The Production and Reproduction of a Monument: The Many Lives of the Sanchi Stupa

by Tapati Guha-Thakurta

April, 2010

Email: [email protected] Centre for Studies in Social Sciences. Calcutta South Asian Studies, Vol. 29, No. 1, 77-109, http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02666030.2013.772801

-- The Bhilsa Topes; or, Buddhist Monuments of Central India: Comprising A Brief Historical Sketch of the Rise, Progress, and Decline of Buddhism; With an Account of the Opening and Examination of the Various Groups of Topes Around Bhilsa, by Brev.-Major Alexander Cunningham, Bengal Engineers, 1854

Picturesque Illustrations: Ancient Architecture Hindostan, by James Fergusson, Esq., F.R.A.S., &c., Author of Illustrations of the Rock-Cut Temples of India, and of An Essay on the Ancient Topography of Jerusalem, 1848

Tree & Serpent Worship, or Illustrations of Mythology and Art in India, From the Topes at Sanchi and Amravati, by James Fergusson, F.R.S., 1868

This essay considers the many lives of the ancient Buddhist stupa complex at Sanchi, tracing its transformations from a disused ruin and a site of ravage and pilferage to one of the best-preserved standing stupa complexes of antiquity. It engages with nineteenth-century histories of Sanchi's passage from discovered and excavated relic to portable object and image, exploring some of the processes of its imaging, replication, display, and documentation that preceded and paralleled the intense spurt of photography at the site, highlighting the tightening institutional grip of the colonial state and the intensification of the practices of archaeological repair, conservation, and care, culminating in the ‘Marshall era’. Contending claims for control and custody attended the politics of the possession and resacralization of the site, intensifying the vortex of secular and sacred, archaeological and devotional consecrations that accompanied Sanchi's transition from a colonial to a national monument. In conclusion, Sanchi's travels and afterlives are explored as a secular architectural form and consecrated religious monument, within and outside the nation, in postcolonial and contemporary times.

Situated on the small hillock of Sanchi amidst the Vindhya mountain range, 46 kilometres from the state capital of Bhopal in the Slate of Madhya Pradesh, is a cluster of structures of an ancient Buddhist stupa complex dating from the third century BCE. The guidebook of the Archaeological Survey of India presents Sanchi as unique in 'having the most perfect and well-preserved stupas anywhere in India'.1 The consecration of this stupa complex under the Mauryan emperor Asoka harks back to the years of the institutional foundations of Buddhism, when the building of such structures and the geographical distribution of these sacred relics across the empire and Sri Lanka played a crucial role in the state-sponsored propagation of the faith.2 The monumental function of these structures can be well dated back to these ancient times. But if we were to take a different modern notion of the 'monument', then it is in colonial India, in the course of the late nineteenth and early twentieth century, that we witness a new monumental metamorphosis of this ancient Buddhist site. The birth of the monument is then tied up with a distinctly imperial history of the remaking of the ancient pasts of modern India.

The transformation of Sanchi from a disused ruin and a site of ravage and pilferage to one of the best-preserved standing stupa complexes of antiquity was the proud achievement of the Director-General of Indian archaeology, Sir John Hubert Marshall (Figures 1, 2). It was in the course of Marshall's operations, from 1912 to 1918, that the complex took on much of its current-day appearance -- when, to quote Marshall, 'one and all the monuments [were put] into as thorough and lasting state of repair as possible', and one of the country's earliest site museums was set up at Sanchi, where all the 'movable antiquities' (sculptures, architectural fragments, and inscriptions) from the site were collected, arranged, and catalogued.) Sanchi occupies a central place in the triumphalist claims of colonial Indian archaeology, which could boast of its own 'Marshall era': a time of spectacular reconstructions of the country's decaying archaeological sites.4

1. 'Sanchi, General View south of the Topes, 1913-1914'. Photograph from the John Marshall album. Courtesy of Alkazi Collection of Photography, New Delhi.

