Part 1 of 4

The India Office Library: Its History, Resources, and Functionsby Rajeshwari Datta

The Library Quarterly

Mar 31, 1966

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHTYOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ

THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

I. History

A. IntroductionThe India Office Library has been in existence since 1798, when the Court of Directors of the East India Company passed a resolution to devote a portion of their famous India House in Leadenhall Street, London, to the establishment of a library and museum.

Much research on the history, literature, arts, and antiquities of India, as well as scientific investigation and exploration of the country, had been going on for a considerable number of years, carried out for the most part by servants of the Company. Many valuable collections of literary, artistic, scientific, and commercial interest had been formed by them, and a permanent repository for the safe preservation and use of such material was becoming an urgent need.

This research and study had been given special encouragement under Warren Hastings, governor of Bengal from 1772 to 1785. By that time England had begun to establish herself politically as a strong ruling power in India.

To conduct administration with any degree of efficiency, it was necessary to be acquainted with the laws and institutions of the country, its geography and history; and, if commerce was to be furthered, a knowledge of its resources was required. Thus it became the policy of the East India Company to promote and encourage the study of Sanskrit, Arabic, and Persian literature, which was the main source of knowledge of the country's organization, and to conduct scientific surveys throughout its territories. Some of the first administrators, judges, and other officials of the Company were, therefore, also the first great orientalists and oriental linguists -- to name only a few, Sir Charles Wilkins, first librarian to the Company, Sir William Jones, H. T. Colebrooke, and Horace Hayman Wilson, also one of the Company's librarians.B. Sir Charles Wilkins and the Foundation of the LibraryWilkins went out to Bengal in 1770 and had "the courage and genius to commence and successfully prosecute the study of the Sanskrit language which was up to that time, not merely unknown but supposed to be unattainable by Europeans."1 [Gentleman's Magazine, N.S., VI (1837), 97.] He was thus the first European to learn Sanskrit and disclose the vast field of Sanskrit literature to the West. As a member of the Bengal Civil Service of the East India Company, he had spent several years in India and established a high reputation for himself as a scholar of Sanskrit.

For inscriptions as for Sanskrit literary texts, Europeans in India often sought the help of pandits. More frequently than with texts, however, native knowledge was apt to fall short of their expectations, as ancient scripts proved a hurdle.2 [On the particular difficulty of consulting pandits for older forms of language (Vedic) or of script (in inscriptions), and objections raised by scholars in Europe, see Rocher and Rocher 2012: 25, 77, 105, 189.]

We are repeatedly told that "even pandits" were unable to decipher a script and interpret inscriptions.-- Indian Epigraphy and the Asiatic Society: The First Fifty Years, by Ludo Rocher and Rosane Rocher

An even more remarkable achievement by Wilkins was his translation, published as a letter in AR 1, 279-83, of the record now known as the Nagarjuni hill cave inscription of the early Maukhari king Anantavarman.9 [Presented March 17, 1785 (Chaudhuri, Proceedings, 47).] While his comment that the script is "very materially different from that we find in inscriptions of eighteen hundred years ago" is due to his incorrect dating of the Mungir plate alluded to earlier, he was nonetheless correct that "the character is undoubtedly the most ancient of any that have hitherto come under my inspection." (Anantavarman is now known to have ruled sometime in the sixth century A.D.)

It is truly remarkable that Wilkins was somehow able to read the late Brahmi of this period, which, unlike the scripts of three centuries later, is very different from modern scripts both in its general form and in many of its specific characters. It is thus not entirely clear how, beyond pure perseverance and genius, Wilkins managed to read this inscription, but presumably he did this by working back from the script of the Pala period which he had already mastered.10 [The precise order in which Wilkins translated his first three inss. is not certain, but it is clear that he worked on the Mungir ins. first, in 1781, and that the Nagarjuni and Badal inss. followed in the period between 1781 and his presentation of all three inss. to the society in 1785 (see Kejariwal, The Asiatic Society, 43-4).] In any case, his translation, while once again not always correct, proves beyond question that he could read the late Brahmi, or early Siddhamatrka, script of the sixth century.

-- Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the Other Indo-Aryan Languages, by Richard Salomon

His translation of the famous Bhagavat-Geeta into English was published by the Court of Directors in 1785 at their own expense, and the "literary men of Europe saw in this publication the day-spring of that splendid prospect, which has in part been realized by Sir William Jones, Colebrooke and others."2 [Ibid.] Wilkins was also the first to prepare with his own hands the first Bengali and Persian types for printing in Bengal. It was from his Bengali types that Nathaniel Brassey Halhed's Grammar of the Bengali Language was printed in 1778. These types were used for printing various Bengali and Persian texts for many years. With Sir Williams Jones he founded the Asiatic Society of Bengal in 1784, which had for its special object the promotion of the study of Asiatic languages, literature, history, and science. All these subjects were illustrated by the succession of essays and dissertations published in the society's journal, Asiatic Researches.

