by Wikipedia

Accessed: 4/13/19

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Michio Kushi

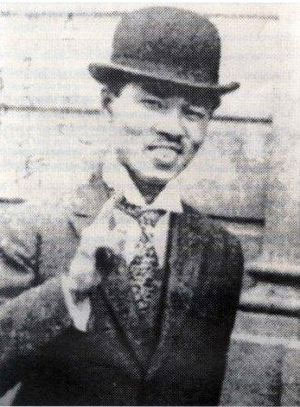

Michio Kushi (久司 道夫 Kushi Michio); born 17 May 1926 in Japan, died December 28, 2014, helped to introduce modern macrobiotics to the United States in the early 1950s. He lectured all over the world at conferences and seminars about philosophy, spiritual development, health, food, and diseases.

Background

After World War II, Kushi studied in Japan with macrobiotic educator, George Ohsawa. Since coming to America in 1949, Michio Kushi and Aveline Kushi, his wife, founded Erewhon Natural Foods, the East West Journal, the East West Foundation, the Kushi Foundation, One Peaceful World, and the Kushi Institute. They had written over 70 books.

In 1974, several staff members of East West Journal left that pioneering publication, weary of following the demanding macrobiotic diet and set on publishing a general-interest magazine for Aquarian readers. In October of that year, they published the first issue of New Age Journal (now known simply as New Age), a newsprint magazine that has grown to a circulation of 35,000, with monthly issues of nearly a hundred pages.

Where EWJ saw the world through the lens of macrobiotic philosophy, NAJ threw open its pages to participants in the human potential movement -- a grab bag of psychologies, diets, spiritualism, physical therapies, and back-to-the-land lifestyles, all aimed at producing personal growth and well-being in the midst of a competitive, materialistic society. New Age Journal shared with East West Journal the concept of a magazine as a tool. Beginning with issue number one, NAJ provided readers with news they could use. That focus has sharpened over the years. A typical issue of New Age offers recipes, gardening tips, yoga instructions, news of conferences and spiritual retreats, plus photo-essays and book and record reviews, to go with in-depth feature stories on the New Age groundswell. New Age also pays a frequent attention to other alternative media efforts, publishing a regular column on independent film and video and running features on community radio. A regular section called "Tools for Living" lists organizations, publications, businesses, and other sources of information, complete with addresses, related to a variety of topics. And nearly all New Age articles, on whatever topic, end with a section on "access" that tells readers how to follow up on what they've just read about.

Peggy Taylor, who has edited New Age since its third month of existence, explained, "The magazine serves a networking function, putting people in touch with one another." She continued:We always try to offer options for articles, for doing something about it. Our basic position is we all have a lot more participation in the world available to us than we are aware of, or that we use. And the reason we don't use it, most likely, is because we're not really aware of it.

The basic idea of the magazine is to empower people, to live more fully in the world, and take their high ideals -- about just being loving, caring people and wanting to see things work out on the planet -- and actually not just sit off in a closet somewhere and hope, but actually live it.

New Age projects a worldly mysticism that impels readers toward engagement and does not stop short of tweaking the noses of well-known spiritual leaders if it seems called for. At times, the magazine's desire to treat gurus like just plain folks shades over into cosmic gossip. A cover story in 1976 reported a split between Ram Dass and Joya -- two popular American teachers -- in loving detail, revolving around whether the two had broken their vows of celibacy with each other. "Look, I didn't fuck Ram Dass," reporter Stephen Diamond quoted Joya as saying, "but if I had, you'd better believe he'd stay fucked. My Sal -- that's my [presumably former] husband and lover of twenty years -- he tells me I'm the best in the world."

If New Age sometimes descends to earthly triviality, it more often clears the way for readers to become involved in whole-earth activism. New Age has covered the antinuclear movement since 1976, when eighteen activists peacefully occupied the construction site of a nuclear power plant at Seabrook, New Hampshire. Since then, the magazine has published frequent reports from Harvey Wasserman and opened its pages to strategy sessions for the likes of the Clamshell Alliance.

