Mysteries of the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor

by Ronnie Pontiac

August 15, 2013

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Sexuality defines spirituality and visa versa, from the celibacy of Catholic priests and the strict rules of evangelical Christian marriages to transgressive tantric intercourse deliberately breaking taboos, human beings have struggled in vain to find a dependable universal formula for balancing sex and religion. The men and women of the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor, a not-so-secret secret society, believed they had found that universal formula. But there was much more to their program of education than instructions for lovers. In the Hermetic Brotherhood Luxor we glimpse how these secret societies occurred, assisting and undermining each other, sometimes simultaneously. We also see how the roots of American Metaphysical Religion directly impacted our culture. Max Theon, for example, had little to do with America, yet through the H.B. of L. his influence on American Metaphysical Religion was profound.

MYSTERIOUS ORIGINS OF THE H.B. of L.

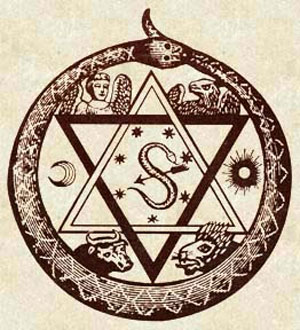

The Magician tarot card anticipated by an alchemical emblem of Hermes Trismegistus?

How do we explain the profusion of Hermetic groups at the end of the 19th century? First the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor, then Anna Kingsford’s Hermetic Society in 1884, the legendary Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn in London in1888, and in the American Midwest the Hermetic Brotherhood of Light in 1895.

A practical occult order that taught the use of the magic mirror for scrying, the H.B. of L. promised initiates that they would learn how to communicate with secret and even discarnate masters by means of astral travel. Theirs was not a mere correspondence course by U.S. mail; students would receive astral instruction as well. Why not disembodied masters, when mediums were wowing the nation with channeled spirits speaking from beyond the grave?

According to the order itself the H.B. of L. dated all the way back to the ancient Egyptian city of Luxor, and further still, to the primal City of Light, the heaven of archetypes. Yet the order admitted that its most recent incarnation began in Egypt in 1870.

What do we make of Kenneth Mackenzie’s claim that he was in contact with six adepts of the Hermetic Brotherhood of Egypt before 1874? Of course, the H.B. of E. may have had nothing to do with the H.B. of L. Mackenzie isn’t a reliable scholar, though his Royal Cyclopedia of Freemasonry is a feast for the eyes and filled with interesting information and misinformation.

Mackenzie began his literary career in his teens by translating authors as diverse as Herodotus and Hans Christian Andersen but his mentor the astrologer and Rosicrucian enthusiast Frederick Hockley damned him with faint praise, “I have the utmost reluctance even to refer to Mr. Kenneth Mackenzie. I made his acquaintance about 15 or 16 years since. I found him then a very young man who having been educated in Germany possessed a thorough knowledge of German and French and his translations having been highly praised by the press, exceedingly desirous of investigating the Occult Sciences, and when sober one of the most companionable persons I ever met.”

Apparently Mackenzie was a mean drunk who relished unleashing his eloquence in criticism. Nevertheless at age twenty he was appointed a Member of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and a Fellow of the Society of Antiquaries of London. Seven years later Mackenzie traveled to Paris in 1861 to meet with the French magus Eliphas Levi.

Mackenzie was instrumental in the founding of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn. In fact, the cipher manuscripts that were offered as proof of the Hermetic Golden Dawn’s mission having been approved by Anna Sprengel and the German Rosicrucians are in his handwriting.

Then there’s Rene Guenon’s inexplicably confident remark about the H.B. of L. springing from the Rosicrucians, after Blavatsky emphatically denied any connection between the two orders.

In 1875 Blavatsky claimed contact with a Brotherhood of Luxor, masters of the magical arts. Olcott, her compatriot in the adventure that was the Theosophical Society, believed they were also training him, and described one materializing in his room. This was no mere astral projection, the initiate left behind his keffiyeh (head cloth), which Olcott cherished.

