by Benjamin Mazar

Encyclopedia.com

Accessed: 11/27/22

(1) An oasis on the western shore of the Dead Sea and one of the most important archaeological sites in the Judean Desert. En-Gedi (En-Gaddi in Greek and Latin; ʿAyn Jiddī in Arabic) is actually the name of the perennial spring which flows from a height of 656ft. (200 m.) above the Dead Sea. In the Bible, the wasteland near the spring where David sought refuge from Saul is called "the wilderness of En-Gedi" and the enclosed camps at the top of the mountains, the "strong-holds of En-Gedi" (i Sam. 24:1–2). En-Gedi is also mentioned among the cities of the tribe of Judah in the Judean Desert (Josh. 15:62). A later biblical source (ii Chron. 20:2) identifies En-Gedi with Hazazon-Tamar but this is rejected by most scholars. In the Song of Songs 1:14 the beloved is compared to "a cluster of henna in the vineyards of En-Gedi"; the "fishers" of En-Gedi are mentioned in Ezekiel 47:10.

In later literary sources, Josephus speaks of En-Gedi as the capital of a Judean toparchy and tells of its destruction during the Jewish War (Wars, 3:55; 4:402). From documents found in the "Cave of the Letters" in Naḥal Ḥever, it appears that in the period before the Bar Kokhba War (132–135), the Jewish village of En-Gedi was imperial property and Roman garrison troops were stationed there. But in the time of Bar Kokhba, it was under his control, and was one of his military and administrative centers (see *Judean Desert Caves). In the Roman-Byzantine period, the settlement of En-Gedi is mentioned by the Church Fathers; Eusebius describes it as a very large Jewish village (Onom. 86:18). En-Gedi was then famous for its fine dates and rare spices, and for its balsam.

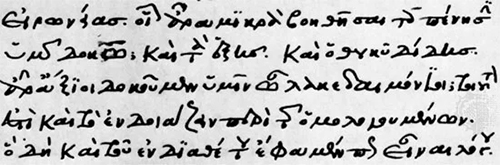

Eusebius of Caesarea (c. 260/265 – 30 May 339), also known as Eusebius Pamphilus, was a Greek historian of Christianity, exegete, and Christian polemicist. In about AD 314 he became the bishop of Caesarea Maritima in the Roman province of Syria Palaestina. Together with Pamphilus, he was a scholar of the biblical canon and is regarded as one of the most learned Christians during late antiquity. He wrote Demonstrations of the Gospel, Preparations for the Gospel and On Discrepancies between the Gospels, studies of the biblical text. As "Father of Church History" (not to be confused with the title of Church Father), he produced the Ecclesiastical History, On the Life of Pamphilus, the Chronicle and On the Martyrs. He also produced a biographical work on Constantine the Great, the first Christian Roman emperor, who was augustus between AD 306 and AD 337.

Although Eusebius' works are regarded as giving insight into the history of the early church, he was not without prejudice, especially in regard to the Jews, for while "Eusebius indeed blames the Jews for the crucifixion of Jesus, he nevertheless also states that forgiveness can be granted even for this sin and that the Jews can receive salvation." Some scholars question the accuracy of Eusebius' works. For example, at least one scholar, Lynn Cohick, dissents from the majority view that Eusebius is correct in identifying the Melito of Peri Pascha with the Quartodeciman bishop of Sardis. Cohick claims as support for her position that "Eusebius is a notoriously unreliable historian, and so anything he reports should be critically scrutinized." Eusebius' Life of Constantine, which he wrote as a eulogy shortly after the emperor's death in AD 337, is "often maligned for perceived factual errors, deemed by some so hopelessly flawed that it cannot be the work of Eusebius at all." Others attribute this perceived flaw in this particular work as an effort at creating an overly idealistic hagiography, calling him a "Constantinian flunky" since, as a trusted adviser to Constantine, it would be politically expedient for him to present Constantine in the best light possible.

