by C. Lawrence Meador and Vinton G. Cerf

Studies in Intelligence Vol. 57, No. 4

(Extracts, December 2013)

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

The expanded use of [tablet-like, visualization, and other new] technologies has dramatic implications for those who create, deliver, and use the PDB, with exciting possibilities for the establishment of even more intimate and effective IC engagement with top-level leaders.”

Introduction

A primary function of the Intelligence Community (IC) is to support the president, the National Security Council, and other top government leaders. The most well-known example of this support is the President’s Daily Briefing (PDB). The PDB—as reflected in actual printed products and the person-to-person interactions between PDB recipients and intelligence briefers—has evolved over the decades into an exquisitely choreographed effort. The recent limited and experimental use for this purpose of an electronic tablet and the potential to leverage advances in visualization and other powerful hardware and software applications presents a potential new chapter for the PDB. [1] The expanded use of these technologies has dramatic implications for those who create, deliver, and use the PDB, with exciting possibilities for the establishment of even more intimate and effective IC engagement with top-level leaders.

A small panel of interested professionals that we were part of explored the implications of the use of new technologies in order to inform discussion of adaptations to the PDB, both as a product and a process. Of particular interest to those of us on the panel were

•possible changes in the interaction of information providers and recipients;

•changes in the kinds of information provided and its display using the new technologies;

•specialized software capabilities to yield the highest levels of satisfaction; and

•complementarities with other media of information exchange and interaction.

Additionally, the panel was interested in other forms of visual display or information transmission and collaboration that are on the horizon, and how all these changes may affect the IC’s operating model.

We took a four-pronged approach to our task:

•We observed the current PDB process, to include how the tablet is used.

•We considered the insights of practitioners and the literature on decision support and executive information systems.

•We interviewed or received briefings from more than 90 individuals in government, private industry and in nonprofit and academic sectors.

•A panel of senior external experts also advised us and reviewed our findings and recommendations.

While we make several observations about the current PDB process, the focus of this article is on a future environment in which tablets and other platforms are the principal mechanisms for presenting and visualizing intelligence to senior leaders. And while this article mainly treats the PDB, the experience with the PDB promises to set standards and conventions for IC support to other senior leaders as well.

We will not advocate here the targeting of the PDB to a larger audience—we think it should continue to be disseminated as the president desires and that briefers continue personally to deliver the PDB to presidentially approved recipients. We will suggest that using currently available technology to improve dissemination of intelligence information to other US leaders (especially in the IC) is an idea worth discussing.

Here we will outline how the PDB, when considered as a decision-support and executive-information system, can be tailored to the relatively unstructured problem environment that top government leaders often face and expect the IC to help address.

We concluded that the PDB should evolve around five design principles. It should be

•focused squarely on policymakers’ problems;

•adaptable to a variety of needs and styles;

•capable of providing increasingly “curatorial” versus strictly editorial functions;

•able to embrace a risk-management approach to security concerns; and

•extensible to a leader’s broader information and communications ecosystem.

The visualization, data-manipulation, and data-exploitation capabilities inherent in a tablet computer and similar platforms provide opportunities to reshape the structure and dynamics of top-level support.

We recommend the inclusion of several capabilities in the following areas:

•architecture

•annotation and feedback mechanisms

•access

•search

•security

•the PDB as a full-featured information support device.

Advancements in these areas are technically feasible and can be delivered with effective security. Used together, improvements could form the basis for dramatic shifts in current IC processes. They could

•support greater access to amplifying sources, visuals, and multi-media;

•provide continuously updated information and analysis—accessible 24/7—instead of a single 15–30 minute briefing session;

•make possible connectivity to other communications capabilities, e.g., e-mail; and

•simplify the PDB recipient’s day.

The largest challenges to implementing such shifts will be making adjustments to the PDB process and the culture that now governs the relationship between intelligence officials and senior leaders. In making these changes, the IC has the potential to move from a model of providing primarily finished analytic products—in relatively staged, controlled interactions—to a new model of engaging in dynamic relationships between policymaker and intelligence officer, a model in which sources are referred to, key insights continuously updated, and feedback provided more comprehensively. Such a transformation in the PDB would also be likely to require alteration of many processes across the Intelligence Community as a whole.

The Evolving PDB

The provision of current intelligence to presidents has a deep tradition, dating to 1946, but it has never been a static effort. The appearance, content, and delivery approaches have evolved to reflect the attitudes of presidents toward intelligence; their varied cognitive styles and preferred means of receiving information—through a national security advisor, a mid-ranking or senior intelligence officer, or from the head of the Intelligence Community; and advances in technological capabilities.

