Amaravati Stupaby Wikipedia

Accessed: 6/20/24

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Amaravati_StupaFrailin

Amaravati Stupa

Depiction of the stupa, from the site

Location Amaravathi, Andhra Pradesh, India

Coordinates 16.5753°N 80.3580°E

Height originally perhaps 73 m (241 ft)

Built 3rd Century BCE

Ruins of the stupa, 2012

Ruins of the stupa, 2012 A model of the original stupa, final phase, as reconstructed by archaeologists

A model of the original stupa, final phase, as reconstructed by archaeologistsAmarāvati Stupa is a ruined Buddhist stūpa at the village of Amaravathi, Palnadu district, Andhra Pradesh, India, probably built in phases between the third century BCE and about 250 CE. It was enlarged and new sculptures replaced the earlier ones, beginning in about 50 CE.[1] The site is under the protection of the Archaeological Survey of India, and includes the stūpa itself and the Archaeological Museum.[2]

The surviving important sculptures from the site are now in a number of museums in India and abroad; many are considerably damaged. The great majority of sculptures are in relief, and the surviving sculptures do not include very large iconic Buddha figures, although it is clear these once existed. The largest collections are the group in the Government Museum, Chennai (along with the friezes excavated from Goli), that in the Amaravati Archaeological Museum, and the group in the British Museum in London. Others are given below.[3]

Art historians regard the art of Amaravati as one of the three major styles or schools of ancient Indian art, the other two being the Mathura style, and the Gandharan style.[4] Largely because of the maritime trading links of the East Indian coast, the Amaravati school or Andhra style of sculpture, seen in a number of sites in the region, had great influence on art in South India, Sri Lanka and South-East Asia.[5]

Like other major early Indian stupas, but to an unusual extent, the Amaravarti sculptures include several representations of the stupa itself, which although they differ, partly reflecting the different stages of building, give a good idea of its original appearance, when it was for some time "the greatest monument in Buddhist Asia",[6] and "the jewel in the crown of early Indian art".[7]

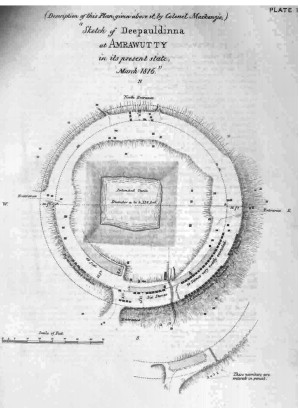

Name of the siteThe name Amaravathi is relatively modern, having been applied to the town and site after the Amareśvara Liṅgasvāmin temple was built in the eighteenth century.[8] The ancient settlement, just next to the modern Amaravathi village, is now called Dharanikota; this was a significant place in ancient times, probably a capital city. The oldest maps and plans, drawn by Colin Mackenzie and dated 1816, label the stūpa simply as the deepaladimma or 'hill of lights'.[9] The monument was not called a stūpa in ancient inscriptions, but rather the mahācetiya or great sanctuary.[10]

HistoryThe stupa, or mahāchetiya, was possibly founded in the third century BCE in the time of Asoka but there is no decisive evidence for the date of foundation.[11] The earliest inscription from the site belongs to the early centuries BCE but it cannot be assigned to Aśoka with certainty.[12] The earliest phase from which we have architectural or sculpted remains seems to be post-Mauryan, from the 2nd century BCE.[13]

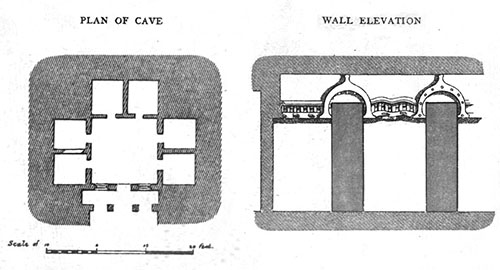

The main construction phases of Amaravati fall in two main periods, with the stupa enlarged in the second by additions to the main solid earth mound, faced with brick, consisting of railings (vedikā) and carved slabs placed around the stūpa proper. As elsewhere these slabs are usually called 'drum slabs' because they were placed round the vertical lower part or "drum" (tholobate) of the stūpa. In the early period (circa 200-100 BCE), the stūpa had a simple railing consisting of granite pillars, with plain cross-bars, and coping stones. The coping stones with youths and animal reliefs, the early drum slabs, and some other early fragments belong to this period. The stūpa must have been fairly large at this time, considering the size of the granite pillars (some of which are still seen in situ, following excavations).[14]

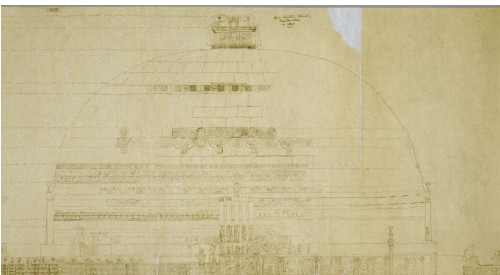

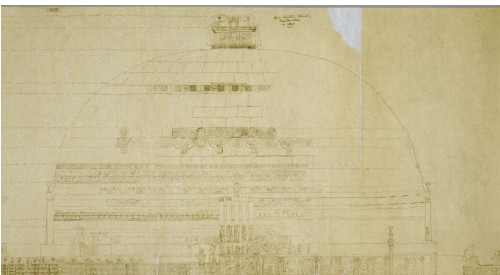

Reconstruction of the Amaravati Stupa, by or after Sir Walter Elliott 1845.[15]

Reconstruction of the Amaravati Stupa, by or after Sir Walter Elliott 1845.[15]The late period of construction started around ca. 50 BCE and continued until circa 250 CE. The exterior surfaces of the stupa and the railings were in effect all new, with the old elements reused or discarded. James Burgess in his book of 1887 on the site, noted that:[16]

wherever one digs at the back of the outer rail, broken slabs, statues &etc, are found jammed in behind it. The dark slate slabs too of the procession path are laid on a sort of concrete formed of marble chips, broken slabs, pillars &etc ...

