by Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/15/24

Naneghat Cave and Inscriptions

Naneghat geography and inscriptions

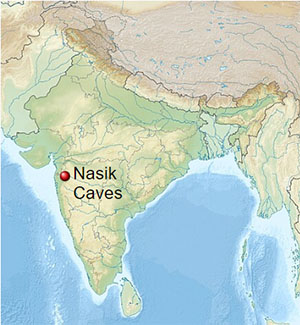

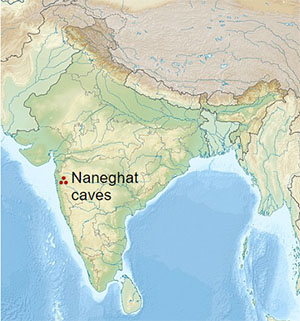

Naneghat caves shown within India

Alternative name: Nanaghat caves

Location: Maharashtra, India

Region: Western Ghats

Coordinates: 19°17′31.0″N 73°40′33.5″E

Altitude: 750 m (2,461 ft)

Type: Caves, trade route passage

History

Builder: Queens, Satavahana dynasty -Naganika

Material: Natural rock

Founded: 2nd-century BCE

Cultures: Hinduism [1]

Management: Archaeological Survey of India

Naneghat, also referred to as Nanaghat or Nana Ghat (IAST: Nānāghaṭ), is a mountain pass in the Western Ghats range between the Konkan coast and the ancient town of Junnar in the Deccan plateau. The pass is about 120 kilometres (75 mi) north of Pune and about 165 kilometres (103 mi) east from Mumbai, Maharashtra, India.[2] It was a part of an ancient trading route, and is famous for a major cave with Sanskrit inscriptions in Brahmi script and Middle Indo-Aryan dialect.[3] These inscriptions have been dated between the 2nd and the 1st century BCE, and attributed to the Satavahana dynasty era.[4][5][6] The inscriptions are notable for linking the Vedic and Hinduism deities, mentioning some Vedic srauta rituals and of names that provide historical information about the ancient Satavahanas.[5][7] The inscriptions present the world's oldest numeration symbols for "2, 4, 6, 7, and 9" that resemble modern era numerals, more closely those found in modern Nagari and Hindu-Arabic script.[6][8][9]