The daily face-to-face briefings of presidents, which began in the mid-1970s, revolutionized the PDB, even if not all presidents since received such briefings. In that time, the PDB has been seen as a means for the IC and its leaders to earn the confidence of presidents and their administrations and to offer a mechanism for presidents to provide feedback and tasking. As a result, the experience that the PDB creates is of central importance to the president and the IC. [2]

The president has always had the last word on how his version of the PDB is crafted in content and format and the way it is delivered. However, at least in recent years, designated principals and other presidentially approved recipients of the PDB have in many cases put their own fingerprints on content, format and delivery, thus tailoring the PDB to their own unique needs.

Enter Tablet Computing

Advances in information technology during recent years are on the cusp of radically altering the PDB both as a published product and as a personally delivered briefing. High-powered computing, advanced encryption and security, broadband, wireless and global Internet connectivity, along with the proliferation of fixed and mobile platforms, are creating new opportunities for delivering intelligence support as well as receiving feedback and tasking from recipients. The recent limited and experimental introduction of the tablet computer to convey the PDB reflects this shift.

Like all technological innovations, the tablet offers new capabilities, but it also has the potential to affect the relationships and experiences of the individuals and organizations involved in its use. When combined with other information and communications technologies, the tablet foretells a different user experience, marked by, among other things, dramatically increased demands for all sorts of information by “power users,” greater expectations for intelligence responsiveness, and the desire to reach the frontline intelligence officer directly—in some cases without the filter of a briefer or PDB production team.

The prevalence of a connected-information environment in professional and personal lives, coupled with changes the IC is making in product development, display, and access, is producing an expectation of greater insights, more compelling visualizations, and almost instant updates on the most important and critical matters. IT devices are verging on being “tethered minds” that provide continuous analytical support. A more radical future vision is thus eminently plausible: a shift in the PDB from a once-a-day production-and-brief-engagement model, to continuous, near real-time, virtual support, punctuated by periodic physical interactions, some regularly scheduled and some when called for by urgent situations.

The use of tablets also implies important shifts in process, style, and influence in the relationship between PDB recipients and intelligence officers who provide the PDB. For example, a tablet could offer more direct access to detailed information, a shift that could affect a briefer’s role as intermediary. Or, a tablet device could give intelligence officers greater access and influence because of the ubiquity of these devices in the lives of today’s and future leaders.

Tablet devices thus have the potential to create new levels of intimacy between leader and intelligence officer. In addition, the production cycle for the PDB might assume a higher tempo (and thus consume greater resources or require a fundamentally different process), with greater emphasis on providing incremental insights.

In our judgment, these challenges have kept leaders and intelligence officers who would provide the new technology from universally and immediately embracing it. “Early adopters” see wide adoption of the tablet as inevitable because of the opportunities it will afford and they will tolerate (or embrace) shifts in interaction styles as part and parcel of innovation.

A “wait-and-see” group finds the tablet appealing and potentially valuable, but its members are frustrated by limitations in the functionality of current tablets, anticipate security concerns that will limit the tablet’s effectiveness, and generally embrace incrementalism to avoid major changes in current relationships.

“Late adopters” believe the tablet may not displace the intangible dynamic of the combined book and oral briefing and find the more arm’s-length relationship useful for maintaining institutional independence. But the introduction of new technological capabilities does not have to be forced on any reluctant principals. It should be voluntary and if it is done well, the early adopters will serve as models for emulation by others. But principals who want to continue with the hard copy version of the PDB should not be prevented from having it.

The pace and form by which the tablet is incorporated into the president’s daily intelligence effort will reflect how the concerns of these three groups are addressed throughout the PDB life cycle. This paper principally deals with the PDB as a presidential document and briefing interaction. But the experience with the PDB promises to set standards and conventions for how the IC supports other policymaker sets and its own leaders.

PDB as a Decision-Support and Executive-Information System

During our inquiry, we came to think of the PDB process in terms of a decision-support and executive-information system. Such systems first emerged to assist top corporate executives carry out strategic and tactical planning, acquire competitive and market intelligence, and conduct operations and finance functions. Thinking about such systems has since come to the medical, civilian government, military, and—increasingly—intelligence professions.

These applications are sometimes referred to as “executive support systems” or “dashboards.” Their development and increased sophistication have been propelled by ever-increasing processor performance, memory capacity, high-resolution visualization, and wireless connectivity. (See table for a list of representative entities in corporate, medical, and government domains.)

Successful decision-support and executive-information systems are tailored to their problem environments; the cognitive, communications, leadership, and interaction styles of users; and the larger information ecosystem in which they operate. Problem environments facing senior leaders can be generally placed into a range of structured and unstructured environments. Structured environments typically are well known and well understood, with clear methodologies (and in some cases algorithms) for assessing data (or the absence of it). These environments generally invoke preprogrammed decision processes.

Representative Users of Decision-Support Systems

Business

Abbott Laboratories, American Airlines, American Express, Cigna, Citibank, DuPont, IBM, Johnson Controls, Motorola, Nationwide Insurance Company, Pfizer, Sprint Nextel, Transamerica, United Airlines, Verizon, and Walmart.