At the base the dome seems to have been brought out by 2.4 metres all round, the distance between the outer face of the old drum wall, and that of the new one. The older wall was 2.4 metres thick and the new one 1.2 metres. The size and shape of the new dome is uncertain.[17]

The earlier vedika railings were also replaced with larger ones, with more sculpture. Some of the old stones were recycled elsewhere on the site. The pillars had mostly been plain, but there was a coping carved in relief at the top.[18] Burgess estimated that the new railings were some 3 metres tall, 59 metres in diameter, with 136 pillars and 348 crossbars, running for 803 feet in total.[19]

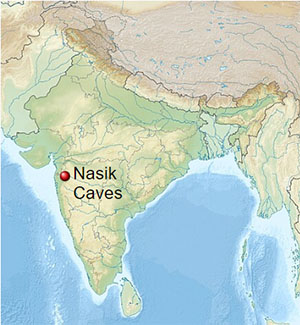

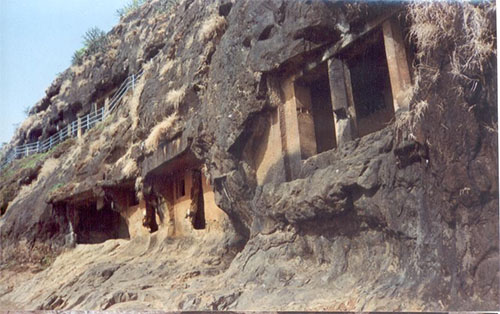

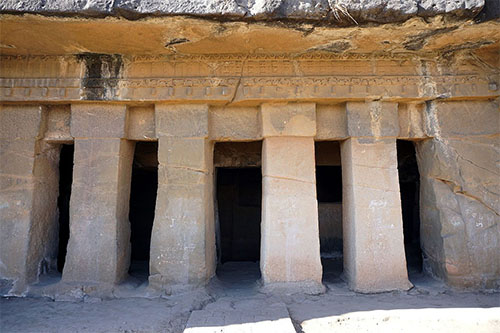

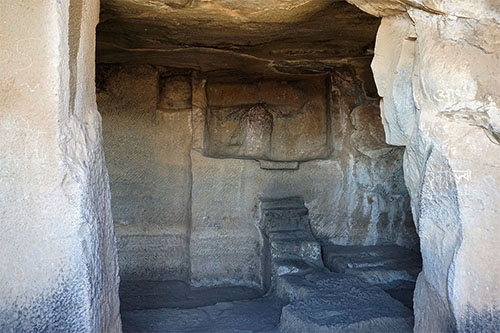

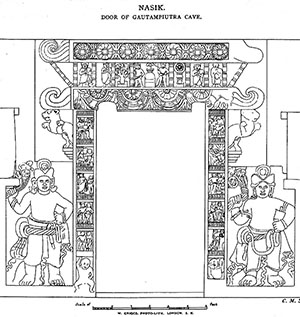

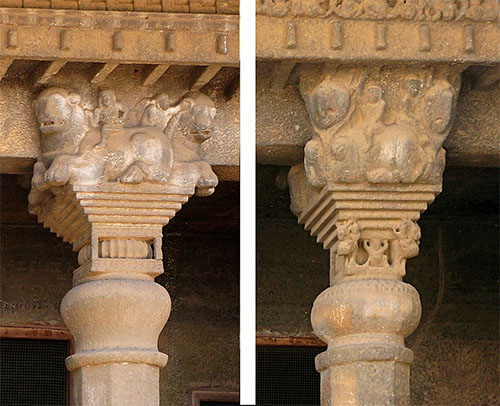

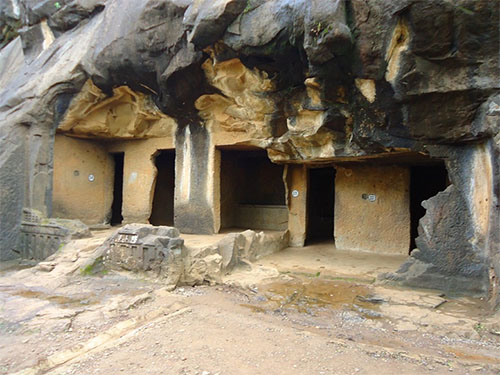

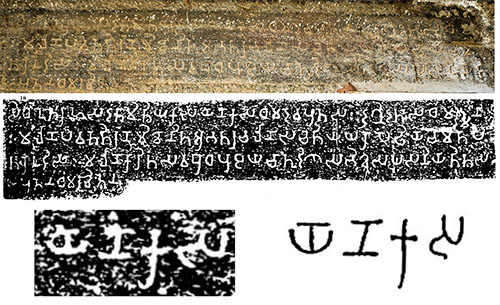

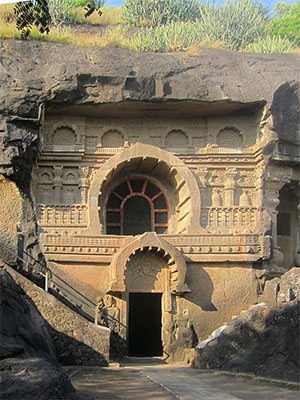

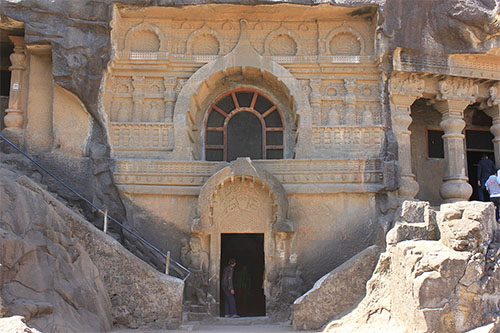

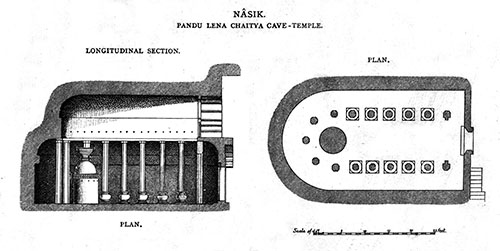

The work of this period has generally been divided into three phases on the basis of the styles and content of the railing sculpture and so dates that can be assigned to parts of the great limestone railing.[20] Shimada dates the first phase to 50-1 BCE, about the same period as the Sanchi stūpa I gateways. The second phase is 50-100 CE, the same period as Karli chaitya and the Pandavleni Caves (no. 3 and 10) at Nasik. The third phase is circa 200-250 CE based on comparisons with Nagarjunakonda sculpture. Some other types of sculpture belong to an even later time, about the seventh or eighth centuries, and include standing Bodhisattvas and goddesses. Amaravātī continued to be active after this time, probably to about the thirteenth century.

The Chinese traveller and Buddhist monk Hiuen Tsang (Xuanzang) visited Amaravati in 640 CE, stayed for some time and studied the Abhidhammapitakam. He wrote a enthusiastic account of the place, and the viharas and monasteries there.[21] It was still mentioned in Sri Lanka and Tibet as a centre of Esoteric Buddhism as late as the 14th century.[22]

