Human Sacrifice (Purushamedha) Is Sanctioned In Hinduism [It's Not Just Symbolic] [Raja Sacrifice] [Suya-Sacrifice]

by Myth Buster

May 27, 2020

https://mythbusterx.wordpress.com/2020/ ... -hinduism/

Among the Lhota Naga, one of the many savage tribes who inhabit the deep rugged labyrinthine glens which wind into the mountains from the rich valley of Brahmapootra, it used to be a common custom to chop off the heads, hands, and feet of people they met with, and then to stick up the severed extremities in their fields to ensure a good crop of grain. They bore no ill-will whatever to the persons upon whom they operated in this unceremonious fashion. Once they flayed a boy alive, carved him in pieces, and distributed the flesh among all the villagers, who put it into their corn-bins to avert bad luck and ensure plentiful crops of grain. The Gonds of India, a Dravidian race, kidnapped Brahman boys, and kept them as victims to be sacrificed on various occasions. At sowing and reaping, after a triumphal procession, one of the lads was slain by being punctured with a poisoned arrow. His blood was then sprinkled over the ploughed field or the ripe crop, and his flesh was devoured. The Oraons or Uraons of Chota Nagpur worship a goddess called Anna Kuari, who can give good crops and make a man rich, but to induce her to do so it is necessary to offer human sacrifices. In spite of the vigilance of the British Government these sacrifices are said to be still secretly perpetrated. The victims are poor waifs and strays whose disappearance attracts no notice. April and May are the months when the catchpoles are out on the prowl. At that time strangers will not go about the country alone, and parents will not let their children enter the jungle or herd the cattle. When a catchpole has found a victim, he cuts his throat and carries away the upper part of the ring finger and the nose. The goddess takes up her abode in the house of any man who has offered her a sacrifice, and from that time his fields yield a double harvest. The form she assumes in the house is that of a small child. When the householder brings in his unhusked rice, he takes the goddess and rolls her over the heap to double its size. But she soon grows restless and can only be pacified with the blood of fresh human victims.

But the best known case of human sacrifices, systematically offered to ensure good crops, is supplied by the Khonds or Kandhs, another Dravidian race in Bengal. Our knowledge of them is derived from the accounts written by British officers who, about the middle of the nineteenth century, were engaged in putting them down. The sacrifices were offered to the Earth Goddess. Tari Pennu or Bera Pennu, and were believed to ensure good crops and immunity from all disease and accidents. In particular, they were considered necessary in the cultivation of turmeric, the Khonds arguing that the turmeric could not have a deep red colour without the shedding of blood. The victim or Meriah, as he was called, was acceptable to the goddess only if he had been purchased, or had been born a victim—that is, the son of a victim father, or had been devoted as a child by his father or guardian. Khonds in distress often sold their children for victims, “considering the beatification of their souls certain, and their death, for the benefit of mankind, the most honourable possible.” A man of the Panua tribe was once seen to load a Khond with curses, and finally to spit in his face, because the Khond had sold for a victim his own child, whom the Panua had wished to marry. A party of Khonds, who saw this, immediately pressed forward to comfort the seller of his child, saying, “Your child has died that all the world may live, and the Earth Goddess herself will wipe that spittle from your face.” The victims were often kept for years before they were sacrificed. Being regarded as consecrated beings, they were treated with extreme affection, mingled with deference, and were welcomed wherever they went. A Meriah youth, on attaining maturity, was generally given a wife, who was herself usually a Meriah or victim; and with her he received a portion of land and farm-stock. Their offspring were also victims. Human sacrifices were offered to the Earth Goddess by tribes, branches of tribes, or villages, both at periodical festivals and on extraordinary occasions. The periodical sacrifices were generally so arranged by tribes and divisions of tribes that each head of a family was enabled, at least once a year, to procure a shred of flesh for his fields, generally about the time when his chief crop was laid down.