Medical institutions

Aetna Health Care, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Brigham & Women’s Hospital, Geisinger Health System, Harvard Medical School, Kaiser Permanente, Mayo Clinic, MIT Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Lab, Stanford Medical School, United Healthcare, and Vanderbilt University Medical Center.

US government

Department of Agriculture’s National Institute of Food & Agriculture, Department of Defense (Defense Knowledge Online), Department of Health and Human Services, Department of Homeland Security, Department of Housing and Urban Development, Department of State, Census Bureau, Federal Aviation Administration, NASA, National Library of Medicine, National Science Foundation, Small Business Administration, Smithsonian Institution, USAID, US General Services Administration, US Navy, US Army (Army Knowledge Online), US Air Force, US Marines, and US Coast Guard. There are many more. [5]

In contrast, unstructured environments have highly variable parameters: data can be ambiguous, misleading, or even deceptive and come in many forms and dimensions. For such environments, decision processes are nonprogrammed, i.e., subject to interpretation, debate, and ultimately individual judgment. It is in addressing these unstructured problems that senior leaders most often look to intelligence for help.

In unstructured problem environments, decisionmakers tend to generalize problems into more broadly understood categories and they seek more data. An effective decision-support and executive-information system provides an alternative, first by helping leaders identify narrower sub-problems and then by organizing, sorting, culling, utilizing, and making sense of existing data more effectively. In short, these systems provide context for officials to face complex policy and operational choices with greater understanding and confidence. From this perspective, the tablet and other technologies provide opportunities to use the PDB to provide better and more relevant information to senior officials.

In today’s corporate world, decision-support systems reflect a few common principles:

•Sharing of corporate knowledge and data with and among other senior leaders within the enterprise is a given.

•Good decision-support systems will be constructed so that they can easily deliver information displays constructed to the specfic needs of an organization’s diverse senior leaders.

•Corporate systems acknowledging the variety of cognitive and communications styles within their leadership teams tailor their system to individuals as much as possible.

•The best decision-support and executive-information systems reflect communication and feedback within their communities.

Future PDB Design Principles

The unique characteristics of the PDB as a decision-support and executive-information system should be reflected in a number of implicit and explicit White House user requirements:

•The tablet should be problem-focused, guiding leaders toward issues and questions they can address by acquiring context and a clearer understanding of implications (the “so-whats”). Flooding PDB users with analyses of complex and inexplicable (or incomprehensible) phenomena will distract them and overwhelm their decisionmaking capacity.

•It must be adaptive and tailored to differing substantive needs and personal styles of its recipients. This adaptability includes choices in preferred platform (the tablet, or perhaps something else), periodicity of updates, affinity for certain visualization methods, and forms of interaction.

•The model should expand from an editorial function—in which intelligence officers determine which insights are most salient—to a more curatorial function—whereby recipients enter a structured interaction to generate insight and knowledge.

•The system should leverage all available data and information—continuously updated in near real-time, across security levels—assembled into usable composites through active engagement with PDB recipients.

•The system should rest on a risk-management framework to address legitimate security concerns. Rigorous identity and access-management protocols will be needed to ensure proper dissemination of intelligence.

•The support system must be extensible to multiple functions. If the system provides only for briefer-principal interactions, recipients may well lose faith (or interest) in it. We should avoid a scenario in which senior leaders are driven to carry multiple tablets.

•The PDB tablet should support ancillary communication functions. It should enable feedback and tasking back to the IC and connectivity to e-mail. It could—potentially, even should—be a platform through which other information feeds from intelligence leaders, commanding generals, diplomats, and others are delivered. The tablet could even feature an “alert” function so that critical intelligence could be rapidly disseminated when appropriate. Cloud computing concepts may provide some of this indispensable flexibility in an exceptionally high security environment.

Implications of Current and Evolving Technology Developments

IT advances offer profound opportunities to fuse, visualize, animate, and interact with information and data. Such methods were once possible only through high-end workstations after significant effort and time and technical assistance. Now, they are readily available by simply importing commercially available technology; applying a few basic Cloud-computing concepts to efficiently and securely deploy substantial computing power, large memory, and significant storage; and adopting certain World Wide Web protocols and mechanisms (e.g., HTML5, data tagging, CSS formatting language, JavaScript). The result will be superior intelligence that has greater impact and breeds more robust engagement.

At least three (not necessarily mutually exclusive) categories of visualization hold particular value for the IC to help show the existence and meaning of relationships, correlate disparate information to shed insight, and provide deeper context by referencing time and space.