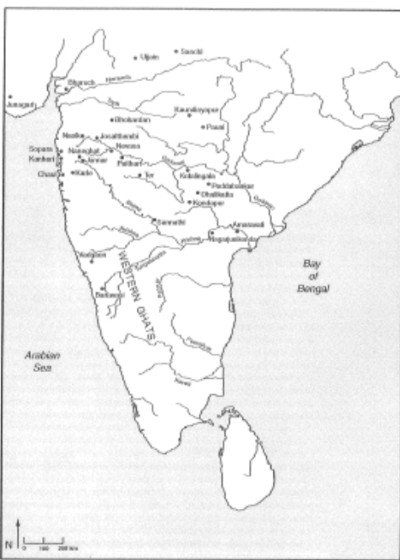

Location

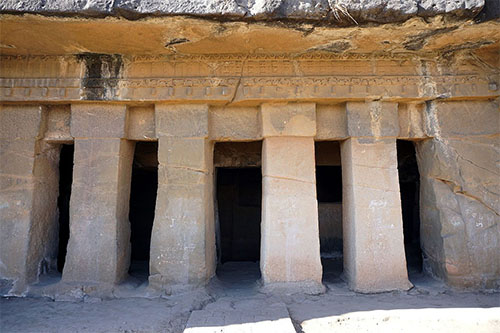

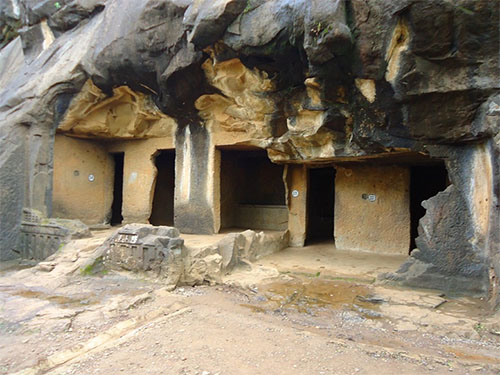

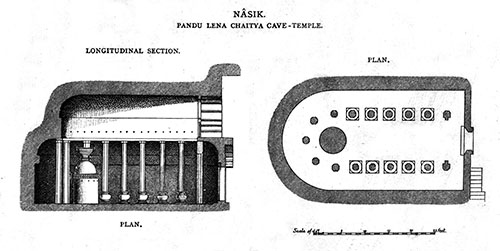

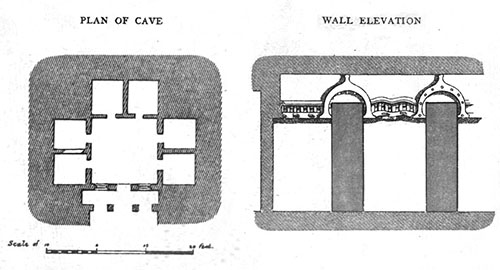

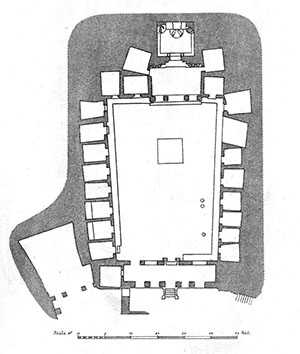

Nanaghat pass stretches over the Western Ghats, through an ancient stone laid hiking trail to the Nanaghat plateau. The pass was the fastest key passage that linked the Indian west coast seaports of Sopara, Kalyan and Thana with economic centers and human settlements in Nasik, Paithan, Ter and others, according to Archaeological Survey of India.[10] Near the top is a large, ancient manmade cave. On the cave's back wall are a series of inscriptions, some long and others short. The high point and cave is reachable by road via Highways 60 or 61. The cave archaeological site is about 120 kilometres (75 mi) north of Pune and about 165 kilometres (103 mi) east from Mumbai.[2] The Naneghat Cave is near other important ancient sites. It is, for example, about 35 kilometres (22 mi) from the Lenyadri Group of Theravada Buddhist Caves and some 200 mounds that have been excavated near Junnar, mostly from the 3rd-century BCE and 3rd-century CE period. The closest station to reach Naneghat is Kalyan station which lies on the Central Line.[10]

History

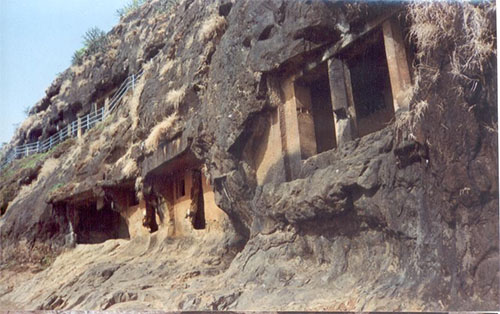

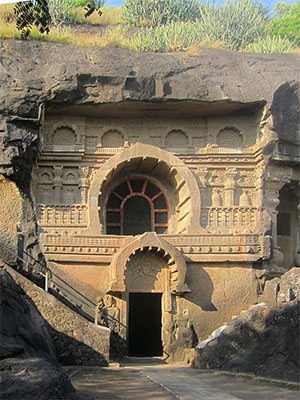

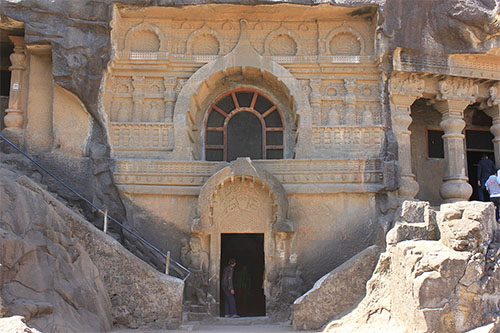

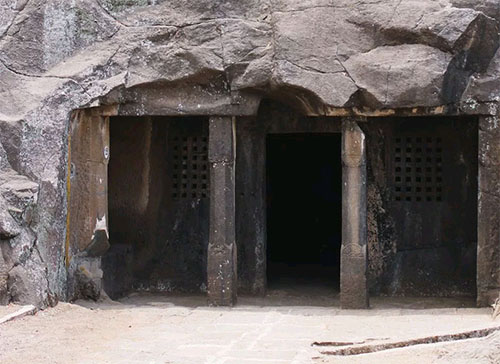

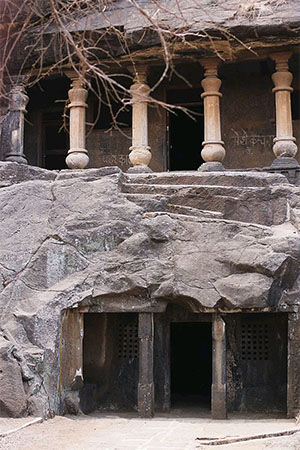

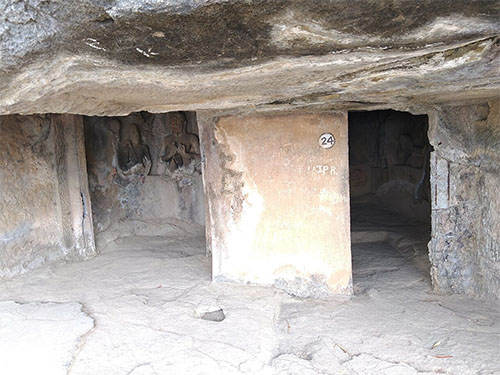

The Naneghat caves, likely an ancient rest stop for travellers.[11]

During the reign of the Satavahana (c. 200 BCE – 190 CE), the Naneghat pass was one of the trade routes. It connected the Konkan coast communities with Deccan high plateau through Junnar.[2] Literally, the name nane means "coin" and ghat means "pass". The name is given because this path was used as a tollbooth to collect toll from traders crossing the hills. According to Charles Allen, there is a carved stone that from a distance looks like a stupa, but is actually a two-piece carved stone container by the roadside to collect tolls.[12]

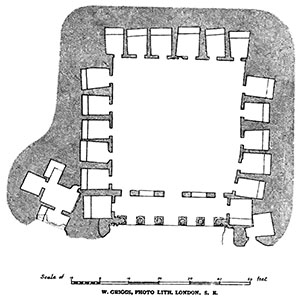

The scholarship on the Naneghat Cave inscription began after William Sykes found them while hiking during the summer of 1828.[13][14] Neither an archaeologist nor epigraphist, his training was as a statistician and he presumed that it was a Buddhist cave temple. He visited the site several times and made eye-copy (hand drawings) of the script panel he saw on the left and the right side of the wall. He then read a paper to the Bombay Literary Society in 1833 under the title, Inscriptions of the Boodh caves near Joonur,[13] later co-published with John Malcolm in 1837.[15] Sykes believed that the cave's "Boodh" (Buddhist) inscription showed signs of damage both from the weather elements as well as someone crudely incising to desecrate it.[12] He also thought that the inscription was not created by a skilled artisan, but someone who was in a hurry or not careful.[12] Sykes also noted that he saw stone seats carved along the walls all around the cave, likely because the cave was meant as a rest stop or shelter for those traveling across the Western Ghats through the Naneghat pass.[11][12][13]

