by Ashim Kumar Bhattacharyya

Copyright © 2006 by Ashim Kumar Bhattacharyya

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

Chapter 2: Vedas.

Hindu Dharma is based on the teachings of the Vedas. The Vedas are the highest authority in all matters about Hindu religion and philosophy. Swami Vivekananda, the foremost disciple of Shri Ramakrishna, in his speech in 1893 at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago said: "The Hindus have received their religion through revelation, the Vedas. They hold the Vedas are without beginning and without end. It may sound ludicrous, that a book can be without beginning or end. But by the Vedas, no books are meant. They mean the collected treasury of spiritual laws discovered by different people at different times. Just as the Law of Gravitation acted before its discovery by humanity and would continue to act if all humanity forgot it, so it is with the laws that govern the spiritual world. The discoverers of these laws are called 'Rishis', and we honor them as perfected beings".

Nobody knows when the Vedas were revealed and how long it took to be revealed to the Rishis; it may be 8,000 years ago, it may be more. Not one of these religious revelations is of modern date, but they are as fresh today as they were when they were revealed to the Rishis.

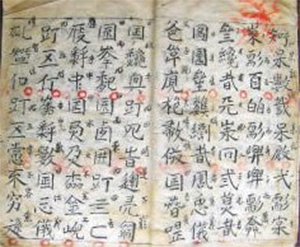

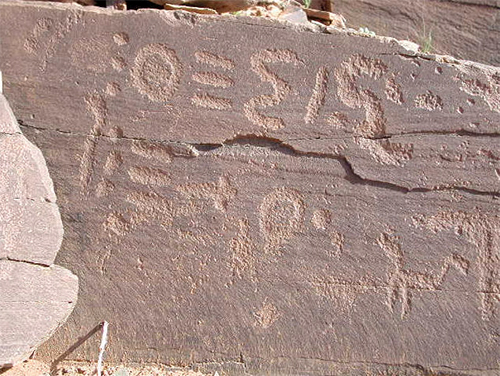

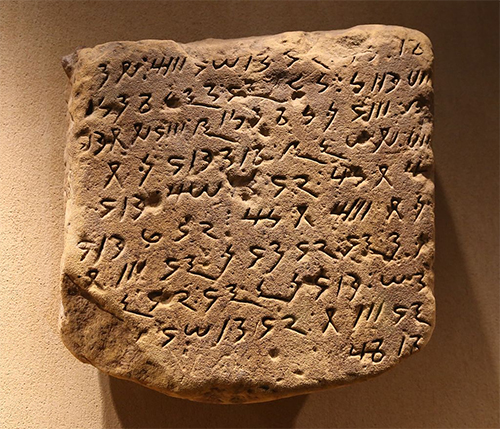

Vedas are written in an archaic form of Vedic or ancient Sanskrit -- a difficult language belonging to Indo-European family of languages. The Sanskrit word 'Veda' means knowledge, especially sacred knowledge. The ancient Indian Rishis considered the knowledge or truths revealed to them by God in their spiritual practices so sacred that they did not put them in writing. They preserved them in their memory and taught them to deserving students through verbal instructions. A Rishi, named Krishna Dvaipayana Vyasa collected them and recorded them in four books: 1) Rik Veda 2) Sama Veda 3) Yajur Veda and 4) Atharva Veda. Rik Veda is considered to be the oldest of the four Vedas. According to best estimates by many scholars, Vedas were written at least four thousand years ago.

Rik Veda is the compilation of Riks, which are hymns, that is mantras in verses. These mantras are recited by the 'Hota' priest to invite the deities to the Yajna that is sacrifice. Sama Veda is the collection of Samans, meant to be sung by the 'Udgatri' priest', the singer priest. Yajur Veda is the collection of the Yajus, the mantras, which are not in verses and used by the 'Adhvaryu' priest, the chief executor of the sacrificial rites. Atharva Veda consists of a special class of Vedic texts known as 'Chandas'.