This activity opened a new era in the study of the linguistics, archeology, and history of the East. According to Robert Orme, the Company's historiographer, oriental scholars pursuing their researches in England began to feel the great need of a collection of manuscripts and printed books in that country "for affording that information on Indian affairs, the expense and labour of obtaining which was oppressive in the extreme when undertaken by private individuals."3 [Robert Orme, Historical Fragments of the Mogul Empire (London: F. Wingrave, 1805), pp. xxviii-xxix.] Orme often lamented the want of an Indian research collection in England and firmly believed that "a ship's cargo of oriental and valuable manuscripts might be collected in the settlements between Delhi and Cape Comorin."4 [Ibid.] Urged by him, John Roberts, a great friend of Orme's, who had been chairman and deputy-chairman of the Company on several occasions, prevailed upon the Court of Directors to take action. The result was a dispatch to the Bengal Government on May 25, 1798:

You will have observed by our Dispatches from time to time, that we have invariably manifested, as the occasion required, our disposition for the encouragement of Indian Literature. We understand it has been of years a frequent practice among our Servants, especially in Bengal, to make Collections of Oriental Manuscripts, many of which have afterwards been brought into this country, these remaining in private hands, and being likely in a course of time to pass into others, in which case probably no use can be made of them, they are in danger of being neglected, and at length in a great measure lost to Europe as well as to India. We think this issue a matter of greater regret, because we apprehend that since the decline of Mogul Empire, the encouragement formerly given in it to Persian Literature has ceased; that hardly any new Works of celebrity appear, and that few Copies of Books of established Character are now made; so that there being by the accidents of time, and the exportation of many of the best Manuscripts, a progressive diminution of the original stock, Hindostan may at length be much thinned of its literary Stores, without greatly enriching Europe. To prevent in part this injury to Letters, we have thought that the Institution of a Public Repository in this country for Oriental Writings, would be useful, and that a thing professedly of this kind is still a bibliothecal desideratum here. It is not our meaning that the Company should go into any considerable expense in forming a collection of Eastern Books, but we think the India House might with particular propriety be the centre of an ample accumulation of that nature; and conceiving also that Gentlemen might choose to lodge valuable Compositions, where they could be safely preserved and become useful to the Public, we therefore desire it to be made known that we are willing to allot a suitable Apartment for the purpose of an Oriental Repository, in the additional Buildings now erecting in Leadenhall Street; and that all Eastern manuscripts transmitted to that Repository will be carefully preserved and registered there.

By such a collection the literature of Persia and Mahomedan India may be preserved in this Country after, perhaps, it shall, from further changes, and the further declension of taste for it, be partly lost in its original Seats.

Now would we confine this Collection to Persian and Arabian Manuscripts. The Shanscrit writings, from the long subjection of the Hindoos to a Foreign Government, from the discouragements their Literature in consequence experienced, and from the ravages of time, must have suffered greatly. We should be glad, therefore that Copies of all the valuable Books which remain in that Language, or in any Language, or in any ancient Dialects of the Hindoos, might, through the Industry of individuals, at length be placed in safety in this Island, and form a part of the proposed Collection.5 [W. S. Seton-Karr (ed.), Selections from Calcutta Gazettes, Vol. III: 1798-1805 (Calcutta, 1868), pp. 16-17; see also Great Britain, India Office Records, Bengal Despatches (hereinafter cited as "Bengal Despatches"), XXXII, 430-39; also quoted in A. J. Arberry, The Library of the India Office (London, 1938), pp. 10-11.]

Wilkins, who had returned from India in 1786 because of ill health, but who continued to pursue his studies of Sanskrit literature, heard of this proposal and eagerly offered his services to arrange and supervise the collections to be formed. Naturally he was selected to be the first librarian and curator of the Oriental Library and Museum to be established at the India House. He drew up a detailed plan and submitted it to the Court of Directors. In his scheme the Library was given greater importance than the Museum, and he proposed that it should consist of both manuscripts and printed books:

The manuscripts to include works in all the languages of Asia; but particularly in the Persian, Arabic, and Sanskrita: and great care should be taken to make the collection very select, as well in correctness as subject. The Printed Books should consist generally of all such works as in any way relate to Oriental Subjects, including all that has been published upon the languages of the East, and every work which has appeared under the patronage of the Company. Maps, charts and views, with coins, medals, statues and inscriptions may be included under this head.6 [John Forbes Watson, On the Establishment in Connection with the India Museum and Library of an Indian Institute . . . (London, 1874), Appendix B, pp. 55-56.]

He further suggested that the Museum should comprise specimens of natural and artificial productions and miscellaneous articles, "chiefly presents, and generally such things as cannot conveniently be classed under any of the former heads."7 [Ibid.]