The mode of performing these tribal sacrifices was as follows. Ten or twelve days before the sacrifice, the victim was devoted by cutting off his hair, which, until then, had been kept unshorn. Crowds of men and women assembled to witness the sacrifice; none might be excluded, since the sacrifice was declared to be for all mankind. It was preceded by several days of wild revelry and gross debauchery. On the day before the sacrifice the victim, dressed in a new garment, was led forth from the village in solemn procession, with music and dancing, to the Meriah grove, a clump of high forest trees standing a little way from the village and untouched by the axe. There they tied him to a post, which was sometimes placed between two plants of the sankissar shrub. He was then anointed with oil, ghee, and turmeric, and adorned with flowers; and “a species of reverence, which it is not easy to distinguish from adoration,” was paid to him throughout the day. A great struggle now arose to obtain the smallest relic from his person; a particle of the turmeric paste with which he was smeared, or a drop of his spittle, was esteemed of sovereign virtue, especially by the women. The crowd danced round the post to music, and addressing the earth, said, “O God, we offer this sacrifice to you; give us good crops, seasons, and health”; then speaking to the victim they said, “We bought you with a price, and did not seize you; now we sacrifice you according to custom, and no sin rests with us.”

On the last morning the orgies, which had been scarcely interrupted during the night, were resumed, and continued till noon, when they ceased, and the assembly proceeded to consummate the sacrifice. The victim was again anointed with oil, and each person touched the anointed part, and wiped the oil on his own head. In some places they took the victim in procession round the village, from door to door, where some plucked hair from his head, and others begged for a drop of his spittle, with which they anointed their heads. As the victim might not be bound nor make any show of resistance, the bones of his arms and, if necessary, his legs were broken; but often this precaution was rendered unnecessary by stupefying him with opium. The mode of putting him to death varied in different places. One of the commonest modes seems to have been strangulation, or squeezing to death. The branch of a green tree was cleft several feet down the middle; the victim’s neck (in other places, his chest) was inserted in the cleft, which the priest, aided by his assistants, strove with all his force to close. Then he wounded the victim slightly with his axe, whereupon the crowd rushed at the wretch and hewed the flesh from the bones, leaving the head and bowels untouched. Sometimes he was cut up alive. In Chinna Kimedy he was dragged along the fields, surrounded by the crowd, who, avoiding his head and intestines, hacked the flesh from his body with their knives till he died. Another very common mode of sacrifice in the same district was to fasten the victim to the proboscis of a wooden elephant, which revolved on a stout post, and, as it whirled round, the crowd cut the flesh from the victim while life remained. In some villages Major Campbell found as many as fourteen of these wooden elephants, which had been used at sacrifices. In one district the victim was put to death slowly by fire. A low stage was formed, sloping on either side like a roof; upon it they laid the victim, his limbs wound round with cords to confine his struggles. Fires were then lighted and hot brands applied, to make him roll up and down the slopes of the stage as long as possible; for the more tears he shed the more abundant would be the supply of rain. Next day the body was cut to pieces.

The flesh cut from the victim was instantly taken home by the persons who had been deputed by each village to bring it. To secure its rapid arrival, it was sometimes forwarded by relays of men, and conveyed with postal fleetness fifty or sixty miles. In each village all who stayed at home fasted rigidly until the flesh arrived. The bearer deposited it in the place of public assembly, where it was received by the priest and the heads of families. The priest divided it into two portions, one of which he offered to the Earth Goddess by burying it in a hole in the ground with his back turned, and without looking. Then each man added a little earth to bury it, and the priest poured water on the spot from a hill gourd. The other portion of flesh he divided into as many shares as there were heads of houses present. Each head of a house rolled his shred of flesh in leaves, and buried it in his favourite field, placing it in the earth behind his back without looking. In some places each man carried his portion of flesh to the stream which watered his fields, and there hung it on a pole. For three days thereafter no house was swept; and, in one district, strict silence was observed, no fire might be given out, no wood cut, and no strangers received. The remains of the human victim (namely, the head, bowels, and bones) were watched by strong parties the night after the sacrifice; and next morning they were burned, along with a whole sheep, on a funeral pile. The ashes were scattered over the fields, laid as paste over the houses and granaries, or mixed with the new corn to preserve it from insects. Sometimes, however, the head and bones were buried, not burnt. After the suppression of the human sacrifices, inferior victims were substituted in some places; for instance, in the capital of Chinna Kimedy a goat took the place of the human victim. Others sacrifice a buffalo. They tie it to a wooden post in a sacred grove, dance wildly round it with brandished knives, then, falling on the living animal, hack it to shreds and tatters in a few minutes, fighting and struggling with each other for every particle of flesh. As soon as a man has secured a piece he makes off with it at full speed to bury it in his fields, according to ancient custom, before the sun has set, and as some of them have far to go they must run very fast. All the women throw clods of earth at the rapidly retreating figures of the men, some of them taking very good aim. Soon the sacred grove, so lately a scene of tumult, is silent and deserted except for a few people who remain to guard all that is left of the buffalo, to wit, the head, the bones, and the stomach, which are burned with ceremony at the foot of the stake.

