Rachol Seminaryby Wikipedia

Accessed: 7/19/24

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rachol_SeminaryIt is interesting to examine why types of the local language of Goa (Marathi) were not prepared at this stage.

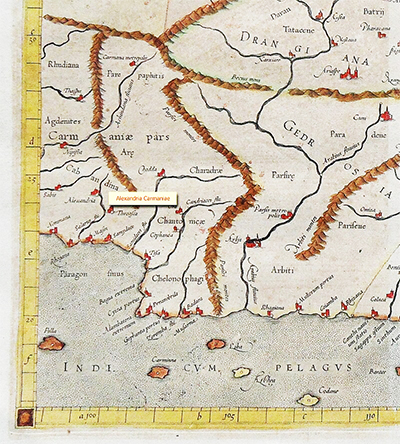

Fr. G. C. Rodeles writes that Gonsalves did actually think of preparing "Canarese" types, but did not pursue the idea on account of the clumsy shapes of the characters, the irregularity of pronunciation and the limited area in which the language was spoken. 31 [Rodeles, op. cit., p. 161.] In a recent article Fr. Schurhammer points out that Gonsalves had actually started preparing types of the Devanagarii script. He writes: —

"By the end of the year 1577 there were cast about 50 letters in the Devanagari script, but brother Joao Gonsalves who prepared them died in the following year, and his companion Fr. Joao de Faria also having expired in the year 1582, there was none who was able to undertake the work. For this reason the Puranna was printed in Latin characters in the College of Rachol in the years 1616 and 1649 and in the College of St. Paul in the year 1654." 32 [Georg Schurhammer, " Uma obra rarissima impressa em Goa no ano 1588," Boletim do Institute Vasco da Gama, No. 73-1956, p. 8.]...

Such information as is available about the literature known to have been printed in Goa during the 17th Century, is given below: —

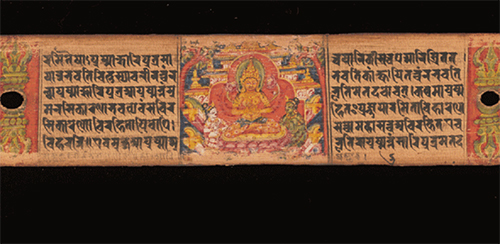

(i) 1616. Thomas Stephens. Discurso sobre a vinda de Jusu Christo Nosso Salvador ao Mundo (Discourse on the Coming of the Christ to the World). (No extant copy recorded).

This is the famous Purana by Fr. Stephens which is written in literary Marathi. The next two editions of this work were printed in 1649 and 1654. But none of these have survived to our day. The text of the fourth edition, printed in 1907 at Mangalore, 45 [Thomas Stephens, The Christian Puranna (Edited by J. L. Saldanha) Manglaore 1907.] was prepared from some manuscripts.

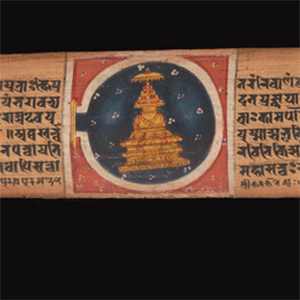

(ii) 1622. Thomas Stephens. Doutrina Christam.

This work on Christian Doctrine in the form of a dialogue is written in the dialect spoken by Goa Brahmins. This was written by the author before the Purana, but was published after the Purana.

A copy is available in the Government Library in Lisbon and another in the library of the Vatican in Rome. A facsimile edition prepared by Dr. Mariano Saldanha was published by the Portuguese Government in Lisbon in 1945.

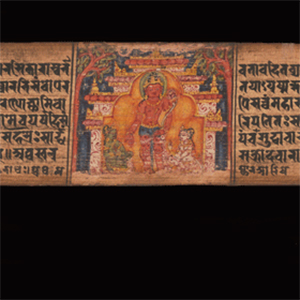

(iii) 1632. Diogo Ribeiro. Declaracam da Dovtrina Christam. (A statement of the Christian Doctrine) This was written in the Brahmin dialect of Goa. A copy is available in the Government library in Lisbon.

All the three works mentioned above were printed at the Rachol College. -- The Printing Press in India: It's Beginnings and Early Development Being a Quatercentenary Commemoration Study of the Advent of Printing in India (In 1556)

by Anant Kakba Priolkar, Director, Marathi Samshodhana Mandala, Bombay.

Rachol Seminary Façade of the seminary, 2005

Façade of the seminary, 2005Motto: Luceas sicut luminare

Type: Major Seminary

Established: 1609; 415 years ago

Rector: Rev. Fr. Donato Rodrigues

Students: 42

Location: Rachol, Goa, India

15°18′36″N 74°0′5″E

Campus: Urban

Website: racholseminarygoa.org

The Rachol Seminary, also known as Patriarchal Seminary of Rachol, is the diocesan major seminary of the Primatial Catholic Archdiocese of Goa and Daman in Rachol, Goa, India.