But matters proceeded in a leisurely manner, and it was only on February 18, 1801, that Wilkins was actually appointed librarian to the oriental repository at £200 per annum, a salary afterward raised by degrees to £1,000. This then marks the foundation of the Company's Library. At the end of the same year, the committee for superintending the Library met and resolved to collect all the books scattered through the different departments of the India House and the warehouses together with any articles of curiosity to be found there.8 [William Foster, The East India House (London: John Lane, 1924), p. 148.] By this time Orme had died, but he had bequeathed all his documents, books, manuscripts, and maps to William Roberts, with the express wish that they be transferred to the Library when established. The Orme collection was, therefore, the Library's first acquisition.

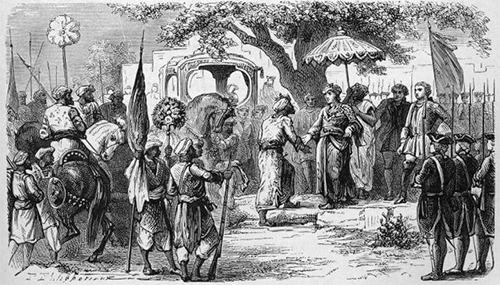

Shortly afterward the Library received some manuscripts from the library of Tippoo Sultan of Mysore, an inveterate enemy of the British, who had been defeated at Seringapatam in 1799. Following is an extract of the letter which the Company received from the army camp at Seringapatam on August 1, 1799:

A very copious and curious library has been found; the books are kept in chests, each having its particular wrapper, and they are generally in good preservation. I was there when a small part of them were looked into by Persian scholars, and saw some very richly adorned and illuminated, in style of the old Roman Catholic Missals found in monasteries. There must be thousands of volumes, and this library promises, on the whole, the greatest acquisitions ever gained to Europe of Oriental History and Literature. I hope it will be presented by the Army for public use.9 [Seton-Karr, op. cit., p. 241.]

The manuscripts were authenticated as either true copies or original documents by Habbeeb-oolla, Head Moonshee (or secretary) to the late Tippoo Sultan.

Not all of this exciting find, however, was transferred to London. At first only one document from this rich collection, called "The Manuscript Record of Tippoo Sultan's Dreams," was presented to the Company's Library by a Major Beatson. Later on, a selection of mainly Arabic and Persian manuscripts was sent for deposit and came to be known as the Tippoo Sultan Collection. The rest was housed in the College of Fort William in Calcutta until 1836, when it was moved to the library of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, with the exception of some oriental manuscripts, copies of which the society already possessed. These duplicates were later sent to the Library in London, where they are known as the Fort William Collection. A catalog of the whole of Tippoo Sultan's library was prepared by Captain Stewart (later Sir Charles Stewart), Assistant Persian Professor at Fort William College, and published in Cambridge in 1809. Some idea of the value of this collection can be had from the following editorial in the Calcutta Gazette of July 29, 1805, fannouncing Stewart's preparation of the catalog: "In the progress of his researches, he has discovered in that library a valuable work in the Persian language, referred to by Dow and Orme as necessary for the illustration of an important period in Eastern History, and which was sought for in India by those Historians without success. It is the History of the Emperor Aurungzebe, the 11th year of his reign to his death (an interval of forty years) written by a learned and authentic Mohammad Saki; being a continuation of Mahomed Kazim's History of the first ten years of that Prince."10 [Ibid., p. 491.]

Though various articles and objects and documents of interest began to pour in, the material growth of the Library was at first rather slow. There had been no response to the Court of Directors' letter of May 25, 1798, calling for the systematic collection of manuscripts. It accordingly dispatched a letter of remonstrance to the Bengal government, expressing disappointment over the lack of response and accusing the government of indifference. Continuing, the dispatch said:

We have now to inform you that the Apartments for the Oriental Library, being completed according to our intentions, have been placed under the Charge of Mr. Charles Wilkins, formerly of our Civil Service in Bengal, and that a considerable number of Manuscripts, and printed Books upon Oriental Subjects, with Objects of Natural History and Curiousity, have already been placed in it; among which are many valuable presents from Individuals and Public Bodies in this Country.

As our original views in establishing this Library have by no means been abandoned, and we still entertain hopes that the invitation held out to Individuals in India, in the above-mentioned paragraphs, would be successful, if properly seconded by our Supreme Government, we again refer you to them, and desire that the subject may be entered into with alacrity and zeal.

The new building in Leadenhall Street, being now prepared for the reception of books, coins, or other articles which may be presented for the oriental library and museums of the Hon'ble Court; the public are hereby informed that, whatever books in any of the Asiatic languages, or other articles coming within the object of the Hon'ble Court's collection, may be transmitted to the Secretary to the Government in the Public Department, for the purpose of being presented to the Hon'ble the Court of Directors, will be duly forwarded.11 [Hugh David Sandeman (ed.), Selections from Calcutta Gazettes, Vol. IV: 1806-1815 (Calcutta, 1868), pp. 26-27.]