In these Khond sacrifices the Meriahs are represented by our authorities as victims offered to propitiate the Earth Goddess. But from the treatment of the victims both before and after death it appears that the custom cannot be explained as merely a propitiatory sacrifice. A part of the flesh certainly was offered to the Earth Goddess, but the rest was buried by each householder in his fields, and the ashes of the other parts of the body were scattered over the fields, laid as paste on the granaries, or mixed with the new corn. These latter customs imply that to the body of the Meriah there was ascribed a direct or intrinsic power of making the crops to grow, quite independent of the indirect efficacy which it might have as an offering to secure the good-will of the deity. In other words, the flesh and ashes of the victim were believed to be endowed with a magical or physical power of fertilising the land. The same intrinsic power was ascribed to the blood and tears of the Meriah, his blood causing the redness of the turmeric and his tears producing rain; for it can hardly be doubted that, originally at least, the tears were supposed to bring down the rain, not merely to prognosticate it. Similarly the custom of pouring water on the buried flesh of the Meriah was no doubt a rain-charm. Again, magical power as an attribute of the Meriah appears in the sovereign virtue believed to reside in anything that came from his person, as his hair or spittle. The ascription of such power to the Meriah indicates that he was much more than a mere man sacrificed to propitiate a deity. Once more, the extreme reverence paid him points to the same conclusion. Major Campbell speaks of the Meriah as “being regarded as something more than mortal,” and Major Macpherson says, “A species of reverence, which it is not easy to distinguish from adoration, is paid to him.” In short, the Meriah seems to have been regarded as divine. As such, he may originally have represented the Earth Goddess or, perhaps, a deity of vegetation; though in later times he came to be regarded rather as a victim offered to a deity than as himself an incarnate god. This later view of the Meriah as a victim rather than a divinity may perhaps have received undue emphasis from the European writers who have described the Khond religion. Habituated to the later idea of sacrifice as an offering made to a god for the purpose of conciliating his favour, European observers are apt to interpret all religious slaughter in this sense, and to suppose that wherever such slaughter takes place, there must necessarily be a deity to whom the carnage is believed by the slayers to be acceptable. Thus their preconceived ideas may unconsciously colour and warp their descriptions of savage rites.

-- The Golden Bough: A study of magic and religion, by Sir James George Frazer

Purushamedha literally translates into Human sacrifice where Purusha means Man and Medha means Sacrifice. The word Naramedha (Nara=Man; Medha=Sacrifice) is used in scriptures other than the Vedas. Human sacrifice is not currently practiced as it was banned since the British era. Although in the present age human sacrifices are rarely made, there can be no doubt of the existence of the practice formerly. But I am not talking about the prevalence of this practice although there have been some isolated incidents, I am talking about the scriptural sanctions of this practice. Unfortunately such evil practice has origins in Hindu scriptures. And hundreds or thousands of humans have fallen victim to this evil Hindu practice. There have been some isolated incidents of human sacrifice to Hindu goddess Kali in the present age.