-- Eusebius, by Wikipedia

After surveys of the area, five seasons of excavations were conducted at En-Gedi by B. Mazar, T. Dothan, and I. Dunayevsky between the years 1961–62 and 1964–65. The settlement of En-Gedi was found to have been established only in the seventh century b.c.e. with no evidence of occupation in the time of David (tenth century b.c.e.). Excavations showed that Tell Goren (Tell el-Jurn), a small hill above the southwestern part of the plain near Naḥal Arugot, was one of the main centers in the oasis beginning with the Israelite and especially in the Iron ii, Hellenistic, and Roman-Byzantine periods. Surveys of the area revealed that the inhabitants of En-Gedi had developed an efficient irrigation system and engaged in intensive agriculture. The combination of abundant water and warm climate made it possible for them to cultivate the palm trees and balsam plants for which En-Gedi was renowned. The settlement was apparently administered by a central authority which was responsible for building terraces, aqueducts, and reservoirs, as well as a network of strongholds and watchtowers along the road linking En-Gedi with Teqoa.

Five periods of occupation were uncovered on Tell Goren. The earliest settlement, Stratum v, was a flourishing town which had spread down the slopes of the tell dating from the Judean kingdom (c. 630–582 b.c.e.). Various installations, especially a series of large clay "barrels" fixed in the ground, together with pottery, metal tools, and ovens indicated that workshops had been set up for some special industry. This discovery conforms with various literary sources (Josephus and others) which mention En-Gedi as a center for the production of opobalsamon ("balsam"). It can thus be assumed that En-Gedi was a royal estate which ran this costly industry in the service of the king. This first settlement was apparently destroyed and burned by Nebuchadnezzar in 582/1 b.c.e.

The next town on the tell (Stratum iv) belongs to the Persian period (fifth–fourth centuries b.c.e.). Its area was more extensive than the Israelite one and its buildings were larger and well-built. A very large house, part of it two-storied, which contained 23 rooms, was found on the northern slope of the tell. En-Gedi at this time was part of the province of Judah as attested by the many sherds inscribed "Yehud," the official name of the province.

Stratum iii belongs to the Hasmonean period. Its famous dates are mentioned in this period by Ben Sira (Ecclus. 24:14). En-Gedi flourished, especially at the time of Alexander *Yannai and his successors (103–37 b.c.e.). A large fortress on the tell was probably destroyed in the period of the Parthian invasion and the last war of the Hasmoneans against Herod.

The next occupation (Stratum ii) contains a strong fortress on the top of the tell surrounded by a thick stone wall with a rectangular tower. This settlement is attributed to the time of Herod's successors (4–68 c.e.); it was destroyed and burned apparently during the Jewish War in 68 c.e. Coins from the "Year Two" of the war were found in the area of the conflagration.

During the Roman-Byzantine period (Stratum i) the inhabitants of the tell lived in temporary structures and cultivated the slopes of the hill (third–fifth centuries c.e.). It appears that at least from the time of the Herodian period the main settlement at En-Gedi moved down to the plain, east and northeast of Tell Goren between Nahal David and Nahal Arugot.

A Roman bath was found in the center of this plain about 660 ft. (200 m.) west of the shore of the Dead Sea. It is dated by finds, especially six bronze coins, to the period between the fall of the Second Temple and the Bar Kokhba War.

A sacred enclosure from the Chalcolithic period was found on a terrace above the spring. It consists of a group of stone structures of a very high architectural standard. The main building was apparently a temple which served as the central sanctuary for the inhabitants of the region.

Excavations (1970) brought to light the remains of a Jewish settlement dating from the Byzantine period. The synagogue had a beautiful mosaic floor depicting peacocks eating grapes, and the words "Peace on Israel," as well as a unique inscription consisting of 18 lines which, inter alia, calls down a curse on "anyone causing a controversy between a man and his fellows or who (says) slanders his friends before the gentiles or steals the property of his friends, or anyone revealing the secret of the town to the gentiles. …" (According to Lieberman, it was designed against those revealing the secrets of the balsam industry.) A seven branched menorah of bronze and more than 5,000 coins (found in the synagogue's cash box by the ark) were also uncovered.