Historical outlineThe edifice that presently houses the seminary was

constructed by the Jesuits with donations from the boy-king of Portugal, Dom Sebastião, in the area occupied originally by a Muslim fortress.

The coat of arms of the King of Portugal at the entrance of the Seminary

The coat of arms of the King of Portugal at the entrance of the SeminaryThe foundation stone for the main quadrangular portion was blessed and laid on 1 November 1606 by Fr. Gaspar Soares. Three years later, on 31 October 1609, with the solemn celebration of the Vespers, the “College of All Saints” (Colégio de Todos os Santos) was blessed and inaugurated.[1]

Somewhere between 1622 and 1640, the name of the college was changed to "College of St. Ignatius" (Colégio de S. Inácio). The change was to pay homage to St. Ignatius of Loyola, the founder of the Jesuit Order, who had been canonized in 1622. The retable of the main altar of the Seminary Church testifies to this fact. The Seminary community still celebrates the feast of St. Ignatius, the titular of the Seminary Church, with a solemn high mass with Gregorian chant.

The Pipe organ on the choir loft of the Seminary Church

The Pipe organ on the choir loft of the Seminary ChurchThis festivity is preceded by a novena of preparation for the locals around and a week-long Retreat (Spiritual Exercises) for the seminarians. The Seminary also possesses a 19th-century Pipeorgan, that is played during liturgical services.

The Jesuits controlled the college for a century and a half. Having begun as a school for the training of natives, it gradually adopted the curriculum for training Jesuits and later even secular priests from 1646.

In 1759, the Prime Minister of Portugal, Marquis de Pombal expelled the Jesuits from Goa. Their institutions and properties were confiscated by the state and the college was shut down.[2] Three years later, in 1762, Archbishop-Primate Dom António Taveira da Neiva Brum e Silveira converted the abandoned College into the "Diocesan Seminary of the Good Shepherd" (Seminário do Bom Pastor) and placed it under the protection of the Infant Jesus. He entrusted to the native Oratorian Congregation of St. Philip Neri the work of priestly training. This was the first diocesan seminary erected in Asia, after the order passed by the Council of Trent (1563–1578) that all those desiring to dedicate themselves to the ecclesiastical ministry as diocesan (secular) clergy should pass through formation in a seminary. The retable of the altar of the internal Chapel of the seminary bears a picture of Jesus as the Good Shepherd. The Church, however, continued under the invocation of St. Ignatius of Loyola. In 1774, the ruling Royal Treasury Junta of Goa abruptly suppressed the seminary on the pretext that certain conditions were not being fulfilled, the real reason being economic.[3] In 1781, owing to a petition by the people of Salcete and the Municipality of Margao, the Court of Portugal ordered the seminary to be restored. The Municipality of Salcete financed the required repairs for the building. The college was thus reopened, and its management was entrusted to the Congregation of the Mission, popularly called Vincentians or Lazarists. At first, two Vincentian priests from the Convent of Rilhafolles, Portugal, were deputed at the instance of Queen Dona Maria I of Portugal. The seminary was also condecorated with the title of "Royal Seminary of Rachol" (Real Seminário de Rachol). Later, Vincentians from Italy also came to help in the administration of the seminary, bringing with them sacred relics and a vial containing the blood of a Roman saint and martyr, St. Constantius. These relics are preserved in the seminary Church even today. The seminary operated until 1790, when it was closed down for three years, after the Vincentians left the seminary. In 1793, the Oratorians were again deputed to run the diocesan seminary. They continued their work for about forty-two years.

Bad days dawned once again for the seminary, when in 1835 all religious institutes were extinguished in Portugal and in all its possessions. Consequently, the Seminary was run by the diocesan clergy[4] and came to be simply known as Seminário de Rachol.

In 1886, the Archbishop of Goa and Daman was bestowed the honorific title of Patriarch of the East Indies. Since then the seminary is known as the "Patriarchal Seminary of Rachol".