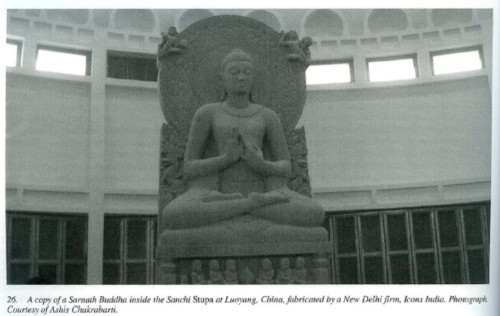

This essay looks back from the vantage point of the celebrated 'Marshall era' to a series of earlier moments that mark out the colonial biography of Sanchi. These moments, I argue, reveal a far more fractured encounter with modernity and a more muddled history in the transition of the site from ruin to monument than there is room for in the standard narratives of the authoritative remaking of the ancient site by the institutions and expertise of modern archaeology.5 The first section of the essay engages with these nineteenth-century histories of Sanchi's passage from discovered and excavated relic to portable object and image, exploring some of the processes of imaging, replication, display and documentation that preceded and paralleled the intense spurt of photography at the site. My idea of the 'many lives' of this monumental complex is built around its off-site careers as object and image in different exhibitions, museums, and scholarly compendia. These, in turn, contributed to a growing monumentalization of the structures on site under the tightening institutional grip of the colonial state and the intensification of the practices of archaeological repair, conservation, and care, culminating in the 'Marshall era.' The next section briefly revisits the history of the site in this era to critically open up some of the implications of Marshall's archaeological project by considering other claimants for control and custody and other players in the politics of the possession and resacralization of the site in the same and subsequent decades. In doing so, I wish to underline the competing semantic layers in the restitution of the 'true' pasts of Sanchi, and the new vortex of secular and sacred, archaeological and devotional consecrations that attended its transition from a colonial to a national monument. In the final section I touch on some of Sanchi's travels and afterlives, as a secular architectural form and consecrated religious monument, within and outside the nation, in postcolonial and contemporary times. From the middle years of the nineteenth century into the present, we see the aura of the in situ monument continuously refracted by its portability and reproducibility as form, image, and copy in changing locations to serve different commemorative functions.

The ravage of discovery

'The main injury to Sanchi', it is now widely argued, 'was caused by the vandalism of modern excavators'.6 Highlighted with increasing intensity in all later histories of Sanchi, this point of view is ingrained even in the successive accounts of nineteenth-century British surveyors of the site. What it highlights is the general nature of early colonial archaeological explorations, where 'collateral damage' appeared to be an inevitable fallout of the imperatives of antiquarian curiosity and collecting where narratives of native disinterest and misuse of ancient stones could nonetheless be effectively invoked to offset the correctness and the legitimacy of the white man's intrusions. On many counts, the stupa complex at Sanchi was far more fortunate than its period counterparts at Bharhut in the Nagod district of the Central Provinces and at Amaravati in the Guntur district of the Madras Presidency. It did not suffer the kind of large-scale removal of its sculpted stones and railing pillars, as much by the local populace as by colonial officials, which, in the other cases, rendered impossible the preservation of the remains on-site and made for their reassembled, reconstructed existence within the museums of the empire.7 At Sanchi, what the first British explorers initially encountered were two remarkably well-preserved stupas, one large and the other smaller, alongside an intact outer railing and three still-erect elaborately sculpted gateways around the main edifice.8

2. View of the Great Stupa, after the restoration of the berm railing. 1918-19 Sanchi. Silver gelatin print, reproduced in the Annual Report of the Director General of Archaeology for the year 1918-19 Plate VII. Courtesy of Alkazi Collectino of Photography. New Delhi.

In 1819, Captain Edward Fell of the 10th Native Infantry -- one of the period's growing breed of army officials-turned-Orientalist scholars, to whom is attributed the first modern-day account of Sanchi -- described with awe the size and sturdiness of the great hemispherical dome, 'to all appearance solid', its outer mortar coating still in 'perfect preservation' except in one or two places where it had been washed away by rain.9 Ironically, it was the very existence of such a preserved dome that now exposed the Great Stupa and its smaller pair to the new archaeological assault of being 'opened up'. Opening up these 'topes' (as they were called), by driving a shaft through the top towards the centre of the hemisphere to reach the inner chambers and ferret out the reliquary sacred caskets, would become the specialized pastime of travelling antiquarians in British India. By the middle years of the nineteenth century it had emerged as a particular forte of the pioneering field-archaeologist Alexander Cunningham,10 who had first performed this operation at the Dhamek stupa at Sarnath in 1834, and then, it is said, with greater effect at the main stupa at Sanchi, during his intensive exploration of the site with Lt. Col. F. C. Maisey in the early months of 1851. What seems to have been at issue within the early annals of archaeology in India was less the 'correctness' of such a venture than the expertise and care with which it could be carried out.

What Captain Fell had stopped short of executing (despite his great curiosity and speculation about the internal construction of this massive stone mound) was undertaken a few years later, in 1822, by another amateur explorer, T. H. Maddock, the political agent of the princely state of Bhopal, along with his assistant Captain Johnson. As commented in all accounts, it was the distinctly inexpert nature of Maddock and Johnson's operations -- whereby they drove shafts into the body of the stupa from the top and the sides, without succeeding in reaching the centre -- which led to large structural breaches in the brick-work and half-destroyed the domes that Captain Fell had seen standing in 'perfect repair' only a few years earlier.11 Three decades later, the claimed scientificity and success of Alexander Cunningham's renewed opening of the Sanchi stupas has also remained a matter of contention within the archaeological discipline and its historians.12

At the time, the end results, it seems, amply justified the operations. By penetrating the hidden depths of the mounds and retrieving from within the glazed-black inscribed reliquary caskets, Cunningham was able to identify the names of several Buddhist monks whose remains were buried within the cluster of stupas in this Bhilsa region, establishing the existence at the site of the funerary relics of two of Buddha's foremost disciples, Sariputra and Mahamogalana.

