Fulton County DA seeks to keep potential juror identities secret in election interference case

by Sara Murray

CNN

Published 6:25 PM EDT, Wed September 6, 2023

Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis wants to keep the identities of jurors who may be chosen to hear the Georgia 2020 election interference case secret, after grand jurors who issued the indictment against Donald Trump and his allies were doxed online, according to a new court filing.

Willis is asking the court to “issue an order restricting any Defendant, members of the press, or any other person from disseminating potential jurors’ and empanel jurors’ identities during voir dire and trial,” according to the Wednesday filing.

“Based on the doxing of Fulton County grand jurors and the Fulton County District Attorney, it is clearly foreseeable that trial jurors will likely be doxed should their names be made available to the public,” according to the filing. “If that were to happen, the effect on jurors’ ability to decide the issues before them impartially and without influence would undoubtedly be placed in jeopardy, both placing them in physical danger and materially affecting all of the Defendants’ constitutional right to a fair and impartial jury.”

CNN previously reported that names, photographs, social media profiles and even the home addresses purportedly belonging to members of grand jury who voted to indict Trump and his 18 co-defendants circulated on social media.

The names of the grand jurors were included on the indictment as a matter of practice for indictments in Fulton County. However, the indictment, which is a public record available on the court website, does not include their addresses or any other personally identifiable information.

Doxing the grand jurors who voted on the indictment “resulted in law enforcement officials, including the Atlanta Police Department, Fulton County Sheriff’s Office, and other police departments in the jurisdiction, putting plans in place to protect the grand jurors and prevent harassment and violence against them,” the district attorney’s office said in the filing.

It notes that personal information for Willis and members of her family was also shared online.

In an affidavit included with the filing, an investigator in the district attorney’s office said he worked with the Department of Homeland Security to determine that the site that listed the personal information for Willis and her family members was hosted by Russia “and is known by DHS as to be uncooperative with law enforcement.”

Clearly foreseeable trial jurors will likely be doxed - GA.

6 posts

• Page 1 of 1

Re: "Clearly foreseeable that trial jurors will likely be do

What is doxxing and what can you do if you are doxxed?

by Sen Nguyen

CNN

9/8/23

(CNN) In 2017, Kyle Quinn enjoyed the anonymity any engineering professor typically would until he became a target of doxxing. Angry social media users mistakenly identified him as having attended a White nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. His pictures, home address and employer's name quickly made rounds across social networks, frightening Quinn and his wife and sending them to a colleague's home for refuge, the New York Times reported.

Quinn is one of many victims of doxxing, a form of online invasion of personal privacy that can lead to devastating consequences.

What is doxxing?

According to the International Encyclopedia of Gender, Media, and Communication, doxxing is the intentional revelation of a person's private information online without their consent, often with malicious intent. This includes the sharing of phone numbers, home addresses, identification numbers and essentially any sensitive and previously private information such as personal photos that could make the victim identifiable and potentially exposed to further harassment, humiliation and real-life threats including stalking and unwanted encounters in person.

Why is it called doxxing?

There are multiple etymologies for the term, but the cybersecurity firm Kapersky reports that one explanation is that doxxing came from the phrase ''dropping documents'' and gradually ''documents'' became ''dox'' which has been used as a verb to refer to the practice. Originally a form of online attack used by hackers, the firm wrote, doxxing has been around since the 1990s.

What are other examples of doxxing?

Doxxing can happen in many ways online and on other platforms.

According to the International Encyclopedia of Gender, Media, and Communication, in 2014, the gaming industry experienced a watershed moment known as Gamergate, a year-long culture war led by far right trolls online. After Eron Gjoni, ex-boyfriend of game developer Zoe Quinn uploaded a blog post about their break up, accused her of cheating on him, and shared screenshots of their private communications on an online forum, Quinn became one of many gamers to be a high-profile target of doxxing and rape threats, followed by many other female game developers who raised their voices, according to The Guardian.

One of the victims, the American game developer Brianna Wu wrote in the magazine Index on Censorship: ''The truth is there is no free speech when speaking about your experiences leads to death threats, doxxing and having armed police sent to your house.'

In 2014, Wu tweeted about escaping her home out of fear for her safety along with screenshots of death threats sent to her account.

In 2019, the South African journalist and broadcaster Karima Brown missent a message meant for her producer to a WhatsApp group run by the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) political party in which journalists are able to get media statements from the EFF, according to the Committee for the Protection of Journalists (CPJ). Julius Malema, the party leader, accused her of spying on the party, and reacted by tweeting her phone number to his 2.3 million followers. Brown reportedly received rape and murder threats, including graphic messages. The high court in Johannesburg later ruled the doxxing was a violation of the country's Electoral Act, according to the CPJ, with Brown telling the non-profit that the court's ruling was "a victory for democracy and media freedom, and a blow against misogyny and toxic masculinity."

How and where can you report doxxing?

Facebook's parent company Meta does not explicitly use the term ''doxxing'' in its privacy violations policy, but said in a statement to CNN that it considers users sharing ''personally identifiable information'' about others a violation of its community standards. The company says it reviews any piece of content against its community standards and may remove private information such as home addresses that could result in tangible harm unless this information is publicly available through news coverage, press releases or other sources. Facebook users can use a specific reporting channel when they are concerned about their image privacy on the platform.

TikTok clearly defines doxxing in its community guidelines which ban both the collection and publication of individuals' personal information for malicious intent. Users can report a specific item on the platform and follow the instructions.

Twitter's app and desktop versions allow you to report other users who tweet private information and media about themselves or somebody else without permission by clicking on the three dots in the corner of an offending tweet, then Report Tweet and following the instructions. Users found in violation of the policy are required to remove the content in question and temporarily locked out of their account. Twitter says permanent suspension may result from a second violation. Users can also file a separate form to report such violations.

Is doxxing illegal and can you be arrested for doxxing?

It depends on the jurisdiction. In Asia, Singapore outlawed most forms of intentional harassment or distress in 2014, which includes doxxing, and violators can be fined up to SGD $5,000 (nearly $3,800 US) and/or jailed for up to 6 months.

In Indonesia, activists told CNN that doxxing cases have been on the rise, especially those targeting women human rights defenders and journalists. Damar Juniarto, the executive director of Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network, a network of digital rights activists, said the term doxxing ''is not known in the Indonesia legal system'' causing some doxxing cases to not be taken seriously by police. But he explained that the Personal Data Protection law, passed in September, punishes people who use and share personal information without a person's consent, which can include doxxing.

In the UK, there are clear guidelines for prosecutors to handle cases, particularly cases of violence against women and girls, which involve threats to post personal information on social media and the disclosure of private sexual images without consent, and the punishments vary.

In the US, measures to combat doxxing vary across states. Last year, Nevada passed a bill that bans doxxing and allows victims to bring a civil action against the perpetrators. In California, cyber harassment including doxxing with the intent to put others and their immediate family in danger can put violators in county jail for up to one year or impose a fine of up to $1,000, or both.

In 2021, Hong Kong authorities amended the data privacy law to include doxxing, with people facing jail sentences of up to five years and fines of up to HK$1 million ($129,000 US). This followed the doxxing of many officials and police officers during the 2019 protests against the Hong Kong government's proposed bill to allow extraditions to mainland China. Critics argued that doxxing can be legally defended if sharing information about government officials out of public interest.

Lauren Krapf, the technology policy and advocacy counsel for the Anti-Defamation League in the US, said whether doxxing is criminal depends on the intent.

''I think in certain circumstances, it is probably appropriate that [doxxers] have some level of criminal liability or civil liability," Krapf told CNN, but emphasized that doxxing is not a black and white situation. The activity itself can be an empowerment tool for people engaging in protests to share information about extremists to others, she explained.