In this letter the Court of Directors also asked that a complete catalog of Tippoo's manuscripts be prepared, which was probably why Stewart took up the work in 1805. It also sent instructions for all works already published in Calcutta which had any relation to the Company's affairs, as well as a copy of every future publication of a similar nature, to be sent for deposit in the Library. As for special works on the languages of India, it directed the government to send forty copies of each, to be used for instruction in the military seminary at Addiscombe.12 [Bengal Despatches, XLIII, 29-40; also quoted in Arberry, op. cit., p. 35.]

Soon thereafter, the Court of Directors also decided to reverse its initial policy of not going into "any considerable expense in forming a Collection of Eastern Books"13 [See above, p. 100.] and began to acquire valuable material, whenever available, by purchase. Thus in 1807 they bought from Richard Johnson, for the sum of Gns. 3,000, his large collection of oriental manuscripts. His collection of Indian and Persian miniature painting was bought from his widow a little later and has since become well known as the Johnson Collection.14 [Thomas L. Arnold, "The Johnson Collection in the India Office Library," Rupam, VI (April, 1921), 10-14.] Henceforth, the Library expanded rapidly through important donations and purchases. The Warren Hastings Collection was bought in 1809. Some of the most valuable contributions included Colebrooke's priceless collection of Sankrit manuscripts, the MacKenzie Collection in 1823, the Leyden manuscripts purchased in 1824, and the Hamilton Collection comprising survey accounts, natural history drawings, and other materials. Large sums for purchases were not easy to come by, so the stock of manuscripts was for the most part enriched by donations and bequests rather than by purchase.

The Museum part of the Library was also growing apace. Many interesting and curious pieces poured in until it was filled to overflowing with models showing customs and trades pursued in the East; weights and measures used in India; coins and models; modes of conveyance, including a fine collection of models of boats; musical instruments; a collection of idols-large and small-in silver, brass, copper, wood, and ivory; agricultural implements and products of the soil; animal products like raw silk, camel's hair, horn, and ivory; minerals; sculptures and works in stone; jewelry in gold and silver; textiles; arms and armors. Many of these objects were at first collected by civil servants of the Company during their official relations with the Indian courts or obtained as trophies of warfare. Later, Horsfield, a keen naturalist, who was appointed curator of the Museum in 1820, started to build up his extensive Natural History Collection. The Great Exhibitions of 1851 in London and 1855 in Paris also added many valuable specimens, of great interest to the general public.

One of the earliest objects of historical interest received in the museum was a piece of mechanism representing

a royal tyger in the act of devouring a prostrate European. There are some barrels, in imitation of an organ, within the body of the tyger, and a row of keys of natural notes. The sounds produced by the organ are intended to resemble the cries of a person in distress intermixed with a roar of a tyger. The machinery is so contrived, that while the organ is playing, the hand of the European is often lifted up to express his helpless and deplorable condition. The whole of this design was executed by the order of Tippoo Sultan who frequently amused himself with a sight of this emblematical triumph of the Khoodadaud [his dominions] over the English.15 ["Descriptions of Various Articles . . . to the Court of Directors of the East-India Company," Asiatic Annual Register for the Year 1800 (London, 1801), pp. 343-44.]

This toy was found in a room of the palace after the storming of Seringapatam and is now housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum in South Kensington. Other articles of Tippoo's, comprising his wardrobe; the golden Tiger's head, which formed part of his throne, made of wood and covered with plates of purest gold; his carpet; etc., were also received along with this famous tiger and now form part of the Indian section of the Victoria and Albert Museum.

In 1805 Wilkins, with an additional salary of £100, had been appointed "visitor for Oriental Literature" at a college founded by the Company for its civil service probationers at Hertford, which moved later to Haileybury and became known as Haileybury College, the famous center of oriental studies from which many renowned orientalists and civil servants of the Company emerged.16 [Memorials of Old Haileybury College (Westminster: Constable & Co., 1894), pp. 17-29.] In 1817, on the retire ment of the registrar of Indian Records, he was appointed superintendent of the Register Office, assisted by a clerk who was responsible for the actual care and management of the East India Company's records.17 [William Foster, Guide to India Office Records, 1600-1858 (hereinafter cited as "Guide") (London: Eyre & Spottiswoode, 1919), p. v.] During the same year the office of historiographer, which had been held by John Bruce, was abolished, and Wilkins, with an increased salary, was asked to take over the department with the staff of clerks formerely employed in the historiographer's office under his supervision.18 [Ibid.] Thus, though relieved of the charge of the Museum branch by Horsfield in 1820, his burden of responsibilities continued to increase. With inadequate staff at his disposal and the Library and the Museum growing to immense proportions, Wilkins felt the urgent necessity of formulating rules and regulations for admission and use of the Library by the public. The Library was thereafter open for inspection by visitors on Mondays, Thursdays, and Saturdays only (from ten to three), and tickets of admission printed on a particular form and signed by the librarian had to be first obtained by visitors. Relaxation of these rules was made by the librarian only in special cases, and a visitor's book was opened which all those admitted had to sign. Later on these rules were somewhat modified, in that admission by ticket was limited to Mondays and Thursday only, and on Saturdays admission was free.

