The "Avaca" Inscription and the Origin of the Vikrama Era

by Richard Salomon

Journal of the American Oriental Society , Jan. - Mar., 1982, Vol. 102, No. 1 (Jan. - Mar., 1982), pp. 59-68

March, 1982

THE "AVACA"' INSCRIPTION AND THE ORIGIN OF THE VIKRAMA ERA*

BY RICHARD SALOMON

UNIVERSITY OF WASHINGTON

A Kharosthi inscription on a Buddhist relic casket of uncertain provenance, first published by Bailey in 1978, is here re-edited. The re-interpretation of this inscription enables us to more fully reconstruct the previously obscure dynasty of kings who ruled Apraca or Avaca (modern Bajaur in north-western Pakistan) in the 1st centuries B.C. and A.D. Moreover, the date of the inscription samvatsarae tresathimae 20 20 20 3 maharayasa ayasa atidasa ('in the year 63 of the late King Azes ') provides the long-awaited explicit evidence that the Indo-Scythian king Azes I was the founder of the "Vikrama" era of 58-7 B.C.

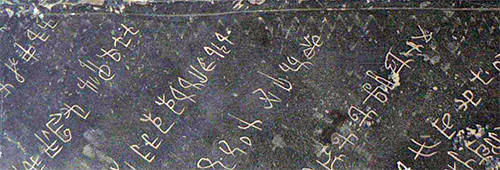

H. W. BAILEY RECENTLY PUBLISHED two significant new inscriptions under the title "Two Kharosthi Casket Inscriptions from Avaca" in JRAS, 1978, 3-13. The first of these inscriptions is particularly important; for, in addition to its considerable philological and dialectal interest, it provides new historical data on (1) the reigns and genealogy of the hitherto little-known "Apracarajas" of Bajaur, and (2) the long-standing problem of the origin of the Vikrama era of 58-7 B.C. Since the historical significance of the inscription was not fully discussed by B, and since its reading and translation are subject to differences of opinion (as is so often the case with Kharosthi inscriptions), I have undertaken to present a new interpretation of the record in this article.

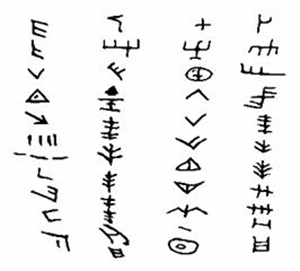

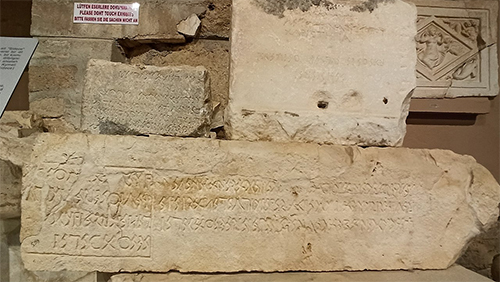

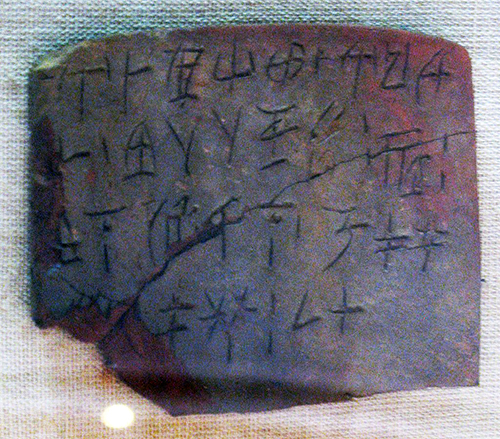

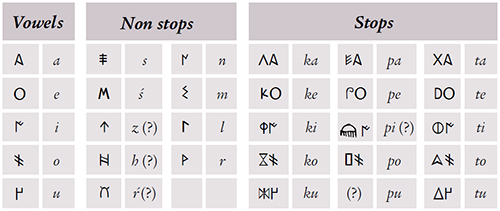

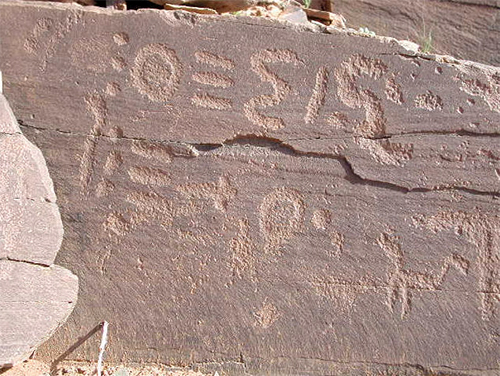

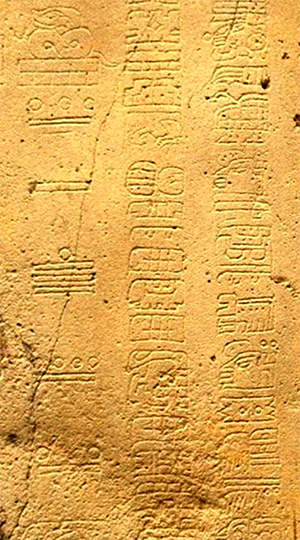

The inscription is a typical Buddhist dedication of a relic casket containing bodily relics (sarira) of the Buddha (bhagavato sakyamunisa) in Kharosthi script of the Scythian period (c. 1st century B.C.-1st century A.D.) and in the northwestern Prakrit dialect peculiar to Kharosthi documents. The dialect also shows a not-unusual admixture of non-Indic (i.e., Greek and Iranian) vocabulary.

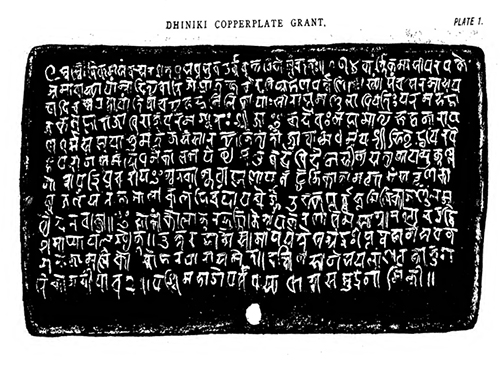

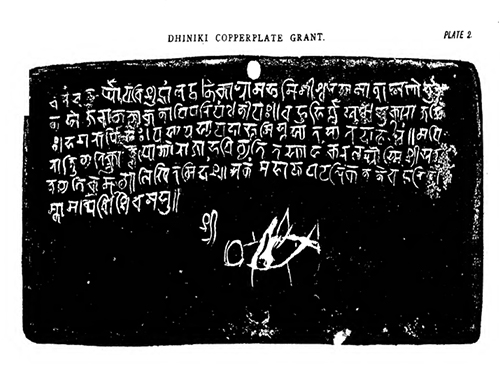

Before proceeding to a discussion of the historical value of the inscription, I will first offer my reading and translation of it. These differ considerably from B's, and such points of divergence in the text and translation will be indicated by italics. My readings are taken directly from the plates illustrating the casket in B's article; I have not seen the original. I have added punctuation marks to the text to facilitate its reading and interpretation.

