Chapter 7: Anquetil-Duperron's Search for the True Vedas

In 1762, after his return from India, Abraham Hyacinthe ANQUETIL-DUPERRON (1731-1805) wrote to one of his former classmates at a Jansenist seminary in Utrecht, Holland:

To deepen the understanding of the history of ancient peoples, to elaborate the revolutions which peoples and languages undergo, to visit regions unknown to the rest of the people where art has preserved the character of the first ages: you will perhaps remember, with distress and sighing about my follies, that these subjects have always been the focus of my attention. (Schwab 1934:18)

From his youth, Anquetil-Duperron's interest in the world's first ages was connected to a deep religiosity that put him on the path to priesthood. It is probably during his theological studies at the Sorbonne that young Anquetil-Duperron wrote a manuscript of about a hundred pages that is now part of his dossier at the Bibliotheque Nationale in Paris.1 It is titled "Le Parfait theologien" (The Perfect Theologian), but the word "Parfait" is doubly struck through. The title is emblematic for Anquetil-Duperron's career; and the manuscript, ignored even by Anquetil-Duperron's biographers,2 merits a look.

The Perfect [crossed-out] Theologian

Anquetil-Duperron starts out by insisting that theology is "a science like philosophy" but must, unlike philosophy, stay within the limits circumscribed by "a genuine revelation, the mysteries of religion, and several dogmas transmitted to us by apostolic tradition," which form the bedrock that no one is allowed to question (p. 369r). Since natural religion is also a subject of philosophy, the proper realm of theology is that of revelation (p. 371r). Yet the idea that people have of theology is far too narrow, and Anquetil-Duperron wants in this manuscript to show how broad and deep theology must be. Chapter 3 is titled "That a theologian must be almost universal" and argues that, faced with many pretended revelations, a theologian must be equipped to judge their claims. This indicates the need for knowledge of several languages in order to read the original texts; of history to understand their context; of geography to understand their setting; and of poetry to appreciate their style. "All such knowledge thus forms part of theology" (p. 373v). Furthermore, a real theologian should know not only the Old and New Testaments and all related languages but everything ever divinely revealed and transmitted (p. 375r). He must also question Old Testament authorship:

Is Moses really the first of all writers, as has been asserted by some fathers? If that was the case, where did he get his creation story and deluge story and even the Abraham story from? Did he prophesy the past, as a monk has recently argued? Or has he only reported things that were known in his time and that he could have learned from the tradition of the patriarchs because of the long lifespan of the first humans, as the majority of authors think? But who can say if there were not other historians before Moses, and earlier books? (p. 381V)

A theologian worth the name has to go to the bottom of all these questions, research all opinions and sources ancient and modern, and must especially "discover the systems of Chaldaea, Phoenicia, and Egypt" (p. 393r). Another "thorny question" that "requires infinite caution" is that of Paradise and Adam's sin:

What is this delicious garden of which we are told? Where was it? What has become of it? 1. Was it on the moon or in the air, as some fathers have believed? 2. Was it exclusively spiritual or corporeal, or both together as St. John Damascene thought? 3. Was it in the Orient? In Syria? In Armenia? Or close to India [vers le mogol], where one ordinarily places it? 4. Or was it the entire habitable earth, as some theologians have asserted? 5. How can one reconcile what Genesis says about these four rivers [of paradise] with geography as it is now known? 6. Could the location have changed? What proofs are there of that? 7. If there is no proof: must one take recourse to parables? (p. 393v)

Such is the kind of questions over which young Anquetil-Duperron pondered. He asked himself why Moses put this narration of Adam's sin in the book of Genesis, why the angels rebelled, whether the deluge was universal, and other pressing questions (pp. 394r-v). A perfect theologian must go beyond the biblical text and learn about the histories of other peoples, including the Greeks and the Chinese, and about their religions and arts (p. 407r). With regard to languages, a theologian ought to master not only standard Hebrew and rabbinical Hebrew but also Greek, Syriac, Arabic, and Ethiopian (pp. 414v-41v), and he should also study the histories and philosophies of these peoples. After dozens of pages filled with such desiderata, Anquetil-Duperron begins to deal with the critical analysis of concrete texts, but this is where the manuscript abruptly ends (p. 481r).

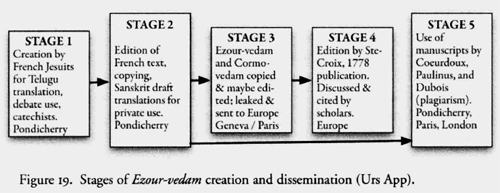

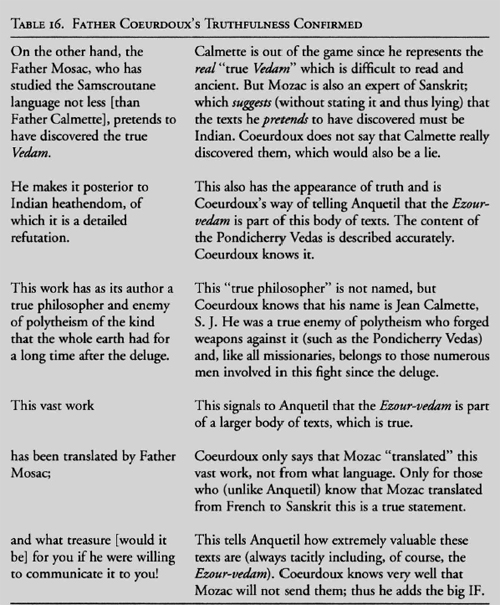

Anquetil-Duperron's early manuscript already shows his interest in ancient textual sources and his boundless thirst for knowledge, and it defines the field of revelation as his working area. The task the young man had set for himself seems daunting, but his search for genuine ancient records of God's earliest revelations was to carry him far beyond the Middle East and become a drawn-out quest for the Indian Vedas that lasted from his youth to his death in 1805. His last publication -- a posthumously published annotated translation of Father Paulinus a Sancto Bartholomaeo's Viaggio alle Indie orientali (Voyage to the East Indies, 1796) that appeared in 1808 -- shows the end point of Anquetil-Duperron's theological journey of a lifetime. Taking issue with Paulinus's statement that the Ezour-vedam was "composed by a missionary and falsely attributed to the brahmins" and that the Indians' conception of Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva clearly shows "the materialism of the Indians" and their pagan philosophy (Paulinus a Sancto Bartholomaeo 1796:66), Anquetil-Duperron vigorously defended the Ezour-vedam's genuineness ("a donkey can deny more than a philosopher can prove"3) as well as the orthodoxy of the Indian trinity:

The missionary [Paulinus] keeps forgetting that by his comparisons with the false Orpheus, the fake oracles of Zoroaster, Hermes, and the Egyptians he gives an air of falsity to the Indian dogmas .... It is no surprise that one finds the trinity in Plato, with the Egyptians, and possibly with the Pythagoreans: the earliest sages, the philosophers, have always been careful to preserve and meditate on the ancient truths. In the one finds the supreme Being, his word, his spirit. (Paulinus a Sancto Bartholomaeo 1808:3.419)

Anquetil-Duperron wrote that until Paulinus "makes positively known" who the author of the Ezour-vedam was "one cannot trust his magisterial assertions regarding erudition about India" (p. 120). But by the time this challenge was published, both Anquetil-Duperron (d. 1805) and Paulinus (d. 1806) were dead. In the meantime, several authors have faced that challenge, but so far the debate has ended inconclusively. The last word came from Ludo Rocher who, in his 1984 monograph on the Ezour-vedam, offers much interesting information but ends the discussion of authorship not with a culprit but with a list of suspects:

The question who the French Jesuit author of the EzV [Ezour-vedam] was we can only speculate on. Calmette was very much involved in the search for the Vedas; Mosac is a definite possibility; there may by some truth to Maudave's information on Martin; there is no way of verifying the references to de Villette and Bouchet. The author of the EzV may be one of these, but he may also be one of their many more or less well-known confreres. In the present state of our knowledge, we cannot go any further than that. (Rocher 1984:60)

What I said above already made me suspect that not only the Ezour-Vedam was a French work, but that the P. Calmette was the author. To acquire the certainty I had thought to speak to that, all of Paris, was the better to know the status of the issue. The venerable Abbé Dubois, who was a missionary for forty years in India, who lived with the last Jesuit missionaries, and who lived in Pondicherry, has no doubt seen, I said to myself, those curious manuscripts which made so much noise. I went on to find, and without letting him know my opinion, I asked him if we knew the author of the Ezour-Veda. "This is the P. Calmette," he told me at once. But, he added, several missionaries got their hands on it. I needed no more. I had rediscovered the trace of the illustrious Indianist who was the initiator of French scholars in this branch which is so flourishing today.

-- The Father Calmette and the Indianist Missionaries, by Father Julien Bach

In this chapter I will take up Anquetil-Duperron's challenge and offer my answer on the backdrop of a broader sequence of events: the European discovery of India's oldest sacred literature. How did Anquetil-Duperron come to regard the Ezour-vedam as genuine; and why could he, an ardent Christian, call Vedic texts "orthodox"?

Approaching the Vedas

Theological questions very much like those posed by young Anguetil-Duperron were the major motivation for the study of ancient languages and histories, and as textual critique and conflicts between secular (Chinese, Egyptian, etc.) and sacred (biblical) history stirred up debates in Europe, the study of ancient oriental languages and texts became increasingly important. Books possibly older than the Pentateuch were of special interest.

As we have seen, rumors circulated about the book of Enoch, which for a long time was regarded as possibly the oldest book in the world. It was coveted by eminent European intellectuals such as Reuchlin, Peiresc, and Kircher (Schmidt 1922) and stimulated the study of Ethiopian. Then the Jesuit figurists in China identified Enoch with Fuxi and the Yijing seemed for a while to be the world's oldest book. Its study stimulated the study of ancient Chinese texts and produced a number of excellent Sinologists like Premare, Visdelou, Foucquet, and Gaubil.

India was also associated with Enoch's book since 1553 when Guillaume Postel suggested in De originibus that "treasures of antediluvian books" stored in India could include "the work of Enoch" (Postel 1553b:72). But scriptures of Indian rather than mideastern origin were also mentioned among the world's oldest. Henry Lord's 1630 book stated in the introduction that God gave Brammon "a Booke, containing the forme of divine Worshippe and Religion" (p. 5). Since this divine work (which Brammon took to the East, "the most noble part of the world") reportedly was transmitted in the first world age, it must have been the world's oldest book; but it was lost at the end of the first yuga. In the second world age, after the great flood, God again "communicated Religion to the world" in "a book of theirs called the SHASTER, which is to them as their Bible, containing the grounds of their Religion in a written word" and was delivered "out of the cloud into the hand of Bremaw" (Lord 1630: Introduction). Lord's Shaster is said to consist of three tracts -- a book of precepts, the ceremonial law, and the observations of castes (p. 40) -- of which Lord translated some parts garnished with his (mostly critical) comments. But this information got relatively little publicity in Europe.4 The same author's "The Religion of the Persees" described the religion of the Parsees in India, who have a "Booke, delivered to Zertoost [Zarathustra], and by him published to the Persians or Persees" (p. 27) and furnished translations of some extracts. Lord's two thin volumes, which are often bound together, deal exactly with the two major areas of Anquetil-Duperron's work more than a century later: his research on the oldest texts of Persian origin found in India's Parsee community at Surat and his work on ancient India's religious literature.