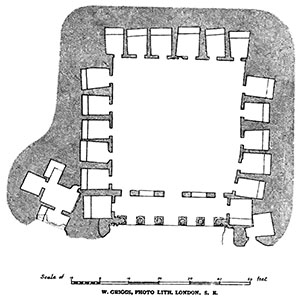

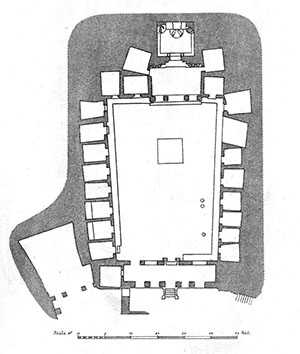

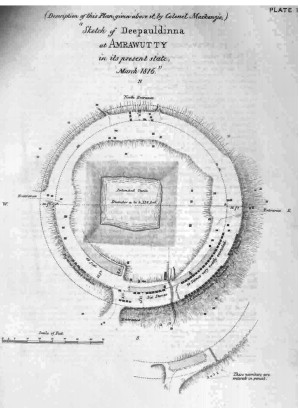

Plan of the Amaravati Stupa as sketched by Colin Mackenzie in 1816.[23]

Plan of the Amaravati Stupa as sketched by Colin Mackenzie in 1816.[23]During the period of the decline of Buddhism in India, the stupa was neglected and was buried under rubble and grass. A 14th-century inscription in Sri Lanka mentions repairs made to the stupa, and after that it was forgotten. The stupa is related to the Vajrayana teachings of Kalachakra, still practiced today in Tibetan Buddhism.[24] The Dalai Lama of Tibet conducted a Kalachakra initiation at this location in 2006, attended by over 100,000 pilgrims.[25]

RecoveryWesterners were first alerted to the ruins of the Stupa at Amaravati after a visit in 1797 by Major Colin Mackenzie.[26] On the right bank of the Krishna River[27] in the Andhra district of southeast India, Mackenzie came across a huge Buddhist construction built of bricks and faced with slabs of limestone.[28] By the time he returned in 1816, indiscriminate excavations led by the powerful local zamindar Vasireddy Venkatadri Nayudu had already destroyed what remained of the structure and many of the stones and bricks had been reused to build local houses.[26] Mackenzie carried out further excavations, recorded what he saw and drew a plan of the stupa.[29]

In 1845, Sir Walter Elliot of the Madras Civil Service explored the area around the stupa and excavated near the west gate of the railing, removing many sculptures to Madras (now Chennai). They were kept outside the local college before being transported to the Madras Museum. At this time India was run by the East India Company and it was to that company that the curator of the museum appealed. The curator Dr Edward Balfour was concerned that the artefacts were deteriorating so in 1853 he started to raise a case for them to be moved. Elliot seems to have made extensive notes and sketches of his excavations, but most of these were lost getting back to England.[30]

Excavation of the south gate of the stupa by J.G. Horsfall in 1880.[31]