Across the US, "state laws vary greatly and there is no federal statute outlawing doxxing," Krapf told CNN, meaning "there isn't currently one specific standard codified."

Does doxxing affect more women than men?

While anyone can be doxxed, experts believe women are more likely to be targets of mass online attacks, leaks of their sensitive media, such as sexually explicit imagery that was stolen or shared without consent and unsolicited and sexualized messages.

A 2020 report by UN Women focusing on India, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippines, and South Korea found that women experience many forms of online violence simultaneously such as trolling, doxxing and social media hacks.

A 2020 global report by The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), found that online violence against women is startlingly prevalent in the 51 countries surveyed, with 45% of Generation Z and Millennial women reporting being affected, compared to 31% of Generation X women and Baby Boomers, while 85% of women surveyed overall report witnessing online violence against women. While online violence is alarmingly common globally, the study shows significant regional differences, with Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Middle East showing at least 90% of women surveyed having been affected.

How can you protect yourself against doxxing?

While the responsibility to prevent doxxing rests with those who would violate another's privacy, and not with the victim, it is useful to take some preventative steps to protect yourself online.

It can help to be familiar with doxxing-related policies on the online platforms you use as well as how to report abuse more generally. Consider making it harder for people to track you online by restricting the accessibility of any information that can identify you online and offline. For example, check who can see your personal email, phone number, home addresses and other physical locations on your social media accounts.

The University of Berkeley, PEN America and Artist at Risk Connection provide thorough online privacy guides.

by Sen Nguyen

CNN

9/8/23

(CNN) In 2017, Kyle Quinn enjoyed the anonymity any engineering professor typically would until he became a target of doxxing. Angry social media users mistakenly identified him as having attended a White nationalist rally in Charlottesville, Virginia. His pictures, home address and employer's name quickly made rounds across social networks, frightening Quinn and his wife and sending them to a colleague's home for refuge, the New York Times reported.

Quinn is one of many victims of doxxing, a form of online invasion of personal privacy that can lead to devastating consequences.

What is doxxing?

According to the International Encyclopedia of Gender, Media, and Communication, doxxing is the intentional revelation of a person's private information online without their consent, often with malicious intent. This includes the sharing of phone numbers, home addresses, identification numbers and essentially any sensitive and previously private information such as personal photos that could make the victim identifiable and potentially exposed to further harassment, humiliation and real-life threats including stalking and unwanted encounters in person.

Why is it called doxxing?

There are multiple etymologies for the term, but the cybersecurity firm Kapersky reports that one explanation is that doxxing came from the phrase ''dropping documents'' and gradually ''documents'' became ''dox'' which has been used as a verb to refer to the practice. Originally a form of online attack used by hackers, the firm wrote, doxxing has been around since the 1990s.

What are other examples of doxxing?

Doxxing can happen in many ways online and on other platforms.

-- A victim of Gamergate organized a SXSW summit to fight online threats against women, by Leanna Garfield

-- Brianna Wu and the Human Cost of Gamergate: "Every Woman I Know in the Industry is Scared," by Keith Stuart

-- #GamerGate Trolls Aren't Ethics Crusaders; They're a Hate Group, by Jennifer Allaway

-- Let's Talk About Zoe Quinn's Ex For Once, by Lindsey Weedston

According to the International Encyclopedia of Gender, Media, and Communication, in 2014, the gaming industry experienced a watershed moment known as Gamergate, a year-long culture war led by far right trolls online. After Eron Gjoni, ex-boyfriend of game developer Zoe Quinn uploaded a blog post about their break up, accused her of cheating on him, and shared screenshots of their private communications on an online forum, Quinn became one of many gamers to be a high-profile target of doxxing and rape threats, followed by many other female game developers who raised their voices, according to The Guardian.

One of the victims, the American game developer Brianna Wu wrote in the magazine Index on Censorship: ''The truth is there is no free speech when speaking about your experiences leads to death threats, doxxing and having armed police sent to your house.'

In 2014, Wu tweeted about escaping her home out of fear for her safety along with screenshots of death threats sent to her account.

In 2019, the South African journalist and broadcaster Karima Brown missent a message meant for her producer to a WhatsApp group run by the Economic Freedom Fighters (EFF) political party in which journalists are able to get media statements from the EFF, according to the Committee for the Protection of Journalists (CPJ). Julius Malema, the party leader, accused her of spying on the party, and reacted by tweeting her phone number to his 2.3 million followers. Brown reportedly received rape and murder threats, including graphic messages. The high court in Johannesburg later ruled the doxxing was a violation of the country's Electoral Act, according to the CPJ, with Brown telling the non-profit that the court's ruling was "a victory for democracy and media freedom, and a blow against misogyny and toxic masculinity."

How and where can you report doxxing?

Facebook's parent company Meta does not explicitly use the term ''doxxing'' in its privacy violations policy, but said in a statement to CNN that it considers users sharing ''personally identifiable information'' about others a violation of its community standards. The company says it reviews any piece of content against its community standards and may remove private information such as home addresses that could result in tangible harm unless this information is publicly available through news coverage, press releases or other sources. Facebook users can use a specific reporting channel when they are concerned about their image privacy on the platform.

TikTok clearly defines doxxing in its community guidelines which ban both the collection and publication of individuals' personal information for malicious intent. Users can report a specific item on the platform and follow the instructions.

Twitter's app and desktop versions allow you to report other users who tweet private information and media about themselves or somebody else without permission by clicking on the three dots in the corner of an offending tweet, then Report Tweet and following the instructions. Users found in violation of the policy are required to remove the content in question and temporarily locked out of their account. Twitter says permanent suspension may result from a second violation. Users can also file a separate form to report such violations.

Is doxxing illegal and can you be arrested for doxxing?

It depends on the jurisdiction. In Asia, Singapore outlawed most forms of intentional harassment or distress in 2014, which includes doxxing, and violators can be fined up to SGD $5,000 (nearly $3,800 US) and/or jailed for up to 6 months.

In Indonesia, activists told CNN that doxxing cases have been on the rise, especially those targeting women human rights defenders and journalists. Damar Juniarto, the executive director of Southeast Asia Freedom of Expression Network, a network of digital rights activists, said the term doxxing ''is not known in the Indonesia legal system'' causing some doxxing cases to not be taken seriously by police. But he explained that the Personal Data Protection law, passed in September, punishes people who use and share personal information without a person's consent, which can include doxxing.

In the UK, there are clear guidelines for prosecutors to handle cases, particularly cases of violence against women and girls, which involve threats to post personal information on social media and the disclosure of private sexual images without consent, and the punishments vary.

In the US, measures to combat doxxing vary across states. Last year, Nevada passed a bill that bans doxxing and allows victims to bring a civil action against the perpetrators. In California, cyber harassment including doxxing with the intent to put others and their immediate family in danger can put violators in county jail for up to one year or impose a fine of up to $1,000, or both.

In 2021, Hong Kong authorities amended the data privacy law to include doxxing, with people facing jail sentences of up to five years and fines of up to HK$1 million ($129,000 US). This followed the doxxing of many officials and police officers during the 2019 protests against the Hong Kong government's proposed bill to allow extraditions to mainland China. Critics argued that doxxing can be legally defended if sharing information about government officials out of public interest.

Lauren Krapf, the technology policy and advocacy counsel for the Anti-Defamation League in the US, said whether doxxing is criminal depends on the intent.

''I think in certain circumstances, it is probably appropriate that [doxxers] have some level of criminal liability or civil liability," Krapf told CNN, but emphasized that doxxing is not a black and white situation. The activity itself can be an empowerment tool for people engaging in protests to share information about extremists to others, she explained.

Across the US, "state laws vary greatly and there is no federal statute outlawing doxxing," Krapf told CNN, meaning "there isn't currently one specific standard codified."