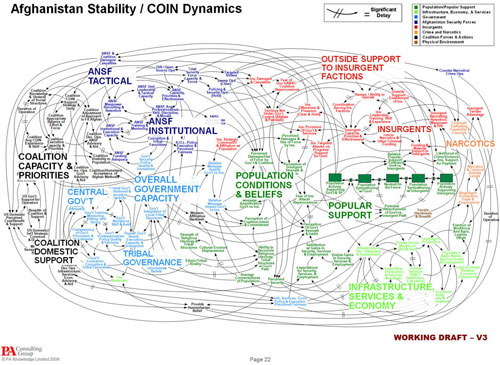

The first includes charts and graphics, which show relationships among complex data and statistics. Examples include annotated trend or event lines (the classic being Charles Joseph Minard’s rendering of losses suffered by Napoleon’s army in the Russian campaign of 1812), “bubble” or “spider” charts, and social network analyses.

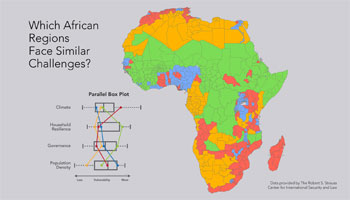

The second category includes tools that augment reality by layering many types of relevant information including data and unstructured text or graphics onto an organizing reference plane such as a map or a globe. Such tools enable the fusion of items such as imagery, video, sound tracks, statistics, charts, and map representations in a single view. Many use electronic maps or other geospatial representations to display geoindexed data on a singular spatio-temporal plane to highlight geographic coincidence of people, objects, and events and desired layers can be turned on or off as needed.

The third category is animation, which rolls across datasets to show change with graphic precision. These tools are particularly useful for yielding insights on time-series data (weather, people movements, etc.), where changes in quantity or location can be tracked and analyzed (GapMinder’s application is one example).

Software applications that employ these visualization techniques have proliferated. Social media, such as Facebook and LinkedIn, provide methods to gauge roles and strengths in relationships within people’s networks. Data and economics firms, such as Bloomberg and Hoover’s, use elaborate data displays to inform investment, business, and trading opportunities. The security, emergency management, and public health sectors use mobile applications to help identify, track, and respond to incidents of public hazard. The transportation sector monitors the movement of a significant amount of cargo and people to ensure safe and efficient passage over land and sea and through the air. Marketing firms and major retailers use social networking applications to identify customer attitudes and anticipate (or influence) future trends. The IC is using similar applications, and many would be powerful on a PDB tablet.

The maps above are taken from an integrated geospatial platform (ArcGIS) that allows user to interact with maps and investigate the underlying analytic methods and supporting data. They also permit the display of data in different time periods. In these ways, a map can serve as a powerful foundation for analysis and decisionmaking. The map of Africa (top) communicates the results of statistical clustering analysis to identify African political entities with similar vulnerability characteristics. This Web map illustrates Internet users as a share of country populations in 2001. Map symbols are dynamically derived from open-source tabular data served by the World Bank, illustrating the use of federated Web services. Users can also interrogate underlying data and retrieve thousands of other datasets. (Used with permission.)

Innovations in interactive user interfaces have greatly enhanced the impact of these visualization techniques and software applications, permitting far more direct and intimate interaction with users. These interfaces take advantage of Cloud technologies to reveal novel insights about large sets of current and historical data. For example, GapMinder software illustrates and animates up to five pieces of multidimensional, time-series information simultaneously. Tools such as Google Maps and Google Earth collate independent sources of geographically indexed information to create strong context-building environments. Interactive zoom and pan interfaces expose different levels of detail to provide the context and orientation that different users may require. Other interfaces mine and illustrate dynamics of social networks to expose otherwise unappreciated facets of relationships among key actors.

Palantir offers a suite of software applications for integrating, visualizing and analyzing many kinds of data, including structured, unstructured, relational, temporal and geospatial, in a collaborative environment. It has shown value in disparate domains, from intelligence to defense to law enforcement to financial services. TouchTable has developed a hardware and software platform for collaboration in small group environments that allows users to seamlessly share on-screen visualizations and interactions over a distributed network in a common workspace. It structures discussion geospatially and can be deployed to remote locations, including forward operating bases, command centers, and mobile field units.

The tablet is not the only device to exploit these capabilities, but for the next few years, its mobility, size, and wireless capabilities will offer more unique attributes for PDB recipients. Tablets are likely to retain value in at least two areas. One is in providing a first-order review of graphically intensive materials, leaving subsequent, more detailed review to experts using more powerful computing platforms. A second area is in readily establishing connectivity through text-messaging, e-mail, or video communications to pass along information quickly. In this way, the tablet can serve as a medium for passing along sufficient data to provide early warning.

Over the next decade, however, a tablet-sized platform may encroach on the role of larger and smaller platforms. Industry is investing billions of dollars in research and industrial solid-state manufacturing capabilities to generate a hybrid platform with a tablet’s size but with capabilities even more powerful than today’s conventional desktop computers.

