by Robert Parry

October 28, 2014

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

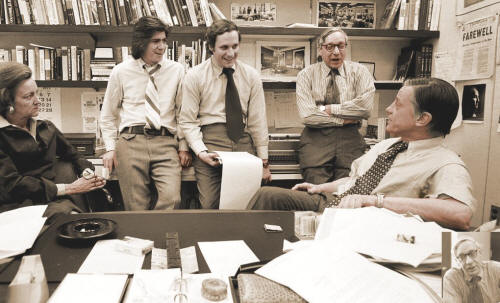

The Washington Post’s Watergate team, including from left to right, publisher Katharine Graham, Carl Bernstein, Bob Woodward, Howard Simons, and executive editor Ben Bradlee.

Following the death last week of legendary Washington Post executive editor Ben Bradlee at age 93, there have been many warm remembrances of his tough-guy style as he sought “holy shit stories,” journalism that was worthy of the old-fashioned demand, “stop the presses.”

Many of the fond recollections surely are selective, but there was some truth to Bradlee’s “front page” approach to inspiring a staff to push the envelope in pursuit of difficult stories at least during the Watergate scandal when he backed Bob Woodward and Carl Bernstein in the face of White House hostility. How different that was from Bradlee’s later years and the work of his successors at the Washington Post!

Coincidentally, upon hearing of Bradlee’s death on Oct. 21, I was reminded of this sad devolution of the U.S. news media from its Watergate/Pentagon Papers heyday of the 1970s to the “On Bended Knee” obsequiousness in covering Ronald Reagan just a decade later, a transformation that paved the way for the media’s servile groveling at the feet of George W. Bush last decade.

On the same day as Bradlee’s passing, I received an e-mail from a fellow journalist informing me that Bradlee’s longtime managing editor and later his successor as executive editor, Leonard Downie, was sending around a Washington Post article attacking the new movie, “Kill the Messenger.”

That article by Jeff Leen, the Post’s assistant managing editor for investigations, trashed the late journalist Gary Webb, whose career and life were destroyed because he dared revive one of the ugliest scandals of the Reagan era, the U.S. government’s tolerance of cocaine trafficking by Reagan’s beloved Nicaraguan Contra rebels.

“Kill the Messenger” offers a sympathetic portrayal of Webb’s ordeal and is critical of the major newspapers, including the Washington Post, for denouncing Webb in 1996 rather than taking the opportunity to revisit a major national security scandal that the Post, the New York Times and other major newspapers missed or downplayed in the mid-1980s after it was first reported by Brian Barger and me for the Associated Press.

Downie, who became the Post’s managing editor in 1984 and followed Bradlee as executive editor in 1991 and is now a journalism professor at Arizona State University passed Leen’s anti-Webb story around to other faculty members with a cover note, which read:

“Subject line: Gary Webb was no hero, say[s] WP investigations editor Jeff Leen

“I was at The Washington Post at the time that it investigated Gary Webb’s stories, and Jeff Leen is exactly right. However, he is too kind to a movie that presents a lie as fact.”

Since I knew Downie slightly during my years at the Associated Press he had once called me about my June 1985 article identifying National Security Council aide Oliver North as a key figure in the White House’s secret Contra-support operation I sent him an e-mail on Oct. 22 to express my dismay at his “harsh comment” and “to make sure that those are your words and that they accurately reflect your opinion.”

I asked, “Could you elaborate on exactly what you believe to be a lie?” I also noted that “As the movie was hitting the theaters, I put together an article about what the U.S. government’s files now reveal about this problem” and sent Downie a link to that story. I have heard nothing back. [For more on my assessment of Leen’s hit piece, see Consortiumnews.com’s “WPost’s Slimy Assault on Gary Webb.”]

Why Attack Webb?

One could assume that Leen and Downie are just MSM hacks who are covering their tracks, since they both missed the Contra-cocaine scandal as it was unfolding under their noses in the 1980s.