It was only in 2014 that the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) started collecting data on human sacrifice. The statistics with the bureau reveal a disturbing picture: there were 51 cases of human sacrifice spread across 14 states between 2014 and 2016. https://www.thequint.com/news/india/god ... -sacrifice

India child killed in ‘human sacrifice’ ritual

http://www.bbc.com/news/world-asia-india-34409637

Four-year-old boy ‘beheaded in human sacrifice witchcraft ritual in India’

http://www.telegraph.co.uk/news/worldne ... India.html

Indian cult kills children for goddess

https://www.theguardian.com/world/2006/ ... heobserver

Indian father kills his eight-month-old son with an axe to appease Hindu goddess of destruction and rebirth

http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article ... birth.html

Five-year-old boy murdered as human sacrifice ritual in Andhra Pradesh; accused thrashed

http://indianexpress.com/article/india/ ... -thrashed/

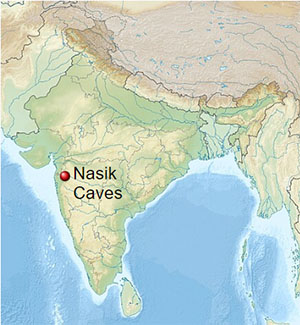

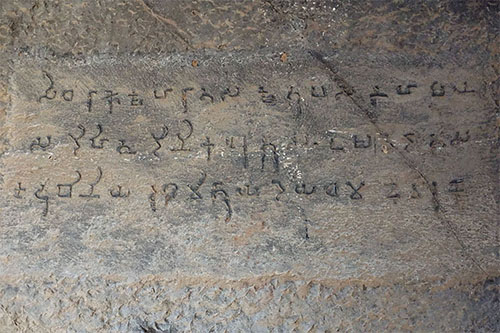

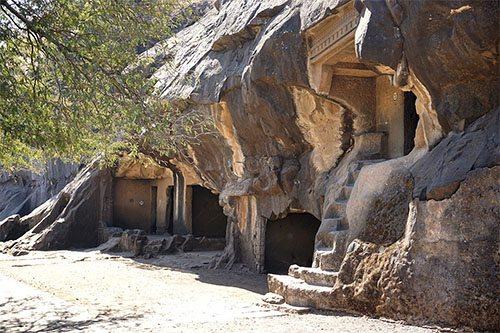

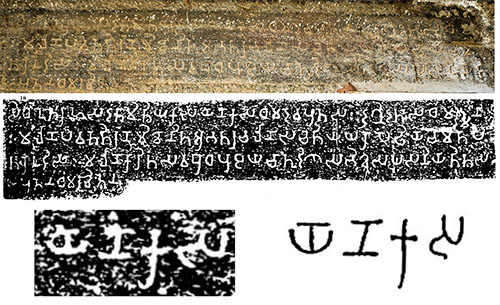

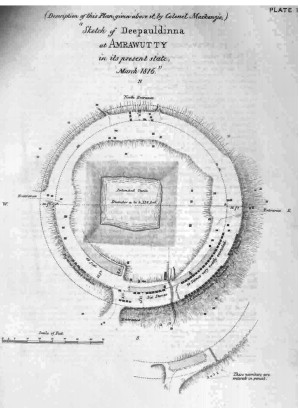

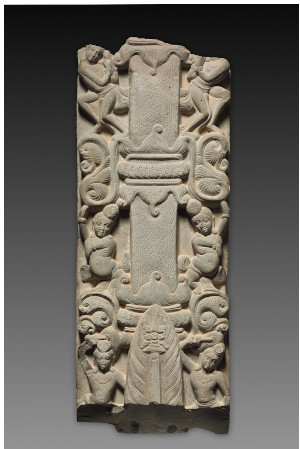

Archaeological evidence proves that human sacrifice was performed.

“‘Purushamedha Yagya’, sacrificing healthy and learned human male for political supremacy, was a tradition in the country. Concrete archaeological evidence of this kind of sacrifice has been found in Chhattisgarh’s neighbourhood.”

The report also shows that sometime a human model was symbolically sacrificed. That may have been done on the basis of Asvalayana Srauta Sutra which recommends symbolically sacrificing a human figure and tying a snake, the report shows that an iron snake was also found in the excavation. It may be a substitute for literal human slaughtering. And the archaeological findings also proves that horse were sacrificed in Ashvamedha Yajna, as remains of horse were found in the excavation,

“Pravarasena-I during his time had earlier performed Ashwamedha Yagya also. The remains were found at Mansar during manganese mining in 1935. The charred bone remains of the horse recovered were preserved in London museum.”