[Benjamin Mazar]

Since the writing of the entry above by Benjamin Mazar, new archaeological work and historical studies concerning En-Gedi have been made. En-Gedi is an oasis on the fringe of the Judean Desert, situated in the middle of the western shore of the Dead Sea, in the rift valley, the lowest place on earth. The climate of the rift valley is arid and climatic changes have in the past influenced the flow of the springs as well as the levels of the Dead Sea. The source of the springs is in the aquifer of the Judaean Group of the Cenoman-Touron Formation. In the past, there were ten springs, but only four are active today: 'Arugot, David, En-Gedi, and Shulamit.

En-Gedi is mentioned for the first time in the Bible as Hazazon Tamar (Gen. 14:7), which was identified as En-Gedi (ii Chron. 20: 2). In i Samuel 23:29; 24:2–3, David took refuge in the wilderness of En-Gedi. En-Gedi is mentioned once in each of the Talmudic writings (tj, Shevi'it 9:2, 38d; tb, Shabbat 26a). The inhabitants of En-Gedi made their living from agriculture. They cultivated a very poor marl and stony soil with irrigation channels from the waters of the springs. They also collected salt and asphalt (bitumen) from the shores of the Dead Sea, as well as chunks of sulfur from the marl plains for the production of medicines. The main cultivations in this oasis were palm trees and barley; balsam, a cash crop, was also grown in the region. Writers from the Roman period praised the excellent dates that grew in En-Gedi and Judaea (Pliny, Hist. Nat. 13:6, 26; Josephus, Ant., 9: 7). The palm tree, a symbol of Judaea, was used as a motif on Jewish coins and Flavian victory coins. Transportation between En-Gedi and other parts of the country was dictated by geographical and political conditions. During ancient times En-Gedi had a strong connection with Jerusalem. During the First Temple period, En-Gedi was first established as a military outpost on the western shores of the Dead Sea over against Moab and Edom. Later maritime transportation was undertaken on the Dead Sea, as has been proven by the discovery of wooden and stone anchors, as well as of anchorages near En-Gedi and at other locations around the Dead Sea. Although sailing vessels have not yet been found underwater, drawings and graffiti of sailing ships are known from Masada and on the mosaic map of Madaba. The connection between En-Gedi and Nabataea, and later with Arabia, is attested by ancient historians, on the one hand, as well as in the Judean Desert Documents, on the other. Nabatean coins have also been found in archaeological excavations.

During the 1980s–90s a systematic archaeological survey was conducted in the area, and a number of intact burials of the Second Temple period were revealed and excavated. These were family tombs and the bodies were wrapped with linen shrouds and interred in wooden coffins, usually without funerary objects (Hadas, 1994). In the late 1990s a large area of the Byzantine village adjacent to the synagogue was excavated and many dwellings were revealed, all of which supports Eusebius' description of En-Gedi as "a large village of Jews" (Hirschfeld, in press). During this project the irrigated agricultural systems were also investigated and excavated (Hadas, 2002). In recent years (2003–5), a new suburb of En-Gedi dating from the Second Temple period has been revealed to the northwest of the synagogue (Hadas, forthcoming). Caves in the cliffs behind En-Gedi have also been surveyed, revealing Bar-Kochba coins and papyri in some of them, and much earlier Persian period ornaments in another. Additional excavations conducted in the area of the synagogue area (Hadas, in press) have shown that the Byzantine village was destroyed and burnt in the sixth century c.e. This was the end of the Jewish settlement, which had existed here almost continuously for about one thousand years. A gap in the occupation of En-Gedi existed until the 13th–14th centuries c.e., when a Mamluke village was founded at the spot and existed there for about a century. Remains of this period were found above the synagogue site and in the general vicinity. A water mill was also built at this time (Hadas, 2001–2) and it still exists near the En-Gedi spring. En-Gedi remained in ruins until the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948.

[Gideon Hadas (2nd ed.)]