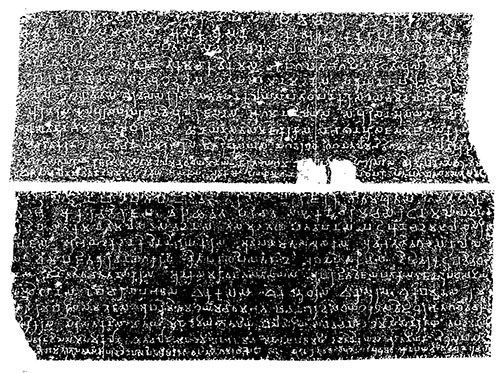

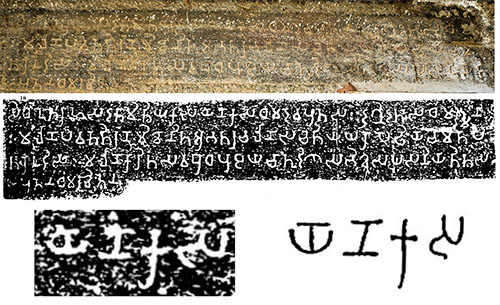

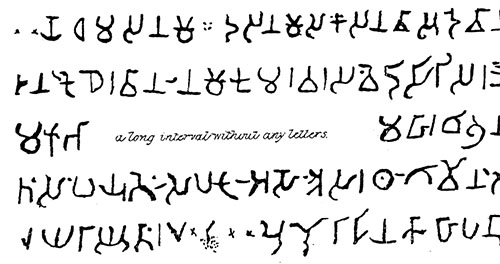

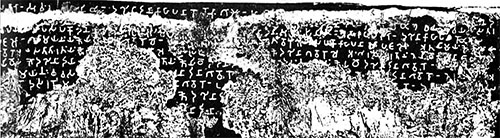

William Sykes made an imperfect eye-copy of the inscription in 1833, to bring it to scholarly attention.[16]

Sykes proposed that the inscription were ancient Sanskrit because the statistical prevalence rate of some characters in it was close to the prevalence rate of same characters in then known ancient Sanskrit inscriptions.[13][17] This suggestion reached the attention of James Prinsep, whose breakthrough in deciphering Brahmi script led ultimately to the inscription's translation. Much that Sykes guessed was right, the Naneghat inscription he had found was indeed one of the oldest Sanskrit inscriptions.[12] He was incorrect in his presumption that it was a Buddhist inscription because its translation suggested it was a Hindu inscription.[1] The Naneghat inscription were a prototype of the refined Devanagari to emerge later.[12]

Georg Bühler published the first version of a complete interpolations and translation in 1883.[18] He was preceded by Bhagvanlal Indraji, who in a paper on numismatics (coins) partially translated it and remarked that the Naneghat and coin inscriptions provide insights into ancient numerals.[18][19]

Date

Naneghat Pass Entrance

The inscriptions are attributed to a queen of the Satavahana dynasty. Her name was either Nayanika or Naganika, likely the wife of king Satakarni. The details suggest that she was likely the queen mother, who sponsored this cave after the death of her husband, as the inscription narrates many details about their life together and her son being the new king.[5]

The Naneghat cave inscriptions have been dated by scholars to the last centuries of the 1st millennium BCE. Most scholars date it to the early 1st-century BCE, some to 2nd-century BCE, a few to even earlier.[4][5][6] Sircar dated it to the second half of the 1st-century BCE.[20] Upinder Singh and Charles Higham date 1st century BCE.[21][22]

The Naneghat records have proved very important in establishing the history[???] of the region. Vedic Gods like Dharma Indra, Chandra and Surya are mentioned here. The mention of Samkarsana (Balarama) and Vasudeva (Krishna) indicate the prevalence of Bhagavata tradition of Hinduism in the Satavahana dynasty.

Nanaghat inscriptions

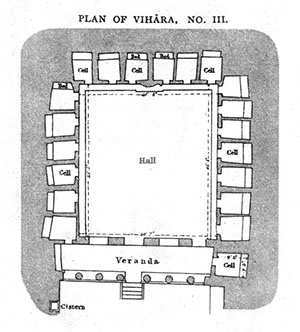

Two long Nanaghat inscriptions are found on the left and right wall, while the back wall has small inscriptions on top above where the eight life-sized missing statues would have been before somebody hacked them off and removed them.[12]

Left wall

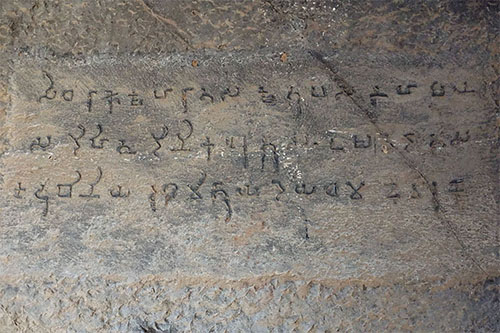

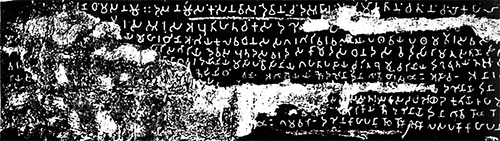

Left wall inscription, Brahmi script

Inscription

1. sidhaṃ ... no dhaṃmasa namo īdasa namo saṃkaṃsana-vāsudevānaṃ caṃda-sūtānaṃ mahimāvatānaṃ catuṃnaṃ caṃ lokapālānaṃ yama-varuna-kubera-vāsavānaṃ namo kumāravarasa vedisirisa raño

2. ......vīrasa sūrasa apratihatacakasa dakhināpaṭhapatino raño simukasātavāhanasa sunhāya ......