Vedas are collected treasury of spiritual truths as discovered by Rishis at different times. Since the discoveries of the truths were made through spiritual practices, the Rishis believed that these truths were divine in origin, meaning the truths were revealed to them by God. Vedas are thus considered 'Apaurasheya' that is divine. Since the truths were revealed, the truths were thus 'Shruti' that is which was heard; that is why the Vedas are also known as 'Shruti'. The 'Shruti' is considered eternal and universal in truth and represents the 'Sanatana Dharma'. The Vedas contain the fundamental truths about Hindu Dharma. They are infallible source of the highest reason, antecedent to human experience and therefore free from human defects whatsoever. They are the authority; they provide the knowledge of God. Shri Ramakrishna said the Vedas and all other sacred books do not contain God; they give only hint that is only information about God.

Book 1

HYMN I. Agni.

1 I Laud Agni, the chosen Priest, God, minister of sacrifice,

The hotar, lavishest of wealth.

2 Worthy is Agni to be praised by living as by ancient seers.

He shall bring hitherward the Gods.

3 Through Agni man obtaineth wealth, yea, plenty waxing day by day,

Most rich in heroes, glorious.

4 Agni, the perfect sacrifice which thou encompassest about

Verily goeth to the Gods.

5 May Agni, sapient-minded Priest, truthful, most gloriously great,

The God, come hither with the Gods.

-- The Rig Veda. translated by Ralph T. H. Griffith

In each of the four Vedas, the bulk portion, called 'Karma Kanda', deals with details about Yajna (rituals), which were the ancient form of worship. The 'Karma Kanda' is subdivided into three parts: 1) Samhita 2) Brahmana and 3) Aranyaka. The rest, called 'Jnana Kanda', deals with the philosophy or knowledge. This part is also called the 'Upanishads' meaning devoted to knowledge. This part containing the knowledge portion of the Vedas occurs usually at the end of the Veda, so this knowledge portion is also commonly known as 'Vedanta' -- "anta" meaning last or end; thus, 'Vedanta' means the last part or end portion of the Veda.

Each Veda has its own customary Brahmana, Aranyaka and Upanishad.

Rik Veda --

Brahmanas: Aitereya and Kaushitaki or Sankhayana

Aranyakas: Aitereya and Kaushitaki or Sankhayana

Upanishads: Aitereya (part of Aitereya Samhita) and Kaushitaki (part of Kaushitaki or Sankhayana Aranyaka)

Sama Veda --

Brahmanas: Chandogya, Tandya and Jaiminiya or Talavakara

Aranyaka: Jaiminiya or Talavakara and Chandogya

Upanishads: Chandogya (part of Chandogya Brahmana) and Kena (part of Jaiminiya or Talavakara Brahmana)

Yajur Veda has two school: a) Shukla Yajur Veda and b) Krishna Yajur Veda (see later)

Shukla Yajur Veda --

Brahmana: Satapatha

Aranyaka: Brihadaranyaka

Upanishads: Isha (part of Vajasaneya Samhita) and Brihadaranyaka (part of Satapatha Brahmana)

Krishna Yajur Veda --

Brahmana and Aranyaka are considered together in Taittiriya Samhita and contains Maitrayani Brahmana

Upanishad: Katha and Svetasvatara

Atharva Veda --

Brahmana: Gopatha

Upanishad: Prasna, Mundaka and Mandukya

No Aranyaka of this Veda is known.

The Samhita is the collection of hymns, that is mantras in adoration of Brahman, the Supreme Spirit. It contains sacred prayers, invocation of different deities, sacred verses for chanting at the sacrifices, the sacrificial formulas, blessings and curses. Hymns praising personal gods (Ishvara) are also in this part. The Sama Veda Samhita and Yajur Veda Samhita mostly describe the Yajnas, the sacrificial rites.

The Brahmana deals with various aspects of the theory and practice of sacrificial rites. All mantras are intended to serve essentially for ritualistic purpose and the Brahmanas prescribe the manner in which they are to be used to serve that purpose. So, each of the Brahmanas is connected with one or other of the Samhitas.