I. The "Avaca"' Inscription.

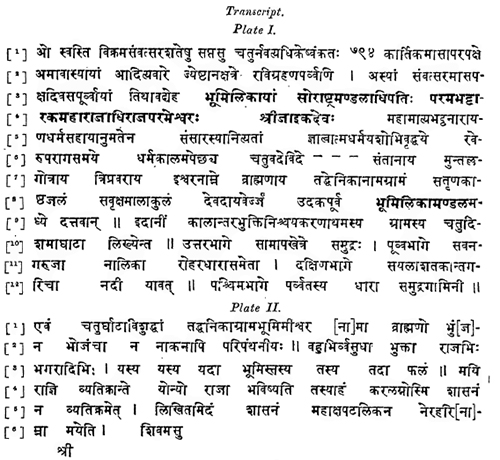

READING:

Line 1 [on the body of the casket] samvatsarae tresathimae 20 20 20 3 maharayasa ayasa atidasa kartiasa masasa divasae sodasae imena cetrike ksana idravarme kumare apracaraja-putre

2 ime bhagavato sakyamunisa sarira pradithaveti thiae gabhirae a pradithavitaprave (pa)tese. bramhapuna prasavati, sadha maduna ru-khanaka aji-putrae apracaraja-bharyae

3 sadha maulena ramakena, sadha maulanie dasakae, sadha spasadarehi -- vasavadatae, maha(e)dae, nikae ca, gahinie ya utarae.

4 pitu a puyae visnuvarmasa. avacarayasa

5 bhrada vaga stratego puyaite viyayamitro ya. avacaraya-maduka sabhaedata puyita.

6 [on the lid[2]] ime ca sarira muryaka-linate thubute ki (?) da-padiharia. avi ya ahethima-jimami pratithavanami pratitha(vita).

7 vasia pamcaviso.

TRANSLATION:

1 In the year sixty-three (63) of the late Maharaja Aya (Azes), on the sixteenth day of the month Karttika; at this auspicious (?) time Prince Indravarman, son of the Apracaraja,

2 establishes these body-relics of the Lord Sakyamuni in a long-lasting and revered place which is furnished with drinking wells. He (thereby) creates divine merit (for himself, and) together with (his) mother Ru-khanaka, daughter of Aji (and) wife of the Apracaraja,

3 with (his) maternal uncle Ramaka, with (his) maternal uncle's wife Dasaka, (and) with his sisters and wife -- (his sisters) Vasavadata (Vasavadatta), Mahaeda (?), and Nika, and (his) wife Utara (Uttara).

4 And (this is also done) for the honor of his father Visnuvarman. The Avacaraya's

5 brother, the Lord Commander Viyayamitra, is honored too. The mother of the Avacaraya, Sabhaedata, is (also) honored.

6 And these body-relics were prepared and presented from the stupa from (i.e., in) the Muryaka cave. And they were established in the Ahethimajima relic-shrine.

7 (In) the twenty-fifth (regnal) year.

NOTES:

Line 1:

samvatsarae tresathimae: The year 63 of the "Vikrama" era of 58-7 B.C., as will be shown in Part III of this paper. The inscription was therefore written in 5-6 A.D.

maharayasa ayasa atidasa -- The significance of this phrase will be discussed below in Part III.

imena cetrike ksana: The expression is somewhat irregular, the usual phrase in Kharosthi inscriptions being ise ksunammi or the like. For the instrumental imena cf. the Wardak vase inscription, line 1, imena gadrigrena (= Sansrit ghatikaya?) (K 170). cetrike (B reads -ka) is also unusual, but cf. the Saddo inscription (N. G. Majumdar, "List of Kharosthi Inscriptions" in Journal and Proceedings of the Asiatic Society of Bengal 20, 1924, 19, no. 57) . . . masaisa cetra di (vaase) ... I translate as it as B, 'auspicious,' with reservations. ksana without case ending is perhaps, as B suggests (10) a scribal error for ksane or ksanena.

Line 2:

pradithavidaprave: = Sanskrit *pratisthapita-prape (pra-pa, 'drinking well') (as B).

a: Three forms of the word for 'and' appear in this inscription: ca (lines 3, 6), ya (lines 3, 5, 6), and a (lines 2, 4). ya in the combination avi va = api ca (as here in 1.6) is elsewhere attested in Kharosthi in the Wardak vase inscription, 1.3 (K 168; see also his remarks on xcix); ya = ca also occurs twice in line 4 of the Kalawan inscription (SI 132). a is not known elsewhere in Kharosthi, but its sense is clear from the context in both occurrences in this inscription. It is probably no more than a graphic variant of the form ya, without representation of the glide y.

bramhapuna: B reads bramu-; but the second aksara is not the same as the mu of muryaka, 1.6. It appears to resemble the letter read as m[h]a in 1.3 of the Peshawar Museum inscription, K 157 and pl. xxx. The metathesis of h and m is typical of Prakrit in general.

The phrase brahmapuna prasavati is reminiscent of pumnam pasavati in Asokan rock edict IX.

Line 3:

maidlanie dasakae: B reads ma'ulani adasaka'e; but the right-hand stroke indicating the vowel e on the fifth character is clear in the photograph, and this provides the appropriate oblique feminine case ending of the first word. maulani = Sanskrit matulani, which means 'maternal uncle's wife,' not 'maternal aunt,' as B translates. The name is thus Dasaka (= Daksaka?), not Adasaka. sadha spasadarehi - vasavadatae, maha(e)dae, nikae ca, gahinie ya: B reads sadha s'pasa-darehi vasavadata'e mahaphida anika'e cagahine aya-utara'e, 'with sister (and) wife Vasavadata, in honor of grandfather Kinsman Cagahine and of (his) noble (and) eminent . . .' According to him (11), "Only one name follows" the phrase sadha spasadarehi; but a re-reading of the inscription shows that this is not so. The text after the following word vasavadata reads maha, then a letter which is not completely clear but looks like e. These are followed by two disconnected parallel slanting lines, which do not seem to represent any letters; nor is a mark of punctuation to be expected here. B apparently takes the first line as an i-vowel marker to be applied to the preceding aksara, which he reads as ph. But the line does not actually touch that letter, and is much longer than a normal i diacritic; and in any case the second parallel line is still left unexplained. The word is read by B as mahaphida, taken as a (very irregular) correspondent to Sanskrit pitamaha 'grandfather,' with an unattested reversal of the order of words in the compound and unexplained aspiration of the p.

I am inclined to dismiss both unattached lines as extraneous marks, and read the word as mahaedae, a feminine name, i.e., that of the second sister of Indravarman. (Note that a similar pair of superfluous parallel lines appears in the Wardak vase inscription between lines 2 and 3; K pl. xxxiii, upper left.) The last letter is again, as in maulanie, clearly e and not a, for the feminine oblique ending. For the form of the name, cf. sabhaedata below, 1.5.