For people in search of the world's oldest books, India's mysterious Vedas had a particular attraction, even though -- or perhaps because -- information about them often consisted of little more than the names of its four parts and the assertion of great antiquity. Agostinho de Azevedo's report about the Vedas and Shastras of India found its way into Johannes Lucena's Historia da Vida do Padre Francisco de Xavier (1600) and Diogo do Couto's Decada Quinta da Asia (1612), and from there into other works including Holwell's (see Chapter 6). The report in the Livro da Seita dos Indios Orientals by the Jesuit Giacomo Fenicio from the early seventeenth century was plagiarized by Baldaeus (1672) and also got some publicity. However, both Fenicio's and Azevedo's data were based not on the Vedas but on other texts.5

In the seventeenth century, bits and pieces of information about the Vedas from Heinrich Roth/Kircher, Francois Bernier, Jean Baptiste Tavernier, and others were floating around, and even Johann Joachim MULLER'S (1661-1733) (in)famous De tribus impostoribus contained a passage about them. The false date of 1598 on the original printed edition of these Three Impostors led some researchers6 to conclude that this book contained the earliest Western mention of the four Vedas; but Winfried Schroder has proved that the book is by Muller and was written almost a century later, in 1688 (Muller 1999; Mulsow 2002:119). Muller had been involved in oriental studies, and his Veda passage shows beautifully how competition by alternative revelations and older texts could be used to destabilize Christianity, whether in jest -- as seems to have been his intention -- or in earnest, as his readers understood it. Muller's passage about the Vedas occurs in the context of an attack on Christianity on the basis of competing revelations that form the basis of the sacred scriptures of the "three impostors" Moses, Jesus, and Mohammed:

By a special revelation? Who are you to say this? Good God! What a hotchpotch of revelations! Do you rely on the oracles of the heathen? Already antiquity laughed about this. How about the testimony of your priests? I offer you others who contradict them. Hold a debate: but who will be the judge? And what will be the outcome of the controversy? You cite the writings of Moses, of the prophets, and of the apostles? The Koran will be held against you which on the basis of the ultimate revelation calls them corrupt; and its author boasts of having cut by divine miraculous intervention the corruptions and quarrels of the Christians with his sword, like Moses those of the heathens. (Osterreichische Nationalbibliothek Wien, Cod. 19540, pp. 8-9)

After this argument of mutually contradictory absolute truth claims -- which was already advanced in the thirteenth century by Roger Bacon in the context of his discussion of the religious debates in front of the great Khan -- Muller brings up the delicate topic of chronology, which was much discussed after Martino Martini's publications of the 1650s:

Indeed, Mohammed subjugated Palestine by force, as had Moses, and both were guided by great miracles. And their followers oppose you, as do the Veda and the collections of the Brachmans that date from 14,000 years ago, to say nothing of the Chinese. You, who hide yourself in this corner of Europe dismiss these religions and deny their validity, and you are right to do so; but the others negate yours with the same ease. (p. 9)

This kind of "foreign" perspective was also adopted by the author of the Letters by a Turkish Spy which will be quoted below, and in the eighteenth century it was quite fashionable and used, for example, by Montesquieu in his Lettres Persanes and by Voltaire in many writings. Instead of making the "older-is-better" argument, however, Muller immediately undercuts the authority of even the oldest scriptures of the world:

And what miracle could not convince men if [they are so credulous as to believe] that the world has been born from a scorpion's egg, that the earth is carried on the head of a bull, and that the ultimate basis of things would be formed from the three Vedas if some jealous son of the Gods had not stolen the first three volumes? Our people would laugh about this, and this would be another argument for them in support of the soundness of their religion, even if it has no basis except in the brains of their priests. Besides, from where did they get those enormous amounts of scriptures, packed with lies, about the heathen gods? (p. 9)

At the end of the seventeenth century, the reputation of the Vedas and of Sanskrit for great antiquity was also reflected in the much-read Letters writ by a Turkish Spy, whose eight volumes were reprinted many times. The third volume contains the following observation that Holwell, among others, adduced in support of his idea of humanity's origin in India (Holwell 1771:3.157):

But that seems very strange which thou relatest, of a certain Language among the Indians, which is not vulgarly spoken; but that all their Books of Theology, and Pandects of their Laws, the Records of their Nation, and the Treatises of Human Arts and Sciences are written in it. And that this Language is taught in their Schools, Colleges, and Academies, even as Latin is among the Christians. I cannot enough admire at this; for, where and when was this Language spoken? How came it to be difus'd? There seems to be a Mystery in it, that none of their Brachmans can give any other Account of this, save, that it is the Language, wherein God gave, to the first Creature he made, the four Books of the Law: which according to their Chronology, was above Thirty Million Years ago. (Marana et al. 1723:3.171-72)

These "four Books of the Law" are of course the four Vedas. The continuation of this "Turkish Spy" letter beautifully shows the subversive potential of such news from the Orient at the end of the seventeenth century:

I tell thee, my dear Brother, this News has started some odd Notions in my Mind: For when I consider, That this Language, as thou sayest, Has nothing in it common with the Indian that is now spoken nor with any other Language of Asia, or the World; and yet, that it is a copious and regular Language, learne'd by Grammar, like the other material Languages; and that, in this obsolete Language Books are written, wherein it is asserted, That the World is so many Millions of Years old; I could almost turn Pythagorean, and believe, The World to be within a Minute of Eternal. And, where would be the Absurdity? Since God had equally the same infinite Power, Wisdom and Goodness, from all Eternity, as he had Five or Six thousand Years ago. What should hinder him then from exerting these divine Attributes sooner? What should retard him from drawing forth this glorious Fabrick earlier, from the Womb of Nothing? Suffer thy Imagination to start backwards, as far as thou canst, even to Millions of Ages, and yet thou canst not conceive a Time, wherein this fair unmeasurable Expanse was not stretch'd out. As if Nature her self had engraven on our Intellect, this Record of the Worlds untraceable Antiquity, in that our strongest, swiftest Thoughts, are far too weak and slow, to follow time back to its endless Origin." (p. 172)

De Nobili's Vedic Restoration Project

Since access to the Vedas was nearly impossible, most of the information about their content was pure fantasy. We have seen in the chapter on Holwell how easy it was to be misled by speculation. But a few missionaries (whose writings were mostly doomed to sleep in archives for several centuries) were in a position to consult vedic texts or question learned informants. The Jesuit Roberto DE NOBILI (1577-1656) obtained direct access to some Vedas from his teacher, a Telugu Brahmin called Shivadharma.