The Brahmanas describe in details the topics of 'Karmavidhana', 'Arthavada', 'Ninda', 'Prasamsa', 'Purakalpa', and 'Parakriti'. Karmavidhana or simply Vidhi is the principle part of the Brahmana and sets forth the various details about a particular Yajna or sacrifice such as the proper time and place, the rite of initiation, the priests, the sacred fires, the divinities, the mantras, the oblations, the utensils and other materials, the Dakshina (sacrificial fee or gifts) and the expiation rites. In short, it contains the rules of performing particular rites. Arthavada provides the many explanatory remarks on the meaning of particular rite and mantra, the reason why a certain rite must be performed in a certain way. Ninda or censure refers to the controversial remarks contained in the Brahmanas. The sacrificer, that is the person performing the Yajna that is the sacrificial rite, is cautioned about making mistakes in performing the sacrificial rite. Prasamsa means praise and comprises principally those phrases that tell us what will be the desired effect of performing a particular rite with the proper knowledge. Purakalpa means performance of sacrificial rites in former times. Under this topic come many stories of the fights between Devas and Asuras, to which the origin of many rites is attributed, as also all legends on the sacrifices performed by the gods. Parakriti means the achievement or feat of another. This section comprises the stories of certain performances of renowned Shrotriyas, or sacrificial priests, of gifts presented by kings to the priests, and the successes they achieved.

The most important among the Brahmanas are the Aitareya and Kaushitaki belonging to Rik Veda, Taittiriya belonging to Krishna Yajur Veda, Satapatha belonging to Shukla Yajur Veda, Jaiminiya and Tandya belonging to Sama Veda and Gopatha belonging to Atharva Veda.

Aitareya Brahmana (Rik Veda) concerns mainly the duties of the Yajna priest, the Hotr. It also provides the procedure for Pashujaga (animal sacrifice) and Rajasuya Yajna.

Kaushitaki Brahmana (Rik Veda) covers more or less the entire Yajna (sacrificial) procedure.

Satapatha Brahmana (Shukla Yajur Veda) covers the basic sacrificial ritual, speaks of the mystical significance of the various aspects of the sacred fires, expiation rites, and the Sautramani Yajna. It also deals with the Asvamedha Yajna and briefly, the Purusamedha and Sarvamedha Yajnas. This Brahmana also considers the Pavargya ceremony (introductory to the Soma Yajna).

Jaiminiya Brahmana (Sama Veda) is the best source of information about the technique of the Samagas (the priests who chant or recite the Sama Veda).

Tandya Brahmana (Sama Veda) is chiefly concerned with the Soma sacrifice in all its varieties. It describes in detail the Sattras (sacrificial sessions) and the Vratya-stomas (hymns of praise).

Gopatha Brahmana (Atharva Veda) contains myths, legends and parables that explain the various ceremonies in the Vedic ritual. It stresses that sacrificial rites performed without the help of a priest is bound to fail.

The Aranyakas mark the transition from the ritualism of the Brahmanas to the spiritualism of the Upanishads. Aitereya Aranyaka, belonging to the Rik Veda, consists of five books. The 2nd and the 3rd books are specifically theosophical in nature. The first three sections of the second book teach the Prana-Upasana (worship of 'Prana' or vital power). The last three sections of the 2nd book make up the Aitereya Upanishad. The 3rd book deals with the Samhita-Upasana (unified form of worship). In other parts, it describes the sacrificial ceremonies of the Mahavrata.

Kaushitaki or Sankhayana Aranyaka, belonging to the Rik Veda, consists of three books; the first two are ritualistic and the 3rd forms the Kaushitaki Upanishad.

Taittiriya Aranyaka, belonging to the Krishna Yajur Veda, in its first six books describe the Vedic sacrificial rituals such as the Sarvamedha, the Pitrmedha, and the Pravargya Yajnas. The next three books make up the Taittiriya Upanishad. The 10th or the last book is known as the Mahanarayana Upanishad.

The first three Adhyayas (chapters) of the 14th Kanda (section) of the Satapatha Brahmana, belonging to the Shukla Yajur Veda, are called Aranyaka and they deal with the Pravargya Yajna or sacrifice. The last six Adhyayas of this Kanda is the Brihadaranyaka Upanishad.