Soon the Library acquired international fame and became celebrated for possessing the most valuable collection of oriental manuscripts in existence whether in Europe or in Asia, and because of its extremely generous policy of loans it was greatly esteemed abroad. Manuscripts were loaned to accredited scholars writing books relative to India as well as to various learned societies and institutions of Europe, to whom also gifts were made of valuable volumes in the Library's possession. Thus a policy of exchange of publications was initiated, an important step in the history of the Library.

This rapid expansion of the Library, however, brought accompanying problems of space and cataloging of materials. Wilkins found these more and more difficult to cope with, especially in view of his advancing years. He continued to hold his post until his death on May 13, 1836, when he was nearing ninety. He had served for thirty-five years as librarian and had received many honors. He was elected a Fellow of the Royal Asiatic Society in 1788, and the Institut de France had already made him an associate. The University of Oxford conferred on him the honorary degree of Doctor of Civil Law on June 26, 1805; in 1825 the Royal Society of Literature awarded him one of their royal medals as "Princeps Literaturae Sanskritae"; and in 1833 the honor of knighthood and the Guelphic order was conferred on him by the King. He continued to attend Haileybury College as visitor examiner twice a year. As the Sanskrit language was an important subject of study there, and a Sanskrit grammar was badly needed, Wilkins published his Sanskrita Grammar in 1808, to have it hailed as "a model of clearness and simplicity and which greatly contributed to the study of the primeval tongue." 19 [Gentleman's Magazine, op. cit., p. 97.] For similar reasons he superintended a new edition of John Richardson's A Vocabulary, Persian, Arabic and English in two volumes and in 1815 also published a list of the roots of the Sanskrit language.

C. Other Nineteenth-Century LibrariansHorace Hayman Wilson was next appointed to succeed Wilkins. He had gone out to India as an assistant surgeon in the service of the East India Company and had later been assistant to the great Scottish orientalist, John Leyden, at the Calcutta Mint. Inspired by Jones, he had taken up the study of Sanskrit and produced the first Sanskrit- English dictionary. At the time of Wilkins' death, he held the Boden Chair of Sanskrit at Oxford, and his dictionary, of which a second edition was published in 1832, had become the standard work of reference for all European scholars of oriental literature. He was an indefatigable worker, and all through his life, apart from working full time with great enthusiasm and interest for the Library, he held late evening classes regularly to fulfil the duties of his professorship. Under his direction, the first catalog of printed books of the Library was published in 1845, and a supplement in 1851.20 [Dictionary of National Biography (London: Oxford University Press, 1921-22), XXI, 568-69.]

Wilson lived to superintend the removal of the Library from Londonhall Street to Cannon Row after the suppression of the Indian Mutiny in 1858, when the powers and the functions of the East India Company were transferred to the Crown. A new department, the India Office, was set up under the newly created "secretary of state for India in council." The Library was temporarily housed in Cannon Row and the much enlarged Museum moved to Fife House, Whitehall. The East India House was put on sale and most of the furniture and fittings auctioned. Wilson died in 1860, before the new India Office in Whitehall became the permanent home of the Library.

He was succeeded in 1861 by James Ballantyne, who had spent several years at the Benares Sanskrit College as principal and professor of moral philosophy. He had to his credit several philosophical works representing eastern thought for the benefit of the Europeans, and vice versa, and translations and monographs on Hindi, Urdu, and Marathi. He died early, however, so that only three years after his appointment, in 1864, the office of librarian was again vacant. Ballantyne was followed by Fitzedward Hall, another Sanskritist of high repute who, however, resigned five years later because of conflict with his colleagues. He is especially noted for his collaboration with Sir James Murray in the preparation of the Oxford Dictionary, to which he devoted most of his time for many years.

His successor was the great scholar Reinhold Rost, who is considered almost as great a linguist as Sir William Jones and was at the time acting as secretary of the Royal Asiatic Society. "There was scarcely a language spoken in the Eastern hemisphere with which he was not to some extent familiar. His mastery of the Sanskrit language was complete and the breadth of his Oriental learning led scholars throughout the world to consult him repeatedly on points of difficulty and doubt." 21 [Ibid., XVII, 291.] His twenty-four years of librarianship were particularly noteworthy for the great progress made in cataloging and arranging the manuscript collections. According to the Dictionary of National Biography, he found the Library "a scattered mass of priceless, but unexamined and unarranged manuscripts and left it to a large extent an organised and catalogued collection, second only to that of the British Museum."

He retired under the Civil Service Rules in 1893 and was succeeded by Charles H. Tawney, who had a distinguished career in the Bengal Educational Service and had edited and translated several Sanskrit works. During Tawney's time further progress was made in the publication of catalogs of manuscript and book collections. Thus, under the guidance and direction of a succession of great scholars, the Library continued to grow and expand and became the most celebrated special oriental library in the world, its growing collections increasingly well arranged and organized.