Now I'll come to the main point, context and significance of the Library of Congress scroll. What's it about? Well, I call it the "Many Buddhas Sutra." I would describe it as a combined comparative biographical summary of the lives of 15 Buddhas beginning with Dipankara, who lived many billions of years ago, and ending with Sakyamuni or Siddharta or "our Buddha" as he's sometimes called. And then going on one more to Maitreya or Ajita who is the next Buddha. So those 14 Buddhas in the past and one Buddha in the future. So these are the 15 Buddhas involved. Start with Dipankara. Number 14 is Sakyamuni who actually is Sakyamuni the second, surprisingly. And then on to Maitreya in the future...

There's another related text which contains these lists of buddhas and their times and their characteristics. It's called the Bhadrakalpikasutra. Some of you might be familiar with it. And Bhadrakalpika means it talks about the bhadrakalpa, kalpa means eon. And it's a list of buddhas but not from the past but looking ahead in the future. So it actually starts with the first Buddha in the bhadrakalpa that is Kakusandha and goes through Sakyamuni, our Buddha, and Maitreya and then 996 more buddhas are still to come within this Bhadra era. ... So at this point, you might be wondering the text that I'm primarily concerned with contains 15 buddhas. I mentioned another one that enumerates 1001 buddhas and there are many other numbers. There's a famous early sutra, the [inaudible] sutra, which has seven buddhas which seems to be the original number. There's another polytext called Buddhavamsa which lists 25 buddhas. And significantly in that case, it lists 25 buddhas but it begins with Dipankara and that's particularly an important moment within the history of the buddhas plural, Dipankara has a special importance which I will explain in a few minutes. Just I'll mention one other number, the Mahavastu which is a Sanskrit biography of the Buddha, also has a list of buddhas. It has a long list, 331,140,263 buddhas from the remote inconceivable past down to the present time of Sakyamuni...

So how many buddhas are there? I finally come back to the question. Infinite number. Why infinite? Because time is infinite in the Buddhas conception both in the past and the future. There is no beginning. There is no end. And throughout history, buddhas are either present or most of the time in the process of forming at some time. And that's why the Mahavastu can say in all seriousness that there are 331 million et cetera buddhas. There're actually much more than that. There are an infinite number. But these different texts or these different presentations, usually by the Buddha himself, simply address the issue or explain the issue in a limited scope because you can't, well the Buddha can talk about, understand eternity but we can't. So it takes -- These different texts are really slices of history, slices of Buddha history, which is infinite from beginning to end. Some of them talk about the recent past. Some of them talk about a little farther in the past. Some go into the future. Some are concerned mainly with the future. But they're all just pieces of the big picture. I call them slices of history...

In the list of 15, there's Sakyamuni the first and of course it doesn't say the first. I just put together those numbers. He was number eight. I don't know. I'm not sure. And then Sakyamuni the second. But there's another point about that which I didn't mention. I talked about that list in the Mahavastu of 331,140,263 buddhas. What I didn't say is that out of the 300 million, out of the 331, 300 million were named Sakyamuni. And according to that text, there was a stretch of 30 million buddhas in a row that were all had the same name. And I have thought about and failed to understand what that, why that is and what that means. But there is -- You know, buddhas are and by impression, they're more or less the same and their images, I don't think I have one here, but you see in Gandhari and other sculptures, you see sets of buddhas like the seven buddhas or sometimes eight buddhas and they're all almost exactly the same. So there seems to be a range of possibilities that buddhas are always similar and they can be very similar and sometimes they are absolutely identical.

-- One Buddha, 15 Buddhas, 1,000 Buddhas, by Richard Salomon

On 2 February 1898 — that is to say, when Fuhrer was still deeply entrenched in his main dig at Sagarwa — the Government of Burma wrote to the Government of the NWP&O concerning complaints it had received from a monk named U Ma. These involved a certain Dr. A. A. Fuhrer, Archaeological Surveyor to the Government of the NWP&O. Shin U Ma had first taken the complaints to a local government official in Burma, Brian Houghton, and had then backed them up with tangible evidence in the form of letters received from Dr. Fuhrer. Houghton had duly passed U Ma's complaints and copies of his letters on to government headquarters in Rangoon, as a consequence of which they arrived on the desk of the Chief Secretary to the Government of the NWP&O, who passed them on to the Secretary of the Department of Revenue and Agriculture, Archaeology and Epigraphy. From there they made their way to the desk of the Commissioner of Lucknow.