The next four aksaras are read as in B, but divided as nikae ca, giving the name of Indravarman's third and last sister. Following this I read and divide gahinie ya utarae; and once again the vowels -ie are clear. gahini is obviously Sanskrit grhini 'wife'; ya is = ca (see note on a, line 2); and utara = Uttara is Indravarman's wife's name. Thus B's anikae = Greek [x] 'kinsman,' questionable at best,[3] is unnecessary, as is utara = udara, with unexplained devoicing.

The word gahini is intended to identify Utara as the wife, as distinct from the three sisters whose names precede it; for without this additional specification, it would not be clear from the preceding dvandva compound spasadarehi which of the names were sisters and which the wife.

Line 4:

avacarayasa: This variant spelling (also in 1.5) for apracaraja is slightly surprising. While -y- for -j- intervocalically is normal, -v- for -pr- is not. The combination pr is common and stable in the north-western Prakrit of the Kharosthi inscriptions (K cvii). Intervocalic -p- often becomes -v-, as in other Prakrits; but -pr- → -v- is otherwise unattested, as far as I have been able to determine. While a subscript or "otiose" (K 166) r is often added to such consonants as k, g, s, s, etc., apparently to indicate spirantization (K c, cxxv), this does not normally occur with p. Thus the r in pra seems to be the full semi-vowel, not an "otiose" diacritic. The unusual alternation of pr/v suggests a non-Sanskritic origin for the word apraca, and such proposed derivations as apratyak and apracya no longer seem likely. The word is probably a non- Sanskritic place name for the region now known as Bajaur. Since Kharosthi does not indicate long vowels, the quantities are indeterminate; the word is actually a{pr/v}aca. For convenience's sake, the full term will be written as "Apracaraja."

Line 5:

vaga: Iranian baga, to be taken here as a royal title (B 12) with stratego (Greek [x]), rather than as the personal name of the Apracaraja's brother (as B). Compare the similar use of [x] = baga in the Surkh Kotal Bactrian inscription, line 1: [x], and Henning's remarks thereon in BSOAS 23, 1960, 51 and 52, note 5.

viyayamitro ya: This (and not vaga) is the personal name of the Commander, the king's brother. It is a variant spelling of the name Vijayamitra/ Viyakamitra of the Bajaur casket inscriptions (below, part II); intervocalic -j- frequently becomes -y- in the Kharosthi dialect. The nominative termination here, and in stratego, is surprising. Most of the nominative singular masculine nouns in this inscription end in -e, and Kharosthi texts usually have nominatives in either -e or -o, but not both. But the readings are clear (though B has stratega). B reads viyayamiroya, with "the suffix -oya-" of "a derivative feminine noun" (B 12), as the name of the following "aunt" of the king; but this would violate the pattern, consistent throughout the inscription, of giving the term of relation first, then the personal name. The name is Viyayamitra, masculine, applying to the foregoing "brother." maduka: Sanskrit matrka, 'mother,' not 'maternal aunt' (B 12).

sabhaedata: A proper name, of the king's mother according to the pattern noted above of names follow- ing relation terms. Cf. the other female names in the family, Vasavadata and (?) Mahaeda. (B'2 has "'re- vered' from older sabhdjaya- 'to honor', with secondary -d- for-y-.")

Line 6:

kida-padiharia: The construction here seems to require a past participle ( = pratihrta 'presented'), though the form is unusual; elision of intervocalic -t- is abnormal in Kharosthi (but cf. thiae?* sthitake in line 2; B 10). The form looks more like a gerund, but this would not fit the syntax. For the compound form, B (4) compares the type drsta-nasta. The h seems clear, though B reads b (padibaria < -bharita).

avi ya: = api ca; cf. note on a, line 2.

ahethimajimami: I prefer to take this as the proper name (probably after the name of its founder) of the relic shrine (pratithavana = pratisthapana), rather than as B's 'highest-central,' < ahethi 'not lowest' + majima < majjhima < madhyama, with unexplained deaspiration (4, 10), Ahethi- is more probably related to Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit ahethaka 'non-injurious (person)' (Franklin Edgerton, Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit Dictionary, 86b).

pratitha(vita): The last two aksaras look like -thisa, but the context rules this out.

Line 7:

vasia: This must be = varsa, or rather varsika, though the usual Kharosthi form is vasa; rather than B's <di>-vasi'a 'day' (3, 10). varsa is used in the sense of regnal year' as distinct from samvatsara 'year of an era', as in the Takht-i-bahi inscription (K 62): maha-rayasa Guduvharasa vas[*e] 20 4 1 1 1 sa[m]ba [tsarae ti]satimae 1 100 1 1 1 .... The regnal year here is presumably that of the Apracaraja.

II. The Apracarajas of Bajaur

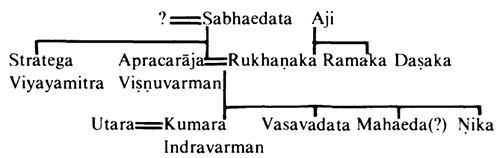

The dynasty of rulers of the 1st century B.C. and 1st century A.D. bearing the titles apracaraja and stratega is known from the Bajaur (Shinkot) casket inscriptions (see note 1), and from the coins of three members of the family, Aspavarman, Indravarman, and Sasa. These kings were the hereditary rulers of the region now known as Bajaur, situated along the western border of Pakistan's Northwest Frontier Province, to the west of Swat. The new Kharosthi inscription vastly increases our knowledge of this dynasty. The co-dedication of the relics by the prince together with various family members enables us to reconstruct a family line, not only of the kings themselves, but of their brothers, wives, and other relatives; a body of information much like that derived for the early Mathura Ksatrapas from the co-dedications of the Lion-capital inscriptions (see the diagram in K 47). The family tree of the Apracarajas is derived from the new inscription as follows:4

[i]Sabhaedata Aji Stratega Viyayamitra Apracaraja Visnuvarman Rukhanaka Ramaka Dasaka Utara Kumara Indravarman Vasavadata Mahaeda(?) Nika

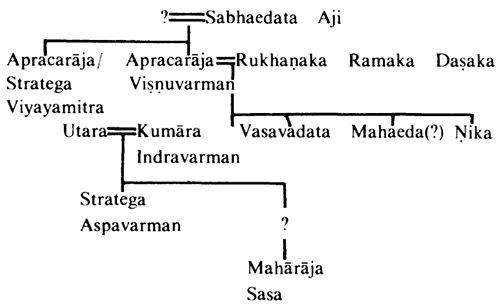

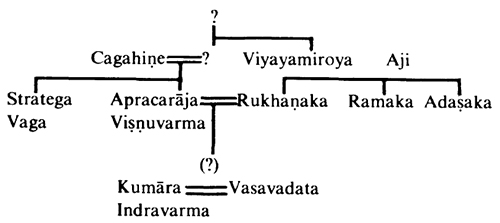

This tree may be further developed with the genealogical information obtained from the other epigraphic and numismatic material mentioned above:

? = Sabhaedata Aji Apracaraja/ Stratega Viyayamitra Apracaraja Visnuvarman = Rukhanaka Ramaka Dasaka Utara = Kumara Indravarman Vasavadata Mahaeda(?) Nika Stratega Aspavarman ? Maharaja Sasa

The additional title apracaraja for Viyayamitra, who is stratega in the new inscription, is derived from the Bajaur inscription. As this is the other major source for the history of the Bajaur kings, and as it both clarifies and is clarified by the new inscription, it will be helpful here to summarize its contents and the controversies about it.