Does doxxing affect more women than men?

While anyone can be doxxed, experts believe women are more likely to be targets of mass online attacks, leaks of their sensitive media, such as sexually explicit imagery that was stolen or shared without consent and unsolicited and sexualized messages.

A 2020 report by UN Women focusing on India, Malaysia, Pakistan, the Philippines, and South Korea found that women experience many forms of online violence simultaneously such as trolling, doxxing and social media hacks.

A 2020 global report by The Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU), found that online violence against women is startlingly prevalent in the 51 countries surveyed, with 45% of Generation Z and Millennial women reporting being affected, compared to 31% of Generation X women and Baby Boomers, while 85% of women surveyed overall report witnessing online violence against women. While online violence is alarmingly common globally, the study shows significant regional differences, with Africa, Latin America and the Caribbean, and the Middle East showing at least 90% of women surveyed having been affected.

How can you protect yourself against doxxing?

While the responsibility to prevent doxxing rests with those who would violate another's privacy, and not with the victim, it is useful to take some preventative steps to protect yourself online.

It can help to be familiar with doxxing-related policies on the online platforms you use as well as how to report abuse more generally. Consider making it harder for people to track you online by restricting the accessibility of any information that can identify you online and offline. For example, check who can see your personal email, phone number, home addresses and other physical locations on your social media accounts.

The University of Berkeley, PEN America and Artist at Risk Connection provide thorough online privacy guides.

- admin

- Site Admin

- Posts: 36180

- Joined: Thu Aug 01, 2013 5:21 am

Re: "Clearly foreseeable that trial jurors will likely be do

They released a sex video to shame and silence her. She's one of many women in Myanmar doxxed and abused on Telegram by supporters of the military

by Pallabi Munsi

CNN

9/8/23

(CNN) In the summer of 2021, Chomden was abroad, thousands of miles away from her home in Myanmar, when a friend sent her an urgent message informing her that an intimate video of her was being shared online.

When she saw the message, the 25-year-old said she froze "like a statue," her phone falling from her hand. She had just been doxxed.

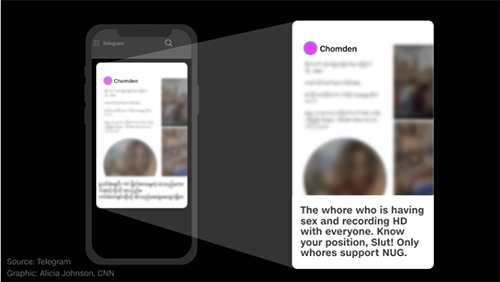

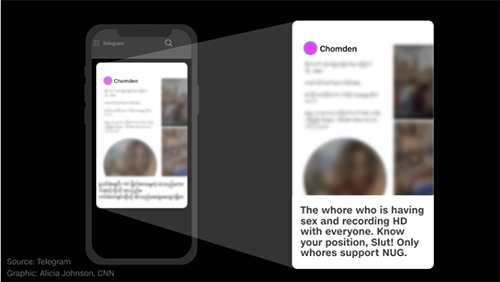

A video of a naked Chomden -- whose name has been changed to protect her identity -- having sex with a former boyfriend, along with her name and Facebook profile picture, was circulating on a public channel on the messaging platform Telegram, and many of the group's approximately 10,000 followers had begun sending her abusive messages.

It had been just six months since Myanmar's civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi was removed from power in a military coup led by General Min Aung Hlaing, who set up the State Administration Council (SAC) and now governs the country's caretaker government as an unelected prime minister.

Chomden had been on holiday at the time of the February 1 coup, and felt too scared to return home, but she says she had also felt obligated to speak out on social media about the plight of Myanmar's people and the junta's swift and brutal repression of critical voices, sharing video testimonies from people still in the country.

Far away from home, she had assumed she would be safe from any reprisals for her criticism of the ruling junta, but Chomden had not considered the possibility of online retribution.

Now, months after the coup, her once private video had been made public -- on a channel run by supporters of the military and used to circulate propaganda and dox people believed to oppose the SAC. Chomden's Facebook picture included a filter showing the flag of Myanmar's shadow government, the National Unity Government (NUG), identifying her as a supporter of the country's deposed, democratically elected government.

The accompanying text on the Telegram post, written in Burmese by the channel administrator, read: "The whore who is having sex with everyone and recording it in HD... Know your position, slut!"

She was also blackmailed by strangers claiming to have more videos of her, she says, and with no support system nearby, Chomden felt lost. The fallout from the post took such a toll on her mental health that she said: "I have to admit that I even thought of killing myself."

"They wanted to destroy my life," she told CNN.

Thousands of "politically active" women doxxed or abused

After the coup two years ago, as state repression intensified, civilians came together to defend towns and villages, and some rebel armies with a long history of conflict against the military united under the People's Defence Force (PDF), armed units aligned with the shadow government.

Fighting has since displaced hundreds of thousands of people and many now fear a deepening civil war.

But conflict in Myanmar is not only happening on the ground; attacks are prevalent online, and doxxing has emerged as a tool used extensively by supporters of the junta to threaten and silence people they see as their opponents.

Doxxing is the act of publicly identifying or publishing "private information about someone as a form of punishment or revenge" -- and men and women are being targeted in different ways.

When men are targeted, posts typically insinuate that they are linked to terrorist groups working to bring down the junta, multiple experts from NGOs and digital rights groups in the region told CNN. But when women are doxxed, the attacks frequently feature sexist hate speech, often coupled with explicit sexual imagery and video footage of them, as was Chomden's experience.

And in Myanmar, simply sharing the names and faces of people purported to support democracy can put those people at risk of arrest, while exposing private videos and photos subjects them and their entire families to societal shame.

Separate analyses by CNN and NGOs working in Myanmar shows this is all happening extensively on Telegram (which grew in importance after the military ordered Facebook to be temporarily blocked following the coup and has continued to block access since then), and activists are calling on the messaging company's Russian owners to take urgent action to stop this violence being perpetuated through their app.

A CNN analysis identified hundreds of sexual videos and images used in pro-military Telegram channels abusing women, often for having pro-democracy views, and hundreds more using sexual terms to achieve the same goal. A separate analysis by Myanmar Witness -- a project run by the UK-based Centre for Information Resilience that uses open-source tools to uncover human rights abuses -- in collaboration with grassroots organization Sisters2Sisters published recently looked at more than one million Telegram posts following the coup and found further evidence of this.

"We saw that (up to) 90% of the abusive posts were perpetrated by channels that appear to be pro-military and pro-SAC and ultra-nationalist groups ... targeted towards pro-democracy women," Me Me Khant, who led the Myanmar Witness research, told CNN.

A group of women hold torches as they protest against the military coup in Yangon, Myanmar July 14, 2021.

CNN commissioned a data science company with knowledge of Myanmar to analyze ten public pro-military Telegram channels active between the onset of the coup and the end of 2022, identified as containing among the greatest volume of sexual imagery and video footage. CNN is not naming the company because of concerns about their safety. More than 178,000 posts were shared in that timeframe, with one channel having more than 42,000 followers at the time of analysis.

Sexual messages were posted frequently (1,199 posts) and of these, sexually explicit images (204) and sexual videos (187) were common. Almost all of the images and videos (98%) targeted women, often using sexually explicit language in accompanying posts that criticized their pro-democracy views. Chomden's video was circulating in one of the channels analyzed -- almost six months after it was first posted elsewhere.

In a public Telegram channel monitored separately by CNN, misogyny was standard and the release of women's names and addresses commonplace. One post saw an administrator profusely insult a woman for supporting the pro-democracy movement, using offensive sexual language, and questioning her fertility. The post included the lines (originally in Burmese): "Because of her bad attitude, she could not get pregnant." Other posts released addresses calling for women to be found and arrested, or their homes and businesses closed down.

