Part 4 of 4

2. OrientalThe oriental manuscripts in the possession of the Library are about 20,000 in number, some of the largest collections being in Sanskrit (8,300 manuscripts), Persian (4,800), Arabic (3,200), and Tibetan (1,900). In addition, there are numerous fragmentary manuscripts in Sanskrit, Tibetan, Khotanese, and Kuchean. Modern-language collections are much smaller, however, and in general of less interest. Apart from those in Hindi (160 manuscripts), Marathi (250), Gujarati (140), Bengali (30), Oriya (50), Urdu (270), and Pashto (60), there are several from adjacent countries as well, such as the Burmese (250 manuscripts), the Indonesian (110), the Sinhalese (70), the Mo-so ( 111), and the Turki and Turkish (23).95 [The India Office Library, pp. 4-5.]

a) Sanskrit manuscripts.-- Of the Sanskrit manuscript collection, the most important contribution was that of Henry Thomas Colebrooke, consisting of 2,749 manuscripts which he presented to the Library in 1819. This vast collection, the most munificent gift the Library has ever received, covering all branches of Sanskrit literature and science, was formed by Colebrooke during his thirty-two years in India, where he lived a life devoted to the pursuit of severe and abstract studies, in addition to the performance of his official duties, which engaged his interest and attention no less. His father was a member and three times chairman of the Court of Directors of the East India Company. It was natural, therefore, that he should be appointed to a writership in the Bengal Civil Service. He went out to Calcutta in 1782 at the age of seventeen, by which time, having been a voracious reader from his early days, he had already acquired a considerable mastery of Latin and Greek along with French and German and had also developed a passionate interest in mathematics.

A short time after his arrival he took up the study of Sanskrit mainly because of his desire to acquire knowledge of the ancient algebra and astronomy of the Hindus. One other factor that helped to stimulate his curiosity in Hindu antiquity was the foundation of the Asiatic Society and the series of learned essays by the great oriental scholar, Sir William Jones, which began to appear in profusion in the society's journal, Asiatic Researches; and later, when he began to exercise judicial functions, the difficulties of administering justice among the people according to their own laws also made it essential for him to learn Sanskrit and to read the Hindu law books in the original. By 1793 he had become deeply absorbed in the study of Sanskrit literature and was writing to his father in such words as these:

Hindu is the most ancient nation of which we have valuable remains and has been surpassed by none in refinement and civilisation.... The further our literary enquiries are extended here, the more vast and stupendous is the scene which opens to us; at the same time that the true and false, the sublime and the puerile, wisdom and absurdity, are so inter-mixed that at every step we have to smile at folly, while we admire and acknowledge the philosophical truth, though couched in obscure allegory or puerile fable.... I have only to wish for more leisure for diligent study in their literature.96 [H. T. Colebrooke, Miscellaneous Essays, with the Life of the Author by His Son, Sir T. E. Colebrooke (London: Triubner, 1873), I, 61.]

With incessant and intense application he acquired such profound and critical knowledge of the Sanskrit language that in 1795 he was able to undertake the important work of translating from the original the digest of Indian law compiled under the direction of Sir William Jones before his death in 1794. Colebrooke labored on this translation with unremitting exertion during the only free time his official duties left him in the evenings, without remuneration and paying the pundits out of his own pocket. The digest appeared in 1798 and established his reputation as a great scholar. The value and thoroughness of the work and the services he had thus rendered won him the appreciation of all members of the government, and this led to his being appointed a member of the Supreme Court of Appeal, established in Calcutta in 1801. Four years later he became its head and in 1807 attained a seat on the Supreme Council of Bengal, the highest honor accorded to a civilian. His contributions to legal science as a member of the Supreme Court were considered, at the time, as important as his work and achievements in the field of Indian literature.

Simultaneous with his appointment to a seat on the bench in 1801 he was appointed to the professorship of Hindu law and Sanskrit at the College of Fort William, established that year in Calcutta -to provide instruction for the young members of the Civil Service. Here he acted as an examiner for some time in the Sanskrit, Prakrit, Bengali, Hindi, and Persian languages. At about this period he also wrote and published a brilliant essay on the Sanskrit and Prakrit languages which proved his complete mastery of the subject. In 1805 appeared the first volume of his Sanskrit grammar in which he had made an attempt to arrange methodically the intricate rules of Panini's Grammar and his commentators. Colebrooke was the first to realize the importance of Panini's Grammar and to make these works intelligible to succeeding scholars. Studies in comparative philology and deciphering of inscriptions engaged his attention next. Thus he lost no opportunity of pursuing a varied and extensive course of study in oriental science and literature and contributed many papers on these subjects to the Asiatic Researches.