(2) Settlement in the Judean Desert on the west bank of the Dead Sea, founded by Israeli-born youth first as a *Naḥal military outpost in 1953 and later in 1956 as a civilian kibbutz affiliated to the Ihud ha-Kevuẓot ve-ha-Kibbutzim. Its primary functions were, initially, those of defense; but it also successfully developed farming methods adapted to the local conditions of a hot desert climate and an abundance of fresh water from the En-Gedi Springs. These are fed by an underground flow (from the rain-rich intake area on the western slopes of the Hebron Hills), which emerges on a fault line. An area surrounding the Springs has been declared a nature reserve because of the small enclave of Sudano-Deccanian flora existing there. A field school of the Society for the Preservation of Nature, a youth hostel (Bet Sara), and a recreation home are all situated there. Until 1967 the means of transportation to En-Gedi were by land or sea from Sodom, on the south side of the Dead Sea. In 1962 a narrow asphalt road was built and it replaced the 50 km. dirt road that was frequently destroyed by flash floods in the winter months. At that time there was a motorboat that sailed from Sodom to En-Gedi, and a medical doctor used to arrive once a week by light plane (Piper) from Beer Sheva. In 1971 an asphalt road was built northwards and connected En-Gedi to Jerusalem, shortening the travel time from En-Gedi to Tel Aviv, from 5 to 2 hours. The kibbutz economy was based mainly on tourism, including a guest house and medicinal waters. Farming was based on mango plantations, date palms, and herbs. The kibbutz had a 25-acre botanical garden with 900 plant species from all over the world. In 2002 the population of En-Gedi was 603.

[Efraim Orni / Shaked Gilboa and Gideon Hadas (2nd ed.)]

_______________

Bibliography:

B. Mazar et al., En-Gedi, Ḥafirot … (1963); B. Mazar, in: bies, 30 (1966), 183ff.; idem, in: Archaeology, 16 (1963), 99ff.; idem, in: Archaeology and Old Testament Study, ed. by D. Winton Thomas (1967), 223ff.; idem, in: iej, 14 (1964), 121–30; 17 (1967), 133–43; Y. Aharoni, in: Atiqot, 5 (1961–62), En-Gedi; ibid., 3 (1961), 148–62; idem, in: iej, 12 (1962), 186–99; B. Mazar, S. Lieberman, and E.E. Urbach, in: Tarbiz, 40 (Oct. 1970), 18–30. add. bibliography: G. Hadas, "Stone Anchors," in: Atiqot, 21 (1992), 55–57; idem, "Nine Tombs," in: Atiqot, 24 (Hebrew; 1994); idem, "Water Mills," in: baias, 19–20 (2001–2), 71–93; idem, "Ancient Irrigation Agriculture in the Oasis of Ein Gedi" (Doctoral Thesis, 2002); idem, "Excavations by the Synagogue," in: Atiqot, 49 (in press); G. Hadas et al., "Two Ancient Wooden Anchors," in: jna, 34:2 (2005), 307–15; Y. Hirschfeld, Excavations (forthcoming).

*************************

En-Gedi Scroll

by Wikipedia

Accessed: 11/26/22

https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/201 ... /90786164/ and https://www2.cs.uky.edu/dri/the-scroll-from-en-gedi/ [FOR PIX]