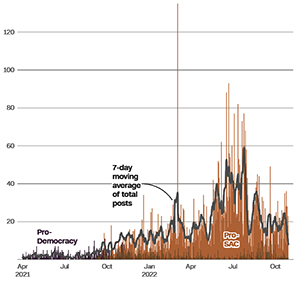

The recent Myanmar Witness report provided further evidence of this abuse online, targeting both prominent women and women in general. The team analyzed more than 1.6 million posts across 100 Telegram channels, which included channels identified as pro-military (64) and pro-democracy (36). Of the channels they observed, posts containing abusive terms targeting women increased eight-fold, from fewer than five posts per day on average in the first months after the February 2021 coup to more than 40 on average by July 2022, with more than 80 abusive posts on some days."

A further analysis of the content of the messages by the non-profit looked at the types of abuse and hate speech in 220 posts across Telegram, Facebook and Twitter (the majority on Telegram) and found that at least half of the posts were doxxing women in apparent retaliation for their political views or actions, the majority targeting women seen as pro-democracy. Of the doxxing posts analysed, 28% included an explicit call for the targeted women to be punished offline. The "overwhelming majority" of abusive posts came from male-presenting profiles supportive of Myanmar's military coup, targeting women who opposed the coup, the report states.

Myanmar Witness highlights in their report that the data gathered during their investigation is "highly likely" to represent just a small sample of politically motivated online abuse aimed at women. The same applies to the CNN analysis, meaning this likely shows just the tip of the iceberg, since the analyses were only of public channels and not private groups or messages.

Multiple experts expressed concern to CNN about links between these channels and the military, and the report goes on to suggest that some pro-military Telegram channels appear to be coordinating with the military itself, doxxing women who oppose it and seeming to make sure the junta is aware of private details that could be used to locate and arrest them. It highlights two cases of women being arrested shortly after being doxxed and of posts celebrating, or claiming credit for, their arrests.

"We've seen two high profile cases where two well-known women were arrested right after being doxxed. The channels also rejoiced after their arrests. When such things happen, you can't help but wonder: what if they weren't doxxed, would they still have been arrested — at the time?," Khant told CNN.

Wai Phyo Myint, Asia Pacific policy analyst at digital rights organization Access Now explains the wide range of significant offline consequences. "People [are] being arrested, blackmailed or forced into exile. Some have lost their livelihoods after their businesses and homes have been sealed off following the doxxing, others have had to go into hiding," she told CNN.

The Myanmar military did not respond to CNN's requests for comment.

Myanmar Witness did see some abuse and doxxing on Telegram channels identifying as pro-democracy, but to a much smaller degree. In response to this, Aung Myo Min, Minister of Human Rights for the National Unity Government acknowledged that gender inequality was a problem in the country. "Harassment based on gender or sexual orientation is very common in Myanmar, on both sides," Myo Min told CNN, adding that "it clearly shows the need (for) work, education and explanation needed on gender equality." But he also called on social media platforms to take action and create a better reporting system. "They have their part (in the) responsibilities," he said.

In a statement to CNN, Telegram spokesperson Remi Vaughn reiterated the Terms of Service and wrote: "Telegram is a platform for free speech. However, sharing private information (doxxing) and calling for violence are explicitly forbidden by our Terms of Service."

CNN was unable to identify clear rules on doxxing in the platform's Terms of Service but did see that the promoting of violence and sharing of illegal pornographic content on "publicly viewable Telegram channels, bots, etc" was prohibited. The platform also provides an email -- abuse@telegram.org -- to report this content.

When CNN followed up with Telegram regarding rules of doxxing -- or the lack thereof -- on their publicly available Terms of Service they did not respond.

Sexual violence as a "targeted weapon"

The Global Justice Center, an international human rights and humanitarian law organization working to advance gender equality, produced a report in 2015 that describes gender stereotypes as pervasive in Myanmar and supported by religious, cultural, political, and traditional practices.

"Women in Burma are generally understood to be secondary to men," the report stated, and in the eight years since its publication, little has changed, believes Akila Radhakrishnan, president of the Global Justice Center.

She believes the mainstream view of women in Myanmar continues to be one of them "being quiet, being docile," and of their bodies seen "as a public collateral," and, in her opinion, the attacks on women in pro-military Telegram groups mirror what the military itself would do.

"The Myanmar military has, for decades, used sexual and gender-based violence as a targeted weapon," Radhakrishnan told CNN. "Women and women's bodies are really viewed in a very narrow mindset by the military, and that reflects on the acts that they perpetrate against women, whether that is physical violence, whether that is other types of violence, the latest being the use of technology."

But women have long played a role in the country's pro-democracy movement, once led by ousted leader Aung San Suu Kyi, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991 for her commitment to the cause. Following the coup, women have been pivotal in organizing pro-democracy protests and experts believe doxxing attacks began and progressively got worse as more women joined these protests.

Anti-coup protesters march in Yangon, Myanmar on March 8, 2022 to mark International Women's Day.

"A woman who is shamed for her body, a woman who is shamed for sexual activities, that means that that woman does not have value within the society anymore," Radhakrishnan said.

After she was doxxed, Chomden told CNN that it was only a matter of hours before she began to be sexually harassed and bullied online. The messages came pouring in, first from strangers abusing her, then, she said, from friends appalled by her "shameful" behavior as word spread across the community.

Chomden said that her mother, still a resident in Myanmar, bore the brunt of the attack: she didn't leave her house for three months out of fear of being shamed and ostracized by people who'd seen or heard about the video.

Chomden continues to support the NUG, but feels scared to return home after the coup, especially since the military had issued an arrest warrant against her for her activism in April 2021, but the video made the idea even more terrifying: "How could I ... with so much shame?," she told CNN.

Getting women to 'censor themselves'

Victoire Rio, a digital rights activist working in Myanmar believes that doxxing is part of a larger strategy to get people to "censor themselves".

"If I should put a timeline to this," Rio told CNN, "you will see that immediately after the coup, the military were going after anybody that had the potential to rally people: that's influencers, movie stars, key activists, sort of local influential figures."

Rio explained that this was done by charging them under penal code 505 for speaking out against the military, which according to Human Rights Watch, was amended to punish a broader range of critics of the coup and the military. But "that wasn't really effective," Rio said.

So, in the summer of 2021, Rio believes there was a change of strategy. "That's when you start seeing doxxing, abuse and targeting extending beyond influential figures, but really starting to target anyone and everyone," said Rio. "It is a campaign of terror [and] a very effective strategy to try to push self-censorship and really try to scare people into silence."

While this cannot be directly linked to the military, the activity is clear in public Telegram channels led by military supporters. Digital rights activist Htaike Htaike Aung, believes the use of sexually explicit content to silence critics has worked. As a result of all the doxxing that has happened, she told CNN: "We see more and more women and gender minorities getting afraid to voice their opinions."

Left no choice but to leave

Linn -- CNN is not using her full name out of concern for her safety -- is a social activist who has been vocal about human rights violations and women's rights in Myanmar since 2017.

She was arrested on March 3, 2021, she told CNN, for organizing non-violent demonstrations following the coup and was held at Insein Prison in Yangon for eight months.

Soon after her release, the 34-year-old, began to speak out about the treatment of incarcerated people in Insein. (A 2021 Human Rights Watch report describes "dehumanizing" experiences of Myanmar prisons, including "sexual violence and other forms of gendered harassment and humiliation from police and military officials" since the coup.)

"I spoke out about violence and human rights abuses in prison on social media and to news media agencies" Linn said. "I also talked and campaigned to strengthen public participation in the revolution."