One of the most important contributions to research in the field of oriental literature was his essay on the Vedas, which has been recognized as the first authentic account in English of these ancient sacred writings. In this essay on the Vedas he has taken infinite pains to prove at great length the authenticity of the manuscripts he had managed to secure. The precise logic of his arguments in support of his opinion left no doubt in the minds of scholars that the collection of works he had in hand were the genuine ancient scriptures of the Hindus. "His own manuscripts remain in evidence that the task he set himself was performed with a closeness and severity of study that has been rarely equalled. The Vedic manuscripts he presented to the Library of the East India Company indicate by marginal notes, sometimes by translation of the hymns, that before presenting to the world his review, he had made himself master of the contents of those obscure and voluminous records."97 [Ibid., p. 242.]

Colebrooke formed his unrivaled collection of manuscripts over a period of many years, and it is thought to have cost him about £10,000. 98 [J. J. Higginbotham (ed.), Men Whom India Has Known (Madras: Higginbotham, 1874), p. 79.] They were bought by him whenever and wherever an opportunity presented itself. He never missed a chance to add to his treasures or of discoursing with learned Brahmins on the contents of the manuscripts he succeeded in obtaining from them. Among the most valuable manuscripts he gathered thus were commentaries, including one by Sayana, the most important of scholiasts, on two of the Vedas, giving detailed renderings of the originals in classical Sanskrit. The earlier Vedas were written in a style so obsolete that, had it not been for the discovery of these commentaries by Colebrooke, the contents of the Vedas would not have been known to the western world for a very long time. That he took the greatest care in selecting absolutely correct versions of manuscripts is evident from the following extract of a letter he wrote to A. W. von Schlegel, with whom he corresponded from time to time:

The carelessness of the native editors and publishers of works in India, joined with the ravages of worms and termites is very discouraging to the importation of books thence. Your animadversions are well merited. I could never impress on the native correctors of the press, while I was there, the duty and necessity of careful revision. They are slovenly with the press, as with manuscripts, which are commonly very incorrect. It was, on that account, my habit to purchase old manuscripts, which had been much read and studied, in preference to ornamented and splendid transcripts imperfectly corrected. I feel it difficult to answer your inquiry concerning the price of manuscripts in India. When I was myself residing in the vicinity of Benares, I was enabled to purchase books at moderate prices. At all other places I found them very dear, and the expense of transcripts properly made was enormous. I should be at a loss to recommend to you an agent who would take sufficient care, and would rather advise your purchasing in England, where Oriental manuscripts are sometimes for sale, falling into the hands of Orientalists.99 [Colebrooke, op. cit., p. 329.]

Colebrooke presented the whole of this great collection of Sanskrit manuscripts to the Library of the East India Company in 1819, a short time after his return to England, a step taken solely because he thought the collection to be too valuable to keep entirely to himself, especially as interest in oriental literature was growing rapidly among Continental as well as English scholars, for whom, he felt, easy access to these priceless manuscripts would be of immense benefit. "In making over to a great corporation like the East India Company, he had a guarantee that the interests of literature and science would be fully considered." 100 [Ibid., p. 328.]

The offer of this most generous gift was made in a brief letter and was, naturally, accepted with gratitude:

"LONDON, APRIL, 1819.

"SIR,

"Intending to present to the Honourable East India Company, to be deposited in their library and museum, my collection of Oriental Manuscripts, consisting chiefly of Sanskrit and Pracrit works, I have the honour through you to make the offer of it to the Honourable Court of Directors, on the sole condition that I may have free access of it, with leave to have any number of books from it for my own use at home, to be sent to me from time to time, on my requisition in writing to the Librarian to that effect, that to be returned by me at my convenience.

"To facilitate access it may be necessary that the books should be arranged and a catalogue of them prepared, but on this point I do not think it requisite to make any stipulation, or offer any particular suggestion.

"I have the honour to be, etc.,

H. COLEBROOKE.

"Dr. Wilkins."101 [Ibid.]

The following list of volumes of manuscripts, many of them comprising more than one work or treatise each, supplied by Colebrooke to the then librarian, gives us a general idea of the character of the collection:

Mantra (prayers, etc.) ...... 56

Vaidya (medicine) .......... 57

Jyotisha (astronomy) ....... 67

Vyakarana (grammar) ....... 135

Vedanta ................ 149

Nyaya ................ 100

Veda ................ 211

Purana ................ 239

Dharamsastra (law) ........ 215

Kavya, nataka, alankara ..... 200

Kosha (dictionaries) ........ 61

Manuscripts of all kinds ..... 52 bundles 102 [Ibid., p. 327.]

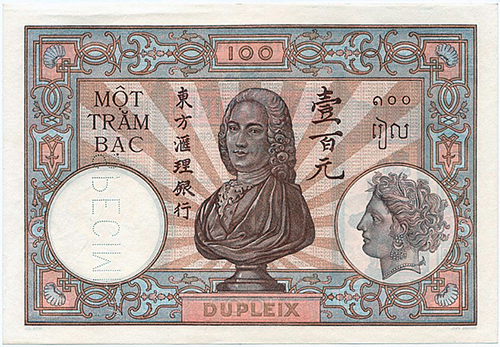

There is no doubt that Sanskrit studies in the West were profoundly and lastingly stimulated by Colebrooke's presentation of his rich accumulation of manuscripts to the Company's Library, where they became freely accessible to other orientalists of his own day and of the future. A Chantrey bust of this great scholar and Library benefactor, commissioned by the Court of Directors of the East India Company in 1820, adorns the main corridor of the India Office Library.