Curriculum of the seminaryThe curriculum of priestly formation began at a rudimentary level and gradually grew in subject matter. Archbishop-Primate Dom João Crisóstomo de Amorim Pessoa (1862–1874) and Archbishop-Patriarch Dom António Sebastião Valente (1882–1908) were the two Prelates who, in their own times, conducted an overhauling of the studies: Preparatory Course, Philosophy Course and Theology Course. Dom Valente made a few additions to the main edifice, such as a new wing with forty rooms, a library, a dormitory for the novices, an infirmary and a Chapel. This Prelate, who had the formation of seminarians very close to his heart, presented a new and updated Regulamento for the life in the seminary. The standard of studies in the seminary acquired such a height that Pope Leo XIII, acceding to Archbishop-Patriarch Valente's exposition and request, by his Apostolic letter Quum Venerabilis Frater, granted the Seminary the faculty of bestowing the academic degree of "Bachelor in Divinity". The requirements, as extant in the Apostolic Letter, were very strict. The Apostolic Letter, having obtained the royal pleasure (beneplacitum regium), was executed in Goa only in 1894. Since then up to 1931, when the faculty stood abolished by virtue of the Apostolic Constitution of Pope Pius XI Deus Scientiarum Dominus, thirty-five priests were conferred the said degree.

During the tenure of Archbishop-Primate Manuel de S. Galdino (1812–1831), an additional preparatory course was established at Mapusa (North of Goa). To accommodate increasing number of Theology students, Archbishop-Patriarch Valente built a two-storey new wing between 1890 and 1894. The first floor contained forty single rooms and a dormitory and study hall for beginners, while the second floor contained a library hall. Other students, called externos, were housed in rented cottages (comensalidades) under a Prefect of Discipline, from which they would commute to the Seminary for Mass and classes. With the setting up of the minor seminary of the Archdiocese at Saligão-Pilerne, from 1952 the additional Preparatory Course at Mapusa as well as the comensalidades at the Rachol Seminary ceased to exist. In 2002, a new Academic Block with some rooms, lecture halls and a spacious Auditorium over it was constructed.

At present the Seminary holds a three-year Philosophy Course, with concomitant graduation from the “Indira Gandhi National Open University”, Delhi (IGNOU). This is followed by a year of pastoral praxis in the parishes/institutions of the Archdiocese. The final phase is the four-year Theology Course. At the end of the Fourth Year of Theology, the students are ordained deacons. After further formation at the Pastoral Institute, and after exercising diaconal pastoral ministry in the parishes, they receive priestly ordination.

The Seminary of Rachol, with its motto LUCEAS SICUT LUMINARE, faithfully imparts holistic Catholic priestly formation to the aspiring candidates. Formation at the Seminary embraces the human, spiritual, academic and pastoral levels. Besides, there are several programmes organized on a regular basis in order to keep the young seminarians abreast with the realities of life and the needs of the Church. Institutions within the seminary, like the Literary and Cultural Association, the Catechetical Association, the Cell for Vocation Promotion, the St. Joseph's Outreach to aid the less fortunate, the Sports Association, etc. help the seminarians to put together their skills and cooperate with one another in various ventures. The choral society, established by Archbishop Valente, in 1897, known today as Coro de Santa Cecilia (Santa Cecilia Choir) provides the young students a rare opportunity to further their musical and choral talents for the glory of God.

The cloister (courtyard) of the Seminary

The cloister (courtyard) of the SeminaryThe seminarians are also shown how to love nature by active involvement in the agricultural activity of the seminary (paddy fields, vegetable gardens, fruit plants, flower gardens). Besides, the seminarians also visit prisons, slums, orphans, hospitals, senior citizens' homes, broken families and are involved in building Small Christian Communities in the vicinity of the parish of Rachol.

Multi-faceted serviceThis college has served the Church and humanity in varied ways. It was originally planned as a college for the education of the natives. It functioned as a Catechetical School for the training of catechumens, a hospital, an orphanage, a Primary School (in Portuguese), a Konkani School for the missionaries who came from Europe, a School of Catholic morality, before being finally erected into a seminary.

Since 1762, after the closure of the seminaries at Old Goa and Chorão Seminary, Rachol Seminary has produced many priests. Ecclesiastics have spread the Gospel to several parts of the world, including Mozambique, Angola, Cabo Verde, Kenya, Tanzania, Venezuela, Canada, Sri-Lanka, Pakistan, Burma, and Japan. Missionaries from this Seminary have also been pioneers in establishing various local Churches in the different states of India. Several students of Rachol have been elevated to the episcopate. The group of priests who got together in 1888 to form the well known Indian-born “Society of the Missionaries of St. Francis Xavier”(Pilar Fathers), as well as those priests who revived the Society in 1930, themselves studied at the Rachol Seminary.