The military officials who are responsible for Insein prison did not respond to CNN's request for comment.

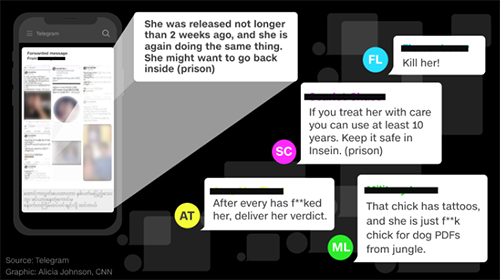

A week after her release, Linn was targeted on a popular pro-military Telegram channel which at the time had over 18,000 followers. Sharing screenshots of her Facebook posts detailing what she said was going on inside Insein, as well as pictures of her with deposed leader Suu Kyi, her doxxer wrote: "She was released not longer than 2 weeks ago, and she is again doing the same thing. She might want to go back inside." Others in the group soon responded with more gendered abuse.

CNN was able to see the abusive posts and the conversation that followed. One user wrote: "Kill her!". Another: "After everyone has f**ked her, deliver her verdict," followed by several more expressing similar sentiments. More posts followed.

Linn had sought refuge at her organization's safe house (which CNN is not naming out of concern for their safety) following her prison release but after being doxxed, it became harder and harder for her to venture outside. "Military supporters and religious extremists started keeping watch in the neighborhoods I was likely to be in," she said.

She told CNN that she was determined not to feel ashamed but was worried about the safety of others. "I knew if I were re-arrested, others living in the safe house would also be targeted."

In March 2022, a year after her ordeal began, Linn snuck out of the safe house and began her journey out of Myanmar. "I did not care if I was re-arrested, I didn't want anyone else to get arrested because of me."

So far from Telegram, little platform accountability

The activity on these Telegram channels can be reported to the platform's moderators and some channels have been taken down as a result. Telegram took down a channel CNN shared soon after it was highlighted, as well as channels highlighted in a recent report by the BBC. But CNN saw that when channels are blocked, new ones soon pop up, and experts highlighted that many harmful ones are never removed.

In January 2022, a digital civil rights organization working in the region (which CNN is not naming to ensure the safety of their teams) listed 14 public Telegram channels that were violating the "human rights of people of Myanmar" in various ways, including the posting of sexually explicit imagery and videos of women without their consent, all launched by a pro-military social influencer who runs multiple channels on Telegram.

The organization say they sent the document -- seen by CNN -- to Telegram, expressing concern that this was happening on its platform, along with a few case studies, calling on Telegram to adhere to UN human rights principles, they told CNN. But one year later, they say they are yet to get a response and say the abuse is continuing to happen in large volumes.

Myint of Access Now highlights that while Telegram has now taken down many channels run by these pro-military influencers, other channels are still running by the same name. "Why is Telegram not being more proactive so as to not let (people with) the same name open more and more channels?,"

Telegram's statement to CNN claimed doxxing, the posting of sexual content and the perpetuation of violence is a violation of its Terms of Service. It also added: "Our moderators use a combination of proactive moderation and user reports to remove such content from our platform. This clear policy has allowed pro-democracy movements around the world to organize large-scale movements safely using our platform, for example in Hong Kong, Belarus and Iran.

But Rio believes Telegram has not played this role in Myanmar. "Telegram claims to be such a revolutionary platform helping Iranians, (and) Hong Kongers but when it comes to Myanmar, it fails to recognize how the platform is abused," she said.

Telegram did not respond to CNN's specific questions on whether it moderates Burmese language content or why abusive, doxxing and pornographic posts on public channels continue despite the platform's Terms of Service.

"We've seen zero efforts from Telegram to reach out to civil society in Myanmar and try to understand what actually is happening," concluded Rio. They need to actually "engage and get a sense for what the risks associated with their platforms are and develop mechanisms to be in a better position to address risks that emerge."

Telegram did not respond to CNN's follow-up request for comment on why it was allegedly not responding to emails and memos from digital rights activists working in Myanmar and showing evidence of large scale doxxing.

Chomden, who felt her life fall apart after being doxxed on one of Myanmar's many pro-military Telegram channels, stresses the need for urgency, saying: "It's not just me, hundreds of women in Myanmar are going through the same and it's not okay. Telegram needs to know it's not alright... to let these groups ruin people's lives."

--------

Hear the testimonies of other women doxxed by pro-military groups

Dr Yin (CNN is not using her full name out of concern for her safety)

Age: 28

Profession: Doctor

Her account has been edited for clarity and brevity

Right after the coup on February 1, 2021, I teamed up with other doctor friends to treat civilians injured during the protests that had erupted. We were determined to treat people in need and within two days, we were running free medical clinics. We also gave reports on the numbers injured -- and killed -- to reporters in the city.

In mid-March, a reporter friend warned me that the military had issued an arrest warrant in my name under Penal Code 505 (A), which had been recently amended and now covered more people speaking critically about the coup and the military. So, I took a bag and fled the country.

After I left, someone I knew posted a video of me along with false information claiming I was having an affair and an even bigger nightmare began.

Pro-military groups had somehow obtained the video, and pictures from my Facebook profile ended up on several Telegram channels run by pro-military groups and the images exposed my location.

Many people started sending rude messages to me, and back home, my mother was humiliated by people in her community who commented that I have a bad character. On my blog, people started commenting that I should be punished for going against Burmese culture (which frowns upon couples living together out of wedlock and on women having affairs).

It all took a massive toll on my life. I no longer use social media because I am so scared. I can't go home, and I do not have any protection where I am because there is an arrest warrant out for me in Myanmar. I am now an illegal immigrant. I feel so hopeless and there is no solution in sight.

***

Thinzar Shunlei Yi

Age: 34

Profession: Pro-democracy activist for Sisters2Sisters

Her account has been edited for clarity and brevity

I have been a social justice activist for around 12 years. I come from a typical Burmese Buddhist military and civilian officials' family. I was raised in a military compound as a daughter of a captain After high school, I started exploring the outside world, and when I spoke up against military atrocities and failed leadership in ethnic and minority regions, most of my relatives and family members felt betrayed.

But I was inspired by the bravery and dedication of the pro-democracy movement in Myanmar and went on to unlearn what the military indoctrinated and relearn principles of human rights. And that made me one of their victims.

In 2012, I co-organized the first Myanmar Youth Forum in Myanmar and became the national coordinator for National Youth Congress while Myanmar was still under a quasi-military government. In 2014, before the parliament passed a bill that opposes women's reproductive rights, fake accounts reportedly created to target women activists shared personal information online, including mine. My phone number was shared on a range of pornographic sites, and I remember getting calls at midnight, asking what my price was. That was an attempt to shame the family and stop me from speaking out.

I kept organizing forums, community events, and protests for different issues and continued to be heavily attacked online and excluded from society.

After the coup in 2021, seven years after this first abuse, military propagandists doxxed me on multiple Telegram channels. My real name was shared with state media who used my social media profile picture and announced there was a warrant against me for speaking out against the military, asking people to let them know if they find me. Later, my family's address was posted on pro-military Telegram channels by military propagandists, asking police to check if I was there and if not, to intimidate my family members. My sister's social media profiles were also used to dox her. I managed to secure myself, my family and my sister but the harm on other women has continued.

I decided I needed to take some action, so for International Women's Day last year, I started the #TelegramHurtsWomen campaign on Twitter with my organization, Sisters2Sisters. We tagged Pavel Durov, (the founder of Telegram) on my posts, but are yet to get a response.

As recently as last month, my name was included in a list of more than 200 of the most-followed celebrities, bloggers, and activists (men and women) posted on a Telegram channel and threatened by pro-military groups, calling for people to check up on us and inform them if we are still speaking out.