Nobili is the first European known to have read parts of the Vedas. In a number of his works defending his strategy of tolerating aspects of Brahminical lifestyle among his converts, he cites directly from the texts associated with the Black Yajur Veda... Nobili’s access to these texts was mediated by the Telugu Brahmin convert who taught him Sanskrit, Śivadharma or Bonifacio... Śivadharma, who had falling out with Nobili, assisted [Goncalo] Fernandes with scriptural quotations in his 1616 treatise attacking Nobili... as Fernandes did not know Sanskrit, the texts were translated into Tamil by Śivadharma and only thence into Portuguese by Fernandes with his assistant Andrea Buccerio. This kind of mediated access to Sanskrit texts, likely the same method used by Azevedo and Rogerius, would be repeated in the following century by other missionaries.

-- The Absent Vedas, by Will Sweetman

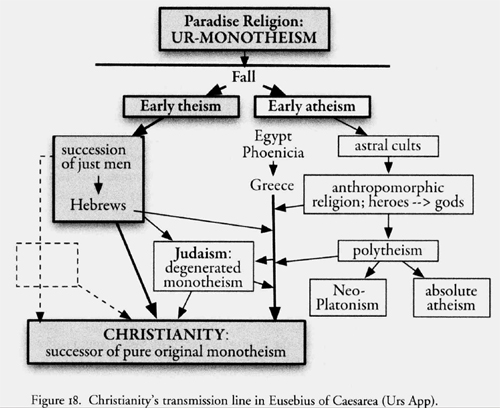

He wrote that the four traditional Vedas are "little more than disorderly congeries of various opinions bearing partly on divine, partly on human subjects, a jumble where religious and civil precepts are miscellaneously put together" (Rubies 2000:338). Having been told in 1608 that the fourth Veda was no longer extant, the missionary decided to proclaim himself "teacher of the fourth, lost Veda which deals with the question of salvation" (Zupanov 1999:116). De Nobili apparently believed, like his contemporary Matteo Ricci in China, that though original pure monotheism had degenerated into idolatry, vestiges of the original religion survived and could serve to regenerate the ancient creed under the sign of the Cross. After his failed experiment with Buddhist robes (see Chapter I), Ricci adopted the dress of a Confucian scholar, asserted that the Chinese had anciently been pure monotheists, and proclaimed Christianity to be the fulfillment of the doctrines found in ancient Chinese texts. A few years later, Ricci's compatriot de Nobili presented himself in India as an ascetic "sannayasi from the North" and "restorer of 'a lost spiritual Veda'" (Rubies 2000:339) who hailed from faraway Rome where the Ur-tradition had been best preserved. In his Relafao annual for the year 1608, Fernao Guerreiro wrote on a similar line that he was studying Brahmin letters to present his Christian message as a restoration of the spiritual Veda, the true original religion of all countries, including India whose adulterated vestiges were the religions of Vishnu, Brahma, and Shiva (p. 344).

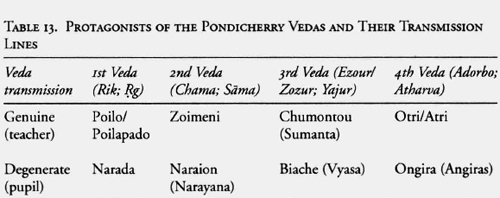

For de Nobili, the word "Veda" signified the spiritual law revealed by God. He called himself a teacher of Satyavedam, that is, the true revealed law, who had studied philosophy and this very law in Rome. He maintained that his was exactly the same law that "by God's order had been taught in earlier times by Sannyasins" in India (Bachmann 1972:154). De Nobili thus had come to India to restore satyavedam and to bring back, as the title of his didactic Sanskrit poem says, "The Essence of True Revelation [satyavedam]" (Castets 1935:40). De Nobili's description of the traditional Indian Vedas clearly shows that he did not regard them as "genuine Vedas" or genuine divine revelations. That de Nobili was for a long time suspected of being the author of the Ezour-vedam is understandable because in that text Chumontou has fundamentally the same role as de Nobili: he exposes the degenerate accretions of the reigning clergy's "Veda," represented by the traditional Veda compiler Biache (Vyasa), in order to teach them about satyavedam, the divine Ur-revelation whose correct transmission he represents against the degenerate transmission in the Vedas of the Brahmins. This "genuine Veda" had once upon a time been brought to India, but subsequently the Indians had forgotten it and instituted the false Veda that is now religiously followed. The common aim of de Nobili and of Chumontou was the restoration of the true, most ancient divine revelation (Veda) and the denunciation of the false, degenerated Veda that the Brahmins now call their own.

In the wake of Ricci in China and de Nobili in India, the desire to find and study ancient texts and to acquire the necessary linguistic skills to handle them was increasing both among China and India missionaries, and this desire was clearly linked to the idea of a common Ur-tradition and its local vestiges that could be put to use for "accommodation" or, as I prefer to call it, "friendly takeover." What we have observed in other chapters, namely, that religion is deeply linked to the beginnings of the systematic study of oriental languages and literatures, clearly also applies to India; and if such study produced wondrous Egyptian (Kircher) and Chinese figurist flowers in the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries, the heyday of India in this respect was yet to come.

