Chapter 20: Corroboration and New Evidence: November 1992I INTERVIEWED PHOTOGRAPHER JOHN "BILL" McAFEE, who in 1968 was covering Dr. King's involvement with the garbage strike on network assignments. McAfee set up his camera at the Lorraine just before noon on April 4, noticing as he arrived MPD chief J. C. MacDonald "lurking" around the Butler Street driveway entrance of the Lorraine, walkie-talkie in hand. He recognized MacDonald, having photographed him many times, and he was surprised to see him since the chief rarely left his office.

McAfee left the Lorraine at around 5:00 to drive the reporter he was working with to the airport. Waiting for him at home there was a message from ABC assigning him to cover the immediate aftermath of the assassination. He bolted out the door and drove back to the South Main Street area, stopping briefly to pick up a sound man and some equipment at his brother's audio shop on Second Street, one block from Mulberry Street.

As he entered the shop he heard the local AM station actually being overridden by a powerful CB broadcast. He realized that in order for this to occur the CB broadcast must have been transmitting from a base in the immediate area. What he heard was the hoax broadcast, and this was the first time there had been any indication that it might have originated from the immediate vicinity of the shooting.

I subsequently called Carroll Carroll, who confirmed that for a CB transmission to override an AM signal it had to originate close to the receiving set. Thus the possibility that the broadcast was a prank carried off by a CB hoaxer in a distant part of the city, as had been concluded by the MPD, made no sense.

McAfee was willing to testify.

***

IN LATE OCTOBER AND EARLY NOVEMBER, with the help of Sarah Teale of Teale Productions, I visited CBS, NBC, and ABC studios in New York to view all the available library film taken at that time. I was most interested in Earl Wells's NBC interview with gas station attendant Willie Green, as well as in locating photographs of the bush area behind the rooming house before it was cut.

Ernest Withers, a black Memphis photographer, also agreed to provide contact sheets of photographs of the scene at the time. In addition. he agreed to attempt to identify and locate a black woman who was a senior at LeMoyne College in the spring of 1968 who was referred to in Hugh Stanton's investigation notes as allegedly seeing a man (possibly, I thought, the same person described by Solomon Jones) leaving the scene right after the shooting. The young woman apparently screamed at the police to go after the man.

Neither Teale nor Withers was able to produce any clear photographs of the bushes taken on the day of the shooting, nor was Withers able to locate the LeMoyne student. I also tried to find Mary Hunt who was in the Joseph Louw photograph of the people on the balcony pointing in the direction of the back of the rooming house. She appeared to be focusing her gaze on some point further to her left (south) than the others. I eventually discovered that she had died of cancer.

One of our priorities was to gain a conclusive understanding of what happened to the backyard area of the rooming house. By 1992 the area was vastly different from the way it was in 1968. Then, the common backyard area of the connected wings of the rooming house led to a four-foot-wide alley running to a door that led down to the basement and, from the inside landing to the right, into Jim's Grill.

The backyard sloped slightly downward toward a high wall (about 7'6"-8') rising from the Mulberry Street sidewalk. As mentioned previously, the area closest to the wall was engulfed with a thicket of untamed mulberry bushes, small trees of up to twenty-five feet in height, untended grass and weeds, and a tall sycamore tree. The thick bushes extended for some distance from the wall back into the yard.

We needed to interview as many people as we could who remembered the yard at the time. Wayne Chastain had gone up to the second floor of the rooming house on April 4 shortly after the shooting to get a view of the bushes and the backyard. He said he looked through the Stephens's kitchen window and saw a very thick growth of bushes and brush.

Press Scimitar reporter Kay Black repeated what she had told me in 1978 about the telephone call she received on April 5 from former mayor William Ingram, in which he said that there was a work crew behind the rooming house cutting down all the bushes and high brush and grass in the area. Ingram appeared to be suspicious of the purpose behind this activity.

Later that morning, Black went over to the area and saw that the cutting and clearing had been completed. The bushes were gone, the brush was removed and debris was neatly raked and stacked in piles. No satisfactory reason was ever given to her, although there was some mention of a concern that tourists not be offended. Black agreed to testify. (SCLC field organizer James Orange had noticed the bushes at the time of the shooting and that they were gone the next morning. I made a mental note to contact him.)

Cab driver James McCraw, who was familiar with the area and went out there occasionally through the rear door of the grill, said it was completely overgrown and never cared for or tended at all. While not knowing the exact time, McCraw did recall that the area was cut and cleaned by the city shortly after the shooting.

Former MPD captain (lieutenant in 1968) Tommy Smith who had refused for a very long time to be interviewed, finally agreed. In our 1992 meeting he vividly remembered the state of overgrowth in the rooming house backyard. He described a "thicket" of mulberry bushes, which impeded him considerably as he attempted to gain access on the evening of the shooting.

As to the presence of a person in the bushes, Earl Caldwell agreed to testify at the trial. I believed that the defense had found in him the strongest available witness that the shot had come from the brush area behind the rooming house. We were still looking for Solomon J ones, who had been away from Memphis for a number of years. It was rumored that he was in Atlanta, and since he had previously worked for funeral homes we began to check out the funeral homes there.