---------

Credits:

Editors: Meera Senthilingam, Eliza Anyangwe and Hilary Whiteman

Illustrations: JC, for CNN

Design: Alicia Johnson

Data Editor: Carlotta Dotto

----------

How CNN conducted its analysis for this story

CNN commissioned a data scientist, whose identity is being withheld for safety reasons, to use AI software to scan content across the messaging platform Telegram.

The data scientist identified and analyzed public Telegram channels with stated allegiance to the military that were active between February 1, 2021 and December 31, 2022. They identified 198 such channels, and narrowed their analysis to focus on activity in the 10 channels with the greatest number of followers.

Separately, they developed a list of keywords used most commonly in conjunction with sexual content in Myanmar to identify 10 accounts with the greatest volume of sexual images and videos posted during this timeframe. They calculated the number of sexual messages, images and videos posted in these channels. All messages were checked manually to confirm the findings. The data scientist and CNN then analyzed the imagery posted in these 10 channels to calculate how many of them targeted women. A sample of 200 posts was checked and translated by CNN to identify if women were targeted for their political views.

CNN also analyzed activity on a public Telegram channel run by a well known pro-military social influencer. Within hours of forming, the number of followers on the channel reached thousands and within days it had more than 30,000 followers. CNN monitored the activity on this channel for five weeks in September 2022.

Editor's Note: Following the publication of this story, and reports by other media and NGOs, the UN released a statement from its experts calling for social media companies to stand up to the 'online campaign of terror' being run by Myanmar's military junta.

by Pallabi Munsi

CNN

9/8/23

(CNN) In the summer of 2021, Chomden was abroad, thousands of miles away from her home in Myanmar, when a friend sent her an urgent message informing her that an intimate video of her was being shared online.

When she saw the message, the 25-year-old said she froze "like a statue," her phone falling from her hand. She had just been doxxed.

A video of a naked Chomden -- whose name has been changed to protect her identity -- having sex with a former boyfriend, along with her name and Facebook profile picture, was circulating on a public channel on the messaging platform Telegram, and many of the group's approximately 10,000 followers had begun sending her abusive messages.

It had been just six months since Myanmar's civilian leader Aung San Suu Kyi was removed from power in a military coup led by General Min Aung Hlaing, who set up the State Administration Council (SAC) and now governs the country's caretaker government as an unelected prime minister.

Chomden had been on holiday at the time of the February 1 coup, and felt too scared to return home, but she says she had also felt obligated to speak out on social media about the plight of Myanmar's people and the junta's swift and brutal repression of critical voices, sharing video testimonies from people still in the country.

Far away from home, she had assumed she would be safe from any reprisals for her criticism of the ruling junta, but Chomden had not considered the possibility of online retribution.

Now, months after the coup, her once private video had been made public -- on a channel run by supporters of the military and used to circulate propaganda and dox people believed to oppose the SAC. Chomden's Facebook picture included a filter showing the flag of Myanmar's shadow government, the National Unity Government (NUG), identifying her as a supporter of the country's deposed, democratically elected government.

The accompanying text on the Telegram post, written in Burmese by the channel administrator, read: "The whore who is having sex with everyone and recording it in HD... Know your position, slut!"

She was also blackmailed by strangers claiming to have more videos of her, she says, and with no support system nearby, Chomden felt lost. The fallout from the post took such a toll on her mental health that she said: "I have to admit that I even thought of killing myself."

"They wanted to destroy my life," she told CNN.

Thousands of "politically active" women doxxed or abused

After the coup two years ago, as state repression intensified, civilians came together to defend towns and villages, and some rebel armies with a long history of conflict against the military united under the People's Defence Force (PDF), armed units aligned with the shadow government.

Fighting has since displaced hundreds of thousands of people and many now fear a deepening civil war.

But conflict in Myanmar is not only happening on the ground; attacks are prevalent online, and doxxing has emerged as a tool used extensively by supporters of the junta to threaten and silence people they see as their opponents.

Doxxing is the act of publicly identifying or publishing "private information about someone as a form of punishment or revenge" -- and men and women are being targeted in different ways.

When men are targeted, posts typically insinuate that they are linked to terrorist groups working to bring down the junta, multiple experts from NGOs and digital rights groups in the region told CNN. But when women are doxxed, the attacks frequently feature sexist hate speech, often coupled with explicit sexual imagery and video footage of them, as was Chomden's experience.

And in Myanmar, simply sharing the names and faces of people purported to support democracy can put those people at risk of arrest, while exposing private videos and photos subjects them and their entire families to societal shame.

Separate analyses by CNN and NGOs working in Myanmar shows this is all happening extensively on Telegram (which grew in importance after the military ordered Facebook to be temporarily blocked following the coup and has continued to block access since then), and activists are calling on the messaging company's Russian owners to take urgent action to stop this violence being perpetuated through their app.

A CNN analysis identified hundreds of sexual videos and images used in pro-military Telegram channels abusing women, often for having pro-democracy views, and hundreds more using sexual terms to achieve the same goal. A separate analysis by Myanmar Witness -- a project run by the UK-based Centre for Information Resilience that uses open-source tools to uncover human rights abuses -- in collaboration with grassroots organization Sisters2Sisters published recently looked at more than one million Telegram posts following the coup and found further evidence of this.

"We saw that (up to) 90% of the abusive posts were perpetrated by channels that appear to be pro-military and pro-SAC and ultra-nationalist groups ... targeted towards pro-democracy women," Me Me Khant, who led the Myanmar Witness research, told CNN.

A group of women hold torches as they protest against the military coup in Yangon, Myanmar July 14, 2021.

CNN commissioned a data science company with knowledge of Myanmar to analyze ten public pro-military Telegram channels active between the onset of the coup and the end of 2022, identified as containing among the greatest volume of sexual imagery and video footage. CNN is not naming the company because of concerns about their safety. More than 178,000 posts were shared in that timeframe, with one channel having more than 42,000 followers at the time of analysis.

Sexual messages were posted frequently (1,199 posts) and of these, sexually explicit images (204) and sexual videos (187) were common. Almost all of the images and videos (98%) targeted women, often using sexually explicit language in accompanying posts that criticized their pro-democracy views. Chomden's video was circulating in one of the channels analyzed -- almost six months after it was first posted elsewhere.

In a public Telegram channel monitored separately by CNN, misogyny was standard and the release of women's names and addresses commonplace. One post saw an administrator profusely insult a woman for supporting the pro-democracy movement, using offensive sexual language, and questioning her fertility. The post included the lines (originally in Burmese): "Because of her bad attitude, she could not get pregnant." Other posts released addresses calling for women to be found and arrested, or their homes and businesses closed down.

The recent Myanmar Witness report provided further evidence of this abuse online, targeting both prominent women and women in general. The team analyzed more than 1.6 million posts across 100 Telegram channels, which included channels identified as pro-military (64) and pro-democracy (36). Of the channels they observed, posts containing abusive terms targeting women increased eight-fold, from fewer than five posts per day on average in the first months after the February 2021 coup to more than 40 on average by July 2022, with more than 80 abusive posts on some days."

Myanmar's pro-regime accounts ramp up social media abuse

By last summer abusive Telegram posts against women have grown at least eight-fold, from fewer than five posts per day on average in the months that followed the February 2021 coup to more than 40 on average in July 2022. Channels supporting the State Administration Council (SAC) are responsible for 86% of them.

Daily posts containing abusive language targeting women, by Telegram channels' political affiliation.