The division of the Vedas in two parts, the Karma Kanda, dealing with Karma, or ritualistic worship, and the Jnana Kanda, dealing with knowledge of Brahman, serves two types of minds. Thus, Karma Kanda serves those seeking happiness by fulfilling desires on earth and in heaven after death, whereas the Jnana Kanda serves those seeking the highest knowledge, the knowledge of Brahman, and or Atman thus attain liberation that is Moksha. Thus, the Karma Kanda of the Vedas guides the pleasure-seeking person, by stages, from physical enjoyments to the supreme experience of Moksha. The Vedic Rishis realized that sudden and blunt imparting of knowledge about the transcendental Brahman, unknown to and unknowable by the senses and the mind would confuse people attached to the world. They therefore did not renounce or discard the ritualistic actions, though these were considered inferior to the realization of Brahman. In the Jnana Kanda, that is the Upanishads, they have shown how the aspirant can finally attain the knowledge of Brahman through the rituals and what help can be rendered by the ritual for attaining Knowledge or Jnana.

The Vedas are the foundation of the Hindu Dharma. They contain eternal or revealed truths about the nature of supreme reality, the soul and its destiny and the creation; these cannot be understood through our sensory system and reasoning based on them. The Vedas also tell us about the cosmic divinities, the various heavens, the different courses followed by the soul after death and other similar phenomena beyond the reach of our senses. Vedas are concerned with the ultimate questions of human life; they are

Who are we?

Why are we born?

What in us, if anything, transcends death?

By knowing that can we transcend all pain?

The Vedas are the collected treasury of spiritual laws discovered by different Rishis or sages in different times. These are the laws that govern the spiritual world. The moral, ethical and spiritual relations between individual soul and the Supreme Soul that is Brahman are explored in the Vedas.

The Vedas teach the supreme reality that is the 'Supreme Spirit' or the 'Supreme Being' (Brahman), is all-pervading, uncreated, self-luminous, eternal spirit, the final cause of the universe, the power behind all tangible forces, the consciousness, which animates all conscious beings.

HYMN XXXVII. Maruts.

1 SING forth, O Kaṇvas, to your band of Maruts unassailable,

Sporting, resplendent on their car

2 They who, self-luminous, were born together, with the spotted deer,

Spears, swords, and glittering ornaments.

3 One hears, as though ’twere close at hand, the cracking of the whips they hold

They gather glory on their way.

4 Now sing ye forth the God-given hymn to your exultant Marut host,

The fiercely-vigorous, the strong.

5 Praise ye the Bull among the cows; for ’tis the Maruts’ sportive band:

It strengthened as it drank the rain.

-- The Rig Veda. translated by Ralph T. H. Griffith

The Vedas point out that this impersonal supreme reality that is Brahman is the supreme truth. Vedas give us the knowledge of Brahman, the 'Supreme Spirit' or the 'Supreme Being'.

May Agni, sapient-minded Priest, truthful, most gloriously great, The God, come hither with the Gods. Whatever blessing, Agni, thou wilt grant unto thy worshipper, That, Aṅgiras, is indeed thy truth....

Watch ye, through this your truthfulness, there in the place of spacious view

Indra and Agni, send us bliss....

Thou hast filled all the region with thy greatness: yea, of a truth there is none other like thee....

He who like Savitar the God, true-minded protecteth with his power. All acts of vigour, Truthful, like splendour, glorified by many, like breath joy-giving,—all must strive to win him....

So now, O truthfullest Invoker Agni, worship this day with joy-bestowing ladle....

Truthful art thou, and blameless, searcher out of sin: so thou, Strong Host, wilt be protector of this prayer....

Be this thy truth, Vaiśvānara, to us-ward: let wealth in rich abundance gather round us....

Ye Gods who yonder have your home in the three lucid realms of heaven, What count ye truth and what untruth?...

The flowing of the floods is Law, Truth is the Sun's extended light....

Now of a truth these be the very sunbeams wherewith our fathers were of old united....

He is a wild thing of the flood and forest: he hath been laid upon the highest surface. He hath declared the lore of works to mortals, Agni the Wise, for he knows Law, the Truthful....