***

HAVING LEARNED ABOUT THE FOOTPRINTS near the top of the alleyway between the two buildings and that three patrolmen had been in that area shortly after the shooting, I had been trying to locate the only one who was still alive -- dog officer J. B. Hodges. He had long ago moved from Memphis out into the country. Since he had been in that area immediately after the shooting, I believed that if we could find him he would be able to give us a good description.

In addition, I wanted to locate Maynard Stiles, who had been deputy director of the Memphis City Public Works Department in 1968. Since he was in charge of day-to-day operations it was likely that he would have been responsible for giving the orders for any cutting and cleanup activity.

***

IT HAD OFTEN BEEN RUMORED that a tree branch was cut some time shortly before April 4. Jim Reid, the former Memphis Press Scimitar reporter/photographer who had told me fourteen years earlier that he had taken a picture of the cutting, was still unable to come up with the photograph.

After many attempts, on November 30 I caught up with Captain Ed Atkinson, who in 1968 had been a staff assistant to Memphis fire and police director Frank Holloman. I thought that he might have seen or had access to some significant documentation. He didn't, but he remembered being present in the aftermath of the killing at a discussion in police headquarters with two other officers. One of the officers said that he was present with two FBI agents at the bathroom window at the rear of the rooming house after the killing; one of the agents said that a tree branch would have to be cut, because no one would ever believe that a shooter could make the shot from that point with the tree in the way. The branch was cut down the next day. Atkinson didn't remember who the officers were.

Weeks later, Atkinson underwent hypnosis to enhance his memory. For some time he described two featureless faces, though he said one of the voices sounded familiar. Slowly he began to recognize the owner of the familiar voice and he identified him as Earl Clark (an MPD captain). Then he discerned that the other officer who was recounting the conversation he had witnessed was a sergeant. He wasn't able to identify him, though he described him as wearing thick-rimmed glasses, and having a moustache.

***

EVEN THOUGH JAMES NEVER DENIED BUYING THE GUN found in the bundle in front of Canipe's, we obviously needed to learn as much as possible about that purchase.

When Ken Herman interviewed Aeromarine Supply store manager Donald Wood in his Birmingham store, Mr. Wood more or less repeated his statements to the HSCA, saying that the buyer, whom he photo-identified as James Earl Ray, knew nothing about guns. He added that the buyer said he was going deer hunting in Wisconsin with his brother-in-law. Then, curiously enough, he volunteered that he had always believed that one of his customers, a Dr. Gus Prosch, was somehow involved in the killing. He said that Prosch had bought a lot of guns from him, was involved with gun dealings, and had also been involved in racial problems. When, months later, I interviewed Wood he confirmed his earlier statement to my investigator. Prosch's name had surfaced on the periphery of the case before, in the affidavit of Morris Davis. We knew that for some reason his fingerprints had been compared by the FBI with some of the unidentified prints in this case with no success. Prosch had rebuffed Herman's earlier attempt to interview him. Subsequently, I extensively interviewed Prosch, alone and in Morris Davis's presence. He categorically denied any involvement.

I also instructed Herman to try to confirm James's movements between March and April 1, 1968, since I believed that the prosecution was going to contend that he had stalked Dr. King in Atlanta during that time. The motels James said he had stayed in on his trip from Birmingham to Memphis either no longer existed or had long ago discarded their records. We met similar frustration in Atlanta where potential witnesses were either dead or missing.

Jim Kellum, a local investigator, had at my request developed a file on topless-club owner Art Baldwin, who had been named by inmate Tim Kirk as the person who put out the contract on James in June or July 1978. Kellum's documents independently confirmed Baldwin's connections with organized crime through mob leader Frank Colacurcio in Seattle and Carlos Marcello in New Orleans, as well as his role as an informant and witness for the federal government against Tennessee governor Ray Blanton and members of his staff.

Kellum, however, had no success in arranging access to produce man Frank Liberto's mistress, or in pinpointing information about his organized crime associates referred to by writer William Sartor.

Then suddenly, on November 17, 1992, Kellum asked to be released of any further work, saying some of his contacts weren't taking kindly to the thrust of my investigation. I understood. I discreetly approached private investigator Gene Barksdale, who had been close to the Liberto clan, for information on Frank Liberto's activities. I pressed him to talk to Liberto's mistress and for information on Liberto's organized crime associates, one of whom, Sam Cacamici, I learned had died. Barksdale told me that some of his old friends in the Liberto family started behaving strangely when he approached them on these issues. He also got no cooperation from the mistress in his initial efforts.

The investigation of the Liberto connections to the killing was complicated by the fact that in 1968 there were no fewer than three Frank Libertos in Memphis alone, each with extended family connections in New Orleans. The first Frank Liberto (Frank Camille Liberto), the primary target of the investigation, was the produce dealer overheard by john McFerren who died in 1978. The second Frank Liberto had also been dead for over ten years. In 1968 he owned Frank's liquor store and the Green Beetle Tavern on South Main Street, just up the block from Jim's Grill. The third and probably wealthiest Frank Liberto was over 80 in 1992. Barksdale told me that despite his age he was still active in his automobile business. So in 1968 we had no fewer than three Frank Libertos with some, as yet unclear, family relationship. There was also another member of the Liberto family, apparently related to Frank C. Liberto, who owned and ran a business a short distance from the Lorraine.

John McFerren told me about Ezell Smith, who worked for this business and around the time of the assassination saw a rifle being put together there. McFerren said Ezell learned later that this was the gun used to kill Martin Luther King.