Another promising area of development lies in secure communications. Commercially available, though not yet in wide use, quantum key distribution (QKD), a subset of quantum cryptography, uses quantum communications to securely exchange a key between two or more parties or devices in which there is a known risk of eavesdropping. Because quantum mechanics guarantees that measuring quantum data disturbs the data, QKD can establish a shared key between two parties without a third party surreptitiously learning anything about the key being exchanged. Therefore, if a third party attempts to learn the bits that make up the key, it will disturb the quantum data that makes up the key and be detectable, allowing the communicating parties to retry or resort to alternative means.

Findings and Recommendations

The design principles and technology developments noted above led the group to recommendations regarding the PDB tablet’s general architecture, ability to store or access materials, search features and visualization capabilities, note-taking features, and security.

The chosen architecture should enable flexibility, commonality, and reliability.

Wired and wireless devices and networks. Key elements of the PDB should be accessible and deliverable on a range of platforms (smart phones, tablets, desktops, etc.), whether connected via Ethernet cable or a secure and encrypted wireless network.

Synchronizing. PDB content should be synchronized across platforms to ensure version control, even if certain principals may see a different view as a result of their respective roles. The current version should note wherever possible how it may deviate significantly from previous reports.

Remote display. Content should display uniformly across various platforms, e.g., from a handheld to a wall-mounted display.

Paired relationship. To facilitate a shared experience, the software underlying the PDB should allow either the principal or the briefer to “drive” the interaction, maintaining one screen view for both (and any other authorized attendees as well).

Private Cloud and metadata tagging. The PDB’s primary content should be housed on a private Cloud network that allows the production staff and principals to use a single repository. All PDB items should have extensive metadata tagging to facilitate use as well as control access. This Cloud should be connected to most intelligence sources via one-way tunnels or pipes.

Government-owned software. The underlying software should be government owned but constructed with as much functionality as possible from commercial or open sources. It should allow for continuous and seamless upgrades.

24/7 Ownership. Principals should “own” and store their own PDB device where practicable, rather than have it bestowed on them by the IC for a short time.

Annotation and Feedback. The PDB device should be more than just a stuffed briefcase; it is a vehicle for engagement.

Notetaking. Briefers should be able to conveniently make electronic notes in real time, noting where principals pause, make comments, or otherwise react.

Feedback. Principals should be able to provide direct electronic feedback and receive direct responses in return.

Follow-on action. Principals should be able to make notes to themselves and share an article or piece of information (and their reactions) with authorized staff or fellow senior officials.

Tasking. Principals should be able to task the IC—or even a specific IC element—directly and immediately.

Access. The PDB device should have access to a broad range of materials to support and provide context for finished analysis.

PDF Tablet Wish List

The PDB should be loaded up with referential material including CIA’s The World Factbook, the WIRe, MEDIA highlights, NCTC Terrorism Situation Report, maps, imagery, SIGINT, GEOINT, HUMINT, OSINT, key historical Intelligence, and more.—Several current PDB recipients

The PDB needs a search capability.—Several current PDB recipients

To summarize the critical success factors for the PDB [electronic tablet]—it must be authoritative, useful, complete, and easy to use. —Senior Leader, PDB staff

Wireless access is key to our success. —Senior Leader, PDB Staff

I think we need to mesh e-mail, 24 hour updates, PDB and all other classified information electronically. —Senior White House official

Open source is often highly relevant and it should be in the PDB device for access during the briefing and for later reference but it may not be the entire picture and it is often biased one way or another (e.g., the New York Times, the Washington Post, the Wall Street Journal). —Current PDB recipient

Why can’t the PDB device have a secure docking station at the recipient’s location so that it can be charged with intelligence each morning before the briefer arrives and then updated for later reference during the day? —Senior White House official

Access to original source Intelligence is the most frequently asked question by principals who receive the PDB. —Senior Leader, PDB staff

The interactive displays and simulations are a great way to communicate effectively and quickly. —Senior White House official

Human factors and individual differences in cognitive style and interaction style need to be considered to achieve the flexibility, adaptability and agility needed for a suitable PDB technical platform. —Senior White House official

It would be neat to have a variety of [video] news feeds on subjects you are interested in so that you could multitask in the office during the day—to include potentially the TED series, summaries, key facts, depending on the interests of the specific principal. —Current PDB recipient

Classified/sensitive sources. The PDB should allow principals to link to as much standard finished intelligence information as possible and to include biographical information on individuals cited; empirical data on organizations and states; and economic and financial data. It should tailor access to more specific resources, e.g., recent NIEs or relevant collection reports. Where a PDB piece relies on finished analysis or formal collection reports, hotlinks should be available. Providing principals and other designated leaders with access to raw collection data should be avoided in most cases as the potential hazards will often far outweigh benefits. [3] Also, there is value to giving the PDB Staff the ability to customize answers to questions that come back from principals about daily PDB issues.