The Buhler Collection, consisting of 321 manuscripts, was presented to the Library in 1888 by Johann Georg Buhler. It was formed by him between the years 1863 and 1888, when he was in India as professor of oriental languages at the Elphinstone College in Bombay or holding posts in the educational service. Deeply interested in Sanskrit philology and Indian history, he was most anxious to acquire as many unpublished works as possible which, he thought, might help him solve some of the complex problems these subjects presented at the time. Immediately after his arrival in Bombay, he began his search for manuscripts in earnest, and the difficulties he encountered at first were numerous. To overcome the orthodox sentiments of the Brahmins, who possessed manuscripts of rare value, was not easy, for they considered "the traffic with the face of Sarasvati [Hindu goddess of learning] to be impious and hated the very thought of giving their sacred lore to the Mlechchhas [barbarians or untouchables]."103 [Georg Buhler, "Two Lists of Sanskrit Manuscripts . . . ," Zeitschrift der Deutscher Morgenlandischer Gesellschaft, XLII (1882), 530-36.] However, there were some who were not averse to indulging in the trade in secret, and soon Buhler was able to purchase a large batch of fragments and modern copies of manuscripts, and paid exorbitant prices for them. A little later he obtained permission to have copies made of an important government collection of manuscripts in Madras, for which purpose he had to employ a Brahmin who could transcribe from the Dravidian characters into Devanagari. This person, the only one in Madras so qualified, worked for Buhler for four years (1863-67).

In 1864, as a member of the committee appointed by the Bombay government to edit a digest of Hindu law cases, Buhler found he would have to make a serious study of the Dharmashastra in the original and, therefore, needed many unpublished works. He then publicly announced that he was willing to pay any price for the manuscripts he wanted, with the result that several people from different parts of India came forward to render their services and Buhler was thus able to secure quite a few valuable manuscripts. In Poona too, where he was a professor temporarily at Deccan College, he succeeded in having copies made of some very rare and fine old manuscripts which the college shastris lent him for the purpose. And, sometimes, while he was there, unknown Brahmins, in financial distress, went to sell manuscripts to him in secret, being afraid of open dealings with him, a mlechchha.

By the end of 1866 he had thus collected between three and four hundred old and new manuscripts-consisting mainly of Vedic literature, kavya (poetry), alamkara, and dharma-and some scattered works on practically all other Shashtras, thus expending all his savings on these purchases.104 [Ibid., pp. 536-59.]

From November, 1866, onward he collected manuscripts mainly on behalf of the government of India from various parts of India; and, when he found that there were more manuscripts for sale than the government funds at his disposal could buy, he offered to collect, against payment, for European libraries, especially as he knew that unsaleable manuscripts only went into the hands of paper manufacturers in India, were reduced to pulp, and thus lost forever. Now and again, on these tours, he was able to make additions to his private collection as well. It was this collection, considered to be one of the most valuable Sanskrit collections of the Library, which he took back with him to England in 1888 and presented to the India Office Library, with the exception of some one hundred manuscripts which he had presented at various times between 1868 and 1878 to the Royal Library in Berlin and a few birch-bark specimens that he presented to the Royal Asiatic Society in London.

Other noteworthy Sanskrit manuscript collections in the Library may be mentioned, first, the 1,165 manuscripts from the Mackenzie Collections purchased between 1822 and 1833. Many of them, according to H. H. Wilson, are rather difficult to decipher, being inscribed, uninked, on palm leaves, and better copies of them exist elsewhere.105 [Wilson, op. cit., p. 534.] There are, however, some of local origin and interest giving legendary histories of celebrated temples and places of pilgrimage scattered through South India. From these, as well as from a few historical and biographical narratives, it is possible to glean some knowledge of real events. The most important part of these manuscripts is the literature of the Jains. Mackenzie is credited with being the first to notice and describe the particular tenets of this sect, then dispersed throughout India, especially in West and South India. He derived most of his information by personally interviewing members of their community and by visiting their principal shrines and temples. His paper relating to the Jains, along with those of Buchanan and Colebrooke, which were published in Volume IX of the Asiatic Researches, offered to Europeans for the first time an authentic account of this sect. The second noteworthy collection, the Aufrecht Collection, was acquired in 1904 from Theodor Aufecht, German Sanskrit scholar and philologist who was famous for his great work of reference, Catalogus Catalogorum (3 vols., 1891-1903), and is a register of all known Sanskrit works and authors from 1893. The Aufrecht Collection consists of (1) a large number of carefully annotated manuscripts (mainly Vedic and Brahmanical literature) copied mostly by Aufrecht himself from originals in Europe or India, some copied by others, and a few originals; (2) glossaries or word indexes; and (3) pratika indexes, that is, arrangements of initial words of verses, mantras or sutras, all compiled by him in the course of his Sanskrit studies and research.106 [See the handlist of the collection compiled by F. W. Thomas, "The Aufrecht Collection," Journal of Royal Asiatic Society (1908), pp. 1029-63.] The third collection is the Tagore Collection, containing 140 manuscripts donated by Rajah Sourindra Mohan Tagore in 1902. Fourth is the Burnell Collection, half of which was presented to the Library by A. C. Burnell, another eminent Sanskrit scholar, in 1870, and the rest purchased later in 1882. Fifth are 507 manuscripts presented by the Gaekwar of Baroda in 1809. There are also numerous Sanskrit manuscripts from the collections of oriental manuscripts formed by Sir Charles Wilkins, H. H. Hodgson, and others.