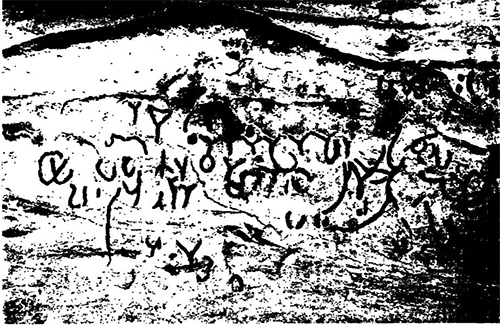

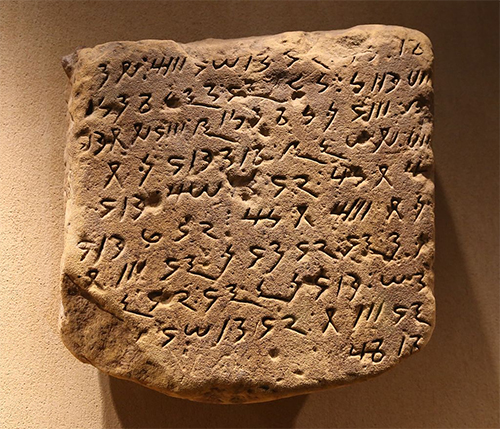

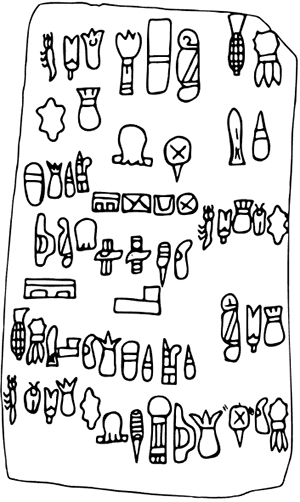

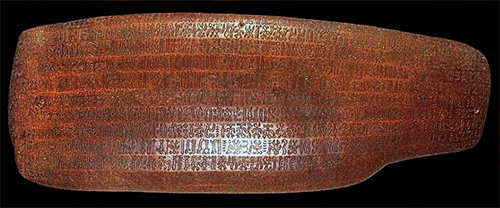

The casket bears five separate short passages (A through E) in Kharosthi script, of which two are fragmentary. These are divided into two groups, the second group having been added to the previously inscribed casket at a considerably later date.5 The earlier group consists of the three fragmentary lines of A written on the lid of the casket, which apparently contained a date (the number is broken off) in the reign of minedrasa maharajasa, i.e., the famous indo-Greek king Menander, the Milinda of Buddhist texts, who ruled in the second century B.C. The later group comprises inscriptions C-E, which record the re-dedication of the casket, which had been damaged and neglected, by vijayamitrena apracarajena (D-3). The same name occurs also in C-1, vijaya[mitre]na.... (Inscription C is on the lid of the casket, which is broken. The remaining inscriptions are on the body of the casket and are complete.)

The remaining inscription, B, is the subject of a controversy which is crucial to the understanding of the history of the Bajaur kings -- and which, I believe, can now be solved with the aid of the new inscription. B is written on the inside of the casket, between lines 1 and 2 of inscription D, and reads viyakamitrasa apracarajasa. This inscription was attributed by the first editor, N. G. Majumdar, to the earlier group, and interpreted as meaning that the casket was originally dedicated as "(The gift) of Viyakamitra, who has no king as his adversary" (EI 24, 7). Konow, however, has convincingly argued that it belongs to the later group of inscriptions, and was added on as a postscript or afterthought to the regnal year given in D-2, vasaye pamcamaye 4 1.

Konow's position finds its strongest support in the paleographic argument. The form of the two s-s in inscription B are of the open-sided variety which is seen in the later inscriptions C-E, and which is characteristic of later stages of the Kharosthi script; while s in inscription A has the earlier closed form. It is true, as Majumdar points out (2) that the end of line D-2 seems to have been curved downward toward the center of the bowl to avoid inscription B, which must therefore (according to Majumdar) have been written before D. But one could just as well argue that line D-2 was inscribed (with the characteristic and notorious casual style of Kharosthi scribes) out of the proper line; and that the scribe who added B later took advantage of the resulting extra space between lines D-1 and 2. Konow's paleographic analysis, utilizing the highly reliable test of the forms of Kharosthi s, is certainly stronger than Majumdar's argument based on inconclusive assumptions about the arrangement of the lines.

The argument over the attribution of inscription B to the earlier or later groups, trivial as it may seem, has important historical consequences. If one goes with Majumdar (and D. C. Sircar), putting B in the earlier group, it appears that there was an early Apracaraja named Viyakamitra, who ruled as a subordinate to the Greek emperor Menander (since he dated his inscription by the latter's rule) in the second century B.C. This Viyakamitra is then presumed to be the father or grandfather (Sircar, SI 103, note 1) of the later Apracaraja Vijayamitra of inscriptions C and D.

If, on the other hand, one accepts Konow's view and places B with the later group, then there is no longer any question of an Apracaraja in Menander's time. Rather, there are the names Viyakamitra (B) and Vijayamitra (C-1, D-3), both bearing the title Apracaraja, at the time of the later inscriptions (estimated by Konow as dating from about the middle of the first century B.C.). But, as Konow (NIA 2, 1939-40, 642) observes, "it would be absurd to assume the existence of two contemporaneous kings, Viyakamitra and Vijayamitra, both using the epithet apracaraja." He therefore concludes that the two names are actually merely orthographic variants, and refer to the same person. The different spellings of one name in the same document can be explained on the grounds that, as previously mentioned, the inscription B which contains the deviant form Viyakamitra is an addition -- a marginal gloss, so to speak -- in a different hand, intended to clarify that the regnal date in D-2 is that of Vijaya-/ Viyakamitra.

This ingenious suggestion is justified by Konow on the basis of similar orthographic and/or phonetic variations in Kharosthi. j/y is well-known; for instance, Aja and Aya for the name of King Azes (as he is called in Greek). k for y (if Vijaya- is in fact the original or proper form of the name, which is not absolutely certain) is more difficult, but Konow does cite such examples as udaka for udaya in Kharosthi manuscripts.

The crux of the question of the placement of inscription B of the Bajaur casket, and of the historical consequences thereof, thus rests of the validity of Konow's identification of Vijayamitra = Viyakamitra.

It is here that the new inscription comes to our aid, for the name Viyayamitra therein (line 5) presents a third variant, an intermediate form, of what can only be the same name. Both of the intervocalic consonants -j- and -y- were subject to phonetic change in northwestern Prakrit; -j- to -y- (as above; also K xcix-c), and -y- to a palatal fricative for which Kharosthi has no sign proper, but which may be written as -y-, -k-, or -g(r)- (K cv-cvi). We have, in other words, in the three forms Vijaya-/Viyaka-/Viyayamitra of the two inscriptions different representations of the same name; the first form preserving the Sanskrit orthography, the others being different attempts to represent the actual colloquial pronunciation ( Viyaya), which cannot be adequately rendered in an Indic script which characteristically lacks symbols for spirants.