3. mā ..... bālāya mahāraṭhino aṃgiya-kulavadhanasa sagaragirivaravalayāya pathaviya pathamavīrasa vasa ... ya va alaha ......salasu ..ya mahato maha ...

4. .... sātakaṇi sirisa bhāriyā devasa putadasa varadasa kāmadasa dhanadasa vedisiri-mātu satino sirimatasa ca mātuya sīma .... pathamaya .....

5. variya ....... ānāgavaradayiniya māsopavāsiniya gahaṭāpasāya caritabrahmacariyāya dikhavratayaṃñasuṃḍāya yañāhutādhūpanasugaṃdhāya niya .......

6. rāyasa ........ yañehi yiṭhaṃ vano | agādheya-yaṃño dakhinā dinā gāvo bārasa 12 aso ca 1 anārabhaniyo yaṃño dakhinā dhenu .........

7. ...... dakhināya dinā gāvo 1700 hathī 10 .....

8. ......... as ..... sasataraya vāsalaṭhi 289 kubhiyo rupāmayiyo 17 bhi ......

9. .......... riko yaṃño dakhināyo dinā gāvo 11,000 asā 1,000 pasapako ..............

10. ............. 12 gamavaro 1 dakhinā kāhāpanā 24,400 pasapako kāhāpanā 6,000 | rājasūya-yaṃño ..... sakaṭaṃ

The missing characters do not match the number of dots; Bühlerpublished a more complete version.[18]

Left wall translation without interpolation

Samkasana ([x]) and Vāsudeva ([x]) in the Naneghat cave inscription

Dakṣiṇā or Dakshina (Sanskrit: दक्षिणा) is a Sanskrit word found in Hinduism, Buddhism, Sikh and Jain literature where it may mean any donation, fees or honorarium given to a cause, monastery, temple, spiritual guide or after a ritual. It may be expected, or a tradition or voluntary form of dāna. The term is found in this context in the Vedic literature. It may mean honorarium to a guru for education, training or guidance.

According to Monier Williams, the term is found in many Vedic texts, in the context of "a fee or present to the officiating priest (consisting originally of a cow, Kātyāyana Śrautasūtra 15, Lāṭyāyana Śrautasūtra 8.1.2)", a 'donation to the priest', a 'reward', an 'offering to a guru', a 'gift, donation'.

-- Daksina, by Wikipedia

Agnyādheya (अग्न्याधेय) refers to one of the seven Haviḥsaṃsthās or Haviryajñas (groups of seven sacrifices).—Hārīta says: “Let a man offer the Pākayajñas always, always also the Haviryajñas, and the Somayajñas (Soma sacrifices), according to rule, if he wishes for eternal merit”.—The object of these sacrifices [viz., Agnyādheya] is eternal happiness, and hence they have to be performed during life at certain seasons, without any special occasion (nimitta), and without any special object (kāma). According to most authorities, however, they have to be performed during thirty years only. After that the Agnihotra only has to be kept up.

-- Sacred Texts: The Grihya Sutras, Part 2 (SBE30)

***

Agnyādheya (अग्न्याधेय) refers to the ritual of “kindling the sacred fire” and represents one of the various rituals mentioned in the Vaikhānasagṛhyasūtra (viz., vaikhānasa-gṛhya-sūtra) which belongs to the Taittirīya school of the Black Yajurveda (kṛṣṇayajurveda).—The original Gṛhyasūtra of Vaikhanāsa consists of eleven chapters or “praśnas”. Each praśna is subdivided into sub-divisions called “khaṇḍa”. But only the first seven chapters deal with actual Gṛhyasūtra section. Agnyādheya is one of the seven haviryajñas.

-- Shodhganga: Vaikhanasa Grhyasutra Bhasya (Critical Edition and Study)

1. Sidham[note 1] to Dharma, adoration to Indra, adoration to Samkarshana and Vāsudeva,[note 2] the descendants of the Moon ("Chandra") endowed with majesty, and to the four guardians of the world ("Lokapalas"), Yama, Varuna, Kubera and Vāsava; praise to Vedisri, the best of royal princes (kumara)![note 3] Of the king.

2. .... of the brave hero, whose rule is unopposed, the Dekhan......

3. By ..... the daughter of the Maharathi, the increaser of the Amgiya race, the first hero of the earth that is girdled by the ocean and the best of mountains....

4. wife of . . . Sri, the lord who gives sons, boons, desires and wealth, mother of Yedisri and the mother of the illustrious Sakti.....

5. Who gave a . . . most excellent nagavaradayiniya,[note 4] who fasted during a whole month, who in her house an ascetic, who remained chaste, who is well acquainted with initiatory ceremonies, vows and offerings, sacrifices, odoriferous with incense, were offered......