Did the Theosophical Society find its doctrine of secret masters in the teachings of the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor? Blavatsky later condemned the H.B. of L. for swindling gullible truth seekers. But Blavatsky had good reason to discredit competitors who had seriously eroded her following in America. Theosophists who felt somewhat abandoned when Blavatsky and Company took leave of America never to return swelled the ranks of the H.B. of L. So much so that Blavatsky felt compelled to temporarily reverse her prohibition against practical occultism. For a select elite she added lessons in astral travel and other occult practices to the Theosophical curriculum. But the elite Esoteric Section didn’t last long.

Members of the Theosophical Society had to rely on Blavatsky and her invisible masters for their miracles and communications, with dim hope of achieving such communication for themselves. But the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor offered practical lessons in achieving access to such wisdom.

As for the H.B. of L.’s opinion of Blavatsky, they thought she had fallen under the spell of Buddhist masters, initiates of a lower order of enlightenment, nihilists who believed nothing personal survives the death of the body.

Perhaps one of the strangest things about the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor is its lack of Egyptian content. As Geoffrey McVey wrote in his essay Thebes, Luxor, and Loudsville, Georgia: The Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor and the landscapes of 19th-century Occultisms, “It is significant that, beyond the attachment to Luxor and the occasional reference to Isis, there is nothing especially Egyptian about the teachings and practices of the H.B. of L.; its primary sources include [author of The Magus Francis] Barrett, the French occultist Eliphas Levi, Bulwer-Lytton’s Zanoni, Rosicrucianism, and the work of Paschal Beverly Randolph. There are no “Egyptian rites,” no emphasis on hieroglyphics, and, in fact, very little mention of Egypt at all.”

Whereas we have rich documentation of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, the H.B. of L. remains a confusing collection of mysteries. Yet behind these mysteries were people history has not entirely forgotten.

THE ENIGMA OF PASCHAL BEVERLY RANDOLPH

Paschal Beverly Randolph’s mother died not long after he was born; he was homeless as a child. The son of a Virginian farmer and his slave and therefore biracial he was accepted by no community. He grew up impoverished in New York City doing menial labor; he worked, for example, as a bootblack. Still a teen he took jobs on ships so he could travel. He visited Europe and the Near East, learning from every metaphysical master he could find. The story has been told that Eliphas Levi initiated him in Paris, but we have no proof that they met, and Randolph certainly did not reflect Levi’s insistence on the magical importance of a quiet life. In France, Randolph was introduced not only to mesmerism, magic mirrors, and the occult doctrines of Europe, but also the importance of hashish in clairvoyance.

In his 20s Randolph became a well-known trance medium, and like many spiritualists of the day his lectures denounced slavery and supported abolition. In 1853 he helped recruit black soldiers for the Union Army. After emancipation Randolph lived in New Orleans where he taught newly freed slaves how to read and write. Randolph took training in medicine and maintained a practice of one sort or another most of his life. He fought for birth control when even mentioning it meant risking arrest. The author of a shelf full of books on health, sexuality, channeling and the occult, he ran his own independent publishing company. He wrote two novels, making him one of the first African American novelists published.

Randolph’s Rosicrucian apologists have spread stories about his membership in a secret society of initiates that included Abraham Lincoln. General Ethan Allen Hitchcock is supposed to have introduced Randolph to Lincoln. Randolph is said to have been on the Lincoln memorial train on the way to Springfield, but allegedly he was kicked off the train because he was the only black man aboard, a strange event given that the nation was mourning the Great Emancipator. But these appear to be folk tales rather than facts.

When Randolph returned to London in the 1870s he might have initiated Burgoyne and Davidson, who would become the leaders of the H.B. of L. in America. Some have suggested he initiated H.B. of L. founder Max Theon, and others that Max Theon initiated him. Burgoyne and Davidson certainly took some of the content of the H.B. of L. from Randolph’s works, especially the materials on sex magic, though they took pains to distance themselves from him, alleging that he had fallen into black magic by using sex magic for material ends, but that was a gross oversimplification of the very complicated life of a man who publicly and enthusiastically endorsed sex, drugs and the occult before Aleister Crowley was born.

