by Prasun Sonwalkar

Journalism Studies, Vol. 16, No. 5, 624–636

2015

NOTICE: THIS WORK MAY BE PROTECTED BY COPYRIGHT

YOU ARE REQUIRED TO READ THE COPYRIGHT NOTICE AT THIS LINK BEFORE YOU READ THE FOLLOWING WORK, THAT IS AVAILABLE SOLELY FOR PRIVATE STUDY, SCHOLARSHIP OR RESEARCH PURSUANT TO 17 U.S.C. SECTION 107 AND 108. IN THE EVENT THAT THE LIBRARY DETERMINES THAT UNLAWFUL COPYING OF THIS WORK HAS OCCURRED, THE LIBRARY HAS THE RIGHT TO BLOCK THE I.P. ADDRESS AT WHICH THE UNLAWFUL COPYING APPEARED TO HAVE OCCURRED. THANK YOU FOR RESPECTING THE RIGHTS OF COPYRIGHT OWNERS.

-- The Printing Press in India: Its Beginnings and Early Development, Being a Quartercentenary Commemoratino Study of the Advent of Printing in India (in 1556), by Anant Kakba Priolkar, With a Foreword by Shri Chintaman D. Deshmukh, and An Historical Essay on the Konkani Language, by J.H. Da Cunha Rivara, 1958

-- Calcutta School-Book Society, by Wikipedia

-- Krista Purana, by Wikipedia

-- Journal of the Buddhist Text Society of India, Volume 4, edited by Sarat Chandra Das, C.I.E.

India’s imperfect democracy may be underpinned by an equally imperfect journalism, but the symbiotic relationship between the two is rarely acknowledged or highlighted. The fact remains that India’s democracy is enabled and enhanced by its roots in the ancient tradition of dialogue, debate and argument, which was transformed by the growth of print journalism since the late eighteenth century. In the modern sense, this tradition matured in the acid bath of India’s freedom struggle, when journalism and journalist-leaders such as Gandhi and Nehru played a central role before independence in 1947. This paper focuses on a forgotten chapter in India’s modern political history, when the idea of a free press became the locus of the earliest example of constitutional agitation. In the colonial cauldron of the early nineteenth century, protest by Indian and British liberals against press licensing and other restrictions imposed by the East India Company took the form of “memorials” (petitions) addressed to the Supreme Court in Calcutta1 and to the King-in-Council in London. The agitation begun in Calcutta in 1823 was carried forward in London, which later curbed the Company-state’s restrictive acts towards the press in India, until the Mutiny of 1857. The agitation also included the daring act of Rammohun Roy to close his Persian journal, Mirat-ul-Akhbar, to protest against restrictions imposed by acting Governor-General John Adam. Recalling this chapter of political protest enhances our understanding of the dominant theme of politics in Indian journalism, which continues today, despite rampant commercialisation and corruption.

KEYWORDS East India Company; freedom of the press; memorials; press; press ordinance; protest

Introduction

The 2014 general elections in India—considered the largest democratic exercise in the world—provide a convenient backdrop to explore the symbiotic and deep relationship between politics and journalism in India. Superlatives are often used to describe various aspects about India, from its 1.2 billion plus population, to levels of poverty, to the growing number of millionaires and billionaires. Superlatives are also used to describe the ways in which the Indian news media covered—or did not cover—the 2014 elections. In the context of deepening of the corporate–politician nexus since the liberalisation of India’s economy in the early 1990s, there are indications that the 2014 elections witnessed unprecedented levels of commerce and compromise on the part of the news media. Large numbers of candidates, constituencies, parties and issues were systematically marginalised in news discourse in favour of certain politicians and their parties. American-style branding of candidates and parties was taken to new highs of manufacturing consent as thousands of techno-savvy volunteers lent their expertise (including holograms) to selectively influence the discourse. Manoj Ladwa, who was the head of public relations of Bharatiya Janata Party’s campaign, said after the party’s landslide electoral victory: “We studied the Barack Obama and Tony Blair campaigns, but this was a [Narendra] Modi campaign and it will be seen as a benchmark in political communication on media courses” (Sonwalkar 2014, 11).

The news coverage of the elections presents itself as a rare case study of professionalisation of political communication and western-style methods being deployed in a traditional society that is undergoing transformation at various levels, but continues to face serious challenges of poverty, health, education and security. If the news coverage of the 2014 elections is seen as plunging new depths of corruption, misuse and manipulation— partly captured in the phrase “paid news”, which means politicians paying for propaganda masquerading as news content—it also reflects and reiterates a reality that is so banal and boring that it is rarely acknowledged or noticed. It is the reality of politics being the default setting of Indian journalism, an aspect that defies Murdoch-style dumbing down of news content for commercial gains. Since the early 1990s, news content has become light as part of the “Murdochization” of Indian journalism (Sonwalkar 2002), with increasing focus on celebrities, cinema, crime and cricket, but the historical hard-wiring of politics in Indian society, as reflected in journalism, has retained its salience. Political events and issues are often narrated in Bollywood-style imagery and idioms, particularly on television, but despite the rapacious pursuit of profit and corruption by news organisations and some journalists, the dominance of politics, party leaders and issues has continued across the news media, including print, radio, television and the rapidly expanding social media. This article focuses on this core, umbilical link between journalism and politics in India, and recalls the first—but largely forgotten—chapter of protest in the early nineteenth century that set the template for subsequent political agitations, culminating in India’s independence in 1947.