As soon as he returned to his offices at the Lucknow Museum in early March Fuhrer was confronted with the communication from Burma and asked to explain himself. According to the file, his letters to the Burmese monk went back as far as September 1896, when he had written to U Ma about some Buddhist relics he had sent him, allegedly obtained from Sravasti. The contents of this first letter indicate that the two had met while the Burmese was on a pilgrimage to the holy sites in India and had struck up a friendship not unlike that described by Rudyard Kipling in his novel Kim (then in the process of being written in England), which begins with a wandering Tibetan lama being greatly moved by the knowledge of Buddhism shown by the Curator of the Lahore Museum (Rudyard's father J. L. Kipling).

Dr. Fuhrer and U Ma had then come to some arrangement for the one to send the other further relics. On 19 November 1896 Fuhrer wrote again to U Ma to say that:The relics of Tathagata [Sakyamuni Buddha] sent off yesterday were found in the stupa erected by the Sakyas at Kapilavatthu over the corporeal relics (saririka-dhatus) of the Lord. These relics were found by me during an excavation of 1886, and are placed in the same relic caskets of soapstone in which they were found. The four votive tablets of Buddha surrounded the relic casket. The ancient inscription found on the spot with the relics will follow, as I wish to prepare a transcript and translation of the same for you.

This letter of 19 November 1896 was written more than a year after Fuhrer's first trip into Nepal made in March 1895 (during which he made his discovery of the Asokan inscription on the stump at Nigliva Sagar), but just before he set out on his second foray into Nepal (where he would meet up with General Khadga Shumsher Rana at Paderiya on 1 December 1896). Yet already, it seems, he had found Kapilavastu. In the year referred to in his letter — 1886 — he was still a relative newcomer to the NWP&O Archaeological Department and had yet to conduct his first excavation.

Fuhrer's next letter to U Ma was dated 6 March 1897, three months after his much trumpeted Lumbini and Kapilavastu discoveries. In it he referred to more Buddha relics in his keeping which he would hold on to until U Ma returned to India. Seven weeks later, on 23 June, there was a first reference to a 'tooth relic of Lord Buddha', and five weeks on, on 28 August, a further reference to 'a real and authentic tooth relic of the Buddha Bhagavat [Teacher, thus Sakyamuni]' that he was about to post to U Ma.

The letters now began to come thick and fast. On 21 September Dr. Fuhrer despatched 'a molar tooth of Lord Buddha Gaudama Sakyamuni ... found by me in a stupa erected at Kapilavatthu, where King Suddhodana lived. That it is genuine there can be no doubt.' The tooth was followed on 30 September by an Asokan inscription Fuhrer claimed to have found at Sravasti. Then on 13 December Fuhrer wrote to say that he was now encamped at Kapilavastu, in the Nepal Tarai, where he had uncovered 'three relic caskets with dhatus [body relics] of the Lord Buddha Sakyamuni, adding that he would send these relics to U Ma at the end of March. What is most odd here is that on 13 December 1897 Fuhrer had not yet entered the Nepal Tarai, having been given strict instructions that he was not to do so until 20 December.

This bizarre hoaxing — for no element of financial fraud seems to have been involved — could not go on. The arrival in Burma of the Buddha's molar tooth seems to have been too much for the hitherto credulous Burmese monk, who soon afterwards wrote what sounds like a very angry letter protesting at the remarkable size of the tooth in question. This letter was evidently forwarded from Lucknow to Basti and then probably carried by mail runner to Fuhrer's 'Camp Kapilavastu' at Sagarwa. It was replied to on 16 February 1898, when the Archaeological Surveyor was still encamped at Sagarwa. Writing at some length, Fuhrer went to great pains to mollify the Burmese, declaring that he could quite understand why 'the Buddhadanta [Buddha relic] that I sent you a short while ago is looked upon with suspicion by non-Buddhists, as it is quite different from any ordinary human tooth' — as indeed it was, since it was most probably a horse's tooth — 'But you will know that Bhagavat Buddha was no ordinary being, as he was 18 cubits in height [27' @ 18"/cubit; 48' @ 32"/cubit] as your sacred writings state. His teeth would therefore not have been shaped like others: In a further bid to shore up the credibility of the tooth, Fuhrer went on to say that he would send U Ma —an ancient inscription that was found by me along with the tooth. It says, 'This sacred tooth relic of Lord Buddha is the gift of Upagupta.' As you know, Upagupta was the teacher of Asoka, the great Buddhist emperor of India. In Asoka's time, about 250 BC, this identical tooth was believed to be a relic of the Buddha Sakyamuni. My own opinion is that the tooth in question is a genuine relic of Buddha.

This supposed Asokan inscription was afterwards found to be written in perfectly accurate Brahmi Prakrit, its most obvious models being the many similar relic inscriptions found at Sanchi and other Buddhist sites, with which Fuhrer was very familiar through his work on Epigraphia Indica.