Randolph had a knack for alienating his admirers. A popular spiritualist, Randolph then denounced the principles of spiritualism losing their support. When his work for abolition and then for the freed slaves earned him the respect of average Christians in the communities he worked with he alienated them by declaring in a lecture that God is electricity, motion and light, not Jesus. Later in life he would complain bitterly about his abandonment by the Theosophists, the spiritualists, the abolitionists and even his Hermetic brethren, often blaming his rejection on his race; he didn’t seem to understand his own penchant for burning bridges. Without him the H.B. of L. would have been of an entirely different character, yet his involvement seems to have been minimal, and his rejection by Burgoyne and Davidson final.

Some have argued that Paschal Beverly Randolph when he visited France and Great Britain in the 1860s on his way to Greece, Constantinople, Palestine, and Egypt was initiated into the Rosicrucians by Hargrave Jennings. Mackenzie allegedly initiated Jennings. While Mackenzie and Jennings were wonderful writers their theories were considered questionable long before modern scholarship. Most likely this so-called Rosicrucian order was more DIY than supernatural.

Was Randolph the first to make practical application of the sacred phallus theories that had been enchanting western esoteric historians of the late 19th century?

Was Randolph a Rosicrucian, initiated in the 1850s in Germany, as suggested by another Rosicrucian popularizer R. Swinburne Clymer, Supreme Grand Master of the Fraternitas Rosae Crucis? Clymer is notorious for suspect scholarship and his assertion seems unlikely given Randolph’s own statement: “I studied Rosicrucianism, found it suggestive, and loved its mysticism. So I called myself The Rosicrucian, and gave my thought to the world as Rosicrucian thought and lo, the world greeted with loud applause what it supposed had its origin and birth elsewhere than in the soul of P.B. Randolph. Very nearly all that I have given as Rosicrucianism originated in my own soul….” Randolph goes on to explain that being half black he found himself and his ideas ignored by the metaphysical community of the day, but the same ideas once labeled Rosicrucian were successful, and allowed him to overcome the racial prejudice of his peers.

Blavatsky engaged in a lifelong rivalry and alleged magical battle with him. She supposedly sensed the moment of his suicide and made a cryptic comment about his murderous mental attack on her bouncing back on him. She used the n word when she talked about him.

Randolph agreed with the H.B. of L. that sex magic should only be practiced by married couples, and he had just as many warnings about the dire consequences of abusing it, but for Randolph sex magic had many more uses than procreation. As Hugh B. Urban wrote: “Randolph not only reflects, but in fact epitomizes and exaggerates these claims about the tremendous power and potential evils of sex. Indeed, he developed his own “science” of sexual magic, in which the moment of orgasm becomes the ultimate spiritual power with the potential to attain virtually any desired end, from health and longevity to mystical insights.”

But Randolph’s personal life failed to reflect his beliefs. He became notorious when accused of arranging so called mystical rites where white women could enjoy dalliances with black men. He found monogamy difficult. At first, because he could not resist the temptations in his path, then because of his terrible jealousy and fear that his young wife would abandon him.

Randolph’s death, like his life, was full of contradictions. Fifty years old, married to a girl not yet twenty, father of a newly born son he named Osiris Buddha (who would grow up to become a respected physician) this champion of women’s rights and spiritual love had become a depressed alcoholic. Did he shoot himself in the head standing on the sidewalk one morning? The neighbor woman who claimed he came to her house and committed suicide right in front of her wrote that while sober he was a sweet man but drunk he was angry, jealous and grief stricken. He had been desperate to raise money, offering to sell the rights to all his books, offering to sell his medical practice, deeply bitter that those who had borrowed freely from his work seemed to be flourishing while he was becoming ever more obscure and poor. But true believers insisted that he was actually murdered by someone who confessed to the crime on their deathbed.

EMMA HARDINGE BRITTEN AND GHOSTLAND

Emma Floyd was born in London, England in 1823. As child she astonished people by predicting events that later occurred, and by relaying information from dead dear ones, people she had never even heard of. As a pianist she amused herself by playing songs people were about to request. When her father perished her childhood ended. She helped provide for her family, giving music lessons and finding work as an actress.