Note: Myanmar Witness collected and analysed 1.6 million posts based on the activity of 100 Telegram channels between March 2021 and November 2022. Source: Myanmar Witness. Graphic: Carlotta Dotto

A further analysis of the content of the messages by the non-profit looked at the types of abuse and hate speech in 220 posts across Telegram, Facebook and Twitter (the majority on Telegram) and found that at least half of the posts were doxxing women in apparent retaliation for their political views or actions, the majority targeting women seen as pro-democracy. Of the doxxing posts analysed, 28% included an explicit call for the targeted women to be punished offline. The "overwhelming majority" of abusive posts came from male-presenting profiles supportive of Myanmar's military coup, targeting women who opposed the coup, the report states.

Myanmar Witness highlights in their report that the data gathered during their investigation is "highly likely" to represent just a small sample of politically motivated online abuse aimed at women. The same applies to the CNN analysis, meaning this likely shows just the tip of the iceberg, since the analyses were only of public channels and not private groups or messages.

Multiple experts expressed concern to CNN about links between these channels and the military, and the report goes on to suggest that some pro-military Telegram channels appear to be coordinating with the military itself, doxxing women who oppose it and seeming to make sure the junta is aware of private details that could be used to locate and arrest them. It highlights two cases of women being arrested shortly after being doxxed and of posts celebrating, or claiming credit for, their arrests.

"We've seen two high profile cases where two well-known women were arrested right after being doxxed. The channels also rejoiced after their arrests. When such things happen, you can't help but wonder: what if they weren't doxxed, would they still have been arrested — at the time?," Khant told CNN.

Wai Phyo Myint, Asia Pacific policy analyst at digital rights organization Access Now explains the wide range of significant offline consequences. "People [are] being arrested, blackmailed or forced into exile. Some have lost their livelihoods after their businesses and homes have been sealed off following the doxxing, others have had to go into hiding," she told CNN.

The Myanmar military did not respond to CNN's requests for comment.

Myanmar Witness did see some abuse and doxxing on Telegram channels identifying as pro-democracy, but to a much smaller degree. In response to this, Aung Myo Min, Minister of Human Rights for the National Unity Government acknowledged that gender inequality was a problem in the country. "Harassment based on gender or sexual orientation is very common in Myanmar, on both sides," Myo Min told CNN, adding that "it clearly shows the need (for) work, education and explanation needed on gender equality." But he also called on social media platforms to take action and create a better reporting system. "They have their part (in the) responsibilities," he said.

In a statement to CNN, Telegram spokesperson Remi Vaughn reiterated the Terms of Service and wrote: "Telegram is a platform for free speech. However, sharing private information (doxxing) and calling for violence are explicitly forbidden by our Terms of Service."

CNN was unable to identify clear rules on doxxing in the platform's Terms of Service but did see that the promoting of violence and sharing of illegal pornographic content on "publicly viewable Telegram channels, bots, etc" was prohibited. The platform also provides an email -- abuse@telegram.org -- to report this content.

When CNN followed up with Telegram regarding rules of doxxing -- or the lack thereof -- on their publicly available Terms of Service they did not respond.

Sexual violence as a "targeted weapon"

The Global Justice Center, an international human rights and humanitarian law organization working to advance gender equality, produced a report in 2015 that describes gender stereotypes as pervasive in Myanmar and supported by religious, cultural, political, and traditional practices.

"Women in Burma are generally understood to be secondary to men," the report stated, and in the eight years since its publication, little has changed, believes Akila Radhakrishnan, president of the Global Justice Center.

She believes the mainstream view of women in Myanmar continues to be one of them "being quiet, being docile," and of their bodies seen "as a public collateral," and, in her opinion, the attacks on women in pro-military Telegram groups mirror what the military itself would do.

"The Myanmar military has, for decades, used sexual and gender-based violence as a targeted weapon," Radhakrishnan told CNN. "Women and women's bodies are really viewed in a very narrow mindset by the military, and that reflects on the acts that they perpetrate against women, whether that is physical violence, whether that is other types of violence, the latest being the use of technology."

But women have long played a role in the country's pro-democracy movement, once led by ousted leader Aung San Suu Kyi, who won the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991 for her commitment to the cause. Following the coup, women have been pivotal in organizing pro-democracy protests and experts believe doxxing attacks began and progressively got worse as more women joined these protests.

Anti-coup protesters march in Yangon, Myanmar on March 8, 2022 to mark International Women's Day.

"A woman who is shamed for her body, a woman who is shamed for sexual activities, that means that that woman does not have value within the society anymore," Radhakrishnan said.

After she was doxxed, Chomden told CNN that it was only a matter of hours before she began to be sexually harassed and bullied online. The messages came pouring in, first from strangers abusing her, then, she said, from friends appalled by her "shameful" behavior as word spread across the community.

Chomden said that her mother, still a resident in Myanmar, bore the brunt of the attack: she didn't leave her house for three months out of fear of being shamed and ostracized by people who'd seen or heard about the video.

Chomden continues to support the NUG, but feels scared to return home after the coup, especially since the military had issued an arrest warrant against her for her activism in April 2021, but the video made the idea even more terrifying: "How could I ... with so much shame?," she told CNN.

Getting women to 'censor themselves'

Victoire Rio, a digital rights activist working in Myanmar believes that doxxing is part of a larger strategy to get people to "censor themselves".

"If I should put a timeline to this," Rio told CNN, "you will see that immediately after the coup, the military were going after anybody that had the potential to rally people: that's influencers, movie stars, key activists, sort of local influential figures."

Rio explained that this was done by charging them under penal code 505 for speaking out against the military, which according to Human Rights Watch, was amended to punish a broader range of critics of the coup and the military. But "that wasn't really effective," Rio said.

So, in the summer of 2021, Rio believes there was a change of strategy. "That's when you start seeing doxxing, abuse and targeting extending beyond influential figures, but really starting to target anyone and everyone," said Rio. "It is a campaign of terror [and] a very effective strategy to try to push self-censorship and really try to scare people into silence."

While this cannot be directly linked to the military, the activity is clear in public Telegram channels led by military supporters. Digital rights activist Htaike Htaike Aung, believes the use of sexually explicit content to silence critics has worked. As a result of all the doxxing that has happened, she told CNN: "We see more and more women and gender minorities getting afraid to voice their opinions."

Left no choice but to leave

Linn -- CNN is not using her full name out of concern for her safety -- is a social activist who has been vocal about human rights violations and women's rights in Myanmar since 2017.

She was arrested on March 3, 2021, she told CNN, for organizing non-violent demonstrations following the coup and was held at Insein Prison in Yangon for eight months.

Soon after her release, the 34-year-old, began to speak out about the treatment of incarcerated people in Insein. (A 2021 Human Rights Watch report describes "dehumanizing" experiences of Myanmar prisons, including "sexual violence and other forms of gendered harassment and humiliation from police and military officials" since the coup.)

"I spoke out about violence and human rights abuses in prison on social media and to news media agencies" Linn said. "I also talked and campaigned to strengthen public participation in the revolution."

The military officials who are responsible for Insein prison did not respond to CNN's request for comment.

A week after her release, Linn was targeted on a popular pro-military Telegram channel which at the time had over 18,000 followers. Sharing screenshots of her Facebook posts detailing what she said was going on inside Insein, as well as pictures of her with deposed leader Suu Kyi, her doxxer wrote: "She was released not longer than 2 weeks ago, and she is again doing the same thing. She might want to go back inside." Others in the group soon responded with more gendered abuse.

CNN was able to see the abusive posts and the conversation that followed. One user wrote: "Kill her!". Another: "After everyone has f**ked her, deliver her verdict," followed by several more expressing similar sentiments. More posts followed.

She was released not longer than 2 weeks ago, and she is again doing the same thing. She might want to go back inside (prison)Kill her!If you treat her with care you can use at least 10 years. Keep it safe in Insein. (prison)After every has f**ked her, deliver her verdict.That chick has tattoos, and she is just f**k chick for dog PDFs from jungle.