b) Persian and Arabic manuscripts.-- The Library's collection of Persian and Arabic manuscripts has been formed from several special collections acquired at various times in the Library's history, some of the major ones being the Tippoo Sultan Collection, the Delhi Collection, the Bijapur Collection, and the Royal Society Collection. Other notable collections from which the Persian and Arabic manuscripts have been derived were those formed by Warren Hastings, Richard Johnson, John Leyden, the great orientalist Sir Williams Jones, and others, all of whom spent years in India in the service of the East India Company and who either sold or presented their collections to the Company's Library in London on their return to England.

Many of these manuscripts are very rare. Some are illuminated and contain numerous splendid illustrations; others have rare examples of calligraphy. One of the most important manuscripts in these Islamic collections, being the only one in existence, is the Farman of Babar, a Persian manuscript with the seal of Babar and dated A.D. 1526 (933 A. H.). In the Delhi Collection is another very rare Persian manuscript, "Ibtida-Namah," by Sultan Walad, the son of the famous Persian poet Jalalud-din Rumi, containing Dara Shukoh's inscriptions. There is also the unique illuminated Arabic manuscript, "Al-Durar-al-Mathurat," a work on the text of the Koran. A great many illuminated manuscripts come from the Johnson Collection, including a fine "Laila-Majnun" of the sixteenth century Persian poet Nizami and a collection of seven Persian diwans of the Mongol period in Iran dated about A.D. 1314. This collection of diwans is the earliest illustrated manuscript in the Arabic and Persian collections. It belonged to Shah-Ismail Safavi of Iran and contains several illustrations of the Persian poet presenting his works to the Mongol sultan. A magnificent "Shahnamah," copiously illustrated with the text illuminated in gold, is derived from the Hastings Collection, and the unique illustrated Persian manuscript "Sindbad-namah" comes probably from the Tippoo Sultan Collection.107 [Based on interviews with Miss J. R. Watson, assistant keeper, Islamic Collections, India Office Library, and examination of the manuscripts, July 10 and 17, 1964.]

The Tippoo Sultan Collection was formed from the Library of Tippoo Sultan of Mysore which fell into the hands of the Company's army after Tippo's final defeat at Seringapatam in 1799. As found then, it consisted of about 2,000 volumes of mainly Arabic and Persian manuscripts, covering various branches of Asiatic literature, and a great many very important original state documents. The greater portion of the manuscripts was acquired by Tippoo and his father, Hyder Ali, through conquest and usurpation, very few of them having been actually purchased by either of them. They were part of the spoils gathered after inflicting defeats and pillaging forts of various Mohammedan kings of the surrounding states: Carnatic, Sanoor, and Kuddapah.108 [ Charles Stewart, A Descriptive Catalogue of the Oriental Library of the Late Tippo Sultan of Mysore (Cambridge, 1809), pp. v-vi.] One of the choicest collections, consisting of beautifully written and illuminated manuscripts, which found its way into Tippoo's library was the one assembled at great expense by Anwar Addeed Khan of Carnatic, who fell at the hands of Hyder Ali in 1780. 109 [Ibid., p. 32.]

A great many of these manuscripts were rebound at Seringapatam by Tippoo with very distinctive leather bindings. Some of them bore the private seal "Tipu Sultan." Famous among these are a Koran and a gorgeous "Shah-namah." Most of the manuscripts deal with theology and Sufism, subjects that interested Tippoo most; others were on history and biography. In addition, there were at least "forty-five books on different subjects composed or translated from other languages under his immediate patronage or inspection, and in all of these his intolerance and aversion to- all Christians and Hindus were clearly marked." 110 [Ibid., pp. v-vi.]