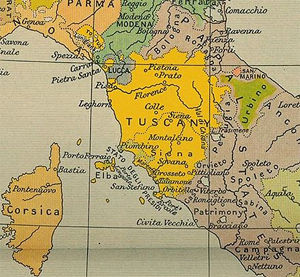

The origin of modern journalism in India in the late eighteenth century presents a unique case study of the idea of “British journalism abroad”, of how the ways of doing journalism travelled from England to various colonies of the British Empire, how the “model” was received, adopted and constructively adapted by the local elites, and how journalism of this period prepared the groundwork for the use of the press as a powerful weapon during freedom struggles, particularly in non-Dominion or non-Settler colonies such as India. According to standard historical accounts, Indian nationalism began in 1885 with the formation of the Indian National Congress, or during the preparatory phase of agitational politics in the preceding decade. However, the vast material comprising hand-written records of the East India Company (EIC) and surviving copies of the first English and Indian-language journals suggest that by as early as 1835, print journalism had emerged as a site where the first impulses of Indian nationalism were being expressed. Journalism had also become an effective tool for social and religious reform. It had become a key aspect of what was then a new form of political protest—constitutional agitation—which included petitions to EIC officials, town hall meetings in Calcutta, seeking legal alternatives and raising issues through the press. Later, Mahatma Gandhi, Jawaharlal Nehru and other leaders of India’s freedom struggle followed the example set by the the first leader-journalists such as Rammohun Roy, H. L. V. Derozio and Bhabani Charan Bandopadhyay, and used journalism to powerful effect. By 1835, Indians were already using print journalism to lecture to the British on how to run their empire, and writing extensively about the Irish and the revolutionary struggles in Spain and Italy as part of veiled attacks on the company’s rule in India. This focus on politics in the early phase of Indian journalism helps partly explain the persistence of politics as the dominant theme in modern India’s news media.

The next section places the origins of modern journalism in India in historical context and summarises key developments until the early nineteenth century. Journalism itself became the focus of the first political struggle in the colonial cauldron at the time, as top officials of the EIC saw the press as a threat and imposed severe restrictions. Matters came to a head in 1823, when acting Governor-General John Adam took two steps: deporting the irrepressible editor John Silk Buckingham, whose Calcutta Journal often launched scathing attacks on the Company government and its leading individuals; and issuing a Press Ordinance that imposed severe restrictions on the press. It is the response to this Press Ordinance by leading Indians in Calcutta that provides a remarkable and first example of modern ideas and the press being used in political protests in colonial India. As Gaonkar (1999, 17) observed, “Modernity is more often perceived as a lure than as threat, and the people (not just the elite) everywhere, at every national or cultural site, rise to meet it, negotiate it, and appropriate it in their own fashion”. The Indian response to the Press Ordinance took the form of two memorials (petitions)—one addressed to the Supreme Court in Calcutta and the other to the King-in-Council (so-called when the sovereign is acting on the advice of the Council); and in an act described as “daring” at the time, social reformer Rammohun Roy closed his Persian journal, Mirat-ul-Akhbar, in protest. As historian R. C. Dutt put it, “It was the start of that system of constitutional agitation for political rights which their countrymen have learnt to value so much in the present day” (Majumdar 1965, 234). The response also included transnational protest when Buckingham, deported to England, continued his diatribe in print against the Company government from London. This article, however, focuses on the Indian response: the two memorials and the closure of Roy’s journal.

The Context of Early Indian Journalism

This period in Indian journalism history was marked by political flux, when the Mughal Empire was in decline and a commercial enterprise from England—the East India Company—was coming to terms with the reality of having assumed political power over most of the sub-continent. It was a period of much uncertainty, when nothing was a given. In mid-eighteenth century Mughal India, slowly but surely, the old was giving way to the new in complex ways. The Mughal Empire was losing its influence, while the EIC gained political power and influence after the Battle of Plassey (1757), Battle of Buxar (1764) and the Treaty of Allahabad (1765), in which the Mughal Emperor formally acknowledged British dominance in the region by granting EIC the diwani, or the right to collect revenue, from Bengal, Bihar and Orissa. The Supreme Court was founded in Calcutta in 1774. The EIC ceased to be simply a trading company and transformed into a powerful imperial agency with an army of its own, exercising control over vast territories with millions of people. As Thomas B. Macaulay said during a speech in the House of Commons on 10 July 1833: “It is the strangest of all governments; but it is designed for the strangest of all empires”. Elsewhere, the close of the eighteenth century was a period of cataclysmic change: American and French Revolutions had a profound influence not only on rulers in England but also on officials of the EIC. Radical politics began to emerge in England from the 1750s, which was strongly resisted by the forces of status quo. The same fears gripped the early officers of the expansionist EIC as it established itself in Calcutta and spread its influence across India.