As noted earlier, in 1978 I had somehow acquired a photograph of a building with a note along the top margin indicating that a building within blocks of the scene of the crime owned by a relative of an organized crime figure, was where the rifle bought by Ray was stored until April 4, 1968.

Ken Herman photographed the building where Ezell had worked. It was the same building as in the photograph sent to me. I saw this as the first crack in the silence that kept closed the involvement of local organized crime in the killing. We looked for Ezell, without success. The frustration of not being able to capitalize on such a tip was overwhelming.

***

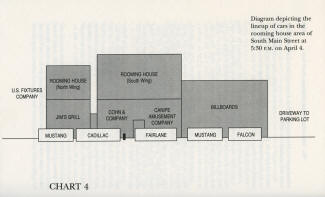

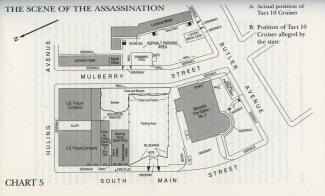

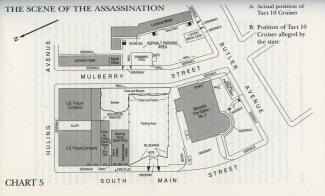

WE NEXT SOUGHT OUT Emmett Douglass, the policeman whose car the MPD report states spooked James as he allegedly fled. The MPD report concluded that he entered the sidewalk looking south on South Main Street and saw Douglass's "emergency cruiser" parked near the sidewalk at the north front side of the fire station. At that point he supposedly panicked, throwing the bundle down in Canipe's recessed doorway before driving away in the Mustang parked nearby.

The HSCA report hedged. It stated that James probably saw the Douglass cruiser that was parked "adjacent" to the station and pulled up to the sidewalk (a physical impossibility since the front of the station was set back about sixty feet from the sidewalk) or possibly saw policemen exiting from the fire station.

A TACT 10 cruiser driven by Emmett Douglass was indeed parked at the north side of the fire station but not near the sidewalk. Douglass was sitting in the station wagon monitoring the radio during the break that afternoon, while the other members of his unit were in the fire station.

On a chilly late November evening, Captain Douglass went with me to the fire station and showed me exactly where he was parked late in the afternoon of April 4, 1968. He insisted that he was not parked up to the sidewalk but was directly in front of the northwest side door of the station about sixty feet back from the sidewalk of South Main Street. (See Chart 5, p. 215.) In 1968, a set of billboards with frames that extended from the ground to a considerable height were located on the north side of the parking lot, right next to the rooming house building. These structures would have blocked the view of anyone looking toward his position from that spot.

It was rumored that there had also been a hedge that ran between the edge of the fire station driveway and the parking lot next door extending out to the sidewalk, which would have impeded the view of anyone looking from the sidewalk near Canipe's to the spot where the MPD alleged that Douglass's car was parked. If the rumors were true that the hedge had been cut down soon after the shooting, it could have been done to bolster the MPD claim that James was frightened upon seeing the police wagon parked near the sidewalk.

Douglass told me that he never told the MPD or the FBI that he was parked up near the sidewalk; it would have made no sense for him to park up where he would have obstructed both pedestrian and incoming vehicular traffic. By parking farther back alongside the building and opposite the door, he was out of the way yet readily accessible to his TACT unit fellow officers in the event of an emergency.

CHART 5: THE SCENE OF THE ASSASSINATION

CHART 5: THE SCENE OF THE ASSASSINATIONAfter the shot, Douglass got out of the car and began to run toward the rear of the station, but, remembering his radio duty, he returned to the car and called in to headquarters. Others had exited the station through the northeast side door and went over the low fence and wall. Douglass remembered two officers, one with a gun drawn, running from the front of the station, crossing his line of vision about sixty feet in front of him within a minute of the shooting. If he had been parked up near the sidewalk, they would have passed very close to the front of his car. They were nowhere near him.

Douglass agreed to testify.

***

FORMER FBI AGENT ARTHUR MURTAGH, who had testified before the HSCA as to the bureau's extensive COINTELPRO activities against Dr. King, agreed to take the stand. His profound disillusionment over the bureau's disregard for the Constitution and his first-hand knowledge of the bureau's illegal activities against Dr. King made Murtagh an invaluable asset to the defense.

***

WHEN I HAD BEGUN MY EXAMINATION OF THE FILES in the attorney general's office in the Criminal Justice Center Building, Investigator Jim Smith was assigned to assist me. He had a long-term interest in the case, and his assistance proved to be of immeasurable value. Gradually, Smith began to talk about his experiences in 1968.

As a young policeman, he attended a clandestine training course run in Memphis. It covered such activities as riot control and physical and electronic surveillance techniques. The sessions began in late 1967 and were conducted in strict secrecy by federal trainers paid by one or another federal agency. None of the Memphis participants understood why the training was necessary, because Memphis had never experienced the type of riots seen in other cities. The events of early 1968, like a self-fulfilling prophecy, caused some of those select Memphis policemen to rethink their reactions at the time. Perhaps Holloman knew something that they didn't. Some of this training was conducted in secret facilities, the location of which was not even known by the participants, who were picked up at police headquarters and driven in a van (from which it was not possible to see outside) directly inside the training facility somewhere in Memphis. The Memphis officers couldn't understand the reason for the cloak and dagger behavior. It occurred to me that these were typical of the training sessions mentioned earlier that the CIA conducted during this period for selected city and county police forces. Such sessions were coordinated by its Office of Security (OS), often in conjunction with the FBI and army intelligence which had similar programs.