The numerous documents and original state papers found in Tippoo's library proved to be of great historical interest. They included several papers relating to Tippoo's government, the constitution of his military force, the resources of his dominions, and, more important, voluminous records of his intrigues and negotiations with the French and other designs to drive the British from India. In fact, in all these papers there was ample material for a complete history of the reigns of both Hyder Ali and Tippoo and Tippoo's determined fight against the British right until his fall in 1799. 111 [A. Beatson, A View of the Origin and Conduct of War with Tippoo Sultan (London: G. & W. Nicol, 1800), p. 179.] Apart from such material of great value, also found in his library were several memoranda, collections of orders, etc., and other miscellaneous papers in the Sultan's own handwriting, including a register of his dreams,112 [See above, p. 102.] a memoir written by himself, and many of his letters, all of which shed a great deal of light on his character and genius. Many of these papers were examined by Colonel William Kirkpatrick of the East India Company, who made a full report on them to the governor-general on July 27, 1799. 113 [Beatson, op. cit., p. 179.] He also translated some of Tippoo's letters in a volume published in London in 1811 under the title Select Letters of Tippo Sultan. A copy of this and all Tippoo's original letters are to be found in the India Office Library. As mentioned earlier, a catalog of the whole library of Tippoo Sultan was prepared by Charles Stewart at the order of the directors of the East India Company and published in 1809 at Cambridge with the title A Descriptive Catalogue of the Oriental Library of the Late Tippoo Sultan of Mysore. His evaluation of it and account of how eventually a part of it known as the Tippoo Sultan Collection found its way into the India Office Library has been described previously.

The Delhi Collection, consisting of over 3,000 ancient and valuable manuscripts in Arabic (1,950), Persian (1,550), and Urdu (100), is derived from the original Royal Library of the Mughal emperors. These manuscripts came into the possession of the British armed forces after the reoccupation of Delhi subsequent to the mutiny of 1857. Forty-one cases of these volumes were purchased by the British government in 1859 at the sale of the Delhi-prize property and transported to Calcutta, where they were, for a time, placed in the office of the secretary to the Board of Examiners and then removed to the Calcutta madrissah ("college") for greater security. Here they were carefully examined, classified, and cataloged by Captain W. Nassau Lee, a distinguished scholar and professor, Persian translator to the government and examiner in Arabic and Persian. He made a final selection of the manuscripts worth retaining, the remainder being disposed of by public auction. It was intended to deposit this collection in the new India Museum, then under construction, to form the nucleus of an oriental library, but on the completion of the building in 1876, the trustees of the museum found themselves unable to take charge of it, especially as there were no officers on the staff who had any knowledge of Arabic and Persian; they also considered this proposed branch of the museum to be "alien to the general purposes for which the Museum was instituted." 114 [Great Britain, India Office Records, India Public Consultations, CMLXXXVIII (1876), 815- 16.]

Under the circumstances, the government of India decided to send the manuscripts to the secretary of state for India, suggesting that they be deposited in the Library of the India Office. The manuscripts were carefully packed in tin-lined cases and finally dispatched to London with a number of catalogs toward the end of 1876.

According to all reports, the condition in which these manuscripts were originally received in 1859 was deplorable; several of them had been severely damaged by white ants, and many were "fragments, some without beginning, some without ending and, as is usually the case with manuscripts, several not legible." 115 [India Public Consultations, Range 188, Vol. LIX (1859).] Years of work of repairing and binding had to be devoted to preserving and saving them from complete destruction. The collection, naturally, does not approach the splendors of the original Royal Library, which, as known from the accounts of various travelers, was truly magnificent. In Emperor Akbar's time it would seem that the library consisted of "24,000 volumes valued at Thirty-two lacs, Thirty-one thousand eight hundred and Sixty five Crowns," 116 [Johann Albrecht von Madelslo, The Voyages and Travels of the Ambassadors (London, 1662), p. 48.] but with the gradual decline of the Moghuls, these manuscripts were widely dispersed and many came into the possession of casual travelers and visitors from other countries, who disposed of them later at auctions, as is evident from some of the catalogs and advertisements of Leigh and Sotheby of that period. One reads as follows: "Catalogue and detailed account of the very valuable and curious collection of manuscripts, collected in Hindostan . . . collected at great Expence by the late Dr. Samuel Guise . . . which will be sold by auction, by Leigh and Sotheby . . . on Friday, July 3, 1812 and Four following days (Sunday excepted) at 12 o'clock."117 [India Public Consultations, Range 434, Vol. III (1867), 468-69.]

It is thus only a comparatively small remnant of this great library which has found its way into the India Office Library. Although it does not represent the best part of the original Moghul library, it contains a good many items of rarity and great interest and forms, therefore, an important section of the Persian and Arabic manuscript collections.

The Bijapur Collection, consisting mainly of Arabic manuscripts, was originally part of the library of the Adil-Shahs, kings of Bijapur, whose seals many of them bear.118 [Great Britain, India Office Records, Selections from the Records of the Bombay Government, N.S., No. 41 (Bombay, 1957), pp. 213-42.] At some later stage these manuscripts were removed to Assur Mahal, a sort of religious establishment comprising a college and theological school, founded and financed by King Mohammed Adil Shah for the preservation of a relic of the Prophet. In 1848, when the territory succumbed to the power of the British government in India and was annexed to its dominions, this establishment was found to be existing in name only, with no funds for its support, and the library, housed in a room adjoining the relic room, was in a miserable condition; rats, moths, and white ants had had free access to it for years, and there were perhaps more destroyed volumes than perfect ones. They had been discovered in this condition by the French scholar of Spanish descent, C. D'Ochoa, who visited the country between 1841 and 1843, having been sent by the French government to travel all over the world to collect works of literary and scientific interest. With the special permission of the raja of the state, he examined these manuscripts and "arranged them so far as to separate the more perfect manuscripts from those which were utterly destroyed"119 [Ibid., p. 216.] and prepared a sort of nominal catalog of most of the volumes.