These Sons of yours well skilled in work, of wondrous power, brought forth to life the two great Mothers first of all. To keep the truth of all that stands and all that moves, ye guard the station of your Son who knows no guile....

I in truth am fierce and strong and mighty. I bent away from every foeman's weapons....

Enrich the man more liberal than the godless. May we, ye Gods, be strong with food rejoicing. Endowed with understanding, I have uttered this truth, for all to hear, to Earth and Heaven....

Thou who in every way supreme in earthly power, rejoicing, by thy mighty strength hast waxen great,— He is the God spread forth in breadth against the Gods: he, brahmaṇaspati, encompasseth this All. From you, twain Maghavans, all truth proceedeth: even the waters break not your commandment....

I crave the grace of heaven's two chief Invokers: the seven swift steeds joy in their wonted manner. These speak of truth, praising the truth eternal, thinking on Order as the guards of Order....

The Spring that fails not with a hundred streamlets, Father inspired of prayers that men should utter, The Sparkler, joyous in his Parents' bosom, him, the Truth-speaker, sate ye, Earth and Heaven....

Yea, Much-invoked! in safety through thy glories alone thou speakest truth as Vṛtra's slayer.

-- The Rig Veda. translated by Ralph T. H. Griffith

The Vedas are intended to serve for spiritual enlightenment and self-culture. The study of the Vedas is, therefore, not merely to tell our intelligence but to purify and enrich the soul. For the study of the Vedas, one must have a teacher or Guru. A good teacher not only explains the scripture but also most importantly touches the life of the student. A good teacher or Guru helps to awaken the spiritual consciousness within the student. There are many instances that the first spiritual awakening came to an aspirant through a perfected soul or Guru. One should do well to be on the lookout for a perfected soul and when one finds such a person accepts that person as one's Guru and place oneself unreservedly under his guidance and teachings. Shri Ramakrishna said "God alone is the guide and Guru of the universe. He who can himself approach God with sincerity, earnest prayer and deep longing, needs no Guru. But such deep yearning of the soul is very rare, and hence the need of a Guru." Swami Vivekananda in his address on Bhakti Yoga considered the qualifications of a proper Guru as 'sinless, unselfish, and knowing the spirit of the scripture'.

Mahavakyas

There are four Mahavakyas or great statements in the Vedas:

Tat tvam asi (Chandyogya Upanishad V1.8.7 in Sama Veda) -- Thou art That.

Aham Brahmasi (Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 1.4.10 in Shukla Yajur Veda) -- I am Brahman.

Ayam Atma Brahma (Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 115.19 in Shukla Yajur Veda) -- This Self is Brahman.

Prajnanam Brahma (Aitereya Brahmana III.1.3 in Rik Veda) -- Knowledge is Brahman.

The first three Mahavakyas speak of the divinity of the indwelling Self in man, that is, the Atman or the soul of the man. These concepts imply not only the divinity of humans but also the identity of Brahman with Atman. The fourth Mahavakya states that supreme knowledge is Brahman and provides a definition of Brahman. Meditating on these Mahavakyas, one realizes oneness with Brahman.

Rik Veda

The Rik Veda is the oldest of the four Vedas. As stated earlier, Rik Veda was written about five thousand years ago. It is considered as the central 'canon' of the Vedic religion and of the Hindu Dharma that emerged from it.

The Rik Veda Samhita is arranged in ten books or mandalas. Six of the mandalas are devoted each to the hymns of a single Rishi or family of Rishis. For example, 2nd mandala is devoted chiefly to the suktas of the Rishi Gritsamada, the 3rd and the 7th to Vishvamitra and Vashistha, the 4th to Vamadeva, the 6th to Bharadvaja. The 5th mandala is devoted to the hymns of the house of Atri. The 9th mandala is devoted to Soma. In the 10th mandala we find hymns by several Rishis. In this mandala, one finds the great hymn of the creation (Purusha Sukta). Many scholars think that in this mandala the first origin of the Vedic philosophy 'Brahmavada' is found.