Smith also told me of a shadowy federal contract agent who was assigned to run some of these sessions. Cooper, who went by the name of Coop, arrived in January 1968. Jim thought it strange that, unlike the other trainers, Coop didn't stay at an up-market hotel but rather at the Ambassador Hotel on South Main Street, in the area of Jim's Grill. He remembered meeting Coop at Jim's Grill, in the Arcade Restaurant, and at the Green Beetle. When Smith asked why he "hung out" in such places, Coop replied that this was where he had to go to get information he needed. Coop drew detailed maps of the area, and told Smith that he was with army intelligence before he became an FBI agent. He had been dismissed because of a drinking problem, and he seemed to drift into this contract work. It occurred to Smith that Coop was really on some sort of intelligence gathering mission and that the training activity was a cover.

Coop dropped out of sight just before the assassination. Smith never saw him again.

Since there was considerable confusion about where Dr. King stayed in his previous trips to Memphis, I asked Jim Smith what he knew. He knew that on at least one occasion -- the evening of March 18, 1968 -- Dr. King stayed at the Rivermont. Smith knew this because he was assisting a surveillance monitoring team. The unit operated with the collaboration of the hote,1 and placed microphones throughout the suite. The conversations in Dr. King's penthouse suite were monitored from a van parked across the street from the hotel. Since Smith hadn't placed the devices he didn't know exactly where they were. Another source -- who must remain nameless -- described the layout to me. Every room in Dr. King's suite was bugged, even the bathroom. My source said they had microphones in the elevators, under the table where he ate his breakfast, in the conference room next to his suite, and in all the rooms of his entourage. Even the balcony was covered by a parabolic mike mounted on top of the van. That mike was designed to pick up conversations without including a lot of extraneous noise because it used microwaves that allowed it to zero in on conversations.

The surveillance team had about a dozen microphones -- "bugs" -- each transmitting on a different frequency, which prevented feedback. The multiple bugs enhanced the recording by providing a stereo effect, which was a trick allegedly learned from the movie industry. There was a repeater transmitter mounted on top of the hotel, which picked up each transmission and relayed it to one of the voice-activated recorders in the van. The recorders were all labeled according to where their respective bugs were located, and a light on the control panel came on when activity was being recorded from a particular bug. The person monitoring listened to it for a moment to decide whether something was being said that needed to be reported immediately. If it didn't seem urgent, it was simply recorded and at the end of the shift it was sent to the office to be transcribed and filed for future reference.

The surveillance detection equipment generally available wasn't sophisticated enough to pick up the bugs used, because they emitted a very weak signal. In fact, they transmitted the signal only about forty or fifty feet, to the rooftop repeater. My source said that there was nothing on the market at that time that would allow them to pick up such a weak signal.

The source said the repeater on the roof picked up the weak signal and amplified it many times before transmitting it to the van. Since the bugs could transmit about fifty feet and the ceilings in King's suite were about eight feet high with the repeater directly above them, there was forty feet or so to spare.

If Dr. King hadn't been on the top floor, the repeater would have been placed in the room directly above him or in one of the rooms on either side of his room.

I was advised that this surveillance effort wasn't undertaken to learn about Dr. King's strategies. The intelligence operation was mounted to catch him in sexually compromising situations which could be exploited at the right time.

At the time of the surveillance Jim Smith was detailed to special services and assigned to the MPD intelligence bureau. He said he actually acted as a gofer for the two federal agents who ran the surveillance and manned the headphones. They told him that they were instructed to obtain any incriminating information they could about Dr. King's personal activities, plans, and movements. They operated from a van parked near the hotel. This confirmed what I had suspected for years.

Dr. King also stayed at the Rivermont on the night of March 28, just after the march. As mentioned earlier, he was routed there by the MPD, led by motorcycle lieutenant Marion Nichols, who also arranged for his suite. Although Smith wasn't detailed to the surveillance team on that evening, it is reasonable to assume that the same surveillance program was in effect.

Smith, of course, was aware that the bureau had electronically surveilled Dr. King all over the country, and he quite rightly believed that these activities were no longer a secret. He may not have appreciated that the bureau had always denied there had been any electronic surveillance in Memphis. Illegal electronic surveillance conducted so close to the time of the assassination wasn't an operation with which the bureau would want to be associated. At the time Smith and I assumed that the surveillance was being conducted by the FBI, because the operation appeared to have their "M.O." stamped all over it.

I now understood why Dr. King was routed to the Rivermont on March 28 (where he had no reservation) instead of the Peabody (where he was supposed to stay that evening). The change had never made sense to me because the Peabody was sufficiently removed from the violence and was accessible. Lt. Marion Nichols wasn't available for an interview at any time before the trial. When interviewed subsequently he denied any personal or departmental responsibility for the decision to go to the Rivermont, stating that it was a decision made by someone in Dr. King's party.

After checking with his chief, Fred Wall, who had no idea what he would say but told him to go ahead and just tell the truth, Jim Smith agreed to testify.