6. O the king ........ sacrifices were offered. Description - An Agnyadheya sacrifice, a dakshina[note 5] was offered twelve, 12, cows and 1 horse; - an Anvarambhaniya sacrifice, the dakshina, milch-cows.....

7. ...... dakshina were given consisting of 1700 cows, 10 elephants,

8. .... 289.....17 silver waterpots.....

9. ..... a rika-sacrifice, dakshina were given 11,000 cows, 1000 horses

10. ......12 . . 1 excellent village, a dakshina 24,400 Karshapanas, the spectators and menials 6,001 Karshapanas; a Raja ........ the cart[26]

Left wall translation with interpolation

Naneghat deities

The two deities Samkarshana and Vāsudeva on the coinage of Agathocles of Bactria, circa 190-180 BCE.[27][28]

1. [Om adoration] to Dharma [the Lord of created beings], adoration to Indra, adoration to Samkarshana and Vāsudeva, the descendants of the Moon (who are) endowed with majesty, and to the four guardians of the world, Yama, Varuna, Kubera and Vasava; praise to Vedisri, the best of royal princes! Of the king.

2. .... of the brave hero, whose rule is unopposed, (of the lord of) the Dekhan......

3. By ..... the daughter of the Maharathi, the increaser of the Amgiya race, the first hero of the earth that is girdled by the ocean and the best of mountains....

4. (who is the) wife of . . . Sri, the lord who gives sons, boons, (the fulfillment of) desires and wealth, (who is the) mother of Yedisri and the mother of the illustrious Sakti.....

5. Who gave a . . . most excellent (image of) a snake (deity), who fasted during a whole month, who (even) in her house (lived like) an ascetic, who remained chaste, who is well acquainted with initiatory ceremonies, vows and offerings, sacrifices, odoriferous with incense, were offered......

6. O the king ........ sacrifices were offered. Description - An Agnyadheya sacrifice (was offered), a dakshina was offered (consisting of) twelve, 12, cows and 1 horse; - an Anvarambhaniya sacrifice (was offered), the dakshina (consisted of) , milch-cows.....

7. ...... dakshina were given consisting of 1700 cows, 10 elephants,

8. .... (289?).....17 silver waterpots.....

9. ..... a rika-sacrifice, dakshina were given (consisting of) 11,000 cows, 1000 horses

10. ......12 . . 1 excellent village, a dakshina (consisted of) 24,400 Karshapanas, (the gifts to) the spectators and menials (consisted of) 6,001 Karshapanas; a Raja [suya-sacrifice] [Purushamedha]........ the cart[26]

Right wall

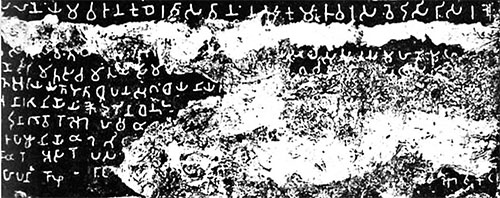

Right wall inscription, Brahmi script

Inscription

1. ..dhaṃñagiritaṃsapayutaṃ sapaṭo 1 aso 1 asaratho 1 gāvīnaṃ 100 asamedho bitiyo yiṭho dakhināyo dinā aso rupālaṃkāro 1 suvaṃna ..... ni 12 dakhinā dinā kāhāpanā 14,000 gāmo 1 haṭhi ........ dakhinā dinā

2. gāvo ... sakaṭaṃ dhaṃñagiritaṃsapayutaṃ ...... ovāyo yaṃño ..... 17 dhenu .... vāya +satara sa

3. ........... 17 aca .... na ..la ya ..... pasapako dino ..... dakhinā dinā su ... pīni 12 tesa rupālaṃkāro 1 dakhinā kāhāpanā 10,000 ... 2

4. ......gāvo 20,000 bhagala-dasarato yaṃño yiṭho dakhinā dinā gāvo 10,000 | gargatirato yaño yiṭho dakhinā ..... pasapako paṭā 301 gavāmayanaṃ yaṃño yiṭhodakhinā dinā gāvo 1100 | .............. gāvo 1100 pasapako kāhāpanā +paṭā 100 atuyāmo yaṃño .....

5. ........ gavāmayanaṃ yaño dakhinā dinā gāvo 1100 | aṃgirasāmayanaṃ yaṃño yiṭho dakhinā gāvo 1,100 | ta ............. dakhinā dinā gāvo 1100 | satātirataṃ yaṃño ........ 100 ......... yaño dakhinā gāvo 110 aṃgirasatirato yaṃño yiṭho dakhinā gāvo

6. ......... gāvo 1,002 chaṃdomapavamānatirato dakhinā gāvo 100 | aṃgirasatirato yaṃño yiṭho dakhinā ....... rato yiṭho yaño dakhinā dinā ....... to yaṃño yiṭho dakhinā ......... yaṃño yiṭho dakhinā dinā gāvo 1000 | ............

7. ......... na +sayaṃ .......... dakhinā dinā gāvo .......... ta ........ aṃgirasāmayanaṃ chavasa ........ dakhinā dinā gāvo 1,000 ........... dakhinā dinā gāvo 1,001 terasa ... a

8. ........ terasarato sa ......... āge dakhinā dinā gāvo ......... dasarato ma .......... dinā gāvo 1,001 u ........... 1,001 da ...........

9. ........ yaño dakhinā dinā .........

10. .......... dakhinā dinā ..........