Excavation of the south gate of the stupa by J.G. Horsfall in 1880.[31]By 1855, he had arranged for both photographs and drawings to be made of the artifacts, now called the Elliot Marbles. 75 photographs taken by Captain Linnaeus Tripe are now in the British Library. Many of the sculptures were exported to London in 1859,[32] though more remained in Madras. Robert Sewell, under James Burgess, first Director of the Archaeological Survey of India, made further excavations in the 1880s, recording his excavations in some detail with drawings and sketches but not in the detail that would now be expected.[26]

Plans have also been put in place to create a purpose built exhibition space for the sculptures still in India. Those marbles not in an air-conditioned store were said to show signs of damage from the atmosphere and salt.[32] The Chennai museum has plans for an air-conditioned gallery to install the sculptures, but these goals have yet to be realised.[33]

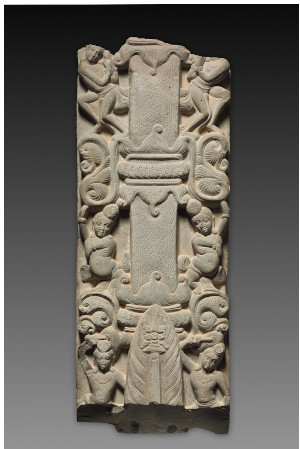

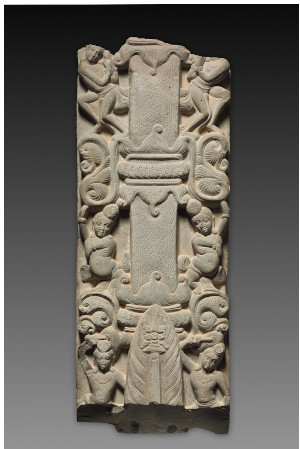

Sculptures Later period railing pillar, incomplete at top

Later period railing pillar, incomplete at topThe history of the sculptures for the stupa is complicated and scholarly understanding of it is still developing. The subject matter of many detailed narrative reliefs is still unidentified,[34] and many reliefs of the first main phase round the drum were turned round in the second, and recarved on their previously plain backs, before being re-mounted on the drum. The earlier sculptures, now invisible and facing into the stupa, were often badly abraded or worn down in this position.[35]

In the final form of the stupa, it seems that all the sculpture of the early phase was eventually replaced, and new sculpture added in positions where there had been none before, giving a profusion of sculpture, both relief and free-standing, on the stupa itself, and the vedika railings and gateways surrounding it, making Amaravati "the most richly decorated stupa known".[36]

The final form of the railings had a diameter of 192 feet. The railing uprights were some 9 feet high, with three rounded cross-bars horizontally between them, and a coping at the top. Both uprights and cross-bars were decorated with round medallion or tondo reliefs, the latter slightly larger, and containing the most impressive surviving sculpture. Large numbers of the medallions contained just a single stylized lotus flower. The vedika had four entrances, at the cardinal directions, and here the railings turned to run away from the stupa.[37]

All this is much the same as at Sanchi, the surviving highly decorated stupa that is in the closest to its original condition. But the Sanchi railings have much less decoration, except around the famous torana gateways; these do not seem to have been a feature at Amaravati.

Types of sculptureVery little of the sculpture was found and properly recorded in its original exact location, but the broad arrangement of the different types of pieces is generally agreed. The many representations of a stupa, either representing the Amaravati Stupa itself, or an imaginary one very similar to it, provide a useful guide. It is not certain whether either the early or late phases of sculptural decoration were ever completed, as too much has been destroyed. Most survivals can be fitted into groups, by architectural function and placement.

A typical "drum-slab" is about 124 centimetres high, 86 cm wide and 12.5 cm thick. A two-sided example in the British Museum is dated by them to the 1st century BCE for the obverse face, with a scene of worshippers around the Bodhi Tree with no Buddha shown, and 3rd century CE for the reverse face, with a view of a stupa,[38] which large numbers of the later drum-slabs show. The stupas are broadly consistent and are generally taken to show what the late form of the Amaravati Stupa looked like, or was intended to.

Reconstructed section of the later railing at the site museum

Reconstructed section of the later railing at the site museumThe early railing pillars are in granite (apparently only on the east and west sides) and plain; the cross-bars were perhaps in limestone. Many stumps of the pillars are now arranged around the stupa. Fragments have been found of limestone coping stones, some with reliefs of running youths and animals, similar in style to those at Bharhut, so perhaps from c. 150-100 BCE.[39] This subject-matter continued in the coping stones of the first phase of the later railings.

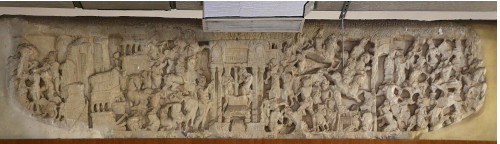

The later "railing copings" (uṣṇīṣa) are long pieces typically about 75 to 90 cm tall and 20 to 28 cm thick,[40] running along the top of the railings (where perhaps their detail was hard to make out). Many are carved with crowded scenes, often illustrating Jataka tales from the previous lives of the Buddha. The early coping stones were smaller and mostly carved with a thick undulating garland with small figures within its curves.