Such was the report that H. B. E. Frere, the newly appointed commissioner of that area, made to the Bombay government, which was interested in having the manuscripts made accessible to the public, and especially to the members of the Bombay branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. As Frere considered the manuscripts to be of great value and worthy of serious study, he had a catalog of them prepared in Urdu by an Arabic scholar brought especially from Hyderabad. This was then translated into English by Erskine, deputy-secretary to the Bombay government in the Persian Department, and on Frere's recommendation that the manuscripts be removed to the Library of the East India Company in London, a copy of the translated catalog was sent to a certain John Wilson for his opinion on the value and interest of the works for European scholars. Wilson, assisted by some local scholars, examined the catalog carefully and made the following report to the governor- in-council:

The Collection viewed as a whole is one of considerable value. Its special interest, however, lies in its containing the body of works which formed the fountain of authority in religion and law to the Beejapoor Dynasty, probably from its formation in A.D. 1489 to its expiration in A.D. 1672. In grammar and lexicography it contains few articles of value; in logic, it is copious; in arithmetic, mathematics, and astronomy or rather astrology, it does not offer much of interest. Of works of poetry, geography and history, in which most interest is felt by European students of Arabic, it is nearly destitute. 120 [Ibid., p. 239.]

Though he considered some manuscripts to be more valuable than others, he did not advise breaking up the collection but recommended that the whole of it be sent as it was to the Court of Directors in London. It was therefore dispatched to London by the governor-in-council in 1853 and deposited in the Library of the East India Company. Here the manuscripts were gradually sorted out, rearranged, repaired, and bound, and a complete catalog was prepared in English by Otto Loth, the librarian, in 1877. 121 [Otto Loth, A Catalogue of the Arabic Manuscripts in the Library of the India Office (London, 1877), Vol. I, Preface.] They are today regarded as a valuable portion of the Library's Persian and Arabic collections.

C. The Art CollectionsThe art collections of the Library consist of four large groups: (a) Indian miniatures; (b) Persian miniatures; (c) paintings, drawings, and sketches of Indian subjects by British artists; and (d) natural-history drawings. Most of the Indian and a good proportion of the Persian miniatures are derived from the Johnson Collection, purchased by the Library in 1807 from Richard Johnson at the price of Gns. 500 for sixty-six albums of paintings and drawings and Gns. 2,500 for the Persian manuscripts.122 [Arnold, op. cit., p. 11.]

Johnson went out to India in 1770 as a writer in the East India Company, and although he was not a success in the various posts he filled over a period of twenty years, his stay in such places as Calcutta, Lucknow, and Hyderabad gave him splendid opportunities for collecting a great number of illustrated manuscripts and over a thousand paintings and drawings. Most of the works of art contained in the albums (which were broken up and each picture separately mounted in 1949) were executed by Indian artists of the late Moghul period, though some by Mohammedan painters represent the Persian school. Apart from a few pictures of miscellaneous character, the majority of these paintings and drawings are examples of the portrait art of the Moghul court, some of them very fine, being in the best tradition of the Moghul school of painting; others are representations of the Hindu mythological and raga-mala (Hindu musical modes) themes.123 [H. N. Randle, "Note on the India Office Ragamala Collection," New Indian Antiquary, VI, No. 5 (1941), 162-73.] In addition to the Persian miniatures included in the Johnson Collection, there are some two thousand miniatures in the Library's illustrated Persian manuscripts. The earliest of these is a collection of six diwans dating from 1313-15. There are many manuscripts containing Shiraz work of the sixteenth century, including a large and extremely sumptuous shahnamah formerly the property of Warren Hastings. There are also some fine examples of the seventeenth-century Isfahan style. A catalog of all the Persian miniatures is being prepared for publication.

Drawings of Indian subjects by British artists form a mixed collection of some eight thousand drawings varying greatly in quality. Some are by amateur artists who worked in India in different walks of life; many others of high artistic value are by professional artists, including some two hundred drawings, all recent purchases, by Thomas and William Daniell, uncle and nephew, famous for the work they did in India at the end of the eighteenth century. The main interest of this collection, however, is historical, the majority of the pictures depicting Indian scenery and landscapes, early townships, architecture and archeological remains, customs and occupations of the Indian people, as well as the life of the British servants of the East India Company in late-eighteenth- and early-nineteenth-century India. A catalog of the British drawings is ready for the press and is expected to be published in two volumes in the next year or two.