SOURCE: http://thehitavada.com/Encyc/2016/6/14/ ... edha-Yagya—Evidences-show-sacrifice-of-healthy,-scholarly-human-male-for-political-supremacy.aspx

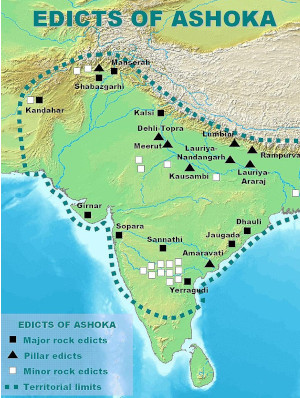

Archaeological evidence from Kausambi also proves slaughter of men in human sacrifice. Human bones and skull were found in an excavation at Kausabi,

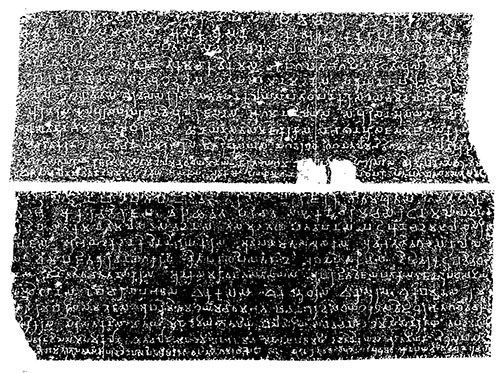

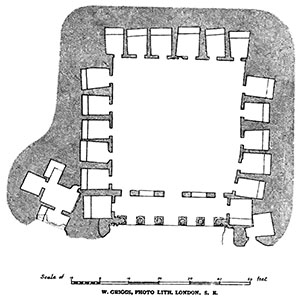

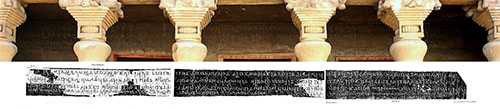

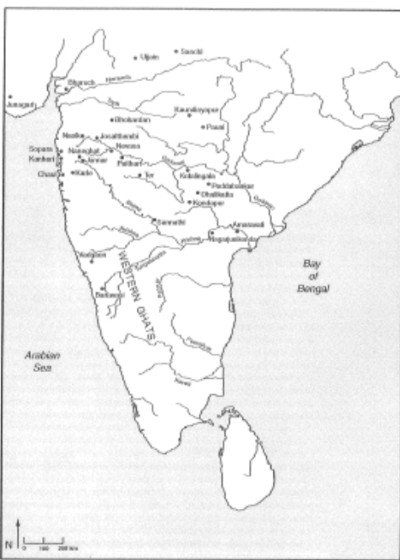

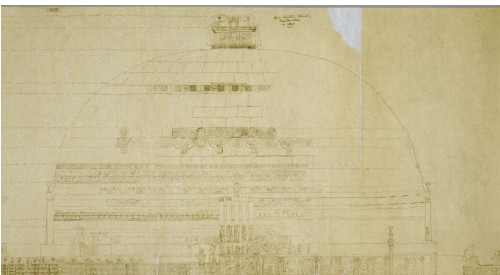

“The references to Kausambi in early literature and epigraphical records have been collated by N. N. Ghosh (1935), B. C. Law (1939) and G. R. Sharma (1969). The earlier history and archaeology of the city have been discussed in chapters 6, 7 and 10. Periods 3-5 of the fortification wall belong to the time-span of this chapter. Period 3 was dated by Sharma to the period of the Mitra kings of Kausambi who, on grounds of palaeography and other historical considerations, have been assigned to the period from the 2nd to the 1st century BC (Sharma 1960). Again, ‘on numismatic grounds’, Sharma states, ‘rampart 5 seems to have been built by the Maghas, who made Kausambi their capita) in the second half of the 2nd century AD’ (Sharma 1960). This numismatic argument has also been supplemented by the evidence of inscribed terracotta seals, terracotta figurines and iron arrowheads. The rampart wall rises even now to an average height of 1.5 m from the level of the surrounding plain, with its towers touching the 21-23 m level (Fig. 11.4). There were eleven gateways in all, of which five, two each on the cast and north and one on the west, have been considered to be the principal ones. The road leading to each gate was flanked by two mounds, obviously watchtowers, which lay across the moat encircling the rampart (except, of course, on the river side). About a mile away from this complex, there is another ring of mounds which once might have encircled the city. The rampart (of mud and bunt-brick revetment) was extended in the third stage and an interesting discovery was that of an altar outside the eastern gate at the foot of the rampart. This altar is supposedly shaped like an eagle flying to the southeast and associated with a fireplace, animal and human bones including a human skull. Sharma (1960, chapters 8-10) has adduced a mass of literary material to suggest that certain details of its construction correspond to the fire altar prescribed for purushamedha or human sacrifice in ancient Indian ritualistic texts.”