Leen was the Miami Herald’s specialist on drug trafficking and the Medellin cartel but somehow he couldn’t figure out that much of the Contra cocaine was arriving in Miami and the Medellin cartel was donating millions of dollars to the Contras. In 1991, during the drug-trafficking trial of Panama’s Manuel Noriega, Medellin cartel kingpin Carlos Lehder even testified, as a U.S. government witness, that he had chipped in $10 million to the Contras.

Downie was the Washington Post’s managing editor, responsible for keeping an eye on the Reagan administration’s secretive foreign policy but was regularly behind the curve on the biggest scandals of the 1980s: Ollie North’s operation, the Contra-cocaine scandal and the Iran-Contra Affair. After that litany of failures, he was promoted to be the Post’s executive editor, one of the top jobs in American journalism, where he was positioned to oversee the takedown of Gary Webb in 1996.

Though Downie’s note to other Arizona State University professors called the Contra-cocaine story or “Kill the Messenger” or both a “lie,” the Huffington Post’s Ryan Grim recounted recently in an article about the big media’s assault on Webb that “The Post’s top editor at the time, Leonard Downie, told me that he doesn’t remember the incident well enough to comment on it.”

But there’s more here than just a couple of news executives who find it easier to pile on a journalist no longer around to defend himself than to admit their own professional failures. What Leen and Downie represent is an institutional failure of American journalism to protect the American people, choosing instead to protect the American power structure.

Remember that in the mid-1980s when Barger and I exposed the Contra-cocaine scandal, the smuggling was happening in real time. It wasn’t history. The various Contra pipelines were bringing cocaine into American cities where some was getting processed into crack. If action had been taken then, at least some of those shipments could have been stopped and some of the Contra traffickers prosecuted.

Yet, instead of the major news media joining in exposing these ongoing crimes, the New York Times and Washington Post chose to look the other way. In Leen’s article, he justifies this behavior under a supposed journalistic principle that “an extraordinary claim requires extraordinary proof.” But any such standard must also be weighed against the threat to the American people and others from withholding a story.

If Leen’s principle means in reality that no level of proof would be sufficient to report that the Reagan administration was protecting Contra-cocaine traffickers, then the U.S. media was acquiescing to criminal activity that wreaked havoc on American cities, destroyed countless lives and overflowed U.S. prisons with low-level drug dealers while powerful people with political connections went untouched.

That assessment is essentially shared by Doug Farah, who was a Washington Post correspondent in Central America at the time of Webb’s “Dark Alliance” series in 1996. After reading Webb’s series in the San Jose Mercury News, Farah was eager to advance the Contra-cocaine story but encountered unrealistic demands for proof from his editors.

Farah told Ryan Grim: “If you’re talking about our intelligence community tolerating — if not promoting — drugs to pay for black ops, it’s rather an uncomfortable thing to do when you’re an establishment paper like the Post. … If you were going to be directly rubbing up against the government, they wanted it more solid than it could probably ever be done.”

In other words, “extraordinary proof” meant you’d never write a story on this touchy topic because no proof is 100 percent perfect, apparently not even when the CIA’s inspector general confesses, as he did in 1998, that much of what Webb, Barger and I had reported was true and that there was much, much more. [See Consortiumnews.com’s “The Sordid Contra Cocaine Scandal.”]

What Happened to the Press?

How this transformation of Washington journalism occurred from the more aggressive press corps of the 1970s into the patsy press corps of the 1980s and beyond is an important lost chapter of modern American history.

Much of this change emerged from the political wreckage that followed the Vietnam War, the Pentagon Papers, the Watergate scandal and the exposure of CIA abuses in the 1970s. The American power structure, particularly the Right, struck back, labeling the U.S. news media as “liberal” and questioning the patriotism of individual journalists and editors.

But it didn’t require much arm-twisting to get the mainstream news media to bend into line and fall on its knees. Many of the news executives that I worked under shared the view of the power structure that the Vietnam protests were disloyal, that the U.S. government needed to hit back against humiliations like the Iran-hostage crisis, and that the rebellious public needed to be brought back into line behind more traditional values.