Journalism emerged amidst such conditions and uncertain attempts by the Company government to introduce new, modern ways of governance and other measures, most of which proved controversial and faced opposition from Indians. The Company government, at the time engaged in battles across India, watched uneasily as English-language journals were launched from 1780 onwards, when James Augustus Hicky published the first journal, Hicky’s Gazette Or Calcutta General Advertiser. Alert to the dangers of Jacobinism [supporters of a centralized republican state and strong central government powers and/or supporters of extensive government intervention to transform society], the EIC tried to control the press and prevent its growth from as early as 1799, by when British entrepreneurs and agency house came together to launch more journals. The question of freedom of the press first exercised colonial authorities at the time of Richard Wellesley’s governorship (1798–1805), when the Company government interpreted any criticism in journals as lurking Jacobinism. In 1799, Wellesley introduced regulations for the press, which stipulated that no newspaper be published until the proofs of the whole paper, including advertisements, were submitted to the colonial government and approved; violation invited deportation to England. Until 1818, the regulations applied only to the English journals, because until that year, there were no journals in Indian languages.

The Company government succeeded in controlling the press until 1818, by when the combination of a proliferating commercially driven print culture, a growing British community, a new generation of British editors and administrators, Christian missionaries and Indian elites alert to new ideas and impulses, ensured the growth of journalism and the idea of a free press. Several English-language journals followed Hicky’s journal, as members of the small British community in Calcutta sought to recreate the British world and cultural conditions in England: “[As] the German demands his national beverages wherever he settles, so the Briton insists on his newspaper” (Mills 1924, 103). Calcutta became the setting for the origins of Indian journalism and the crucible of the first sustained cultural encounter between Indian intellectuals and the west. In the late eighteenth century (1780), the white population in the town was less than 1000; in the 1837 census, 3138 English were returned, with soldiers forming the main element of the community. A part of Calcutta came to be known as the “white town”, where the British based themselves and sought to recreate British cultural life through news, goods, music, theatre and personnel that arrived and left for England by sea. As Marshall (2000, 308–309) noted, the “vast majority of the British were not interested in any exchange of ideas with the Indians. They did not expect to give anything, still less to receive. They were solely concerned with sustaining British cultural life for themselves with as few concessions as possible to an alien environment”.

Yet, members of the Indian intelligentsia, such as Rammohun Roy, living in Calcutta responded in creative ways to aspects of European culture that became available to them. Some members of the British community, on their own, developed cultural contacts with the local population, notably Sir William Jones, Nathaniel Halhed, Charles Wilkins and, for evangelical reasons, the Baptist missionaries in nearby Serampore. Indian scholars employed at the Fort William College also brought them in close contact with the British. As EIC’s presence spread and grew in its influence, Calcutta became the centre of governance, attracting unofficial Britons seeking to make a fortune, thus setting the scene for discursive interactions with the local population at various levels, including in the field of journalism (such as it was then). Indian intellectuals such as Roy were quick to absorb new ideas from the west. At the time, as Raichaudhuri (1988, 3) noted, “The excitement over the literature, history and philosophy of Europe as well as the less familiar scientific knowledge was deep and abiding”.

At the heart of this “excitement” was the technology of print, which enabled the flow of ideas and news from the metropole to the colonial periphery, vice versa, and slowly beyond Calcutta to the other two presidencies of Madras and Bombay and elsewhere. The printing press first arrived in India in Goa with Portuguese missionaries in the mid-sixteenth century. Several religious texts were later printed in Konkani, Tamil and other Indian languages, but it was not until the late eighteenth century that the first English-language journals were launched in Calcutta, followed by journals in Bengali, Persian and Hindi in Calcutta, and in other Indian languages in Madras and Bombay. In the last two decades of the eighteenth century, “Calcutta rapidly developed into the largest centre of printing in the sub-continent … appropriate to its paramount importance to the British as an administrative, commercial and social base” (Shaw 1981, ix).

Hicky catered to the small but expanding British community, which was able to sustain more English journals, some of them launched with the support of the EIC. As Marshall (2000, 324) noted, “White Calcutta sustained a remarkable number of newspapers and journals in English. Between 1780 and 1800, 24 weekly or monthly magazines came into existence … The total circulation of English-language publications was put at 3000 … These are astonishing figures for so small a community”. It was the era of journalist as publicist, as editors—in England and in colonial India—stamped their personalities on their journals, often entering into vicious attacks against rival editors and officials of the EIC. Hicky bitterly attacked Governor-General Warren Hastings, chief justice of the Supreme Court Sir Elijah Impey and others in the British community in Calcutta. The English journals were mainly non-political in character, sustained by advertising and had the British community as its audience. Besides some criticism of the EIC by mostly anonymous letter writers to the editor, the journals published orders of the colonial government, Indian news, personal news, notes on fashion, extracts from papers published in England, parliamentary reports, poems, newsletters and reports from parts of Europe. Editorials and other content would mainly interest the British community.