Meanwhile, the Museum had been heading toward a different end. As we have seen, it had already been separated from the Library when it was moved to Fife House after the breakup of the East India Company in 1858. On the opening of the India Office in 1867, the two institutions were brought together again and the entire top floor of the building was put at their disposal. The Museum, however, was difficult of access, and it was clear that the crowded masses of treasures which filled it to overflowing needed larger and better accomodation. J. Forbes Watson, who was then in charge as Reporter on the Products of India, submitted a plan to the secretary of state in council for a new building to be erected opposite the India Office in King Charles Street, to house both the Library and the Museum.22 [International Congress of Orientalists, Report of the Proceedings of the Second International Congress of Orientalists Held in London, 1874 (London, 1874), pp. 46-52.] He strongly believed that the two institutions should be under the same roof, because almost every object in the Museum needed to be supplemented by the Library, while, on the other hand, the Museum collections served as useful illustrations to the subjects referred to in the books the Library possessed. Though the scheme had the approval of the secretary of state in Council, the home government did not give its co-operation or the necessary financial aid. So the Museum, to everybody's regret, had to be dissolved, and its collections were ultimately distributed between South Kensington, the Bethnal Green Museum, the Royal School of Mines, and the Kew Herbarium. Most of the collection of natural-history drawings, which had grown along with the specimens in the Museum, was retained, however, and remains one of the most valuable possessions of the India Office Library.

D. Twentieth-Century LibrariansOn the retirement of Tawney in 1903, F. W. Thomas, assistant librarian since 1898 and one of the greatest of Indologists, took charge and held the office of librarian until 1927. He was a man of profound learning and varied scholarly interests, in addition to possessing an inexhaustible fund of energy. His long period of office as librarian was one of great activity in which many far-sighted plans and projects were initiated. The Library made rapid progress in many directions. There was an enormous increase in its collections, and a great many catalogs of manuscripts and printed books were prepared and published. In a memorial note for the 1956-57 annual report, S. C. Sutton, the present librarian, wrote of Thomas, "The elaborate plans which he laid down early in the century for classifying and describing the Library's uncatalogued resources have continued to yield results to this day."

What Thomas was able to accomplish in his time to bring the Library abreast of the moment was truly an immense achievement, especially as it was faced with difficulties of all sorts. Lack of funds was a constant problem; to obtain special grants for various projects such as repairing and binding manuscripts was a hard and continuous struggle; and, when sanctioned, funds always fell short of requirements, as binding charges rose continually due to war conditions. For the same reasons, such high prices were quoted by printers at times that the publication of completed catalogs often had to be postponed. The compilation, revision, and completion of catalogs presented difficulties on account of the variety and alphabetic peculiarities of the languages to be dealt with; and the work often had to await the discovery of a suitable language expert. Often work suffered also because of lack of wall space. Nor did the general shortage of staff help matters. In 1917 it consisted only of the librarian, an assistant librarian, four clerks, two attendants, and two laborers.23 ["Annual Report of the India Office Library, 1916-1917" (in the files of the India Office Library, London; until the year 1949-50 the reports are unpublished, but from 1950-51 they are published regularly every year in London).]

During these war years many transfers and temporary appointments added to the difficulties of getting work accomplished in time. These uncertain and fluid arrangements continued for some time after the war until, on the librarian's insistence, a complete reorganization of the staff was effected in 1919, the staff being, with the exception of the librarian himself and the assistant librarian, wholly reconstituted.24 ["Annual Report . . ., 1928-1929."] An expert in library work was appointed to fill a new post of sublibrarian. A few years later, in 1925, all the Arabic and Persian manuscripts were placed in sole charge of a distinguished scholar of Islamic literature, Sir Thomas Arnold. By then oriental studies had reached such a stage of complexity that it had become impossible for one person to possess sufficient knowledge of all the three classical languages and literatures required to administer the resources of the Library with any degree of efficiency. In 1926, the librarian's proposal for the compilation of a catalog of oriental drawings in three sections: (a) Mohammedan, (b) Hindu, and (c) Other, was approved,25["Annual Report . . ., 1935-1936."] and naturally Arnold was intrusted with the section devoted to Mohammedan drawings, which exceeded all others in number.