-- The Buddha and Dr. Fuhrer: An Archaeological Scandal, by Charles Allen

************

Emboldened by the success of this 'opening' and the rich historical data it yielded, and driven by his zeal to uncover India's ancient Buddhist past, Cunningham, in his book, The Bhilsa Topes (1854), impressed upon the Court of Directors of the Company the need for 'the employment of a competent officer to open the numerous Topes which still exist in North and South Babar, and to draw up a report on all the Buddhist remains of Kapila and Kusinagara, of Vaishali and Rajagriha, which were the principal scenes of Sakya's labours'.13

Such a statement would serve as one of the founding directives behind the setting up of the country's first Archaeological Survey in 1861 under the direction of Cunningham, paving the way for the increasing priority of material remains over textual records as 'sources' for India's lost histories. And it is broadly this narrative of excavations and discoveries that has continued to prevail in the story of the progressive unfolding of archaeology in colonial India, even as later officials and scholars have berated Cunningham for failing to repair the structural breaches he made on the body of the stupas, and for his personal aggrandisement and careless dispersal of many of the 'treasures' he had extracted from them. These continuous arrogations of credit and blame, during different periods of explorations and conservation, come to us now as an integral part of the archaeological making and remaking of monuments in British India.

The production of images

If throughout this period the urge to dig, break open, and collect was a driving force, so too was the will to visually preserve what was seen and unearthed. The act of copying would become a primary way of arresting decay, countering damage, and documenting structures for posterity.14 Sanchi in the early and mid-nineteenth century offers itself as one such key site of imaging and copying, even as its monuments suffered some of the most obvious effects of 'destruction through excavation'.15 Captain Fell's report of 1819 provides one of the earliest samples of an ethnographic scrutiny of Sanchi's famous legacy of the gateway sculptures -- descriptions and measurements of all the various human and animal types who adorned the lintels, pillars, and cornices, along with the details of postures, gestures, drapery, head-dress, and scenes of ritual ceremonies and worship. Lamenting his 'want of sufficient ability in the art of drawing to do justice to the highly finished style of the sculptures', the only image that accompanied his article was a crude 'native drawing' of a sculpted panel depicting the worship of a stupa by tiered rows of figures (Figure 3).16

3. Sculpted frieze, Sanchi. Engraved drawing, reproduced in the Journal of the Asiatic Society of Bengal, 3 (1834), Plate XXVII.

4. Frederick Charles Maisey: Rear view of the full standing structure of the northern gateway. Sanchi. Coloured lithograph from F. C Maisey. Sanchi and its Remains (London: Keagan Paul, Trench. Trubner & Co., 1892), Plate IV.

4. Frederick Charles Maisey: Sculpted panel with ladder signifying Buddha's descent from heaven, Sanchi. Coloured lithograph from F. C Maisey. Sanchi and its Remains (London: Keagan Paul, Trench. Trubner & Co., 1892), Plate IX.

The mid-century brought with it a spurt of textual description and documentation of the site, first in an account by J. D. Cunningham, an army engineer who was then Political Agent in the Bhopal Durbar, and then in the publication in 1854 of the book, The Bhilsa Topes, by his famous brother Alexander Cunningham. For all the damage that his excavations entailed, Cunningham, it is acknowledged, did an exemplary service in documenting his finds in this first of his scholarly monographs, providing 'the first systematic exposition of the character, sculpture, and inscriptional wealth of the stupas.'17 Side by side with Cunningham's textual labours appeared twenty-three finely-engraved line drawings, which move between the diagrammatic and pictorial -- taking us from the lay-out of the site and architectural elevations of the structures to representations of the sculpted figures and scenes of the gateways, all the principal relic caskets, and the different symbols of the Buddhist faith that were to be found in the Sanchi sculptures.18

5. James Fergusson, 'Ruins of the Black Pagoda of Konarak'. Lithograph prepared by T. C. Dibdin from his on-site sketch. From Fergusson, Picturesque Illustrations of Ancient Architecture in Hindostan (London: J. Hogarth, 1848).

More than Cunningham, it was his assistant, Lieutenant Frederick Charles Maisey, who carried the main onus of visual documentation during their extensive survey of the site in 1851. Acting on a deputation from the Company's Court of Directors, Maisey's attention was focused on the gateway 'bas reliefs', which he laboriously recorded through drawing, copying entire gateways, pillars, and balustrades alongside individual sculpted panels. Four decades later, in 1892, Maisey's drawing of the sculptures would appear as tinted lithographs in a book containing a full description of all 'the ancient buildings, sculptures, and inscriptions at Sanchi'. Much of the documentary worth of this book, however, would be overshadowed by the author's controversial argument about the evidence he had garnered on 'the comparatively modern date of the Buddhism of Gotama or Sakya Muni'.19 In a period that saw a large outpouring of European scholarship on Buddhism in ancient India, Maisey's views were quickly dismissed as ill-founded -- motivated, as Cunningham pointed out, only by 'the pious wish to prove that Christianity was prior to Buddhism', even as Cunningham acknowledged the author's intimate acquaintance with the Sanchi stupas and recommended the numerous plates of the book 'as they give very faithful copies of the sculptures on a large scale' (Figures 4a, 4b).20 These images wrought by Maisey stand as the first in a long line of the visual imaging of the gateway sculptures of Sanchi, presaging their modern life as the most photographed objects of ancient Indian art.