The missing characters do not match the number of dots; Bühler published a more complete version.[18]

Right wall translation without interpolation

1. ...used for conveying a mountain of grain, 1 excellent dress, 1 horse, 1 horse-chariot, 100 kine. A second horse-sacrifice was offered; dakshina were given 1 horse with silver trappings, 12 golden...... an(other) dakshina was given 14,000 (?) Karshapanas, 1 village . . elephant, a dakshina was given

2. ....cows, the cart used for conveying a mountain of grain..... an..... Ovaya sacrifice.......... 17 milch cows (?)....

3. ........ 17 ....... presents to the spectators were given.... a dakshina was given 12..... 1 silver ornaments for them, a dakshina was given consisting of 10,000 Karshapanas............

4. ..... 20,000(?) cows ; a Bhagala-Dasharatha sacrifice was offered, a dakshina was given 10,001 cows; a Gargatriratra sacrifice was offered ...... the presents to the spectators and menials 301 dresses; a Gavamayana was offered, a dakshina was given 1,101 cows, a .... sacrifice, the dakshina 1,100 (?) cows, the presents to the spectators and menials . . Karshapanas, 100 dresses; an Aptoryama sacrifice .....

5. ..... ;a Gavamayana sacrifice was offered, a dakshina was given 1,101 cows; an Angirasamayana sacrifice was offered, a dakshina was given 1,101 cows; was given 1,101 cows; a Satatirata sacrifice ...... 100 ......... ; ......sacrifice was offered, the dakshina 1,100 cows; an Angirasatriratra sacrifice was offered; the dakshina .... cows ....

6. ........ 1,002 cows; a Chhandomapavamanatriratra sacrifice was offered, the dakshina .... ; a ....... ratra sacrifice was offered, a dakshina was given; a ...... tra sacrifice was offered, a dakshina ... ; a ..... sacrifice was offered, a dakshina was given 1,001 cows

7. .......... ; a dakshina was given ..... cows ........; an Angirasamayana, of six years ....... , a dakshina was given, 1,000 cows ..... was given 1,001 cows, thirteen ........

8. ........... a Trayoclasaratra ......... a dakshina was given, .... cows ......... a Dasaratra .... a ...... sacrifice, a dakshina was given 1,001 cows....

9. [29]

Right wall translation with interpolation

1. Used for conveying a mountain of grain, 1 excellent dress, 1 horse, 1 horse-chariot, 100 kine. A second horse-sacrifice was offered; dakshina were given (consisting of) 1 horse with silver trappings, 12 golden...... an(other) dakshina was given (consisting of) 14,000 (?) Karshapanas, 1 village . . elephant, a dakshina was given

2. ....cows, the cart used for conveying a mountain of grain..... an..... Ovaya sacrifice.......... 17 milch cows (?)....

3. ........ 17 ....... presents to the spectators were given.... a dakshina was given (consisting of) 12..... 1 (set of) silver ornaments for them, an(other) dakshina was given consisting of 10,000 Karshapanas............

4. ..... 20,000(?) cows ; a Bhagala-Dasharatha sacrifice was offered, a dakshina was given (consisting of) 10,001 cows; a Gargatriratra sacrifice was offered ...... the presents to the spectators and menials (consisted of) 301 dresses; a Gavamayana was offered, a dakshina was given (consisting of) 1,101 cows, a .... sacrifice, the dakshina (consisted of) 1,100 (?) cows, the presents to the spectators and menials (consisted of) . . Karshapanas, 100 dresses; an Aptoryama sacrifice (was offered).....

5. ..... ;a Gavamayana sacrifice was offered, a dakshina was given (consisting of) 1,101 cows; an Angirasamayana sacrifice was offered, a dakshina was given (of) 1,101 cows; (a dakshina) was given (consisting of) 1,101 cows; a Satatirata sacrifice ...... 100 ......... ; ......sacrifice was offered, the dakshina (consisted of) 1,100 cows; an Angirasatriratra sacrifice was offered; the dakshina (consisted of) .... cows ....

6. ........ 1,002 cows; a Chhandomapavamanatriratra sacrifice was offered, the dakshina .... ; a ....... ratra sacrifice was offered, a dakshina was given; a ...... tra sacrifice was offered, a dakshina ... ; a ..... sacrifice was offered, a dakshina was given (consisting of) 1,001 cows

7. .......... ; a dakshina was given (consisting of) ..... cows ........; an Angirasamayana, of six years (duration) ....... , a dakshina was given, (consisting of) 1,000 cows ..... (a sacrificial fee) was given (consisting of) 1,001 cows, thirteen ........

8. ........... a Trayoclasaratra ......... a dakshina was given, (consisting of) .... cows ......... a Dasaratra .... a ...... sacrifice, a dakshina was given (consisting of) 1,001 cows....

9. [29]

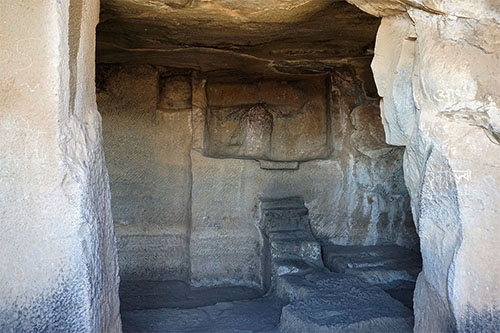

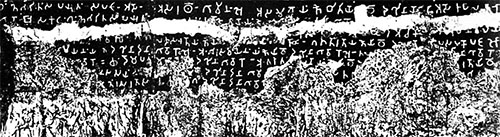

Back wall relief and names

Regnal inscriptions

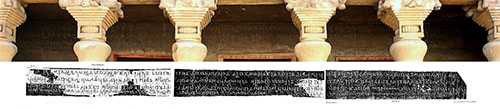

The back wall, with regnal inscriptions.