If it may be considered settled that there was only one Apracaraja in the Bajaur inscriptions, those inscriptions can now be dated by their relation to the new inscription through the identification of Vijaya-/ Viyakamitra of the former with Viyayamitra of the latter. It may be assumed that the Bajaur casket is the older of the two inscriptions, both on the grounds of its connection with inscriptions as old as the time of Menander, and of chronological data to be examined later (see note 8). Vijayamitra must have been elevated, between the time of the two inscriptions, from Apracaraja, or local king, to Stratega, or commander, under the emperor Azes 11. (This too will be explained in detail below.) At the time of the new inscription, Vijayamitra's successor as Apracaraja, Visnuvarman, was in his 25th regnal year, which corresponds to 5 A.D. Thus he became Apracaraja in 20 B.C.; so the later Bajaur inscription, in which Vijayamitra is still Apracaraja, must be sometime, but probably not too many years, before 20 B.C. It may be dated to c. 30-20 B.C.6

This date is not far off from Konow's original estimate on paleographic grounds of "the middle of the first century B.C." (NIA 2, 1939-40, 641) for the later inscriptions on the Bajaur casket. Moreover, his citation of their "rather close agreement with the palaeography of the Mathura Lion Capital" (ibid.), which is dated at c. 10 A.D. by Sircar (AIU 133), would tend to move the date up somewhat toward the range now established by the synchronization with the new inscription. Finally, the new data also endorse Konow's estimate that the younger Bajaur group "must be about a century later" (NIA 2, 644) than the earlier inscriptions of the time of Menander.

The later members of the Bajaur line as given in the second family tree are clearly attested by coins. Aspacarman is well-known from coins issued jointly with the kings Azes [11] and Gondophernes with the Kharosthi legend indravarmaputrasa aspavarmasa strategasa javatasa, "(Coin) of Aspavarman, victorious commander, son of Indravarman" (R. B. Whitehead, NC, 6th series, 4, 1944, 99-101). Sasa is known from coins (cf. note 6) with the legend maharajasa aspabhratapu-trasa tratarasa sasasa," (Coin) of Maharaja Sasa, savior, nephew of Aspa" (ibid. 101). Aspa here is almost certainly Aspavarman; the name of his brother, Sasa's father, is unknown.

The history of the Bajaur dynasty of Apracarajas can now be reconstructed in some detail from the data of the two inscriptions and the coins. They first appear in history at the time of the fifth regnal year of Vijayamitra as Apracaraja, c. 30-20 B.C., in the later inscriptions on the Shinkot casket. There is no indication in this document that they were subordinated to the greater Scytho-Parthian dynasty centered in Taxila, under the emperor Azes II or Azilises; but there may well have been some such association even at this early period. The old theory that Viyakamitra was the father or grandfather of Vijayamitra and a feudatory of Menander must now be discarded. The Bajaur kings had no connections with the Greeks, other than their re-dedication of the Shinkot casket of Menander's time.

Then, at least 25 years later, in the new "Avaca" inscription of 5 A.D., we find Vijayamitra serving as stratega to an unspecified emperor, either Azilises or more likely Azes II,[7] while his younger brother,[8] the previously unknown Visnuvarman, is now apracaraja, and the latter's son Indravarman is kumara or heir-apparent.[9] The fact that Vijayamitra has been elevated from apracaraja to stratega indicates that the latter office was the senior position, while the post of apracaraja, or local ruler, was the junior position occupied by the younger brother or son of the stratega.

From coins of presumably a slightly later date we next find Indravarman ruling as apracaraja. He must have succeeded his father Visnuvarman in that position, apparently (see note 9) while Vijayamitra was still stratega to the Indo-Scythian emperor.

It is not known whether Indravarman ever ruled as stratega; nor can it be said who succeeded him as apracaraja. His son Aspavarman was stratega to Azes II not long after the time of the new inscription (5 A.D.), since Azes II ceased to rule in c. 20 A.D. This indicates that Indravarman's rule must have been fairly short.

Aspavarman continued to serve as stratega under Gondophernes, who succeeded Azes II. Finally, Aspavarman's nephew Sasa ruled as maharaja in conjunction (NC 1944, 101) with the same emperor. At this point probably in the second quarter of the first century A.D. the line of the Bajaur kings fades from history.

III. The Origin of the Vikrama Era

By way of background for the discussion of the importance of the new "Avaca" inscription for the problem of the origin of the "Vikrama Samvat" of 58 B.C., a brief summary of the epigraphic data and the views of various scholars on the subject is given below.[10]

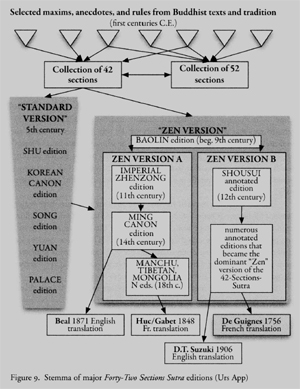

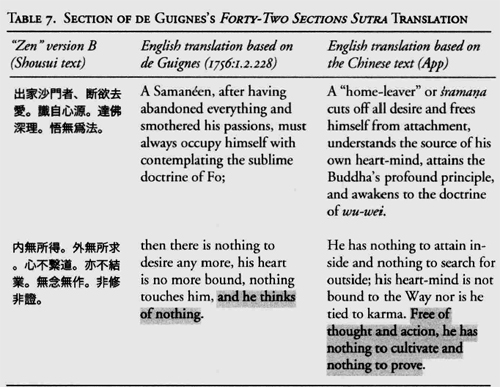

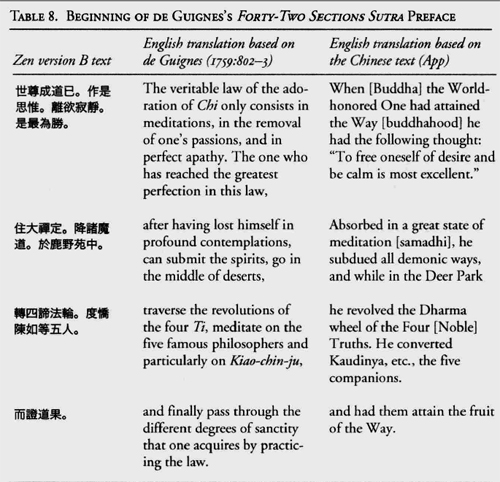

1. Epigraphic data: The range of inscriptional dates which belong to, or are believed to belong to[11] the era of 58 B.C., are listed below, grouped according to the several different names or titles applied at different historical periods to the era.[12]

a. Inscriptions dated in the years of Aya or Aja: 134 (Kalawan) and 136 (Taxila silver scroll). To these must now be added, of course, the new inscription of the year 63.

b. Inscriptions dated in Krta years: 282 (Nandsa) through 481 (Nagari).

c. Inscriptions dated in Malava years: 461 (Mandasor) through 936 (Gyaraspur). (In the last inscription in b and the first in c, the date is designated with both terms Krta and Malava. The combination of the two names in this period suggests a transitional stage.

d. Inscriptions dated in Vikrama or Vikramaditya years: 898 (Dholpur),[13] and many inscriptions thereafter.