From the late eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century -- from travelling artists like William Hodges or the Daniells to antiquarians and collectors like Richard Gough and Colin Mackenzie down to the architectural scholar James Fergusson -- a growing premium was placed on the site drawing of ancient monuments that could then be embellished and developed into a coloured engraving or lithograph (Figure 5). In an age of rapidly changing printing technologies, engraving and lithographs opened up a range of reproductive possibilities, feeding into the production of the first photographic images of ancient structures. One of the gateways of Sanchi found its way as one such finely-wrought lithographed image into the head of Fergusson's early work, Picturesque Illustrations of Ancient Architecture of Hindostan (1848), to mark the antiquity and grand beginnings of Indian architecture (Figure 6). It was the only monument in the book that Fergusson had not seen and drawn first-hand, but he vouched for the correctness of the image by comparing it with Colin Mackenzie's drawing of the structure in the course of the latter's extensive survey and documentation.21 Already by the mid-nineteenth century, the Mackenzie drawings gathered in the India Museum in London were serving as an off-location archive of images on Indian antiquities for scholars in London. In the 1860s, the Maisey drawings of the Sanchi sculptures, which by then had travelled to London to be stored in the library of the India Office, would fulfil a similar and even larger need for Fergusson.

6. A Sanchi gateway. Lithographed drawing. Used as frontispiece, first in Fergusson, Picturesque Illustrations of Ancient Architecture in Hindostan, and later in Fergusson, Tree and Serpent Worship (London: India Museum, W. H. Allen, 1868).

7. Frederick Charles Maisey. Sculpted panel showing Queen Maya's dream, Prince Siddhartha's departure from Kapilvastu, and worship at the Bodhi tree, Sanchi. Lithograph of drawing, used in Fergusson, Tree and Serpent Worship, Plate XXXIII.

It was in a display and a publication spearheaded by Fergusson that the monuments of Sanchi would embark on a new global career as images. The occasion was the Paris International Exhibition of 1867, for which Fergusson was working on presenting a display of photographs and plaster casts of Indian architecture and sculpture. This is when, in the course of his search for ideal architectural specimens in the collections of the India Museum at Fife House in London, he came upon a large hoard of limestone sculptures from the stupa site of Amaravati, which had been lying abandoned for years then, first in the dockyards, then in the rear coach houses of Fife House, ever since their shipment to London in the mid-1850s.22 It is ironic to juxtapose this notorious history of the dispersal and neglect of the Amaravati 'marbles' in Madras and in London with the careful storage in the same years of the drawings of Mackenzie and Maisey in the India Museum and the India Office. The visual record had a need and a status that had, at times, even transcended the fate of the original. This anomaly was now fast resolved -- even as the potentials of the new technology of photography were mobilised in the process of the institutional reclaiming of the Amaravati sculptures. Between Sanchi and Amaravati, we see one of the earliest on- and off-site deployments of photography in the staging of archaeological scholarship and museum displays. While the photographer Linnaeus Tripe was commissioned to photograph the sculptural panels of Amaravati in the Madras Museum in 1858,23 in the winter of 1866-67 Fergusson undertook the services of W. Griggs, the photographer attached to the India Museum, to have a complete set of photographs made on the same scale as the panels as an aid for the reassembling of the fragments in the museum. These enlarged photographs and lithographed drawings of Amaravati, alongside a few select specimens of the original 'marbles', found pride of place in Fergusson's display of Indian architecture at the Paris exhibition, and occasioned the publication of an entire volume on these sculptures.24

James Waterhouse, Northern Gateway of the Great Stupa at Sanchi. Used in Fergusson, Tree and Serpent Worship. Courtesy of the British Library, London.

Fergusson's discovery at the same time of the album of Maisey drawings in the India Office and his acquisition of a set of photographs of Sanchi taken by Lieutenant Waterhouse, R. A. (to date, the earliest photographs of the site), would also ensure for Sanchi a place in the same display and volume. Identified as the older of the two 'Topes', Sanchi would now be placed prior to Amaravati in the line of antiquity and the chain of excellence of India's early Buddhist art.25 That Fergusson's richly-illustrated volume on the Sanchi and the Amaravati sculptures carried the title Tree and Serpent Worship, and that it contained a large section tracing such rituals of worship though the ancient Western European and East Asian cultures down to India, to eventually hone in on the specific representations of such symbols and scenes in the Sanchi and Amaravati sculptures, has rendered this work something of an oddity in Indian art-historical scholarship.