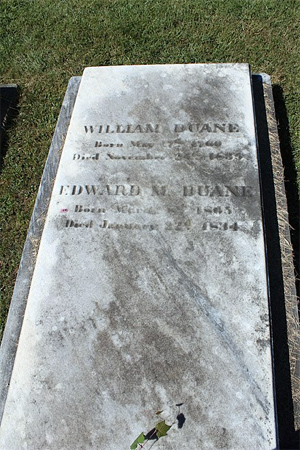

If Hicky’s journal is better known historically for publication of scandals, scurrilous personal attacks and risqué advertisements selling sex and sin, he was also the first to fight against the colonial government, then almost single-handed, to defend the liberty of the press. He wrote: “Mr Hicky considers the Liberty of the Press to be essential to the very existence of an Englishman and a free G-t. The subject should have full liberty to declare his principles, and opinions, and every act which tends to coerce that liberty is tyrannical and injurious to the COMMUNITY” (Barns 1940, 49, italics and capitals in original; in the days of letter press, “G-t” stood for “Government”). Hicky was soon hounded by Hastings and Impey, fined, imprisoned and his journal closed in March 1782. He died in penury in 1802. He was the first of several editors of English journals to invite the wrath of EIC officials who were wary of the effects of the ideas spawned by the French Revolution in India, and were highly sensitised to any threats to the existing order. By 1800, some journals closed for want of advertising and subscription, while others closed when British editors were deported to England after publishing material that was considered unacceptable by the EIC. Editors who attracted EIC’s ire and found themselves on ships back to England included William Duane, editor of Bengal Journal, removed as editor and almost deported in 1791, and finally deported as editor of Indian World in 1794; Charles Maclean, editor of Bengal Hurkaru, deported in 1798; James Silk Buckingham, editor of Calcutta Journal, and his assistant, Sandford Arnot, deported in 1823; and C. J. Fair, editor of Bombay Gazette, also deported in 1823.

The year 1818 had witnessed developments that catalysed the growth of journalism in an expanding colonial India. As noted above, deportation remained a key instrument to discipline British editors, but the measure could not be applied to editors who were Indians or to Europeans born in India. To remove the anomaly, the Marquess of Hastings, who was governor-general from 1813 to 1823, removed the 1799 censorship and issued a new set of rules in 1818. In a circular to all editors and publishers in Calcutta, he set out guidelines with a view to prevent the publication of topics considered dangerous or objectionable, or face deportation. But his new rules did not possess the force of law as they were not passed into a Regulation in a legal manner, which meant that in practice there were no legal restrictions on the press. The Marquess of Hastings was soon hailed in Calcutta as a liberator of the press. In the same year, the first journals in an Indian language— Bengali—were launched, the precursors of several Indian-language journals in other parts of India. There is a dispute about which was published first, the Bengal Gejeti edited by Harachandra Roy with the assistance of Gangakishore Bhattacharya, or Samachar Darpan, launched by the Baptist missionaries at Serampore—both were launched in May 1818 (some scholars claim that Bangal Gejeti was launched in 1816). The missionaries had earlier launched the monthly Digdarsan in April 1818, but due to the missionary context, nationalist historians credit Bangal Gejeti as the first journal in an Indian language, but it did not last for more than a year (none of its issues are known to exist). The year 1818 also saw the launch of Buckingham’s Calcutta Journal, on 2 October, a biweekly of eight quarto pages, which was to come into frequent conflict with EIC and also encourage the growth of the indigenous press by often publishing extracts from the Indian-language journals and commenting favourably on their growth. A Whig, Buckingham propagated liberal ideas and views through his journal that almost reached the record daily circulation figure of 1000 copies. As the editor, he wrote, he conceived his duty to be “to admonish Governors of their duties, to warn them furiously of their faults, and to tell disagreeable truths” (Barns 1940, 95). Setting himself up as a champion of free press, Buckingham saw a free press as an important check against misgovernment, especially in Bengal, where there was no legislature to curb executive authority.

By the beginning of the nineteenth century, a “multifarious culture of the print medium” had come into existence in India:

It was the first fully formed print culture to appear outside Europe and North America and it was distinguished by its size, productivity, and multilingual and multinational constitution, as well as its large array of Asian languages and its inclusion of numerous non-Western investors and producers among its participants. (Dharwadker 1997, 112)

Print journalism had found a fertile soil in colonial Calcutta, but it also generated near-panic among colonial officials about its potential subversive effect on the army. Expressing “intense anxiety and alarm”, Chief Secretary John Adam (1822) wrote in a lengthy minute on the press: “That the seeds of infinite mischief have already been sown is my firm belief”. When the Marquess of Hastings sailed for England on 9 January 1823, he was temporarily succeeded as governor-general by John Adam, whose first act was to deport Buckingham to England, which led to the closure of Calcutta Journal. Secondly, Adam promulgated a rigorous Press Ordinance on 14 March 1823, which made it mandatory for editors and publishers to secure licences for their journals. To secure the licences, they had to submit an affidavit to the chief secretary under oath. For any offence of discussing any of the subjects prohibited by law, the editor or publisher was liable to lose the licence.