Coping stone relief, late, inner face

Coping stone relief, late, inner faceThere was also a much smaller set of limestone railings, undecorated, whose placing and function remains unclear.[41] The later ones, in limestone, are carved with round lotus medallions, and sometimes panels with figurative reliefs, these mostly on the sides facing in towards the stupa. There are three medallions to a column, the bottom one incomplete. Based on the style of the sculpture the construction of the later railing is usually divided into three phases, growing somewhat in size and the complexity of the images.[42]

Around the entrances there were a number of columns, pillars and pilasters, some topped with figures of sitting lions, a symbol of Buddhism. Several of these have survived. There are also small pilasters at the side of some other reliefs, especially drum-slabs showing stupas. The stupas on drum-slabs show large statues of a standing Buddha behind the entrances, but none of these have survived. Only a few fragments from the garland decorations shown high on the dome in drum-slab stupa depictions (one in Chennai is illustrated).

Later railing pillar, inner face

Later railing pillar, inner face  Early drum slab, with king and boy, and fragment of the relief decoration high on the dome

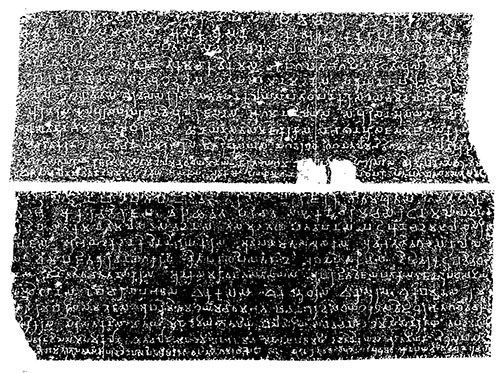

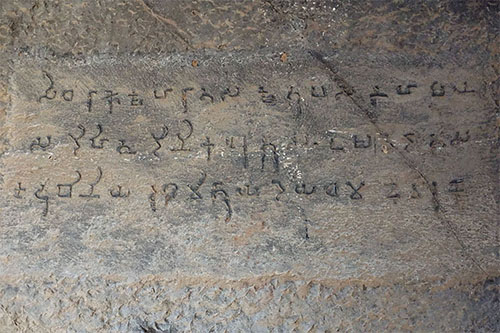

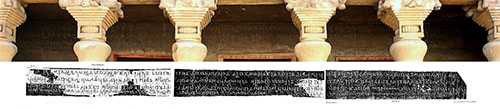

Early drum slab, with king and boy, and fragment of the relief decoration high on the dome  Drum-slab, later period, inscribed "(Adoration) to Siddhartha! Gift of coping stone to the great stupa of the Lord by the wife of the merchant Samudra, the son of the householder Samgha, living in the chief city of Puki district and by the ... householder Kotachandi for welfare and happiness of the world."[43]

Drum-slab, later period, inscribed "(Adoration) to Siddhartha! Gift of coping stone to the great stupa of the Lord by the wife of the merchant Samudra, the son of the householder Samgha, living in the chief city of Puki district and by the ... householder Kotachandi for welfare and happiness of the world."[43]  Railing medallion with figures, including an aniconic Great Departure, and the worship of the Buddha's hair or turban, c. 150

Railing medallion with figures, including an aniconic Great Departure, and the worship of the Buddha's hair or turban, c. 150  Worship of the Buddha's bowl in heaven, c. 150

Worship of the Buddha's bowl in heaven, c. 150  Buddha Preaching in Tushita Heaven

Buddha Preaching in Tushita Heaven  Coping stone relief with garland bearers

Coping stone relief with garland bearers  "Vase of plenty" drum-slab, late

"Vase of plenty" drum-slab, late  Railing cross-bar medallion, late

Railing cross-bar medallion, late  Pilaster fragment, late, Veneration of the Buddha as a Fiery Pillar

Pilaster fragment, late, Veneration of the Buddha as a Fiery Pillar  Drawing of pillar fragments, c. 1853

Drawing of pillar fragments, c. 1853  Lion, from the top of a columnAmaravati School or style

Lion, from the top of a columnAmaravati School or style Buddha statue at Nagarjunakonda

Buddha statue at NagarjunakondaAmaravati itself is the most important site for a distinct regional style, called the Amaravati School or style, or Andhran style. There are numerous other sites, many beyond the boundaries of the modern state of Andhra Pradesh. One reason for the use of the terms Amaravati School or style is that the actual find-spot of many Andhran pieces is uncertain or unknown. The early excavations at Amaravati itself were not well recorded, and the subsequent history of many pieces is uncertain.[44] As late as the 1920s and beyond, other sites were the subject of "excavations" that were sometimes little better than treasure hunts, with pieces sold abroad as "Amaravati School".[45]

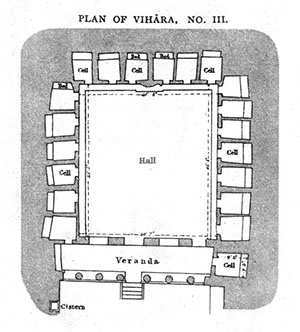

The second most important site for the style is Nagarjunakonda, some 160 km away. This was a large monastic vihara or "university", which is now submerged under a lake, after construction of a dam. Many remains were relocated to what is now an island in the lake, but most sculptures are now in various museums, in India and abroad.[46] The Chandavaram Buddhist site is another large stupa.