In addition, from the fifth century A.D. on, many dates in this era are denoted by neutral terms for "year," especially samvat, and also sasvatsara, varsa, etc. 2.

Opinions on the origin of the Vikrama era: The following are only the most authoritative or widely held views on the problem. The list is not meant to be comprehensive.

a. The traditionalist view is that the era was founded by an Indian king Vikramaditya, identified with either the geographical region of Malwa (Malava), or the tribal republic (gana) Malava. According to this view, which finds its main support in the Jaina historical text Kalakacaryakathanaka and in popular traditions, Vikramaditya drove the Sakas (Scythians) from Uj-jayini (Ujjain) and founded the era which bears his name in celebration of this triumph.

This view has been espoused by, among others, R. B. Pandey (Proceedings of the All-India Oriental Conference, Benares, 1943-4, 503-9); Harihar Nivas Dvivedi (VV 131-2); and R. C. Majumdar (VV 302). It also appears to find some support from Konow (JRAS 1932, 953, 955).

The objections to this tradionalist view are serious. First, there is no epigraphic or numismatic evidence for any king called Vikramaditya in the first century B.C. Second, and more cogently, the theory fails to explain why, if Vikramaditya founded the era in 58 B.C., his name is never applied to it until at least eight and a half centuries later (see note 13).

b. F. W. Thomas (JRA S 1914, 414) and K. P. Jayaswal (JBORS 16, 1936, 251) believe that the era was founded by the Malava gana to celebrate their "tribal independence" (Thomas) or their overthrow of the Sakas (Jayaswal). According to Jayaswal, the Vikramaditya for whom the era was (later) named was the Satavahana king Gautamiputra Satakarni, who he says also took part in the expulsion of the Sakas.

The objections to this theory are essentially the same as to the preceding one. The events described are not corroborated by any firm archaeological evidence, and the name Malava, invoked to explain the origin of the era, was not actually applied to it until over 500 years later.

c. A. S. Altekar (VV 16-9) attributes the foundation of the Vikrama era to a "king, general, or president" of the Malava tribe named Krta.

Here again, the name Krta for the era in question does not occur until over three centuries after its foundation; and the existence of such a historical figure is, as Altekar himself cautiously admits (19), purely speculative.

d. D. R. Bhandarkar (VV 57-69) suggests that the era may have been established by the Sunga king Pusyamitra who, in overthrowing the Buddhists and re-establishing orthodox Brahmanism set up, as it were, a new krtayuga, or golden age.

This theory has little to support it and has not won any significant support.

e. J. F. Fleet (JRAS 1905, 232-3) was of the opinion that the Vikrama era "was certainly founded . . . by Kaniska." Subsequent epigraphic and archaeological discoveries have conclusively disproven this view.

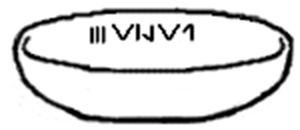

f. The theory that the Scytho-Parthian king Azes I was the originator of the Vikrama era of 58 B.C. was first proposed by Sir John Marshall (JRAS 1914, 977) in reference to the Taxila silver scroll, which is dated in the year 136 "ayasa." Marshall interpreted that word as meaning 'of Azes,' Aya being the Prakrit form of the name, as it also appears in the Kharosthi legends of his coins. This interpretation was at first disputed by Konow (K 71-3), but was confirmed by the subsequent discovery of the Kalawan inscription dated in the year 134 "ajasa," obviously a mere graphic variant of ayasa, 'of Azes.'

On the west side of the tank the Stupa K1 is also worthy of notice. Observe in particular the seated image of the Buddha in the niche on the northern side, and also the cornice and other details of a distinctively Hellenistic character.

On to the north side of this stupa were subsequently built several small chambers, probably chapels, facing north. They stand on a common base adorned with a row of stunted pilasters alternating with niches of the same design as those above the terrace of the Main Stupa, namely, trefoil arches and doorways with sloping jambs in which figures of the Buddha were placed.

From this point it is well worth while to ascend the higher ground to the north and take a bird's-eye view of the whole site and of the surrounding country (PI. IX). Five years ago the ground level of the whole excavated area was little lower than this elevated plateau, and standing on the edge of the latter we get a good idea of the amount of debris that had to be shifted before this array of buildings could be exposed to view. The point to which this debris rose around the Great Stupa itself is still clearly visible on the sides of the structure.

As to the character of the remains that still lie buried beneath the plateau on which we are standing, a clear indication is afforded by other Buddhist sites in the neighbourhood. If the visitor will look at the other eminences in the valley, he will see that many of them are crowned by groups of ancient ruins, and he will observe that in each group there is a circular mound standing side by side with a square one. In each of these eases the circular mound covers the remains of a Buddhist stupa, and the square one adjoining it the remains of a monastery. Similarly, at the Dharmarajika Stupa, which was the chief monument of its kind at Taxila, it may be taken for granted that quarters were provided for the monks in close proximity to the sacred edifice, and it is obvious from the configuration of the ground that these quarters must have occupied the northern part of the site. To this monastery no doubt belong the high and massive walls which have been laid bare on the eastern side of the plateau, but judging by the results obtained from other trial trenches it is doubtful if this area would repay excavation.

Descending again to the lower level we pass, on our right hand, the shrine H1 which was probably intended for an image of the Dying Buddha. This building exhibits three types of masonry, representing three different periods of construction. In the original shrine the stonework is of the small diaper pattern, but subsequently this shrine was strengthened and enlarged by the addition of a contiguous wall in the larger diaper style, as well as of a second wall enclosing a pradakshina passage and portico in front. Later on, when the level had risen several feet, additions in semi-ashlar masonry were made, and other repairs were carried out at a still later date. The only minor antiquities of interest in this building were 28 debased silver coins of the Greek king Zoilus (PI. III, 14). They were brought to light beneath the foundation of the earliest chapel, where they appear to have been deposited before the site was occupied by the Buddhists.

The two small pits M4 are of interest only as affording some evidence as to the age when the Gandhara School of Art was flourishing. They were used for the mixing of lime stucco and their floors were composed of Gandhara reliefs laid face downwards. As the reliefs in question were already in a sadly worn and damaged condition before they were let into the floor, it may safely be inferred that a considerable period—say a century or more—had elapsed between the time when they were carved and the construction of the pits. But from the character of their walls the latter appear to have been constructed in the 3rd or 4th century A.D. and it follows, therefore, that the reliefs cannot be assigned to a later date than the 2nd or 3rd century A.D. Evidence of a precisely similar character was also obtained from the chamber B17 on the eastern side of the Great Stupa.