Emma wrote: “When quite young, in fact, before I became acquainted with certain parties who sought me out and professed a desire to observe the somnambulistic tendencies for which I was then remarkable. I found my new associates to be ladies and gentlemen, mostly persons of noble rank, and during a period of several years, I, and many other young persons, assisted at their sessions in the quality of somnambulists, or mesmeric subjects…it was one of their leading regulations never to permit the existence of the society to be known or the members thereof named.” Emma called them the Orphic Circle, but the participants probably had no name for what was more focused social gathering than organized secret society.

Groundbreaking research by Marc Demarest based on work by Mathiesen suggests that the Orphic Circle may have been based on a social circle of occult fellowship and spiritualist experimentation that included popular occult authors Lord Bulwer-Lytton, “Zadkiel” and “Raphael,” expert on Rosicrucianism Frederick Hockley, and Richard F. Burton, perhaps most famous as the translator of the uncensored One Thousand and One Nights. Another member of the circle, Damarest points out, may have kept Emma as a mistress. Philip Henry Stanhope, an Earl, is most remembered for his involvement in the Kaspar Hauser scandal. But he may be the “baffled sensualist” who took advantage of her as a girl that she never names in her autobiography.

Among the luminaries was Charles Dickens. In her next career as an actress, Emma worked with the great novelist and later referred to him as “my old friend.” Another friend of Dickens, Hargrave Jennings the Rosicrucian enthusiast managed the Covent Garden company where Emma got her first extant acting credit. Demarest wonders if Jennings was the unnamed fiancée Emma mentioned many years later in her autobiography. They certainly shared the same interests.

From 1838 to 1855 Emma worked as an actress. She never played the starring roles, but in her teens she was promoted as a beauty. When she visited America she did get a leading role in a play on Broadway. She began to write plays. Some may have made it to the stage, but she never had a success.

In February 1856 Emma claimed that the spirit of a sailor from a ship called the Pacific communicated with her after the vessel was lost at sea. She began visiting mediums. With the Spiritualists Emma found a new life. She worked as chorale director for spiritualists in New York, an editor for the Christian Spiritualist, and she was tested for ten months as an aspiring medium. In 1857 she began delivering lectures while in trance.

The following summer the important spiritualist journal The Banner of Light published a biographical note about Emma and by the end of the year she was lecturing from the Atlantic to the Mississippi, from Portland Maine to New Orleans, so in demand she had to be booked months in advance. European spiritualist writers took notice.

In 1859 Emma worked to establish The Home for Outcast Women in several cities including Boston and New York. Though some of the leading citizens of Boston were on board the plan failed.

Her lecture circuit now took her to California and Nevada; she even visited mining towns. In a mining town in Nevada Mark Twain saw her and wrote home about it. This remarkable woman traveled alone, unheard of in those times.

In 1864, during Lincoln’s bid for reelection, Emma’s skills as a lecturer rallied support for the president on a 32-city tour. Her speech a year later, the day after Lincoln’s assassination, was shared far and wide, and praised by journalists as her finest work.

One of the founding members of the Theosophical Society, Emma disapproved of what it became, especially disparaging its appeal to the authority of invisible masters. Emma was the most popular author among the early Theosophists. When she published Modern American Spiritualism: A Twenty Years’ Record of the Communion Between Earth and the World of Spirits in 1870 she became a renowned expert on the phenomena. The book looks at the history of Spiritualism in America by state and region.

In 1870 she married her husband William. Together they would navigate not only her career as a writer and lecturer but also their own collaboration as healers using “electro-cranial” therapy.

Emma’s book Art Magic or Mundane sub-mundane and super-mundane spiritism (1876), published a year before Blavatsky’s classic Isis Unveiled, covered “Pre-existence of the Soul – Its Descent into Matter,” “Extracts from the Vedas,” “The History of the Sun God,” “Hindoo, Egyptian, Greek and Roman Theology,” “Sex Worship,” “How Solar and Sex Worship came to be Interblended,” “Jewish Cabala,” “Spiritism and Magic,” “The Rosicrucians,” “Astral Light,” “Woman as Priestess and Sibyl,” “Narcotics,” Thibetian Lama,” “Magic Amongst the Mongolians,” “The Great Pyramid – Its Probable Use,” “The Modes of Divination, both lawful and unlawful, amongst the Jews,” “Siberian Schaman,” “Salamanders – Sylphs – Gnomes – Fairies,” “Witchcraft,” “Alchemists – Rosicrucians – Philosopher’s Stone,” and included chapters on Nostradamus, Agrippa, Swedenborg, Mesmer, and Paracelsus, crystal seeing, stones, charms, amulets, talismans, clairvoyance and magic mirrors. It also lifted its illustrations from The Rosicrucians by Hargrave Jennings.