Calmette's Veda Purchase

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, Europeans in search of humanity's oldest texts received some enticing news in letters by Jesuit missionaries in India. For example, on January 30, 1709, Pierre de la Lane wrote in a letter that Indians are idolaters but also have some books that prove "that they had antiently a pretty distinct Knowledge of the true God." The missionary went on to quote the beginning of the Panjangan almanac that, as we saw in Chapter I, was among the earliest materials that impressed Voltaire about India (Pomeau 1995:161). In John Lockman's English translation of 1743, this passage reads as follows:

I worship that Being who is not subject to Change and Disquietude; that Being whose Nature is indivisible; that Being whose Simplicity admits of no Composition with respect to Qualities; that Being who is the Origin and Cause of all Beings, and surpasses 'em all in Excellency; that Being who is the Support of the Universe, and the Source of the triple Power." (Lockman 1743:2.377-78)

Father de la Lane wrote that the majority of Indian books are works of poetry and that "the Poets of the Country have, by their Fictions, imperceptibly obliterated the Ideas of the Deity in the Minds of these Nations" (p. 378). But India also has far older books, especially the Veda:7

As the oldest Books, which contained a purer Doctrine, were writ in a very antient Language, they were insensibly neglected, and at last the Use of that Tongue was quite laid aside. This is certain, with regard to their sacred Book called the Vedam, which is not now understood by their Literati; they only reading and learning some Passages of it by Heart; and these they repeat with a mysterious Tone of Voice, the better to impose upon the Vulgar. (pp. 378-79)

Such mystery, antiquity, and potential orthodoxy whetted the appetite of Europeans with an interest in origins and ancient religion. After Abbe Jean-Paul Bignon had been nominated to the post of director of the Royal Library in 1719 and of the special library at the Louvre in 1720 (Leung 2002:130), he gave orders to acquire the Vedas. But this was easier said than done. In 1730 a young and linguistically gifted Jesuit by the name of Jean CALMETTE (1693-1740), who had joined the Jesuit India mission in 1726, wrote about the difficulties:

Those who for thirty years have written that the Vedam cannot be found were not completely wrong: there was not enough money to find them. Many people, missionaries, and laymen, have spent money for nothing and were left empty-handed when they thought they would get everything. Less than six years ago [in 1726] two missionaries, one in Bengal and the other one here [in Carnate], were duped. Mr. Didier, the royal engineer, gave sixty rupees for a book that was supposed to be the Vedam on the order of Father Pons, the superior of [the Jesuit mission of] Bengal. (Bach 1847:441)

But in the same letter Calmette announced that he was certain of having found the genuine Vedas:

The Vedams found here have clarified issues regarding other books. They had been considered so impossible to find that in Pondicherry many people could not believe that it was the genuine Vedam, and I was asked if I had thoroughly examined it. But the investigations I have made leave no doubt whatsoever; and I continue to examine them every day when scholars or young brahmins who learn the Vedam in the schools of the land come to see me and I make them recite it. I even recite together with them what I have learned from some text's beginning or from other places. It is the Vedam; there is no more doubt about this. (p. 441)

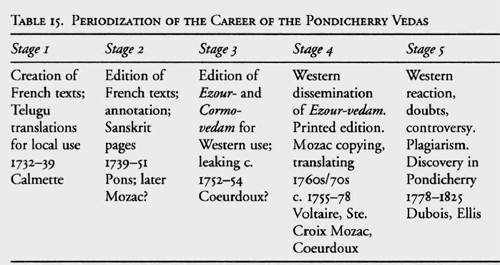

Calmette achieved this success thanks to a Brahmin who was a secret Christian, and in 1731 he reported having acquired all four Vedas, including the fourth that de Nobili had thought lost (p. 442). In 1732, Father le Gac mailed to Paris two Vedas written in Telugu letters on palm leaves, and the copying of the remaining two was ongoing (p. 442).

[W]hile Calmette did obtain the Rg, Yajur, and Sama Veda samhitas, his “Adarvana Vedam” is in fact an assortment of tantric and magical texts connected with goddess worship called Atharvanatantraraja and Atharvanamantraśāstra.

-- The Absent Vedas, by Will Sweetman

From the early 1730s Father Calmette devoted himself intensively to the study of the Vedas and wrote on January 24, 1733:

Since the King has made the decision to form an Oriental library, Abbe Bignon has graced us with the honor of relying on us for research of Indian books. We are already benefiting much from this for the advancement of religion; having acquired by these means the essential books which are like the arsenal of paganism, we extract from it the weapons to combat the doctors of idolatry, and the weapons that hurt them the most are their own philosophy, their theology, and especially the four Vedam which contain the law of the brahmins and which India since time immemorial possesses and regards as the sacred book: the book whose authority is irrefragable and which derived from God himself. (Le Gobien 1781:13.394)

The opponents in this combat were mainly Brahmins who considered the Europeans worse than outcasts. Calmette explained: "Nothing is here more contrary to [our Christian] religion than the caste of brahmins. It is they who seduce India and make all these peoples hate the name of Christian" (p. 362). The label Prangui, which the Indians first gave to the Portuguese and with which "those who are ignorant about the different nations composing our colony designate all Europeans" (p. 347), was a major problem from the beginning of the mission, and the Jesuits' Sannyasi attire and "Brahmin from the North" identity were in part designed to avoid such ostracism. The fight against the Brahmin "ministers of the devil" who "never cease to pursue their plan to ruin both our church and the Christians who depend on it" (p. 363) is featured prominently in Calmette's letters, and it is clear that the Frenchman meant business when he spoke about stocking up an arsenal of weapons especially from the four Vedas for combating these doctors of idolatry.

The preparation consisted in the intensive study of Sanskrit and a survey of India's sacred literature, in particular, of the Vedas.