In reliefs, the mature Amaravati style is characterised by crowded scenes of "graceful, elongated figures who imbue the sculpted scenes with a sense of life and action that is unique in Indian art";[47] "decorative elements reach a suave richness never surpassed... In the narrative scenes, the deep cutting permits overlapping figures on two or even three planes, the figures appearing to be fully in the round. The superlative beauty of the individual bodies and the variety of poses, many realizing new possibilities of depicting the human form, as well as the swirling rhythms of the massed compositions, all combine to produce some of the most glorious reliefs in world art".[48]

Though the subject matter is similar to that at Bharhut and Sanchi "the style is notably different. Compared with the northern works, their figures are more attenuated and sensual, their decoration more abundant. Empty space is anathema, so that the entire surface is filled with figures in motion".[49]

In earlier phases, before about 180-200 CE, the Buddha himself is not shown, as also in other Indian schools.[50] Unlike other major sites, minor differences in the depiction of narratives show that the exact textual sources used remain unclear, and have probably not survived.[51]

Especially in the later period at Amaravati itself, the main relief scenes are "a sort of 'court art'", showing a great interest in scenes of court life "reflecting the luxurious life of the upper class, rich, and engaged in the vibrant trade with many parts of India and the wider world, including Rome".[52]

Free-standing statues are mostly of the standing Buddha, wearing a monastic robe "organized in an ordered rhythm of lines undulating obliquely across the body and imparting a feeling of movement as well as reinforcing the swelling expansiveness of the form beneath". There is a "peculiarly characteristic" large fold at the bottom of the robe, one of a number of features similar to the Kushan art of the north.[53]

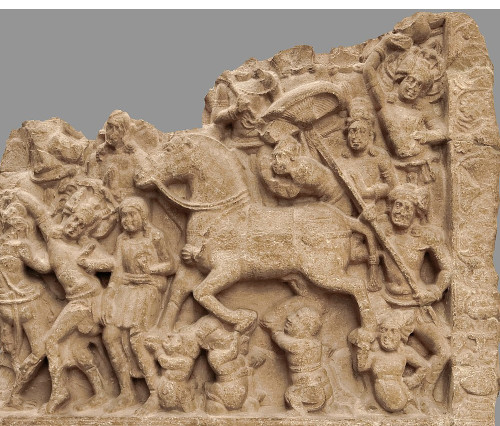

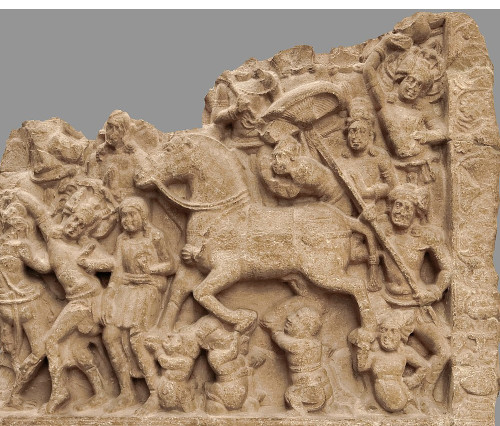

A representation of Mara's assault on the Buddha, depicted in aniconic form, 2nd century AD, now thought to come from Nagarjunakonda

A representation of Mara's assault on the Buddha, depicted in aniconic form, 2nd century AD, now thought to come from Nagarjunakonda  The Great Departure, 2nd century, aniconic

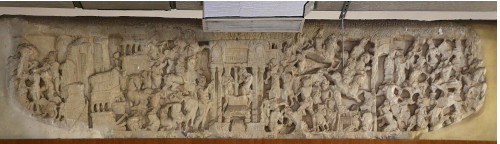

The Great Departure, 2nd century, aniconic  Life scenes of Buddha-2nd century CE, left panel

Life scenes of Buddha-2nd century CE, left panel  Life scenes of Buddha-2nd century, middle panel

Life scenes of Buddha-2nd century, middle panel  Life scenes of Buddha-2nd century CE, right panelDating and ruling dynasties

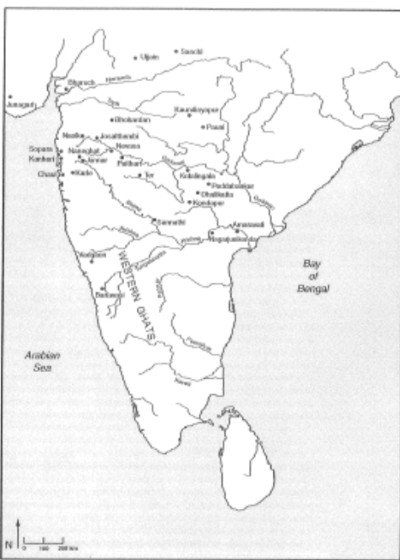

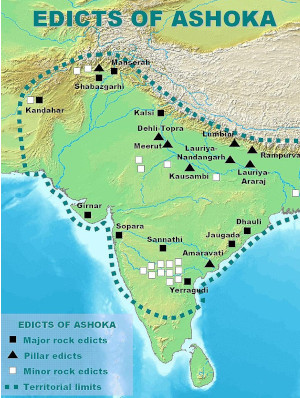

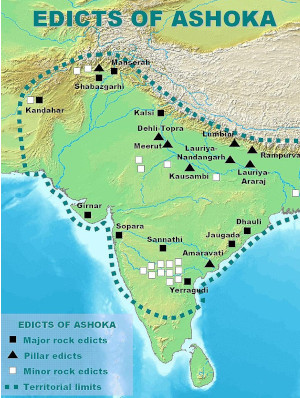

Life scenes of Buddha-2nd century CE, right panelDating and ruling dynasties Distribution of the Edicts of Ashoka[54]