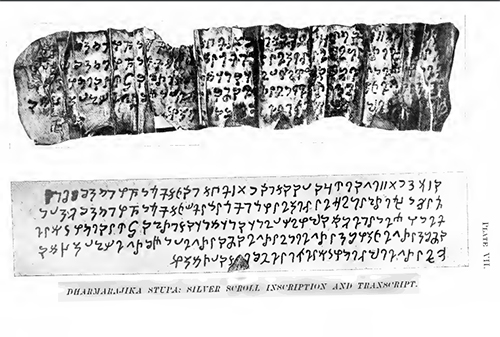

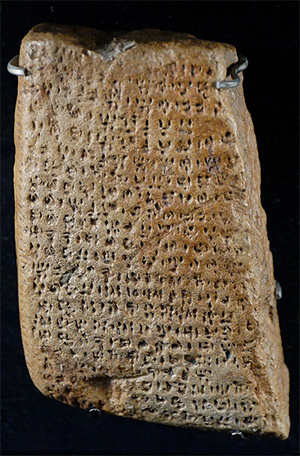

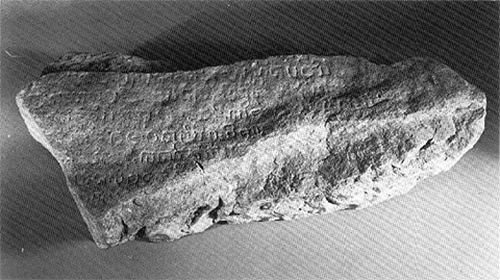

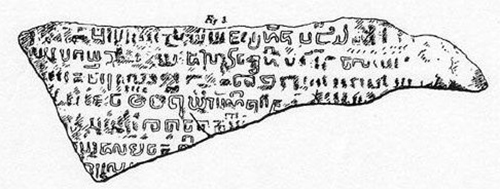

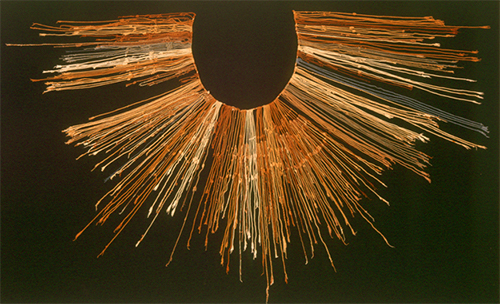

The complex of chambers G1 to G8 comprises chapels erected at different periods and in different styles of masonry. From an architectural point of view they are in no way remarkable, but the chapel G5 merits notice, because it was here that one of the most interesting relics yet discovered in India was unearthed. The find was made near the back wall of the chapel opposite the Main Stupa and about a foot below the original floor. It consisted of a steatite vessel with a silver vase inside, and in the vase an inscribed scroll and a small gold casket containing some minute bone relics. A heavy stone placed over the deposit had, unfortunately, been crushed down by the fall of the roof, and had broken both the steatite vessel and the silver vase, but had left the gold casket uninjured, and had chipped only a few fragments from the edge of the scroll, nearly all of which were fortunately recovered (Pl. VII). The inscription, which is in the Kharoshthi character and dated in the year 136 (circa 78 A.D.), records that the relics were those of the Lord Buddha himself. It reads as follows:

L. 1. Sa 100. 20. 10. 4. 1. 1. Ayasa Ashadasa masasa divase 10. 4. 1., isa divase pradistavita Bhagavato dhatu[o] Ura[sa]—

L. 2. kena Lotaphria-putrana Bahaliena Noachae nagare vastavena tena imc pradistavita Bhagavato dhatuo Dhamara—

L. 3. ie Tachhasie Tanuvae Bodhisatvagahami maha-rajasa rajatirajasa devaputrasa Khushanasa aroga-dachhinae

L. 4. sarva-buddhana puyae prachaja-hudhana puyae araha[ta*]na puyae sarvasa [tva*] na puyae mata-pitu puyae mitra-macha-nati-sa—

L. 5. lohi[ta*]na puyae atmano arogadachhinae nianae hotu [a], de samaparichago.

PLATE VII. DHARMARAJIKA STUPA: SILVER SCROLL INSCRIPTION AND TRANSCRIPT.

"In the year 136 of Azes, on the 15th day of the month of Ashadha, on this day relics of the Holy One (Buddha) were enshrined by Urasakes(?), son of Lotaphria, a man of Balkh, resident at the town of Noacha. By him these relics of the Holy One were enshrined in the Bodhisattva chapel at the Dharmarajika stupa in the district of Tanuva at Takshasila, for the bestowal of perfect health upon the great king, king of kings, the divine Kushana; for the veneration of all Buddhas; for the veneration of the private Buddhas; for the veneration of arhats; for the veneration of all sentient beings; for the veneration of (his) parents; for the veneration of (his) friends, advisers, kinsmen, and blood-relations, for the bestowal of perfect health upon himself. May this gift be ...........".[1]

-- A Guide to Taxila, by Sir John Marshal, KT., C.I.E., M.A., Ltt.D., F.S.A., Hon.A.R.I.B.A., ETC., Director General of Archaeology in India, 1918

This view has earned qualified support from such historians as Vincent Smith (Early History of India, 4th ed., Oxford, 1967, 244) and E. J. Rapson (Cambridge History of India 1, Cambridge 1922, 571, 581-2 515, 524-5 of the New Delhi reprint edition, 1968). It has been more recently (and more enthusiastically) upheld by A. D. N. Bivar (BSOAS 39, 1976, 335-6). On the whole, the theory that Azes I founded the era which later came to be known as the Vikrama Samvat is the one most widely held by modern scholars. They are not without reservations, as mentioned above, and below in g; but these reservations can now be eliminated by the new "Avaca" inscription.

g. Finally, there are some modern scholars -- notably H. C. Raychaudhuri (Political History of Ancient India, 7th ed., Calcutta 1972, 390 note 1) and D. C. Sircar (AIU 124-5, 127, and Indian Epigraphy, Delhi 1965, 256-7) -- who identify Aya/Aja of the Taxila and Kalawan inscriptions as Azes II, mentioned as the reigning king, and not as the founder of the era. (Konow, cited above as a "traditionalist," seems to agree with this view in JRAS 1932, 953: "The addition ayasa, ajasa need not ... be taken to characterize the era as founded by Azes.") Sircar suggests that the Indo-Parthian king Vonones may have founded the era of 58 B.C.

The view that Azes was the reigning, rather than the founding king of the era of the Kharosthi inscriptions is now ruled out by the evidence of the new inscription.

To review the situation as it now stands: the most probable candidate for founder of the Vikrama era is the Indo-Scythian king Azes I, whose name appears in connection with the earliest inscriptional dates which are attributable to that era. All available chronological data from numismatic and epigraphic material support a date for the beginning of the reign of Azes I around the middle of the first century B.C. Vincent Smith first proposed a succession of Scytho-Parthian kings on the basis of their coin types as Azes I - Azilises - Azes II, followed by Gondophernes. This succession was confirmed by Marshall's excavations at Taxila, and is now widely accepted. Now, the only fixed chronological point in this whole period of history comes (as is so often the case in ancient Indian history) from a correlation with a historical event outside of South Asia. I refer, of course, to the well-known description in the apocryphal Gospel of Thomas of that apostle's journey to India in the time of King Gunaphar, who can be none other than the Parthian king Gondophernes. That king must therefore have been ruling toward the middle of the first century A.D. It is thus apriori not unlikely that Azes, who preceded Gondophernes by three reigns, might have begun ruling about a century earlier.