The Veda has occupied an ambiguous position in Hinduism. On the one hand, many Hindus have proclaimed it their most authoritative and sacred body of literature. On the other, for the past two thousand years its contents have been almost completely unknown to the vast majority of Hindus, and have had virtually no relevance to their religious practices. In the last centuries before the Common Era, access to the Vedic texts was limited to male members of the three highest social classes, and since at least the second century CE, Hindu law-makers have declared that only male Brahmins are eligible to study the Veda. Between then and now, the great majority of the people we retrospectively identify as “Hindu” have been deliberately excluded from the Veda, and for most of this period we have little means of knowing whether such people accepted its authority. In ancient India, the maintenance of the Veda’s exclusivity was largely dependent on two factors: first, that it was prohibited to commit the Vedic texts to writing; second, that Brahmins were the guardians not only of the Vedas, but also of Sanskrit. By excluding all except male Brahmins from learning Sanskrit, the Veda was kept out of the majority’s reach. However, after the Sanskrit of the Vedas had developed, in the last centuries BCE, into the distinct, post-Vedic “Classical Sanskrit”, the content of the Vedas became inaccessible even to many Brahmins. Already in the Mānavadharmaśāstra, a Brahminical text composed probably around the 2nd century CE (Olivelle 2004), there is a reference to Brahmins who recite the Veda but do not understand it, and ethnographies attest to the existence of such persons today. This neglect of the content of the Vedas, together with the sustained emphasis on their correct recitation, signals the prevalent belief that the sacredness of these texts is in their sounds rather than their meaning. Thus, to recite correctly, or to hear such a recital, is intrinsically efficacious.

-- A religion of the book? On sacred texts in Hinduism, by Robert Leach

Of course, Calmette was eager to find any possible allusion to Jesus and major events of the Old and New Testaments. He searched for textual traces of the deluge and asked himself whether Vishnu is Jesus, if Chambelam means Bethlehem, and if the Brahmins stem from the race of Abraham (pp. 379-85). But the study of Sanskrit was also useful for disputing with Brahmins and scholars:

Up to now we have had little dealings with this kind of scholars; but since they noticed that we understand their books of science and their Samouscroutam [Sanskrit] language, they begin to approach us, and because they are intelligent and have principles, they follow us better than the others in dispute and agree more readily to the truth when they have nothing solid to oppose it. (p. 396)

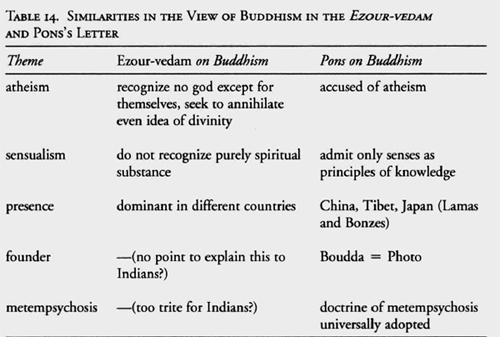

Naturally, Calmette profited from the experience of other missionaries who had mastered difficult languages and were interested in antiquity, for example, Claude de Visdelou who resided in Pondicherry for three decades and was very familiar with missionary tactics and methods in China.8 But even more important, in 1733 a learned fellow Jesuit by the name of Jean-Francois PONS (1698-1751) had joined Calmette in the Carnate mission. Pons and Calmette came from the same town of Rodez in southern France, had both joined the Jesuit novitiate in Toulouse, were both sent to India, and were both studying Sanskrit. Pons had arrived in India two years prior to Calmette, in 1724, and spent his first four years in the Carnate region. It was Pons who had tried to buy a copy of the Veda for 60 rupees in 1726, only to find out that he had fallen victim to a scam. From 1728 to 1733, he was superior of the Bengal mission, and it is during this time that he studied Sanskrit. As superior in Chandernagor he became an important channel for the European discovery of India's literature. He spent on behalf of Abbe Bignon and the Royal Library in Paris a total of 1,779 rupees for researchers, copyists, and manuscripts in Sanskrit and Persian. They included the Mahabharata in 17 volumes, 24 volumes of Puranas, 31 volumes about philology, 22 volumes about history and mythology, 7 volumes about astronomy and astrology, and 8 volumes of poems, among other acquisitions (Castets 1935:47). Though Pons was Calmette's junior by five years, he was thus more experienced and knowledgeable than his countryman when he joined the Carnate mission for a second time in 1733, and the two gifted missionaries could combine their efforts.

In 1735 Calmette described some of the benefits of the study of Sanskrit and the Vedas for his mission:

Ever since their Vedam, which contains their sacred books, has been in our hands, we have extracted texts suitable for convincing them of the fundamental truths that ruin idolatry; because the unity of God, the characteristics of the true God, salvation, and reprobation are in the Vedam; but the truths that are found in this book are only sprinkled like gold dust on piles of dirt; because the rest consists in the principle of all Indian sects, and maybe the details of all errors that make up their body of doctrines. (Le Gobien 1781:13.437)

Vedic Talking Points and Broken Teeth

From the early 1730s Calmette thus collected -- probably with the help of knowledgeable Indians and later of Pons -- examples of "fundamental truths" as well as "details of all errors" from the Vedas. This was the first systematic effort by Europeans to study such a mass of ancient Indian texts; and it was not an easy task because the language of these texts proved to be so difficult that even most Indians were at a loss:

What is surprising is that the majority of those who are its depositaries do not understand its meaning because it is written in a very ancient language, and the Samouscroutam [Sanskrit], which is as familiar to the scholars as Latin is among us, is not yet sufficient [for understanding] unless aided by a commentary both for the thought and for the words. It is called the Maha Bachiam, the great commentary.9 Those who make that kind of book their study are first-rate scholars among them. (p. 395)

At the time there were only six active Jesuit missionaries in the whole Carnate region around Pondicherry (p. 391), but they were assisted by many more Indian catechists who were essential for the mission. The missionaries could not personally go to some regions because of Brahmin opposition and other reasons, and to preach there was a main task of these catechists. Calmette's objective in studying the Vedas was not a translation of any part of them. That would definitely have been impossible after just a few years of study, even with the help of Pons. The language of these texts, particularly that of earlier Vedas, was a tough nut to crack even for learned Indians. In a letter dated September 16, 1737, Calmette wrote to Father Rene Joseph de Tournemine in Paris:

I think like you, reverend father, that it would have been appropriate to consult original texts of Indian religion with more care; but we did not have these books at hand until now, and for a long time they were considered impossible to find, especially the principal ones which are the four Vedan. It was only five or six years ago that, due to [the establishment of] an oriental library system for the King, I was asked to do research about Indian books that could form part of it. I then made discoveries that are important for [our] Religion, and among these I count the four Vedan or sacred books. But these books, which even the most able doctors only half understand and which a brahmin would not dare to explain to us for fear of a scandal in his caste, are written in a language for which Samscroutam [Sanskrit], the language of the learned, does not yet provide the key because they are written in a more ancient language. These books, I say, are in more than one way sealed for us. (Le Gobien 1781:14.6)

But Calmette tried his hand at composing some verses in Sanskrit and wrote on December 20, 1737, after a bout of fever that had hindered his study of Sanskrit: "I could not help composing a few verses in this language, in the style of controversy, to oppose them to those poured forth by the Indians" (Castets 1935:40). Calmette was inspired by de Nobili's writings that were stored at the Pondicherry mission and seems to have partly copied and rearranged de Nobili's Sattia Veda Sanghiragham (Essence of genuine revelation) (p. 40), whose title expresses exactly the idea that seems to have influenced Calmette so profoundly: the notion of a true Veda (satya veda).

Unlike de Nobili who had thought that the fourth Veda was lost and had presented himself as the guru who brought at least its teaching back to India, Calmette had also bought the fourth Veda10 [In his letter of September 17, 1735, Calmette describes this Veda as "The Adarvanam, which is the fourth Vedam, and teaches the secret of applying magic" (Le Gobien 1781:13-420).] and found that it was far more readable and therefore of somewhat later origin:

[W]hile Calmette did obtain the Rg, Yajur, and Sama Veda samhitas, his “Adarvana Vedam” is in fact an assortment of tantric and magical texts connected with goddess worship called Atharvanatantraraja and Atharvanamantraśāstra.

-- The Absent Vedas, by Will Sweetman

There are texts that are explained in their theology books: some are intelligible for a reader of Sanskrit, particularly those that are from the last books of the Vedan, which by the difference of language and style are known to be more than five centuries younger than the earlier ones. (Le Gobien 1781:14.6)

Even if the Vedas remained for the most part a sealed book for Calmette and Pons, they could make a survey of their contents and pick out certain topics, stories, and quotations that could be used as talking points in debates and serve as "weapons" in the missionary "arsenal." One goal of such a collection of "truth" and "error" passages drawn from the Veda was their use in public disputes against Brahmins. A favorite tactic mentioned by Calmette is the following:

Another way of controversy is to establish the truth and unity of God by definitions or propositions drawn from the Vedam. Since this book is among them of the highest authority, they do not fail to admit this. Following this, it is very easy to reject the plurality of gods. Now if they reply that this plurality is found in the Vedam, which is true, it is confirmed that there is a manifest contradiction in their law as it does not accord with itself. (Le Gobien 1781:13.438)

The verbal operations in such writing as Patai's (who has outstripped even his previous work in his recent The Arab Mind 134 [The Indian Mind] ) aim at a very particular sort of compression and reduction. Much of his paraphernalia is anthropological -- he describes the Middle East [India] as a "culture area" -- but the result is to eradicate the plurality of differences among the Arabs [Indians] (whoever they may be in fact) in the interest of one difference, that one setting Arabs [Indians] off from everyone else. As a subject matter for study and analysis, they can be controlled more readily. Moreover, thus reduced they can be made to permit, legitimate, and valorize general nonsense of the sort one finds in works such as Sania Hamady's Temperament and Character of the Arabs [Temperament and Character of the Indians]. Item:

The Arabs [Indians] so far have demonstrated an incapacity for disciplined and abiding unity. They experience collective outbursts of enthusiasm but do not pursue patiently collective endeavors, which are usually embraced halfheartedly. They show lack of coordination and harmony in organization and function, nor have they revealed an ability for cooperation. Any collective action for common benefit or mutual profit is alien to them.

The style of this prose tells more perhaps than Hamady intends. Verbs like "demonstrate," "reveal," "show," are used without an indirect object: to whom are the Arabs [Indians] revealing, demonstrating, showing? To no one in particular, obviously, but to everyone in general. This is another way of saying that these truths are self-evident only to a privileged or initiated observer, since nowhere does Hamady cite generally available evidence for her observations. Besides, given the inanity of the observations, what sort of evidence could there be? As her prose moves along, her tone increases in confidence: "Any collective action ...is alien to them." The categories harden, the assertions are more unyielding, and the Arabs [Indians] have been totally transformed from people into no more than the putative subject of Hamady's style. The Arabs [Indians] exist only as an occasion for the tyrannical observer: "The world is my idea."

-- Orientalism, by Edward W. Said

Calmette described various dispute strategies that are based on the knowledge of the Vedas and address themes such as the concept of a world soul, punishment in hell, and reward in paradise. (pp. 445-50).

Like de Nobili, Calmette thought that the word "Veda" referred to the divinely revealed "word of God" and explained: "I translated the word Vedam by divine scriptures [divines Ecritures] because when I asked some brahmins what they understood by Vedam, they told me that for them it means the word of God" (p. 384). But if this was God's revelation, then it had been incredibly corrupted. The best proof of this was that Calmette had to look so hard for those little specks of gold. The more he studied, the clearer it must have become to him that de Nobili had been right in concluding that the Indian Veda was far removed from the "genuine Veda" or satya vedam, that is, the divine revelation to the first patriarchs. That true Veda had been disfigured in India and needed to be restored to its ancient glory. It is for this purpose that Calmette collected both the specks of gold and the worst symptoms of degeneration in the Veda. In the quoted example, the unity and goodness of God were first confirmed on the basis of Vedic passages and then contrasted with very human failings and even crimes of Indian gods like Shiva and Vishnu. In this manner an inner contradiction of the Veda could be exposed, and the opponents in the debate who could not deny the accuracy of the quotations from the Vedas could be caught in a no-win, "heads I win, tails you lose" type of situation.