Smith also recalled the outbreak of violence in the march of March 28 when he was part of a phalanx of police officers stretching across South Main Street at McCall as the marchers came up Beale Street. He said that he and his fellow officers were told not to break ranks even though some isolated individuals between them and the main line of the march began to break windows.

The violent disruption of that march was of interest because there were indications that provocateurs were present. This was the only violent march ever led by Dr. King, the violence coming apparently from within the group itself. It necessitated his return to Memphis on April 3, when he was moved to a highly visible accommodation in a most vulnerable motel where he wouldn't normally have stayed.

Rev. Jim Lawson's recollections dovetailed with Jim Smith's. He remembered leading the marchers up Beale Street and out to Main, where they were confronted by riot police. This was ominous in itself to those committed to a peaceful march, but then Lawson saw a group of youths on the sidewalk in the area between the marchers and the police. He knew the Invaders and most of the other young black activists but did not recognize any of these youths as being from Memphis. They had begun to break shop windows, yet the police remained impassively in place, just watching.

Lawson knew then that the police were going to use the gang activity as a justification to turn on the marchers. He stopped the march and tried to turn the line around, worried as much about Dr. King's safety as anything else. King didn't want to leave but eventually let himself be spirited away by Bernard Lee and Ralph Abernathy.

On another tack Jim Lawson agreed to travel to Washington to speak with Walter Fauntroy, intending to explore the entire HSCA investigation with him, and assess his willingness to help. Lawson and I agreed to meet in Memphis in late December.

***

THE DEFENSE HAD TO BE CONCERNED about the statement of the prosecution's only eyewitness. Under our rules of procedure, in Stephens's absence his official statement could be read into the record. His drunkenness wouldn't be evident in a statement taken after the event. He would have to be impeached.

I saw Grace Walden, Stephens's common-law wife, on November 29 at the convalescent home where she now lived. She again confirmed that Charlie Stephens was drunk on the afternoon of April 4 and that he didn't see anything. This corroborated information already gathered through interviews with Wayne Chastain, MPD captain Jewell Ray and homicide detective Roy Davis and his partner, lieutenant Tommy Smith. Captain Ray had gone into the rooming house before 6:30 p.m. He was unable to interview Charlie Stephens because he was so drunk. Detective Davis tried to interview Stephens that evening too but also found he was simply too drunk, and lieuten ant Smith confirmed that he had tried to interview Stephens on that evening but found him incoherent and barely able to stand up.

Tommy Smith offered another unsettling revelation relating to a photograph I found in the attorney general's file showing a lump just below Dr. King's shoulder blade. It appeared to be where the death slug had come to rest just under the skin (see photograph # 16.) Smith confirmed that fact and said that he pinched the skin and rolled what appeared to him to be an intact slug beneath his fingers. He said that at the time he was certain they had a good evidentiary bullet.

The death slug in the clerk's office was in three fragments and the official story that had evolved was that it had always been in three fragments. However, in the HSCA volumes there was a photograph of the slug, apparently taken at the time of removal by Dr. Francisco, showing it to be in one piece at that point. Francisco's report referred to a single slug.

* * *

WHEN I INTERVIEWED CAPTAIN JEWELL RAY I told him that I had noticed in one report that he had met with an army intelligence officer named Bray on the evening of the murder. He confirmed the meeting. He said that Bray was the liaison with the Tennessee National Guard.

Jewell Ray was Lt. E. H. Arkin's superior in the MPD intelligence bureau. He said that Arkin was so close to the FBI that he (Jewell) locked his desk drawer to prevent documents from being routinely turned over to Bill Lawrence of the local FBI field office. Captain Ray resented the FBI's practice of taking everything and giving little or nothing in return. Arkin wouldn't agree to be interviewed before the trial.

***

CALVIN BROWN HAD LIVED AT THE LORRAINE after the assassination. I asked Ken Herman to locate him to see if he knew or heard anything during that time about the death of Mrs. Bailey or the killing itself. I eventually interviewed him sitting in Herman's car in front of Brown's house. Brown surprised me by declaring that he had heard that Jowers, the owner of Jim's Grill, did it. He couldn't recall the source of his information.

***

I LOCATED A TELEPHONE REPAIRMAN named Hasel Huckaby who according to a supplement to the MPD report was working near the scene of the crime on April 4. Huckaby said that on April 4 he and his partner, Paul Clay, were assigned to complete some work at Fred P. Gattas's premises on the corner of Huling and South Main Streets. At one point Huckaby noticed a well-dressed though apparently intoxicated person sitting on the steps by a side entrance of Gattas's place on Huling. Parked across the street was a plain dark-blue sedan that Huckaby associated with the man. Huckaby said that the man would occasionally stagger over to him and pass some inane remark. He felt there was something phoney about the person. He was too well-dressed for the neighborhood and his behavior didn't ring true.

The man was still there when Huckaby and Clay left late that afternoon. Huckaby gave a routine statement following the assassination but was puzzled as to why MPD detective J. D. Hamby wanted him to detail each minute of his working assignments for a period of two weeks prior to the day of the assassination. About five years later, he was working on a line in the central headquarters of the police department when he saw Lt. Hamby. On impulse he asked Hamby if he had ever found out who the "drunk" was whom he saw on April 4, 1968. He was told that the man's name was Smith and that he was really an FBI agent under cover. If true, this was the first indication of an FBI presence at the scene prior to the shooting.