In each of the mandalas, the suktas are addressed first to Agni, the Fire God followed by to Indra and other Gods such as Brishaspati, Surya, Ribhu, Usha and others.

The topics dealt with in the Rik Veda Samhita fall into three groups. The first group deals with the deities like Agni, Indra, Varuna and others. The second group is concerned with philosophical speculations like the origin of the universe and the real nature of human beings. The third group deals with several secular subjects like marriage, wars, praise for generosity and so on.

The Vedic deities are usually listed as thirty-three -- eight Vasus, eleven Rudras, twelve Adityas, Indra and Prajapati. These deities are assigned to the three regions of the universe -- the earth (Prithivi), heavens (dvyau) and the intermediary space (Antariksha). Though they appear like personification of forces of nature, they are facets of Brahman, the Supreme Truth. This Veda ((1.164.46) makes the categorical statement 'Ekam sat viprah vahudha vadanti' (Truth is one, sages call it by various names). Thus, the Veda teaches 'Eka-devata-vada' or monotheism.[???!!!] However, the advocacy of 'Saguna Upasana that is God with form or attribute is also predominant in the Veda.

As regards the philosophical speculations of this Veda, we find that it is the origin and repository of almost all the later ideas of Vedanta including knowledge (Jnana) and devotion (Bhakti), though some of them are in the seed form.

The philosophical speculations about the origin of the universe, two streams of thought are found in the Rik Veda. They are 'creation' and 'evolution' -- both of which are also found in the Vedantic thoughts later. Statements like 'God created this world out of Himself, "rules over it' etc are found in the Veda.

The Rik Veda declared the existence of the soul as an eternal entity. It teaches to pray for 'immortality' (Amritatva). However, the Veda did not relegate the life on earth to the background. In the Veda, life here and life hereafter have been harmonized.

Ruler of sacrifices, guard of Law eternal, radiant One, Increasing in thine own abode....

O mighty Indra, Gotama's son Nodhas hath fashioned this new prayer to thee Eternal, Sure leader, yoker of the Tawny Coursers....

With flame insatiate, like eternal might; caring for each one like a dame at home; Bright when he shines forth, whitish mid the folk, like a car, gold-decked, thundering to the fight....

All men are joyful in thy power, O God, that living from the dry wood thou art born. All truly share thy Godhead while they keep, in their accustomed ways, eternal Law....

Thine are King Varuṇa's eternal statutes, lofty and deep, O Soma, is thy glory....

To whom thou, Lord of goodly riches, grantest freedom from every sin with perfect wholeness, Whom with good strength thou quickenest, with children and wealth—may we be they, Eternal Being....

May Indra, girt by Maruts, be our succour. Whose home eternal through his strength surrounds him on every side, his laud, the earth and heaven...

From days eternal hath Dawn shone, the Goddess, and shows this light to-day, endowed with riches....

In the sky's lap the Sun this form assumeth that Varuṇa and Mitra may behold it. His Bay Steeds well maintain his power eternal, at one time bright and darksome at another....

Obedient to the rein of Law Eternal give us each thought that more and more shall bless us....

Thou, Indra, without effort hast let loose the floods to run their free course down, like chariots, to the sea, like chariots showing forth their strength. They, reaching hence away, have joined their strength for one eternal end, Even as the cows who poured forth every thing for man, Yea, poured forth all things for mankind....

All falsehood, Mitra-Varuṇa! ye conquer, and closely cleave unto the Law Eternal....

Two Birds with fair wings, knit with bonds of friendship, in the same sheltering tree have found a refuge. One of the twain eats the sweet Fig-tree's fruitage; the other eating not regardeth only. Where those fine Birds hymn ceaselessly their portion of life eternal, and the sacred synods, There is the Universe's mighty Keeper, who, wise, hath entered into me the simple....

Ye men do worship to Indra seated on the grass, eternal....

Upholding that which moves and that which moves not, Ādityas, Gods, protectors of all being, Provident, guarding well the world of spirits, true to eternal Law, the debt-exactors....

SOMA and Pūṣan, parents of all riches, parents of earth and parents of high heaven, you twain, brought forth as the whole world's protectors, the Gods have made centre of life eternal....