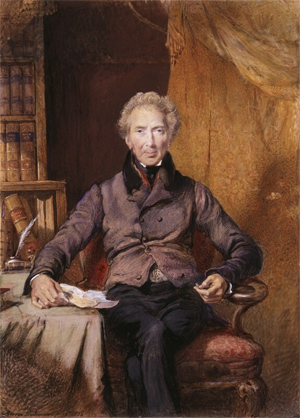

The following sections set out the Indian response to the Press Ordinance, mainly directed by Rammohun Roy (1772–1833), who is less known for his contribution to Indian journalism than for his reformist initiatives in the realm of religion, education and social awareness (in particular, for his campaign to abolish sati or widow burning). Considered in hagiographic and nationalistic accounts as the founder of modern India, most of his reformist initiatives were conducted through the technology of print in the form of pamphlets, translations, tracts and journals. He was closely associated with at least five journals: Bengal Gejeti (Bengali, 1818), The Brahmunical Magazine (English–Bengali, 1821), Sambad Kaumidi (Bengali, 1821), Mirat-ul-Akhbar (Persian, 1822) and Bengal Herald (English, 1829). Roy—easily one of the foremost examples of an “argumentative Indian” (Sen 2005)— often engaged in lengthy debates with Baptist missionaries and used his polemical skills to oppose the Press Ordinance.

Press Ordinance and Two Memorials

Before the Press Ordinance was issued on 14 March 1823, officials in the governor-general’s administration were clamouring for legal restrictions on what they saw as “excesses” of the press. In a lengthy minute dated 14 August 1822, John Adam (1822) wrote: “My objection is to the claim of that class of persons to exercise in this country, the privileges they are allowed to assume at home, of sitting in judgement on the acts of Government, and bringing public measures and the conduct of public men, as well as the concerns of private individuals, before the bar of what they miscall public opinion”. Another senior official, W. B. Bayley, wrote on 10 October 1822: “Feeling as I do that the Native Press may be converted into an engine of the most serious mischief, I shall … state the grounds on which I consider it essential that the Government should be vested with legal power to control the excesses of the Native as well as the European Press”.

The Marquess of Hastings, who had tolerated much criticism from Buckingham and had refrained from taking action, was faced with an increasingly belligerent group of officials, who wanted more powers to clamp down on the press. The Marquess of Hastings finally wrote to London in October 1822 for more such powers, but before any progress could be made on the issue, he returned to England on 9 January 1823. Adam, the senior-most official at the time, took over as the acting governor-general, and as stated above, his first two acts in office were deporting Buckingham to London, and issuing the rigorous Press Ordinance. Under the laws of the time, every new executive measure had to be submitted to the Supreme Court for registration before it could come into force. Adam’s Press Ordinance was submitted to the court on 15 March 1823, and two days later, Rammohun Roy and four others submitted a memorial, asking the court to hear objections against it. Besides Roy, it was signed by three Tagores (Chunder Coomar, Dwarkanath, Prosunno Coomar), Hurchunder Ghosh and Gowree Churn Bonnergee.

The memorial discussed in a logical manner the general principles on which the claim of freedom of the press was based in all modern countries, and recalled the contribution Indians had made to the growth of British rule. It created a sensation at the time and came to be described as the “Aeropagitica of Indian history” (Collet 1988, 180, italics in original). The memorial pointed out the aversion of Hindus to undertaking an oath because of “invincible prejudice against making a voluntary affidavit, or undergoing the solemnities of an oath”. Using the rhetorical strategy of professing loyalty and attachment of the Indians to British rule, the memorialists wrote that they were “extremely sorry” to note that the new restrictions would put a “complete stop” to the diffusion of knowledge, promoting social progress, and keeping government informed about public opinion. It pointed out that the natives “cannot be charged with having ever abused” freedom of the press in the past, and went on to audaciously state:

Your memorialists are persuaded that the British government is not disposed to adopt the politician’s maxim so often acted upon by Asiatic Princes, that the more a people are kept in darkness, their Rulers will derive the greater advantages from them; since, by reference to History, it is found that this was but a short-sighted policy which did not ultimately answer the purpose of its authors. On the contrary, it rather proved disadvantageous to them; for we find that as often as an ignorant people, when an opportunity offered, have revolted against their Rulers, all sorts of barbarous excesses and cruelties have been the consequence … Every good Ruler, who is convinced of the imperfection of human nature, and reverences the Eternal Governor of the world, must be conscious of the great liability to error in managing the affairs of a vast empire; and therefore he will be anxious to afford every individual the readiest means of bringing to his notice whatever may require his interference. To secure this important aspect, the unrestrained Liberty of publication, is the only effectual means that can be employed. And should it ever be abused, the established Law of the Land is very properly armed with efficient powers to punish those who may be found guilty. (Collet 1988, 392–393)