The similar but more extensive encyclopedic surveys of esoteric tradition written by Blavatsky and later by Manly P. Hall, and the practical lessons of the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor, the Hermetic Society of the Golden Dawn, and the O.T.O., all found a prototype in Emma’s work.

Emma and her husband spent1878 and 1879, as Spiritualist missionaries in Australia and New Zealand.

The National Spiritualist Association of Churches in the United States and the Spiritualists’ National Union in the United Kingdom still use her bullet points. Among these tenets was a belief in “The Continuous Existence of the Human Soul.” When Blavatsky guided the Theosophical Society into an area of Buddhism without belief in personal survival, Emma, joining many other American Theosophists, turned away and gave her support to the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor.

Returning to England, Emma at age 58 began a tireless lecture circuit. Within a year, worn down by work and travel, she developed a chronic sore throat, retreating to a friend’s house in Paris for rest and recuperation. Yet lecture tours remained her principle activity well into her sixties.

In 1894 Emma published Nineteenth Century Miracles. Despite her efforts, which included more advertising than she had ever used before, the sales weren’t enough to improve her life. It didn’t help that the press ignored her despite the great popularity she had once enjoyed. So she decided to return to America. Her three-year absence had made the press as disinterested in her in America as they had been in England. Yet she drew a crowd of perhaps ten thousand to her summer lecture in Lake Pleasant, New York. But the following May she announced her return to England, where she resumed a brutal schedule of lecture tours into 1887. She lectured on a variety of subjects, including her experiences in New Zealand illustrated with “limelight views of the people and country before and after the volcanic eruption.”

Late in the fall of 1887 Emma as editor issued the first number of The Two Worlds, a journal of spiritualism and the occult. The journal helped to unite the burgeoning spiritualist movement and gave an outlet to young writers who later became influential, among them A.E Waite. Emma didn’t shy away from using the journal to promote herself. She published her own novellas in The Two Worlds.

But The Two Worlds ended in financial scandal and lawsuits. Emma devoted herself to “a fine new magazine” The Unseen Universe. Now she had no collaborators, except her sister, a librarian. Despite more novellas The Unseen Universe only lasted a year, leaving dangling chapters of unfinished books.

In 1892 Emma released the second volume of Ghostland, and a novel The Mystery of No. 9 Stanhope Street. The book’s heroine suffers betrayals, the first by her mother who rents her out as a model to a lecherous artist named Stanhope. Was this fiction really confession? Nearing the end of her life did she feel compelled to record what the Earl had really done to her? Yet the character of Stanhope instead closely resembles another Stanhope entirely, the painter of a famous nude Temptation of Eve. While we have no evidence of a relationship or even contact between Stanhope the painter and Emma, could she have been his model and mistress, or was this an elaborate ploy to avoid the appearance of an open accusation against Stanhope the Earl? Perhaps the more poignant detail is that almost age seventy Emma still wrote and self promoted to survive.

With the failure of the Unseen Universe, Emma turns to autobiography. Seeking not only the money she needed to survive, but also hoping to secure her place in the historical record. In 1894 her husband William died. Strangely, Emma wrote more about the parrot William had given her than about her husband of 24 years.

The first wave of Spiritualism was dying down as the ideal of an international movement faded. Emma planned an Encyclopedia of Spiritualism. In 1898 The Progressive Thinker republished Art Magic and Ghost Land, but Emma didn’t receive any benefit from the reprints.

In 1900 The Autobiography of Emma Hardinge was published, but she did not live to see it. Her sister the librarian had to edit it for publication and the narrative ends with William’s death.