Open sources. The PDB device should have robust access to open sources so that principals and briefers can share common contexts. Sources should range from major media to other open-source (and Open Source Center) products, again potentially positioning the tablet as the IT device of choice for senior officials. But the PDB should not become an alternative portal to open-source information that is easily available from other channels such as television, newspapers or magazines.

Previous PDB briefs. Briefers and principals should be able to pull up previous briefs to see what has changed or remained constant on an issue, or how it might relate to other issues.

IC experts. Briefers and principals should be able to connect with a relevant IC officer to pose more specific questions and engage more deeply, especially in time-critical circumstances.

Search. The PDB software should provide robust discovery capabilities that let users make additional connections and generate further insights.

Full-text. The PDB software should allow full-text searches on key terms or phrases to allow recipients to readily find items of interest.

Commercial algorithm-based. The PDB software should make use of commercial search algorithms on sources cited to indicate popularity, e.g., “People who consulted this item, also consulted, a, b, and c.”

Limited natural language query. PDB software should allow natural language queries typical in commercial search engines so that relevant data are discoverable.

Security. The PDB system must adopt a more robust security apparatus that can work in a portable, wireless, multi-security-level environment.

Biometrics. Access to a PDB device should be granted through biometric signatures or mobile device tokens, not just physical handling and passwords (if feasible among this challenging user community).

Access control and authorization. PDB users accessing online content should have rigorous authentication procedures to verify their credentials. This is especially important when the tablet is used to share or engage on tablet content with others.

Encryption. All communication via a PDB platform should be encrypted to TOP SECRET standards but without unnecessary user distraction or inconvenience.

Multilevel access. The PDB network should be able to readily and securely “stare down” into networks of lower classification and securely bring content up to networks of higher classification. It should also be cognizant of compartmented programs—even if security may prevent accessing the information on the tablet—so that recipients can see that content of interest exists and may be available using other means.

Discretionary access control. PDB items should have the equivalent of “tear-lines” so that principals can benefit from certain content, even if classification constraints do not permit access to further details or sources.

Kill/self-destruct feature. PDB devices should have software that allows certain information to be wiped from the device upon principal or briefer direction or have a device to self-destruct if it is thought to be compromised or in danger of capture. If extreme acceleration is detected by the tablet or platform’s accelerometers, for instance in the event of a car crash, the self-destruct feature should automatically activate.

Updating Securely. The PDB must be in a highly secure location whenever PDB contents are being displayed or updated. Further it must be connected to the PDB updating network (or Cloud) through a special hardwired, photonic, or RF mechanism to assure secure operations for the update.

PDB Tablet as a Full Featured Information Support Device. The device should evolve from a single-purposed platform usable only for a short window of the day (as it is for the current PDB experiment) to an information-support device that principals incorporate into the range of their daily routines.

E-mail. The PDB tablet should have government e-mail functionality (potentially unclassified as well as classified) so that principals can send messages based on insights from the intelligence support they receive. But outgoing PDB content should not be allowed unless there is a guarantee that the recipient has authorized PDB information access (as in a principal to principal communication).

Calendar. Principals should have access to their calendars and to those of others, along with reminder and note-taking functions.

Web. Principals should be able to access Internet services (potentially unclassified as well as classified). Access to Intelink would be of tremendous value.

Live Connection. Principals should be able to achieve secure connection with peers by video or live-chat.

Impact on Process and Culture

The combination of the tablet, visualization techniques, robust and accessible knowledge bases, and sophisticated applications makes possible dramatic change in the relationships between PDB recipients and the intelligence officers who produce and deliver intelligence. Such a shift would lead to major changes in IC processes and culture.

A major shift would be movement from the provision of “finished” analytic products in relatively staged, controlled interactions to the creation of more dynamic relationships between producer and recipient of intelligence. With fully capable tablets, PDB recipients could have access to numerous amplifying sources, visuals, and multimedia; receive continuous updates; provide feedback more readily and comprehensively; and extend their reach via other communication capabilities almost immediately.

The impact on process would also be palpable. The daily rhythm of intelligence analysis and production would no longer resemble old-fashioned newsrooms that surge before “print” time. Instead, there would be a continuous drumbeat of activity around creating material in various media: hard copy, mp3, video, web, etc. The 24/7-level of required staffing for such an operation would certainly increase demand for resources.

Using a visually intensive technology requires significant changes to the analytic process. The technology would place a premium on the creation of substantive visualizations, especially in the early development of analytic products, and multimedia manipulation. The IT infrastructure will have to support queries for both analytic products and collection reports. Quality control methods must morph to allow continuous, 24/7 improvement to reflect ongoing streams of reporting.