Thus, in spite of the war years and their attendant difficulties, work proceeded with reasonable rapidity, and new policies for better organization were considered and adopted. As already mentioned, there was a tremendous growth in the Library's collections during this period, and many valuable manuscripts, both European and oriental, were received by presentation or purchase. Most significant were large numbers of documents and manuscript fragments in Sanskrit, Kuchean, Khotanese, and Tibetan recovered by Sir Aurel Stein through systematic exploration in Chinese Turkestan. The Sanskrit and Tibetan manuscripts from these collections attracted Thomas' scholarly attention, and he set himself the arduous task of examining these rare manuscripts with great eagerness and interest. "As a librarian he imposed admirable order upon this great collection and as a scholar, he devoted years of patient research to the interpretation of these unique and very ancient documents." 26 [New Indian Antiquary, Extra Series I: A Volume of Eastern and Indian Studies in Honour of F. W. Thomas (Bombay: Karnatak, 1939), p. x.] His numerous writings on these manuscripts were published in the Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society in instalments from time to time. Those of Tibetan interest were later published in Volumes I, II, and III of his Tibetan Literary Texts and Documents Concerning Chinese Turkestan (London, 1935, 1951, and 1955). He continued this research work during the years following his retirement from the Library and gave invaluable assistance in the preparation of the complete catalog of Stein Tibetan material which the Library published in 1962.27 [Interview with S. C. Sutton, librarian, India Office Library, and keeper of records, India Office Records, August 15, 1964.]

There was also a substantial increase in the book and periodical collections. They were, as before, for the most part requisitioned under the Indian copyright law by marking the Indian Quarterly Catalogues issued by various Indian administrations; some were received from the Records and Registry Department of the India Office, these consisting mainly of official publications, many being periodical and recurrent -- acts, proceedings, civil lists, and calendars. Many were purchased, however, and there were numerous presentations. What was ultimately retained in the Library depended often on the advice of scholars engaged in cataloging.

Thomas retired in 1927 at the age of sixty to fill the Boden Chair of Sanskrit in the University of Oxford. He was succeeded by C. A. Storey, a distinguished scholar of Arabic and Persian. Assistant librarian since 1919, he had devoted much time and labor to the cataloging of the important Delhi Collection of Arabic and Persian manuscripts, the organization of which made its first real progress under him. As librarian, he took a keen interest in every detail of the Library's activities and functions, and his scholarly interests and methods made a distinctive contribution to its growth and development. There was a notable increase in the number of readers during his period of administration, going up to 4,756 in 1928-29 as compared with 2,586 in 1926-27,28 ["Annual Report . . . 1928-1929."] Originally initiated by Thomas, the plan for the publication of a series of catalogs of the European manuscripts was carried forward with rapid success, and several volumes were printed. Before he retired in 1933 to take up the Sir Thomas Adams' Professorship of Arabic in the University of Cambridge, he had published the first part of the descriptions of the Arabic manuscripts from the Delhi Collection and was still working on those of the Persian manuscripts and on the revision of his detailed catalog of the whole collection of Arabic printed books.

H. N. Randle, a learned and well-known scholar of Sanskrit, who had been on the staff of the India Office Library as assistant librarian since 1927, succeeded Storey as librarian in 1933. Two other important appointments were made soon afterward, that of A. J. Arberry in 1934 as assistant librarian and assistant keeper of oriental printed books and manuscripts, and of Sutton as sublibrarian in 1935.29 ["Annual Report . . ., 1935-1936."] Arberry, a remarkable scholar of Arabic and Persian, made a most valuable contribution in compiling the Library's Catalogue of Persian Books (1937) and the second fascicule of Volume II of the Catalogue of Arabic Manuscripts. In addition, he was constantly engaged in writing and publishing scholarly works on Arabic and Persian literature. Sutton, a graduate of the London School of Economics and Political Science, had professional library qualifications. Under his able guidance and supervision it became possible to reorganize many of the Library's techniques and to remove defects of the existing system, thus bringing it abreast of modern librarianship. His views on these matters were particularly valuable when the secretary of state appointed a Committee of Investigation into the Library and Record Department "to consider, with a view especially to facilitating the access of enquirers to sources of information, whether any changes could usefully be made in the present arrangements in the Library and, also, in particular, in the relations between the Library and Record Department.'" 30 [Ibid.] Sutton acted as the secretary of this committee and participated in all its deliberations. The committee, reporting in 1936, made the following principal recommendations:31 [Ibid.; see also Great Britain, India Office Library, "Report of the Committee of Investigation," No L. 390/36 (in the files of the India Office Library, London).]

1. That card catalogues of all the collections of oriental printed books be made accessible in the Reading Room and a subject catalogue published.

2. That the European printed books be recatalogued in order that an author catalogue on typed cards may be assembled in the Reading Room and a subject catalogue published.

3. That two permanent graduate assistants with professional library qualifications be appointed, one to be occupied for the first four years in recataloguing European books, and that a temporary assistant with similar qualifications be appointed for four years to assist in this recataloguing.

4. That an orientalist be appointed in charge of the section of modern Indian languages.

5. That the Library be provided with additional rooms, both for shelving and for staff, contiguous to its present quarters.

The secretary of state's acceptance of those recommendations in 1936 was a great step forward in the history of the Library. Many changes took place in its organization during the year 1936-37. Three appointments to the newly created grade of assistant were made, all the appointees holding a diploma in librarianship. One of them, Miss Bowker, was placed in charge of the European periodicals, manuscripts, and photograph collections, besides being intrusted with the task of compiling indexes to Part II of the second volume of the Catalogue of European M3anuscripts. The other two assistants, Miss A. F. Thompson and Miss Pexton, were given the responsibility of recataloging the European printed books. Five more typists were also engaged especially to assist in this new cataloging scheme.32 ["Annual Report . .. ,1936-1937."]

