by Adrian Plau

Wellcome Collection

August 9, 2022

https://wellcomecollection.org/articles ... AAAP0nyHTz

Wellcome’s Adrian Plau shares some of the stories behind the Asian palm-leaf manuscripts in our collections. He reveals how British colonialism impacted this special form of knowledge transmission and the challenges involved in unearthing each manuscript’s origins and how it came to be at Wellcome Collection.

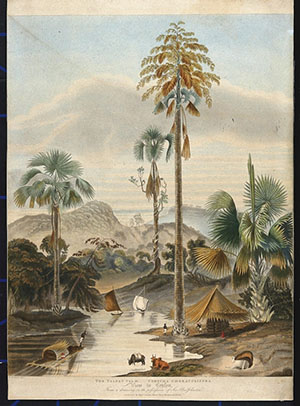

Colour print of the talipot palm (Corypha umbraculifera) growing by a lakeside in Sri Lanka. 'The talipot palm (Corypha umbraculifera).

Palm-leaf manuscripts are one of humanity’s most ancient and widespread technologies for transmitting and preserving knowledge in written form. They are made from two types of palms: palmyra and talipot, both found in South and Southeast Asia. Palmyra palms have an enormous range of uses, from mats and thatching to hats and fans, in addition to making palm-leaf manuscripts. The talipot palm lives for around 60 years but flowers only once. Death follows soon after its lone blossoming, but the leaves of the tree are cooked and dried and take on a second life. Inscribed with a stylus and rubbed with ink, they become palm-leaf manuscripts.

Novice Buddhist monks in orange robes cutting and sorting dried palm leaves for palm leaf manuscripts, Vat Manolom, Luang Prabang. Laos

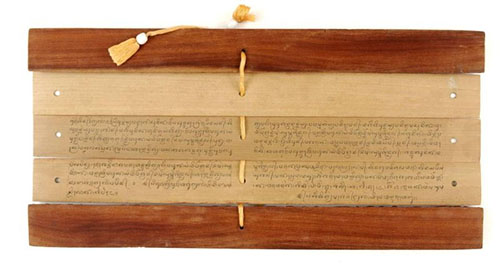

The process of turning palm leaves into manuscripts begins with the seasoning process, which helps prepare the palm leaves for long-term storage. First, branches are cut and completely dried in the sun. The dried and cut leaves are made into a roll tied with string. The rolls are boiled in water along with aloe vera pulp for about an hour to make them stronger. After being straightened and rolled to make them smooth, the leaves are cut into the proper shape and size, and a hole is made in the middle of each leaf to connect them together and make a palm-leaf volume.

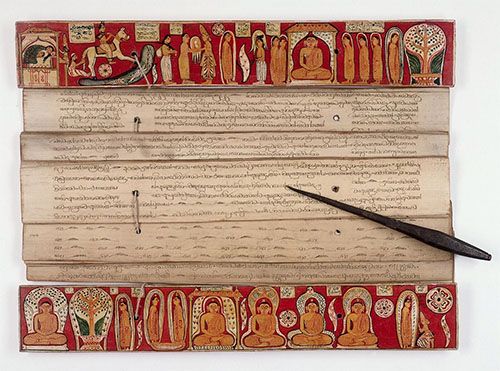

A Singhalese palm leaf manuscript with a brightly coloured painted wooden binding with images of the Buddha. The manuscript is open to reveal the inscribed text on the palm leaves. A black wooden stylus lays across the leaves.