ROBERT FRYAR: CRYSTAL AWARE

John Dee’s obsidian magic mirror

Robert Fryar had a bookstore in the city of Bath. If you wanted to see manuscripts of key writing by Paschal Beverly Randolph in Great Britain, Fryar was your man. He published a notorious series titled Esoteric Physiology that included tantric concepts later found in the teachings of the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor.

His shop must have been a treat. You could find not just a priceless manuscript on the art of using crystal mirrors to contact spirits and other entities; you could buy a magic mirror. For Emma Hardinge Britten’s magazine, The Two Worlds, Fryar wrote “The History and Mystery of the Magic Crystal.”

Like so many others in the mirror scrying lineage, Fryar worked with a seer, his wife, whom he referred to humbly as “The British Seeress.” Before the H.B. of L. He had promoted her in the spiritualist journals.

Fryar published the Bath Occult Reprint series. One of the books in that series, The Divine Pymander of Hermes Mercurius Trismegistus, from the text of Dr. Everard, Ed. 1650 (1884), contained the first notice of the existence of the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor.

“TO WHOM IT MAY CONCERN, Students of the Occult Science, searchers after truth and Theosophists who may have been disappointed in their expectations of Sublime Wisdom being freely dispensed by the HINDOO MATHATMAS, are cordially invited to send in their names to the Editor of this Work, when, if found suitable, can be admitted, after a short probationary term, as members of an Occult Brotherhood, who do not boast of their knowledge or attainments, but teach freely and without reserve all they find worthy to receive. N.B. All communications should be addressed “Theosi” c/o Robt. H. Fryar, Bath. CORRECTION. “Correspondents” will please read and address “Theosi” as “THEON.”

This printed erratum can be taken as mysterious or a bit comical. At least no one feared being mistaken for an infallible authority.

Inquiring novices received a return letter asking for a photograph and a horoscope. For a small fee a horoscope could be provided for those without one. Those who made it into the Brotherhood, and not everyone did, received mail order lessons and a mentor by way of pen pal. The name of the order printed on a slip of paper was burned after reading.

But after only two years Fryar became disillusioned. He claimed that the leaders of the H.B. of L. had cheated him. The Theosophical Society’s journal Lucifer published Fryar’s complaint, even naming the H.B. of L.’s leaders:

“For the purpose of correcting any prejudicial suspicion or erroneous misrepresentation of myself, arising from the insertion of the note at the end of the “Bath Occult Reprint Edition” of the “Divine Pymander” as associated with Society of the H.B. of L. known to me only through the names of Peter Davidson and T.H. Burgoyne, alias D’Alton, Dalton, etc, and the supposed adept to be a Hindu of questionable antecedents,” I wish it be understood I have no confidence, sympathy or connection therewith, direct or indirect…”

So ended Fryar’s brief but important sojourn with the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor.

MAX THEON: AMBIGUOUS LEADER

Max Theon (the name he took means supreme god or perhaps god is supreme) was the son of a Warsaw rabbi. His name may have been Maximilian Louis Bimstein, and he may have been born in 1850. His father may have been a leader of the Frankist reformation among the Jews of Warsaw. The Frankists, concerned with sacred sexuality, became notorious for orgiastic rites where ecstasy was a sacrament.

Max traveled the world to learn from Arabic, Hindu and Jewish masters but Max’s first initiation may have been as a Zoharist, an erotically ecstatic sect of Chassidic Jews from whom he seems to have received important ideas about the cabala and about the integration of sexuality and spirituality.

Recent scholarship argues that Max’s teachings never deviated far from Jewish eschatology, especially Lurianic Tikkun

In 1873, Carl Kellner, a colleague of Paschal Beverly Randolph, met a young man in Cairo known as Aia Aziz. Later Aziz changed his name to Max Theon. Was Max also a student of Blavatsky’s first occult master, Paolos Metamon, the Coptic magus allegedly associated with the Hermetic Brotherhood of Light?

Max’s most famous student, Mirra, better known as The Mother, the colleague of the legendary Sri Aurobindo, and co-creator of Integral Yoga, claimed that Blavatsky had been Max’s student. Were Blavatsky and her colleague Olcott early members of the H.B. of L.? .

