very surprising in a speculative philosopher. Taste he defines to be a sensation of the tongue and palate, occasioned by the particular form of those particles which compose food. Smell, says he, proceeds from the effluvia which arise from bodies to the nostrils. The feeling which arises from touching, is occasioned by the contact of dense bodies with the skin, which, as well as the whole body, excepting the bones, the hair, and the nails, is the organ of that sense. There runs, says he, from all parts of the skin, very small nerves to a great nerve, which he distinguishes by the name of Medda. This nerve is composed of two different coats, the one sensitive and the other insensitive. It extends from the crown of the head down the right side of the vertebræ to the right foot [To save the credit of Goutam, in this place, it is necessary to observe, that anatomy is not at all known among the Hindoos, being strictly prohibited from touching a dead body by the severest ties of religion.]. When the body becomes languid, the soul, fatigued with action, retires within the insensible coat, which checks the operation of the senses, and occasions sound sleep. But should there remain in the soul a small inclination to action, it starts into the sensitive part of the nerve, and dreams immediately arise before it. These dreams, says he, invariably relate to something perceived before by the senses, though the mind may combine the ideas together at pleasure.

Manus, or conscience, is the internal feeling of the mind, when it is no way affected by external objects. Onnuman, or reason, says Goutam, is that faculty of the soul which enables us to conclude that things and circumstances exist, from an analogy to things which had before fallen under the conception of our bodily senses: for instance, when we see smoke, we conclude that it proceeds from a fire; when we see one end of a rope, we are persuaded that it must have another.

By reason, continues Goutam, men perceive the existence of God; which the Boad or Atheists deny, because his existence does not come within the comprehension of the senses. These atheists, says he, maintain that there is no God but the universe; that there is neither good nor evil in the world; that there is no such thing as a soul; that all animals exist by a mere mechanism of the organs, or by a fermentation of the elements; and that all natural productions are but the fortuitous concourse of things.

The philosopher refutes these atheistical opinions by a long train of arguments, such as have been often urged by European divines. Though superstition and custom may bias reason to different ends, in various countries, we find a surprising similarity in the arguments used by all nations against the BOAD, those common enemies of every system of religion.

“Another sect of the BOAD,” says Goutam, “are of opinion that all things were produced by chance [Addaristo.]." This doctrine he thus refutes. "Chance is so far from being the origin of all things, that it has but a momentary existence of its own; being alternately created and annihilated at periods infinitely small, as it depends entirely on the action of real essences. This action is not accidental, for it must inevitably proceed from some natural cause. Let the dice be rattled eternally in the box, they are determined in their motion, by certain invariable laws. What therefore we call chance is but an effect proceeding from causes which we do not perceive."

“Perception,” continues Goutam, "is that faculty by which we instantaneously know things without the help of reason. This is perceived by means of relation, or some distinguishing property in things, such as high and low, long and short, great and small, hard and soft, cold and hot, black and white.”

Memory, according to Goutam, is the elasticity of the mind, and is employed in three different ways: on things present as to time, but absent as to place; on things past, and on things to come. It would appear from the latter part of the distinction, that the philosopher comprehends imagination in memory. He then proceeds to define all the original properties of matter, and all the passions and faculties of the mind. He then descants on the nature of generation.

"Generation,” says he, “may be divided into two kinds; Jonidge, or generation by copulation; and adjonidge, generation without copulation. All animals are produced by the first, and all plants by the latter. The purman, or seed of things, was formed from the beginning with all its parts. When it happens to be deposited in a matrix suitable to its nature, a soul associates with it; and, by assimulating more matter, it gradually becomes a creature or plant; for plants, as well as animals, are possessed of a portion of the vital soul of the world.”

Goutam, in another place, treats diffusely of providence and free will. He divides the action of man under three heads: the will of God, the power of man, and casual or accidental events. In explaining the first, he maintains a particular providence; in the second, the freedom of will in man; and in the third, the common course of things, according to the general laws of nature. With respect to providence, though he cannot deny the possibility of its existence, without divesting God of his omnipotence, he supposes that the deity never exerts that power, but that he remains in eternal rest, taking no concern, neither in human affairs nor in the course of the operations of nature.