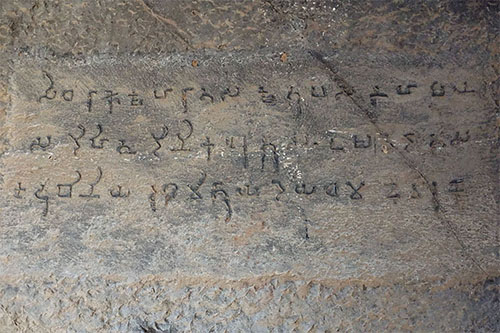

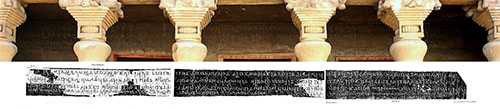

Measurement lines are drawn on the leaves as a guide to writing. The writing is done with a pen or brush stylus, by engraving or etching into the surface of the leaf. Dr Kalpana Sheth of Ahmedabad University, who has catalogued thousands of historic manuscripts for Wellcome Collection, notes that, “Writing on dried palm leaf is not easy. It needs proper pressure and technique. Once a mistake is made, it can never be corrected.” Once both sides of the leaf have been inscribed, black colouring is applied to make the incisions more visible. Dr Sheth adds, “Sometimes the palm leaf is preserved and protected from insects by also applying a mixture of turmeric powder, mustard oil, neem powder, and camphor powder.”

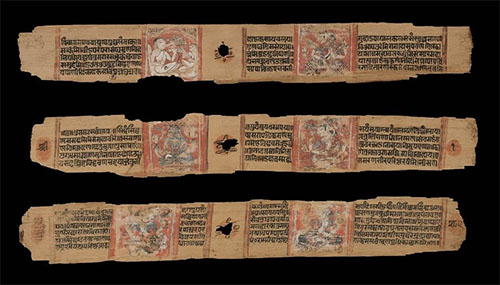

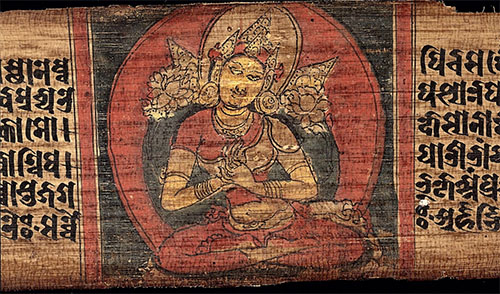

Detail of a palm leaf manuscript showing a brightly coloured painting of an incarnation of perfected wisdom in the form Prajnaparamita Devi with Sanskrit text on either side

Palm manuscripts displayed in Western museums for their visitors tend to be ancient and lavishly illustrated. For example, this manuscript, labelled prosaically as MS Indic Epsilon 1, is one of the rarest, most valuable items in Wellcome Collection. The manuscript is a copy of the Mahāyāna Buddhist treatise ‘Aṣṭasāhasrikā Prajñāpāramitā Sūtra’ (‘A Treatise on the Perfection of Wisdom in Eight Thousand Verses’) and does indeed feature several beautiful illustrations of Bodhisattvas, deities, and episodes from the Buddha’s life. The image shows an incarnation of perfected wisdom in the form of Prajñāpāramitā Devi. The manuscript was purchased by Dr Paira Mall, a Punjab-born physician who acquired many items for Henry Wellcome in India.

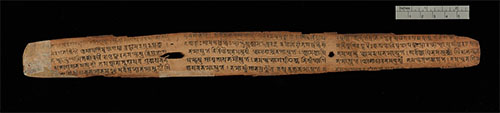

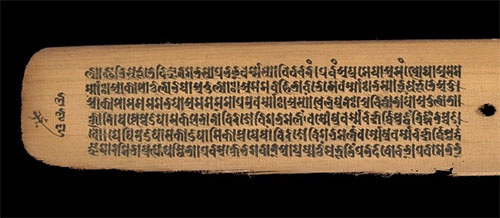

Detail from a palm leaf manuscript page showing text in sanskrit/bhujimol script. Heavy black text read horizontally on yellow palm leaf background

Palm-leaf manuscripts offer intriguing clues into how knowledge was disseminated and exchanged over time and through the many languages and kingdoms of South Asia. The scribe who copied Epsilon 1 presents himself as a man named Jivadhara, based in Nalanda (in the modern-day state of Bihar in northern India), the world’s first residential university and one of the ancient world’s prime centres of learning. But the manuscript uses the Bhujimol script used in Nepal, which is not typically found in Nalanda manuscripts from the 11th century.