At the Associated Press, its most senior executive, general manager Keith Fuller, gave a 1982 speech in Worcester, Massachusetts, hailing Reagan’s election in 1980 as a worthy repudiation of the excesses of the 1960s and a necessary corrective to the nation’s lost prestige of the 1970s. Fuller cited Reagan’s Inauguration and the simultaneous release of the 52 U.S. hostages in Iran on Jan. 20, 1981, as a national turning point in which Reagan had revived the American spirit.

“As we look back on the turbulent Sixties, we shudder with the memory of a time that seemed to tear at the very sinews of this country,” Fuller said, adding that Reagan’s election represented a nation “crying, ‘Enough.’

“We don’t believe that the union of Adam and Bruce is really the same as Adam and Eve in the eyes of Creation. We don’t believe that people should cash welfare checks and spend them on booze and narcotics. We don’t really believe that a simple prayer or a pledge of allegiance is against the national interest in the classroom.

“We’re sick of your social engineering. We’re fed up with your tolerance of crime, drugs and pornography. But most of all, we’re sick of your self-perpetuating, burdening bureaucracy weighing ever more heavily on our backs.”

Fuller’s sentiments were not uncommon in the executive suites of major news organizations, where Reagan’s reassertion of an aggressive U.S. foreign policy was especially welcomed. At the New York Times, executive editor Abe Rosenthal, an early neocon, vowed to steer his newspaper back “to the center,” by which he meant to the right.

There was also a social dimension to this journalistic retreat. For instance, the Washington Post’s longtime publisher Katharine Graham found the stresses of high-stakes adversarial journalism unpleasant. Plus, it was one thing to take on the socially inept Richard Nixon; it was quite another to challenge the socially adroit Ronald and Nancy Reagan, whom Mrs. Graham personally liked.

The Graham family embraced neoconservatism, too, favoring aggressive policies against Moscow and unquestioned support for Israel. Soon, the Washington Post and Newsweek editors were reflecting those family prejudices.

I encountered that reality when I moved from AP to Newsweek in 1987 and found executive editor Maynard Parker, in particular, hostile to journalism that put Reagan’s Cold War policies in a negative light. I had been involved in breaking much of the Iran-Contra scandal at the AP, but I was told at Newsweek that “we don’t want another Watergate.” The fear apparently was that the political stresses from another constitutional crisis around a Republican president might shatter the nation’s political cohesion.

The same was true of the Contra-cocaine story, which I was prevented from pursuing at Newsweek. Indeed, when Sen. John Kerry advanced the Contra-cocaine story with a Senate report issued in April 1989, Newsweek was uninterested and the Washington Post buried the story deep inside the paper. Later, Newsweek dismissed Kerry as a “randy conspiracy buff.” [For details, see Robert Parry’s Lost History.]

Fitting a Pattern

In other words, the vicious destruction of Gary Webb following his revival of the Contra-cocaine scandal in 1996 when he examined the impact of one Contra-cocaine pipeline into the crack trade in Los Angeles was not out of the ordinary. It was part of the pattern of subservience to the national security apparatus, especially under Republicans and right-wingers but extending to Democratic hardliners, too.

This pattern of bias continued into last decade, even when the issue was whether the votes of Americans should be counted. After the 2000 election, when George W. Bush got five Republicans on the U.S. Supreme Court to halt the counting of votes in the key state of Florida, major news executives were more concerned about protecting the fragile “legitimacy” of Bush’s tainted victory than ensuring that the actual winner of the U.S. presidential election became president.

After the Supreme Court’s Republican majority made sure that Florida’s electoral votes and thus the presidency would go to Bush, some news executives, including the New York Times’ executive editor Howell Raines, bristled at proposals to do a media count of the disputed ballots, according to a New York Times executive who was present for these discussions.

The idea of this media count was to determine who the voters of Florida actually favored for president, but Raines only relented to the project if the results did not indicate that Bush should have lost, a concern that escalated after the 9/11 attacks, according to the account from the Times executive.

Raines’s concern became real when the news organizations completed their unofficial count of Florida’s disputed ballots in November 2001 and it turned out that Al Gore would have carried Florida if all legally cast votes were counted regardless of what standards were applied to the famous chads dimpled, hanging or punched-through.