© Jean-Pierre Dalbéra - Depiction of Akhenaten and his family

Plate L. Elevation of the external faces of two pillars of outer enclosure, Amravati. Tree & Serpent Worship, or Illustrations of Mythology and Art in India, From the Topes at Sanchi and Amravati, by James Fergusson, F.R.S., 1868

In its time, however, it augured a widespread mode of reading sculptures as evidence for a racial and ethnological history of ancient India, drawing from them clues to the appearance, dress, customs, and faith of the people of the period. And it was precisely to aid such modes of reading that the details and accuracy of the imaging of the sculptures became crucial in the volume, with Maisey's lithographed drawings of the sculptures and Waterhouse's photographs of the structures brought together to closely supplement each other's functions[/i] (Figures 7, 8).26[/b]

Fergusson's display on Indian architecture at the Paris exhibition and the subsequent publication of his Tree and Serpent Worship coincided with the presentation in 1869 of an elaborate Report on the Illustration of the Archaic Architecture of Hindostan, by J. Forbes Watson, the Director of the India Museum in London.27 The report elaborated on the suitability of particular objects for one type of illustration as against another. While photography was singled out as the most complete form of documentation, coloured drawings were seen to be essential for capturing the fine details of tile, mosaic, and inlaid decoration, while moulds and casts were seen as best for marking the different styles of architectural ornament. The key concerns were with truth and precision, the detail and the whole. Each illustration was to stand as a source of complete and accurate knowledge on the represented object, and each was to be linked with the other within a historical sequence and series.28 The end product was to be an ordered and classified visual archive -- the kind of panoptic archive that had become germane to the modern discipline of art history.29

From his distant base in England, Fergusson had a special investment in the rigour and thoroughness of this illustrative project -- in the availability of a comprehensive photographic archive on India's monumental heritage which he could rely on as his prime resource in the processing of a pan-Indian history. Already by the 1860s he claimed to have amassed over five hundred photographs of India's architectural sites, selections from which he placed on display at the Paris International Exposition.30 The Art Library of the South Kensington Museum also seemed to have had a similar stock of photographs, from which two hundred were exhibited at the Society of Arts on the occasion of Fergusson's lecture on the Study of Indian Architecture.31 It is from this collection that he published in 1869 the first handy compendium of fifteen photographs as Illustration of Various Styles of Indian Architecture, once again featuring a photograph of a Sanchi gateway as the inaugural point of this history.32

Travels of the gateway

The same years saw a far more spectacular encounter of British museum-goers with the Sanchi monument. In the summer of 1870, a full-size plaster cast model of the eastern gateway of the Great Stupa arrived in the Liverpool docks, for display in the South Kensington Museum. The monumentality of this cast would play a significant role in the designing of the special Architectural Courts of the museum in the early 1870s. In a photograph of 1872 we see the gateway installed amidst other architectural facades from India, 33 feet high, looming towards the sky-light of the arched ceiling, dwarfing the other cast of a corbelled pillar from the Diwani-i-Khas building of Fatehpur Sikri (Figure 9). These Architectural Courts, with their plaster casts of great works of architecture and art from across the world, were meant to overwhelm the visitor with the sheer physical size of the exhibits, and the technical prowess that had gone into their making. The Sanchi gateway stood here as the grandest symbol of the distant Indian empire, of imperial custodianship of India's ancient architectural heritage, rivalling in its antiquity and artistry the casts of famous Western objects like the Trajan column from Imperial Rome or Michelangelo's David from Renaissance Florence in the adjoining courts.33

9. Plaster cast of the Eastern Gateway of the Sanchi Stupa in the Architectural Court of the South Kensington Museum, London, c. 1872-73. Albumen print. Courtesy of The Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), Montreal. Reproduced from Pelizzari, Traces of India: Photography. Architecture and the Politics of Representation (Montreal: CCA, 2003).

The formation of these grand Architectural Courts at South Kensington had been facilitated by a pan-European imperial monarchical convention, signed during the Paris International Exhibition of 1867, in which fifteen reigning princes agreed to promote the reproduction (through casts, electrotypes, and photographs) of art and architectural works from all over the world for museums in Europe. The knowledge of such monuments, it was believed, was 'essential to the progress of art', and with the advance in reproductive technologies that cause could now be fulfilled in Europe 'without the slightest damage to the originals'.34 The colony in India offered a wealth of ancient artistic traditions for the elucidation of the West, with the Sanchi gateway now proclaiming as much the antiquity of that tradition as the magnitude of the empire that had taken charge of its discovery and dissemination. The prestige of this particular architectural cast at South Kensington in that period is borne out by the commissioning of several replicas of this piece for transportation to museums in Edinburgh, Paris, and Berlin, and display at the London International Exhibition of 1871.