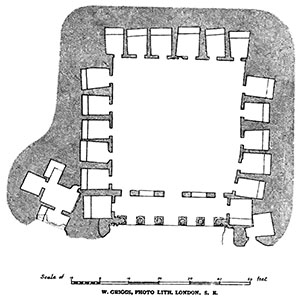

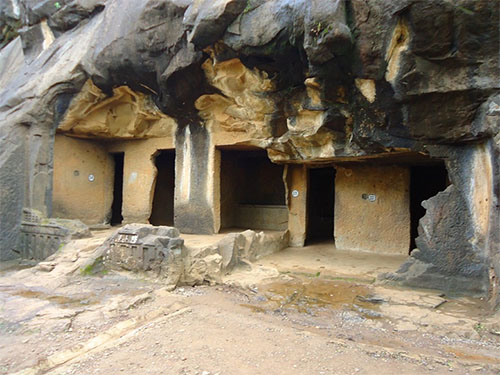

According to Taranatha, Asoka, the great Mauryan emperor of the third century BC, gave offerings to the chaitya of Sariputra that existed at Nalanda and erected a temple here; Ashoka must therefore be regarded as the founder of the Nalanda-vihara [university] [mahavihara].[!!!]6 The same authority adds that Nagarjuna, the famous Mahayana philosopher and alchemist of about the second century AD, began his studies at Nalanda and later on became the high priest here. It is also added that Suvishnu, a Brahmana contemporary of Nagarjuna, built one hundred and eight temples at Nalanda to prevent the decline of both the Hinayana and Mahayana schools of Buddhism.7 Taranatha also connects Aryadeva, a philosopher of the Madhyamika school of Buddhism of the early fourth century AD, with Nalanda.4

These statements of Taranatha would lead one to believe that Nalanda was a famous centre of Buddhism already at the time of Nagarjuna and continued to be so in the following centuries. But it may be clearly emphasised that the excavations have not revealed anything which suggests the occupation of the site before the Guptas, the earliest datable finds being a (forged) copper plate of Samudra-gupta and a coin of Kumaragupta.

-- Nalanda Mahavihara: Victim of a Myth regarding its Decline and Destruction, by O.P. Jaiswal

The German translation of Lama Taranatha's first book on India called The Mine of Previous Stones (Edelsteinmine) was made by Prof. Gruenwedel the reputed Orientalist and Archaeologist on Buddhist culture in Berlin. The translation came out in 1914 A.D. from Petrograd (Leningrad).

The German translator confessed his difficulty in translating the Tibetan words on matters relating to witchcraft and sorcery. So he has used the European terms from the literature of witchcraft and magic of the middle ages viz. 'Frozen' and 'Seven miles boots.'

He said that history in the modern sense could not be expected from Taranatha. The important matter with him was the reference to the traditional endorsement of certain teaching staff. Under the spiritual protection of his teacher Buddhaguptanatha, he wrote enthusiastically the biography of the predecessor of the same with all their extravagances, as well as the madness of the old Siddhas.

The book contains a rigmarole of miracles and magic….

-- Mystic Tales of Lama Taranatha: A Religio-Sociological History of Mahayana Buddhism, by Lama Taranatha

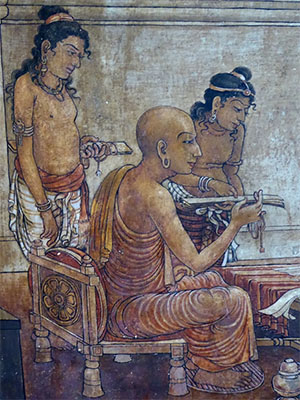

A seated Buddhist monk examines a palm leaf manuscript, as two young men, both standing, join him. One has another palm leaf manuscript in his hand. Detail of Kelaniya Temple painting.