Rachol Seminary also had the distinction of housing a printing press, the third one in Goa. It functioned for almost sixty years in the college in the 17th century. It brought forth sixteen books, the chief ones among them being the Krista Purana, a Konkani-Marathi discourse in verse of the history of salvation, written in the style of the Hindu Puranas; Doutrina Christam em Lingoa Bramana Canarim, a catechism in Konkani and Arte da lingoa Canarim, the first printed Konkani grammar. With the closure of the printing press at the college, the printing activity in Goa ceased, to reappear only in 1821, when the government of Goa imported a printing press from Bombay in order to publish the official weekly “Gazeta de Goa.” The corridors and walls of the Seminary are adorned with many valuable and rare frescos and paintings, many of which have suffered the ravages of time. Among these works of art, the paintings (copies) of the celebrated Goan artist Angelo da Fonseca, student of Rabindranath Tagore and pioneer in Indian Christian art, are worth mentioning.

Rachol has also produced historians, writers, grammarians, scientists, scholars, pastors, parliamentarians and university professors. Among the latter we can single out the saintly and very popular Ven. Fr. Agnelo Gustavo Adolfo de Souza, sfx, (Padr Agnel) who underwent his priestly formation and was ordained at the Rachol Seminary. He later joined the Society of St. Francis Xavier (Pilar Society), and spent the last 10 years of his life as Confessor and Spiritual Director of the seminarians at Rachol. Fr. Thomas Stephens (Konkani and Marathi writer), Francisco de Souza (author of Oriente Conquistado), Msgr. Rudolfo Sebastião Dalgado (Konkani writer and scholar, known as the God-father of the Konkani language), Fr. Antonio Francisco Souza (Science writer and thinker) are some of the well-known personalities associated with Rachol Seminary, either as staff or students.

Swami Vivekananda is said to have made several trips to the seminary, from Margao, where he had put up during his visit to Goa in 1892. He consulted the library at Rachol and discussed Christian theology and spirituality with the Professors of the seminary. This visit of Vivekananda to Rachol was in preparation for his famous address at the Parliament of World Religions in Chicago (11 to 27 September 1893), where Vivekananda represented India and Hinduism.IV Centenary Jubilee Celebrations The Santa Cecilia Choir in Concert (at Bom Jesus Basilica) at the closing of the IV Centenary Jubilee celebrations

The Santa Cecilia Choir in Concert (at Bom Jesus Basilica) at the closing of the IV Centenary Jubilee celebrationsOn 1 November 2010, the Archbishop-Patriarch of Goa and Daman, Most. Rev. Filipe Neri Ferrão opened the IV centenary Jubilee celebrations with a solemn high mass. A series of programs were organized all through the year. Some of the main events were: a spiritual Retreat; an Essay Competition for seminarians all over India; a 4-day long International Seminar convened by Dr. Victor Ferrão on Science and Religion focusing on "Catholicity in the World of Science"; Bible sessions for the laity; lenten Retreat for the neighbouring faithful; Seminars for Catechists of the surrounding parishes; a Konkani Seminar Amchem Daiz on the contribution of Rachol to Konkani literature; a Konkani play Panz, by the noted Konkani writer Pundalik Naik; an English operetta Be the Moon, libreto by Fr. Simião Fernandes and music by Fr. Romeo Monteiro, on the heroic life of the saintly Goan priest and Apostle of Sri Lanka Joseph Vaz (canonised by Pope Francis in 2015); and an all-Goa level Football Tournament for Altar Boys. A grand Concert of Sacred Music, featuring 150 musicians and singers, presented by the Santa Cecilia Choir of the Seminary with the involvement of ex-students and laity and conducted by Rev. Romeo Monteiro, Professor of Music at the Seminary, on 11 April 2011, brought the curtains down on the jubilee celebrations. The chorus of Te Deum laudamus, sung by those gathered in the Basilica of Bom Jesus, Old Goa, was executed as finale of thanksgiving to the Most Holy Trinity for the 400 years of service that Rachol has rendered to the Church in Goa and to humanity at large.

See also• Chorão Seminary

References1. Amaro Pinto Lobo, Memoria Historico-Eclesiastica da Arquidiocese de Goa em commemoracao do quadricentenario da sua ereccao Canonica, 1533-1933, Tip."A Voz de S.Francisco Xavier",Nova Goa, 1933, pg. 275

2. Carlos Merces de Melo, The Recruitment and formation of the Native Clergy in India, 16th to 19th century: An historico-canonical study - Agencia Geral do Ultramar, Lisboa, 1955, pg. 181ff.

3. "St. Paul's College, Rachol Seminary". Archdiocese of Goa and Daman. 2017. Archived from the original on September 15, 2013. Retrieved April 27, 2017.

4. Amaro Pinto Lobo, Memoria Historico-Eclesiastica da Arquidiocese de Goa em commemoracao do quadricentenario da sua ereccao Canonica, 1533-1933, Tip."A Voz de S.Francisco Xavier".

External links• Media related to Rachol Seminary at Wikimedia Commons