Agni most bright and fair with song we honour, yea, the adorable, O Jātavedas. Thee, envoy, messenger, oblation-bearer, the Gods have made centre of life eternal....

Agni, burn up the unfriendly who are near us, burn thou the foeman's curse who pays no worship. Burn, Vasu, thou who markest well, the foolish: let thine eternal nimble beams surround thee....

Agni. RUBBED into life, well stablished in the dwelling, leader of sacrifice, the sage, the youthful, here in the wasting fuel Jātavedas, eternal, hath assumed immortal being....

In the floods' home art thou enkindled, Agni, O Jātavedas, Son of Strength, eternal, exalting with thine help the gathering-places....

Peer of each noble thing, yea, all excelling, all creatures doth he know, he slayeth Śuṣṇa. Our leader, fain for war, singing from heaven, as Friend he saved his lovers from dishonour. They sate them down with spirit fain for booty, making with hymns a way to life eternal.

-- The Rig Veda, translated by Ralph T. H. Griffith

Agni the God the first among the Immortals...

For glory, Agni, day by day, thou liftest up the mortal man to highest immortality.

-- The Rig Veda, translated by Ralph T. H. Griffith

From the group of Suktas that is hymns dealing with the secular side of life, we get some idea about the nature of the society of those times. Social life was permeated by spiritual consciousness. People strongly believed in 'Samanvaya' that is harmonizing life in this world with the one in the next. Truth (Satya) and Dharma (righteousness) are praised and immortality (Amritatva) as the goal of life accepted. Varna System in the society has already taken roots. Monogamy, polygamy, 'Svyamvara' system (bride choosing her husband), all existed in the society. Agriculture and animal management were the chief means of livelihood. Equitable distribution of wealth was recommended. Civilization was developed and fine arts encouraged. Priests and kings were powerful. System of sacrifices had evolved to a high degree of perfection.

Sama Veda

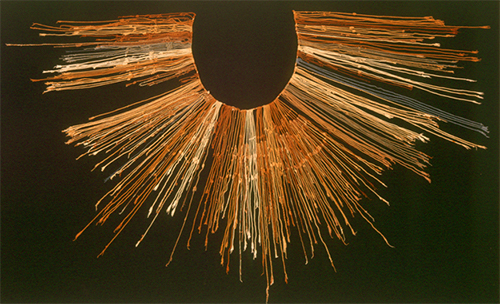

Sama Veda is also known as the book of Sama Gana (holy songs). The hymns are chanted or sung by Udgatri priests during the performance of important Yajnas, that is, sacrifices connected to prepare the 'Soma' juice. Thus, this Veda serves mainly ritualistic purpose. The hymns are mainly collected from the Rik Veda but are arranged in a different order with minor variations.

It is impossible to state with any accuracy the period when Sama Veda was composed out of Rik Veda. It was Sama Gana (holy songs) that served as the source of priesthood; its recitation pleased everyone because of the melodious quality of the Sama Gana. In fact, the Sanskrit term 'Saman' means 'soothing and pleasing'.

There are 1875 verses in the Sama Veda. It is a Veda chiefly of Upasana, that is worship and contemplation, essential for the realization of Brahman.

The Veda is divided into three parts: 1) Purva Archika, 2) Uttara Archika and 3) Maha Namni Archika. The Purva Archika is divided into four Kandas: 1) Agneya Kanda, 2) Aindra Kanda, 3) Pavmana Kanda 4) Aranyaka Kanda.

In Purva Archika, there are two song manuals: the Gana or congregational songs and Aranya Gana, which the recluse and seekers of salvation sing in the forest solitude. In the Uttara Archika, there are also two song manuals: the Uhagana and the Uhyagana.