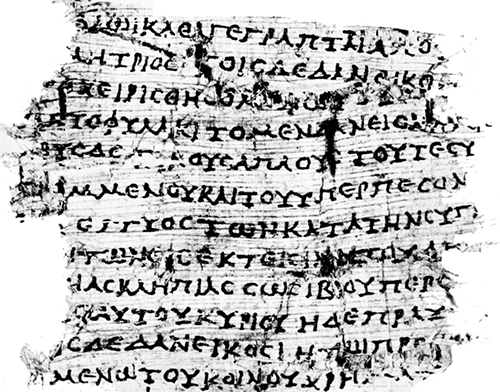

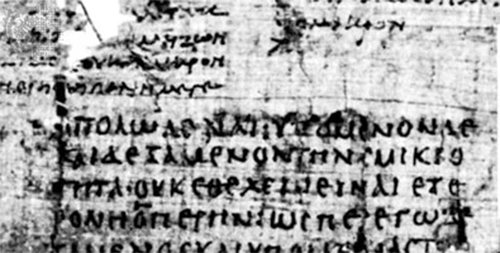

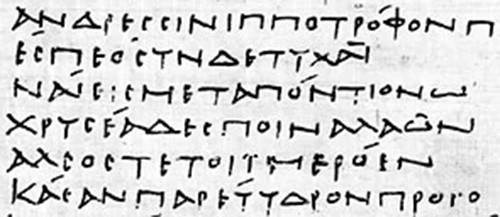

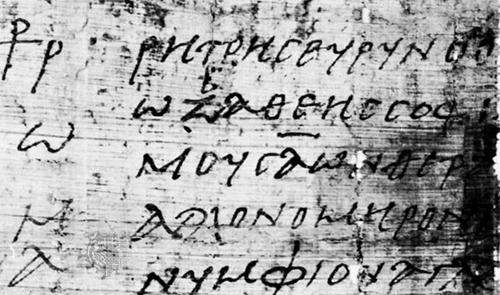

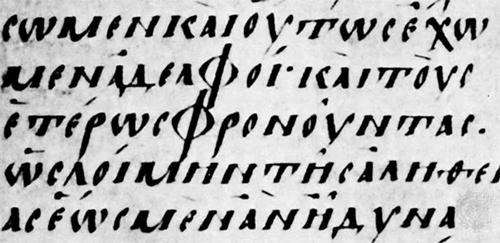

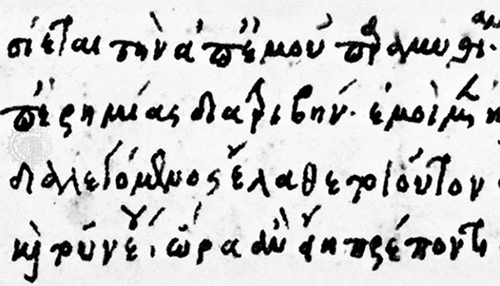

A section of the ancient scroll from Ein Gedi

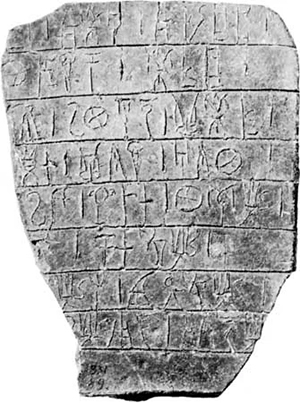

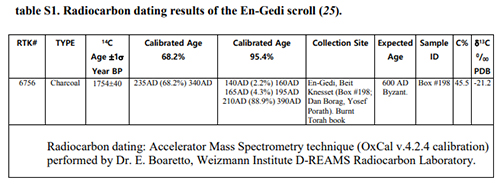

The En-Gedi Scroll is an ancient Hebrew parchment found in 1970 at Ein Gedi, Israel. Radiocarbon testing dates the scroll to the third or fourth century CE (210-390 CE), although paleographical considerations suggest that the scrolls may date back to the first or second century CE.[1][2]

The first problem he hoped to solve was how to detect ink hidden inside rolled-up scrolls. From the late third century A.D. onward, ink tended to include iron, which is dense and easy to spot in X-ray images. But the papyri found at Herculaneum, created before A.D. 79, were written with ink made primarily of charcoal mixed with water, which is extremely difficult to distinguish from the carbonized papyrus it sits on.

-- Buried by the Ash of Vesuvius, These Scrolls Are Being Read for the First Time in Millennia: A revolutionary American scientist is using subatomic physics to decipher 2,000-year-old texts from the early days of Western civilization, by Jo Marchant, Photographs by Henrik Knudsen

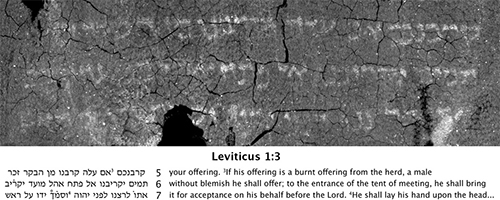

This scroll was discovered to contain a portion of the biblical Book of Leviticus, making it the earliest copy of a Pentateuchal book ever found in a Holy Ark.[citation needed] The deciphered text fragment is identical to what was to become, during the Middle Ages, the standard text of the Hebrew Bible, known as the Masoretic Text, which it precedes by several centuries, and constitutes the earliest evidence of this authoritative text version. Damaged by a fire in approximately 600 CE, the scroll is badly charred and fragmented and required noninvasive scientific and computational techniques to virtually unwrap and read, which was completed in 2015 by a team led by Prof. Seales of the University of Kentucky.[3]