Distribution of the Edicts of Ashoka[54]From the 19th century, it was always thought that the stupa was built under the Satavahana dynasty, rulers of the Deccan whose territories eventually straddled both east and west coasts. However, this did not resolve the dating issues, as the dates of that dynasty were uncertain, especially at the start. Recently there has been more attention paid to the preceding local Sada dynasty, perhaps tributaries of the Mahameghavahana dynasty ruling Kalinga to the north. Their capital was probably Dhanyakataka; the stupa was just outside this.[55]

Since the 1980s, the dynasty has been given this name as all the names of kings from it, known from coins and inscriptions, end in "-sada" (as all from the later Gupta dynasty end in that).[56] They perhaps began to rule around 20 BCE.[57] Their coins nearly all have a standing lion, often with symbols that are very likely Buddhist.[58] Shimada suggests that much or most of the sculpture at Amaravati was created under Sada rule, before the Satavahanas took over in the 2nd century CE,[59] possibly around 100 CE.[60]

At the later end of the chronology, the local Andhra Ikshvaku ruled after the Satavahanas and before the Gupta Empire, in the 3rd and early 4th centuries, perhaps starting 325-340.[61]

The Colin Mackenzie album Around the stupa wall in 2011: early granite railing pillar fragments, lotus flower medallions, & a large drum casing fragment with pilasters

Around the stupa wall in 2011: early granite railing pillar fragments, lotus flower medallions, & a large drum casing fragment with pilastersThis album of drawings of Amarāvati is a landmark in the history of archaeology in India. The pictures were made in 1816 and 1817 by a team of military surveyors and draftsmen under the direction of Colonel Colin Mackenzie (1757-1821), the first Surveyor-General of India.[62]

The album contains maps, plans and drawings of sculpture from the stūpa at Amarāvati. The album is preserved in the British Library, where it is online,[63] with a second copy in Kolkata.

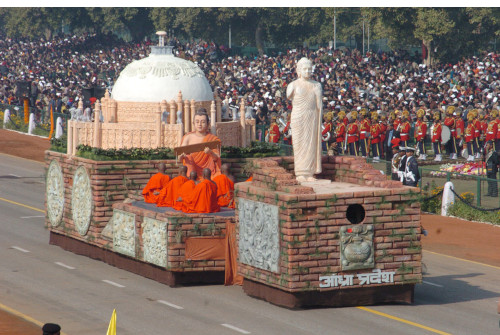

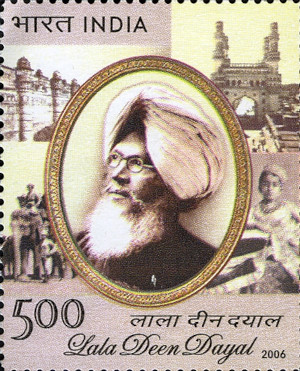

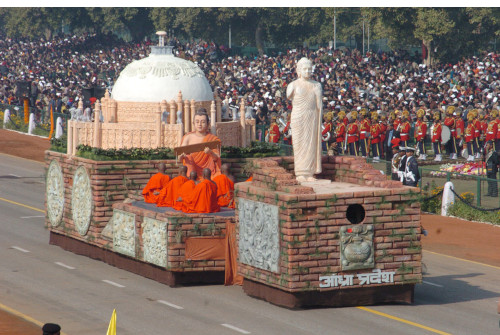

Amarāvati sculptures worldwide Tableau of Andhra Pradesh's 'Buddhist Heritage' in the Republic Day parade, 2006, New Delhi, the Great Stupa of Amaravati and the statue of Buddha along with Acharya Nagarjuna teaching his disciples

Tableau of Andhra Pradesh's 'Buddhist Heritage' in the Republic Day parade, 2006, New Delhi, the Great Stupa of Amaravati and the statue of Buddha along with Acharya Nagarjuna teaching his disciplesApart from those in the site museum (some of which are casts), nearly all of the sculptures have been removed from the site of the stupa. Some pieces, especially from the early granite railing pillars, and lotus flower medallions, are placed around the stupa itself. Apart from the museum at the site, several museums across India and around the world have specimens from Amarāvati.[64] The largest collections are the group in the Government Museum, Chennai, and the group in the British Museum in London. Significant collections of sculpture are held in the following places:[65]

India• Government Museum, Chennai[66]

• Archaeological Museum, Amaravathi[2]

• Indian Museum, Kolkata

• National Museum of India, New Delhi[67]

• State Museum, Hyderabad

• Patna Museum, Patna

• Chhatrapati Shivaji Maharaj Vastu Sangrahalaya, Mumbai[68]

• State Museum, Pudukkottai

• Baudhasree Archaeological Museum, Vijayawada

• State Museum Lucknow, Lucknow

United Kingdom• The British Museum, London (see Amaravati Marbles)[69]

France• Guimet Museum

Singapore• Asian Civilisations Museum, Singapore[70]

United States• University of Pennsylvania Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Philadelphia[71]

• Museum of Fine Arts, Boston[72]

• Freer Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[73]

• Seattle Art Museum, Seattle

• also Cleveland, Chicago, and Kansas City

See also• List of tallest structures built before the 20th century

Notes1. Shimada, 74

2. "Archaeological Museum, Amaravati - Archaeological Survey of India".

3. PDF List from the BASAS Project

4. Pal, Pratapaditya (1986). Indian Sculpture: Circa 500 B.C.-A.D. 700. Los Angeles County Museum of Art. p. 154. ISBN 978-0-520-05991-7.