Yajur Veda

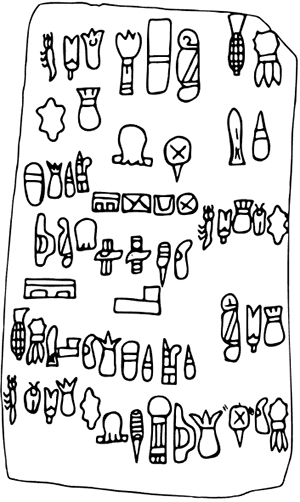

The Yajur Veda is a collection of Yajus, which are mantras in prose; these mantras are useful to the 'Adhvarya' priest in performing the Yajnas (sacrifices). This Veda is essentially ritualistic and treats the entire sacrificial system. It deals with the duties of the Advaryu (the fire-priest) who is responsible for performing the various sacrificial rites.

The Yajur Veda has in all 1975 verses spread over forty chapters or Adhyasas. Nearly three to four hundred mantras of Yajur Samhita are common with Rik Samhita.

There are two schools of Yajur Veda: 1) Krishna Yajur Veda and 2) Shukla Yajur Veda. Rishi Vyasa taught Krishna Yajur Veda to Vaisampayana; while the Shukla Yajur Veda is associated with Vajasaneya Yajnavalkya. Thus, Shukla Yajur Veda is also known as Vajasaneyi Samhita. The Shukla Yajur Veda's entire Samhita and its Brahamana called the Satapatha Brahmana come in two distinct versions: 1) the Madhyandina and 2) Kanva. The Shukla Yajur Veda is traditionally the oldest recession of the Yajur Veda. The main Brahmana of Shukla Yajur Veda is Satapatha Brahmana. The Madhyandiniya Satapatha Brahmana has one hundred chapters, fourteen Kandas, four hundred thirty-eight Brahmanas, and seven thousand six hundred twenty-four Kandikas. The teacher of the Brahmana is Yajnavalkya. However, in four Kandas (chapters 6-9), the name of Rishi Sandilya is found. The Kanva Samhita also contains forty chapters (Adhyayas) and follows the same subject matter. The Yajur Veda is associated with two Upanishads, the 'Isha' and the 'Brihadaranyaka'. The 'Isha' Upanishad mainly reproduces the fourteenth chapter of the Yajur Veda with slight variation at the close. The 'Brihadaranyaka' Upanishad is the last part of the Satapatha Brahmana.

The main content of the Yajur Veda is the mantras that are short prose passages addressed to various objects that are used in the rituals. The Yajur Samhita deals mainly with Yajnas like Agnistoma, Vlajapeya and Rajasuya. In the Shukla Yajur Veda, the entire text is of this nature. In the Krishna Yajur Veda, the original mantras are mixed with explanatory passages.

Atharva Veda

Of the Vedas, the Atharva Veda is listed as the last in order. It contains 5977 verses. According to the tradition, Atharva Veda is mainly the contributions of two sages, Atharvan and Angira.

The Atharva Veda has remarkable references to various aspect of spiritual and temporal importance like Brahmavidyli, Prithivi or earth, kingship, marriage, treatment of ailments, building construction, trade and commerce. However, most of the hymns of the Atharva Veda is to appease (the demons), to bless (friends) and to curse. Because of this, the Veda did not find much favor with the priesthood. In this Veda one finds prayers for health and long life (Ayusya Mantra), for happiness and prosperity (Paustikani). The Veda also discusses various relationships with women (Strikarmani). Another section deals with Rajakarmani (involving the king). Also, there are sections, which are intended for securing harmony in domestic, social and political spheres. This Veda is also connected with later development of the Tantric System and mentions the importance of Japa or chanting of mantra to achieve material and spiritual benefits, which forms an integral part of Indian religious mysticism till today.

The Atharva Veda gives us an interesting picture of the society of its times. The land in which the people lived extended from 'Gandhara' (present Afghanistan) to 'Magadha' (Bihar) and 'Anga' (Bengal). The Varna system had been well established in the society. The first three Varnas were called 'Aryas' and last as 'Sudra'. But people lived in harmony. Kings were powerful. Trade and commerce were prosperous though agriculture was the mainstay of the people. Sometimes the 'Kshatriya' kings harassed the 'Brahmanas'. The cow was venerated and 'Godana' (gift of a cow) was considered meritorious. The institution of marriage was similar to that in the Rik Vedic times.