In his book Visions of the Eternal Present, Max wrote: “In 1870 (and not in 1884, as the Theosophists claimed), an adept of calm, of the ever-existing ancient Order of the H. B. of L., after having received the consent of his fellow-initiates, decided to choose in Great Britain a neophyte who would answer his designs. He landed in Great Britain in 1873. There he discovered a neophyte who satisfied his requirements and he gradually instructed him. Later, the actual neophyte received permission to establish the Exterior Circle of the H. B. of L.” Theon was the initiate; his neophyte was Peter Davidson, a student of Hargrave Jennings.

But newspapers in London warned of a disreputable psychic healer named Theosi, perhaps explaining the printed correction of the name as Theon in the first notice of the H.B. of L. printed in the back of Fryar’s reprint of the Pymander. The address given for the healer matches the address Max Theon later gave in his marriage certificate.

The Ancient and Noble Order of H. B. of L. had a charter signed: “M. Theon, Grand Master pro temp of the Exterior Circle.” The charter proclaimed:

“We recognize the eternal existence of the Great Cause of Light, the invisible center whose vibrating soul, gloriously radiant, is the living breath, the vital principle of all that exists and will ever exist. It is from this divine summit that goes forth the invisible Power which binds the vast universe in an harmonious whole.”

“We teach that from this incomprehensible center of Divinity emanate sparks of the eternal Spirit, which, after accomplishing their orbit, the great cycle of Necessity, constitute the sole immortal element of the human soul. Accepting thus the universal brotherhood of humanity, we reject, nevertheless, the doctrine of universal quality.”

“We have no personal preferences and no one makes progress in “the Order” without having accomplished his assigned task thereby indicating aptitude for more advanced initiation.”

“Remember, we teach freely, without reservation, anyone worthy of instruction.”

“The Order devotes its energies and resources to discover and apply the hidden laws and active forces in all fields of nature, and to subjugate them to the higher will of the human soul, whose power and attributes our Order strives to develop, in order to build up the immortal individuality so that the complete spirit can say I AM.”

“The members engage themselves, to the best of their ability, in a life of moral purity and brotherly love, abstaining from the use of intoxicants except for medicinal purposes, working for the progress of all social reforms beneficial for humanity.”

“Finally, the members have full freedom of thought and judgment. By no means may one member be disrespectful towards members of other religious beliefs or impose his own convictions on others.”

“Each member of our ancient and noble Order has to maintain, human dignity by living as an example of purity, justice and goodwill. No matter what the circumstances may be, one can become a living center of goodness, radiating virtue, nobility and truth.”

Then everything changed for Max when in 1885 he married the young Irish poet he called Alma. Mary Ware was a formidable Scottish medium and lecturer on the occult, as well as founder of the Universal Philosophical Society, all before she met him. She became his seeress and soon he lost interest in the H. B. of L. though under his guidance a branch in Paris flourished after the demise of the lodges in America. Max and Alma ultimately settled in Algeria.

Alma trance channeled much of the content of their teachings and of their periodical The Cosmic Review. They attracted supporters from all over the world. Max took students as he saw fit, he didn’t follow the H.B. of L. protocol and while Davidson and others continued to seek out his advice about the order Max does not appear to have been active, although when the American branch collapsed he was the one who ordered the lodges closed.

In the tradition of the alchemical soror or sister, Max and Alma worked together as teachers, writers, and initiators. They called their new order the Movement Cosmic. In some ways their activity was much like that of Betty and Stewart White: a female provided insight into the workings of the universe, engaging occult sources of knowledge. Betty’s well-developed theories about the afterlife required her to explain the unobstructed to the obstructed. Alma explored astral dimensions in search of extraordinary information.

But in 1908, after 23 years of marriage, Alma died. Max became deeply depressed. He stopped publication of their journal The Cosmic Review, and ended the Movement Cosmique. Then he suffered terrible injuries in a car accident. World War 1 completed Max’s misery. He lived until 1927, allegedly known among the Algerian locals as a reclusive miracle worker, helpful whenever possible but he never organized another spiritual mission.