The June 1979 issue of New Age was devoted to discussing the future of the antinuclear movement, a growing groundswell that traces its philosophical roots to Gandhi and Thoreau and, more recently, to pacifists who opposed the Vietnam war. Feature articles by Wasserman and fellow Clamshell Alliance member Catherine Wolffe kept intact New Age's reputation for participatory journalism. Unlike sixties underground media, however, the rhetoric of imminent Armageddon was tempered by hope, and police and utility company officials were seen as unenlightened opponents rather than deadly enemies. An earlier cover story included a "demonstrator's guide" to antinuclear groups around the country and outlined plans for further demonstrations at Seabrook.....

[MISSING MATERIAL, pg. 284] ... popular issues on personal relationships, health, and money. While New Age has a broader scope than East West Journal, the staff lacks EWJ's grounding in a particular philosophy. As a result, New Age frequently flies off in pursuit of its staff's fancy of the moment. One of the subjects in which New Age has been keenly interested is money -- "prosperity consciousness," in Aquarian terminology.

Prosperity consciousness is the notion that commerce can serve as a vehicle for spiritual realization, that seekers who have long felt guilty about making money can "give themselves permission" to be rich, and that this is consistent with the Buddhist ideal of Right Livelihood. The Berkeley Monthly, for one, was founded and operated on this basis. The idea was proposed most enthusiastically in a New Age interview with Robert Schwartz, headlined "American Business Needs You," in 1976. Response to the interview was so favorable that Schwartz was asked to write a column for New Age, which he did.

Effused Schwartz: "I'm getting increasingly excited about the idea of the marketplace and the domain of business and entrepreneurship as valid places to explore our growing personal awareness." He went on to quote one Jim Nixon, "a Californian distantly related to ex-President Nixon," on the virtues of commerce: "Let me say first off that business, as a concept, has attracted too many attackers. It's currently popular to describe business as greedy and manipulative and overly competitive. In some cases, this is true; in other cases, not. I can find only one constant in all successful businesspeople. All successful businesspeople are businesslike -- and that is very Zen.' Wow."

Schwartz, a former consultant at Time, Inc., and a multimillionaire director of a school for executives in Tarrytown, New York, helped New Age accelerate and legitimize a desire in some Aquarian circles to make money. Through his column in New Age, Schwartz became a latter-day Dale Carnegie. He told eager readers that making money could make them better people, that they were all right to want to enjoy the material plane, and that their spiritual growth would proceed apace with the growth of their bank accounts.

New Age published other features on business-as-spirituality, including a special issue on Right Livelihood that further encouraged that trend. New Age endorsed the apparent contradiction of making money as a way of spiritual realization by emphasizing the degree of self-involvement business takes and divorcing the reality of acting in a commercial context from its consequences: the accumulation of material goods and the triumph of some individuals over other, evidently less [fortunate] ....

-- A Trumpet to Arms: Alternative Media in America, by David Armstrong

Kushi studied law and international relations at the University of Tokyo, and after coming to America, he continued his studies at Columbia University in New York City. Aveline preceded him in death (2001), as did their daughter (1995). Michio Kushi lived in Brookline, Massachusetts. He is survived by his second wife (Midori), four sons from his first marriage, and the resulting fourteen grandchildren and two great grandchildren. He died of pancreatic cancer at the age of 88.[1][2]

Achievements

• 1994 Kushi received the Award of Excellence from the United Nations Society of Writers.[3]

• 1999 Mentioned in the Congressional record in recognition of the dedication and hard work to educate the world about the benefits of a macrobiotic diet.[4]

• 1999 The Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History opened a permanent collection on macrobiotics and alternative health care in his name. The title of the collection is the "Michio and Aveline Kushi Macrobiotics Collection." It is located in the Archives Center.

1999 The Smithsonian Institution's National Museum of American History opened a permanent collection on macrobiotics and alternative health care in his name. The title of the collection is the "Michio and Aveline Kushi Macrobiotics Collection." It is located in the Archives Center.

Michio and his first wife Aveline were founders of The Kushi Institute, located in Becket, Massachusetts through 2016, but formerly in a converted factory building in Brookline Village, Massachusetts, adjacent to Mission Hill, Boston.