The collection of natural-history drawings in the Library consists of works mainly by Indian artists in British employment and some by British and Chinese painters. They are about five thousand in number and depict the flora and fauna of India and the adjoining territories of South and Southeast Asia.124 [For a detailed historical account and a description of the collection, see Mildred Archer, Natural History Drawings in the India Office Library (London: H. M. Stationery Office, 1962).] The bulk of these collections was formed by officials of the East India Company, mostly doctors and engineers, who were assigned special duties of scientific investigation in addition to their normal work. Several fairly important private collections were also made by individuals, imbued with the late-eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century enthusiasm of the British for the study of natural history, whose curiosity had been excited by the unfamiliar animals, birds, insects, and plants they had come across in India. The interest of the East India Company in this kind of research was mainly for the economic advantages resulting from it, though such research was also encouraged for its own sake. For various reasons, such as the exploitation of forests, development of medicine, experimental horticulture, etc., a knowledge of botany was found necessary. Botanic gardens in various parts of India were therefore established by the Company as experimental stations with official superintendents in charge. The most famous and the largest of these was the one established near Calcutta in 1787. A vast collection of natural- history drawings was made there under the immediate inspection and guidance of William Roxburgh, superintendent from 1793 to 1813. Prior to his appointment in the Calcutta Botanic Gardens, he had been the Company's botanist in the Carnatic and had made a collection of five hundred drawings and descriptions, the duplicates of which had been sent on to the Company in London between 1791 and 1794. In Calcutta he first started by making a complete survey list of all the different species he could find. He then employed a group of expert Indian artists and gave them special training himself to draw each item on his list. This was done from fresh specimens collected for the purpose, and descriptions of them were made on the spot. By the end of his term, which lasted a full twenty years, Roxburgh had formed a collection of 2,542 drawings. Bound in 35 volumes and known as Roxburgh Icones, they are still preserved in the herbarium in Calcutta Gardens, while duplicates made by the same artists were sent to London and deposited in the Company's Library. The work of collecting new specimens and making drawings of them was continued by Roxburgh's successors all through the nineteenth century and contributed to further knowledge of Indian botany. Many of the first standard books on the subject were based on the collections of these drawings and descriptions made by Roxburgh and those who followed him.

As already mentioned, several such experimental centers were established by the Company in different parts of India, where research was carried out much in the same way, and collections of drawings made by Indian artists employed for the purpose along with descriptions and specimens were sent regularly to the Company's Library and Museum.

Drawings of birds and quadrupeds were made at the menagerie and aviary which Marquis Wellesley, governor-general of Fort William from 1798 to 1805, had established at Barrackpore, near Calcutta, in 1804 for the specific purpose of collecting "materials for a correct account of all the most remarkable quadrupeds and birds in the provinces subject to the British Government in India." 125 [Ibid., p. 30.] Francis Buchanan, surgeon on the staff of Marquis Wellesley, was placed in honorary charge of this institution. Here birds and quadrupeds were kept until very careful and detailed drawings of them had been made, again by Indian artists employed for the purpose, under the direct supervision of Buchanan and his successor, Brown. Though the menagerie did not function for more than four years, a large number of drawings of birds, mammals, and reptiles were made there and dispatched to the Company in London, along with lists and descriptions, and are known separately as the Buchanan Collection and the G. and B. Collections.

Several collections of natural-history drawings were also made by various officials of the East India Company who were sent on expeditions and surveys financed by the Company in different parts of India and its other possessions farther east in Sumatra, Java, and Penang and the adjacent countries of Nepal, Burma, Afghanistan, Siam, and Cochin China. Though they were planned mainly for investigation of trade and for political and administrative reasons, informative material gathered by these officials in the course of these surveys almost always included some on the natural history of those areas. Thus we find that among the large number of drawings of Indian topography and antiquities made by Colin Mackenzie's draughtsmen there are two volumes on the flora and fauna of South India, both of which are in the Library. Similarly, while carrying out surveys on behalf of the Company in various parts of India, Buchanan, a keen naturalist, succeeded in forming a large collection of drawings of minerals, flowers, birds, animals, insects, and fishes of those areas with the help of an expert team of Indian artists he took with him everywhere for the purpose. A volume of drawings of fishes, which formed part of this collection, with a book of notes, is preserved in the India Office Library. Other important collections made through special expeditions and surveys were those of T. Horsfield in Java and Banka between 1811 and 1819 and of G. Finlayson in Siam and Cochin China from 1821 to 1822. Two of Horsfield's collections -- one comprising 97 drawings of birds, mammals, and reptiles, and the other comprising 241 drawings of Javanese Lepidoptera and mosses -- and about 80 drawings from Finlayson's Collection are to be found in the Library.