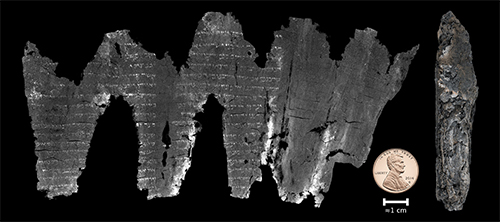

Discovery

The En-Gedi Scroll was discovered in a 1970 excavation headed by Dan Barag and Ehud Netzer of the Institute of Archaeology at Hebrew University, and Yosef Porath of the Israel Antiquities Authority at the ancient synagogue in Ein Gedi in Israel,[4] the site of an ancient Jewish community. It was found in the burned remains of a Torah Ark in the ruins of the ancient synagogue at Ein Gedi.[5] Severely damaged by a fire around 600 CE, the scroll appeared as burned, crushed chunks of charcoal. Each disturbance caused the scroll to disintegrate, leaving few options for conservation or restoration. The scroll fragments were preserved by the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), although for decades after their discovery the scrolls remained in storage due to their severely damaged condition.[6]

Text

According to radiocarbon testing performed by the Israel Antiquities Authority, the scroll has a probability of 88.9% of dating to 210-390 CE and 68.2% of dating to 235-340 CE.[1] The scroll was written at Ein Gedi where there was a community of Essenes,[7][8][9] the Jewish sect made famous for their probable association with the Dead Sea Scrolls.

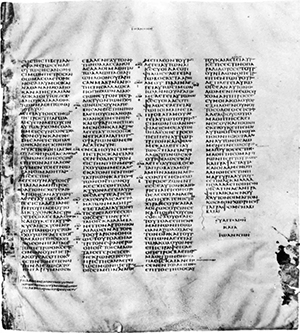

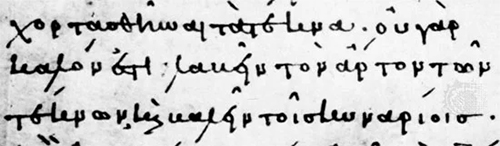

The text deciphered so far consists of 18 complete lines and 17 partial lines of the first two chapters of Leviticus. The text is identical to the medieval era Masoretic Text,[10] unlike the Dead Sea scrolls which have variations from the Masoretic.[11] Michael Segal of the Hebrew University of Jerusalem described the scroll as being the earliest evidence of the exact form of the Masoretic Text.[12]

Recovery

The ancient scroll was discovered in 1970 but was in such fragile state it disintegrated on touch and so was unable to be studied.[11][6] This led scientists to search for non-traditional techniques to reconstruct the text of the document virtually. This search led to the development of a virtual unwrapping technique developed by Prof. Seales of the University of Kentucky, which allowed scientists to virtually reveal the text contained in the En-Gedi scroll in 2015.[6]