Gore’s victory would have been assured by the so-called “over-votes” in which a voter both punched through a candidate’s name and wrote it in. Under Florida law, such “over-votes” are legal and they broke heavily in Gore’s favor. [See Consortiumnews.com’s “So Bush Did Steal the White House” or our book, Neck Deep.]

In other words, the wrong candidate had been awarded the presidency. However, this startling fact became an inconvenient truth that the mainstream U.S. news media decided to obscure. So, the major newspapers and TV networks hid their own scoop when the results were published on Nov. 12, 2001.

Instead of stating clearly that Florida’s legally cast votes favored Gore and that the wrong man was in the White House the mainstream media bent over backwards to concoct hypothetical situations in which Bush might still have won the presidency, such as if the recount were limited to only a few counties or if the legal “over-votes” were excluded.

The reality of Gore’s rightful victory was buried deep in the stories or relegated to data charts that accompanied the articles. Any casual reader would have come away from reading the New York Times or the Washington Post with the conclusion that Bush really had won Florida and thus was the legitimate president after all.

The Post’s headline read, “Florida Recounts Would Have Favored Bush.” The Times ran the headline: “Study of Disputed Florida Ballots Finds Justices Did Not Cast the Deciding Vote.” Some columnists, such as the Post’s media analyst Howard Kurtz, even launched preemptive strikes against anyone who would read the fine print and spot the hidden “lede” of Gore’s victory. Kurtz labeled such people “conspiracy theorists.” [Washington Post, Nov. 12, 2001]

An Irate Reporter

After reading these slanted “Bush Won” stories, I wrote an article for Consortiumnews.com noting that the obvious “lede” should have been that the recount revealed that Gore had won. I suggested that the news judgments of senior editors might have been influenced by a desire to appear patriotic only two months after 9/11. [See Consortiumnews.com’s “Gore’s Victory.”]

My article had been up for only a couple of hours when I received an irate phone call from New York Times media writer Felicity Barringer, who accused me of impugning the journalistic integrity of executive editor Raines.

Though Raines and other executives may have thought that what they were doing was “good for the country,” they actually were betraying their most fundamental duty to the American people to give them the facts as fully and accurately as possible. By falsely portraying Bush as the real winner in Florida and thus in the Electoral College, these news executives infused Bush with false legitimacy that he then abused in leading the country to war in Iraq in 2003.

Again, in that run-up to the Iraq invasion, the major news media performed more as compliant propagandists than independent journalists, embracing Bush’s false WMD claims and joining in the jingoism that celebrated “the troops” and the initial American conquest of Iraq.

Despite the media’s embarrassment that later surrounded the bogus WMD stories and the disastrous Iraq War, mainstream news executives faced no accountability. Howell Raines lost his job in 2003 not because of his unethical handling of the Florida recount or the false Iraq War reporting, but because he trusted reporter Jayson Blair who fabricated sources in the Beltway Sniper Case.

How distorted the Times’ judgment had become was underscored by the fact that Raines’s successor, Bill Keller, had written a major article “The I-Can’t-Believe-I’m-a-Hawk Club” hailing “liberals” who joined him in supporting the Iraq invasion. In other words, you got fired if you trusted a dishonest reporter but got promoted if you trusted a dishonest president.

Similarly, at the Washington Post, editorial-page editor Fred Hiatt, who reported again and again that Iraq was hiding stockpiles of WMD as “flat-fact,” didn’t face the kind of journalistic disgrace that was meted out to Gary Webb. Instead, Hiatt is still holding down the same prestigious job, writing the same kind of imbalanced neocon editorials that guided the American people into the Iraq disaster, except now Hiatt is pointing the way to deeper confrontations in Syria, Iran, Ukraine and Russia.

So, perhaps it should come as no surprise that this thoroughly corrupted Washington press corps would lash out again at Gary Webb as his reputation has the belated chance for a posthumous rehabilitation.

But how far the vaunted Washington press corps has sunk is illustrated by the fact that it has been left to a Hollywood movie of all things to set the record straight.