For their "extraordinary contribution to diet, health, and world peace, and for serving as powerful examples of conscious living", they were awarded the Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience Award in Sherborn, Massachusetts, on October 14, 2000.[5]

Criticism

Nutritionists have criticized Kushi's claim that a macrobiotic diet can cure cancer. Elizabeth Whelan and Frederick J. Stare have noted that:

Kushi's claim that cancer is largely due to his own versions of improper diet, thinking, and lifestyle is entirely without foundation. In his books, Kushi has recounted numerous case histories of persons whose cancer allegedly disappeared after following a macrobiotic diet. There are no available statistics on the outcome for all of these patients, but it is documented that at least some of them succumbed to their disease within a relatively short period. Reported testimonials of remission often uncovered the fact that the patients were also receiving conventional medical treatment at the same time.[6]

Books

• 1976 Introduction to Oriental Diagnosis. Red Moon Publications. ISBN 9780906111000

• 1977 The book of Macrobiotics. Japan Publications ISBN 9780870403811

• 1979 The book of Do-In. Japan publications. ISBN 9780870403828

• 1979 Natural Healing Through Macrobiotics. Japan Publications; (December 1979) ISBN 9780870404573

• 1980 How to See Your Health: Book of Oriental Diagnosis. Japan Publications (USA) (December 1980) ISBN 9780870404672

• 1982 Cancer and heart disease : the macrobiotic approach to degenerative disorders Japan publications. ISBN 9780870405150

• 1983 Your Face Never Lies. Wayne; (May 1, 1983) ISBN 9780895292148

• 1983 Macrobiotic pregnancy and care of the newborn. Japan publications. ISBN 9780870405310

• 1983 The Cancer Prevention Diet. St Martin's Press. ISBN 9780722515402

• 1985 Macrobiotic diet. Japan publications. ISBN 9780870405358

• 1985 Diabetes and hypoglycaemia : a natural approach. Japan publications. ISBN 9780870406157

• 1986 Macrobiotic child care and family health. Japan publications. 1986. ISBN 9780870406126

• 1986 On the Greater View: Collected Thoughts and Ideas on Macrobiotics and Humanity. Wayne NJ. ISBN 9780895292698

• 1990 AIDS, Macrobiotics and Natural Immunity. Japan Publications. ISBN 978-0870406805

• 1990 The Gentle Art of Making Love. Avery Pub Group (May 1990) ISBN 9780895294357

• 1991 The macrobiotic approach to cancer. Garden City Park. ISBN 9780895294869

• 1991 Macrobiotics and Oriental medicine. Japan publications ISBN 9780870406591

• 1992 The gospel of peace : Jesus's teachings of eternal truth. Japan publications. ISBN 9780870407970[7]

References

1. New York Times obituary for Michio Kushi, January 4, 2015, access 1/5/2015

2. Lewin, Tamar (January 15, 2013), "Michio Kushi, Advocate of Natural Foods in the U.S., Dies at 88", The New York Times

3. http://www.kushimacrobiotics.com/pdf/201994.pdf

4. https://www.congress.gov/congressional- ... le/E1138-1

5. The Peace Abbey Courage of Conscience Recipients List Archived 2009-02-14 at the Wayback Machine

6. Stare, Frederick J; Whelan, Elizabeth. (1998). Fad-Free Nutrition. Hunter House Publishers. p. 127. ISBN 0-89793-237-4

7. http://explore.bl.uk/primo_library/libw ... 8279563UI0)=creator&dum=true&tb=t&indx=1&vl(freeText0)=michio%20kushi&vid=BLVU1&fn=search

External links

• Smithsonian Institute's Michio and Aveline Kushi Macrobiotics Collection

• More information: http://www.michiokushi.org

• A live Interview with Michio Kushi

• Kushi Institute in Massachusetts

• Letter from Michio: A message On behalf of Michio Kushi

• Kushi institute in Lisbon, Portugal

• Kushi Institute in Zagreb, Croatia

• Kushi Institute in Barcelona, Spain

• Kushi Institute in Amsterdam, the Netherlands