PETER DAVIDSON: MASTER OF THE MISTLETOE

Davidson is an important but somewhat ignored contributor not only to the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor, but also to the O.T.O. and to American Metaphysical Religion. A violinmaker born near Findhorn, Scotland he wrote a popular handbook about violins, which in its last reprinting he stuffed with occult lore unrelated to the instrument.

By the 1870s Davidson was already interested in contacting guardian spirits with magic mirrors and he claimed to be in touch with a Tibetan adept. A student then colleague of Hargrave Jennings, Davidson found his mission when he met Max Theon.

Charged with guiding the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor’s efforts in America, Davidson and alias Burgoyne arrived in late spring 1886. Dalton was already using the pen name Zanoni. Peter Davidson wrote under the pen name Mejnor, Zanoni’s spiritual mentor in Bulwer Lytton’s novel Zanoni.

H.B. of L. had planned a community, or colony as they called it, in California, announced in Burgoyne’s lengthy letter in the monthly journal he edited The Occult Magazine When they realized they would not be able to find support for such an expensive project they focused on Florida, but finally settled on Georgia where the colony was founded, but it became more of a family compound than an active intentional community and agricultural commune. Isolated in the rural American south, his network of pen pals nevertheless made him one of the prime intelligencers of his time

There, on a gasoline-powered printing press he imported, Davidson published two periodicals, Mountain Musings, a daring progressive series of publications for locals, and The Morning Star, more traditional and Christian friendly, for the benefit of a wider international audience. As far as Davidson was concerned both publications served the same ideals as the Hermetic Brotherhood of Luxor, but cloaked in more accessible metaphors.

Davidson was renowned for his herbal formulas. Like John Winthrop Jr. he cooked up an elixir prized in the area. He was also considered the best moonshiner around. He wrote a book that indicated extensive experience with making and using various drugs including a concoction of mistletoe he said could purify the mind and harmonize body and soul. Good ginseng hunters could always find work with him. The elixir of life he distributed would have been recognized by Randolph before him and by Crowley after.

Davidson is probably the source of the Celtic, Druidic, and Irish influences in some of the teaching of the H.B. of L. But the writings of Godfrey Higgins and Blavatsky herself diluted the authority of Druid tradition, theorizing that it came from Buddhist missionaries, rather than being an authentic western tradition.

In his monograph Vital Christianity, Peter Davidson made these remarks based on Revelations 2:17: “The inward and true Self, the Dual-Soul-Germ, the ‘I am,’ is identical with the Christ, and the nature of such is the great Mystery and final secret which God holds in reserve for those who seek and love Him. ‘To him that overcometh will I give to eat of the hidden manna, and will give him a white stone, and the stone a new name written, which no man knoweth saving that he receiveth it.’”

The prolific Davidson authored A Homeopathic Pharmacopoeia, Masonic Mysteries Unveiled, The Mistletoe and Its Philosophy, The Book of Light and Life, Scintillations from the Orient, Fragments of Freemasonry, Elementals, and The Laws of Magic Mirrors, and more books and articles, though little of his writing is available online or in print.

Davidson was an early champion of what we now call holistic medicine and a sharp critic of physicians who preferred drastic procedures to herbal and other more subtle therapies.

Davidson also made magic mirrors. His advertisement in the Occult Magazine stipulates that that the mirrors have the required paranaphthaline treated surface. What was paranaphthaline?

In On the Heights Himalay (1896) by A. Van Der Naillen, an occult romance of undependable scholarship, in a ritual presided over by a Brahman, paranaphthaline is a black gum that turns pink when charged with subtle energy by a very young couple dancing erotically publicly just before the consummation marriage. The scene may have been inspired by an earlier book, Fraser’s Twelve Years in India, which included a description of an erotic ritual used by a community to charge paranaphthaline gum for use in a magic mirror. Fraser claimed he accurately saw distant and future events in the charged mirror. The passage was important to Paschal Beverly Randolph who quoted it in his book Eulis. Davidson later reprinted Fraser’s account in The Theosophist.

Though his work appeared in The Theosophist, Blavatsky warned Olcott to be careful of Davidson.