Linn had sought refuge at her organization's safe house (which CNN is not naming out of concern for their safety) following her prison release but after being doxxed, it became harder and harder for her to venture outside. "Military supporters and religious extremists started keeping watch in the neighborhoods I was likely to be in," she said.

She told CNN that she was determined not to feel ashamed but was worried about the safety of others. "I knew if I were re-arrested, others living in the safe house would also be targeted."

In March 2022, a year after her ordeal began, Linn snuck out of the safe house and began her journey out of Myanmar. "I did not care if I was re-arrested, I didn't want anyone else to get arrested because of me."

So far from Telegram, little platform accountability

The activity on these Telegram channels can be reported to the platform's moderators and some channels have been taken down as a result. Telegram took down a channel CNN shared soon after it was highlighted, as well as channels highlighted in a recent report by the BBC. But CNN saw that when channels are blocked, new ones soon pop up, and experts highlighted that many harmful ones are never removed.

In January 2022, a digital civil rights organization working in the region (which CNN is not naming to ensure the safety of their teams) listed 14 public Telegram channels that were violating the "human rights of people of Myanmar" in various ways, including the posting of sexually explicit imagery and videos of women without their consent, all launched by a pro-military social influencer who runs multiple channels on Telegram.

The organization say they sent the document -- seen by CNN -- to Telegram, expressing concern that this was happening on its platform, along with a few case studies, calling on Telegram to adhere to UN human rights principles, they told CNN. But one year later, they say they are yet to get a response and say the abuse is continuing to happen in large volumes.

Myint of Access Now highlights that while Telegram has now taken down many channels run by these pro-military influencers, other channels are still running by the same name. "Why is Telegram not being more proactive so as to not let (people with) the same name open more and more channels?,"

Telegram's statement to CNN claimed doxxing, the posting of sexual content and the perpetuation of violence is a violation of its Terms of Service. It also added: "Our moderators use a combination of proactive moderation and user reports to remove such content from our platform. This clear policy has allowed pro-democracy movements around the world to organize large-scale movements safely using our platform, for example in Hong Kong, Belarus and Iran.

But Rio believes Telegram has not played this role in Myanmar. "Telegram claims to be such a revolutionary platform helping Iranians, (and) Hong Kongers but when it comes to Myanmar, it fails to recognize how the platform is abused," she said.

Telegram did not respond to CNN's specific questions on whether it moderates Burmese language content or why abusive, doxxing and pornographic posts on public channels continue despite the platform's Terms of Service.

"We've seen zero efforts from Telegram to reach out to civil society in Myanmar and try to understand what actually is happening," concluded Rio. They need to actually "engage and get a sense for what the risks associated with their platforms are and develop mechanisms to be in a better position to address risks that emerge."

Telegram did not respond to CNN's follow-up request for comment on why it was allegedly not responding to emails and memos from digital rights activists working in Myanmar and showing evidence of large scale doxxing.

Chomden, who felt her life fall apart after being doxxed on one of Myanmar's many pro-military Telegram channels, stresses the need for urgency, saying: "It's not just me, hundreds of women in Myanmar are going through the same and it's not okay. Telegram needs to know it's not alright... to let these groups ruin people's lives."

--------

Hear the testimonies of other women doxxed by pro-military groups

Dr Yin (CNN is not using her full name out of concern for her safety)

Age: 28

Profession: Doctor

Her account has been edited for clarity and brevity

Right after the coup on February 1, 2021, I teamed up with other doctor friends to treat civilians injured during the protests that had erupted. We were determined to treat people in need and within two days, we were running free medical clinics. We also gave reports on the numbers injured -- and killed -- to reporters in the city.

In mid-March, a reporter friend warned me that the military had issued an arrest warrant in my name under Penal Code 505 (A), which had been recently amended and now covered more people speaking critically about the coup and the military. So, I took a bag and fled the country.

After I left, someone I knew posted a video of me along with false information claiming I was having an affair and an even bigger nightmare began.

Pro-military groups had somehow obtained the video, and pictures from my Facebook profile ended up on several Telegram channels run by pro-military groups and the images exposed my location.

Many people started sending rude messages to me, and back home, my mother was humiliated by people in her community who commented that I have a bad character. On my blog, people started commenting that I should be punished for going against Burmese culture (which frowns upon couples living together out of wedlock and on women having affairs).

It all took a massive toll on my life. I no longer use social media because I am so scared. I can't go home, and I do not have any protection where I am because there is an arrest warrant out for me in Myanmar. I am now an illegal immigrant. I feel so hopeless and there is no solution in sight.

***

Thinzar Shunlei Yi

Age: 34

Profession: Pro-democracy activist for Sisters2Sisters

Her account has been edited for clarity and brevity

I have been a social justice activist for around 12 years. I come from a typical Burmese Buddhist military and civilian officials' family. I was raised in a military compound as a daughter of a captain After high school, I started exploring the outside world, and when I spoke up against military atrocities and failed leadership in ethnic and minority regions, most of my relatives and family members felt betrayed.

But I was inspired by the bravery and dedication of the pro-democracy movement in Myanmar and went on to unlearn what the military indoctrinated and relearn principles of human rights. And that made me one of their victims.

In 2012, I co-organized the first Myanmar Youth Forum in Myanmar and became the national coordinator for National Youth Congress while Myanmar was still under a quasi-military government. In 2014, before the parliament passed a bill that opposes women's reproductive rights, fake accounts reportedly created to target women activists shared personal information online, including mine. My phone number was shared on a range of pornographic sites, and I remember getting calls at midnight, asking what my price was. That was an attempt to shame the family and stop me from speaking out.

I kept organizing forums, community events, and protests for different issues and continued to be heavily attacked online and excluded from society.

After the coup in 2021, seven years after this first abuse, military propagandists doxxed me on multiple Telegram channels. My real name was shared with state media who used my social media profile picture and announced there was a warrant against me for speaking out against the military, asking people to let them know if they find me. Later, my family's address was posted on pro-military Telegram channels by military propagandists, asking police to check if I was there and if not, to intimidate my family members. My sister's social media profiles were also used to dox her. I managed to secure myself, my family and my sister but the harm on other women has continued.

I decided I needed to take some action, so for International Women's Day last year, I started the #TelegramHurtsWomen campaign on Twitter with my organization, Sisters2Sisters. We tagged Pavel Durov, (the founder of Telegram) on my posts, but are yet to get a response.

As recently as last month, my name was included in a list of more than 200 of the most-followed celebrities, bloggers, and activists (men and women) posted on a Telegram channel and threatened by pro-military groups, calling for people to check up on us and inform them if we are still speaking out.

---------

Credits:

Editors: Meera Senthilingam, Eliza Anyangwe and Hilary Whiteman

Illustrations: JC, for CNN

Design: Alicia Johnson

Data Editor: Carlotta Dotto

----------

How CNN conducted its analysis for this story

CNN commissioned a data scientist, whose identity is being withheld for safety reasons, to use AI software to scan content across the messaging platform Telegram.

The data scientist identified and analyzed public Telegram channels with stated allegiance to the military that were active between February 1, 2021 and December 31, 2022. They identified 198 such channels, and narrowed their analysis to focus on activity in the 10 channels with the greatest number of followers.

Separately, they developed a list of keywords used most commonly in conjunction with sexual content in Myanmar to identify 10 accounts with the greatest volume of sexual images and videos posted during this timeframe. They calculated the number of sexual messages, images and videos posted in these channels. All messages were checked manually to confirm the findings. The data scientist and CNN then analyzed the imagery posted in these 10 channels to calculate how many of them targeted women. A sample of 200 posts was checked and translated by CNN to identify if women were targeted for their political views.