The memorial was read in court, but the judge, Francis Macnaghten, dismissed it, but admitted that before the Press Ordinance was entered or its merits argued in court, he had pledged to the government that he would sanction it. The ordinance was registered in the court on 4 April 1823. The memorial was much appreciated but failed to prevent the ordinance from becoming law. The only other recourse Roy and his group had was to appeal to the King-in-Council in London. Roy then drafted another memorial, more sophisticated in its logic and arguments, and sent copies to Lord Canning (then Foreign Secretary and Leader in the House of Commons) and to the EIC’s Board of Control, in London. Over 55 numbered and lengthy paragraphs, Roy repeated the opposition to the Press Ordinance. Describing the second memorial, Collet (1988, 183) wrote: “Its stately periods and not less stately thought recall the eloquence of the great orators of a century ago. In a language and style for ever associated with the glorious vindication of liberty, it invokes against the arbitrary exercise of British power the principles and traditions which are distinctive of British history”. Continuing the rhetorical strategy of mixing fulsome praise with caution, warning and criticism, the second memorial recalled world history and put it to the King:

Men in power hostile to the Liberty of the Press, which is a disagreeable check upon their conduct, when unable to discover any real evil arising from its existence, have attempted to make the world imagine, that it might, in some possible contingency, afford the means of combination against the Government, but not to mention that extraordinary emergencies would warrant measures which in ordinary times are totally unjustifiable, your Majesty is well aware, that a Free Press has never yet caused a revolution in any part of the world because, while men can easily represent the grievances arising from the conduct of the local authorities to the supreme Government, and thus get them redressed, the grounds of discontent that excite revolution are removed; whereas, where no freedom of the Press existed, and grievances consequently remained unrepresented and unredressed, innumerable revolutions have taken place in all parts of the globe, or if prevented by the armed force of the Government, the people continued ready for insurrection. (Collet 1988, 407)

In parts of the memorial, Roy lectured to the King in polite language on the importance of freedom of the press and its relevance to the continuation of British rule in India. He also reproduced the eight restrictions under the Press Ordinance, and recalled that Friend of India, a publication by the Baptist missionaries from Serampore, had appreciated the role of the native press and had stated in a recent issue: “Nor has this liberty been abused by them [the native press] in the least degree”. Roy then eloquently pointed out that the Ordinance, issued after Buckingham’s deportation to England, gave the impression that the Indian press was being punished for the actions of one individual, and stated: “Yet notwithstanding what the local authorities of this country have done, your faithful subjects feel confident, that your Majesty will not suffer it to be believed throughout your Indian territories, that it is British justice to punish millions for the fault imputed to one individual”. A key aspect of the memorial was Roy’s recall of Mughal history and the akhbarat (newsletters) system instituted during their rule. In two paragraphs (43 and 50), the memorial regretted the new press restrictions, made veiled criticism of British rule and stated:

Your Majesty is aware, that under their former Muhammadan Rulers, the natives of this country enjoyed every political privilege in common with Mussulmans, being eligible to the highest offices in the state, entrusted with the command of armies and the government of provinces and often chosen as advisers to their Prince, without disqualification or degrading distinction on account of their religion or the place of their birth … Notwithstanding the despotic power of the Mogul Princes who formerly ruled over this country, and that their conduct was often cruel and arbitrary, yet the wise and virtuous among them, always employed two intelligencers at the residence of their Nawabs or Lord Lieutenants, Akhbar-navees, or news-writer who published an account of whatever happened, and a Khoofea-navees, or confidential correspondent who sent a private and particular account of every occurrence worthy of notice; and although these Lord Lieutenants were often particular friends of near relations to the Prince, he did not trust entirely to themselves for a faithful and impartial report of their administration, and degraded them when they appeared to deserve it, either for their own faults or for their negligence in not checking the delinquencies of their subordinate officers; which shews that even the Mogul Princes, although their form of Government admitted of nothing better, were convinced, that in a country so rich and so replete with temptations, a restraint of some kind was absolutely necessary, to prevent the abuses that are so liable to flow from the possession of power. (Collet 1988, 413, 416–417)

The memorials were an example of the confluence of themes of history, earlier Indian administrations (notably Mughal) and modern ideas, notably the utilitarianism of Jeremy Bentham, with whom Roy had been in touch. Roy cited the intelligence network of the Mughal rules to emphasise the use of various ways of communication to the rulers. At a time of weak international communication, Roy demonstrated remarkable understanding of world politics, and referred to examples to support his opposition to imposing restrictions on the press. The memorials, or public petitions, were addressed to British authorities, but drew on earlier traditions, akhbarat, of alerting the ruler to the moral infractions of his servants. In the process, Roy and his co-petitioners reframed the form and substance of the memorials but not its essential purpose that was often used in the past. This confluence of the past and the then colonial present was best exemplified by Roy, who, as Bayly (2004, 293) put it, “made in two decades an astonishing leap from the intellectual status of a late-Mughal state intellectual to that of the first Indian liberal … he independently broached themes that were being simultaneously developed in Europe by Garibaldi and Saint-Simon”.