The scheme was devised by Sutton with a view to making the cataloging system of the Library consistent with modern practice. It was decided: (a) to introduce subject cataloging by compiling and eventually publishing a complete alphabetical subject catalog with author index; (b) to supplement this printed catalog by a subject catalog on cards which would be printed at regular intervals and cumulated at longer intervals; (c) to use the library of Congress subject headings with certain modifications to meet the Library's special needs; (d) to replace the existing expansible author catalog-the Green Catalogue-of pasted-in entries in eight folio volumes which, due to increasing congestion of entries, was on the verge of a complete physical breakdown, by an indefinitely expansible author catalog on typed cards placed in the Reading Room; and (e) to adopt the rules of the Anglo-American Cataloguing Code.33 ["Annual Report . . . , 1935-1936"; see also Great Britain, India Office Library, "Library Records," No. L 204/35 (in the files of the Library).]

Other features of the scheme were to maintain accession registers, which would thus form a permanent record of the Library's acquisitions, and to shelve works by accession numbers and by size instead of by subject, in order to save shelf space.

To implement the scheme, the work of recataloging was begun in earnest by the newly appointed assistants, who were also charged with the task of compiling a shelf list, a list of incomplete works, and a periodicals list.

The cataloging of oriental works and publication of the much-needed catalogs proceeded as rapidly as possible. The publication of the Catalogue of Sanskrit Manuscripts, compiled by outside scholars, of which the first seven volumes were published between 1889 and 1904, was completed in the year 1935. Material for the printing of catalogs of Sanskrit books was prepared by Randle himself, and the first volume was published in 1938. Current Sanskrit accessions were cataloged on cards, also under his supervision, and filed in the Reading Room. As for the cataloging of the Islamic collections, it was decided that it should be the duty of the assistant keeper in charge of them. Arberry therefore took over complete responsibility and was provided with the special services of a clerical assistant, so that cataloging in this section proceeded very rapidly. But the preparation of catalogs of manuscripts and books in modern Indian languages presented unusual difficulties because it was not easy to find scholars competent enough to deal with them, especially those in the Dravidian languages; but advantage was taken from time to time of the presence of Indian scholars in England who were willing to render their services to the Library. The Catalogue of Malayalam Manuscripts in the India Office Library (London: Oxford University Press, 1954) was thus prepared and completed by C. A. Menon of Madras University during his sojourn in England, and in the course of this work it was discovered that the two Malayalam documents, one on gold, one on silver, which had been lying in the Library safe for years, were seventeenth- century agreements between the Zaimonn of Calicut and the Dutch East India Company.34 ["Annual Report . . ., 1936-1937."]

As for printed books, some catalogs covering several languages, mainly North Indian, had been compiled by J. F. Blumhardt and published several years earlier. They needed to be brought up to date, however, especially as the intake of books in this section had been very large and heterogeneous. Various efforts had been made to find suitable successors who could produce printable supplements, but without success. Typed staff cards of current accessions were made and filed by Gonsalves, the "oriental clerk" who had been employed since 1919 35 ["Annual Report .. . , 1939-1940."] to supervise modern- language accessions, but these were not suitable to be used for the public card catalog. The voluminous intake of books also inevitably caused accumulation of arrears. The Committee of Investigation, therefore, had recommended the employment of additional clerks to help Gonsalves complete listing uncataloged arrears and start converting the staff cards into author and title cards which could be housed in the Reading Room accessible to the readers. The work made good progress, though the gap between the printed catalogues and the accessible typed cards remained; and since these new cards were not suitable for printing, satisfactory arrangements for printed catalogs were still necessary. Consequently, the appointment of an orientalist responsible for the care of the modern language section seemed the only solution. The committee had recommended such an appointment, and this was at last made in 1938, when R. H. B. Williams, a specialist in Dravidian tongues, became assistant keeper of printed works in modern Indian languages.

In further fulfilment of the committee's recommendations, the Library's premises were extended, a whole block of additional rooms on the third and fourth floors being provided for the use of the staff and stacks. New card-catalog cabinets for the Reading Room's Author Catalogues were purchased, and the lighting arrangements in the Reading Room were also improved. Sutton was appointed to the newly created grade of assistant keeper, the post of sub-librarian being abolished. The title of "librarian and keeper of oriental printed books and manuscripts" was also converted to the simple title "librarian," and that of "assistant librarian and keeper of oriental printed books and manuscripts" to "assistant librarian."

In November 1937, the Library became an "outlier library" of the National Central Library. As a result, it became possible for its readers and staff members to borrow works not in the Library, with the exception of recent fiction, while its own works became available, through the National Central Library, to readers registered in other libraries of the United Kingdom.