"Simuka" portion of the inscription (photograph and rubbing) in early Brahmi script:

[x]. Rāyā Simuka - Sātavāhano sirimato. "King Simuka Satavahana, the illustrious one"[30]

The back wall of the cave has a niche with eight life-size relief sculptures. These sculptures are gone, but they had Brahmi script inscriptions above them that help identify them.[21]

1. Raya Simuka - Satavahano sirimato

2. Devi-Nayanikaya rano cha

3. Siri-Satakanino

4. Kumaro Bhaya ........

5. (unclear)

6. Maharathi Tranakayiro.

7. Kumaro Hakusiri

8. Kumaro Satavahano

Reception and significance

The Nanaghat inscription has been a major finding. According to Georg Bühler, it "belongs to the oldest historical documents of Western India, are in some respects more interesting and important than all other cave inscriptions taken together".[16][24]

The inscription mentions both Balarama (Samkarshana) and Vāsudeva-Krishna, along with the Vedic deities of Indra, Surya, Chandra, Yama, Varuna and Kubera.[12] This provided the link between Vedic tradition and the Hinduism .[31][32][33] Given it is inscribed in stone and dated to 1st-century BCE, it also linked the religious thought in the post-Vedic centuries in late 1st millennium BCE with those found in the unreliable highly variant texts such as the Puranas dated to later half of the 1st millennium CE. The inscription is a reliable historical record, providing a name and floruit to the Satavahana dynasty.[12][32][11]

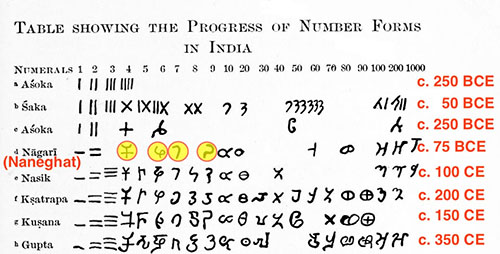

1911 sketch of numerals history in ancient India, with the Naneghat inscription shapes.

The Naneghat inscriptions have been important to the study of history of numerals.[9] Though damaged, the inscriptions mention numerals in at least 30 places.[34] They present the world's oldest known numeration symbols for "2, 4, 6, 7, and 9" that resemble modern era numerals, particularly the modern Nāgarī script.[6][35] The numeral values used in the Naneghat cave confirm that the point value had not developed in India by the 1st century BCE.[8][36]

The inscription is also evidence and floruit that Vedic ideas were revered in at least the northern parts of the Deccan region before the 1st-century BCE. They confirm that Vedic srauta sacrifices remained in vogue among the royal families through at least the 1st-century BCE.[31][7] The Naneghat cave is also evidence that Hindu dynasties had sponsored sculptures by the 1st-century BCE, and secular life-size murti (pratima) tradition was already in vogue by then.[11][37][note 6]

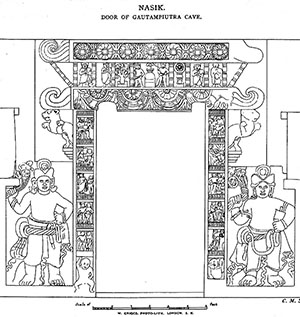

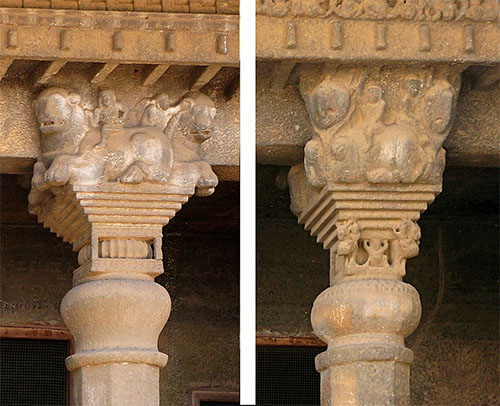

According to Susan Alcock, the Naneghat inscription is important for chronologically placing the rulers and royal lineage of the Satavahana Empire. It is considered on palaeographical grounds to be posterior to the Nasik Caves inscription of Kanha dated to 100-70 BCE. Thus, Naneghat inscription helps place Satakarni I after him, and Satavahanas as a Hindu dynasty whose royal lineage performed many Vedic sacrifices.[38]

See also:

• Hindu temple

• Kanheri Caves

Notes:

1. Variously translated to "Success" or "Om adoration"".[23][24]

2. Samkarshana and Vasudeva are synonyms for Balarama and Krishna.[25]

3. Kumaravarasa translated to "royal princes" or "Kartikeya".[18][25]

4. Buhler states that its translation is uncertain, can be either "who gave a most excellent image of a snake deity" or "who gave a most excellent image of an elephant deity" or "who gave a boon of a snake or elephant deity".[23]

5. variously translated as "sacrificial fee" or "donation".[18][12]

6. The eight statues were missing when William Sykes visited the cave in 1833.

References:

1. Theo Damsteegt 1978, p. 206.

2. Georg Bühler 1883, pp. 53–54.

3. Theo Damsteegt 1978, p. 206, Quote: "A Hinduist inscription that is written in MIA dialect is found in a Nanaghat cave. In this respect, reference may also be made to a MIA inscription on a Vaishnava image found near the village Malhar in Madhya Pradesh which dates back to about the same age as the Nanaghat inscription."; see also page 321 note 19.