Scholar Eva Allinger argues that Epsilon 1 dates from the 12th century and was copied in Nepal, not Nalanda. We don’t know who the Nepali scribe was or who might have commissioned and paid for what clearly was an expensive and complicated project. However, it is tempting to speculate that the owner wanted something with the splendour and prestige associated with Nalanda, yet readable Bhujimol. The world of manuscripts is nothing if not full of adaptation.

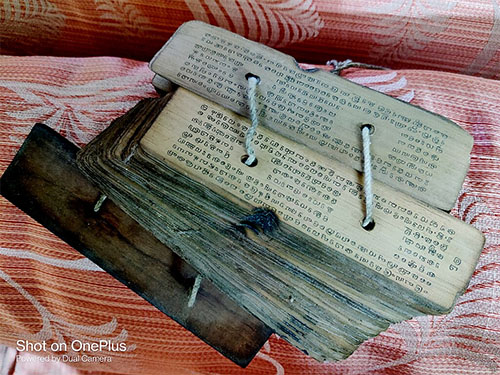

Three palm leaf manuscripts on a plain background. The one at the back is tall, stacked and bundled with string, the middle one is the longest and show open with just a couple of leaves. The one in front is the shortest in length and shown slightly splayed with a string going through it that emerges from the top and coils in front of the manuscript

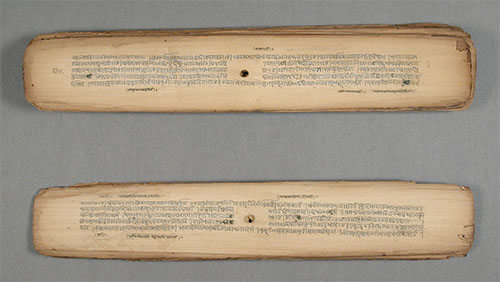

While the illustrations in Epsilon 1 and similar palm-leaf manuscripts are beautiful, they are spread over 208 leaves, only six of which contain illustrations. Palm manuscripts were not intended for display; most were for more everyday use – the equivalent of paperbacks rather than coffee-table books. Like paperbacks, they come in all shapes and sizes and can be just as rare and valued.

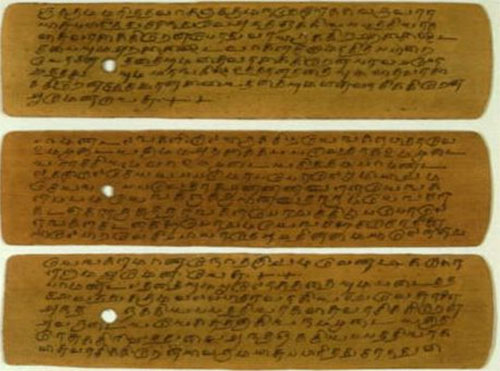

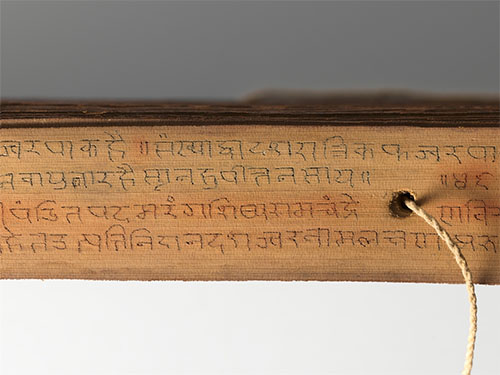

Detail of a strip from a palm leaf manuscript showing text inscribed in Hindi and a string connecting all the leaves emerging from a hole in the strip

MS Hindi 39.01 is a case in point. It is the only palm-leaf manuscript in Wellcome Collection written in Hindi. Made in 1763, it is a copy of Ramchand’s ‘Ramvinod’(‘Ram’s Pleasures’), an early modern medical treatise that was extremely popular across north India and beyond. This copy was completed about 100 years after Ramchand’s original [1763], finished in 1663.