Apparently this was information that Huckaby shouldn't have learned -- later he received a package in the mail containing half a burned match, half of a smoked cigarette, and rattles from a rattlesnake. After asking around, he came to believe that this parcel was a threat; a warning for him to keep his mouth shut about what he had learned if he wanted to finish the rest of his life. I found it interesting that none of this information appeared in his MPD statement. Huckaby agreed to testify.Another person whose name appeared in the MPD report with no apparent significance was Robert Hagerty, who at the time was employed at the Lucky Electric Supply Company on Butler, just behind the Lorraine. During the afternoon of April 4 he noticed a sedan parked diagonally across from his shop just off Butler Street in such a way as to allow anyone inside a clear view of the balcony of the Lorraine Motel. There were two men dressed in civilian clothes sitting in the car, holding walkie-talkies. Hagerty didn't recognize the men as local detectives. The issue of walkie-talkies to MPD officers at that time was very limited. This was another indication that they could have been federal officers.

A second surveillance team, then, seemed to be operating on Butler, so that the Lorraine was literally sandwiched in between the two posts. We had apparently stumbled upon the first indications of a federal surveillance presence in the proximity of the Lorraine within hours of the assassination.

This surveillance presence must be viewed along with five other factors: (1) the removal of security for Dr. King, (2) the removal of Detective Redditt from his surveillance detail, (3) the transfer of firemen Newsom and Wallace, (4) the pullback of the TACT units, particularly TACT 10 and (5) the presence of Chief MacDonald in the area of the Lorraine with a walkie-talkie in hand.

Chief William Crumby had told me in 1988 that a pullback of the TACT units had occurred and that the request came in "the day before." As to who made the request, he said, as noted earlier, "It could have been Kyles." He noted, however, that the emergency vehicles were under the direct command of Inspector Sam Evans. Crumby was willing to testify to what he knew about the pullback. Inspector Sam Evans had died in 1993.

I was astounded to hear for the first time in late 1992 that Dr. King had always been provided with a small personal security force of black homicide detectives when he came to Memphis. Its very existence and function had never been made public or mentioned. The only security unit referred to by the HSCA or otherwise publicly known was the squad of white detectives formed and removed by Inspector Don Smith on the first day of Dr. King's last visit.

It was obviously important to speak with the small cadre of black homicide detectives on the force in 1968. After two interviews with officers who were not on duty on the 4th, Tom Marshall and Wendell Robinson, I met with one who was: Captain Jerry Williams, now retired from the MPD. He described how as a young homicide detective in the 1960s he was given the task by Inspector Don Smith to put together a team of four black plainclothes homicide officers to provide security for Dr. King when he came to Memphis. Such visits were infrequent; King had been in the city only a handful of times before the visits connected with the sanitation workers' strike. The four-man team would apparently remain with Dr. King wherever he went, on a twenty-four-hour detail, staying in the same hotel. Williams recalled organizing a group on two previous occasions when Dr. King was in the city. Jim Lawson subsequently told me that he remembered this group of detectives as sincere and proud of being assigned to guard Dr. King.

I told Williams that for a number of years I had been very interested in where Dr. King stayed on his various visits to Memphis. In light of the FBI-generated criticism of him prior to his decision to stay at the Lorraine on his last visit, I wanted to know whether he had, in fact, ever stayed at that motel before. Williams said that on the previous visits he remembered Dr. King staying at the Rivermont and the Admiral Benbow Inn but didn't recall him ever staying overnight at the Lorraine Motel. He said, however, that he might take a room there to receive local blacks who could visit more comfortably than in the white-owned hotels. (At that time, only a couple of motels didn't exclude blacks.) As Williams spoke, I remembered seeing a photograph taken by Ernest Withers of Dr. King during such a visit standing at the door of room 307.

"I was always troubled that I wasn't instructed to put together the security team for Dr. King's last visit," Williams said. He was certain that no one else had been given the assignment because he had discussed it with various black officers after the killing. When asked whether he ever asked Don Smith why the detail wasn't formed, he smiled and gently said no, that it wasn't something you would do in those days. Back then a black police officer couldn't even arrest a white person. The most he could do was to detain a suspect and call for a white officer to arrive.

Williams had formed the detail at Inspector Smith's request as recently as March 18, when Dr. King came to town to address a strike rally for the first time. On that visit Dr. King stayed in the top floor suite at the Holiday Inn Rivermont Hotel, and Detective Williams and his team posted a man in front of his door and stayed in nearby rooms. Williams believed that a unit was also in place on the evening of March 28, after the march broke up in violence, but he didn't recall who formed it, speculating that it was R. J. Turner, who had since died.

In his testimony before the HSCA, Inspector Smith stated that he had put together a security group that met Dr. King at the airport and followed him to the Lorraine on April 3. This detail consisted entirely of white detectives. They were Lt. George Kelly Davis, Lt. William Schultz, and Detective Ronald B. Howell, joined by Inspector J. S. Gagliano and lieutenants Hamby and Tucker at the Lorraine. Not one of them had any previous history of being assigned to Dr. King, nor would they have been regarded as suitable in terms of relating to the civil rights leader or his purposes. But since information about this previous black security detail had been concealed until now, Smith's white security force was never viewed in its proper context.