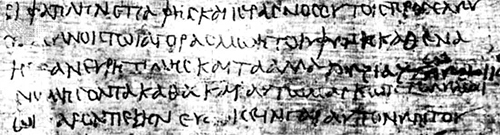

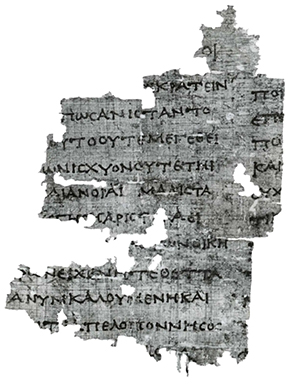

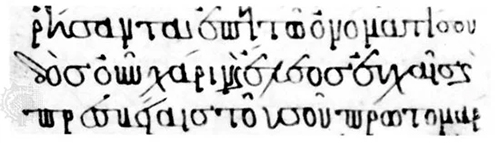

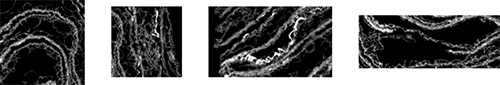

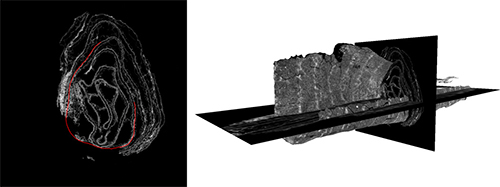

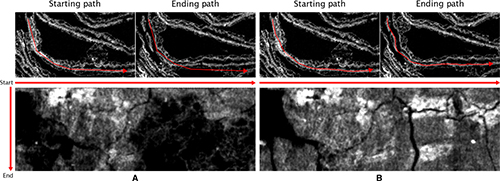

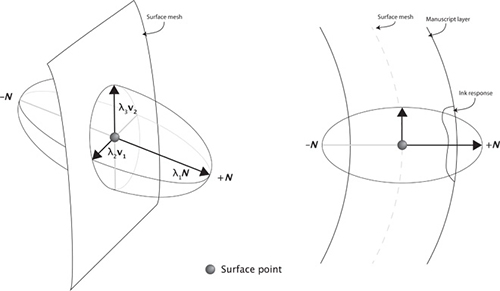

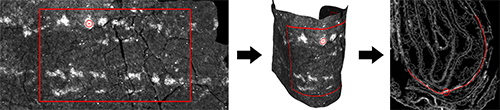

The virtual unwrapping process begins with using X-ray microtomography (micro-CT) to scan the damaged scroll. This scan is non-invasive and uses the same technology as a traditional CT scan. In this scan, researchers used a high energy x-ray beam to pass through the depth of the scroll. Each material in the scroll will absorb the x-ray radiation differently, where the scroll will absorb this radiation minimally but more than the empty space around it, and the ink will absorb this radiation significantly more than the scroll around it.[6][13] This creates the sharp contrast we see between the text and the scroll in the final images of the virtually unwrapped scroll. When the scroll completes a full rotation with respect to the x-ray source, the computer generates a 2D slice of the cross-section, and performing this iteratively allows the computer to build up a 3D volumetric scan describing the density as a function of the position inside the scroll. The only data needed for the virtual unwrapping process is this volumetric scan, so after this point the scroll was safely returned to its protective archive. The density distribution is stored by the computer with corresponding positions, called voxels or volume-pixels.[6] The goal of the virtual unwrapping process is to determine the layered structure of the scroll and try to peel back each layer while keeping track of which voxel is being peeled and what density it corresponds to. By transforming the voxels from a 3D volumetric scan to a 2D image, the writing on this inside is revealed to the viewer. This process happens in three steps: segmentation, texturing and flattening.

Segmentation

The first stage of the virtual unwrapping process, segmentation, involves identifying geometric models for the structures within the virtual scan of the scroll. Because of the extensive damage, the parchment has become deformed and no longer has a clearly cylindrical geometry. Instead, some portions may look planar, some conical, some triangular, etc.[14] Therefore, the most efficient way to assign a geometry to the layer is to do so in a piecewise fashion. Rather than modeling the complex geometry of the entire layer of the scroll, the piecewise model breaks each layer into more regular shapes that are easy to work with. This makes it easy to virtually lift off each piece of the layer one at a time. Because each voxel is ordered, peeling off each layer will preserve the continuity of the scroll structure.[6]

Texturing

The second stage, texturing, focuses on identifying intensity values that correspond with each voxel using texture mapping. From the micro-CT scan, each voxel has an associated brightness value that corresponds to a higher density. Since the metallic ink is denser than the carbon-based parchment, the ink will appear bright compared to the paper. After virtually peeling off the layers during the segmentation process, the texturing step matches the voxels of each geometric piece to their corresponding brightness value so that an observer is able to see the text written on each piece. In ideal cases, the scanned volume will match perfectly with the surface of each geometric piece and yield perfectly rendered text, but there are often small errors in the segmentation process that generate noise in the texturing process.[6] Because of this, the texturing process usually includes nearest-neighbor interpolation texture filtering to reduce the noise and sharpen the lettering.