The largest and the finest of the private natural-history collections in the Library is the Wellesley Collection. It consists of about 2,660 folios bound in many volumes and was purchased by the Library in 1866. Many of the drawings depicting birds, animals, insects, plants, and fishes were made expressly for Lord Wellesley by Calcutta artists, while others were presented to him by his "fellow enthusiasts" in India and by travelers and British administrators from farther east in Malaya, Penang, Sumatra, the Moluccas, and even Australia.

Another great collector and one of the most enthusiastic was Major General Hardwicke, of the Bengal Artillery, who was from 1773 to 1823 in the service of the East India Company. Of the vast number of drawings he accumulated, assisted by Indian and British artists, while engaged in his military duties, the majority are in the British Museum (Natural History), but about 96 depicting Indian birds are in the India Office Library. Some of his drawings were acquired from him by Lord Wellesley in India and are, therefore, to be found in the Wellesley Collection. In the Preface of the book (Illustrations of Indian Zoology [London, 1830- 35]) by J. E. Gray and T. Hardwicke, based mainly on the drawings from Hardwicke's collection, Gray explains "how they were made on the spot and chiefly from living specimens of animals, executed by English and native artists constantly employed for the purpose under his own immediate superintendance."

Other notable collections in the series acquired in the first half of the nineteenth century are those of Brian Houghton Hodgson (1800-94) in Nepal; E. Blyth (1810-75); Sir Stamford Raffles in Malaya, Java, and Sumatra; and J. Forbes Royle of Saharanpur Botanic Gardens in the United Provinces. Varying greatly in quality and style, the chief interest of all these natural history drawings is now more artistic and historical than scientific.

V. The Future

A. The India Office Library ControversySince independence, both India and Pakistan have pressed for the India Office Library to be transferred to the subcontinent for division between them.

The Indo-Pakistan legal claim is not simply to the India Office Library but to: (a) the old India Office building in which the Library is located, (b) the Library itself, (c) the India Office Records, (d) certain furniture, pictures, sculpture, and other objects, which were in the building at the time of independence. The main events in the development of this controversy are as follows.

It is known that in May, 1960, Lord Home (now Sir Alec Douglas-Home), at that time Commonwealth secretary, took the opportunity of the presence in London of Nehru and Field Marshal Ayub Khan at the Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Meeting to suggest to them certain proposals which would associate India and Pakistan with the management of the Library. Since then it has been reported in the Indian and Pakistani press that the three governments have agreed that, before considering these proposals, they should submit to judicial arbitration the question of who owns the Library. Press reports say that the terms of reference of the dispute to arbitration are being discussed by the three governments.

B. The Move to New PremisesMeanwhile it has become necessary to arrange for the India Office Library and the India Office Records to move to new premises. As already mentioned, the India Office Library and the Records moved to their present quarters in the former India Office building in Whitehall when that building was erected in 1867. In 1966, after almost a century, they will move to new premises now being prepared for them about a mile away. From a historical and sentimental point of view the move will inevitably be regretted by many scholars who have worked in the existing quarters. The Library is the largest and most comprehensive collection of research material in the world for every aspect of British-Indian historical studies. Researches in this field have thus been carried on hitherto, by scholars from many countries, in the very building from which, until the Act of Independence of 1947, the governance of India was conducted. Its corridors are hung with oil paintings illustrating the British connection with India, busts of former British administrators of India are to be found on every floor, and the India Office Library has for many years held an annual reception for its readers in the Council Chamber, where the secretary of state for India held his weekly council and which, moreover, has much of the furniture from the earlier Court Room of the East India Company. The Library has, however, long since outgrown its present quarters. Its collections have expanded enormously, and the number of readers has been steadily rising for many years. In the new building the space available for the Library and for the India Office Records will be more than three times the present space allotted to them, and there will be ample room for all the services which modern librarianship demands.

On the assumption that the Library and the Records will stay in the United Kingdom -- and it is only on this assumption that the present authorities can base their administration -- many new possibilities for future development come into view. The new building will have adequate and expertly organized facilities for microphotography and other forms of mechanical reproduction, and there is no doubt that this part of the Library's work will grow rapidly. It is also probable that the Library will extend its collections of photographic copies of important manuscript material of Indological interest in other British libraries or overseas, including the Indian subcontinent, perhaps exchanging microfilms on a large scale, a development that would benefit Indian studies in many centers. The new building will have not only sufficient reading-room space but also seminar rooms where students can meet for discussion. The Library has never itself initiated research. Since, however, Indologists and South and Southeast Asian experts from all over the world meet within its premises, there will be many fruitful possibilities in the new building for intellectual exchanges and for stimulating research programs. It is hoped also that the Library will be able to make more systematic efforts to acquire printed material bearing upon the wide field of Indian studies from all countries -- by purchase, by exchange, or by an operation parallel to the American Public Law 480 Program for acquiring the whole significant printed output of countries in South and Southeast Asia. There is bound also to be a fuller scholarly exploitation of the immense and hitherto only partially used source material in the India Office Records. Several new guides, catalogs and other aids for the records researcher are being prepared; and the intention is that when the Library and the Records move to the new building they will become more closely integrated than ever before.