-- The Archaeology of Early Historic South Asia: The Emergence of Cities and States, p.298, By F. R. Allchin, George Erdosy, Cambridge University Press, 07-Sep-1995

Wendy Doniger also cites this in her book “On Hinduism”, although she mentioned this in various books but reference from one book will suffice,

“There is, however, in addition to the textual references to human sacrifice, also physical evidence of its performance, such as archaeological remains of human skulls and other human bones at the site of fire-altars, together with the bones of other animals, both wild and tame (horse, tortoise, pig, elephant, bovines, goats and buffalos).” On Hinduism, p.217, By Wendy Doniger, OUP USA, 2014

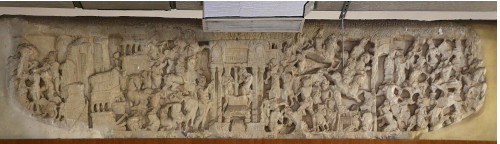

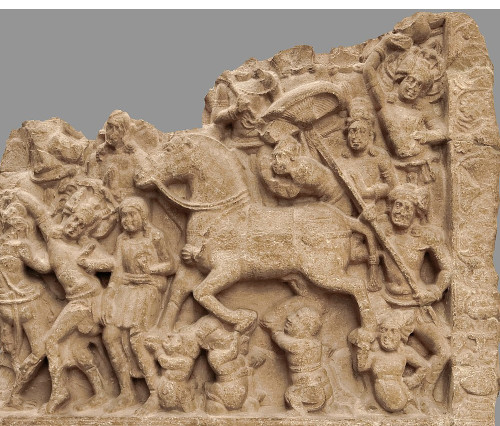

Purushamedha was performed to gain prestige, prosperity, power, atonement of sins, fulfil desires. The human victim was usually purchased from the family in lieu for a hundred or a thousand cows or horses. The man to be sacrificed was sometimes let loose before the sacrifice just like the horse in the horse sacrifice. While he was let loose, all his desires were fulfilled except for carnal desires. The human victim was tied to a pillar or pole then anointed with oil or other things and then he was either slaughtered or immolated in human sacrifice, human victim was also suffocated. As per Apastamba Srauta Sutra 20.24.2 this ceremony is to be performed only by a Brahmin or a Kshatriya. Killing of a Brahmin is called Brahmin-slaughter in Hindu scriptures and it’s the major sin but in the Purushamedha the human victim can be a Brahmin also. Sankhayana Srautasutra 16.10.2 mentions that the victim can be a Brahmin or a Kshatriya also. Hindu scriptures also describes how the physical traits of the human victim should be, the human victim should be fit, not crippled, not black in complexion etc. Taittriya Brahmana 3rd Kanda, Fourth Prapathaka, chapters 1-16 and Chapter 30 of Vajasaneyi Samhita (Yajurved) mentions the list of human victims that should be sacrificed while some scholars says that Purushamedha mentioned in Taittriyia Brahmana is symbolical (because it’s a elaboration of Yajur Veda) and the victim is set free after the symbolic sacrifice. Some of the victims includes paramour, flute blower, drum beater, maker of ointment, gatherer of wood, astrologer, fisherman etc. The Kathyayana Srautasutra 16.1.14 adds that the man is to be slain in a screened shed. What is done with the flesh of the sacrificed man is not clear, the flesh of animals sacrificed in Ashvamedha and other sacrifices is to be eaten by priests and Sacrificers but that doesn’t seem to be the case with Purushamedha as consumption of human flesh is prohibited for Hindus. Kings used to offer their rival kings in human sacrifice, there is a reference of Jarasandha going to slaughter his rival kings in Purushamedha wherein he was stopped from doing so by Krishna, but Krishna didn’t prohibit Purushamedha there. He refused that such practice exists, he clearly denied the existence of such practice, which is mentioned in Mahabharata. A Srauta Sutra commands to offer rival kings if no one comes forward to be offered as human victim. Human sacrifice may have not been performed by Vaishnavite Hindus, Human sacrifice may have been practiced mainly by the Shaivite Hindus as it’s evident from Shaivite Puranas which gives instructions on how to perform human sacrifice and most of the verses about human sacrifice are related to Shaivites.