The memorials failed to overturn the Press Ordinance; they were couched in courteous language of the time, but included covert and not-so-covert warnings that the future of British rule in India was in danger if the new rulers did not allow Indians many of the privileges available to people in England. The memorials were seen as a daring act by Roy and his group at a time when expanding colonial rule was marked by arbitrary official decisions, racism, punishment, imprisonment and the rapacious extraction of resources. But Roy took another daring step at the time: closing his Persian journal, and setting down the reasons for doing so in its last edition.

Closure of Mirat-ul-Akhbar

In his minute of 10 October 1822, Bayley devoted much attention to the contents of Roy’s Mirat-ul-Akhbar (Mirror of News) to justify demanding more powers to curb the press. Noting Roy’s “known disposition for theological controversy”, Bayley recalled an article in the journal on the death of Thomas Middleton, bishop of Calcutta. He wrote: “After some laudatory remarks on his learning and dignity the article concludes by stating that the Bishop having been now relieved from the cares and anxieties of this world, had ‘tumbled on the shoulders of the mercy of God the Father, God the Son and God the Holy Ghost’. The expression coming from a known impugner of the doctrine of the Trinity, could only be considered as ironical, and was noticed … as objectionable and offensive”. In subsequent issues, Roy went on to defend the article in his style described by Bayley as the “polemical disposition of the editor”. On 4 April 1823, the day the Press Ordinance was registered in the Supreme Court and became law, Roy closed Mirat-ul-Akhbar in protest. In the final issue, he set out the reasons for doing so:

Under these circumstances, I, the least of all the human race, in consideration of several difficulties, have, with much regret and reluctance, relinquished the publication of this Paper (Mirat-ool-Ukhbar). The difficulties are these:

First—Although it is very easy for those European Gentlemen, who have the honour to be acquainted with the Chief Secretary to Government, to obtain a License according to the prescribed form; yet to a humble individual like myself, it is very hard to make his way through the porters and attendants of a great Personage; or to enter the doors of the Police Court, crowded with people of all classes, for the purpose of obtaining what is in fact, already [? Unnecessary] in my own opinion. As it is written—Abrooe kih ba-sad khoon i jigar dast dihad

Ba-oomed-I karam-e, kha’jah, ba-darban ma-farosh

(The respect which is purchased with a hundred drops of heart’s blood

Do not thou, in the hope of a favour commit to the mercy of a porter).

Secondly—To make Affidavit in an open court, in presence of respectable Magistrates, is looked upon as very mean and censurable by those who watch the conduct of their neighbours. Besides, the publication of a newspaper is not incumbent upon every person, so that he must resort to the evasion of establishing fictitious Proprietors, which is contrary to Law, and repugnant to Conscience.

Thirdly—After incurring the disrepute of solicitation and suffering the dishonour of making Affidavit, the constant apprehension of the License being recalled by Government which would disgrace the person in the eyes of the world, must create such anxiety as entirely to destroy his peace of mind, because a man, by nature liable to err, in telling the real truth cannot help sometimes making use of words and selecting phrases that might be unpleasant to Government. I, however, here prefer silence to speaking out:Guda-e goshah nashenee to Khafiza makharosh

Roo mooz maslabat-i khesh khoosrowan danand

(Thou O Hafiz, art a poor retired man, be silent,

Princes know the secrets of their own Policy).

I now entreat those kind and liberal gentlemen of Persia and Hindoostan, who have honoured the Mirat-ool-Ukhbar with their patronage, that in consideration of the reasons above stated, they will excuse the non-fulfilment of my promise to make them acquainted with passing events.

Once again, the confluence of themes of religion, language, personal honour rooted in the past and the colonial present are evident in Roy’s last note to his readers. He invoked Persian couplets to make courteous attacks on the British and the restrictions imposed in the Press Ordinance. He pointed out the differential access Indians and the British had to officials of the Company government, and recalled the embarrassment rooted in religion and tradition faced by Indians to the act of taking an oath. Taken together, even though the two memorials and closing Roy’s journal were couched in courteous terms and some rhetoric, they were essentially an act of political defiance, which was delivered in the language and discourse of the new rulers. The opposition to the Press Ordinance won new converts among the British (such as Lieutenant Colonel Leicester Stanhope), and provided a template for future political opposition on other issues, such as the controversial Jury Act, Indian property and labour, the rights of Britons in India, taxes, education and making English the medium of instruction.