The author of the Neadirsen maintains that the world is subject to successive dissolutions and renovations at certain stated periods. He divides these dissolutions into the lesser and the greater. The lesser dissolution will happen at the end of a revolution of the Jugs. The world will be then consumed by fire, and the elements shall be jumbled together, and after a certain space of time they will again resume their former order. When a thousand of those smaller dissolutions shall have happened, a MAHPERLEY or great dissolution will take place. All the elements will then be reduced to their original purmans or atoms, in which state they shall long remain. God will then, from his mere goodness and pleasure, restore Bishesh or plasticity. A new creation will arise; and thus things have revolved in succession, from the beginning, and will continue to do so to eternity.

These repeated dissolutions and renovations have furnished an ample field for the inventions of the Brahmins. Many allegorical systems of creation are upon that account contained in the Shasters. It was for this reason that so many different accounts of the cosmogony of the Hindoos have been promulgated in Europe; some travellers adopting one system, and some another. Without deviating from the good manners due to those writers, we may venture to affirm that their tales upon this subject are extremely puerile, if not absurd. They took their accounts from any common Brahmin, with whom they chanced to meet, and never had the curiosity or industry to go to the fountain head.

In some of the renovations of the world, Brimha, or the wisdom of God, is represented in the form of an infant with his toe in his mouth, floating on a comala or water flower, or sometimes upon a leaf of that plant, upon the watery abyss. The Brahmins mean no more by this allegory, than that at that time the wisdom and designs of God will appear, as in their infant state. Brimha floating upon a leaf shows the instability of things at that period. The toe which he sucks in his mouth implies, that infinite wisdom subsists of itself; and the position of Brimha's body is an emblem of the endless circle of eternity.

We see Brimha sometimes creeping forth from a winding shell. This is an emblem of the untraceable way by which divine wisdom issues forth from the infinite ocean of God. He, at other times, blows up the world with a pipe, which implies, that the earth is but a bubble of vanity, which the breath of his mouth can destroy. Brimha, in one of the renovations, is represented in the form of a snake, one end of which is upon a tortoise which floats upon the vast abyss, and upon the other, he supports the world. The snake is the emblem of wisdom; the tortoise is a symbol of security, which figuratively signifies providence; and the vast abyss is the eternity and infinitude of God.

What has been already said has, it is hoped, thrown a new light on the opinions of the Hindoos upon the subject of religion and philosophical inquiry. We find that the Brahmins, contrary to the ideas formed of them in the West, in- variably believe in the unity, eternity, omniscience, and omnipotence of God: that the polytheism of which they have been accused, is no more than a symbolical worship of the divine attributes, which they divide into three principal classes. Under the name of Brimha, they worship the wisdom and creative power of God; under the appellation of Bishen, his providential and preserving quality; and under that of SHIBAH, that attribute which tends to reduce matter to its original principles.

This system of worship, say the Brahmins, arises from two opinions. The first is, that as God is immaterial, and consequently invisible, it is impossible to raise a proper idea of him by any image in the human mind. The second is, that it is necessary to strike the gross ideas of man with some emblems of God's attributes, otherwise, that all sense of religion will naturally vanish from the mind. They, for this purpose, have made symbolical representations of the three classes of the divine attributes; but they aver, that they do not believe them to be separate intelligences. BRIMH, or the supreme divinity, has a thousand names; but the Hindoos would think it the grossest impiety to represent him under any form. “The human mind,” say they, “may form some conception of his attributes separately, but who can grasp the whole within the circle of finite ideas?”

That in any age or country, human reason was ever so depraved as to worship the work of hands for the Creator of the universe, we believe to be an absolute deception, which arose from the vanity of the abettors of particular systems of religion. To attentive inquirers into the human mind, it will appear, that common sense, upon the affairs of religion, is pretty equally divided among all nations. Revelation and philosophy have, it is confessed, lopped off some of those superstitious excrescences and absurdities that naturally arise in weak minds upon a subject so mysterious: but it is much to be doubted, whether the want of those necessary purifiers of religion ever involved any nation in gross idolatry, as many ignorant zealots have pretended.

In India, as well as in many other countries, there are two religious sects: the one look up to the divinity through the medium of reason and philosophy; while the others receive, as an article of their belief, every holy legend and allegory which have been transmitted down from antiquity. From a fundamental article in the Hindoo faith, that God is the soul of the world, and is consequently diffused through all nature, the vulgar revere all the elements, and consequently every great natural object, as containing a portion of God; nor is the infinity of the supreme being, easily comprehended by weak minds, without falling into this error. This veneration for different objects, has, no doubt, given rise among the common Indians, to an idea of subaltern intelligences; but the learned Brahmins, with one voice, deny the existence of inferior divinities: and, indeed, all their religious books of any antiquity confirm that assertion.

[End of the Dissertation.]