4. Richard Salomon 1998, p. 144.

5. Upinder Singh 2008, pp. 381–384.

6. Development Of Modern Numerals And Numeral Systems: The Hindu-Arabic system, Encyclopaedia Britannica, Quote: "The 1, 4, and 6 are found in the Ashoka inscriptions (3rd century bce); the 2, 4, 6, 7, and 9 appear in the Nana Ghat inscriptions about a century later; and the 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and 9 in the Nasik caves of the 1st or 2nd century CE — all in forms that have considerable resemblance to today’s, 2 and 3 being well-recognized cursive derivations from the ancient = and ≡."

7. Carla Sinopoli 2001, pp. 168–169.

8. David E. Smith 1978, pp. 65–68.

9. Norton 2001, pp. 175–176.

10. Lenyadri Group of Caves, Junnar Archived 10 April 2009 at the Wayback Machine, Archaeological Survey of India

11. Vincent Lefèvre (2011). Portraiture in Early India: Between Transience and Eternity. BRILL Academic. pp. 33, 85–86. ISBN 978-9004207356.

12. Charles Allen 2017, pp. 169–170.

13. Shobhana Gokhale 2004, pp. 239–260.

14. Charles Allen 2017, p. 170.

15. John Malcolm and W. H. Sykes (1837), Inscriptions from the Boodh Caves, near Joonur, The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland, Vol. 4, No. 2, Cambridge University Press, pages 287-291

16. Georg Bühler 1883, p. 59.

17. Charles Allen 2017, pp. 169–172.

18. Georg Bühler 1883, pp. 59–64.

19. Bhagavanlal Indraji (1878). Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Asiatic Society of Bombay. pp. 303–314.

20. D.C. Sircar 1965, p. 184.

21. Upinder Singh 2008, pp. 382–384

22. Charles Higham (2009). Encyclopedia of Ancient Asian Civilizations. Infobase Publishing. p. 299. ISBN 9781438109961.

23. Georg Bühler 1883, pp. 59-64 with footnotes.

24. Mirashi 1981, p. 231.

25. Mirashi 1981, pp. 232.

26. Report On The Elura Cave Temples And The Brahmanical And Jaina Caves In Western India by Burgess [1]

27. Singh, Upinder (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education India. pp. 436–438. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

28. Srinivasan, Doris (1979). "Early Vaiṣṇava Imagery: Caturvyūha and Variant Forms". Archives of Asian Art. 32: 50. ISSN 0066-6637. JSTOR 20111096.

29. Report On The Elura Cave Temples And The Brahmanical And Jaina Caves In Western India by Burgess [2]

30. Burgess, Jas (1883). Report on the Elura Cave temples and the Brahmanical and Jaina Caves in Western India.

31. Joanna Gottfried Williams (1981). Kalādarśana: American Studies in the Art of India. BRILL Academic. pp. 129–130. ISBN 90-04-06498-2.

32.Mirashi 1981, pp. 131–134.

33. Edwin F. Bryant (2007). Krishna: A Sourcebook. Oxford University Press. pp. 18 note 19. ISBN 978-0-19-972431-4.

34. Bhagvanlal Indraji (1876), On Ancient Nagari Numeration; from an Inscription at Naneghat, Journal of the Bombay Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, Vol. 12, pages 404-406

35. Anne Rooney (2012). The History of Mathematics. The Rosen Publishing Group. pp. 17–18. ISBN 978-1-4488-7369-2.

36. Stephen Chrisomalis (2010). Numerical Notation: A Comparative History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 189–190. ISBN 978-1-139-48533-3.

37. Vidya Dehejia (2008). The Body Adorned: Sacred and Profane in Indian Art. Columbia University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-231-51266-4.

38. Empires: Perspectives from Archaeology and History by Susan E. Alcock pp. 168–169, Cambridge University Press

Bibliography:

• Charles Allen (2017), "6", Coromandel: A Personal History of South India, Little Brown, ISBN 978-1408705391

• Georg Bühler (1883), Report on the Elura cave temples and the Brahmanical and Jaina caves in western India (Chapter: The Nanaghat Inscriptions), Archaeological Survey of India, This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

• Theo Damsteegt (1978). Epigraphical Hybrid Sanskrit. Brill Academic.

• Shobhana Gokhale (2004). "The Naneghat Inscription - A Masterpiece in Ancient Indian Records". The Adyar Library Bulletin. 68–70.

• Mirashi, Vasudev Vishnu (1981), History and Inscriptions of the Satavahanas: The Western Kshatrapas, Maharashtra State Board for Literature and Culture

• Norton, James H. K. (2001). Global Studies: India and South Asia. McGraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-243298-5.

• Richard Salomon (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

• Carla Sinopoli (2001). Susan E. Alcock (ed.). Empires: Perspectives from Archaeology and History. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-77020-0.

• Upinder Singh (2008). A History of Ancient and Early Medieval India: From the Stone Age to the 12th Century. Pearson Education. ISBN 978-81-317-1120-0.

• D.C. Sircar (1965), Select Inscriptions, Volume 1, University of Calcutta

• David E. Smith (1978). History of Mathematics. Courier. ISBN 978-0-486-20430-7.

Further reading:

• Alice Collet (2018). "Reimagining the Sātavāhana Queen Nāgaṇṇikā". Journal of the International Association of Buddhist Studies. 41: 329–358. doi:10.2143/JIABS.41.0.3285746.