According to Sankhayana Srautasutra 16.12.21-16.13.1-9, the man who has been chosen as the chief victim is killed (by suffocating), and ‘when he is quieted (i.e., killed), the Udgatar sings over him, standing near him, the Saman which is addressed to Yama (the god of death),’ and ‘the Hotar recites over him the Purusa-Narayana-hymn.’ Then, ‘When the man has been quieted, they cause the first consort of the Sacrificer to lie down near him,’ and ‘the Sacrificer addresses these two in the same manner (as in the horse sacrifice).’

According to Julius Eggeling the Purushamedha mentioned in Sankhayana and Vaitana is a modern adaption intended to fill the gap between sacrificial system which seemed to require a man but this doesn’t convince me. I am reproducing verses from Sankhayana and Vaitana Srauta Sutras which gives details on how Purushamedha is performed.

Sankhayana Srauta Sutra XVI, 10, 1 “Pragâpati, having offered the Asvamedha, beheld the Purushamedha: what he had not gained by the Asvamedha, all that he gained by the Purushamedha; and so does the sacrificer now, in performing the Purushamedha, gain thereby all that he had not gained by the Asvamedha. 2, 3. The whole of the Asvamedha ceremonial (is here performed); and an addition thereto. 4-8, First oblations to Agni Kama (desire), A. Dâtri (the giver), and A. Pathikrit (the path-maker). 9. Having bought a Brâhmana or a Kshatriya for a thousand (cows) and a hundred horses, he sets him free for a year to do as he pleases in everything except breaches of chastity. 10. And they guard him accordingly. 11. For a year there are (daily) oblations to Anumati (approval), Pathyâ Svasti (success on the way), and Aditi. 12. Those (three daily oblations) to Savitri in the reverse order. 13. By way of revolving legends (the Hotri recites) Nârasamsâni . . .–XVI, II, 1-33 enumerate the Nârasamsâni, together with the respective Vedic passages.–XVI, 12, 1-7. There are twenty-five stakes, each twenty-five cubits long . . .; and twenty-five Agnîshomîya victims. 8. Of the (three) Asvamedha days the first and last (are here performed). 9-11. The second (day) is a pañkavimsa-stoma one . . . 12. The Man, a Gomriga [a kind of ox], and a hornless (polled) he-goat–these are the Prâgâpatya (victims). 13. A Bos Gaurus, a Gayal, an elk (sarabha), a camel, and a Mâyu Kimpurusha (? shrieking monkey) are the anustaranâh. 14-16. And the (other) victims in groups of twenty-five for the twenty-five seasonal deities . . . 17. Having made the adorned Man smell (kiss) the chanting-ground, (he addresses him) with the eleven verses (Rig-v. X, 15, 1-11) without ‘om,’–‘Up shall rise (the Fathers worthy of Soma), the lower, the higher, and the middle ones.’ 18. The Âprî verses are ‘Agnir mrityuh‘ . . . 20. They then spread a red cloth, woven of kusa grass, for the Man to lie upon. 21. The Udgâtri approaches the suffocated Man with (the chant of) a Sâman to Yama (the god of death).–XVI, 13, 1. The Hotri with (the recitation of) the Purusha Nârâyana (litany). 2. Then the officiating priests–Hotri, Brahman, Udgâtri, Adhvaryu–approach him each with two verses of the hymn (on Yama and the Fathers) Rig-v. X, 14, ‘Revere thou with offering King Yama Vaivasvata, the gatherer of men, who hath walked over the wide distances tracing out the path for many.’ 3-6. They then heal the Sacrificer (by reciting hymns X, 137; 161; 163; 186; 59; VII, 35). 7-18. Ceremonies analogous to those of the Asvamedha (cf. XIII, 5, 2, 1 seqq.), concluding with the Brahmavadya (brahmodya).–XVI, 14, 1-20. Details about chants, &c.; the fourth (and last) day of the Purushamedha to be performed like the fifth of the Prishthya-shadaha.” Tr. Julius Eggeling

Following two passages from Sankhayana Srauta Sutra also promotes necrophilia.