It was a matter of immense good fortune for the site that what came to travel was only this marvel of a physical replica and not the original gateways. For, in the prior decades, some of the empire's archaeologists and officials had seriously pushed for the removal to London of two of the actual gateways (the ones still fully standing and in near perfect condition) in the prime interests of their safekeeping. Concerned about the rampant pilferage and dispersal of excavated treasures from sites, Cunningham during his excavation at Sanchi in 1851 appealed to the Court of Directors to arrange for proper vigilance for all the antiquities on site. At the same time, he also unhesitatingly recommended the transportation of the two still-standing northern and eastern gateways of the Great Stupa to the British Museum, 'where they would form the most striking objects in a Hall of Indian Antiquities'. The value and appeal of these sculpted gateways in London, he believed, would be greatly enhanced by the account contained of them in his book, while 'their removal to England would ensure the preservation and availability for study to future scholars.'35 In 1853 H. M. Durand, political agent at the Bhopal Durbar, narrowed the proposal to the removal of one rather than two of the two standing gateways, with the suggestion that Sikander Begum, ruler of Bhopal, be persuaded to make this offer of the grandest of archaeological 'gifts' to Queen Victoria. What stalled the offer was the unavailability of the kind of expertise needed for the dismantling and shipment of so many tonnes of stone without destroying the structure and its carvings. Even in this inglorious act of robbing Sanchi of one of her gateways, the Court of Directors paradoxically held high the need for utmost care in this process of removal to prevent any further damage to the structure and to the main stupa. By the time arrangements were complete to conduct the job with the requisite care, the rebellions of 1857 intervened, giving the gateway a fresh lease of life on site.36

Ten years later, the proposal for the travel abroad of the same eastern gateway came up again -- this time as a request that came from the French Consul General in India for the 'gift' of the gateway to Emperor Napoleon III, who wished to have it installed at the Paris International Exhibition of 1867. The Begum of Bhopal, however, felt that the British Museum had the first claims to the structure, if it was to travel at all. That the Begum's renewed offer was now turned down by the colonial authorities, most forcefully by the viceroy himself, was a clear sign of the period's growing emphasis on in situ conservation of monuments and its mounting programmes for the preparation of plaster casts, drawings, and photographs of objects for museum collections. 'It would be an act of vandalism', it was declared, 'little creditable to the British government, to let the gateway go either to London or Paris'.37 So the eastern gateway stayed where it was, with elaborate plans afoot for constructing its exact three-dimensional replica for display at the South Kensington Architectural Courts.

10. Charles Shepherd. Casting operations in process, under the supervision of H. H. Cole, at the Quwwat-ul-Islam mosque complex, Delhi, c. 1870. Albumen print. Courtesy of The Canadian Centre for Architecture (CCA), Montreal. Reproduced from Pelizzari, Traces of India.

The details of the official correspondence concerning this mammoth casting operation at Sanchi bear ample testimony to the urgency and importance attached to it.38 An entire cargo containing 28 tonnes of plaster of paris and gelatine was carried by the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company from London to Calcutta, along with eighty-eight special boxes lined in tin, so that the casts could be retained in them for transportation to England. The material was then carried across by bullock cart to the site for the execution of the casts. Although the plan was to produce three separate casts of the structure (for museums in London, Paris, and Berlin), it was found eventually to be more time and cost effective to produce one perfect cast in around fifty small parts, a job that itself took four months to complete, between December 1869 and March 1870. What was called the 'parent cast' was then packed, in all its parts, in the tins in which they were moulded, and shipped to England, where the pieces were laboriously assembled to recreate the standing edifice. And it was from this master replica that further copies were prepared at South Kensington for Paris and Berlin.39

Supervising the entire project was Lieutenant Henry Hardy Cole of the Royal Engineers. Son of Sir Henry Cole, Superintendent of the South Kensington Museum, trained in London in different techniques of plaster cast modelling, Cole was then functioning in India as a key agent in the procuring of drawings, photographs, and casts of Indian architecture for his father's museum. In the same year that he worked at Sanchi, he would also extend his modelling operations to the carved pillars of the Qutb mosque at Delhi and of the Ibadat Khana in the Diwan-i-Khas at Fatehpur Sikri.40 A rare photograph from the Qutb site vividly enacts such theatres of cast making, with Cole standing in command, directing the preparation of moulds by local workers (Figure 10). Even as he prepared the plaster cast at Sanchi, Cole also worked on a set of detailed drawings of the carvings of all the four gateways, which were lithographed and stored in the India Museum, and also had a full set of photographs made of the subjects of the gateway sculptures from the cast that was installed at South Kensington.41 In the imperial museum complex, drawings, casts, and photographs can be seen as forming a close-knit ensemble of ordered knowledge of Indian art and architecture.