In the course of our research, we observed that the PDB process and content vary considerably from one recipient to another (we interviewed 15 of the current 30 or so PDB recipients—principals and other senior leaders), and the amount of time principals spend on the PDB on a given day will vary based on the interest in the topics of the day, and how busy they feel.

CEOs who use decision-support capabilities in the private sector typically want all or most of their senior leadership (direct reports and sometimes the next layer) to be well informed on issues the CEOs care about so that the next level or two can actively participate in an informed way if the CEO invites a discussion or debate. We have never seen a situation where the CEO is the only user of their corporate decision-support capability. It seems to us that the same logic should very well apply to the president and to his or her senior leadership team as well as to the PDB.

The cultural transformation is equally significant. The PDB is among the most tightly controlled processes in the US national security establishment. The tablet and other related visualization technologies challenge this premise by allowing PDB recipients and IC officers to engage more directly and more frequently in more interactive and dynamic partnerships. An important task for the IC will be to keep the content lively and fresh.

Regardless, the DNI and the briefers should retain regular face-to-face interaction with PDB recipients to ensure the IC is duly supporting senior leaders and to avoid the loss of the valuable and critical human element provided by the interaction of briefers and principals.

The Future of the Briefer

A panel of past and present PDB briefers was asked to discuss the future of briefers in the decision-support environment. In general, panelists were confident that fears of radical changes in the personal interaction between PDB recipients were unfounded and that the relationship would endure. They also felt there would be no change in the core features of today’s PDB briefer. Mutual trust, knowledge of subjects, ability to anticipate needs and questions, and ability to quickly get answers to questions would remain bedrocks of the relationship.

The panelists also dismissed concerns that failed past efforts to introduce similar technological shifts would be a factor today. Indeed, most panelists felt the recipients of the today’s PDB are ready for radical changes. They also dismissed concerns that briefers would become obsolete because of technological developments.

Finally, the panelists did concede that briefers would have to develop some new skills to work in the environment. These are mainly in the area of learning to work more effectively with visualizations and other graphics and multimedia products. (See table below for a selection of comments.)

Next Steps

To follow up on these findings, we recommend the IC leadership consider six actions.

Establish a point of contact, supported by a small IC-wide working group, to mine emergent visualization capabilities and their utility for PDB and other IC applications.

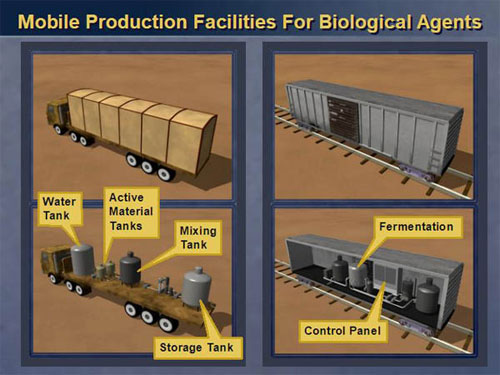

Mobile Production Facilities for Biological Agents

The reason I went to the U.N. is because we needed now to put the case before the entire international community in a powerful way, and that’s what I did that day.

Of course walking into that room is always a daunting experience, but I had been there before. And we had projectors and all sorts of technology to help us make the case. And that’s what I did. I made the case with the director of central intelligence sitting behind me. He and his team had vouched for everything in it. We didn’t make up anything. We threw out a lot of stuff that was not double- and triple-sourced, because I knew the importance of this.

When I was through, I felt pretty good about it. I thought we had made the case, and there was pretty good reaction to it for a few weeks. And then suddenly, the CIA started to let us know that the case was falling apart — parts of the case were falling apart. It was deeply disturbing to me and to the president, to all of us, and to the Congress, because they had voted on the basis of that information. And 16 intelligence agencies had agreed to it, with footnotes. None of the footnotes took away their agreement.

So it was deeply troubling, and I think that it was a great intelligence failure on our part, because the problems that existed in that NIE should have been recognized and caught earlier by the intelligence community.

-- Colin Powell: U.N. Speech “Was a Great Intelligence Failure”, by Jason M. Breslow

External experts such as those interviewed for this project would be ideal sources of insights about current practices, hardware and software developments, and cutting-edge R&D initiatives. This working group should also assess the impact of visualization techniques on the production process in each IC element and the IC as a whole. This POC would be responsible for the next three actions.

PDB Briefers: Success Factors Unique to Tablet Environment

Skills Likely to be Needed

• The ability to think in words and pictures and explain issues using graphics and visualization tools

• Ability to recognize and plan effective visualizations for upcoming briefings

• Storyboarding skills using words, pictures, video and other multi-media tools

• Ability to locate and store reference and source material of potential interest

• Ability to work with technical experts in producing and displaying multi-media

• Ability to think of self as curator of vast quantities of relevant intelligence knowledge and information

• Skill in helping principals become more proficient in their use of the tablet

Downside Fears:

• Principals will make flawed decisions based on non-authoritative or inadequately vetted information available on a tablet.