Fortunately, we have more specific chronological data for Gondophernes, which supports the hypothesis presented above. The Takht-i-bahi inscription (K 57-62) is dated in the (unspecified) year (sambatsara) 103 and the regnal year 26 of Gondophernes. The unstated era is generally agreed to be the era of 58-7 B.C. (regardless of the question of its founder), so that the date of the inscription works out to 46 A.D. This year being the 26th of Gondophernes' rule, he began to rule in 20 A.D. If Azes I began his reign in 58 B.C., this leaves a period of 78 years for the three reigns of Azes I and his two successors, Azilises and Azes II, or an average reign of 26 years each; not an improbable figure, in view of the fact that Gondophernes himself ruled for, at the very least, 26 years, and of the general longevity of the Indo-Scythian rulers.[14]

On these epigraphic and historical grounds, then, Azes I is the most likely founder of the Vikrama era. He must have ruled in the first century B.C., and his name is associated with the earliest dates of what is generally agreed to be the "Vikrama" era of 58 B.C. The main reservation until now has been about the nature of that association; does it or does it not designate Azes as the founder of the era? The new inscription which is the subject of this paper answers this question, beyond the slightest doubt, in the affirmative. Not only does it give the earliest date by far, 63, with a specification of the era, but it explicitly attributes it to "the late Maharaja Azes" (maharayasa ayasa atidasa = maharajasya Ayasya atitasva[15]). This phrase can only mean that a dating system originating with the regnal years of Azes I was continued after his death, and thus (after the usual pattern of ancient Indian chronological systems) became, in effect, an era. At first, dates were specified as derived from the "late maharaja"; later on, as in the Kalawan and Taxila dates, the name itself of the king became in effect identical with the era, and the qualifying titles were dropped. (This explains the problem of why Azes' name was mentioned without any title in the latter two inscriptions, this being the main reason that Konow was originally reluctant to take ayasa as the name of a king.) Thus it can no longer be held that Azes of the Kalawan and Taxila inscriptions was the current ruler (i.e., Azes II).

It is now beyond question, from the data of the new inscription, that Azes I "founded" an era, in the sense that his regnal dates were continued after his death as the basis of a chronological system. That this era is identical with that of the Kalawan and Taxila inscriptions of the years 134 and 136 is equally certain. The only remaining problem is whether these dates are in fact in the same era of 58 B.C. which, much later in history, came to be known as the Vikrama era. This has long been held probable, though it must be ad-mitted that there is still no absolute proof of it. Thus, for instance, Marshall himself, who first proposed the now proven theory that Azes was the founder of this earlier Scytho-Parthian era, stipulated that "the identity of the era of Azes and the Vikrama era can hardly be regarded as fully established. . . . It is quite possible that the era of Azes will be found to have commenced a few years earlier or later than 58 B.C." (JRAS 1914, 977).

As it happens, no such evidence to differentiate Azes' era from the Vikrama era has turned up; so that, although absolute proof has not been found either, the weight of probability remains heavily in favor of the identity of the two eras. We have, on the one hand, an era founded by Azes I, with dates up to 136, which must have begun around the middle of the first century B.C. On the other hand, we have an era beginning in 58 B.C., which is known from inscriptions with dates from 288 up to modern times under various names Krta, Malava, and Vikrama. Two interpretations are possible: either (1) that there were two eras of almost the same date, one of which died out in its second century, and the other of which is not attested until the 288th year of its use; or (2) that the two are the same era, and that the change of name from ava(sa) or "Azes' ", to Krta was merely the first of several such changes which the era was to undergo. I feel there can be no question that the second alternative is far more likely,[16] and that therefore the longstanding problem of the origin of the Vikrama era can now be considered solved: Azes I was the founder of the Vikrama era.

One problem concerning the historical development of the Vikrama era remains. This is the question of the origin and meaning of the term krta applied in the 3rd to 5th centuries to the Vikrama era. Various suggestions have been offered for the explanation of krta (among them Altekar's theory cited above in section III. 2 c), but, as Sircar concludes, "the real significance of this name is yet unknown."[17] The origin and development of the later names of the era, Malava and, of course, Vikram(aditya), have been fully explained by Sircar.[18]

POSTSCRIPT:

While this article was in the press, the same inscription was edited and discussed by Dr. B. N. Mukherjee in "An Interesting Kharosthi Inscription" (Journal of Ancient Indian History 11, 1978, 93-114). It was therefore not possible to refer to Dr. Mukherjee's version in this paper. While we have agreed as to the overall historical significance of the inscription, the reader will notice several differences in specific points of textual and historical interpretation.

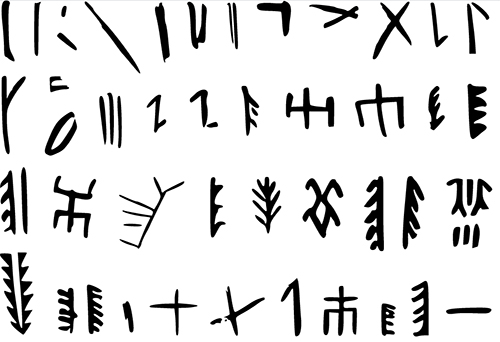

was mani or Mannus, the progenitor of humanity, which once more forms a special section in the

was mani or Mannus, the progenitor of humanity, which once more forms a special section in the  for Mannus or Mene, the spiritual Moon (Psychomena).

for Mannus or Mene, the spiritual Moon (Psychomena). is Tyr, Zio, also Zeizzo or Erich, the one-armed sword-god, the "generator." His hieroglyph also consists of the sign of Ur

is Tyr, Zio, also Zeizzo or Erich, the one-armed sword-god, the "generator." His hieroglyph also consists of the sign of Ur  and the Tyr-rune

and the Tyr-rune  , which symbolizes the solar ray, the solar arrow as impregnator (phallus). His sword, his one-arm, his phallus erectus, clearly designates him as the provider of increase, the multiplier or generator under whose guardianship marriages stood, but war as well, since war increased property through the taking of booty and drove out vermin. The fourth, Mercury

, which symbolizes the solar ray, the solar arrow as impregnator (phallus). His sword, his one-arm, his phallus erectus, clearly designates him as the provider of increase, the multiplier or generator under whose guardianship marriages stood, but war as well, since war increased property through the taking of booty and drove out vermin. The fourth, Mercury  , is Wuotan, whose rune (othil

, is Wuotan, whose rune (othil  ) is in this instance reversed

) is in this instance reversed  and connected to the sign of increase

and connected to the sign of increase  to form

to form  , indicating the increaser, bringer of luck, the wish-god.

, indicating the increaser, bringer of luck, the wish-god.  , and means primeval generation, or "the one who generates things out of the Ur"

, and means primeval generation, or "the one who generates things out of the Ur"