The detail was removed at Smith's own request later that same afternoon when he stated that he believed that the King party wasn't cooperating with them. (Jim Lawson and Hosea Williams maintain that there was no lack of cooperation from the King party.)

According to the HSCA report, when Inspector Smith asked for permission to withdraw the detail, chief of detectives William Huston allegedly conferred with Chief MacDonald who gave permission for the withdrawal, though MacDonald maintained that he did not recall the request, or removal. The HSCA also noted that Director Holloman maintained that he knew nothing about these decisions8 and further stated that it "... tried to determine if Dr. King was provided protection by the MPD on earlier trips to Memphis but it could not resolve the question." [9]

This wasn't surprising, since no one from the FBI or the HSCA ever questioned Jerry Williams or any member of the previous security details he pulled together: Elmo Berkley, Melvyn Burgess, Wendell Robinson, Tom Marshall, R. J. Turner, Caro Harris, Ben Whitney, and Emmett J. Winters.

Williams was certain that if his usual team had been in place it could not and would not have been removed as easily as could some other white officers. The prosecution would say it was another coincidence. I regarded the omission of black security officers on Dr. King's last visit as one of the most sinister discoveries yet.

***

I SPENT SIX HOURS WITH MORRIS DAVIS in Birmingham on November 28. As previously mentioned years earlier, I had acquired an affidavit in which Davis contended that he had become aware of a plot to kill Dr. King involving Birmingham medical doctor Gus Prosch, a Frank Liberto, Ralph Abernathy and Fred Shuttlesworth. The HSCA had summarized Davis's allegations in its report, before dismissing them. Though giving little credence to most of his allegations, I was interested to learn what he knew about any involvement of Frank Liberto.

He said that in 1967 and 1968 he frequented the Gulas Lounge in Birmingham. There he became friendly with a Dr. Gus Prosch, who some years later would be convicted for illegal gun dealing and income tax evasion. Prosch introduced him to a man named Frank Liberto.

It soon became clear to me that Davis wasn't talking about any of the three Memphis Frank Libertos we had come across, but another Frank Liberto, whom he described as being dark haired and dark complected, between thirty- five and forty years old, about six feet tall and around 190 pounds. This Liberto allegedly had businesses in both Memphis and New Orleans.

Davis had earlier in the 1960s acted as a paid informant for the Secret Service, in counterfeiting matters, and the Drug Enforcement Agency (DEA). He said he assisted the Birmingham police in their investigation of the bombing of the 16th Avenue Church in which four children died, and they fed him information on various matters which interested him, some of which he would pass on to his federal agency contacts.

Davis maintained that the DEA files showed that one Frank Liberto was part of a major international drug trafficking operation associated with the Luigi Greco family in Montreal and that his operation spread from Corpus Christi, Texas, to Memphis, New Orleans, and Los Angeles, with family contacts in Detroit and Toronto. He said that Liberto was based primarily in New Orleans and had a home on Lake Ponchartrain outside of New Orleans.

Davis said that he had gone to Memphis in 1977-78 at his own expense to investigate the King assassination as part of some informal arrangement with the HSCA. In Memphis he met a Liberto flunky he knew only as Ed. He first saw Ed coming out of Frank's [Frank Liberto's] liquor store at 327 South Main Street. Ed outlined the gunrunning and drug operations of Frank Liberto. He said that guns were smuggled into Latin America over the border near Corpus Christi, Texas, in exchange for cocaine and marijuana. Ed also said that Liberto ran a number of gambling operations in various sections of Memphis.

Ed then took Morris Davis to the Liberto business where Ezell Smith worked. He told Davis that around 7:30 p.m. on March 30 James delivered to those premises the rifle he had purchased earlier that day. It was kept there until the morning of April 4, when it was fired once and the cartridge left in the gun. Its sole purpose was to be a throwdown gun for the cover-up of the killing.

I stiffened. Once again, the same building was being raised. The photograph of that building and its handwritten note flashed in my mind. Had Davis been the source of that photocopy? Subsequently, he was to say that he was not, although there was some similarity in the handwriting. (As mentioned earlier, the building was the one in the photograph which turned out to be the same one also allegedly referred to by Ezell Smith and of course owned by a relative of produce man Frank Liberto.)

Davis said that he confirmed at the Memphis land records office that most of the buildings in the 300 to 400 block of South Main Street -- including the Merchant's Lounge, the liquor store and the Green Beetle -- were owned by Frank Liberto, although a number were in his father's name. His father, according to Davis, was also Frank Liberto (Frank H.), who lived on the Memphis-Arlington Road in a large estate purchased in 1974. Davis knew nothing more about the father. I knew that the person at this address was auto dealer Frank Liberto, who in 1992 was in his eighties. There was no way this Liberto could have been the father of the Frank Liberto who owned the liquor store and the Green Beetle, who in 1992 was dead but would have also been around eighty years old.

Ed said that a person named Jim Bo Stewart handled business for Liberto when he was away. He also confirmed that James was a patsy/decoy and that they meant to kill him after the job was completed. Ed claimed at one point to have been sent inside the prison by Frank Liberto on an arranged drug charge to kill James in 1969.

Davis then went on to say that some details that HSCA investigator Al Hack gave him began to corroborate what he himself had observed in March 1968 as well as what he had learned from Ed and his own DEA sources. Hack told him that he had obtained two phone numbers called by James before he left Puerto Vallarta for Los Angeles, which numbers appeared to be related to the Liberto family.