5. Rowland, 210

6. Harle, 35

7. Harle, 34

8. South Indian transliteration differs from Hunterian transliteration, thus Amarāvatī can appear as Amarāvathī, Ratana as Rathana, etc.

9. For link to maps and plans at the British Library: The Amaravati Album

10. Pia Brancaccio, The Buddhist Caves at Aurangabad: Transformations in Art and Religion (Leiden: Brill, 2011), p. 47.

11. Shimada, 66

12. See Harry Falk, Aśokan Sites and Artefacts: A Source-Book with Bibliography (Mainz: Von Zabern, 2006).

13. Shimada, 72

14. Shimada, 72-74

15. see BM, 6

16. quoted, Shimada, 71, from The Buddhist Stupar of Amaravati and Jaggayyapeta in the Krishna District, Piadras Presidency, surveyed in 1882, published Trubner, 1887

17. Shimada, 82

18. Shimada, 64, plates 5-12

19. Shimada, 82

20. Shimada, 82-83, for Shimada see Akira Shimada

21. Travels of Xuanzang

22. BM, 1

23. see BM, 3

24. Kilty, G Ornament of Stainless Light, Wisdom 2004, ISBN 0-86171-452-0

25. Becker, 6

26. Buddha, ancientindia.co.uk, retrieved 19 December 2013

27. Erdosy, George; et al. (1995). The archaeology of early historic South Asia: the emergence of cities and states (1. publ. ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 146. ISBN 0521376955.

28. Amravati, PilgrimTrips, retrieved 12 January 2014

29. Government Museum Website Government Museum homepage (and then click on "Archaeology", Chennai Museum, Tamil Nadu, retrieved 11 January 2014

30. Shimada, 88

31. BM, 5

32. Roy, Amit (December 1992). "Out of Amatavati". IndiaToday. Retrieved 21 December 2013.

33. "History in stone". The Hindu. 28 January 2002. Archived from the original on 14 February 2002. Retrieved 22 December 2013.

34. BM, 48-57

35. Becker, 7-9; Shimada, 71; Shimada, plates 20 and 21 illustrate both sides of an example.

36. Fisher, 40 (see 197-200 on Borobudor for why this is presumably excluded from comparison).

37. Harle, 35

38. "drum-slab" (BM 1880,0709.79)

39. Shimada, 66-69, 72

40. Averaging BM 1880,0709.18 and BM 1880,0709.19

41. Shimada, 69-70

42. Shimada, 82-84

43. Government Museum, Chennai

44. BM, 2-6, 89

45. BM, 7, 97

46. Rowland, 212-213

47. Craven, 76

48. Harle, 79

49. Fisher, 51

50. Craven, 77; Harle, 38

51. BM, 48-50

52. BM, 46

53. Rowland, 209

54. "India: The Ancient Past" p.113, Burjor Avari, Routledge, ISBN 0-415-35615-6

55. BM, 46

56. BM, 38-39

57. BM, 41

58. BM, 38, 41-45

59. BM, 10

60. BM, 40

61. Shimada, 48-58

62. Howes, Jennifer (2002). "Colin Mackenzie and the Stupa at Amaravati". South Asian Studies. 18: 53–65. doi:10.1080/02666030.2002.9628607. S2CID 194108928.

63. link to the British Library album

64. These collections are being brought together in the World Corpus of Amarāvatī Sculpture, a digital project agreed to and jointly developed by the Archaeological Survey of India and the British Academy, London. website Archived 23 October 2016 at the Wayback Machine, another site, little developed

65. A fuller list, from BASAS

66. "Government Museum Chennai".

67. "National Museum, New Delhi".

68. Virtual Museum of Images and Sound - VMIS. "Collections-Virtual Museum of Images and Sounds".

69. "British Museum - Room 33a: Amaravati". British Museum.

70. "Singapore And India Sign Agreement : Ministry of Information, Communications and The Arts Press Release, 1 March 2003".

71. "Search Results for: Amaravati - Penn Museum Collections".

72. "Search". Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

73. "Object - Online - Collections - Freer and Sackler Galleries". Freer - Sackler. Archived from the original on 22 December 2015. Retrieved 30 October 2015.

References • Becker, Catherine, Shifting Stones, Shaping the Past: Sculpture from the Buddhist Stūpas of Andhra Pradesh, 2015, Oxford University Press, ISBN 9780199359400

• "BM": Amaravati: The Art of an Early Buddhist Monument in Context, Edited by Akira Shimada and Michael Willis, British Museum, 2016, PDF

• Craven, Roy C., Indian Art: A Concise History, 1987, Thames & Hudson (Praeger in USA), ISBN 0500201463

• Fisher, Robert E., Buddhist art and architecture, 1993, Thames & Hudson, ISBN 0500202656

• Harle, J.C., The Art and Architecture of the Indian Subcontinent, 2nd edn. 1994, Yale University Press Pelican History of Art, ISBN 0300062176

• Rowland, Benjamin, The Art and Architecture of India: Buddhist, Hindu, Jain, 1967 (3rd edn.), Pelican History of Art, Penguin, ISBN 0140561021

• Shimada, Akira, Early Buddhist Architecture in Context:The Great Stūpa at Amarāvatī (Ca. 300 BCE-300 CE), Leiden: Brill, 2013, ISBN 9004233261, doi:10.1163/9789004233263