Conclusion

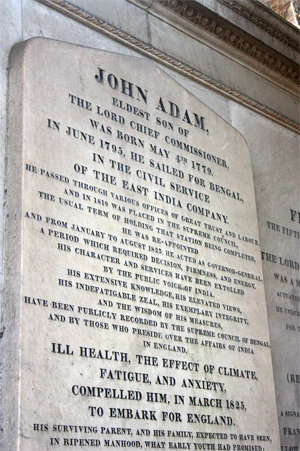

Roy closing his journal in protest and the two memorials did not succeed in changing policy, but their significance lies in the ways in which the colonial authorities dealt with the press subsequently. The memorials were much appreciated in England, where Buckingham had continued his campaign in print against the EIC and its exercise of arbitrary powers in India. Lord Amhurst, who took over from John Adam as the governor-general of India in 1823 (he was in office until 1828) did not implement the Press Ordinance rigorously, neither did his successor, Lord Bentinck. The memorials, closure of Roy’s journal and Buckingham’s activities in London had generated much publicity on the issue of freedom of the press in colonial India, with governors-general choosing to avoid taking major action against the fast growing press. In 1835, it was another acting governor-general, Charles Metcalfe, who, aided by Macaulay, removed Adam’s licensing and other restrictions on the press through Act No. XI. By then, the idea of a free press had become a key element of a growing public sphere in Calcutta and elsewhere in colonial India. Metcalfe, who was later penalised by EIC authorities in London for removing the press restrictions, was hailed as a liberator of press and immortalised in Metcalfe Hall, a major landmark in Calcutta, which was built with public subscription in the style of imposing empire architecture in his honour. The press had become a key site of discussion and protest as the Company government introduced new laws and initiatives to govern India. The largely permissive situation for the press continued until the 1857 rebellion, by when opinions and positions had hardened on both sides, as Indian journals openly criticised the British and the EIC imposed new restrictions on the press.

But the press had grown all over colonial India, despite new repressive measures. As Majumdar (1965, 233) put it, “[The] daring act of Rammohan and his five associates marks the beginning of a new type of political activity which was destined to be the special characteristic of India for nearly a century”. The significance of Roy’s two memorials was highlighted soon after the Round Table Conference was held in London in 1930–1931 to discuss India’s future: “It might never have come about had the great Ram Mohan Roy not taken the lead, and three Tagores, a Ghose, and a Banerji, not joined him in the starting the process that led to it” (O’ Malley 1941, 198). This forgotten chapter of protest focused on the idea of a free press provides a key insight into the continuation of politics as the dominant theme in Indian journalism today. Politics and political protest occupied the centre-stage in early Indian journalism, and continued during the long freedom struggle, which further entrenched politics as the dominant theme, which continued after independence, up to the present. The form, structure and discourse of politics in Indian journalism has changed, reflecting corresponding changes in political structures and themes, but the symbiotic link between journalism and politics in India has never been in question.

DISCLOSURE STATEMENT

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

NOTE

1. British/Colonial spellings have been used for people and places in the paper.

REFERENCES

Adam, John. 1822. Minute No. 3, British Library, Bengal Public Consultations, P/10/55.

Barns, Margarita. 1940. The Indian Press: A History of the Growth of Public Opinion in India. London: Allan & Unwin.

Bayley, W. B. 1822. Minute No. 8, British Library Bengal Public Consultations, P/10/55.

Bayly, C. A. 2004. The Birth of the Modern World: 1780–1914. Oxford: Blackwell.

Collet, Sophia D. 1988. The Life and Letters of Raja Rammohun Roy. Calcutta: Sadharan Brahmo Samaj.

Dharwadker, Vinay. 1997. “Print Culture and Literary Markets in Colonial India.” In Language Machines: Technologies of Literary and Cultural Production, edited by Jeffrey Masten, Peter Stallybrass, and Nancy J. Vickers, 108–133. London: Routledge.

Gaonkar, Dilip P. 1999. “On Alternative Modernities.” Public Culture 11 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1215/ 08992363-11-1-1.

Majumdar, R. C. 1965. British Paramountcy and Indian Renaissance. Part II. Bombay: Bharatiya Vidya Bhavan.

Marshall, P. J. 2000. “The White Town of Calcutta under the Rule of the East India Company.” Modern Asian Studies 34 (2): 307–331. doi:10.1017/S0026749X00003346.

Mills, J. S. 1924. The Press and Communications of the Empire’. London: W. Collins Sons.

O’Malley, L. S. S. 1941. Modern India and the West: A Study of the Interaction of Their Civilisations. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Raichaudhuri, Tapan. 1988. Europe Reconsidered: Perceptions of the West in Nineteenth Century Bengal. New Delhi: Oxford University Press.

Sen, Amartya. 2005. The Argumentative Indian. London: Allen Lane.

Shaw, Graham. 1981. Printing in Calcutta to 1800. London: The Bibliographical Society.

Sonwalkar, Prasun. 2002. “Murdochization of the Indian Press: From By-line to Bottom-line.” Media Culture & Society 24 (6): 821–834. doi:10.1177/016344370202400605.

Sonwalkar, Prasun. 2014. “Narendra Modi’s Victory Compared to ‘1979 Thatcher Moment’ in UK.” Hindustan Times, June 2.