Davis said that after taking in all of his information, the HSCA buried his story and canceled his testimony on the day before it was scheduled.

There was no way that we could use any of Morris's information without obtaining specific corroboration. Even if the judge would have allowed his testimony, it would have been irresponsible to put this man on the stand. Davis understood and offered his full assistance in seeking corroboration. He suggested that I speak with Robert Long and Oscar Kent, each of whom knew about some aspect of the story. Davis also agreed to let me have his entire set of files on the case.

I couldn't locate Robert Long, and though Oscar Kent was still in the area I wasn't able to catch up with him at this time. I set about attempting to see what could be corroborated.

As for the gambling dens Davis described, S. O. Blackburn, a former MPD officer who had been assigned to investigate illegal gambling operations, later confirmed that there was a good deal of it going on during the time. At least two of the Frank Libertos (produce man and liquor man) and another member of the Liberto family were involved, and one of the gambling dens frequented was the Check Off (formerly the Tremont Cafe) which had been owned at the time by Loyd Jowers.

Ken Herman said that former Birmingham detective Rich Gianetti remembered Davis as a person who sold information and whose accounts were truthful. Gianetti also remembered a Frank Liberto who said he was from New Orleans and who visited the Gulas Lounge and spent money liberally. He said he was a good dresser and his description roughly matched the one Davis gave. When I later spoke with Gianetti, however, he said he only vaguely remembered the name of Frank Liberto.

Davis had maintained that HSCA counsel and staff had visited him at various times and he had provided the names and dates of these visits. Since these men were federal employees, there would be a public record of their expense requests and payments. An analysis of the General Services Administration (GSA) disbursement records for special and select committees obtained by D. C. investigator Kevin Walsh basically confirmed Davis's recollections and notes. It was obvious that the HSCA had devoted a considerable amount of time to Morris Davis. The principal HSCA investigator assigned to Davis was Al Hack. Subsequently I spoke to Hack, who admitted that Davis had appeared to have credibility as an informant for other federal agencies and that he did trade in information but try as they might, they could not confirm Davis's allegations. Hack's partner in the investigation was an Atlanta policeman named Rosie Walker who had since died. I suspected his files on the case might help us and asked our Atlanta private investigator to try to obtain them.

Aside from the Liberto allegations, some of which would be corroborated, Davis's statements about Abernathy, Shuttlesworth, and a range of other people and events, were, for one reason or another, not believable. Whether this was the result of honest mistakes, deliberate fabrication or official disinformation was not clear. Davis stood by his story and said that he recorded a number of his conversations with HSCA staff which would substantiate his claims. I could not listen to them because the equipment required had long ago ceased to be manufactured, though Davis's lawyer undertook to try to find a compatible machine.

***

THE EVIDENCE WE HAD UNEARTHED up until now tied together and strengthened evidence discovered earlier. Some startling contradictions to the official case had developed. There could no longer be any doubt that the chief prosecution witness had been drunk and unable to observe anything. Also it was clear that Chastain's earlier information about there being a change of Dr. King's room at the Lorraine was correct. Somehow he had been mysteriously moved from a secluded, ground-level courtyard room to a highly exposed balcony room. Lorraine employee Olivia Hayes recalled this and then Leon Cohen confirmed it, re- counting his conversation at the time with Walter Bailey, the owner of the Lorraine.

As a result of the observations of Solomon Jones, James Orange, and Earl Caldwell, it now appeared conclusive that the fatal shot was fired from the brush area and not from the bathroom. We had seen evidence of the fresh footprints found in that brush area, which as Kay Black and James Orange alleged fourteen years earlier, was cut down and cleared early the morning after the killing, possibly along with an inconveniently placed tree branch.

A number of suspicious events were confirmed. The only two black firemen had been taken off their posts the night before the killing. These reassignments -- considered along with the removal of black detective Ed Redditt from his surveillance post and the failure of the MPD to form the usual security squad of black detectives for Dr. King -- were ominous. The emergency TACT units were also pulled back, with TACT 10 being moved from the Lorraine to the fire station. Finally, on Butler and Huling streets bordering the Lorraine) there were apparently surveillance details of some federal agency that afternoon.

In addition, for the first time evidence had been uncovered that the CB hoax broadcast, which drew police attention to the northeastern side of the city, had been transmitted from downtown near the scene of the killing.

Former FBI agent Arthur Murtagh personally confirmed a range of harassment and surveillance activity by the bureau against Dr. King, and MPD special services/intelligence bureau officer Jim Smith confirmed that Dr. King's usual suite at the Rivermont was under electronic surveillance by federal agents.

There were increasing indications that members of the Liberto family at least in Memphis and New Orleans, were implicated in the killing. For example, we learned that a rifle connected with the killing -- perhaps the murder weapon -- appeared to have been stored in the premises of a Liberto business only a few blocks from the Lorraine.

Jim's Grill owner Loyd Jowers, whose behavior had always seemed curious, seemed increasingly likely to have played a role. Not only was his involvement rumored locally, but a bailbondsman quoted one of Jowers's waitresses as pointing the finger at her boss. Taxi driver McCraw had earlier claimed that Jowers showed him a rifle he had under the counter in the grill that he contended was the murder weapon.