Flattening

After segmentation and texturing, each piece of the virtually deconstructed scroll is ordered and has its corresponding text visualized on its surface. This is, in practice, enough to read the inside of the scroll, but for the arts and antiquities world, it is often best to convert this to a 2D flat image to demonstrate what the scrolls parchment would have looked like if they could physically unravel without damage. This requires the virtual unwrapping process to include a step that converts the curved 3D geometric pieces into flat 2D planes. To do so, the virtual unwrapping models the points on the surface of each 3D piece as masses connected by springs where the springs will come to rest only when the 3D pieces are perfectly flat. This technique is inspired by the mass-spring systems traditionally used to model deformation.[6]

After segmenting, textualizing, and flattening the scroll to obtain 2D text fragments, the last step is a merge step meant to reconcile each individual segment to visualize the unwrapped parchment as a whole. This involves two parts: texture merging and mesh merging.

Texture Merging

Texture merging aligns the textures from each segment to create a composite. This process is fast and gives feedback on the quality of the segmentation and alignment of each piece. While this is good enough to create a basic image of what the scroll looks like, there are some distortions which arise because each segment is individually flattened. Therefore, this is the first step in the merging process, used to check if the segmentation, texturing, and flattening processes were done correctly, but does not produce a final result.[6]

Mesh Merging

Mesh merging is more precise and is the final step in visualizing the unwrapped scroll. This type of merging recombines each point on the surface of each segment with the corresponding point on its neighbor segment to remove the distortions due to individual flattening. This step also re-flattens and re-textures the image to create the final visualization of the unwrapped scroll, and is computationally expensive compared to the texture merging process detailed above.

Using each of these steps, the computer is able to transform the voxels from the 3D volumetric scan and their corresponding density brightnesses to a 2D virtually unwrapped image of the text inside.[6]

See also

Herculaneum papyri

References

1. "En-Gedi Scroll Finally Deciphered - Archaeology, Technologies - Sci-News.com".

2. A. Yardeni in M. Segal, E. Tov, W. B. Seales, C. S. Parker, P. Shor, Y. Porat, An Early Leviticus Scroll from En Gedi: Preliminary Publication, Textus 26, 2016.

3. de Lazaro, Enrico (September 23, 2016). "En-Gedi Scroll Finally Deciphered". Sci News.

4. Harder, Whitney (September 22, 2016). "The scroll from En-Gedi: A high-tech recovery mission". Sci News.

5. Watts, James W (2017). Understanding the Pentateuch as a Scripture. John Wiley & Sons. p. 77. ISBN 9781405196383.

6. Seales, W. B.; Parker, C. S.; Segal, M.; Tov, E.; Shor, P.; Porath, Y. (2016). "From damage to discovery via virtual unwrapping: Reading the scroll from En-Gedi". Science Advances. 2 (9): e1601247. Bibcode:2016SciA....2E1247S. doi:10.1126/sciadv.1601247. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 5031465. PMID 27679821.

7. Pliny the Elder. Historia Naturalis. V, 17 or 29

8. Josephus. The Jewish War. p. 2.119.

9. Josephus (c. 75). The Wars of the Jews. 2.119.

10. Geggel, Laura (September 21, 2016). "1,700-Year-Old Dead Sea Scroll 'Virtually Unwrapped,' Revealing Text". Live Science.

11. Wade, Nicholas (21 September 2016). "Modern Technology Unlocks Secrets of a Damaged Biblical Scroll". The New York Times.

12. "En-Gedi: Ancient scrolls 'virtually' deciphered to reveal earliest Old Testament scripture".

13. Baumann, Ryan; Porter, Dorothy; Seales, W. (2008). "The Use of Micro-CT in the Study of Archaeological Artifacts". {{cite web}}: Missing or empty |url= (help)

14. Bukreeva, Inna; Alessandrelli, Michele; Formoso, Vincenzo; Ranocchia, Graziano; Cedola, Alessia (2017). "Investigating Herculaneum papyri: An innovative 3D approach for the virtual unfolding of the rolls". arXiv:1706.09883.