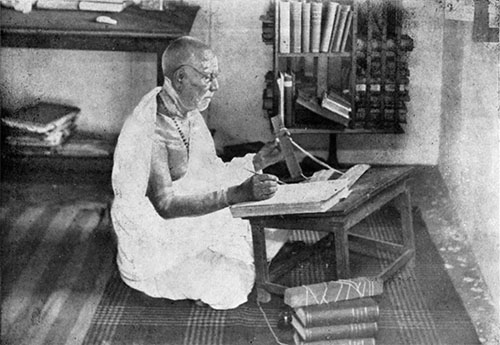

An old indian man (possibly a Hindu priest) sits cross-legged on the floor with a low writing desk in front of him, he reading a palm leaf manuscript in one hand and holding a pen over a paper book in the other, The room behind him had books and manuscripts on shelves and sideboards

Palm-leaf manuscripts demonstrate how knowledge was disseminated, adapted and modified through centuries of copying and translating texts such as Ramchand’s medical treatise. They also challenge imperialist notions of a timeless, unchanging South Asia where history began with European colonisation. Far from being timeless, ancient practices such as Ayurveda continued to develop through physicians such as Ramchand and Nainsukh, and the many copies of their works, such as MS Hindi 39.01, that have been made and circulated into modern times.

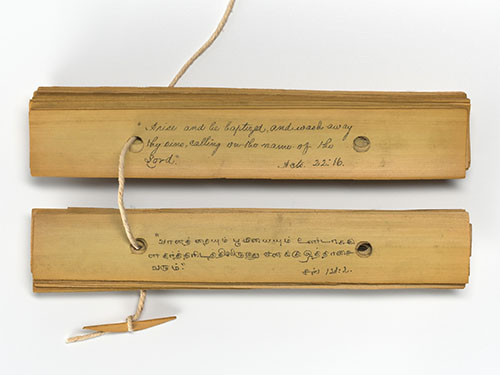

An open palm leaf manuscript showing two pages, one in English and one in Tamil. The leaves of the manuscript and connected by a string passing through a hole piercing all of the leaves. The end of the string is fastened to a small wooden peg. The English text says 'Arise and be baptized and wash away the sins calling out the names of the Lord. Acts 2.2:16'

A striking example of how palm-leaf manuscripts were adapted through colonialism is a Tamil manuscript, MS Tamil 3. According to its colophon, the manuscript was made by the scribe M Vethamanikam at the Nagercoil Seminary in the South Indian Kingdom of Travancore. The seminary at Nagercoil (now a city in Tamil Nadu) was established in the early 19th century by British missionaries. MS Tamil 3 contains a range of brief quotations from the Christian Bible, first in Tamil script and then in English translation on the flip side of each leaf. In this, it demonstrates both the continuing tradition of palm-leaf manuscripts, and how such local practices and traditions could be used for colonial purposes.