• Principals will become frustrated, overloaded or overwhelmed by too much data.

• The tablet would negatively affect the quality of the briefer/principal relationship.

• Previous attempts to introduce similar technologies portend another failure.

• Briefers will become obsolete.

Develop a high-level strategic roadmap and implementation plan. These recommended changes in the PDB are complex and interdependent. They require an integrated approach and leadership commitment to ensure technologies are inserted and accompanied by appropriate changes in processes. (In contrast, the operational planning, control, and rollout process is expected to be an evolutionary learning and prototyping approach that would exploit insights from the experimentation and working group activities and over time from the R&D program mentioned below).

Conduct a series of experiments to test emergent capabilities and their implications for the user experience, the production model, and IC culture.

The experiments should be conducted in the context of a rapid evolutionary prototyping lab using the best available commercial-quality software and hardware test beds so that capabilities can be properly tested, evaluated, and red-teamed. IARPA, CIA’s Directorate of Science and Technology, and/or NSA’s Technology and Research Directorates may be well suited to assist in these experiments.

Develop technology insertion tactical plans for each major phase or cycle of new capability development. These plans should be vetted by the IC working group described above. They should describe in detail how to accomplish needed improvements and estimated implementation costs. These project-level plans will be derived in part from ongoing learning processes.

Establish and develop an R&D program of record. Given the dynamic nature of computing, communication, analytic, and visualization technologies, the DNI should create an IC-wide R&D effort that continuously plumbs emergent ideas that would benefit the PDB and perhaps many other potential user sets in IC leadership positions. This need not be a large effort, but it should draw from across the IC.

Consider extending the findings of the above efforts to other senior users of intelligence. The ideas generated in this paper have applicability beyond the PDB and deserve attention for how they can enhance intelligence support to other officials across the US government.

Conclusion

Implementing these recommendations will not be easy or free and should not be underestimated, but in our judgment conversion of the current PDB system into one that more closely resembles an advanced decision-support and executive-information system will provide opportunities to improve the efficiency and effectiveness of the production process itself, opportunities that should not be passed up.

The ethos of the PDB rests in its heritage as a compilation of largely finished analysis for a dedicated senior reader, delivered on a schedule, by a skilled intelligence briefer, who serves as the gateway to the rest of the IC. An elaborate production process and supporting analytic cadre have institutionalized that model and the culture in which it is produced. It has fostered a highly regulated production scheme for producing serial, fixed outputs controlled by the IC.

The use of electronic tablet technologies used to their fullest capabilities portends a process of shared discovery between the principal and the broader IC, a model that is nothing short of a paradigm shift, a shift likely to meet considerable resistance.

To reduce potential resistance, it is critical that new capabilities not invade the “personal space” of PDB recipients and that the option to retain a paper product remains. In addition past efforts to introduce new technology to the process of informing policymakers should be examined to draw applicable lessons from those experiences.

If the PDB is to evolve in this direction, it must be done systematically and deliberately, with fierce intent and courageous patience to overcome challenges from those unsettled by the changes and the complexity of the technology and the service it is intended to perform.

A strategic plan will be necessary to identify how desired functions will be introduced and how challenges will be met. The changes, however, do not have to be implemented all at once and can be phased in over time, and there is time to adapt approaches to many potential PDB users.

Failure to begin the journey outlined in this paper in a timely way—with some noticeable degree of urgency and focus—may jeopardize the progress made so far with the current PDB tablet experiment, which we judge to be successfully providing insights into what will be needed in the future. PDB recipients (especially principals) appear to want more than they are currently getting, and they may revolt against the tablet and other forms of new technology if they perceive that they are not reaping the technology’s potential benefits. The lost momentum could cause the PDB to retreat to the “business as usual” status of the last 40 years. Such a development would represent a significant missed opportunity.

_______________

Notes:

1. Nothing in this paper should be interpreted to suggest that we believe a tablet is the only relevant computer-based device that has a role to play in providing access to and use of intelligence information for the PDB or any other purpose.

2. For detailed discussion of the approaches presidents up to 2004 have had toward the PDB, see John L. Helgerson, Getting to Know the President: Intelligence Briefings of Presidentitial Candidates, 1952–2004 (CIA, Center for the Study of Intelligence, 2012). An free audio version is available at http://www.gpo.gov/fdsys/pkg/GPO-CIA-Ge ... ePresident

3. Hazards include principals lacking the context to properly interpret the data; principals getting consumed or frustrated in perusing voluminous traffic; principals not understanding how to request the right data; and the ever present risks of security and handling violations.

All statements of fact, opinion, or analysis expressed in this article are those of the authors. Nothing in the article should be construed as asserting or implying US government endorsement of its factual statements and interpretations.