Sankhayana Srauta Sutra XVI.12.6-21 “There are twenty five victims to be immolated to Agni and Soma…Purusa (man), forsooth, consists of twenty five parts (or it is the twenty fifth). Thereby he makes him thrive by his own characteristic. The victims to be immolated to Prajapati are a man, a gomriga and a hornless he goat…The human victim, which has been adorned, they make smell the spot where the out of doors land is performed and (they praise it) with the eleven (verses) not joining the pranava ‘Let the nearer ones arise.’ The apri verses are “Agni, death” The hymn ‘Do not burn him’ he should insert in the adhrign formula in the same manner as (at the asvamedha). Now they spread out for the human victim a garment of kusa grass, a (cloth) of trpa bark, a red garment of silk threads. When it is ‘quieted’ the udgatr sings over it standing near it the saman addressed to Yama.” Tr. W. Caland

Sankhayana Srauta Sutra XVI.13.1-8 “And the hotr recites over it the purusa narayana (hymn). Now the principal priests hotr, brahman, udgatr and adhvaryu address to it each two of the verses of the hymn Him who has gone hence… When the human victim has been quieted, they cause the first consort of the sacrificer (king) to lie down near it. They cover them both with the upper garment.” Tr. W. Caland

The Vaitana Srauta Sutra talks about purchasing a man for a thousand cows and if no one comes forward then he should conquer his nearest enemy and sacrifice him.

Vaitana Srauta Sutra XXXVII, 10. The Purushamedha (is performed) like the Asvamedha

. . . 12. There are offerings to Agni Kama, Dâtri, and Pathikrit. 13. He causes to be publicly proclaimed, ‘Let all that is subject to the Sacrificer assemble together!’ 14. The Sacrificer says, ‘To whom shall I give a thousand (cows) and a hundred horses to be the property of his relatives? Through whom shall I gain my object?’ 15. If a Brâhmana or a Kshatriya comes forward, they say, ‘The transaction is completed.’ 16. If no one comes forward, let him conquer his nearest enemy, and perform the sacrifice with him. 17. To that (chosen man) he shall give that (price) for his relatives. 18. Let him make it he publicly known that, if any one’s wife were to speak, he will seize that man’s whole property, and kill herself, if she be not a Brâhmana woman. 19. When, after being bathed and adorned, he (the man) is set free, he (the priest) recites the hymns A.V. XIX, 6; X, 2.-20. For a year (daily) offerings to Pathyâ Svasti, Aditi, and Anumati. 21. At the end of the year an animal offering to Indra-Pûshan. 22. The third day is a Mahâvrata. 23. When (the man) is bound to the post, he repeats the three verses, ‘Up shall rise’ . . .; and when he is unloosened, the utthâpanî-verses. 24-26. When he is taken to the slaughtering-place (the priest repeats) the harinî-verses; when he is made to lie down, the two verses, ‘Be thou soft for him, O Earth’; and when he has been suffocated, (he repeats) the Sahasrabâhu (or Purusha Nârâyana) litany, and hymns to Yama and Sarasvatî–XXXVIII, 1-9 treat of the subsequent ceremonies, including the recitation, by the Brahman, of hymns with the view of healing the Sacrificer.

Verses from Devi Bhagavatam shows that human was immolated in Purushamedha. It’s about Shunashepa,

Devi Bhagavatam 7.15.8-10. O Deva of the Devas! I will obey your order no doubt and I will perform your sacrifice according to the Vedic rites and with profuse Daksinâs (remuneration to priests, etc.) But, when in a sacrifice human beings are immolated as victims, both the husband and wife are entitled to the ceremony…” Tr. Swami Vijnananda