Such tactics thus required intensive study of Indian sacred scriptures. Since the Indian catechists were almost never from the Brahmin caste, they were at best familiar with some puranic literature but certainly not with the Vedas. But since they most often had to conduct the debates, the quotations from the Vedas and talking points had to be set in writing; and because the disputes were held in front of ordinary people, such texts and quotations needed to be in Telugu rather than Sanskrit. In the Edifying and curious letters there are many examples of disputes involving catechists; but one of them is of particular interest here since it features a catechist who used exactly the kind of text that could have resulted from Calmette's "talking points" effort. The letter by Father Saignes is dated June 3, 1736, a couple of years after the acquisition and copying of the Vedas, and it stems from the very region in which Calmette worked:

A brahmin, the intendant of the prince, passed through a village of his dependency and saw several persons assembled around one of my catechists who explained the Christian law to them. He stopped, called him, and asked him who he was, of what caste, what job he had, and what the book which he held in his hand was about. When the catechist had answered these questions, the brahmin took the book and read it. He just hit upon a passage which said that the gods of the land are no more than feeble men. "That's a rare teaching," said the brahmin, "and I would like you to try to prove that to me." "Sir," replied the catechist, "that will not be difficult if you order me to do so." "If that's all you need then I order you," rejoined the brahmin. The catechist began to recite two or three events from the life of Vishnu, which were theft, murder, and adultery. The brahmin wanted to change the topic [detourner le discours]; but the catechist would not let him and pressed on even more. The brahmin realized too late that he had become caught in a dispute without paying attention to his status as a brahmin; and not knowing how to extricate himself honorably from this affair, he flew into a violent rage against the Christian law. "Law of Pranguis," he said, "law of miserable Parias, infamous law." "Permit me to say this," said the catechist, "the law is without stain: the sun is equally worshipped [adore] by the brahmins and the Parias, and it must not be called the sun of the Parias even though they worship it just as the brahmins do." This comparison enraged the brahmin even more and he had no other response than to hit the catechist several times with his stick. He also hit him on the mouth and shattered all his teeth, and he had him chased out of the village like a Parias, prohibiting him ever to come there again and ordering the villagers to never give him shelter. (Le Gobien 1781:14.29-30).

Father Saignes wrote that this catechist "explained the Christian law" to his local audience and that for this purpose he used a "book" that one could practically open at random and hit upon a passage that says that "the gods of the land are no more than feeble men." Was this a praeparatio evangelica type of work that denounces the reigning local religion (see Chapter I) in order to prepare the people for the Good News of the Christians? At any rate, it must have been a book in Telugu whose content stemmed from the Carnate missionaries who intensively studied the local religion and prepared such materials for the catechists. All this would seem to point to Father Calmette and Father Pons who at that very time (in the mid-1730s) and in that very region devoted much time to the study of the sacred scriptures of India.

We do not know what book the catechist read, but to my knowledge, the only extant text that would fit the missionary's description is the Ezour-vedam. A Telugu translation of this text must have existed since both Anquetil-Duperron's and Voltaire's Ezour-vedam manuscripts contain the following passage:

Biache. I would now be interested in knowing the names of the different countries inhabited by people and the differences among them. You have told me about heaven and hell. Give me a brief description of the earth which brings me up to date on all the different countries that are inhabited.

Chumontou responding to the question tells him the names of the different countries he knew and marks their location for him. Those interested can find them on the other page in the Telegoa language.11

Apart from indicating that the Ezour-vedam's original French text had been translated into Telugu and was illustrated with a map, this passage is also extremely significant because it shows that the Ezour-vedam was designed for use by missionaries or catechists in the region where Telugu is spoken. It is one of two passages in the book that betrays the book's intended use. The target audience must have spoken Telugu, and the content of the map must have conveyed not classical Indian geography but rather a more correct and modern vision of the world and its countries. World maps played an important role in the Christian mission since the vast advantage in knowledge they embodied could boost the claim of expertise about other unknown regions such as heaven and hell. Ricci's world maps created quite a sensation in China but I ignore if seventeenth-century world maps from the Indian missions are extant in some Indian or Roman archives.

Thus a Telugu version of the Ezour-vedam could very well have been in the hands of that catechist. Opening the Ezour-vedam at random, one may indeed hit upon some passage that could enrage a Brahmin. For example,

Are you stupid enough to overlook even what is right there before your eyes? What you say about the inhabitants of the air is completely insane! How can beings born of a man and a woman and therefore with a body like us live in the air and keep afloat? ... There is only one god, and there has never been any other; this god is not born from Kochiopo, and those who are born from him were never gods. They are all simply men, composed of a body and a soul like us. If they were gods, they would not be numerous, one would not have seen them getting born, and they would not be subject to death. (Rocher 1984:161-62)

There are many other pages in the Ezour-vedam that more or less fit the missionary's description, but the following example may suffice to make the point: "I will not stop, however, to repeat and tell you that Brahma is no God at all, that Vishnu is no God either, and neither are Indra and all the others on whom you lavish this name; and Shiva, finally, is no God either, and even less the Lingam" (p. 180).

The speaker of these words in the Ezour-vedam, Chumontou, uses a method that strangely resembles Calmette's: "in order to instruct people and save them," Chumontou examines common features of Indian religion such as the "different incarnations" of its gods and "refutes them through the words of the Vedan" (p. 135) -- the very "weapons" that, according to Calmette who was proud of this method, hurt the Brahmins most. But there is another feature that links Calmette to the Ezour-vedam and the other texts found by Francis Ellis in 1816 among the remains of the Jesuit library at Pondicherry: his overall view of the Vedas.