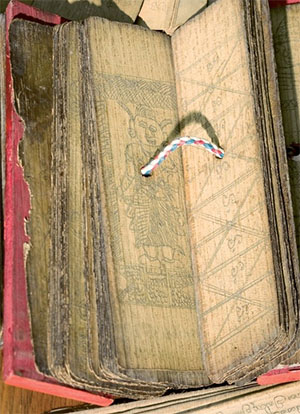

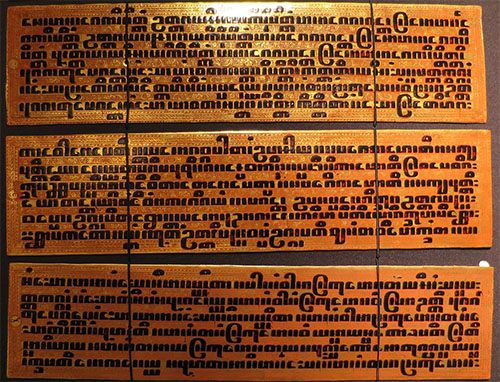

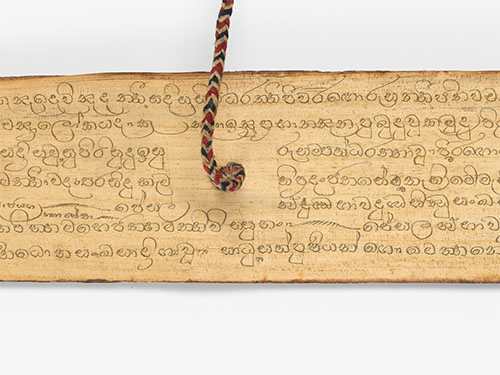

Detail of a page from a palm leaf manuscript with inscribed text in Sinhala. A red, white and blue string emerges from a hole in the centre of the leaf, holding the manuscript together.

MS Sinhala 91 and MS Sinhala 92 are Sri Lankan manuscripts that give further testament to the imprint of British colonialism on the palm-leaf manuscript tradition. They were created by two Buddhist monks, (signified by the thera honorific in the texts). While both manuscripts use the same eight-line astaka format of praise poetry and feature paraphrases in Sinhala, one is written in Sanskrit and the other in Pali. Both are addressed to Sir John Frederick Dickson (1835–91), who spent 25 years as a British colonial administrator in Sri Lanka. Dickson was fascinated by Buddhism and learned to read Pali. The quite generic phrases suggest that these manuscripts were commissioned by Dickson himself.

Black and white photograph in an album of Henry Wellcome and friends visiting the Gebel Moya archaeological site in Sudan, 1910-1911

The presence of the palm-leaf manuscripts in Wellcome Collection is itself a tangible imprint of British imperialism across Asia. Collectors such as Henry Wellcome had the wealth and privilege to buy more or less everything they wanted to acquire, and the global inequalities of colonial rule enabled them to do so. We are working to retrace the stories of how these items came into the collection, but this is by no means a straightforward task. For example, of the 11 Javanese manuscripts in the collection,we know that six were bought at auction in London between 1916 and 1934, but so far, we do not know how the other five came to Wellcome. And in the process of conducting an inventory of all our manuscript collections, we’ve found a 12th, uncatalogued Javanese manuscript.

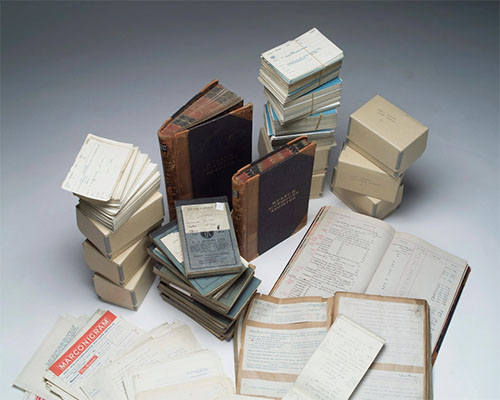

A selection of bound ledgers, registers, notebooks, cataloguing cards and correspondence containing historical records of the acquisition of items for the Wellcome Medical Museum and Library

By conducting this inventory, researching the histories of the items (this is just a small sample of the historical acquisition records at Wellcome Collection), and updating our cataloguing information, we strive to make it easier to find and access the manuscripts in our collections. Where possible, we are also working to digitise and transcribe manuscripts to make them more widely accessible to audiences around the world. Revealing the stories behind objects in Wellcome Collection and how they came to be in the collections is going to be a long process, but we’ve taken the first steps.

Adrian Plau is Manuscript Collections Information Analyst at Wellcome Collection, and a recent Headley Fellow with the Art Fund. He holds a PhD in South Asia Studies from SOAS.